How Do Young Researchers Take the Steps toward Startup Activities?

A Case Study of a One-day Workshop for Entrepreneur Education

Miki Saijo

1

, Makiko Watanabe

1

, Takumi Ohashi

1

, Haruna Kusu

2

,

Hikaru Tsukagoshi

2

and Ryuta Takeda

2

1

Department of Transdiciplinary Science and Engineering, Tokyo Institute of Technology, Tokyo, Japan

2

Career Research Center, Leave a Nest Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan

Keywords: Business Startup, Creativity, KEYS Scale, Knowledge Creation, Business Plan Refinement Workshop.

Abstract: This is an exploratory study of how young researchers with specific scientific knowledge, through deep

conversations with mentors from industry in a Business Refinement Workshop (BRWS), are likely to change

their original business plans, and what the factors are that will stimulate them to take action for business

startup. It was found that the BRWS did lead to changes in business plan issues and solutions, but these

changes did not necessarily lead to specification of the business plans. It was also found that a positive

perception to the discrepancy of the mentors’ comments was a factor that could stimulate startup activity after

the workshop.

1 INTRODUCTION

On January 2, 2010, the Washington Post reported

that in the U.S. economy there was zero net job

creation in the first decade of the twenty-first century.

Even though the U.S. economy has grown steadily

over the past 70 years and has been a driving force in

the world market, in recent years the climate for job

creation has been changing. Ford (2015) notes that

companies like Google and Facebook, for example,

have succeeded in achieving massive market share

while hiring only a tiny number of people relative to

their size and influence. And also he claims that

"predicable" jobs, that is fundamentally routine jobs

and jobs requiring a degree of expertise, will be taken

over by machines. The result will be the playing out

of similar scenarios to those of Google and Facebook

in nearly all new industries created in the future.

According to a 2010 Kauffman Foundation report,

startups, or age zero firms, have been the main creator

of new jobs in the U.S. since the 1970s. The report

notes that "job creation at startups remain stable,

while net job losses at existing firms are highly

sensitive to the business cycle". Startups are

indispensable for net job acceleration, but they are not

so active in Japan.

The Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM)

provides one of the most comprehensive surveys on

entrepreneurship around the world. Its 2014 report

crystalizes the situations of more than 206,000

individuals in 73 economies. In this report, based on

the World Economic Forum Global Competitiveness

Index, Japan is classified as an Innovation-driven

Economy. The United States, many EU countries

(such as Germany and the United Kingdom), and

Singapore are in the same category. But the report

also indicates that Japanese society gives less social

value to startups compared to the other countries

listed above. Also, at this point in time, the Japanese

people in general seem to have fewer of the individual

attributes that lead to entrepreneurship activities. For

example, the percentage of Japanese people who

consider starting a new business a "desirable career

choice" is 31% while those of the other four countries

is over 50%. Since social value plays a pivotal role in

an individual’s action to become an entrepreneur

(Kwon and Arenius, 2010), this data strongly

indicates the vulnerable situation of the startup

business in Japanese culture.

Japan’s Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports,

Science and Technology (MEXT) is aware of the

importance of fostering nascent entrepreneurs and of

providing education for innovation, and there are two

MEXT programs dealing with this. The Program for

Leading Graduate Schools (Leading Program)

initiated in 2011 supports 62 graduate programs to

nurture next-generation leaders having broad

perspective and creativity. The program clearly aims

to produce quality graduate students with various

Saijo, M., Watanabe, M., Ohashi, T., Kusu, H., Tsukagoshi, H. and Takeda, R.

How Do Young Researchers Take the Steps toward Startup Activities? - A Case Study of a One-day Workshop for Entrepreneur Education.

DOI: 10.5220/0006066502150222

In Proceedings of the 8th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management (IC3K 2016) - Volume 3: KMIS, pages 215-222

ISBN: 978-989-758-203-5

Copyright

c

2016 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

215

career choices (in contrast to traditional academic-

centered careers), that include starting up a new

business. Additionally, in 2014, MEXT also started

the Enhancing Development of Global Entrepreneur

(EDGE) program which currently supports 13

programs specifically aimed at accelerating

innovation through entrepreneurial education on

startups and organizations. Still, though the

government is actively pushing for entrepreneur

education, the program curriculums still involve a lot

of trial and error. In summary, Japanese entrepreneur

education is still at the predawn stage.

The question is how to bridge higher education

with the encouragement of nascent entrepreneurs; or

more precisely, how to transform young researchers

with scientific expertise into nascent entrepreneurs

who can create new jobs through the diffusion of

innovation. This is not only a challenge for Japan but

also one for the global community.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 The Variables That Affect the

Decision to Start a Business

Clercq and Arenius (2006) statistically analysed data

collected for the 2002 Global Entrepreneurship

Monitor and concluded that knowledge-based factors

have a strong impact on the decision to engage in

business startup activities. According to their

regression analysis of the likelihood of being engaged

in business startup activity, "specific skills" and

"personally knowing an entrepreneur" significantly

affected the dependant variable in all their sample

subgroups–a control group, a Belgium group, and a

Finland group. As to education level, they found that

a secondary degree had a positive effect in the control

group, but a post-secondary degree did not affect the

dependant variable in any of the groups. This result

suggests that specific skills and exposure to

knowledgeable others are significant factors, while

higher education does not necessarily push people to

become nascent entrepreneurs. Highly elaborated

existing knowledge is supposed to be indispensable in

generating new ideas and engaging in business startup,

but the accumulation of existing knowledge does not

necessarily link to business startup activity. There is

a need to bridge existing knowledge and external

knowledge, and to transform an individual’s tacit

knowledge to shared knowledge. How can we bridge

these different kinds of knowledge?

Nonaka and Toyama (2003) state that "knowledge

creation is a synthesizing process through which an

organization interacts with individuals, transcending

emerging contradictions that the organization faces",

and "one can share the tacit knowledge of others

through shared experience". In order to transform

tacit knowledge to shared new knowledge,

socialization and efforts to transcend contradictions

are needed (Saijo et al, 2014). Saijo et al, (2014)

executed an action study in which a 4-wheel electric

power-assisted bicycle was lent to frail elderly people

and observed how physiotherapists created new

knowledge in assisting the frail elderly people to ride

the newly invented AT-device: a 4-wheel electric

power-assisted bicycle. In this research, having a new

device evaluated within the context of a care facility

served as an impetus to transform the tacit knowledge

of professional caregivers into explicit knowledge.

This required close collaboration among the device

maker, researchers, and caregivers, and the city hall

staff also played an important role as intermediaries

bringing together diverse professionals and the staff

of the care facilities.

This previous study points to the importance of

knowledge creation formed through collaboration or

interaction among people with different backgrounds

who work together to transcend difficulties. In

seeking to push highly educated people to start a

business, it can be helpful to find a way to encourage

knowledge creation among them.

If knowledge creation is a process by which

organizations interact with people to create new and

useful knowledge that will help them transcend

difficulties or achieve challenging goals, then it

seems reasonable to consider creativity to be the

product of knowledge creation.

2.2 Creativity and Innovation

Amabile et al, (1996) defined creativity as "the

production of novel and useful ideas by individuals or

teams of individuals". Creativity is not merely a result

of an individual’s characteristics but also the result of

the interaction between an individual and work

circumstances. Creativity is a key factor in starting a

new business, but it is still not clear how to encourage

or foster this creativity.

KEYS: Assessing the Climate for Creativity

(formerly, Work Environment Inventory) gives six

stimulant scales and two obstacle scales affecting

creativity (Amabile, et al, 1996). KEYS was

developed based on the human capital theory,

especially the interactionist concept (Woodman,

Sawyer, and Griffin, 1993). KEYS focuses on how

KMIS 2016 - 8th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

216

workers perceive the relationship between the work

environment and team creativity. Amabile et al,

(1996) compared highly creative projects and low

creative projects in a construct-validity study. For the

stimulant scales, KEYS gives Organizational

Encouragement, Supervisory Encouragement, Work

Group Supports, Freedom, Sufficient Resources, and

Challenging Work. The obstacle scales are Workload

Pressure and Organization Impediments. They

analysed the relation between work environment

perceptions and creativity by collecting data totally

12,525 with variety of functions and departments and

organizations. The results show that in the six scale

of challenging work, organizational encouragement,

work group supports, freedom, organizational

impediments, and supervisory encouragement, there

is strong discrimination between two levels of

creativity. The study concluded that high-creativity

projects were generally rated higher on the stimulant

KEYS scales and lower on the obstacle scales

(Amabile et al, 1996). It was also concluded that this

result was not affected by other project variables:

project length, size of project team, organization of

project team, etc.

The present paper deals with a one-day

entrepreneur workshop for Leading Program students

as an inter-organization project, and evaluates the

factors which positively affect a student’s motivation

to undertake business startup activities using the

KEYS scale framework. We applied the four positive

scales which were shown to be highly effective in

Amabile et al, 1996: challenging work, work group

supports, organizational encouragement and

supervisory encouragement.

3 CASE STUDY

METHODOLOGY

3.1 Background

One of the goals of the Leading Program, being

implemented at prestigious graduate schools in Japan,

is to nurture students so that they will acquire the

competence suitable for the following roles: (1)

leader, to solve social problems with their expertise,

and (2) project manager, to trigger innovation via

communication with various stakeholders. However,

it is difficult for students to experience leader and/or

manager roles in a collaborative project while they

are undertaking graduate study. As a result, students

lack experience in applying their academic

knowledge to solving problems in the real world. We

believe that this can only be remedied by actually

providing a setup where students and people from

industry co-create solutions.

We therefore arranged to have the Four Leading

Programs at the Tokyo Institute of Technology

organize a one-day Business-plan Refinement

Workshop (BRWS) in which students and people

from industry communicated with each other to co-

create a solution.

3.2 Research Questions

In introducing the BRWS we began with two

questions: (1) How can the BRWS be evaluated in

terms of the positive KEYS factors–organizational

encouragement, supervisory encouragement, work

group supports, and challenging work–that stimulate

the individual’s creativity within the team? By

describing the BRWS in terms of the KEYS factors,

we can evaluate the environment’s effectiveness in

stimulating the creativity of the participants by

exposing them to external knowledge for getting new

and useful ideas. (2) Which factors are effective in

stimulating highly educated young researchers to take

action on startup activities? By searching for these

factors, we seek to develop a methodology for

stimulating creative ideas for business startups.

The four categories of the first question were further

broken down into additional questions as follows:

Organizational Encouragement: What are the

distinguishing characteristics of the BRWS and the

ways in which MEXT, the organizers, and the

participating university encourage Leading Program

students to participate in this event, and what was

their level of satisfaction with the workshop?

Supervisory Encouragement: How do mentors and

students cooperate in drafting a creative business plan

in the BRWS setting, and how do researchers changed

their business plan in order to create new and useful

ideas?

Work group Supports: In the BRWS, how did young

researchers perceive their mentors’ suggestions for

refining their business plan?

Challenging Work: How do students link their

workshop and post-workshop action to their business

startup?

By evaluating the effectiveness of the one-day

BRWS, as an environment in which young

researchers refine their business plans through deep

communication with their mentors, we seek to

develop a methodology for stimulating creative ideas

for business startups.

How Do Young Researchers Take the Steps toward Startup Activities? - A Case Study of a One-day Workshop for Entrepreneur Education

217

3.3 Method

Participants in the BRWS were: 22 young researches

(10 masters and 12 PhD students in Leading

Programs at 7 universities) and 20 mentors from 5

major companies and 9 venture companies. The

Tokyo Institute of Technology, the first author’s

place of work, organized this event and Leave a Nest

Co., Ltd, the last author’s place of work, sponsored

and facilitated the workshop. Students submitted their

business plan proposals 1 month before the workshop,

and 10 teams were selected to participate in the

BRWS. The business plans were submitted to a panel

of judges just before the workshop, and then again

after they had been refined in the workshop. The

refining of the business plans was carried out in the

workshop by 10 inter-organizational teams

comprising the above mentioned students and

business persons.

Three months after the workshop, 10 people who

were involved in BRWS from the sponsor company

were asked to evaluate the originality and practicality

of the revised business plan PowerPoint presentations

that came out of the BRWS. Around the same time

we followed-up with interviews of the student

participants to see what kind of activity may have

been triggered by the workshop. One of our co-

authors interviewed 15 students by phone. One of the

interviews was disqualified because the student did

not answer all the questions, and the remaining 14

student interviews were analysed for the present study.

Permission was obtained from all 14 students and

from the organizing university to use the interview

data.

• Period: March 5, 2016 to July 5, 2016

BRWS: March 5, 2016

Post event evaluation: June 16 to July 9, 2016

Post event participant interviews: June 16 to July

7, 2016

• Targets: 1) Masters and PhD students in Leading

Programs (hereafter "young researchers") who

participated in both the BRWS and the post event

interviews; and

2) Business persons in the major companies and

venture companies who participated in the BRWS

as mentors (hereafter "mentors"); and

3) Employees from the sponsor company who

took on the roles of supporter and facilitator at the

BRWS and who were asked to compare the

original and revised versions of the business plans

(hereafter "evaluators").

• Methods: Rating pre- and post-BRWS business

plan PowerPoint presentations made by the young

researchers, and making quantitative and

qualitative analyses of the post-workshop

interviews of the students.

The objective of the present study is to seek the

factors stimulating young researchers to take action

on startup activities. By using KEYS, we can evaluate

the effectiveness of the environment in stimulating

creativity, i.e., knowledge creation, and get a grasp on

whether the participants are sufficiently exposed to

external knowledge to get new and useful ideas. We

therefore put the data acquired through the BRWS

and interviews into the KEYS scales framework to

derive indices for evaluating the effectiveness of the

environment.

3.3.1 Organizational Encouragement and

Supervisory Encouragement

Organizational encouragement is the encouragement

provided by an organization to its people.

Supervisory encouragement is related to the work

models, goals, and support provided by supervisors

(Amabile et al, 1996). In this article we describe how

we organized this event and how MEXT, the

organizing university and other member universities

encouraged young researchers to participate this

event.

Table 1: Students’ business plan topics and mentors’

industry sectors.

Group

Business plan topic and mentor industry

sectors

# of students

(post-event

interviewees)

A

Exhaust gas treatment & plant factories

Agriculture, Media service

2 (2)

B

Applying ICT in the operation of locally based

corporate childcare facilities

Education, IT

3 (1)

C

Enzyme treatment system for wastewater containing

oils and fats

Device manufacturer, Biotech service

2 (2)

D

Shotgun cloud working system for employing older

workers and enhancing specialized skills of younger

workers

Education (2 mentors from one company)

2 (0)

E

A Water-powered acetylene engine motor vehicle

Car industry (2 mentors from one company)

1 (1)

F

Revitalizing Odaka town - Fukushima after the triple

disaster

IT, Angel Investor

2 (1)

G

Reducing the waiting list for daycare and increasing the

number of daycare workers

IT (2 mentors from one company)

3 (2)

H

Development of a "sleep controller" and new business

model using IoT for better treatment of sleep disorders

Device manufacturer, Telecom

3 (3)

I

Small in-wheel motor and dissemination of a new sport:

CarryOtto

Device manufacturer (2 mentors from one company)

1 (1)

J

Ubiquitous healthcare service system based on the SPA

architecture model for smart hospital

Device manufacturer, Food

2 (1)

KMIS 2016 - 8th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

218

Information on this event was distributed by

MEXT to all of the 62 Leading Programs in Japan.

MEXT also advised each program to disseminate the

information to young researchers and to call for

proposals. The event was held in Tokyo, and travel

expenses were covered by each program. Though the

event included a poster session in addition to the

BRWS, this article does not discuss the poster session

since the authors’ focus is on elucidating the effect of

interaction between the young researches and their

mentors during the BRWS. The mentors from

industry were actively recruited by the sponsor. Table

1 summarizes the students’ business plans, and gives

the industry sector of the mentors for the first session.

Except for the E team, each team had two mentors in

each session.

The mentor’s business category is given under the

title of each proposal. It is italicized if the company is

a venture company. Here venture company is defined

as one within 10 years of corporate registration.

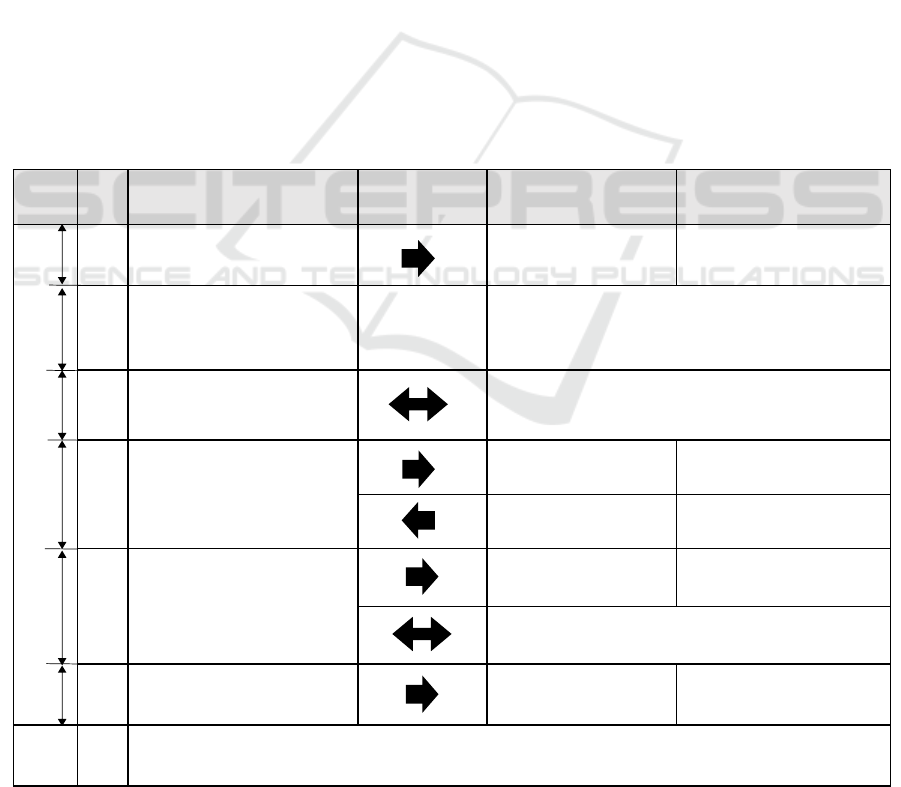

Figure 1 shows the step by step flow of the BRWS.

The time frame for each step is shown in the left

column. The name of the step, activity, and the

student and mentor’s activity are summarized. The

middle column shows the direction of communication.

If the students mainly explained things to their

mentors, then the arrow points to the right. If the

mentors were mainly explaining and/or giving

feedback to the students, the arrow points to the left.

If there was free exchange of opinions, then a double

arrow is used. Each step is explained as follows. Step

0: Before the workshop starts, the students present

their ideas. Step 1: the BRWS starts with brief

guidance from the workshop facilitator. Step 2:

Students and mentors fill in three different

worksheets together. Step 3: Mentors are changed,

and the students explain the ideas discussed in Step 2,

with the new mentors giving feedback. Step 4: The

original mentors return and the 3 worksheets filled

out in Step 2 are revised. At this time, the teams of

students and mentors are advised to resolve the

questions that arose in Step 2 and 3. Step 5:

Presentations are made of the polished ideas created

in the workshop. During the workshop, mentors made

suggestions for commercialization speaking from

totally different perspectives. Deep communication

lead to further reworking of the proposed plans.

As an index for organizational encouragement,

the degree of participant satisfaction was investigated.

Figure 1: Flow of the BRWS.

Time

Frame

(min)

Step Name of the activity

Direction of

communication

Activity of students

(S)

Activity of mentors

(M)

0

Original presentation

• 4 min for presentation,

• No Q&A from judges

• Presentation • Listening to each presentation

1

Workshop Guidance

• To explain the time frame of

the workshop

• To explain how to use 3

worksheets

N/A • Listening to facilitators’ guide

2

Workshop Round 1

• Fill in Worksheet 1

• Fill in Worksheet 2

• Fill in Worksheet 3

• Exchange information

• Co-create business scheme

3

Workshop Round 2

• Mentor exchange and

discussion

• To explain the idea

generated in Round1

• Listening to the idea

presented by the team

assigned newly

• To discuss about the

issue brought up by new

mentors

• Asking questions to students’

plan

4

Workshop Round 3

• Mentor exchange (back to

originally assigned mentors)

and iterate Worksheet 1~3 to

polish the business plan

• To make final presentation

slides

• To explain the

discussion in Round 2

• Trying to understand the

point of which other

mentors questioned

• Exchange information

• Co-create business scheme

5

Final presentation

• 5 min for presentation

• 5 min Q&A from judges

Presentation of the polished

plan

Listening to each presentation

6

Questionnaire Survey

• Degree of satisfaction (4-point scale)

• Free description on good points of this workshop

45100 80

30 90

20

0

20

110

140

220

How Do Young Researchers Take the Steps toward Startup Activities? - A Case Study of a One-day Workshop for Entrepreneur Education

219

Also, as an index for supervisory encouragement,

the students were questioned about the degree of

disparity they felt in the mentors’ comments

3.3.2 Work Group Supports and

Challenging Work

The variables that appeared to make the largest

contribution to enhancing the creativity of the teams

were work group supports and challenging work. An

individual assigned a difficult objective is the most

creative when supported by the team (Amabile, T.M

et al., 1996). The taskes assigned to the young

researchers in the BRWS were quite difficult. As

explained above, the students were repeatedly

required to polish their proposals and twice were

subjected to differing comments from two different

sets of mentors. After this they worked again with the

first set of mentors to revise their proposals and

prepare a PowerPoint presentation to be made before

a panel of judges. This process resulted in disparity

between the students’ original proposals and the

polished versions, which can be seen in a comparison

of the proposals made before and at the end of the

BRWS. In this study, 10 evaluators were asked to

evaluate the portions of the proposals that had

changed.

The objective of the BRWS was to transform the

young researchers’ existing knowledge into new and

effective ideas for business startups offering solutions

to social problems. The evaluations of the changes in

the PowerPoint presentations therefore focused on the

changes that may or may not have taken place in the

proposals’ issues and specific milestones for

achieving those objectives, and these were used as the

indices for judging the degree of novelty and

innovation.

3.3.3 Factors Stimulating Young

Researchers to Take Action Leading to

Startup Activities

In the post-event interviews, 14 young researchers

were asked the following questions.

1) Was there anything in the mentors’ comments and

advice that was incompatible with your proposal

or ideas?

2) How would you rank the sense of disparity you felt

on a scale of 1 to 5?

3) Why did you feel they were incompatible with your

ideas?

4) Did you take any action to implement your plan

after the event ended?

5) How would you rank that action on a scale of 1 to

5?

Each interview was conducted by telephone by

one of the co-authors. Tapes of the telephone

interviews were then transcribed and the data for this

study was generated from the interview transcripts.

The emergence of novel and useful ideas required that

the young researchers find disparity in the mentors’

comments regarding their business plans. Whether

their perception of this disparity was positive or

negative was also a factor to be taken into

consideration. For the purposes of this article, the 14

interviewees’ responses to the question of disparity

were divided into 67 sentences and two co-authors

other than the interviewing co-author used these

sentences to judge whether the response was positive,

negative, or neutral. This evaluation was based on the

extent to which the sentences indicated a new

awareness on the part of the young researcher.

Responses were judged to be neutral when they

indicated that the young researchers did not feel the

comments to have influenced their own actions.

Below is an example of this coding results, the coding

concordance rate was 95.5%.

Positive: The mentor’s question, "Can’t the

treated discharge water be used again?" was

unexpected and new idea.

Negative: I did not find it helpful.

Neutral: The comments of the mentors differed

according to whether they represented a major

company or a venture business.

Correlation and regression analysis were carried

out using the following variables: The response

variables as to whether or not action toward business

startup was taken after the workshop; the evaluation

variables of the PowerPoint presentations (degree to

which changes were introduced for new issues; new

solutions; specificity of proposed milestones); and the

explanatory variables of the interviews (degree of

perception of disparity, ways of perception of dispa-

rity: positive-neutral-negative). For the statistical

analyses, Esumi multivariate data analysis Excel

software (version 6.0) was used.

4 RESULT

4.1 KEYS Positive Factor Evaluation

for BRWS

4.1.1 Organizational Encouragement and

Supervisory Encouragement

The young researchers participating in the workshop

received financial support from MEXT, and their

KMIS 2016 - 8th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

220

universities also treated the workshop as a part of

their Leading Program curriculum. A high 80%

responded that they were satisfied with the BRWS.

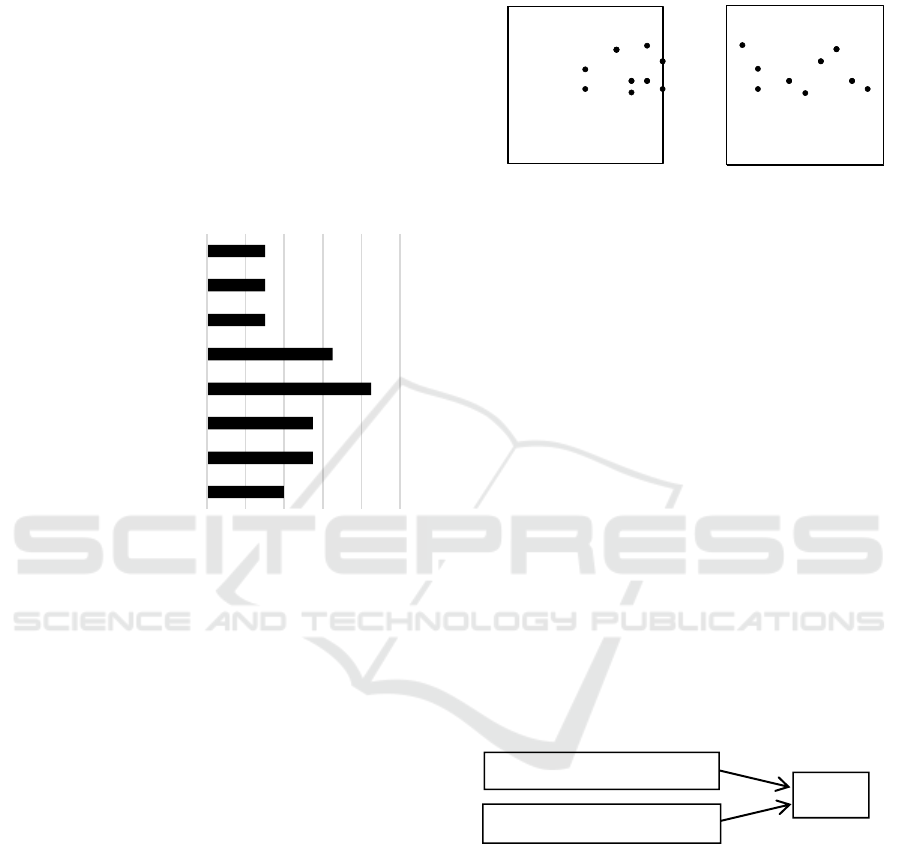

Figure 2 shows what the students felt were the good

points of the workshop. There may be some objection

to using degree of satisfaction as a measurement of

"organizational encouragement", but the objective of

this study was not to measure the perception of

encouragement but to seek out the results of the

encouragement, and the degree of satisfaction in the

workshop was therefore used as a measure. Figure 2

shows the breakdown of the responses to the multiple

choice question on satisfaction.

Figure 2: Good points of the workshop.

Most of the students (85%) selected "Discussion

with mentors" as one of the good points. The second-

largest number of students (65%) selected

"Opportunity to get ideas for business". On the other

hand, fewer students selected "Autonomous business

concepts making (40%)" and "Reviewing ideas and

making presentations twice (30%)".

4.1.2 Work Group Supports and

Challenging Work

We calculated the correlation factors between the

three variables (reconstructed issues in business plans,

reconstructed solutions, and proposed milestones) of

the PowerPoint presentation evaluations between the

specificity of the milestones and the ratio of

reconstructed (a) issues/(b) solutions.

Variables in each case were derived as follows:

for the ratio of issues and solution reconstruction, the

ratio of evaluators who judged the issues or solutions

to be reconstructed; and for the specificity of the

milestones, the mean value of 4-scale evaluation of

the milestone specificity. The results showed in

Figure 4. From these results, we concluded that there

is no correlation between increases in the ratio of

business plan reconstruction and improvements in the

specificity of the business plans.

Figure 3: Relation between specificity of the milestones and

ratio of reconstructed (a) issues/(b) solutions.

4.2 Factors Stimulating Young

Researchers to Take Action

Leading to Startup Activities

Multiple regression analysis was carried out using the

explanatory variables of PowerPoint presentation and

the interviews. Stepwise regression analysis was

applied, and it led us to have two significant

explanatory variables for the response variable of

presence/absence of action (Y). They were the degree

of perception of disparity (X

1

) and positive perception

to this disparity (X

2

).

Y = -1.37 + 0.28X

1

+ 1.15X

2

(1)

Adjusted R-square was 0.90, and since the P

values were all statistically significant, it was

determined that variables with sufficient explanatory

power had been selected. Figure 4 shows structure

determining whether or not action is taken.

Figure 4: Structure determining whether or not action is

taken.

5 CONCLUSION AND FURTHER

RESEARCH

This was an exploratory study of the factors that will

stimulate young researchers with specific scientific

knowledge, when engaged in deep conversations with

mentors from industry in a Business Refinement

Workshop (BRWS), to take action for a business

startup. In describing the BRWS environment of

0 20406080100

Autonomous business

concepts making

Objective evlaluation of ideas

Making presentations to

business people

Discussions with mentors

Opportunity to get ideas for

business

Reviewing ideas and making

presentations twice

Clarifying of ideas

Integrating of ideas

Percentage that apply (%)

1

2

3

4

5

0 20406080100

Specificity of the milestones

Ratio of reconstructed issues

r=-0.022 P=0.942

1

2

3

4

5

0 20406080100

Specificity of the milestones

Ratio of reconstructed solutions

r=-0.041 P=0.890

(a) (b)

Action

Perception of disparity

Positive way of perception

+

+

How Do Young Researchers Take the Steps toward Startup Activities? - A Case Study of a One-day Workshop for Entrepreneur Education

221

knowledge creation in terms of the KEYS factors, it

was found that this environment did lead to the

reconstruction of business plan issues and solutions,

but not necessarily to specific business plan

milestones. Although there was no correlation

between the milestones’ specificities and the

reconstruction of business plan issues/solutions, we

did find that the perception of disparity in the mentors’

comments could stimulate startup activity after the

workshop. This finding expands on prior work by

Clercq and Arenius (2006) who found that exposure

to external knowledge may enhance the likelihood to

engage in business startup activity. In other words,

not merely exposure to external knowledge, but also

perception of disparity, are key factors that push the

participants towards starting a business. Moreover,

we also found that positive perceptions of the

disparity could be another factor stimulating such

activity.

This study can be deemed to have the following

limitations.

1) The KEYS scales were used to evaluate the

effectiveness of the workshop, but no

introspective study of the KEYS scales has been

made and there is therefore no way to judge if the

indices used in this study are consistent with the

KEYS scales.

2) There is no record of the actual interaction that

took place in the workshop and therefore no way

of knowing what kinds of comments had positive

disparity.

3) There was no evaluation of the milestone

specificities of the original business plans, and

therefore no way of knowing how they changed

through the BRWS.

Despite these limitations, it was still possible to

get some insight into the methodology of a workshop

directed at stimulating highly educated human

resources towards starting up their own businesses.

Hereafter, we would like to gain further insight by

introducing methods that will overcome the above

limitations, and open up pathways to tying

specialized knowledge to business startups and

education that will accelerate innovation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to express our deepest appreciation to

the participants and organizing staff of BRWS and

MEXT for their help with the case study presented in

this paper.

REFERENCES

Amabile, T. M., Conti, R., Coon, H., Lazenby, J., Herron,

M., 1996. Assessing the work environment for

creativity. Academy of Management Journal, 39 (5),

1154-1184.

Clercq, D. D., Arenius, P., 2006. The role of knowledge

in business start-up activity. International Small

Business Journal, 24(4), 339-358.

Ford, M., 2015. The Rise of the Robots: Technology and the

Threat of Mass Unemployment. Kindle edition,

Oneworld Publications, London, UK.

Irwin, N., 2010. Aughts were a lost decade for U.S.

economy, workers. The Washington Post, 2 Jan,

available at: http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-

dyn/content/article/2010/01/01/AR2010010101196.ht

ml (accessed 18 July 2016).

Kane, T., 2010. The Importance of Startups in Job Creation

and Job Destruction. Kauffman Foundation Research

Series: Firm Formation and Economic Growth.

Kwon, S-W., Arenius, P., 2010. Nations of entrepreneurs:

A social capital perspective. Journal of Business

Venturing, 25(3), 315-330.

Nonaka, I., Toyama, R., 2003. The knowledge-creating

theory revisited: knowledge creation as a synthesizing

process. Knowledge Management Research and

Practice, 1(1), 2-10.

Saijo, M., Watanabe, M., Aoshima, S., Oda, N.,

Matsumoto, S., Kawamoto, S., 2014. Knowledge

creation in technology evaluation of 4-wheel electric

power assisted bicycle for frail elderly persons - a case

study of a salutogenic device in healthcare facilities in

Japan. Proceedings of the 6th International Conference

on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing,

Rome, 87-100.

Singer S., Amorós J. E., Arreola D. M., 2015. Global

Entrepreneurship Monitor 2014 Global Report, Global

Entrepreneurship Research Association.

Woodman, R. W., Sawyer, J. E., Griffin, R. W., 1993.

Toward a theory of organizational creativity. Academy

of Management Review, 18(2), 293-321.

KMIS 2016 - 8th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

222