New EEG Measure of the Alertness Analyzed by Emotiv EPOC

in a Real Working Environment

Dariusz Sawicki

1

, Agnieszka Wolska

2

, Przemysław Rosłon

1

and Szymon Ordysiński

2

1

Warsaw University of Technology, Institute of Theory of Electrical Engineering,

Measurements and Information Systems, Warsaw, Poland

2

Central Institute for Labour Protection - National Research Institute (CIOP-PIB), Warsaw, Poland

Keywords: EEG, Alertness Level, Emotiv EPOC.

Abstract: Alertness level evaluation has obvious implications for safety–critical occupations such as operators in

control rooms or drivers. It has already been stated that alertness can be assessed objectively by EEG.

However, the high costs of standard medical equipment for EEG measurement, their complex and time-

consuming operation, and the need to use conductive gel on the scalp make this method impossible for

general use or at workstations. The aim of the study was to analyze the possibility of alertness level

assessment based on EEG measurements using the Emotiv EPOC headset, which is relatively cheap,

wireless, comfortable for wearing and does not need the use the of conductive gel, but allows the capture of

only 14 channels of EEG. The experiments were carried out in laboratory conditions using three different

light spectra for 40 minutes exposure on office workstation during the afternoon drop in alertness. 50

participants took part in each light scene (white, red, blue). The EEG measurements were performed before

exposure and just after exposure to a particular light scene. A new measure of alertness, based on analysis of

EEG signals, has been introduced. The results showed that this new measure based on low-cost Emotiv

EPOC EEG measurements is reliable and confirms the results of previous studies.

1 INTRODUCTION

1.1 Motivation

Studies on alertness levels have been conducted for

many years. This study is important for ensuring

safety at work, and also due to the possibility of

increasing efficiency. The methodology for these

tests is usually based on an analysis of the contents

of melatonin in the blood, urine or saliva. Such a

study is the simplest test of alertness in laboratory

conditions, but difficult or impossible in real

conditions – in the workplace, for example for

drivers. Therefore, the need for another method

which enables the effective recognition of the level

of alertness. For several years, research on the

melatonin level in blood has been combined with the

analysis of EEG (Rahman et al., 2014, Sahin and

Figueiro, 2013, Sahin et al., 2014, Górnicka, 2008).

At the same time, systems based only on the analysis

of EEG signals have been developed. Research

conducted among drivers are a good example of this

(Ji et al., 2011, Li et al., 2010).

Participant comfort during the performance of

tests is a basic prerequisite for the practical

application of EEG in the diagnosis of alertness

level. This is especially so if the tests are carried out

on a large group of participants. The traditional

medical equipment for EEG recording, in which it is

necessary to use a conductive gel, does not meet this

condition. Tests organized in this way disqualify the

use of EEG signals in the identification of alertness

in the workplace. Therefore, increasingly often we

notice attempts to use a simpler device, equipped

with saline electrodes (not gelled) – a low-cost

(consumer edition) device. The above conditions are

clearly met by the Emotiv EPOC (Emotiv Systems

Inc.) device, which in recent years has also been

used to analyze EEG signals (Stytsenko et al., 2011,

Pham and Tran, 2012, Zhan, 2013, Badcock et al.,

2013, Fakhruzzaman et al., 2015). Comparisons

between signal analysis based on Emotiv EPOC and

medical EEG devices have been performed

(Duvinage et al., 2012). As a result of these

comparisons, it has been concluded that Emotiv

should only be chosen for non-medical, non-critical

applications. On the other hand, Ramirez and

Vamvakousis (2012) tried to detect emotion from

Sawicki, D., Wolska, A., Rosłon, P. and Ordysi

´

nski, S.

New EEG Measure of the Alertness Analyzed by Emotiv EPOC in a Real Working Environment.

DOI: 10.5220/0006041200350042

In Proceedings of the 4th International Congress on Neurotechnology, Electronics and Informatics (NEUROTECHNIX 2016), pages 35-42

ISBN: 978-989-758-204-2

Copyright

c

2016 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

35

the EEG signals obtained using an Emotiv device.

Their conclusion was that indeed Emotiv allows the

registration of signals only from selected points

(from 10–20 system), but such registered signals are

sufficient for data analysis. Similar conclusions can

be found in one independent report (Ekanayake,

2010, updated in 2015). Badcock et al. (2013)

showed high similarity of signals registered by

traditional a medical EEG system and an Emotiv

EPOC.

Therefore, it is worth conducting a study where

the aim is to enable the recording of EEG in the

most friendly way for employees, while at the same

time in a way that enables the identification of the

level of alertness. Emotiv EPOC is a good example

of a low-cost consumer electronic device with

proven correct registration of signals, although we

must be aware that it has limited capabilities and

requires careful interpretation of the results.

1.2 EEG Signals as a Measure of the

Alertness Level

Studies show that for most people during normal

readiness state (and with eyes open) Theta waves

(4.5-8 Hz) and Alpha waves (8–12 Hz) practically

do not exist (Sahin and Figueiro, 2013, Baek and

Min, 2015, Klimesch, 2012, Okamoto, 2014). If they

occur, their amplitudes are minimal. It is assumed,

therefore, that if during the registration process (in a

state of readiness, work etc. with open eyes) there

are Theta and Alpha waves with greater amplitude,

this represents an increase in drowsiness and fatigue,

and thus a decrease in alertness (Lal 2001).

With eyes open, and with an decrease in

alertness, the amplitude of the waves of lower

frequency (and thus Theta and Alpha) increases.

While with closed eyes, and in a state of drowsiness,

Alpha wave activity begins to decline, and the

amplitude of waves Theta increases. Therefore, in

studies usually two types of waves are analyzed –

Alpha and Theta. Sometimes additional bandwidth

Low Beta (Beta 1) (12–18Hz) is taken into account.

This band is associated with commitment and mental

activity. It is combined with cognitive alertness and

states immediately before performing tasks requiring

alertness (Gola et al., 2013). However, a direct

correlation with the level of alertness has not yet

been showed.

The simplest and simultaneously most effective

way to stimulate alertness is to use light of a

particular color. The discovery of new receptors of

light (ipRGC - Intrinsically Photosensitive Retinal

Ganglion Cell) begun many studies on lighting,

which is biologically effective (Brainard, 2001,

Sahin and Figueiro, 2013, Sahin et al., 2014,

Thapan, 2001, Viola 2008). Studies have shown that

light with a wavelength range between 425 and

560 nm is effective in inhibiting melatonin secretion.

The maximum effectiveness of this process occurs

for blue light in the wavelength range from 460 to

480 nm, depending on the obtained results of the

tests and their interpretation (Brainard et al., 2001,

Thapan et al., 2001, Aube et al., 2013). Despite

minor differences in interpretation, the authors of

these studies are in full agreement about the effect of

blue light with short wavelengths on the

physiological process of secretion of the hormone

melatonin – the process responsible for the states of

modulation between sleep and wakefulness during

the day. The use of light blue (or white with a high

proportion of blue light) raises the level of alertness

and thus helps to achieve a higher level of

psychophysical efficiency at work (Rahman et al.,

2014, Sahin and Figueiro, 2013, Sahin et al., 2014,

Viola 2008).

1.3 The Aim of the Study

The aim of the study was to analyze the possibility

of identifying the level of alertness in the

registration of the EEG signal in real working

conditions. The tests were planned for a large group

of 50 participants. Due to the need for adequate

comfort of such a large group of participants, we

used EEG equipment which does not require the use

of a conductive gel and has wireless connection to a

computer (i.e. there was no wiring that could make

movements difficult).

The equipment (Emotiv EPOC) is also a non-

medical, consumer, low-cost device. In this context,

these studies might also answer the question about

the possibility of using such low-cost equipment in

this research. As a key factor that affects the

increase in alertness, lighting with a significant blue

component was applied. The white-color lighting

used in workrooms was used as a reference

condition ("placebo"), which should not elicit

alertness. In addition, we used red-color lighting as a

factor that influences the level of alertness but on a

different principle than that of blue.

2 METHODOLOGY

2.1 Participants

In the study, a group of 50 participants took part,

NEUROTECHNIX 2016 - 4th International Congress on Neurotechnology, Electronics and Informatics

36

mean age 47.84 ±16.51 years, range 22–67. In a

natural way, there was a division into two

subgroups: older (mean age 66.66 ± 3.54 years,

range 56–67) and younger (mean age 27.83 ± 3.59

years, range 22–32). Participants included 22

healthy male and 28 female volunteers. All

participants met the following criteria: no report of

any physical or mental health problems, no color

blindness, office workers or students with

experience of computer work, and no use of any

medication. The experimental protocol was

reviewed and approved by the Ethical and Bioethical

Committee of Cardinal Stefan Wyszynski University

in Warsaw. Informed written consent was obtained

from each study participant. Participants were paid

for their participation.

Every participant completed a Horne-Ostberg

Morningness-Eveningness Questionnaire (MEQ)

(Horne and Ostberg, 1976) before the study. The

mean of reported chronotype was 2.6 ± 1.06. In the

older subgroup, this was 2.2 ± 0.92, and in the

younger subgroup 3.2 ± 0.95. Participants kept a

sleep/wake diary during all weeks of the experiment,

starting one week before starting the study. These

diaries documented bedtimes, rising times and level

of sleepiness / alertness on an hourly basis.

2.2 Lighting Conditions

The assumption of the study was to show that

lighting in office working conditions of specific light

spectra can be used to increase alertness in the

afternoon, close to the post lunch hours. Some

literature (Figueiro and Rea, 2010, Hanifin et al.

2006, Sahin and Figueiro, 2013, Sahin et al., 2014)

has stated that exposure to blue and red light during

the afternoon elicits alerting effects in humans.

These studies used direct exposure to blue or red

light with fixed head position. The aim of our study

was to model lighting conditions which would be

applied at office workstations to elicit alertness.

Lighting of a special spectrum switched on for an

exposure time of about 40 minutes should allow the

performance of visual tasks with visual comfort,

adequate color recognition of the environment and

appropriate illuminance. So, the red or blue lights

were added to white light as a significant

component, which would influence the alertness

(Wolska and Sawicki, 2015). The three experimental

lighting conditions participants were exposed to

were:

Reference conditions – general lighting –

fluorescent white light (Tc = 4000 K,

Ra = 80), termed “white” lighting scene;

Blue enriched white lighting conditions –

general lighting + localized lighting: white

LEDs (4000 K) and blue LEDs

(λ

max

= 470 nm), termed “blue” lighting scene;

Red enriched white lighting conditions –

general lighting + localized lighting: white

LEDs (4000 K) and red LEDs

(λ

max

= 630 nm), termed “red” lighting scene.

The localized lighting was placed over the

participant's head to avoid direct sight of light

sources and glare during the experimental session.

Discomfort glare from general lighting was limited

to UGR < 16, which fulfilled the requirements of

lighting standard EN 12464-1 (EN 12464-1, 2011).

During the exposure, participants were sitting at the

computer workstation and performed visual tasks

while looking at the screen. Eye height was fixed to

about 1.20 cm above the floor. The illuminance at

the cornea was: 286 lx under “white” conditions,

714 lx under “blue” conditions and 842 lx under

“red” conditions.

2.3 Emotiv EPOC

Emotiv EPOC allows the recording of EEG signals

in accordance with the 10–20 system, but with a

limited number of electrodes. In the Emotiv system,

only 14 active electrodes are available, together with

two reference electrodes (P3 and P4). The electrodes

are arranged around the head of the participant,

within the structures of the following areas: frontal

and front-parietal: AF3, AF4, F3, F4, F7, F8, FC5,

FC6; temporal: T7, T8; and the occipital and

occipital-parietal: O1, O2, P7, P8. The device has an

internal sampling rate of 2048 Hz and after cleaning

artifacts, it is resampled to 128 Hz. Finally, EEG

signals are transferred wireless to a computer, where

they are stored in a file using edf format. Proper

impedance of electrodes is formed by the use of

physiological saline. The scheme of electrode

arrangement in the Emotiv headset is presented in

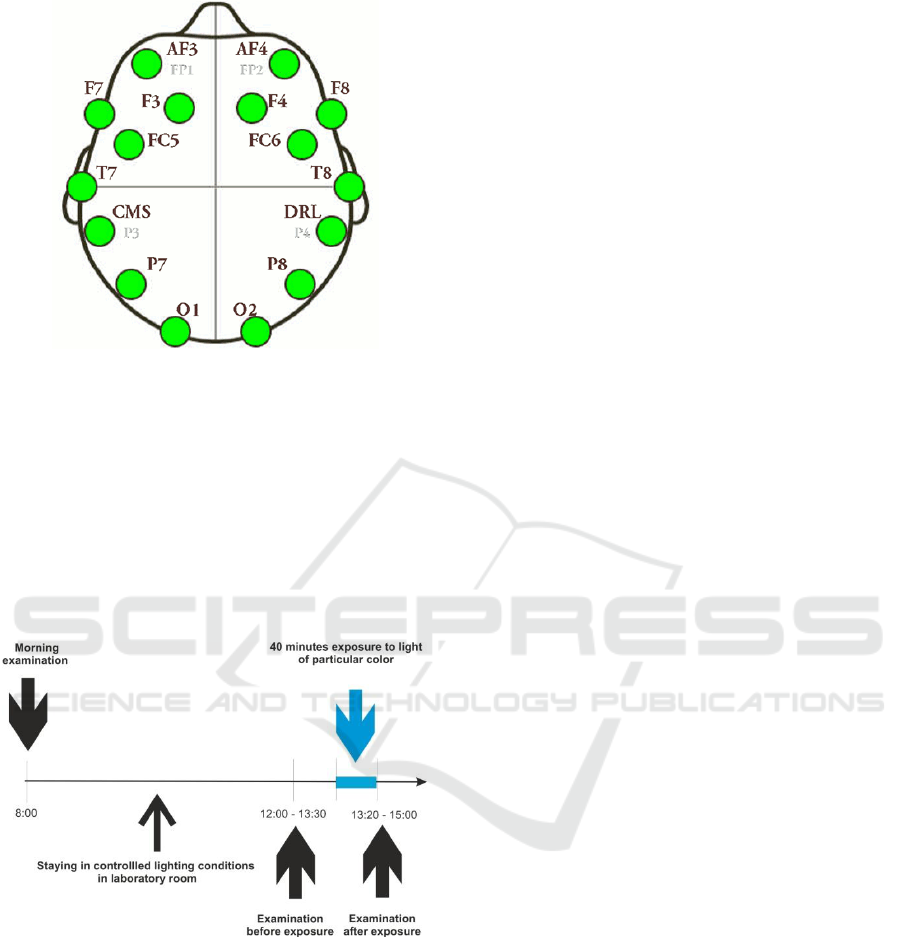

Figure 1.

The Emotiv system has a known disadvantage -

the lack of electrodes in the center of the skull (Pz,

Cz, Fz), and therefore, this system has limited

applicability in research. In our experiments,

missing signals were replaced by signals from

electrodes O1, O2, T7, T8, FC5, FC6. The

manufacturer of Emotive states that the signal

picked up by these electrodes would be good enough

to perform experiments with EEG registration.

New EEG Measure of the Alertness Analyzed by Emotiv EPOC in a Real Working Environment

37

Figure 1: Placement of electrodes on the headset in the

Emotiv EPOC system. Picture from (Emotiv Systems

Inc.).

2.4 Procedure of the Experiments

Participants were informed about the experiment and

trained in the performance of visual tasks a few days

before experiments. Participants were instructed to

be well rested before the experiments. Participants

were asked to refrain from alcohol and caffeine

intake during the experimental sessions.

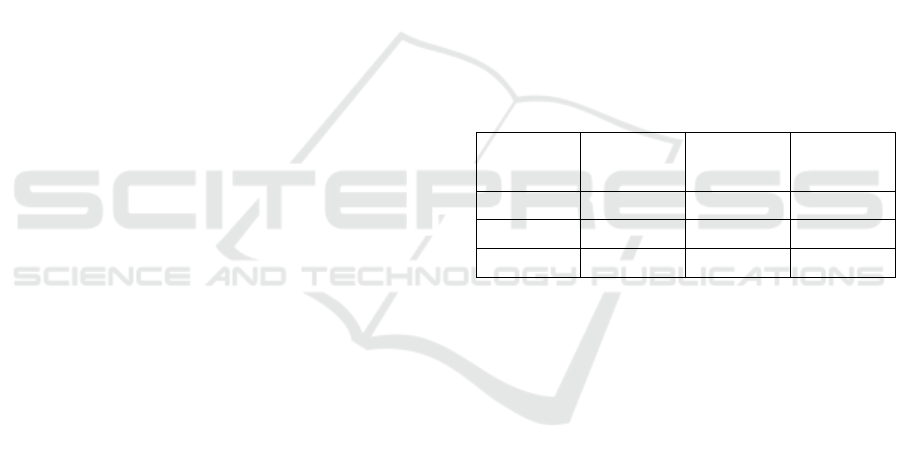

Figure 2: The course of the experiment, with time

dependencies, for one participant.

Participants experienced three experimental

sessions, separated by one week. On the

experimental days, participants arrived at the CIOP-

PIB laboratory at 8–8:30 AM and stayed in

controlled artificial lighting conditions under scene

“white”. They stayed until the afternoon drop in

their alertness (according to their sleepiness /

alertness assessment in personal diaries). Thereafter,

the first EEG measurements were carried out

(session “before exposition”). Then, one of three

lighting scenes, “white”, “red” or “blue”, was

modeled and participants performed visual tasks

typical for office work during 40 minutes of

exposure to particular light. At the end of the task,

the additional component (“red” or “blue”) of

lighting was switched off. Then, the second EEG

measurements were carried out (session “after

exposure”). The course of the experiment, with time

dependencies, for one participant is presented in

Figure 2.

All statistical analyses were carried out using

SPSS program version 18.

3 EEG ANALYSIS

3.1 Signal Acquisition

Signal acquisition took place using TestBench

software (from Emotiv System Inc.). We used a high

pass filter set at 0.2 Hz. To register markers that

signal the emergence of a stimulus on the screen, we

developed a communication between TestBench and

our original application CatchMe using the COM

port. After registration, we visually analyzed the

signal and we discarded fragments of the signal,

which cannot be solved in a different way. We used

EEGLab in this task. The next step was to filter the

signals in the frequency range 0.2 Hz – 40 Hz.

Initially prepared signal was analyzed by FFT

(Fast Fourier Transform) with 2 s Hamming window

and 1 s overlapping.

The next step was the visual analysis of the

collected data. We rejected cases where artifacts of

unknown origin occurred. We also rejected

incomplete registrations and those that did not

achieve the correct FFT analysis for all conducted

experiments. Finally, from the 50 sets of signals

(from 50 participants) we selected 46 for further

analysis.

Because of the lack of electrodes in the center of

the skull (Pz, Cz, Fz) in the Emotiv system, we have

to analyze signals from neighboring electrodes (O1,

O2, T7, T8, FC5, FC6). Preliminary trials before the

studies showed that the signals in such a situation

are of slightly lower quality but allow the

performance of analysis. Apart from artifacts, signal

registration in the Emotiv system often causes

problems of levels (signal levels at the various

electrodes may vary). In order to choose proper

electrodes, we analyzed the collected set of signals

and we selected electrodes from which we had better

quality of signals. Finally, we analyzed signals from

O1, T7 and FC5.

NEUROTECHNIX 2016 - 4th International Congress on Neurotechnology, Electronics and Informatics

38

For all participants the following bands were

selected:

Alpha 8–12 Hz from O1;

Beta from FC5;

o LowBeta 12–16 Hz;

o Beta 16–31 Hz;

o HighBeta 16–24 Hz;

Theta 4–8 Hz from T7;

AlphaTheta 5–9 Hz from T7;

DeltaTheta 0.3–3 Hz from FC5;

DeltaTheta 2.5–5.5 Hz from T7;

Total Power 6–40 Hz as average of all 14

electrodes.

In our experiment, we registered the above set of

signals for all participants. However, in the analysis

of the alertness we only used the frequency band of

4–12 Hz, because such a range is most commonly

documented in the literature (Sahin and Figueiro,

2013, Chang, 2013).

3.2 Analysis in Alpha Frequency Band

In the literature, we can find two general methods

for investigating symptoms of alertness in the EEG

signals. The first is where authors initially use

special mathematical algorithms for proper feature

extraction, for example principal component

analysis (PCA) in (Giusti, 2009). The second is

where the analysis is performed directly on the

signals (Sahin et al., 2014). The correlation between

level of alertness and level of proper bands of EEG

signals has been showed, so in our study we

analyzed directly registered EEG signals.

The most commonly used bands for

identification of alertness are: Alpha (8–12 Hz) or

AlphaTheta (5–9Hz) (Sahin and Figueiro, 2013,

Baek and Min, 2015; Klimesch, 2012, Okamoto,

2014). Therefore, initially we decided to analyze the

band Alpha. We analyzed the levels of Alpha before

being in a certain light scene and then afterwards. It

is reported in publications that an increase in

alertness should be associated with a decrease in the

level of Alpha (Lal, 2001).

Due to the high dispersion of data, which was the

result of a high level of precision, we decided to

transform the variables in order to reduce the

dispersion of the results. For this purpose, we carried

out the categorization of the dependent variables,

identified from the standard deviation values (+/- 1

to 3 standard deviations). Variables recorded in this

way show a decrease or increase in the measurement

of EEG both before and after exposure. This is a

change for the corresponding scaled value (1 to 8);

however, it does not show what value has changed

the EEG in each variable. From the description of

variables and recent statistics, it is known that the

exposure for each color has a different effect on the

value of the EEG. This resulted in different EEG

values, but the processed data did not take into

account this difference. For this reason, to each

identified group we assigned the average value of

the group. Such recordings were conducted

separately for each lighting scene (color).

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test showed that the

tested variables are not distributed normally. Not in

groups, not without grouping. Levene's test

confirmed the homogeneity of variance.

Analysis using the Student's t-test for

independent samples showed no statistically

significant difference in the decrease in EEG (before

and after exposure) among people from younger

subgroup compared to the results of measurements

for the older subgroup for all kinds of light

(Table 1).

Table 1: Results of the first analysis for Alpha band

between two subgroups of participants under different

lighting scenes. Equal mean t test.

Lighting

scene

t

df

significance

(two-sided)

White

1.159

45

0.252

Red

1.522

45

0.135

Blue

1.872

45

0.068

Because the analyzed variables did not meet the

requirements, we decided to confirm the test results

using the non-parametric equivalent. The Mann-

Whitney U Rank test unfortunately confirmed that

among the analyzed variables there are no

statistically significant differences.

However, it is worth paying attention to the

values of significance. For the “blue” lighting scene

we obtained a result that is close to the possibilities

of the hypothesis confirmation (significance = 0.068

– in comparison to the expected 0.05). We can,

therefore, say that there is a tendency that the color

blue has a greater effect on alertness than the red and

white color, and red has greater effect than white.

3.3 Proposition of a New Alertness

Measure

There are known research of alertness, which uses a

very wide range of frequency analysis of EEG

signals. Chang (2013), for example, analyzed the

range of frequency covering the sum of Theta and

Alpha bands. Such an approach is justified by

New EEG Measure of the Alertness Analyzed by Emotiv EPOC in a Real Working Environment

39

individual differences in the response of EEG to

stimulus associated with alertness. However, an

excessively wide frequency range can cause

averaging of local extremes. In our experiments, the

first analysis carried out in only one band, Alpha,

did not produce statistical confirmation. In order to

try to confirm the study, we decided, therefore, to

take into account other recorded bands.

We introduced a new measure of alertness

(TAAT

max

) (1) based on the capture of signal

decreases in three bands: Theta, Alpha and

AlphaTheta. In our algorithm signals are analyzed

independently in each of these bands, and then the

biggest decrease among them is searched.

TAAT

max

= max(DIFF

T

, DIFF

A

, DIFF

AT

) (1)

Where DIFF

T

is the difference of power in Theta

band. This is calculated as power_before –

power_after. DIFF

A

is the difference of power in the

Alpha band and DIFF

AT

is the difference of power in

the AlphaTheta band, similarly calculated. Because

the decrease in signal level is correlated with an

increase in alertness, the greater the TAAT

max

the

higher the level of alertness.

3.4 Analysis of the New Measure

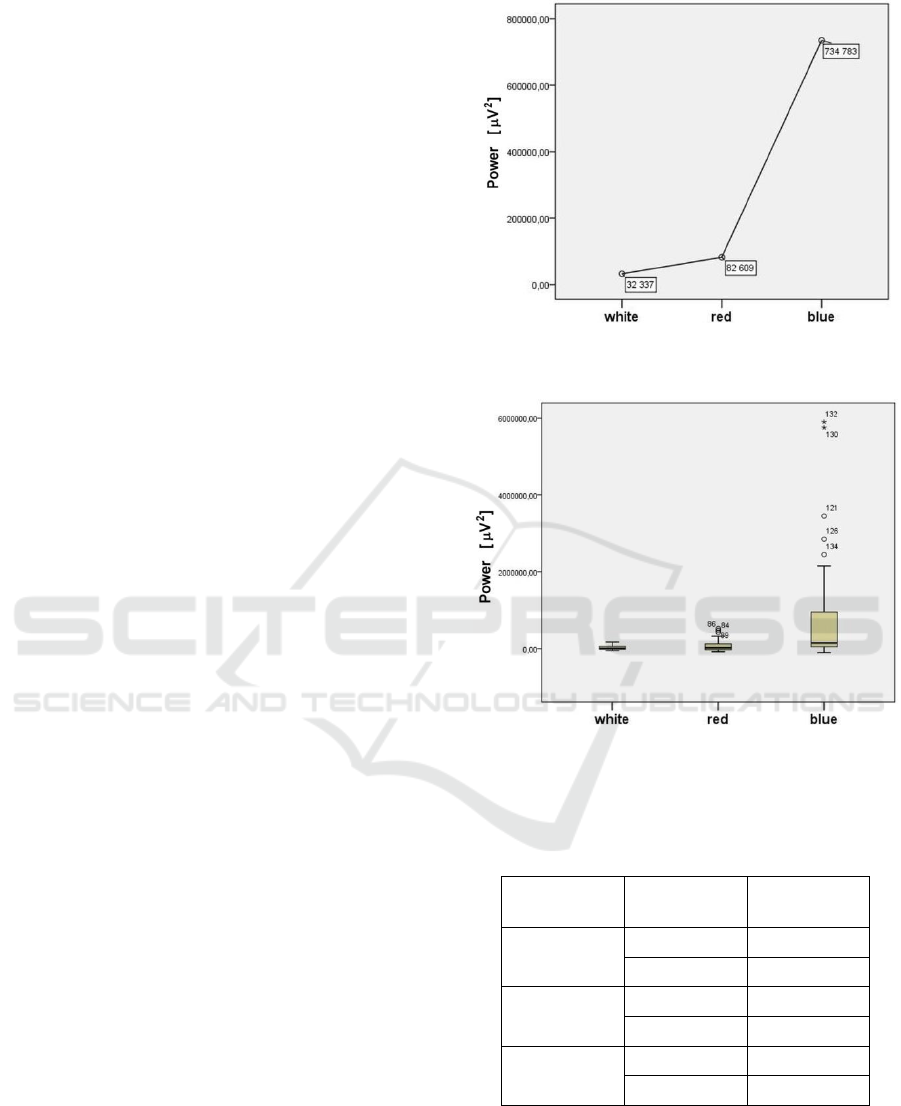

In the analysis, One Way ANOVA,

F(2, 135) = 11.04; p < 0.001, was used. Post hoc

tests and comparison of averages showed that the

greatest differences (before – after) were observed

for the blue lighting scene (Figure 3). For red and

white scenes, small differences were obtained.

Similarly, the size decrease in the EEG signal for the

blue lighting scene was the highest (Figure 4).

Gamesa-Howell post hoc tests showed that there are

statistically significant differences between the

decline for the blue lighting scene and the other two

at the level of p < 0.005 for white and p < 0.01 for

red (Table 2).

The analyses allowed the conclusion that

alertness increased after exposure under the blue

lighting scene. Also, post hoc tests and comparison

of averages showed that white lighting scene has no

elicited alertness increase, but we can see a certain

tendency for the red light in this respect. These

results are consistent with previously published

studies.

On the one hand, it has been confirmed that

alertness can be recognized from the analysis of

bands: Alpha, Theta and AlphaTheta (Chang, 2013,

Sahin and Figueiro, 2013, Baek and Min, 2015,

Klimesch, 2012, Okamoto, 2014). On the other

hand, it has been confirmed that there is a strong

Figure 3: Mean differences of TAAT

max

level decline after

exposure under particular light scenes.

Figure 4: The size of EEG signal decline using TAAT

max

measure after exposure under particular light scenes.

Table 2: Results of the ANOVA analysis for TAAT

max

measure (selection of the independent falls capture in

Alpha, AlphaTheta and Theta bands).

Lighting

scene

Lighting

scene

significance

White

Red

0.079

Blue

0.003*

Red

White

0.079

Blue

0.007*

Blue

White

0.003*

Red

0.007*

influence from blue light and a weak influence from

red on alertness, according to earlier publications

(Sahin and Figueiro, 2013, Sahin, 2014). However,

in our research the influence of red light has not

been confirmed statistically.

NEUROTECHNIX 2016 - 4th International Congress on Neurotechnology, Electronics and Informatics

40

4 CONCLUSIONS

Obtained results of measured EEG showed an

increase in alertness after 40 minutes exposure to

blue enriched white lighting modeled for normal use

in office working. It was also stated that red

enriched white lighting could increase the alertness,

but much less than was the case with blue. It is

worth noting that red light influences alertness, but

in a different way than that for melatonin

suppression, as it is for blue light. However, a

statistically significant effect on alertness was

observed only for blue light. The tendency of

increasing alertness after red light exposure was also

noticed, but that effect was not statistically

significant.

Our results confirm that blue light is the most

effective in increasing alertness, even if it is only

component (significant) of the lighting spectrum.

This was stated for real working environments and

exposure to blue enriched white lighting and with

participants not having heads fixed in one position

but performing office work during exposure. Most

of the light falling on the cornea was indirect (after

multiple reflections from the environment). In the

literature (Figueiro and Rea, 2010, Hanifin et al.,

2006, Sahin and Figueiro, 2013, Sahin et al., 2014),

the exposure was to direct light from different

lighting fixtures and subjects were looking directly

at the light, so they had not performed any work

during exposure. Our study is the first attempt to

create lighting conditions suitable for increasing

alertness and also adequate for working performance

which could be applied in reality.

The research was conducted on a group of 50

participants. It is worth noting that this is the first

study on the effect of lighting on the level of

alertness, which has included such a large group of

participants.

Additionally, the study confirmed the possibility

of the use of such low-cost equipment. Despite its

disadvantages known from the literature, the Emotiv

EPOC device allowed for the correct registration of

the EEG signal. The proposed measure of the

alertness level, which is based on the analysis of the

three bands (Alpha, Theta and AlphaTheta), proved

to be sufficiently effective. The use of this measure

in our study allowed an assessment of the effect of

blue light, which was confirmed statistically.

It is worth noting that this material gathered from

research on a large group of people will allow for

the future performance of additional analyses. In our

study, we used the bands of 4–12 Hz, because such a

range is most commonly documented in the

literature connected with alertness investigations.

However, we registered many other bands of signals

for all participants. It is planned to carry out

analyses including Beta (especially LowBeta and

optionally independently HighBeta), Delta and

DeltaTheta bands. We also want to use emotions

identified by the software of Emotiv EPOC device.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This paper has been based on the results of a

research task carried out within the scope of the third

stage of the National Programme "Improvement of

safety and working conditions" partly supported in

2014–2016 --- within the scope of research and

development --- by the Ministry of Labour and

Social Policy. The Central Institute for Labour

Protection -- National Research Institute is the

Programme's main co-ordinator.

REFERENCES

Aube, M., Roby, J., Kocifaj, M. (2013): Evaluating

potential spectra impacts of various artificial lights on

melatonin suppression, photosynthesis and star

visibility. PLOS ONE. 8(7), 1-15.

Badcock, N. A., Mousikou, P., Mahajan, Y., de Lissa, P.,

Thie, J., McArthur, G. (2013). Validation of the

Emotiv EPOC® EEG gaming system for measuring

research quality auditory ERPs. PeerJ, 1, e38.

Baek, H. and Min, B. K. (2015). Blue light aids in coping

with the post-lunch dip: an EEG study. Ergonomics,

58(5), 803-810.

Brainard, G. C., Hanifin, J. P., Greeson, J. M., Byrne, B.,

Glickman, G., Gerner, E., Rollag, M. D. (2001).

Action spectrum for melatonin regulation in humans:

Evidence for a novel circadian photoreceptors. J.

Neuroscience 21, 6405-6412.

Chang, A. M., Scheer, F. A., Czeisler, C. A., Aeschbach,

D. (2013). Direct effects of light on alertness,

vigilance, and the waking electroencephalogram in

humans depend on prior light history. Sleep. 36(8),

1239-1246.

Duvinage, M., Castermans, T., Dutoit, T., Petieau, M.,

Hoellinger, T., Saedeleer, C. D., Cheron, G. (2012). A

P300-based quantitative comparison between the

Emotiv Epoc headset and a medical EEG device. In:

Proceedings of the 9th IEEE/IASTED International

Conference on Biomedical Engineering. Innsbruck,

Austria: Acta press; 2012. doi:10.2316/P.2012.764-

071.

Ekanayake, H. (2010). P300 and Emotiv EPOC: Does

Emotiv EPOC capture real EEG?” viewed 2 May

2016, http://neurofeedback.visaduma.info/emotiv

research.htm, updated version (2015) from:

New EEG Measure of the Alertness Analyzed by Emotiv EPOC in a Real Working Environment

41

http://neurofeedback.visaduma.info/EmotivResearch.p

df.

Emotiv Systems Inc. viewed 2 May 2016

http://www.emotiv.com/

EN 12464-1, (2011). Light and lighting. Lighting of work

places. Part 1. Indoor work places. European Lighting

Standard.

Fakhruzzaman, M. N., Riksakomara, E., Suryotrisongko,

H. (2015). EEG Wave Identification in Human Brain

with Emotiv EPOC for Motor Imagery. Procedia

Computer Science. 72, 269-276.

Figueiro, M. G., Rea, M. S., (2010). The effects of red and

blue light on circadian variations in cortisol, alpha

amylase and melatonin. International Journal of

Endocrinology. 2010 (Article ID 829351),

doi:10.1155/2010/829351.

Giusti, A., Zocchi, C., Rovetta, A., 2009. A Noninvasive

System for Evaluating Driver Vigilance Level

Examining Both Physiological and Mechanical Data.

IEEE Trans. on Intelligent Transportation Systems.

10(1), 127-134.

Gola, M., Magnusk, M., Szumska, I., Wróbel, A. (2013).

EEG beta band activity is related to attention and

attentional deficits in the visual performance of elderly

subjects. International Journal of Psychophysiology,

89(3), 334-341.

Górnicka, G. B. (2008). Lighting at work: environmental

study of direct effects of lighting level and spectrum

on psychophysiological variables. PhD Thesis,

Technische Universiteit Eindhoven.

Hanifin J. P, Stewart K. T., Smith P., Tanner R., Rollag

M., Brainard, G. C., (2006). High-intensity red light

suppresses melatonin. Chronobiol Int. 23(1-2), 251-

68.

Horne, J. A. and Östberg, O. A. (1976). A self-assessment

questionnaire to determine morningness-eveningness

in human circadian rhythms. International Journal of

Chronobiology. 4, 97-110.

Ji, H., Li, J., Cao, L., Wang, D. (2012, Marz). A EEG-

Based Brain Computer Interface System towards

Applicable Vigilance Monitoring. In: Foundations of

Intelligent Systems. Chapter In: Advances in

Intelligent and Soft Computing. 122, 743-749.

Klimesch, W. (2012). Alpha-band oscillations, attention,

and controlled access to stored information. Trends in

cognitive sciences. 16(12), 606-617.

Lal, S. K. I. and Craig, A. (2001). A critical review of the

psychophysiology of driver fatigue. Biological

Psychology. 55(3), 173-194.

Li, J., Yan, C. G., Xia, B., Cao, L., Wang, D. M., Sun, Y.

R. (2010). EEG-based Brain Computer Interface for

Vigilance Analysis and Estimate. In: Proceedings of

Conference on Asia-Pacific Signal and Information

Processing Association, APSIPA ASC, Singapore, 14-

17 Dec. 2010, 189-192.

Okamoto, Y., Rea, M. S., Figueiro, M. G. (2014).

Temporal dynamics of EEG activity during short- and

long-wavelength light exposures in the early morning.

BMC Res Notes, 2014; 7:113.

Pham, T. D. and Tran, D. (2012). Emotion Recognition

Using the Emotiv EPOC Device. In: LNCS 7667, 394-

399, Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg.

Rahman, S. A., Flynn-Evans, E. E., Aeschbach, D.,

Brainard, G. C., Czeisler, C. A., Lockley, S. W.

(2014). Diurnal spectral sensitivity of the acute

alerting effects of light. Sleep. 37(2), 271-281.

Ramirez, R. and Vamvakousis, Z. (2012). Detecting

Emotion from EEG Signals Using the Emotive Epoc

Device. In: LNCS 7670, 175-184. Springer-Verlag

Berlin Heidelberg.

Sahin, L. and Figueiro, M.G. (2013). Alerting effects of

short-wavelengths (blue) and long – wavelengths (red)

lights in the afternoon. Physiology & Behaviour. 116-

117(5), 1-7.

Sahin, L., Wood, B.M., Plitnick, B., Figueiro, M.G.

(2014). Daytime light exposure: effects on biomarkers,

measure of alertness and performance. Behavioural

Brain Research. 274(1 November), 176-185.

Stytsenko, K., Jablonskis, E., & Prahm, C. (2011, August).

Evaluation of consumer EEG device Emotiv EPOC.

In: Proceedings of MEi: CogSci Conference 2011.

Thapan, K., Arendt, J., Skene, D. (2001). An action

spectrum for melatonin suppression: Evidence for a

novel non-rod. non-cone photoreceptor system in

humans. J. Physiol. 535, 261-267.

Viola, A.U., James, L.M., Schlangen, L.J., Dijk, D.J.

(2008). Blue-enriched white light in the workplace

improves self-reported alertness, performance and

sleep quality. Scand J Work Environ Health. 34(4),

297-306.

Wolska, A. and Sawicki, D. (2015). Melanopic lux and

blue light under different lighting scenarios. In:

Proceedings of the 28th Session of the CIE, June 28 -

July 4, 2015, Manchester UK. Vol.1, Part 2, 1238-

1243.

Zhan, Z. and Mu, Z. (2013). Vigilance Degree Computing

based on EEG. Telkomnika. 11(9), 5409-5414.

NEUROTECHNIX 2016 - 4th International Congress on Neurotechnology, Electronics and Informatics

42