Physiology-based Recognition of Facial Micro-expressions using EEG

and Identification of the Relevant Sensors by Emotion

Mohamed S. Benlamine

1

, Maher Chaouachi

1

, Claude Frasson

1

and Aude Dufresne

2

1

Computer Science and Operations Research, University of Montreal, Montreal, Qc, Canada

2

Communication Department, University of Montreal, Montreal, Qc, Canada

Keywords: Emotions Recognition, Physiological Signal EEG, Facial Expressions, Models Construction.

Abstract: In this paper, we present a novel work about predicting the facial expressions from physiological signals of

the brain. The main contributions of this paper are twofold. a) Investigation of the predictability of facial

micro-expressions from EEG. b) Identification of the relevant features to the prediction. To reach our

objectives, an experiment was conducted and we have proceeded in three steps: i) We recorded facial

expressions and the corresponding EEG signals of participant while he/she is looking at pictures stimuli

from the IAPS (International Affective Picture System). ii) We fed machine learning algorithms with time-

domain and frequency-domain features of one second EEG signals with also the corresponding facial

expression data as ground truth in the training phase. iii) Using the trained classifiers, we predict facial

emotional reactions without the need to a camera. Our method leads us to very promising results since we

have reached high accuracy. It also provides an additional important result by locating which electrodes can

be used to characterize specific emotion. This system will be particularly useful to evaluate emotional

reactions in virtual reality environments where the user is wearing VR headset that hides the face and makes

the traditional webcam facial expression detectors obsolete.

1 INTRODUCTION

1.1 Context and Motivation

Affective Computing (Picard, 1997) is the general

frame-work that considers emotions in human

computer interaction. In particular, the overall

objective is to make computers able to perceive, feel

and express emotions. However an important goal

remains to detect human emotions. Several studies

have been successfully conducted to detect emotions

using models that track facial expressions with

camera or webcam with, for instance, CERT

(Littlewort et al., 2011), or FaceReader (Lewinski,

den Uyl and Butler, 2014)…etc. The obtained results

in these studies showed a high accuracy that has

never been reached with other approaches using

physiological data.

The joint efforts of researchers in machine

learning, affective computing, physiological compu-

ting (Fairclough, 2010) and neuroscience are produ-

cing innovative methods for emotional and affective

states recognition by analysing data collected with

subjective methods (self-report, expert annotation)

or objective methods (log files, Kinect, camera, eye-

tracking and electrophysiology-cal sensors: EDA,

HR, EMG, EEG, Respiration rate,…) .

Thanks also to breakthrough advancements in

computer vision, facial expressions detection

technology has reached commercial-level maturity

and has become more common, e.g. with Kinect 2 in

Xbox, software like Facereader, iMotions FACET,

and NVISO. However, so far, all the focus has been

on external assessment methods and to the best of

our knowledge, no attempt has ever been made at

detecting facial micro-expressions from EEG signal.

A micro-expression (Ekman, 2007) is a brief

spontaneous facial expression, unconscious (invo-

luntary) and hard to hide as it lasts between 1/24 and

1/15 of a second. Because of their short duration,

micro-expressions are identifiable only by trained

peoples or in videos where the person's face is

recorded. Software like FACET and FaceReader

analyses videos frame by frame to extract the micro-

expressions.

Micro-expressions are important because they

give the spontaneous emotions of the users, which

can be detected using facial expression software.

However, it is not always possible to record the

person’s face; for example with low luminosity or

130

Benlamine, M., Chaouachi, M., Frasson, C. and Dufresne, A.

Physiology-based Recognition of Facial Micro-expressions using EEG and Identification of the Relevant Sensors by Emotion.

DOI: 10.5220/0006002701300137

In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Physiological Computing Systems (PhyCS 2016), pages 130-137

ISBN: 978-989-758-197-7

Copyright

c

2016 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

when the person is moving his face or when he is

using VR headset to interact with an immersive

virtual reality environment. In such situations,

physiological measures like EEG represent a

promising alternative that could potentially solve

these problems. Moreover EEG devices are being

increasingly used as they present a practical low cost

solution and help building interesting accurate

models to track and assess users’ states. EEG

features can improve recognition of affect and facial

expressions.

Recent studies in the field of neuroscience have

found a relation between neural activations and

emotions using the technique of Functional

Magnetic Resonance Imaging, or fMRI. For

example, (Kassam, Markey, Cherkassky, Loewen-

stein and Just, 2013) show, through an experiment

with 10 participants using fMRI, that there are

consistent patterns of neural activation for all

emotion categories within and between participants.

In the meanwhile, several works has shown that

emotional states can be recognized from EEG signal

with reasonable accuracy (AlZoubi, Calvo and

Stevens, 2009; Chaouachi, Chalfoun, Jraidi and

Frasson, 2010; Chaouachi and Frasson, 2012;

Chaouachi, Jraidi, and Frasson, 2015; Heraz and

Frasson, 2007; Jraidi, Chaouachi and Frasson, 2013;

Liu, Sourina and Nguyen, 2011; Lu, Zheng, Li and

Lu, 2015). So, it seems sensible then to consider

cerebral activity as input for detecting facial

expressions rather than user’s face images or videos.

All this leads us to believe that a correlation between

EEG features and facial micro-expressions should be

investigated.

1.2 Objectives

Knowing now the importance of micro-expressions

for emotion detection, we aim to build a predictive

model of these emotional micro-expressions from

EEG signals. With such a model, it will be possible

to predict spontaneous facial expressions having as

input cerebral activity signal using Emotiv Headset.

More precisely, we aim to answer two questions:

(1) How well can we predict facial expressions from

the brain signals of participants? (2) Which EEG

features are important for the prediction?

To reach these objectives, we will proceed

according to the following steps: 1) measuring

emotional reactions of a user confronted to specific

emotional pictures using FACET system, 2)

measuring the corresponding EEG signals and train

machine learning models that correlates the micro-

expressions with the EEG signals, and 3) predict the

emotion only from the model and check the

accuracy of the model.

The organization of this paper is as follows:

section 2 presents the design of our experimental

approach and methodology for the EEG-based facial

expressions recognition. We show how we can

evaluate emotions using a well-known set of

emotional pictures. We detail the material used for

the experimentation and the different measures

obtained. Results and discussions are presented in

section 3. We finally show how our model can

predict the micro-expressions from EEG signals. We

conclude this study with a presentation of the scope

of use of this model as well as our future work.

2 METHODS

2.1 Participants

Twenty participants (7 women, 13 men) were

recruited for our study. Their ages ranged from 21 to

35 years and all of them came from a North

American University. All participants were right

handed and comparable in age, sex and education.

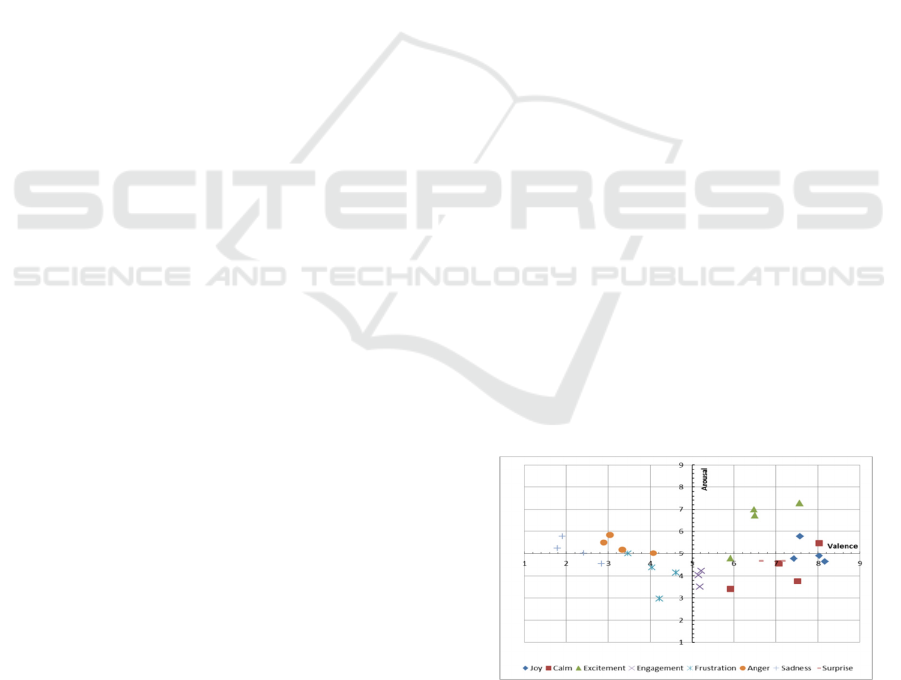

2.2 IAPS Pictures Selection

We selected 30 pictures from IAPS (International

Affective Picture System) (Lang, Bradley and

Cuthbert, 2008) with regard to their affective ratings

(valence, arousal) after consulting the IAPS

documentation. The selected pictures are well

distributed throughout the space (Figure 1). We

grouped those pictures in 8 emotion categories: Joy,

Calm, Excitement, Engagement, Frustration, Anger,

Sadness, and Surprise.

Figure 1: IAPS pictures’ affective ratings distribution and

their categories of emotion.

2.3 Experimental Procedure

The participants were received and introduced to our

Physiology-based Recognition of Facial Micro-expressions using EEG and Identification of the Relevant Sensors by Emotion

131

laboratory. A consent form was given to the

participant to read and sign it in order to register his

agreement about doing the experiment. They were

seated in front of a computer and a webcam. The

participant’s chair was adjusted to maintain good

view of their faces to the webcam.

The experiment design was synchronized by

iMotions Attention Tool which is a software plat-

form that permit multi-sensors study (eye tracking,

facial expressions detection, EEG, GSR …) with

automatic synchronization. We have recorded data

of facial expressions using FACET module and EEG

using Emotiv Epoch headset. IAPS Pictures with the

same emotion category were displayed 6 seconds

one by one, separated by a noise screen of 5 seconds

to accomplish a relaxation phase before the

projection of the next picture. After that, a form

appears asking the user to choose one from the eight

emotion categories that best represent his global

feeling about the previewed pictures. The same

procedure was repeated for each of the eight

emotion categories. The goal of this form is to have

the user’s subjective confirmation of the emotion

he/she supposed to feel seeing the pictures. The

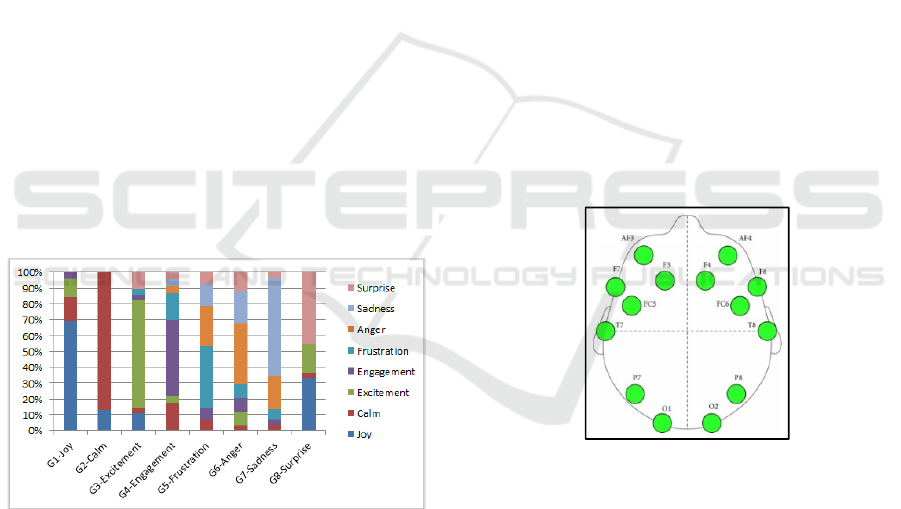

chart below (Figure 2) shows the percent of the self-

reported emotion categories by the IAPS pictures

groups. We configured FACET to analyse frame by

frame the videos of the user’s face to extract his/her

micro-expressions.

Figure 2: Self-reported emotions by pictures groups.

2.4 Measures and Materials

In this study, we have used the following tools.

2.4.1 iMotions FACET Module

The FACET module detects and tracks facial

expressions of primary emotions using real-time

frame-by-frame analysis of the emotional responses

of users via a webcam. A commercial webcam is

used for the user face recording (Webcam Logitech

Pro C920). The captured image is 1920 x 1080

pixels with 24-bit RGB colours, acquired at 6

frames/sec. The FACET module is the commercial

version of CERT (Computer Expression Recognition

Toolbox) (Littlewort et al., 2011) which is a robust

facial micro-expressions recognition software with

an accuracy that reaches 94% (Emotient, 2015). The

resulted data file contains two columns (Evidence

and Intensity) for-each of the following categories:

Joy, Anger, Surprise, Fear, Contempt, Disgust,

Sadness, Neutral, Positive Valence, and Negative

Valence.

2.4.2 Emotiv EPOCH EEG

Physiological data were recorded during the session

using the Emotiv EEG headset. The headset contains

14 electrodes that must be moist with a saline

solution (Contact lens cleaning solution). The

electrodes are spatially organized with respect to the

International 10–20 system. They are located at

AF3, F7, F3, FC5, T7, P7, O1, O2, P8, T8, FC6, F4,

F8, and AF4 (see Figure 3) with two other reference

nodes (that would be placed behind the ears). The

generated data are in µVolt with a sampling rate of

128 Samples/sec. The signal’s frequencies are

between 0.2 and 60Hz.

Figure 3: Data channels placement of the Emotiv Headset.

3 DATA ANALYSIS

3.1 Facial Expressions Data

Taking the webcam stream as input, the FACET

system classifies each frame and provides two

values for each emotion category, namely: Evidence

and Intensity. The Intensity number is a value

between 0 and 1, which denotes the estimation by

expert human coders of the intensity of an

expression. While the Evidence number is a value

between -3 and 3 that represents the presence of an

expression. For an easier interpretation, the

PhyCS 2016 - 3rd International Conference on Physiological Computing Systems

132

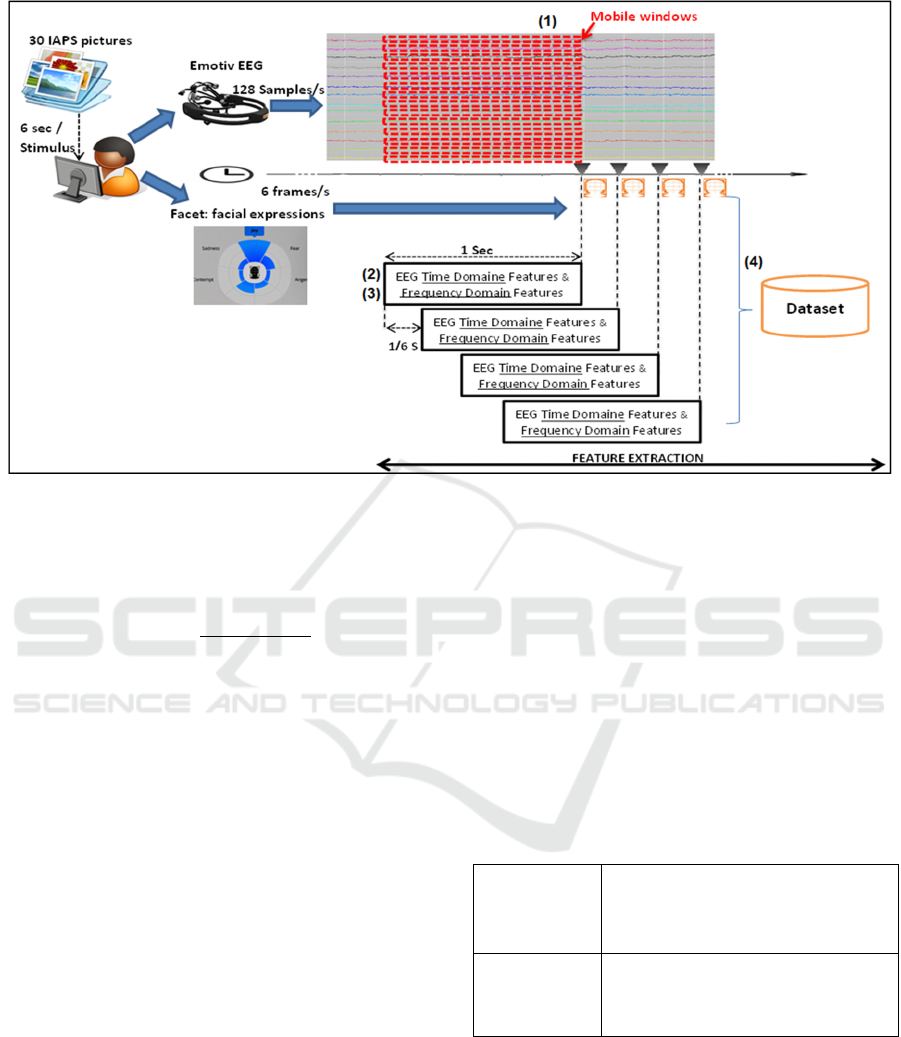

Figure 4: Pipeline of dataset construction for EEG-based Facial Expressions recognition.

Evidence number has been transformed into emotion

probability between 0 and 1, using this formula (as

in FACET guide) (Facet, 2013):

(1)

We computed the probability of each emotion in

our dataset. These probabilities will be considered as

ground truth in the models training phase.

3.2 Dataset Creation

Building the dataset is an important process that has

a big impact in the robustness and the accuracy of

the resulting machine learning models.

The figure above (Figure 4) illustrates the entire

pipeline that we have designed for the construction

of our dataset for EEG-based Facial Expressions

recognition. We developed a java program that uses

14 first-in first-out queues of size 128 of reals as

mobile windows of 1 second EEG data from each

electrode (each window contains 128 samples). (1)

For each FACET frame time (every 1/6 sec) the

program reads the content of each window and (2)

performs statistical analysis to extract time-domain

features and (3) spectral analysis to extract

frequency-domain features. (4) The program records

in a separate CSV file the FACET frame Time, the

computed Time-domain and Frequency-domain

features of each electrode (Table 1) and the

probability value of each emotion category.

The frequency-domain features are computed by

applying FFT on the 128 samples contained in each

window for each FACET Frame Time. By using the

Fast Fourier transform (FFT), we calculated the

magnitudes (in µV²) in frequency domain for the

corresponding frequency bands (delta [1–4 Hz[,

theta [4–8 Hz[, alpha [8–12 Hz[, beta [12–25 Hz[,

and gamma [25–40 Hz[ ) with the application of

hamming window to smooth the signal. The FACET

frame rate is 6 frames per second, so each window

receives, every 1/6 sec, 22 new EEG values

(128/6=21.33 ~ 22).

Table 1: Computed features from EEG Signals.

Frequency-

domain EEG

Features (5

Features)

delta [1–4 Hz[, theta [4–8 Hz[, alpha

[8–12 Hz[, beta [12–25 Hz[, and

gamma [25–40 Hz[

Time-domain

EEG Features

(12 Features)

Mean, Standard Error, Median, Mode,

Standard Deviation, Sample Variance,

Kurtosis, Skewness, Range, Minimum,

Maximum and Sum

The time-domain features (Table 1) are also

computed based on each window that contains 128

samples for each FACET Frame time. Therefore, the

used epoch length in this study is 128 samples. The

twelve features of the EEG signal indicated above

are extracted in the time domain. For each FACET

Frame time, we computed from each window:

Minimum, Maximum, Mean and Sum values. The

Range represents the difference between the

Physiology-based Recognition of Facial Micro-expressions using EEG and Identification of the Relevant Sensors by Emotion

133

Minimum and Maximum. The Mode is the most

commonly occurring value. The Variance measures

the spread between the values in the window and the

Mean. A variance of zero indicates that all the

values are identical. The standard deviation is the

square root of the variance. The standard Error is the

standard deviation divided by the square root of the

window size.

Kurtosis is a descriptor of the shape of a

distribution which represents the distribution's width

of peak. A Gaussian distribution has a kurtosis of

zero; a flatter distribution has a negative kurtosis,

and a more peaked distribution has a positive

kurtosis. Skewness is a measure of the asymmetry of

a distribution relative to its mean; a distribution can

be negatively skewed when the left tail is longer or

positively skewed when the right tail is longer, and a

symmetrical distribution has a skewness of zero.

We have not used a window containing average

values from all electrodes because we assumed that

each emotion has its own activated area in the brain

(Kassam et al., 2013). The Machine learning

algorithms will select features from the suitable

electrodes for the prediction of specific emotion

category values.

The total number of computed features from all

the electrodes is 238 (17 features per electrode: 5

frequency-domain features + 12 time-domain

features). The collected dataset contains 21553 data

points (1078 data point per participant; 36 data point

per stimulus). We have created 10 CSV files where

we put together all the extracted EEG Features and

one emotion category extracted from FACET data.

Each file was entered as an input to the WEKA ma-

chine learning toolkit (Hall et al., 2009) for

generating EEG-based regression model to predict

the values of one emotion category.

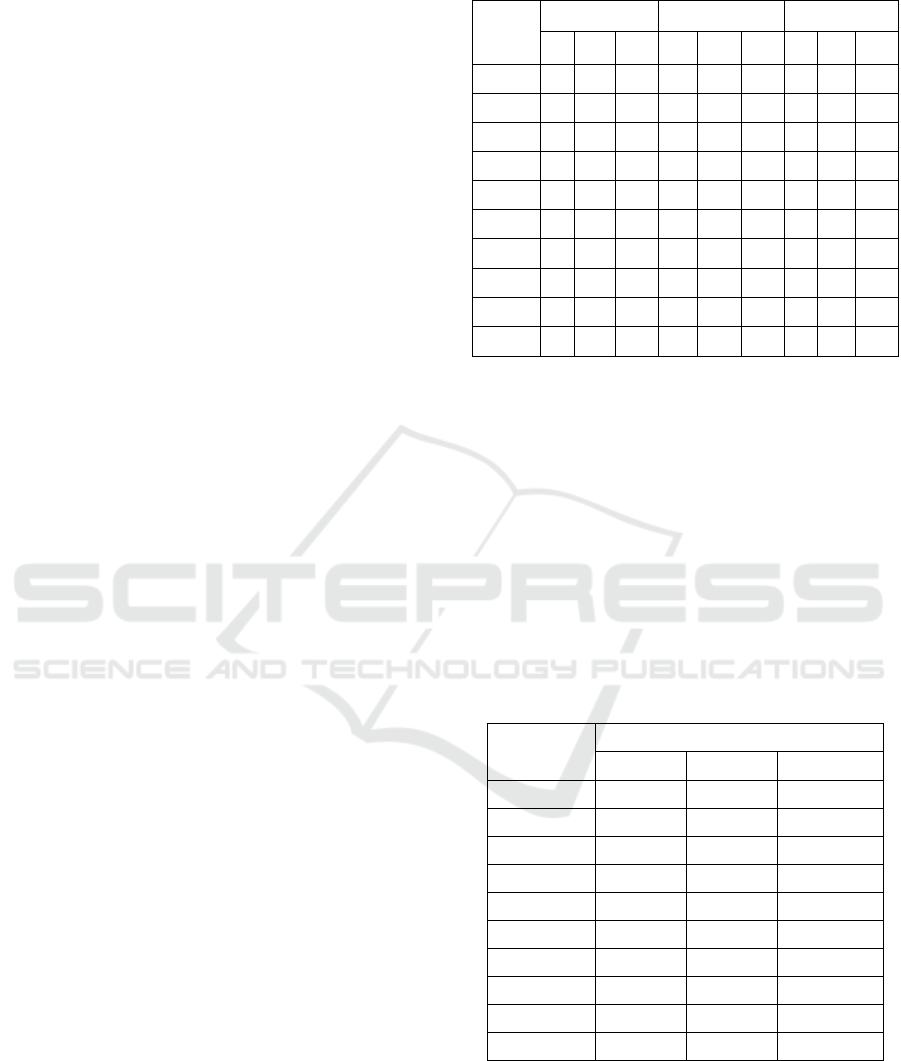

4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

For every one of the 10 emotion categories, a

regression model was generated. Three machine

learning algorithms were used to predict the numeric

values of each emotion category; namely IBk (K-

nearest neighbours classifier), Random Forest

(classifier constructing a forest of random trees) and

RepTree (Fast decision tree learner).We used 10 fold

validation in our test phase. For the prediction of the

emotion classes’ values, we have chosen dependent

criteria: Correlation Coefficient (CC), Mean

Absolute Error (MAE) and Root Mean Squared

Error (RMSE) to evaluate the goodness of different

machine learning algorithms.

Table 2: Comparison between machine learning methods.

Emotion

IBk Random Forest RepTree

CC MAE RMSE CC MAE RMSE CC MAE RMSE

Joy

0.85 0.02 0.05 0.91 0.02 0.05 0.72 0.03 0.07

Anger

0.88 0.05 0.09

0.92

0.05 0.08 0.83 0.07 0.10

Surprise

0.85 0.02 0.04 0.90 0.02 0.03 0.76 0.02 0.05

Fear

0.89 0.04 0.08

0.92

0.05 0.07 0.78 0.07 0.10

Neutral

0.87 0.05 0.10 0.91 0.06 0.09 0.74 0.08 0.14

Contempt

0.79 0.03 0.07 0.85 0.04 0.06 0.63 0.05 0.08

Disgust

0.88 0.03 0.06

0.92

0.03 0.05 0.63 0.05 0.08

Sadness

0.89 0.03 0.06

0.92

0.03 0.06 0.83 0.04 0.08

Positive

0.85 0.05 0.11 0.91 0.06 0.09 0.76 0.08 0.13

Negative

0.86 0.10 0.16 0.90 0.11 0.14 0.80 0.13 0.18

Compared to IBk (k=1 neighbour) and RepTree

methods, Random Forest obtains higher correlation

coefficient and lower error rates such as MAE and

RMSE for all emotion categories, as illustrated in

Table 2.

In order to find the optimal EEG features for

each emotion category, we used a feature selection

method called ReliefF over Random forest algorithm

to choose an optimal feature set of size 24 (10% of

the initial features set). The experimental results

performed on the different emotion categories are

presented in Table 3.

Table 3: Random forest models results with reliefF feature

selection method.

Emotions

R.F. (selection of 24 Attributes)

CC MAE RMSE

Joy

0.8336 0.0266 0.0585

Anger

0.8888 0.0612 0.0872

Surprise

0.8272 0.0219 0.0428

Fear

0.8949 0.0516 0.0744

Neutral

0.8854 0.0648 0.0971

Contempt

0.8266 0.0374 0.0607

Disgust

0.9196 0.0307 0.0483

Sadness

0.8854 0.0401 0.0640

Positive

0.8647 0.0655 0.1012

Negative

0.8878 0.1093 0.1439

In the experiments, a 10-fold cross validation

method was used for evaluation. It is notable that

Random Forest method performs well even with 24

features. The 24 selected EEG features by emotion

category are presented in Table 4.

PhyCS 2016 - 3rd International Conference on Physiological Computing Systems

134

Table 4: The selected 24 attributes by ReliefF over

Random Forest for each emotion category.

Emotion

The selected 24 attributes (10% of

features set)

Joy

P8_Mode, T8_Mode, P8_Range,

T8_Minimum, T8_Range, P8_Maximum,

T8_Maximum, T8_Standard_Deviation,

T8_Standard_Error, P8_Minimum,

T8_Median, P8_Median, T8_Sum,

T8_Mean, FC6_Standard_Error,

FC6_Standard_Deviation, FC6_Minimum,

P8_Standard_Error,

P8_Standard_Deviation, T8_Delta,

P8_Mean, P8_Sum, T8_Beta, P7_Range

Anger

P7_Range, P8_Range, P8_Maximum,

P7_Standard_Deviation,

P7_Standard_Error, P8_Mode,

P8_Minimum, P7_Maximum, AF4_Range,

P8_Median, AF3_Mode, F3_Range,

T7_Skewness, P7_Gamma,

P8_Standard_Error,

P8_Standard_Deviation, P7_Median,

P7_Beta, P7_Alpha, P8_Sum, P8_Mean,

AF3_Maximum, P7_Mode, P7_Delta

Surprise

P7_Mode, P7_Range, P7_Maximum,

P8_Skewness, P7_Minimum,

P7_Standard_Error,

P7_Standard_Deviation, P7_Kurtosis,

P7_Median, P7_Sum, P7_Mean,

P8_Kurtosis, P7_Skewness,

T7_Sample_Variance, T7_Mode,

P8_Minimum, T7_Standard_Deviation,

T7_Standard_Error, T7_Kurtosis,

P7_Sample_Variance, O1_Skewness,

O2_Kurtosis, F8_Kurtosis, O1_Kurtosis

Fear

FC6_Standard_Error,

FC6_Standard_Deviation, FC6_Minimum,

P8_Range, P8_Minimum, FC5_Minimum,

FC6_Range, P8_Maximum, P7_Range,

T8_Minimum, P8_Median,

FC5_Standard_Error,

FC5_Standard_Deviation, P8_Mean,

P8_Sum, P8_Standard_Deviation,

P8_Standard_Error, FC6_Delta, T7_Delta,

FC6_Sample_Variance, FC6_Mode,

P8_Mode, T7_Skewness, P7_Skewness

Neutral

P8_Mode, P8_Range, P8_Maximum,

T8_Mode, P8_Minimum, T8_Minimum,

T8_Range, T8_Maximum, P8_Median,

P8_Mean, P8_Sum, P8_Standard_Error,

P8_Standard_Deviation, P7_Range,

FC5_Minimum, T8_Standard_Deviation,

T8_Standard_Error, FC6_Mode,

FC6_Standard_Deviation,

FC6_Standard_Error, FC6_Range,

FC6_Minimum, P8_Theta,

FC5_Standard_Error

Contempt

T8_Mode, P8_Mode, T8_Minimum,

FC6_Mode, F7_Minimum,

FC6_Standard_Error,

FC6_Standard_Deviation, FC6_Minimum,

FC6_Range, FC5_Minimum, T7_Delta,

FC5_Mode, T8_Maximum, F8_Mode,

T8_Range, F7_Range, F7_Mode,

FC6_Delta, F8_Range,

FC5_Standard_Error,

FC5_Standard_Deviation, F7_Maximum,

T7_Beta, F8_Minimum

Disgust

P8_Maximum, P8_Mode, P8_Range,

P7_Range, P8_Minimum, P8_Median,

P8_Mean, P8_Sum,

P8_Standard_Deviation,

P8_Standard_Error, O1_Minimum,

AF4_Range, FC5_Minimum,

AF4_Minimum, F7_Minimum,

P7_Standard_Deviation,

P7_Standard_Error, P7_Maximum,

F8_Maximum, FC5_Standard_Error,

FC5_Standard_Deviation, T7_Skewness,

AF4_Standard_Deviation,

AF4_Standard_Error

Sadness

P8_Range, P8_Maximum, P8_Mode,

P8_Minimum, P7_Range,

P8_Standard_Deviation,

P8_Standard_Error, P8_Median, P8_Beta,

P8_Theta, P8_Sum, P8_Mean, P8_Alpha,

P7_Kurtosis, P8_Gamma, P7_Maximum,

AF3_Range, P7_Standard_Deviation,

P7_Standard_Error, P8_Delta,

AF3_Minimum, AF3_Maximum,

P8_Sample_Variance, P8_Skewness

Positive

P8_Mode, T8_Mode, T8_Minimum,

T8_Range, P8_Range, P8_Maximum,

T8_Maximum, P8_Minimum,

T8_Standard_Deviation,

T8_Standard_Error,

FC6_Standard_Deviation,

FC6_Standard_Error, P7_Range,

T8_Median, FC6_Range, T8_Sum,

T8_Mean, FC6_Minimum, T8_Beta,

FC6_Mode, P8_Median,

P8_Standard_Error,

P8_Standard_Deviation, T8_Delta

Negative

P8_Range, P8_Maximum, P8_Minimum,

P7_Range, F7_Minimum, P8_Median,

P8_Sum, P8_Mean, P8_Standard_Error,

P8_Standard_Deviation, F3_Range,

T8_Minimum, T8_Range,

F7_Standard_Error,

F7_Standard_Deviation, F7_Range,

P7_Gamma, AF4_Range, FC5_Mode,

P7_Standard_Error,

P7_Standard_Deviation, FC5_Minimum,

P7_Maximum, FC6_Standard_Deviation

Physiology-based Recognition of Facial Micro-expressions using EEG and Identification of the Relevant Sensors by Emotion

135

From the results in Table 4, we have identified

the most suitable EEG electrodes by emotion

category as illustrated in Table 5.

Table 5: Random Forest selected EEG electrodes by

emotion category.

Emotion Selected Electrodes

Joy

P8, T8, FC6

Anger

P7, P8, AF4, AF3, F3, T7

Surprise

P7, P8, T7, O1, O2, F8

Fear

FC6, P8, FC5, FC6, P7, T8, T7

Neutral

P8, T8, P7, FC5, FC6

Contempt

T8, P8, FC6, FC5, T7, F8, F7

Disgust

P8, P7, O1, AF4, FC5, F7, F8, T7

Sadness

P8, P7, AF3

Positive

P8, T8, FC6, P7

Negative

P8, P7, F7, F3, T8, AF4, FC5, FC6

These results are very important, since this is the

first time we identify the most reliable sensors for

each emotion category. In previous study, Liu and

colleagues (Liu et al., 2011) implemented a real-time

EEG-based emotion recognition algorithm based on

fractal dimension calculation of six different

emotions using only AF3, F4 and FC6 electrodes.

Our proposed model has better accuracy, more

adaptability to all users and several advantages

besides. In fact, the identification of the most active

electrodes detected by our model gives us a deep

understanding of how the brain reacted with regard

to emotional elicitation. Furthermore, we note that

the P8 is a common electrode for all emotion

categories. The P8 sensor position is localized on the

parietal lobe of the right cerebral hemisphere of the

brain. This result is consistent with the study of

Sarkheil and his colleagues (Sarkheil, Goebel,

Schneider and Mathiak, 2013), and confirms the role

of the right IPL (Inferior Parietal Lobule) in

decoding dynamic facial expressions. So, the right

IPL is not only involved in decoding the others’

facial expressions but also in generating our own

facial expressions. The same consistency holds for

the F4 sensor that was completely excluded by our

model and F3 sensor that was only used to detect

Anger and Negative emotions. In fact, the two

sensors are located in the frontal lobe which is,

according to the study of Lough et al. (Lough et al.,

2006), related to the modification of emotions to

generally fit socially acceptable norms.

With these results, our EEG-based facial

expressions prediction approach provides a simple

and reliable way to capture the emotional reactions

of the user that can be used in learning, games,

neurofeedback, and VR environments.

5 CONCLUSION

This work shows that user’s facial expressions are

predictable from EEG physiological signals. The

emotion recognition problem is considered from

regression perspective taking as ground truth the

detected facial expressions’ data from webcam-

based facial expressions recognition software

(FACET). The experiment results revealed that

facial expressions can be recognizable from specific

EEG sensors by the mean of specific time-domain

and frequency-domain features. Our experimental

design and features construction method has

enhanced the physiological emotions recognition

accuracy reaching performances similar to computer

vision technics. This finding suggests that the used

EEG features were sufficiently implemented for the

prediction of facial expressions from EEG with high

accuracy. This accuracy is compared with FACET

output and not against the self-reported emotional

state of the user which is out of the scope of this

current study and would be an interesting direction

for further work with larger sample size. With the

advances in the technology of EEG and appearance

of new EEG headsets with dry sensors and wireless

transmission of physiological data to mobile

applications (Chi et al., 2012; Samsung, 2015),

emotions assessment with EEG equipment will be

more common in our daily life. Therefore, we are

considering the integration of our models in a virtual

reality environment to test their performances in

real-time conditions and detect the user’s facial

reactions even with VR headset that hides his face.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The research presented in this paper has been

supported by funding awarded by the Natural

Sciences and Engineering Research Council of

Canada (NSERC) and Beam Me Up Games.

REFERENCES

AlZoubi, Omar, Calvo, Rafael A and Stevens, Ronald H.

(2009). Classification of EEG for affect recognition:

an adaptive approach AI 2009: Advances in Artificial

Intelligence (pp. 52-61): Springer.

PhyCS 2016 - 3rd International Conference on Physiological Computing Systems

136

Chaouachi, Maher, Chalfoun, Pierre, Jraidi, Imène and

Frasson, Claude. (2010). Affect and mental engage-

ment: towards adaptability for intelligent systems.

Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 23rd

International FLAIRS Conference, Daytona Beach,

FL. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download.

Chaouachi, Maher and Frasson, Claude. (2012). Mental

workload, engagement and emotions: an exploratory

study for intelligent tutoring systems. Paper presented

at the Intelligent Tutoring Systems.

Chaouachi, Maher, Jraidi, Imène and Frasson, Claude.

(2015). MENTOR: A Physiologically Controlled

Tutoring System User Modeling, Adaptation and

Personalization (pp. 56-67): Springer.

Chi, Yu Mike, Wang, Yu-Te, Wang, Yijun, Maier,

Christoph, Jung, Tzyy-Ping and Cauwenberghs, Gert.

(2012). Dry and noncontact EEG sensors for mobile

brain–computer interfaces. Neural Systems and

Rehabilitation Engineering, IEEE Transactions on,

20(2), 228-235.

Ekman, Paul. (2007). Emotions revealed: Recognizing

faces and feelings to improve communication and

emotional life: Macmillan.

Emotient. (2015). Emotient Accuracy Measures and

Methodology. Retrieved from Emotient.com website:

http://www.emotient.com/wp-content/uploads/Emoti

ent-Accuracy-Methods-May-2015.pdf

Facet, iMotions. (2013). Attention Tool FACET Module

Guide Retrieved from imotions.com website:

https://imotions.com/wp-

content/uploads/2013/08/130806_FACET_Guide.pdf

Fairclough, Stephen H. (2010). Physiological computing:

interfacing with the human nervous system Sensing

emotions (pp. 1-20): Springer.

Hall, Mark, Frank, Eibe, Holmes, Geoffrey, Pfahringer,

Bernhard, Reutemann, Peter and Witten, Ian H.

(2009). The WEKA data mining software: an update.

ACM SIGKDD explorations newsletter, 11(1), 10-18.

Heraz, Alicia and Frasson, Claude. (2007). Predicting the

three major dimensions of the learner’s emotions from

brainwaves. World Academy of Science, Engineering

and Technology, 31, 323-329.

Jraidi, Imène, Chaouachi, Maher and Frasson, Claude.

(2013). A dynamic multimodal approach for assessing

learners' interaction experience. Paper presented at

the Proceedings of the 15th ACM on International

conference on multimodal interaction.

Kassam, K. S., Markey, A. R., Cherkassky, V. L.,

Loewenstein, G. and Just, M. A. (2013). Identifying

Emotions on the Basis of Neural Activation. Plos One,

8(6). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066032

Lang, Peter J, Bradley, Margaret M and Cuthbert, Bruce

N. (2008). International affective picture system

(IAPS): Affective ratings of pictures and instruction

manual. Technical report A-8.

Lewinski, Peter, den Uyl, Tim M and Butler, Crystal.

(2014). Automated facial coding: Validation of basic

emotions and FACS AUs in FaceReader. Journal of

Neuroscience, Psychology, and Economics, 7(4), 227.

Littlewort, Gwen, Whitehill, Jacob, Wu, Tingfan, Fasel,

Ian, Frank, Mark, Movellan, Javier and Bartlett,

Marian. (2011).

The computer expression recognition

toolbox (CERT). Paper presented at the Automatic

Face & Gesture Recognition and Workshops (FG

2011), 2011 IEEE International Conference on.

Liu, Yisi, Sourina, Olga and Nguyen, Minh Khoa. (2011).

Real-time EEG-based emotion recognition and its

applications Transactions on computational science

XII (pp. 256-277): Springer.

Lough, Sinclair, Kipps, Christopher M, Treise, Cate,

Watson, Peter, Blair, James R and Hodges, John R.

(2006). Social reasoning, emotion and empathy in

frontotemporal dementia. Neuropsychologia, 44(6),

950-958.

Lu, Yifei, Zheng, Wei-Long, Li, Binbin and Lu, Bao-

Liang. (2015). Combining eye movements and EEG to

enhance emotion recognition. Paper presented at the

International Joint Conference on Artificial

Intelligence (IJCAI).

Picard, Rosalind W. (1997). Affective computing (Vol.

252): MIT press Cambridge.

Samsung. (2015). Samsung prototypes brainwave-reading

wearable stroke detector. Retrieved from Samsung

Tomorrow website: https://news.samsung.com/global/

c-lab-engineers-developing-wearable-health-sensor-

for-stroke-detection

Sarkheil, Pegah, Goebel, Rainer, Schneider, Frank and

Mathiak, Klaus. (2013). Emotion unfolded by motion:

a role for parietal lobe in decoding dynamic facial

expressions. Social cognitive and affective

neuroscience, 8(8), 950-957.

Physiology-based Recognition of Facial Micro-expressions using EEG and Identification of the Relevant Sensors by Emotion

137