A Systematic Review of eHealth Interventions for Healthy Aging:

Status of Progress

Idrissa Beogo

1

, Phillip Van Landuyt

2

, Marie-Pierre Gagnon

1,3

and Ronald Buyl

2

1

Research Center of the Centre Hospitalier de Québec-Université Laval, 10 de l’Espinay, Quebec, Canada

2

Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Laarbeeklaan 103, Jette, Belgium

3

Faculty of Nursing Sciences, Université Laval, Québec, 1050 Avenue de la Medecine, Quebec, Canada

Keywords: eHealth, Healthy Aging, Aging, Systematic Review.

Abstract: Worldwide, old age population is projected to attained 2 billion by 2050, raising challenges for healthcare,

social security, pension and long-term care. Several eHealth interventions have been as proposed as promising

avenues to support healthy aging (HA), but effectiveness has not been synthesised. This study aims to

systematically review the effectiveness of eHealth interventions for HA. We performed standardized searches

in relevant databases to identify (quasi)-experimental studies evaluating the effectiveness of eHealth

interventions for HA. Outcomes of interest are: wellbeing, quality of life, activities of daily living, leisure

activities, knowledge, evaluation of care, social support, skill acquisition and healthy behaviours. We also

consider adverse effects such as social isolation, anxiety, and burden on informal caregivers. Two reviewers

will independently assess studies for inclusion. Data extraction is based on standardised tools and done

independently by two reviewers. An initial search led to 7039 potentially relevant citations. After screening

titles and abstract, 60 full text articles were further assessed, of which 12 (presenting 11 studies) were finally

retained for the review. Effect sizes related to each type of eHealth intervention will be calculated on the final

selection. If not possible, we will present the findings in a narrative form. This systematic review will provide

unique knowledge on the effectiveness of eHealth interventions for supporting HA.

1 INTRODUCTION

Worldwide, the proportion of people aged over 65

years is projected to attain 2 billion by 2050 (Kinsella

and Phillips, 2005). This change, associated with

progresses in healthcare but mostly with

improvements in living conditions, put aging at the

forefront of public concerns. However, population

aging also associated with an increase in the

prevalence of chronic diseases (Reis et al., 2013),

which challenges the sustainability of healthcare and

social services delivery (Illario et al., 2015). In view

of these challenges, following the World Health

Organization (WHO) meeting on healthy aging

(World Health Organization, 2002), several

initiatives has spurred, among which eHealth

Interventions for Healthy Aging.

Healthy aging (HA) is defined as “the process of

optimizing opportunities for physical, social and

mental health to enable older people to take an active

part in society without discrimination and to enjoy an

independent and good quality of life” (Swedish

National Institute of Public Health, 2006).

HA includes an active engagement with life,

optimal cognitive and physical functioning and low

risk of disease that enables older people to participate

within their limitations and continue to be physically,

cognitively, socially and spiritually active (Hansen-

Kyle, 2005). People live longer and want to stay

active, happier, and healthy although the decline in

the biological, physiological and cognitive systems

inherent to aging may limit full social, cultural and

intellectual engagement in the elderly (Jin et al.,

2015). As the first wave of baby-boomers reaches the

retirement age, policies are levied to keep seniors

active in prolonging the working period in several

countries (e.g. Greece, France, Denmark) (Hofäcker,

2014, Hofäcker and Naumann, 2015). This cohort and

onward generations in the “early old age” (50 years

and above) use e-tools in their daily activities (Pew

research Center, 2014). Ensuring HA for the

population is thus a priority in developed countries,

but also in developing countries that foresee aging of

their population in a near future (Henriquez-Camacho

et al., 2014).

eHealth is an overarching term that encompasses

122

Beogo, I., Landuyt, P., Gagnon, M-P. and Buyl, R.

A Systematic Review of eHealth Interventions for Healthy Aging: Status of Progress.

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health (ICT4AWE 2016), pages 122-126

ISBN: 978-989-758-180-9

Copyright

c

2016 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

the various uses of Information and Communication

Technology (ICT) and web-driven application in the

sphere of health care and health promotion, such as

telemedicine, electronic health records, virtual

interventions and personal health monitoring. With

respect to HA, eHealth applications offer older adults

the opportunity to access health information and

receive health and social care in their homes. These

interactive interventions can empower, engage, and

educate older adults (Hall et al., 2012). eHealth

interventions are among the promising avenue and

receive increasing attention because of their potential

to support a healthy life and the recognition of their

central role in today’s society. In synthesizing the

latest updates, Lattanzio et al. highlight three main

domains of development related to eHealth

innovation: (1) disease management, (2) intelligent

devices to address mobility risks (i.e., falls in elders),

and (3) specific needs for HA (Lattanzio et al., 2014).

In total, they are designed for virtual physical exercise

(Silveira et al., 2013, Wu and Keyes, 2006) ─

wirelessly or not─, to promote social networking

(Rébola, 2015), lifestyle (Cook et al., 2015);

smartphone application are developed to support

elderly autonomy (Willner et al., 2015). Interestingly,

recent studies contended a high intention to adopt e-

tools among older adults (Rosella et al., 2014) as well

as a recognition of their safety (Heinbuchner et al.,

2010, Londei et al., 2009), and their relevance

(Mihailidis et al., 2008). Some other reported that

they are adapted and usable and offer independence

and confidence (Brownsell and Hawley, 2004).

eHealth is evolving rapidly. In the first quarter of

2014 the number of health and wellbeing apps has

reached the cape of 100.000 (Research2guidance,

2014), targeting predominantly chronically ill

patients (31%) and health and fitness-interested

people (28%). Approximately, 500 million

smartphone users worldwide will be using a

healthcare application by the end of 2015. A

substantial part of them are senior clients using these

applications to help themselves to stay fit, monitor

their own health status or keep in contact with their

healthcare provider. In contrast to the growing use of

eHealth to support HA, knowledge about effective

technologies and interventions for HA is clearly

absent. Decision makers need evidence on effective

strategies that could be implemented in order to

maximize health and wellbeing of older adults.

2 OBJECTIVES

This systematic review intends to shed light on the

promise of eHealth interventions in promoting HA

among older adults. This project targets two main

objectives: 1) to identify and systematically summarize

the best available evidence on the effectiveness of

eHealth interventions on HA; 2) to explore how

specific eHealth interventions (age-friendly,

community intervention, public policies) and their

characteristics (e.g.: mode of implementation) may be

implemented to effectively impact HA.

3 METHODS

We are conducting a systematic review of the

literature based on the Cochrane Collaboration

methods (Higgins and Green, 2011).

3.1 Types of Participants

This review considers studies that include male and

female adults aged 50 or more (as 50 years is

generally set as the beginning of the young old age

(Swedish National Institute of Public Health, 2006),

living in the community or in institutional

arrangement (e.g. nursing home), and who were

offered any intervention using eHealth for HA.

Exclusion criteria: 1) People with a terminal illness;

hospitalized in-patients; 2) Older adults with severe

impaired cognition, as measured by the Mini Mental

State Examination(Folstein et al., 1975)

3.2 Types of Interventions

This review consists of studies that evaluate

interventions on HA as defined above, and delivered

through eHealth, including teleHealth and

telemedicine, remote monitoring, internet, mobile

smart phones, interactive digital games, electronic

information systems. The interventions may take place

at home, in a community health center or another

relevant setting. The interventions may be delivered

individually or in groups. The interventions may last

one or more sessions of various time frames. Exclusion

criteria: Interventions that include an important face-

to-face component; Interventions using conventional

telephone, television or radio; Interventions using

technologies without an interactive component;

Interventions targeting treatment, or prevention of

complications of health problems.

3.3 Types of Outcomes

This review considers studies that include one or

A Systematic Review of eHealth Interventions for Healthy Aging: Status of Progress

123

more of the following outcome measures as defined

by the “Outcomes of interest to the Cochrane

consumers & communication review group”

(Cochrane Consumers in Communication Review

Group, 2012). Primary outcomes include: wellbeing,

quality of life, activities of daily living, leisure

activities, biological measures, health-enhancing

lifestyle, self-efficacy, and other related outcomes.

Secondary outcomes include: 1) knowledge and

understanding; 2) Participant decision-making

including decision made and satisfaction with

decision taken; 3) Evaluation of care including goal

attainment; 4) social support; 5) skills acquisition 6)

health behavior including adherence to treatment and

screening; and 7) other relevant outcomes. This study

will also consider adverse effects related to eHealth

interventions on HA in the targeted population.

Adverse effects may include: social isolation,

anxiety, burden on informal caregivers.

3.4 Types of Studies

The review includes any experimental study design

including randomized controlled trials, non-

randomized controlled trials; and quasi-experimental,

before and after studies for inclusion.

Studies published from 2000 up to 2015 in

English, Dutch, French or Spanish are considered for

inclusion.

3.5 Search Strategy

The search strategy aims to find both published and

unpublished studies. A three-step search strategy was

used. An initial exploratory search of Medline and

CINAHL was undertaken followed by an analysis of

the words contained in the title and abstracts, and of

the keywords and index terms used to describe

articles. A second search using all identified

keywords and index terms was then undertaken

across all included databases. Thirdly, after removing

duplicates from the reference manager Endnote, 7039

reference were obtained and are under the first round

of screening to map out those fitting the inclusion

criteria. Further, references list of included studies

will be screened for additional studies.

A final search is planned once ready to draft the

manuscript to identify any new relevant studies on the

topic. The search strategy (table 1) was adapted and

conducted in the following databases: CINAHL,

Cochrane Library, Embase, Eric, Campbell

Collaboration Library, PsycINFO, Web of Science,

and Social Work Abstracts.

3.6 Assessment of Methodological

Quality

Studies selected for retrieval were assessed by two

independent reviewers (IB & PV) for methodological

quality prior to inclusion in the review using the

Cochrane Risk of Bias tool (Higgins and Green,

2011). The disagreements that arose between the

reviewers were resolved through discussion with a

third reviewer (MPG or RB).

3.7 Data Extraction

Data will be extracted from studies included in the

review using a standardized data extraction tool based

on our previous reviews. The data extracted will

include specific details about the interventions,

populations, study methods and outcomes of

significance to the review question and specific

objectives. If needed, we will contact authors of

primary studies for missing information or to clarify

unclear data.

3.8 Data Synthesis

Where possible, data will be pooled in statistical

meta-analysis. Effect sizes expressed as odds ratio

(for categorical data) and weighted mean differences

(for continuous data) and their 95% confidence

intervals will be calculated for analysis.

Heterogeneity will be assessed statistically using the

standard Chi-square and also explored using

subgroup analyses based on the different study

designs included in the review. If statistical pooling is

not possible, we will present the findings in a

narrative form. We will undertake a qualitative

analysis of the descriptions of the interventions, as

provided in each report, to detail the interventions

components, inspired from the taxonomy of

interventions developed by EPOC (Effective Practice

and Organisation of Care (EPOC), 2015).

4 RESULTS

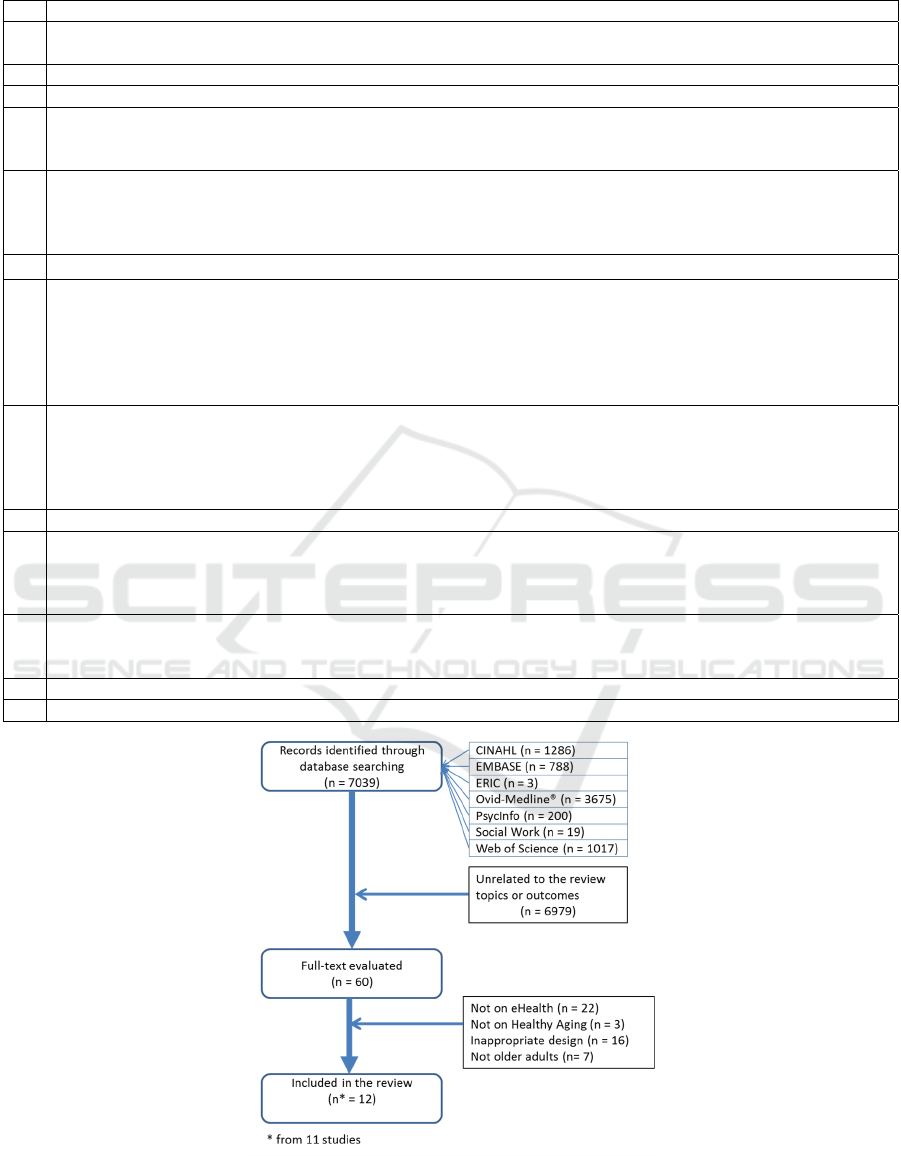

Figure 1 presents the flow diagram of the systematic

review. We have already conducted initial searches in

bibliographic databases and retrieved 7039 citations.

After initial screening of titles and abstracts, 60

publications were kept for further evaluation. The

study selection led to a final sample of 12 publications

describing 11 studies (see figure 1). Data extraction

from selected studies will be done from February to

ICT4AWE 2016 - 2nd International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

124

Table 1: Search strategy used in OVID-Medline ®.

No Concept equations

1 ("active ageing" or "active aging" or "Healthy ageing" or "Healthy aging" or Aging or "Middle Aged" or Aging or

Ageing or old or elder* or senior).ab,ti.

2 Middle Aged.mp. or exp Middle Aged/ or exp Aging/ or exp Aged/

3 1 or 2

4 (Project or program or Support or programme or intervention or "Health Education" or "Health Promotion" or

"Occupational Health Services" or "Health Services for the Aged" or "Preventive Health Care" or "Primary

Prevention").ab,ti.

5 Health Education.mp. or exp Health Education/ or Health Promotion.mp. or exp Health Promotion/ or

Occupational Health Services.mp. or exp Occupational Health Services/ or Health Services for the Aged.mp. or

exp Health Services for the Aged/ or Primary Prevention.mp. or exp Primary Prevention/ or Occupational Health

Nursing.mp. or exp Occupational Health Nursing/

6 4 or5

7 ("Health Communication" or Telenursing or Tele-nursing or "Health Informatics" or "Information Technology" or

"Information Technology Personnel" or internet or "World Wide Web" or Smartphone or online or on-line or web-

based or "web based" or webbased or "remote monitor*" or "interactive digital game" or "electronic information

system" or "Computer-Assisted" or "Computerized Health Record" or Telemedicine or Tele-medicine or

TeleHealth or TeleHealth or "Mobile health" or "Remote Consultation" or "Electronic Health Records" or "Public

Health Informatics" or "personal digital assistant").ab,ti.

8 Health Communication.mp. or exp Health Communication/ or exp Remote Consultation/ or Telenursing.mp. or

exp Telemedicine/ or exp Telenursing/ or exp Internet/ or exp Medical Informatics/ or Information

Technology.mp. or Information Technology Personnel.mp. or smartphone.mp. or exp Cell Phones/ or exp

Electronic Health Records/ or Computerized Health Record.mp. or TeleHealth.mp. or Public Health

Informatics.mp. or exp Public Health Informatics/

9 7 or 8

10 Health Education.mp. or exp Health Education/ or exp Health Behavior/ or exp Health Knowledge, Attitudes,

Practice/ or Health Knowledge.mp. or Quality of Life.mp. or exp "Quality of Life"/ or Self Efficacy.mp. or exp

Self Efficacy/ or Social Support.mp. or exp Social Support/ or Life Style.mp. or exp Life Style/ or Health

Literacy.mp. or exp Health Literacy/ or Risk Reduction Behavior.mp. or exp Risk Reduction Behavior/

11 ("Health Knowledge" or "Health Behavior" or "Quality of Life" or "Self-Efficacy" or "Social Support" or "Life

Style" or "health education" or "health knowledge attitude and practice" or "health Attitude" or "Health Literacy"

or "Health Behaviour" or "Quality of Life" or "psychco-Social Support" or "Risk Reduction Behavior").ab,ti.

12 10 or 11

3 and 6 and 9 and 12

Figure 1: Study selection and flow diagram.

A Systematic Review of eHealth Interventions for Healthy Aging: Status of Progress

125

March 2016, and data synthesis will be completed in

May 2016.

5 CONCLUSIONS

Aging population is a worldwide topical issue and

eHealth a promising resource to address this raising

challenge. This review, first of its kind, will shed light

on eHealth as promising resource to support HA. The

findings from this systematic review stemmed from

salient eHealth interventions implemented will

engender insight regarding the role of eHealth to

answer the increasing needs of an aging population.

The findings will offer possible alternatives for better

policy making option for HA.

REFERENCES

Brownsell, S & Hawley M.S. 2004. Automatic fall

detectors and the fear of falling. Journal of

Telemedicine and Telecare, 10, 262-266.

Cochrane consumers in communication review group 2012.

Outcomes of Interest to the Cochrane Consumers &

Communication Review Group 2012.

Cook, R. F., Hersch, R. K., Schlossberg, D. & Leaf, S. L.

2015. A Web-based health promotion program for older

workers: randomized controlled trial. Journal of

medical Internet research, 17.

Effective practice and organisation of care (EPOC) 2015.

Suggested risk of bias criteria for EPOC reviews. EPOC

Resources for review authors. Oslo: Norwegian

Knowledge Centre for the Health Services,.

Folstein, M., Folstein, S. & Mchugh, P. 1975. Mini-mental

state : a practical method for grading the cognitive state

of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res, 12, 189-

198.

Hall, A. K., Stellefson, M. & Bernhardt, J. M. 2012.

Healthy Aging 2.0: The Potential of New Media and

Technology. Preventing Chronic Disease.

Hansen-Kyle, L. 2005. A Concept Analysis of Healthy

Aging. Nursing Forum, 40, 45-57.

Heinbuchner, B., Hautzinger, M., Becker, C. & Pfeiffer, K.

2010. Satisfaction and use of personal emergency

response systems. Z Gerontol Geriatr, 43, 219-23.

Henriquez-Camacho, C., Losa, J., MirandA, J. J. & Cheyne,

N. E. 2014. Addressing healthy aging populations in

developing countries: unlocking the opportunity of

eHealth and mHealth. Emerg Themes Epidemiol, 11,

136.

Higgins, J. & Green, S. 2011. Cochrane handbook for

systematic reviews of interventions Version 5.1. 0

[updated March 2011].

Hofäcker, D. 2014. In line or at odds with active ageing

policies? Exploring patterns of retirement preferences

in Europe. Ageing and Society, 35, 1529-1556.

Hofäcker, D. & Naumann, E. 2015. The emerging trend of

work beyond retirement age in Germany. Increasing

social inequality? Z Gerontol Geriatr, 48, 473-9.

Illario, M., Vollenbroek-Hutten, M., Molloy, D. W.,

Menditto, E., Iaccarino, G. & Eklund, P. 2015. Active

and Healthy Ageing and Independent Living. J Aging

Res, 2015, 542183.

Jin, K., Simpkins, J. W., Ji, X., Leis, M. & Stambler, I.

2015. The Critical Need to Promote Research of Aging

and Aging-related Diseases to Improve Health and

Longevity of the Elderly Population. Aging Dis, 6,

1-5.

Kinsella, K. & Phillips, D. 2005. Global Aging: The

Challenge of Success. Population Reference Bureau,

Washington DC,.

Lattanzio, F., Abbatecola, A. M., Bevilacqua, R., Chiatti,

C., Corsonello, A., Rossi, L., Bustacchini, S. &

Bernabei, R. 2014. Advanced technology care

innovation for older people in Italy: necessity and

opportunity to promote health and wellbeing. J Am Med

Dir Assoc, 15, 457-66.

LondeI, S. T., Rousseau, J., Ducharme, F., St-Arnaud, A.,

Meunier, J., Saint-Arnaud, J. & Giroux, F. 2009. An

intelligent videomonitoring system for fall detection at

home: perceptions of elderly people. J Telemed

Telecare, 15, 383-90.

Mihailidis, A., Cockburn, A., Longley, C. & Boger, J. 2008.

The acceptability of home monitoring technology

among community-dwelling older adults and baby

boomers. Assist Technol, 20, 1-12.

Pew Research Center 2014. Older Adults and Technology

Use.

Rébola, C. B. 2015. Designed Tecnologies for Healthy

Aging, Morgan & Claypool Publishers.

Reis, A., Pedrosa, A., Dourado, M. & Reis, C. 2013.

Information and Communication Technologies in

Long-term and Palliative Care. Procedia Technology,

9, 1303-1312.

Research2guidance 2014. mHealth App Developer

Economics 2014 The State of the Art of mHealth App

Publishing.

Rosella, L. C., Fitzpatrick, T., Wodchis, W. P., Calzavara,

A., Manson, H. & Goel, V. 2014. High-cost health care

users in Ontario, Canada- demographic, socio-

economic, and health status characteristics. BMC

Health Services Research 14, 1-13.

Silveira, P., Van Het Reve, E., Daniel, F., Casati, F. & De

Bruin, E. D. 2013. Motivating and assisting physical

exercise in independently living older adults: a pilot

study. Int J Med Inform, 82, 325-34.

Swedish National Institute of Public Health 2006. Healthy

aging: a challenge for Europe. Stockholm.

Willner V, Schneider C, Feichtenschlager M. 2015. eHealth

2015 Special Issue: Effects of an Assistance Service on

the Quality of Life of Elderly Users. Appl Clin Inform,

6, 429-42.

World Health Organization 2002. Active Ageing: A Policy

Framework. Geneva.

Wu, G. & Keyes, L. M. 2006. Group Tele-Exercise for

Improving Balance in Elders. Telemedicine and

eHealth, 12, 562-571.

ICT4AWE 2016 - 2nd International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

126