Using Blended Learning to Support Community Development -

Lessons Learnt from a Platform for Accessibility Experts

Christophe Ponsard

1

, Jo

¨

el Chouassi

2

, Vincent Snoeck

3

, Anne-Sophie Marchal

3

and Julie Vanhalewyn

4

1

CETIC Research Centre, Gosselies, Belgium

2

HEPH Condorcet High School, Mons, Belgium

3

GAMAH asbl, Namur, Belgium

4

Plain-Pied asbl, Namur, Belgium

Keywords:

E-learning, Blended Learning, Knowledge Sharing, Collaborative Learning, Community Building, Accessi-

bility.

Abstract:

Blended learning, mixing both online and face-to-face learning, is now a well established trend in higher

education and also increasingly used in companies and public sector. While preserving direct contact with

the teacher/trainer, it also provides additional electronic channels to easily share training material and to sup-

port interactions among all actors. This paper focuses on specificities of adult training such as their goal-

orientation, the higher level of practicality and the higher level of collaboration. We also deal with the explicit

goal of building communities where learners are progressively sharing their growing experience. Our work is

driven by a real-world case study. We report about how generic e-learning tools available on the market can

be adapted to address the needs of such a use case and also present some lessons learnt.

1 INTRODUCTION

E-learning can be broadly defined as the use of Inter-

net technologies to deliver a large array of solutions

that enhance knowledge and performance (Rosen-

berg, 2001). It covers a wide range of tools enabling

to access online teaching material under written, au-

dio and video formats. It also provides new commu-

nication channels among and between learners, teach-

ers and tutors, such as forums and instant messaging.

Blended (or hybrid) learning covers the wide mixed

spectrum of teaching and learning styles between the

traditional face-to-face teaching in classrooms and the

pure online course (Stein and Graham, 2014).

E-learning developed originally in universities

and higher schools thanks the combination of need,

technological readiness and Internet connectivity.

With the extension of Internet and more recently the

mobile connectivity, it has reached adults inside com-

panies and public sector. A recent survey has reported

than more than 40% of the biggest companies use

some form of technology to instruct their employees

(eLearning Infographics, 2013). The learning adult

has a number of known specificities, as reported in

the literature (Knowles, 1984). The main differentia-

tors are a greater level of autonomy, the use of its life

experience, the need to have clear goals and that such

goals make sense while having a practical orientation.

Moreover, adult learners like to build collaborative re-

lationships with their educators.

This paper considers the case of collaborative

learning with the explicit goal of building a commu-

nity of expert in a specific domain while taking into

account the accessibility of public places. This re-

quires face-to-face learning and field practice, but can

also benefit from online tools. This work combines

both blended learning and community building as-

pects. We report about how we designed, built and

deployed an on-line platform addressing these needs.

This paper is structured in order to report our ex-

perience in a way that can benefit to others. Section 2

presents our case study by highlighting more general

requirements. Section 2 details and motivates our de-

sign choices. Section 3 describes how we iteratively

adapted and validated the suitability of a major Open

Source platform with respect to our needs. Section

4 reports about the lessons learnt and Section 5 dis-

cusses some related work. Finally, section 6 draws

conclusions and presents some further work.

Ponsard, C., Chouassi, J., Snoeck, V., Marchal, A-S. and Vanhalewyn, J.

Using Blended Learning to Support Community Development - Lessons Learnt from a Platform for Accessibility Experts.

In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2016) - Volume 2, pages 359-364

ISBN: 978-989-758-179-3

Copyright

c

2016 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

359

2 CASE STUDY AND

GENERALISATION

This section presents our case study and identifies

general requirements for systems aiming at achieving

learning and building communities. A number of key

driving properties are also highlighted in bold case.

In Belgium, as in many countries, the level of

physical accessibility of buildings open to public is

generally poor, thus hindering the access to people

with reduced mobility. Assessing the accessibility of

buildings requires a specific expertise only developed

by few associations (Ponsard and Snoeck, 2006). The

total available expertise does not allow to deal with

with huge amounts of places. This leaves the associ-

ations with two options: either (i) conduct a few tar-

geted assessments with a high level of quality, or (ii)

rely on a large number of people with only basic skills

to conduct low quality assessments, and use the effect

of mass (crowd-sourcing) (Prandi et al., 2014).

Neither option is really satisfactory but introduc-

ing the training and community building dimension

can bridge the gap as there is a large reservoir of

people willing to grow their expertise and possibly

get a job in the area. Another aspect is that there is

also a progressive learning curve: starting from ba-

sic assessments to more complex ones, then issuing

indicative and finally authoritative recommendations.

Another characteristics is that the domain of exper-

tise is quite sharp, as consequence physical train-

ing sessions are not very frequent and only organized

at specific times (twice a year) and places. In order

to optimize the time spent in physical course, it is

important to have a maximum of support for on-line

learning. Finally, the application domain itself is

increasingly relying on IT tools for conducting as-

sessment (use of digital cameras, tablets, GPS, etc).

In order to support the on-line learning, the fol-

lowing requirements were collected. On the func-

tional side, it should:

• FR1 - support different courses and dependencies

• FR2 - support different types of training materials

(text, audio, video...)

• FR3 - provide communication channels such as

blogs, forums, chats, off-line messages.

The following non-functional requirement were

also identified. The system should be:

• NFR1 - web-based, i.e. run in a standard browser

without requiring any installation in the trainee

side

• NFR2 - providing a simple user interface for the

trainee

• NFR3 - relying solely on Open-Source compo-

nents

• NFR4 - secured (authentication, access control

enforcement, privacy)

• NFR5 - compliant with e-accessibility standards,

like WCAG (Reid and Snow-Weaver, 2008)

The last requirements is especially important

given the domain, but should not be neglected any-

way in all learning solutions.

3 ITERATIVE DESIGN,

DEVELOPMENT AND

VALIDATION OF THE IT

PLATFORM

In order to produce an adequate IT platform, an Ag-

ile process was conducted in preparation of a new

training session (Moran, 2015). The platform design,

development and validation was conducted in three

sprints (agile iterations), each lasting one month. It

involved the following profiles:

• domain experts (trainers of previous sessions)

• trainees selected from previous sessions based on

their results and motivation

• an IT architect with some experience in e-learning

software

• a web developer and system administrator

• an (external) e-accessibility expert from the Any-

Surfer association (AnySurfer, 2000)

The first sprint was devoted to the problem anal-

ysis (i.e. requirements of previous section), the re-

view of available technologies and the production

of a solution design. A specific workshop devoted

to the design yielded the idea to structure the design

around the familiar terms borrowed to the school and

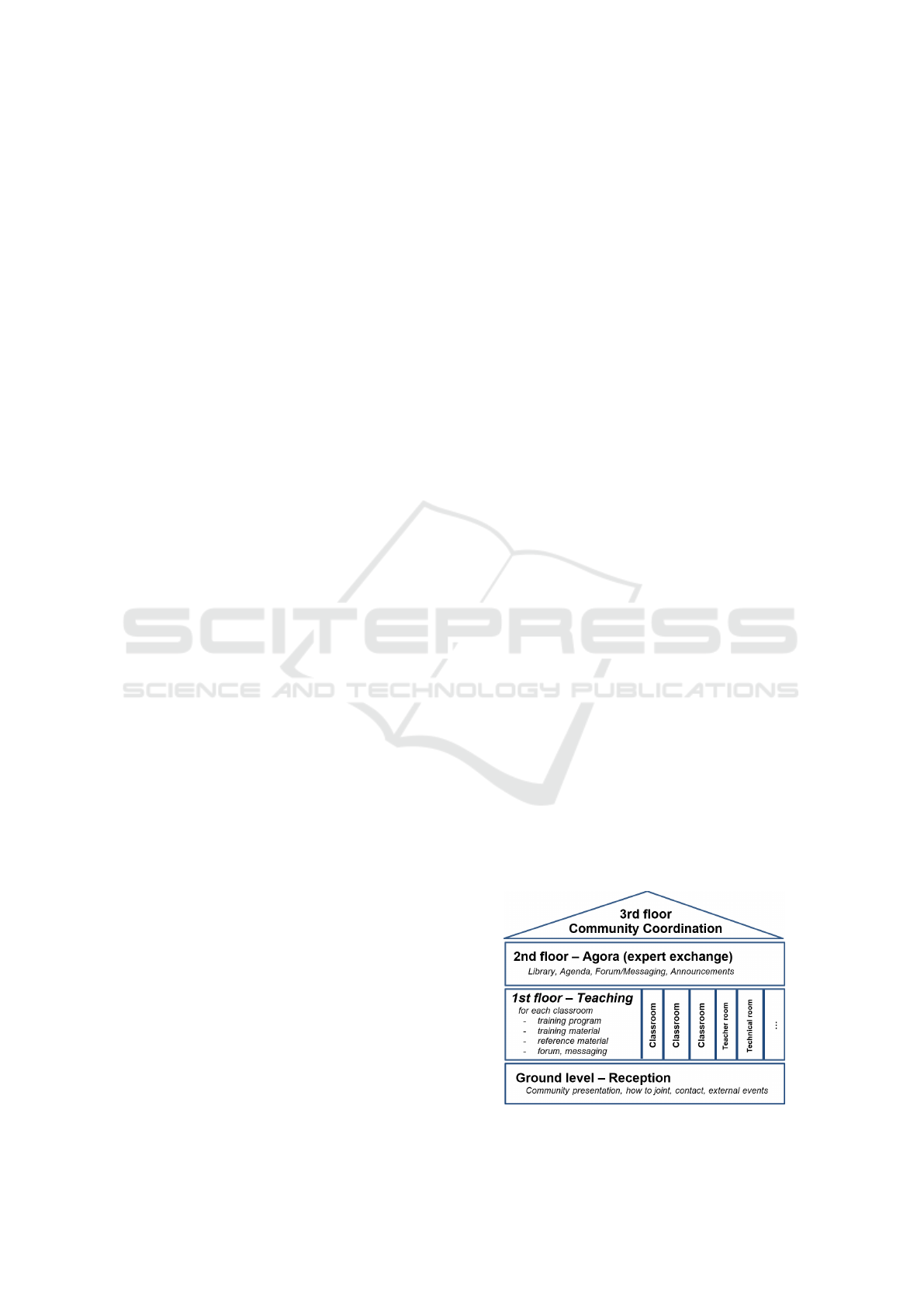

Figure 1: School Metaphor.

CSEDU 2016 - 8th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

360

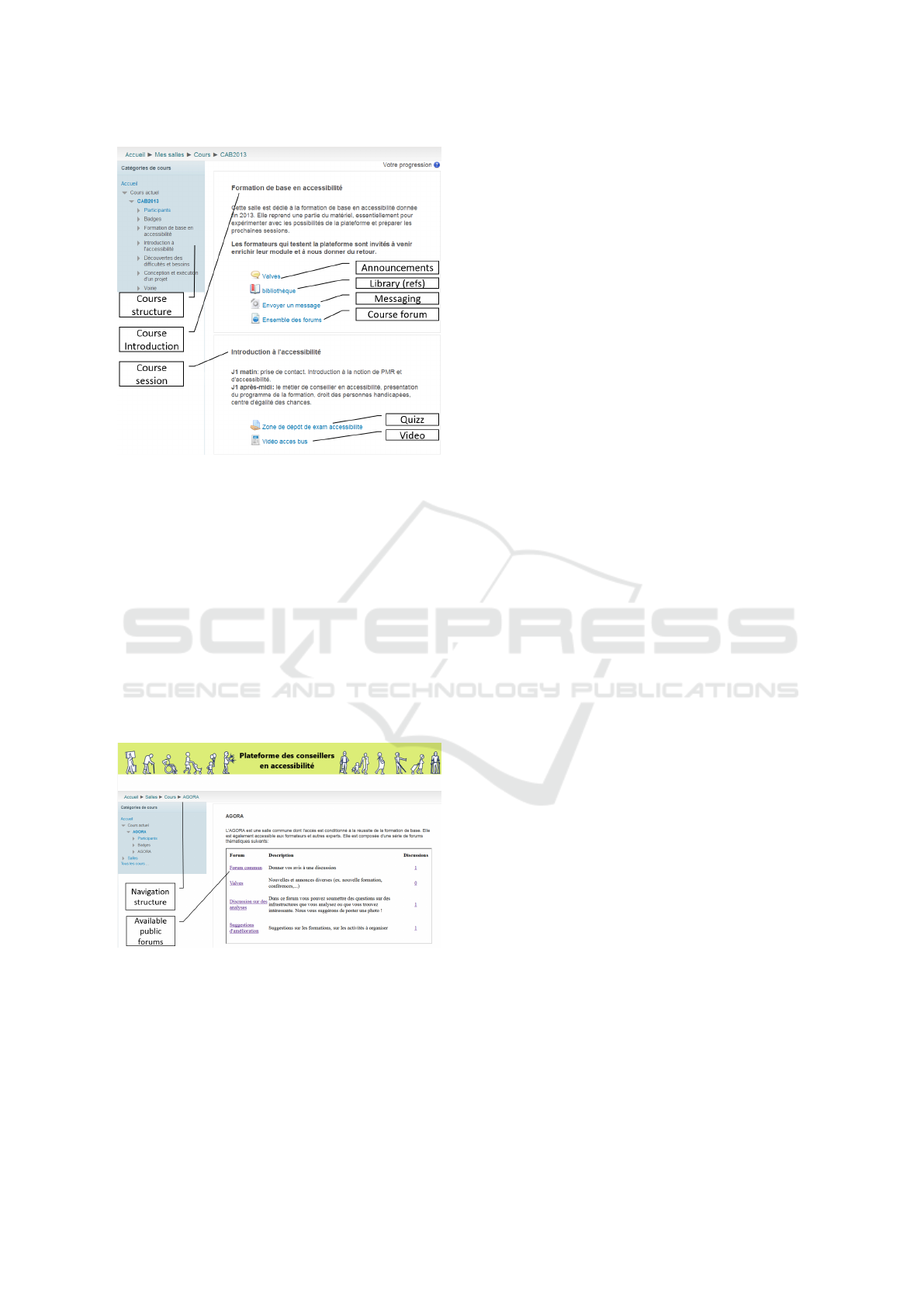

Figure 2: Homepage.

library terminologies (e.g. classroom, machine room,

agora,...). It also introduced the metaphor of a build-

ing with different floors corresponding to the different

levels of expertise acquired, as depicted in Figure 1.

• the ground floor is the public floor. It is accessible

to everybody (i.e. no specific credentials required

to view the page content). It provides general pub-

lic information and, more importantly, informa-

tion specifically targeting potential new learners

on how to join, the planning and organization of

future sessions, etc.

• the first floor corresponds to the training sessions

organized (so far only a basic level and a second

(more advanced) level). It is accessible upon ac-

cepted registration based on a few prerequisites.

Each classroom has a similar structure with an

agenda of the planned physical lectures, some ma-

terial (course, preparation, follow-up exercises),

addition specific references and a specific forum.

Additional rooms are available, such as a teacher

room to ease the sharing of material when prepar-

ing a new course or new sessions of an existing

course.

• the second floor is accessible upon the comple-

tion of at least the basic course. It corresponds

to the community level of the platform. People

can share their opinion on different cases that are

made available through a repository. The level of

expertise is made visible in the interaction.

• the third and last floor is reserved to the platform

coordinator and is dedicated to the platform man-

agement activities, including registering students,

enrolling them, creating new ”classrooms”, as-

signing teachers, announcing events, etc.

During this phase, a comparative analysis of dif-

ferent Learning Management Systems (LMS) plat-

forms such Moodle (Dougiamas, 2002) and Claro-

line (UCL/IPM, 2000) were also conducted. Some

demonstration of the raw possibilities of the platform

were organized.

The second sprint was devoted to build a first pro-

totype by focusing on functional requirements and

supporting a simple set of users stories, mostly

focused on the learner. The selected platform was

Moodle, as it ranked better at covering the required

features and also because of its large community, rich

support and substantial plugin ecosystem. It was de-

ployed on a LAMP (Linux-Apache-Mysql-PHP) con-

figuration based on an Ubuntu virtual machine hosted

by the IT project partner. As the initial performance

was poor, a PHP opcache was used and the RAM size

was increased.

Figure 2 illustrates the resulting homepage while

Figure 3 shows the structure of a course as it was con-

figured. The navigation structure shows the structure

of the course, composed of a number of modules. The

central part shows the details. The first section con-

tains the course introduction and common tools such

as the agenda, references, messaging and forums. It

is followed by the module details and its own specific

content.

At the end of this session, a validation was con-

ducted with selected trainees. It resulted in the iden-

tification of a number of potential improvements to

carry out in the next phase. At that point, a major is-

sue in terms of usability emerged as the default layout

of the Moodle platform was felt far too complex (see

lessons learnt).

The third sprint was devoted to improving the pro-

totype in order to support more user stories and

Using Blended Learning to Support Community Development - Lessons Learnt from a Platform for Accessibility Experts

361

Figure 3: Course structure.

non-functional requirements. The considered user

stories focused on the work of the teachers (lecture

design, message classes, etc) and platform managers

(registrations, announcements, etc). A large effort

was devoted to usability improvements (see lessons

learnt). Most of the effort focused on configuration

tuning and the specific development of an improved

forum presentation module. Figure 4 shows the Agora

level with simplified layout and the custom forum

module. As the management level functions are only

used by a few people, the standard Moodle functions

were kept. We just added some integration with a reg-

istration form managed through a Google form.

Figure 4: Agora module.

At the end of this sprint, a complete validation ses-

sion was conducted. A complete schedule of the next

planned session was encoded, the first two lectures

were encoded and a complete rehearsal was organized

with former students. The final feedback was very

positive, as the users truly felt that the new simplified

interface was clearer and easier to use.

4 LESSONS LEARNT

Beyond achieving the success of a training pro-

gramme, our goal is also to build a long term com-

munity. We identified the following lessons and for-

mulate them in more general terms.

Have all community stakeholders on board. For

this using an Agile approach mixing different plat-

form stakeholders proved very effective. The level of

commitment was high and all the validation could be

conducted within the agreed schedule despite the high

load of many partners. The sprint period could even

be shorter provided more resources are allocated. We

could rely on the following key parties:

• a network of experts (CAWAB association of ac-

cessibility expert in our case). The existence of

such a network is an important success factor. The

project itself also contributed to reinforce it.

• trainees issued from previous training pro-

grammes: although there was some form of

”keeping in touch” by newsletters, emails, social-

network groups, or specific forms of collabora-

tion, a collaborative platform was definitely miss-

ing. Previously trained people where very keen to

volunteer to get involved in the design and valida-

tion process of the platform and were very effec-

tive at giving high quality feedback. Such people

also greatly help in sow more seeds to grow the

community thanks to their own contacts.

Platform usability is a key point. On the techni-

cal level, the Moodle platform provided all the re-

quired features either natively or as plugins. Only

a few functional adaptations were necessary to com-

plete the functional scope: a contact form and better

module to structure forums. However the first vali-

dation revealed that many unnecessary features were

exposed and resulted in a strong degradation of the

user experience. Improving usability was identified

as a key point to avoid rejection. So an important

lesson learned was to avoid feature creep and use

the KISS (Keep It Simple, Stupid) principle (Ray-

mond and Steele, 1991). So, an important effort was

devoted to simplify the user interface by switching to

another template and deactivating a number of useless

features. Actually some adaptations proved not trivial

at all to achieve with Moodle and the effort devoted

to this step should not be underestimated. In our case

it can be estimated to one third of the development

effort.

Adapt to the community specificities. As the do-

main is accessibility, we can expect also mobility

CSEDU 2016 - 8th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

362

impaired people to get involved as expert, thus e-

Accessibility was an absolute requirement in our

case. Unfortunately, this specific requirement of e-

Accessibility could only be partially be achieved al-

though the Belgian AnySurfer association provided

some help (AnySurfer, 2000). The main barrier was

the lack of accessibility to blind users of specific

forms directly managed by Moodle. The only pos-

sible action was to report this to the Moodle commu-

nity. Although this requirement was identified, the

ease of adaptation was not well validated enough at

design time and might have impacted the choice to an-

other platform. Other communities might have other

requirements, for example for multilingual support.

Actually in our case, as some trainees are not fluent in

French, a specific form of support is being studied.

5 RELATED WORK AND

DISCUSSION

Structuring the platform based on the familiar school

metaphor has been quite common since the early

years of e-learning. It was however criticized for its

pedagogical limits, trying to adhere too much to its

physical model (Carliner and Shank, 2008). The sit-

uation nowadays is however different because most

people have a extensive experience of the web and

social media tools. There is therefore little chance of

people just behaving like in the real world. More-

over, our use of this metaphor is not generalized and

social communication channels are kept with their

usual names. In our implementation of the concept,

we were more interested in the remembrance that the

terms would evoke, rather than implementing a virtual

classroom experience like in (Barab et al., 2001).

A complete vision and roadmap to understand

what can be done by blending face-to-face and online

learning in order to produce engaging and meaning-

ful learning experiences is reported in (Kitchenham,

2011). It describes a number of scenarios, guide-

lines, strategies and tools. This book however fo-

cuses on higher education, whereas our focus is rather

community-driven than academic.

Expertise networks in on-line communities have

been extensively studied. Automatic expertise rank-

ing algorithms are available and commonly used in

help forums (Noll et al., 2009). In our case, we rely on

a blended learning with a mix of on-line and physical

interactions, there is no needs for automatic assess-

ment. First, only people with a basic training level can

access the Agora level. Second, the expertise level is

assessed by the training outcome. It results in the the

production of ”badges” that are displayed in people

on-line profile. Third, people also have the opportu-

nity to meet physically and learn to know each other.

Nevertheless, it remains interesting to analyse the dy-

namics of the interaction on our forums, for exam-

ple using tools like (Zhang et al., 2007), especially in

the perspective of a direct channel with infrastructure

owners.

Guidelines for achieving the best mix of on-line

and face-to-face learning are proposed in (Garrison

and Vaughan, 2011). It provides a detailed roadmap

for achieving an effective and efficient blended learn-

ing environments at different stages (design, instruc-

tion, assessment). Our work relies on similar princi-

ples and design decision were generally easy to take

because a number of assessment activities have to

be carried out in the physical world. Transforming

some activities in electronic activities like conducting

photo-based assessment actually also makes sense be-

cause assessors only spend a few hours on-site and

then the work is finalised off-site. Sometimes it also

involves people that did not visit the infrastructure.

6 CONCLUSION AND

PERSPECTIVES

In this paper, we have shown how to address the needs

for a platform supporting both blended e-learning and

community building for accessibility experts. In order

to share our experience in the most reusable form, we

used generic terms to report our work across the dif-

ferent conducted phases of requirements, design, de-

velopment and validation. We also identified interest-

ing lessons learnt to help other e-learning managers

or community builders that face similar needs. Our

prototype is available online at http://cena.accessible-

it.org (Chouassi and Ponsard, 2015).

Our future work includes the continuous improve-

ment of the platform based on the upcoming training

sessions, the management of evolving training mate-

rial through time and the organization of more spe-

cific material for the second level of training, the lat-

ter being organized in smaller groups (for instance

reduced to pairs of expert/trainee conducting stan-

dard assessments). The development of a specific

picture annotation tool, in order to comment on the

accessibility of pictures gathered by experts, is also

planned since such a specific tool will undeniably

bring greater added value to the platform in terms of

knowledge sharing. Finally, opening a direct channel

where infrastructure owners can report and get advice

about their accessibility problems is also being con-

sidered.

Using Blended Learning to Support Community Development - Lessons Learnt from a Platform for Accessibility Experts

363

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This work was financially supported by the Walloon

Region by the IDEES CO-INNOVATION project. We

thanks the CAWAB, the Walloon network of acces-

sibility associations (especially GAMAH and Plain-

Pied) for their strong involvement in the Agile process

that led to the creation of the CENA platform.

REFERENCES

AnySurfer (2000). Towards an accessible internet.

http://www.anysurfer.be/en.

Barab, S., MaKinster, J., Moore, J., and Cunningham, D.

(2001). Designing and building an on-line commu-

nity: The struggle to support sociability in the inquiry

learning forum. Educational Technology Research

and Development, 49(4):71–96.

Carliner, S. and Shank, P. (2008). The e-Learning Hand-

book: Past Promises, Present Challenges. Pfeiffer

essential resources for training and HR professionals.

Wiley.

Chouassi, J. and Ponsard, C. (2015). CENA on-

line platform for accessibility experts (in French).

http://cena.accessible-it.org.

Dougiamas, M. (2002). Moodle - Open-Source Software

Learning Management System. https://moodle.org.

eLearning Infographics (2013). Top 10

eLearning Statistics for 2014 Infographic.

http://elearninginfographics.com/elearning-statistics-

2014-infographic.

Garrison, D. and Vaughan, N. (2011). Blended Learn-

ing in Higher Education: Framework, Principles, and

Guidelines. Jossey-Bass higher and adult education

series. Wiley.

Kitchenham, A. (2011). Blended Learning across Disci-

plines: Models for Implementation: Models for Im-

plementation. Information Science Reference.

Knowles, M. S. (1984). The Adult Learner : a Neglected

Species. Gulf Pub. Co., Book Division.

Moran, A. (2015). Managing Agile: Strategy, Implemen-

tation, Organisation and People. Springer Publishing

Company, Incorporated.

Noll, M. G., Au Yeung, C.-m., Gibbins, N., Meinel, C.,

and Shadbolt, N. (2009). Telling experts from spam-

mers: Expertise ranking in folksonomies. In Pro-

ceedings of the 32Nd International ACM SIGIR Con-

ference on Research and Development in Information

Retrieval, SIGIR ’09, pages 612–619, New York, NY,

USA. ACM.

Ponsard, C. and Snoeck, V. (2006). Objective accessibil-

ity assessment of public infrastructures. In Computers

Helping People with Special Needs, 10th International

Conference, ICCHP 2006, Linz, Austria, July 11-13,

2006, Proceedings, pages 314–321.

Prandi, C., Mirri, S., and Salomoni, P. (2014). Trustwor-

thiness assessment in mapping urban accessibility via

sensing and crowdsourcing. In The First International

Conference on IoT in Urban Space, Urb-IoT 2014,

Rome, Italy, October 27-28, 2014, pages 108–110.

Raymond, E. and Steele, G. (1991). The New Hacker’s Dic-

tionary. MIT Press.

Reid, L. G. and Snow-Weaver, A. (2008). Wcag 2.0: A web

accessibility standard for the evolving web. In Proc.

of the 2008 International Cross-disciplinary Confer-

ence on Web Accessibility (W4A), W4A ’08, pages

109–115, New York, NY, USA. ACM.

Rosenberg, M. J. (2001). E-Learning: Strategies for De-

livering Knowledge in the Digital Age. McGraw-Hill,

Inc., New York, NY, USA.

Stein, J. and Graham, C. (2014). Essentials for Blended

Learning: A Standards-Based Guide. Essentials of

Online Learning. Taylor & Francis.

UCL/IPM (2000). Claroline Connect.

http://www.claroline.net.

Zhang, J., Ackerman, M. S., and Adamic, L. (2007). Ex-

pertise networks in online communities: Structure and

algorithms. In Proceedings of the 16th International

Conference on World Wide Web, WWW ’07, pages

221–230, New York, NY, USA. ACM.

CSEDU 2016 - 8th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

364