Weaving Business Model Patterns

Understanding Business Models

Mar

´

ıa Camila Romero, Mario S

´

anchez and Jorge Villalobos

Systems and Computing Engineering, Universidad de los Andes, Bogot

´

a, Colombia

Keywords:

Business Model, Structural View, Behavioral View, Business Model Pattern.

Abstract:

A business model describes the way in which an organization acquires raw materials, transforms them into a

product or service that is delivered to a client, and gains money in exchange. In consequence, it is possible to

decompose the model into four core processes: supply, transformation, delivery, and monetization, which have

both structural and behavioral dependencies among them. Unfortunately, most business model representations

focus only on the structural part and leave aside the interactions between said processes. The objective of this

paper is twofold. Firstly, it presents a conceptualization and representation for business models that is capable

of handling their components and interactions. Secondly, it uses the proposed representation to introduce a

catalog of business patterns applicable in the design and analysis of business models. Each pattern includes

the basic participants, resources, activities and interactions that must be accounted for in order to perform the

core process.

1 INTRODUCTION

Business models describe the way in which an or-

ganization transforms, delivers and monetizes value.

Though this definition is quite simple, it has led to

different interpretations and consequently, a great

variety of models that try to embrace the concept.

However, this broad selection of models has also

contributed to a lack of formality in the idea itself

(Lindgren and Rasmussen, 2013). It is no longer

clear how business models are supposed to be used,

designed, or described. In addition to the scarcity of

standards, there is a dearth of means to define and

communicate business models, so that they can be

understood, analyzed, and improved upon.

With a precise definition of a business model,

small and medium enterprises (SME) could perceive

various benefits. Since their main concern is staying

afloat in the market, long term decisions are not part

of their priorities, leading to two possible outcomes:

either they grow and manage to position in the

market, or they fail, cease to exist (Frick and Ali,

2013) and stop contributing to the economic growth,

innovation and employment of their country (Robu,

2013).With a well defined business model, SMEs

would be able to recognize the different relationships

present in their business and plan ahead, in order to

execute a successful strategy.

The critical problem with current business model

representations is the focus on a structural dimen-

sion (e.g., Osterwalder’s Canvas (Osterwalder and

Pigneur, 2010), or Gordijns e3-value (Gordijn and

Akkermans, 2001). In particular, they leave (mostly)

aside the specification of how business models

components interact and behave in order to make the

model work. Therefore, only a partial understanding

of the business can be achieved with these business

models. Additional artifacts are thus required,

especially to achieve the goals behind Enterprise

Modeling and Enterprise Engineering efforts.

This paper proposes two contributions. Firstly,

it presents a conceptualization and representation of

business models that includes all of their elements

and allows further and more advanced analysis and

understanding. Secondly, it introduces a catalog of

business patterns which targets all the aspects of a

business model. These patterns are intended to be

the starting point for understanding and improving

business models, especially in small and medium

enterprises.

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 dis-

cusses the current understanding and representation

of business models. Then, Section 3 presents our pro-

posal for understanding business models by showing

all its elements and the way in which they can be

graphically represented. Next, the designed catalog

of business patterns is introduced, and a few selected

patterns are presented. Finally, related work is presented

496

Romero, M., Sánchez, M. and Villalobos, J.

Weaving Business Model Patterns - Understanding Business Models.

In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS 2016) - Volume 2, pages 496-505

ISBN: 978-989-758-187-8

Copyright

c

2016 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

in Section 5, and in Section 6 the paper is concluded

.

2 UNDERSTANDING BUSINESS

MODELS

A business is defined as a commercial activity in

which one engages in, in exchange for money. Re-

gardless of the product or service that is being ex-

changed, to produce the desired revenue every busi-

ness transforms, delivers, and monetizes value. The

way in which they do so, is known as a business

model.

Several attempts to define what a business model

is, have led to a diversity of interpretations. In turn,

the concept has become blurry and there are no formal

representations for it. This scenario explains the suc-

cess of tools such as Alexander Osterwalder’s Busi-

ness Model Canvas (Osterwalder and Pigneur, 2010).

The simple yet complete representation of the busi-

ness model, has been adopted worldwide for describ-

ing businesses. By identifying 9 key elements, a can-

vas is able to communicate how a business works on a

superficial level, and even propose alternative designs

in order to adjust the model in a changing environ-

ment. Thus, these 9 elements allow the description of

the business model, by defining its structural compo-

nents.

2.1 Core Processes

Supply

Transform

Monetize

Deliver

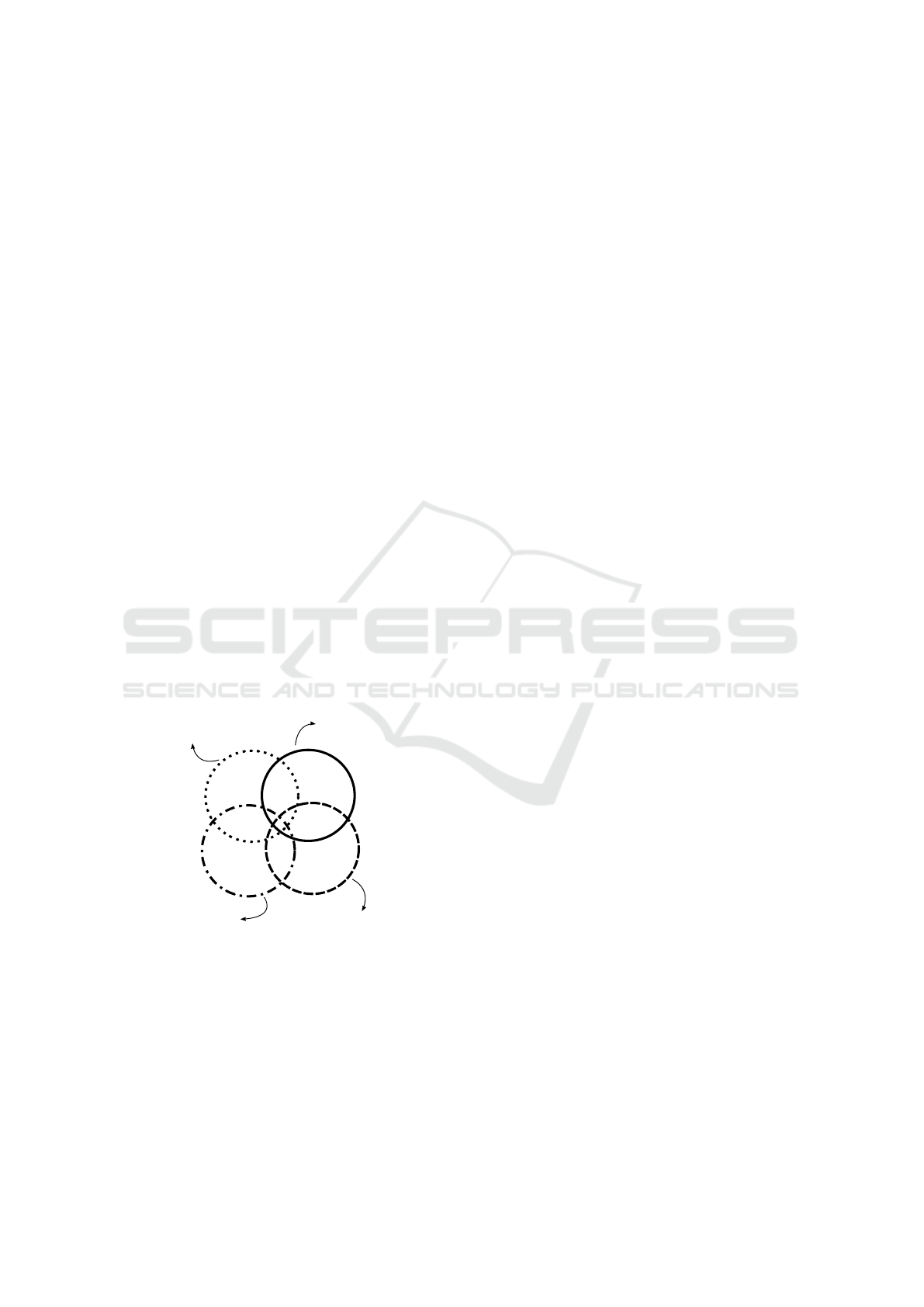

Figure 1: Business Model Processes.

Another perspective for understanding business

models is the way in which an organization acquires

supplies, transforms them into products and services,

delivers these products and services, and obtains some

money in exchange i.e., monetizes products and ser-

vices. Accordingly, a business model can be decom-

posed into the four processes shown in Figure 1: Sup-

ply, where the business performs all the activities nec-

essary to acquire raw materials; Transformation, in

which supplies are processed, typically adding value

to them, in order to obtain the desired good or ser-

vice; Delivery, that considers the distribution of the

product or service to the client, and all the activities

that lead to this delivery (e.g., marketing, customer

acquisition); and Monetization, where the business

performs the activities associated to the generation of

revenues.

The order in which these processes are performed

and the specific nature of their activities, varies de-

pending on the type of product or service offered.

Manufacturing businesses with a traditional model,

first acquire their raw materials (Supply) to trans-

form them (Transformation) and deliver the result-

ing products to the client (Delivery) which pays for

them (Monetization) and generate revenue. Other

businesses require a different sequence. For instance,

transformation and delivery may be performed simul-

taneously, if the product or service is transformed as

it is delivered. A business that exemplifies this se-

quence is private education: an educational service

that is provided, is transformed (adding value) as it

is being delivered and it is only at the end, when stu-

dents graduate, that the complete service that was paid

for is perceived.

2.2 Structural and Behavioral

Viewpoints

Business models comprise two aspects which can be

analyzed from two complementary points of view:

structural elements, which include the business model

components and their structural relations; and depen-

dencies and interactions between said components.

When business models are analyzed from the

structural viewpoint, the first elements to study are

their four main processes (Supply, Transform, De-

liver, and Monetize) and their relations. This includes

analyzing the participants in each one of these pro-

cesses and their responsibilities, as well as the activ-

ities that they have to perform. Special attention is

also paid to the resources required to perform the ac-

tivities, such as machines, communication and deliv-

ery channels, as well as financial resources. All these

resources and activities generate costs, which are con-

sidered part of the structural viewpoint as they are at-

tributes that shape the model. Well known representa-

tions, such as Osterwalder’s Canvas, or Gordijin’s e3-

value (Gordijn and Akkermans, 2001), are well suited

to describe a business model from the structural point

of view.

On the other hand, in the behavioral viewpoint the

foremost element is the order in which processes are

performed. This depends on the interactions among

Weaving Business Model Patterns - Understanding Business Models

497

participants and resources, and defines dependencies

between activities: since the outputs of an activity

are the inputs of the next one, flows are thus estab-

lished both within and between the processes. These

flows can be of Cash, Information, or Value: they rep-

resent the main, transversal linkage between compo-

nents in the business model. The study of flows is thus

necessary for the understanding of a business model.

Unfortunately, current representations are not expres-

sive enough for describing them and leave them to be

figured out by the readers intuition. The following

section presents a proposal that tackles precisely this

problem.

3 RE-UNDERSTANDING

BUSINESS MODELS

The conceptualization of a business model which

we propose to fully describe a business model, in-

cluding both the structural and behavioral aspects, is

grounded in the following types of building blocks:

Zones, Flows and Channels, Gateways, and Proces-

sors. These are described in the following pages and

their role in a business model structure is discussed,

along with the way in which they interact with each

other. Together with the description of the concepts,

we present a graphical representation for the business

models.

3.1 Zones

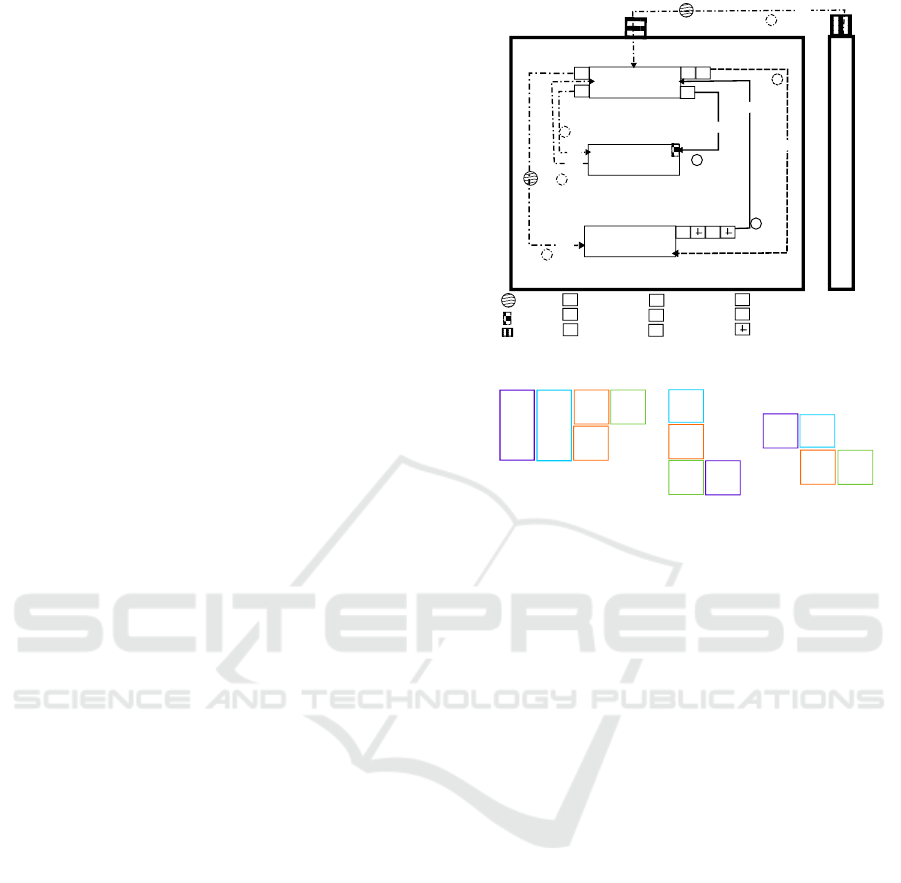

A Zone represents a core process in a business model.

A Zone contains participants, resources, flows, chan-

nels, and gateways (see Figure 2): participants per-

form activities which generate flows and define se-

quences depending on the order of generation, and the

origin and target of each flow. Each zone also has a

frontier to determine the process’ scope and the points

where interactions with other zones are established.

Processors act as mediators between zones and are de-

picted in the frontier of zones.

Figure 3 presents three ways in which the four

zones (S: Supply, T: Transformation, D: Delivery, M:

Monetization) can be organized in order to describe

different interactions in the model. Some models

present more than four zones which means that they

perform one or more of the four core processes in dif-

ferent ways. For instance, a business may gather raw

materials from two different suppliers, involving dif-

ferent activities and participants interacting at differ-

ent times.

Every zone includes participants, resources, activ-

ities, flows, gateways and processors. What varies

Participant 2

Participant 1

Participant 3

2

5

1

4

7

A1

A2

A3 A4

A5 A6

A7

ZONE

ZONE

Gateway

A1

Activity

A2

A3

A4

A5

A6

A7

A8

Time

End

Processor

3

6

Activity

Activity

Activity

Activity

Activity

Activity

Activity

$

In

In

In

In

V

V

V

$

In

Value

Cash

Information

Figure 2: A Zone and its components.

T

S

D

M

D

T

D

M

S

T

D

M

S

Figure 3: Organization of Zones in a Business Model.

among them are the actual components, which de-

pend on the specific process represented. For exam-

ple, the Supply zone might involve participants such

as suppliers and clients, and activities such as placing

orders, while the Delivery zone contemplates partici-

pants like distributors and activities like transporting

the product.

3.2 Flows and Channels

A flow can be defined as a continuous relation be-

tween two participants, resources, or activities, estab-

lished through a channel. The channel connects the

output of its starting point to the input of the ending

one. Flows can be characterized into three types. If

the output is a document, a communication, or any

other type of data, the flow is an information flow.

If the output is a product or service, it is a value flow.

And finally, money outputs mean that it is a cash flow.

Figure 2 presents the way in which flows are rep-

resented inside a zone. Since there is no structural

difference between the flow and the channel, they are

represented as one sole component. Value flows are

presented with a black solid line. They appear as

suppliers provide raw materials, as the business trans-

forms them into the desired product, and as they are

delivered and acquired by the client. It is thus possible

to say that the business and the client establish a value

flow as the latter acquires a product or service in ex-

change for money. This last element is associated to

ICEIS 2016 - 18th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

498

the cash flow, which is presented with a dashed line.

As it was mentioned, there is a cash flow every time

that a payment takes place, which leads to the appear-

ance of these flows in scenarios such as the business

paying to its suppliers and intermediaries. The infor-

mation flow, presented with a chain like line, gener-

ates every time there is a communication and infor-

mation is exchanged.

The three types of flows can be found inside zones

and between them because there are also cause-effect

relations between processes. Figure 4 shows an inter-

action between zones, established by the tree types of

flows. These flows cross the different zones through

processors, the fourth type of component that will be

presented.

3.3 Gateways

As flows relate processes and the components within

them, it is necessary to know when variations in vol-

ume take place. If the volume of a flow changes, it

may be related to a change in the relation between the

two connected agents. For instance, if business sales

decrease, it may be due to an alteration in the relation-

ship with the client. In order to know this, a gateway

is used to control the flow.

A gateway is defined as a control mechanism that

regulates flows among zones or agents, depending on

the quality of the relationship among them. Acting

as a push-pull mechanism, the gateway is able to tell

whether a relationship has changed and if so, the way

in which the volume varies. If a relationship wors-

ens, the flow is pushed, and if it gets better, it will

get pulled. In the business, the gateway may be rep-

resented by an area or actor in charge of looking after

the relationships. Figure 4 presents the gateway as a

waved circle crossed by a flow.

3.4 Processors

Processors are the most complex building block since

they depend on the zones that are being connected,

and the flows that cross them. A processor is defined

as the entry and exit point of a zone, capable of allow-

ing a certain type of flow cross the zone and interact

with the elements inside another.

Figure 4 shows three types of processors that cor-

respond to the three types of flows. The squares repre-

sent the information processor, the rectangle the value

one, while the pentagon the cash one.

As processors allow the circulation of flow

through zones, they permit the cause-effect relations

that trigger the execution of an activity or process and

at the end, they establish the connection between the

Participant

2

8

9

3

A1

A4

A5

ZONE

ZONE

Gateway

A1

A2

Activity

A3

A4

A5

Time

End

Processor

A3

1

5

4

7

ZONE

6

A2

Activity

Activity

Activity

Activity

Participant

Participant

Participant

In

In

In

In

In

V

V

V

$

V

$

In

Value

Cash

Information

Figure 4: Connected Zones.

processes. Figure 4 presents a view of several zones

connected through flows crossing processors. This in-

tertwining of processors and flows is like weaving a

business model.

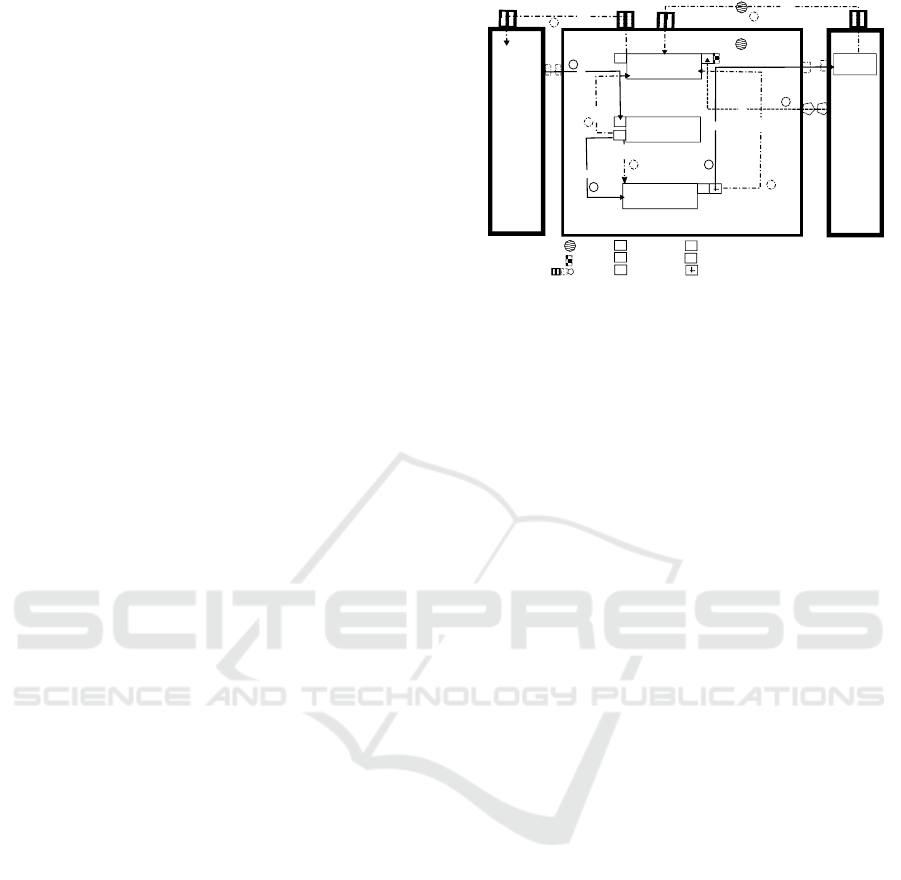

3.5 Meta-model

To formalize the structure for the understanding of the

business model that was just presented, a meta-model

was built. A graphical representation using UML is

shown in figure 5. In this figure, it is possible to see

the business model and the decomposition into four

processes with the correspondent structural and be-

havioral elements. By identifying the elements that

compose the meta-model, it is possible to represent

many business models regardless of the product or

service being offered.This is possible since the rep-

resentation process is not defined by the value propo-

sition, but by the main building blocks that lead to

the composition of the business model. When the

zones are defined, so are the core processes, which

in turn explains the way in which the business per-

forms its different activities. Moreover, by recogniz-

ing participants and resources, the business model de-

scription is enriched and the different relationships in

it are defined. As these relationships are character-

ized, flows begin to emerge and the business recog-

nizes the points where money, information and value

are exchanged.

4 BUSINESS PATTERNS

The difference between business models is explained

not only by differences in their component’s structure,

but also in the behavior and interaction among them:

the unique combination of processes and the way in

which they interact is what explains why each busi-

ness operates the way it does.

Weaving Business Model Patterns - Understanding Business Models

499

Zone

Transformation

Monetization Resource

Revenue

Supply

Delivery

Pattern

1

1

1

*

BusinessModel

1

*

Flow

1

*

Cash

Value

Information

Processor

Gateway

1

*

1

*

PCash

PValue

PInformation

* 1

* 1

* 1

Participant

1

*

Supplier Distributor Business Client Activity

1

*

Frontier

11

11

1

1

Figure 5: Business Model Metamodel.

It is fair to assume that the transformation pro-

cess is unique for each business since it is the core

point where value is added, where the actual strategy

of the company is evidenced, and where competitive

advantages are created. On the other hand, the sup-

ply, delivery and monetization processes do not differ

enormously from one model to another. In fact, there

is enough bibliography describing alternative designs

and methods on each one of these topics to safely as-

sume that each possible configuration for these pro-

cesses has already been described somewhere (e.g.,

the ever expanding supply-chain corpus).

Considering this, we attempted to collect a sig-

nificant number of the possible configurations for the

Supply, Delivery, and Monetization processes in order

to organize a catalog of Business Patterns. The goals

behind this where two. Firstly, a pattern can be under-

stood as a known solution to a well-known problem

(Gamma et al., 1995). Therefore, by building the cat-

alog we are making these solutions more accessible

to those that are defining their business model, or re-

defining their existing one. Secondly, we attempted to

create a structured body of knowledge about business

models which can be analyzed and used as the base

for the definition of new businesses. In this sense,

the catalog provides a set of building blocks to define

a new business model under restrictions or expecta-

tions.

The sources for the catalog included standards

such as the SCOR framework (Supply Chain Council,

2008) and Osterwalders monetization patterns. For

the moment patterns in the catalog only cover the

business aspects of each process. However, it should

be possible to expand the catalog in order to include

aspects such as typical IT support for each situation

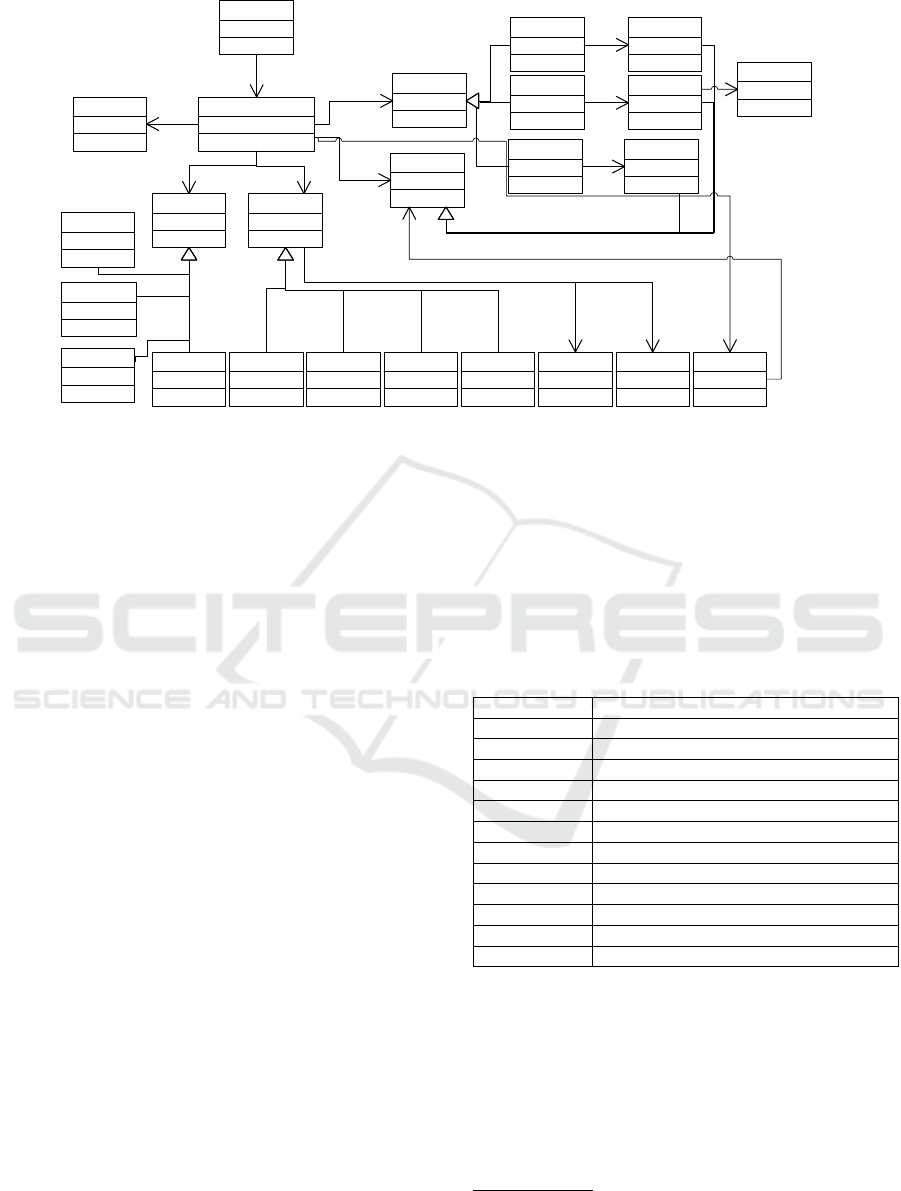

described in the catalog (see table 1).

The following pages present an extract of the pat-

terns from the catalog, selected for illustration pur-

poses. For each pattern a diagram is presented to il-

lustrate the activities and flows within each zone. Fur-

thermore, the interaction with the other zones are also

presented.

1

Table 1: Business Patterns Catalog.

CATEGORY PATTERN

Supply S1 - Source Stocked Product

Supply S2 - Source Make to Order

Supply S3 - Source Engineer to Order

Deliver D1 - Deliver Stocked Product

Deliver D2 - Deliver Make to Order Product

Deliver D3 - Deliver Engineer to Order Product

Deliver D4 - Deliver Retail

Monetization M1 - Asset Sale

Monetization M2 - Advertising

Monetization M3 - Freemium

Monetization M4 - Licensing

Monetization M5 - Usage Fee

4.1 Supply Patterns

Supply patterns explain the way in which a business

acquires raw materials from its providers. The follow-

ing are three patterns extracted from the SCOR frame-

work: source stocked products, source make to order

and source engineer to order. Each pattern presents

1

The complete catalog can be found in the fol-

lowing URL http://backus1.uniandes.edu.co/ enar-

dokuwiki/doku.php?id=wpatterns.

ICEIS 2016 - 18th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

500

three main agents: the supplier, which typically is a

different organization; business logistics, which are

the coordinator of supply management activities; and

the warehouse which stores and organizes supplies.

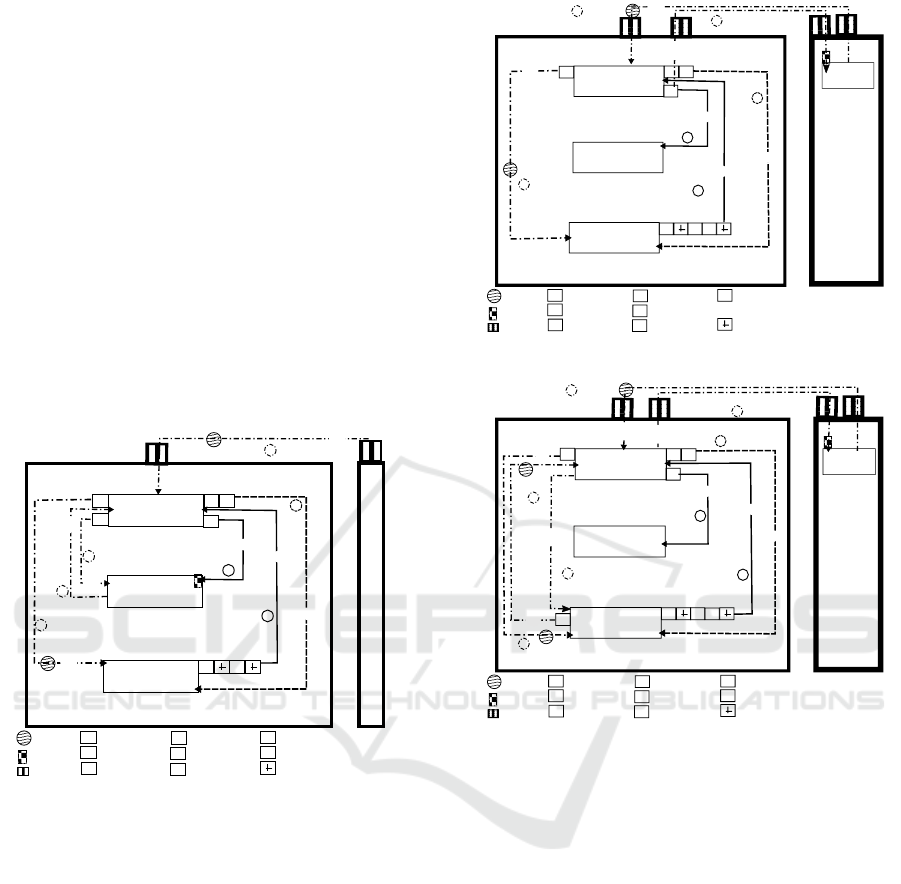

S1 - Source Stocked Product. The first pattern

describes a supply process in which orders are made

to maintain a stock of raw materials that allow the ful-

fillment of clients’ orders in a defined period of time.

This pattern is triggered by the client’s demand (1)

which tells the business the amount of product that

may be needed and, consequently, the amount of sup-

plies that must be ordered. Inventory is then checked

(3), and necessary materials are ordered (4) based on

actual inventory levels. Afterwards, the supplier pre-

pares the order, which involves a certain time lead

time, and then submits the raw materials (5). The

business receives the order, for it (6), and stores the

received materials in the warehouse (7).

Warehouse

Logistics

Supplier

2

5

1

4

7

A1

A2

A3 A4

A5 A6

A7

SUPPLY

MONETIZATION

Gateway

Demand

Order

Raw Materials

Raw Materials

Payment

A1

Picking

A2

Generate Order

A3

Place Order

A4

Load Order

A5

A6

Deliver Order

Receive Order

A7

Pay Order

A8

Store

Time

End

Processor

3

Inventory

Request

6

V

$

In

Value

Cash

Information

In

In

In

In

V

V

$

Figure 6: Source Stocked Product.

S2 - Source Make to Order. This pattern

describes a supply process in which raw materials are

produced and delivered based on a client’s order. In

particular, once the order is placed (1), an information

flow tells the supplier that the product must be made

(2). Once the product is ready it is delivered to the

business (3) which in turn pays for the supplies (4)

and stores them in the warehouse (5).

S3 - Source Engineer to Order. This supply pat-

tern describes a supply process in which raw mate-

rials are designed, produced and delivered based on

an order (1). In particular, there is a negotiation

event where the final product design (2) is defined (3).

Later, there is a placed order (4) that indicates the sup-

plier that the product must be produced and delivered.

Once the supplies arrive (5), the payment is done (6)

and the materials are stored (7).

Warehouse

Logistics

Supplier

2

3

1

4

5

A1

A2

A3

A5 A6

A7

SUPPLY

MONETIZATION

Gateway

Request

Order

Raw Materials

Raw Materials

Payment

A1

A2

Generate Order

A3

Place Order

A4

Make Order

A5

A6

Deliver Order

Receive Order

A7

Pay Order

Store

Time

End

Processor

A4

6

Order Ready

Client

V

$

In

Value

Cash

Information

V

V

$

In

In

In

Figure 7: Source Make to Order.

Warehouse

Logistics

Supplier

2

7

6

5

A1

A3

A4

A6 A7

A8

SUPPLY

MONETIZATION

Gateway

Request

Design

Raw Materials

Raw Materials

Payment

A1

A2

Generate Order

A3

Negotiation

A4

Place Order

A5

A6

Produce Order

Deliver Order

A7

Pay Order

Store

Time

End

Processor

A5

8

Order Ready

A2

1

4

Approval

3

Order

A8

Verify Order

Client

V

$

In

Value

Cash

Information

V

V

In

In

In

In

In

$

Figure 8: Source Engineer to Order.

4.2 Delivery Patterns

The second core process in the business model, de-

livery, initiates after value is transformed. Delivery

patterns include two types of participants: distribu-

tors and final clients. It is important to note that the

distributor can represent the business itself, or a third

party in charge of the activity. We now present four

delivery patterns extracted from the SCOR frame-

work.

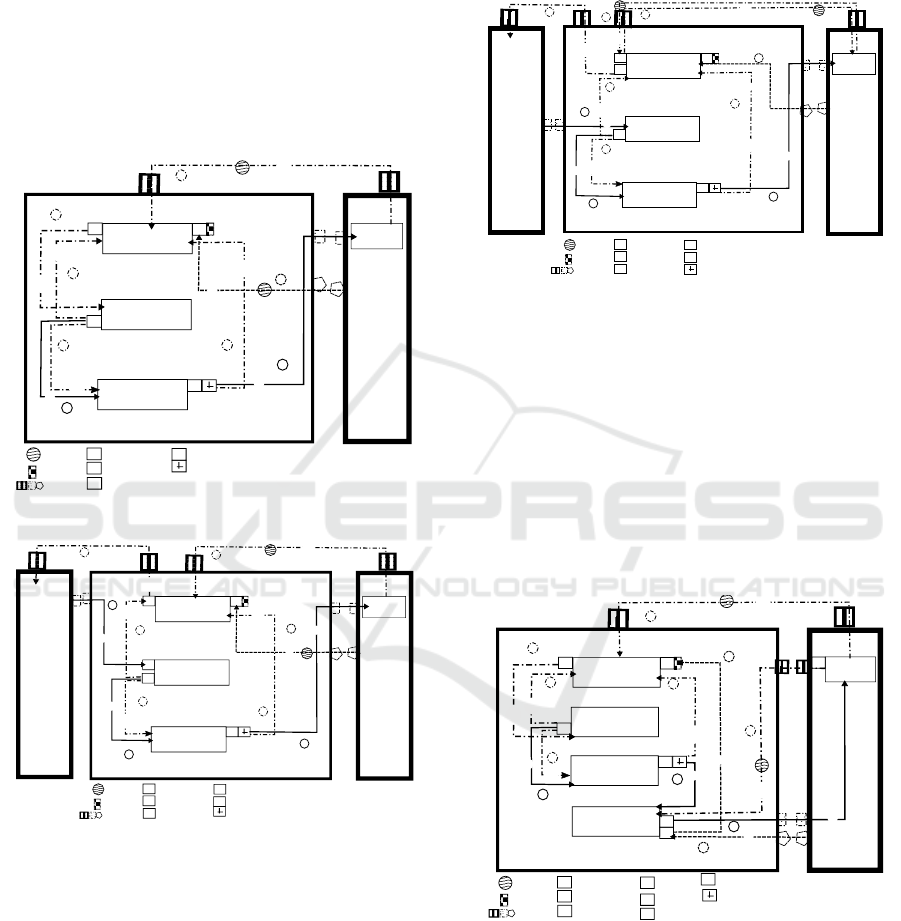

D1 - Deliver Stocked Product. The first pattern

describes a process in which the client maintains a

stock of the product offered by the company. Af-

ter the client’s order(1) is placed (2), the product is

picked from the warehouse (3,4) and delivered (5).

Once it reaches the client (6,7), the payment is re-

ceived (8). Depending on the relationship quality be-

tween the client and the business, the product demand

may vary. See Figure 9.

D2 - Deliver Make to Order Product. The sec-

ond pattern describes the distribution of products that

Weaving Business Model Patterns - Understanding Business Models

501

are manufactured or provided given a client’s order.

In this case, an order is placed (1) along with the key

information to initiate value transformation. These el-

ements are recognized by the distributor and commu-

nicated into the value transformation zone(2). After

the production and lead time are over, the product is

placed in the warehouse (3,4) and dispatched (5,6).

Once the order is delivered and received by the client

(7,8), the payment is received (9). Like the previous

pattern, the relationship with the client determines the

amount of product ordered.

Warehouse

Logistics

2

6

8

5

A1

A3

A4

DELIVER

MONETIZATION

Gateway

Order

Order

Product

Product

Payment

A1

A2

Place Order

A3

Picking

A4

Deliver Order

Receive Payment

Time

End

Processor

A2

1

4

Status

3

Request

Client

Transportation

Status

7

V

$

In

Value

Cash

Information

V

V

In

In

In

In

In

$

Figure 9: Deliver Stocked Product.

Warehouse

Logistics

2

8

9

3

A1

A4

A5

DELIVER

MONETIZATION

Gateway

Order

Order

Product

Product

Payment

A1

A2

Place Production

Order

A3

Receive Product

A4

Dispatch Order

A5

Deliver Order

Receive Payment

Time

End

Processor

A3

1

5

Status

4

Request

Client

Transportation

Status

7

TRANSFORMATION

6

Product

A2

V

$

In

Value

Cash

Information

V

V

V

$

In

In

In

In

In

Figure 10: Deliver Make to Order Product.

D3 - Deliver Engineer to Order Product. The

third pattern describes the distribution of a product

whose design and production are defined and trig-

gered by the client. Since the process involves an

order and a negotiation, it begins with the client com-

municating the desired design and conditions of the

distribution and payment (1). This information is de-

livered to the business, evaluated, and communicated

to the client (2). When the negotiation is complete,

the order is placed (3) and the distributor proceeds

to communicate the clients final design, and adjust

the distribution requirements. Once the product is

ready(4), it is stored in the warehouse (5) where it

is picked and dispatched (6,7). After the expected ar-

rival time, the client receives the product (9-10) and

pays for it (11).

Warehouse

Logistics

2

9

11

4

A1

A4

A5

DELIVER

MONETIZATION

Gateway

Design

Approval

Product

Product

Payment

A1

A2

A3

Place Order

A4

Dispatch Order

A5

Deliver Order

Receive Payment

Time

End

Processor

A3

1

6

Order

3

Order

Client

Transportation

Status

10

TRANSFORMATION

7

Product

A2

5

Status

Negotiation

V

$

In

Value

Cash

Information

In

In

In

In

In

In

V

V

V

$

Figure 11: Deliver Engineer to Order Product.

D4 - Deliver Retail. The final delivery pattern de-

scribes a special type of business model: Retail. In

this case, the distributor delivers the final product to

a spot where clients acquire it. As in markets, and

stores, this model considers clients acquiring the de-

sired value in a physical location; therefore, the deliv-

ery reaches a middle point. In particular, depending

on the demand (1), an order is placed (2), products

are picked (3,4,5) and the orders are delivered to an

intermediary (6,7). The latter sells(8) the product to

the client (9,10) and sends the payment (11).

Warehouse

Logistics

2

6

10

5

A1

A3

A7

DELIVER

MONETIZATION

Gateway

Demand

Order

Product

Product

Payment

A1

A2

Place Order

A3

Picking

A4

Deliver Order

Shop

Time

End

Processor

A2

1

4

Status

3

Request

Client

Transportation

Shopping

Order

8

Intermediary

A4

A5

9

Product

A6

11

Payment

A5

Sell

A6

Send Payment

A7

Receive Payment

Status

7

V

$

In

Value

Cash

Information

V

In

In

In

In

In

In

V

V

$

$

Figure 12: Deliver Retail.

4.3 Monetization

The third group of patterns is proposed taking into ac-

count revenue stream models adopted in the market.

Five different patterns are now presented, even though

there are some similarities between them. Actors in

these patterns are the business and the client that is

ICEIS 2016 - 18th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

502

acquiring or receiving the products and services pro-

duced (the ultimate recipients of value).

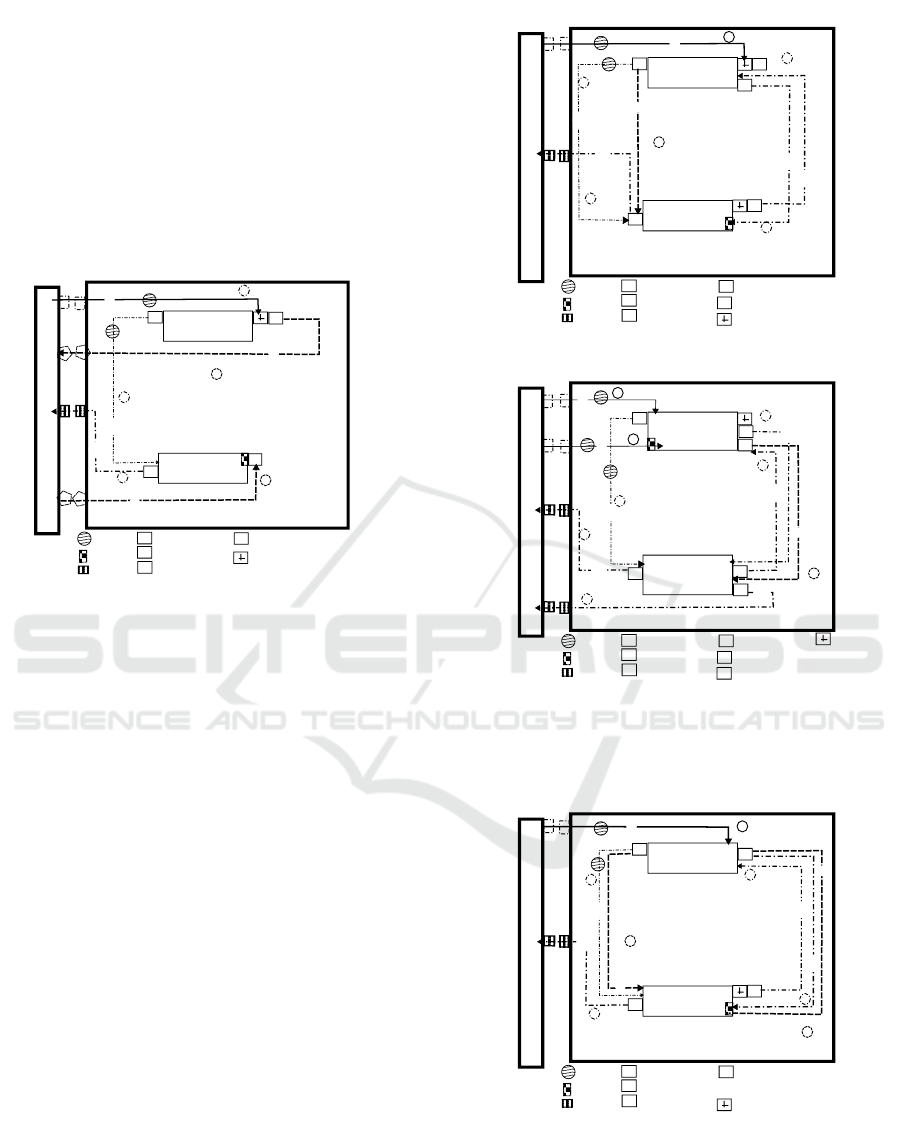

M1 - Asset Sale. The first pattern is perhaps the

most common one when it comes to monetization. In

this case, it describes value monetization based on a

onetime payment that the client does to buy the de-

sired product or service. It starts with an order placed

to the business (1) which triggers an order to deliver

(2) the product. Once the product reaches the client

(3), the payment is received (4,5).

Business

Client

2

1

A1

A2

A3

A4

MONETIZATION

DELIVERY

Gateway

Order

Payment

A1

Place Order

A2

Generate Request

A3

Pay

A4

Receive Payment

Time

End

Processor

3

Product

Request

4

Payment

5

V

$

In

Value

Cash

Information

$

$

In

V

In

Figure 13: Asset Sale.

M2 - Advertising. The second pattern describes

monetization based on advertisement. In this case, a

company generates revenue streams by giving clients

a space to advertise their own businesses or products.

The pattern starts with an agreement or contract (1)

that defines how long is a company able to advertise,

its value, and the granted space. This contract gener-

ates a payment (2) and an order (3) that grants the de-

fined conditions (4). Once the contract time is over, so

is the advertisement and the client is given the chance

(5) to extend renegotiate the contract or end it (6).

M3 - Freemium. The third pattern describes a

freemium model in which clients acquire the product

for free during a period of time, or with less charac-

teristics or functionalities. This pattern starts with a

client order(1) to receive value for free accepting cer-

tain constraints (Such as the time in which value will

be received, or the value that is accessible). Once the

order is placed (2), the product is delivered (3) until

the agreed time is over, or the client desires to request

premium(4). If it does so (5), a payment is received

(6) and the product is delivered or upgraded (7,8).

M4 - Licensing. The licensing pattern describes

a model based on the acquisition of a product or ser-

vice through a license, which is bought by a client

for a certain amount of time. The pattern starts with

a client that buys a license (1,2), this generates a re-

quest (3) that triggers the distribution of the product

Business

Client

3

1

A1

A2

A3

MONETIZATION

DELIVERY

Gateway

Agreement

Payment

A1

Sign Agreement

A2

Generate Request

A3

Receive Product

A4

Notificate

Time

End

Processor

4

Product

Request

2

A4

A5

5

Notification

6

Answer

A5

Negotiate

V

$

In

Value

Cash

Information

V

$

In

In

In

In

Figure 14: Advertising.

Business

Client

2

1

A1

A2

A5

MONETIZATION

DELIVERY

Gateway

Order

Payment

A1

Request Product

A2

Dispatch Order

A3

Request Premium

A4

Notificate

Time

End

Processor

3

Product

Request

6

A4

A3

Order

5

Contract

A5

Pay

A6

4

7

Request

8

Product

A6

Dispatch Order

V

$

In

Value

Cash

Information

$

In

In

In

In

In

V

V

Figure 15: Freemium.

(4). Once the license time is over (5), the client is

given the chance to renew it (6,7).

Business

Client

3

1

A1

A2

MONETIZATION

DELIVERY

Gateway

Order

Payment

A1

Buy License

A2

Generate Request

A3

Notificate

A4

Renew License

Time

End

Processor

4

Product

Request

2

A3

A4

5

Notification

6

Answer

Payment

7

$

In

Value

Cash

Information

V

V

In

In

In

In

$

$

Figure 16: Licensing.

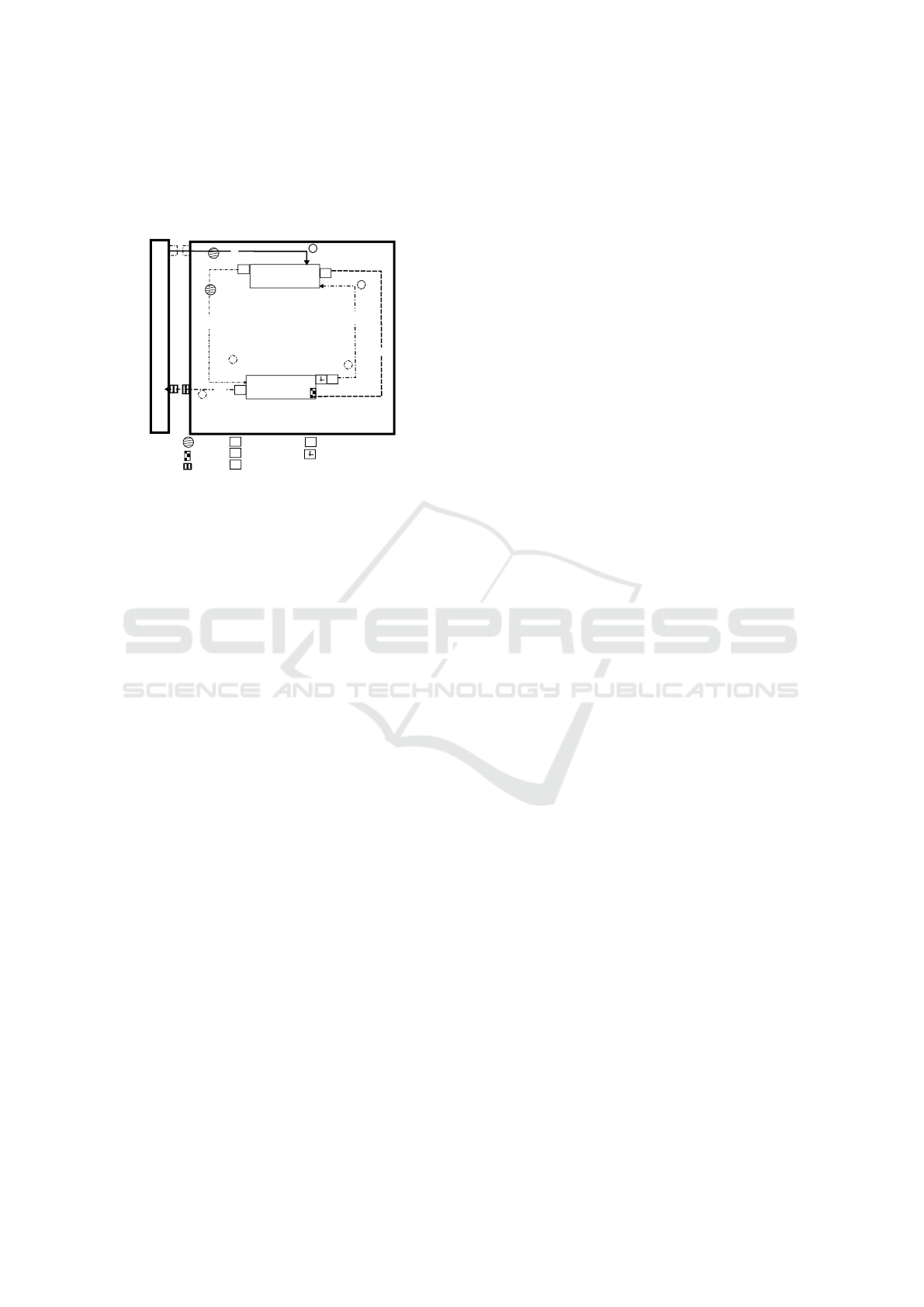

M5 - Usage Fee. The final monetization pattern

is usage fee, which describes a model in which the

business charges for the usage of its product. In this

case, a client places an order to use the product (1).

After it is delivered (2,3) and the billing period is over,

Weaving Business Model Patterns - Understanding Business Models

503

a bill is generated based on the usage (4) (That may

be quantified depending on the business). The client

pays (5) and may keep using the product as long as it

pays the bill.

Business

Client

2

1

A1

A2

MONETIZATION

DELIVERY

Gateway

Order

A1

Order

A2

Generate Request

A3

Generate Bill

A4

Pay

Time

End

Processor

3

Product

Request

A3

A4

4

Bill

Payment

5

$

In

Value

Cash

Information

V

V

In

In

In

$

Figure 17: Usage Fee.

5 RELATED WORK

Business models and the different behaviors that

emerge as they execute, have been matter of inves-

tigation for several authors. In particular, it is possi-

ble to find definitions and complete designs and repre-

sentations of what a business model should look like.

One of the most recognized efforts is Osterwalder’s,

who proposes both a structure for the model, and a

method to use it (Osterwalder and Pigneur, 2010).

Besides the well-known business model canvas, the

author proposes several patterns to take into account

when designing a business model. These patterns are

based on five types of business models: unbundled,

long tail, multi-sided, free and open business. Each

pattern is appropriate for certain types of businesses

(Osterwalder et al., 2014).

Business patterns established around the Rosset-

taNet standards are other example of designs consid-

ering business models. Though the standard considers

the interaction between participants with a business

purpose, it is possible to generate patterns that guide

the execution of a business model. In particular, it is

possible to generate patterns that describe order and

shipment processes and use them to evaluate the busi-

ness model execution (Telang and Singh, 2010)

Taking into account the scope of business mod-

els, patterns centered on specific elements are also

possible to find. For example, value-exchange pat-

terns have been designed after analyzing models of

real businesses. In these designs, agents and interac-

tions are specified taking into account what type of

value is being delivered. The visual representation is

also offered (Zlatev et al., 2004).

Moreover, efforts in generating guides for specific

audiences are also in existence. For example, there

is a business plan conception pattern language ori-

ented to support entrepreneurs in the conception and

design of their business models. Through a series of

questions and descriptions, key aspects of the busi-

ness model are addressed and depending on the con-

cerns of the entrepreneur, several solutions for fulfill-

ing them are offered (Laurier et al., 2010).

The amount of examples, patterns and guides gen-

erated towards the comprehension and adoption of

successful business models, is considerable. From

languages, to visual representations, to definitions,

there is a wide variety of options when it comes to de-

signing a business model. As it has been shown, these

patterns can derive from existing companies, frame-

works, or tendencies in the market. Regardless of

where they come from, their purpose remains simi-

lar: to guide and provide a standard in the design of a

business model.

Still, the expressiveness needed in order to com-

municate the business model approach described in

this paper, can not be achieved with the discussed

visualizations. Since there are five building blocks

that need to be considered (zones, flows and channels,

processors and gateways), it is necessary to count

with notations that allow their representation. In Os-

terwalder’s case although there is a notion of zones

and channels, the flow concept is implicit within the

canvas and the definition of the relationships among

agents turns out to be more complex. The e3-value

notation, on the other hand, is quite useful for the vi-

sualization of flows and processors, however, the de-

tail level is not enough for the purposes of the pro-

posed business model approach. In particular, since

e3 value groups the different types of flow in one type

(value), there is a need to define explicitly the element

that is flowing. Furthermore, there is not a clear rep-

resentation of the activities that lead to the flow es-

tablishment, and without, it is not possible to define

the resources or participants key in each relationship.

Considering the lack of a complete representation for

the building blocks and their components, defining a

new notation was appropriate.

6 CONCLUSION

A business model describes the way in which a busi-

ness receives and transforms inputs to create value

and build products and services which are then de-

livered and monetized. Even though the concept is

ICEIS 2016 - 18th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

504

simple and interpretations abound, it is not formal-

ized and there is a lack of comprehension of many

business models. Furthermore, the semantics of a

business model depend both on its structural features

(components and their relations) and its behavior. The

latter includes the interaction between these compo-

nents and especially the flow of information, cash and

value between them.

In order to understand both the structural and the

behavioral aspects of a business model, we have pro-

posed an interpretation based on the concepts of zone

(or processes), processors that connect zones, flows

that represent exchanges of value, information and

cash, actors which perform activities, and gateways

that regulate the exchanges. By using these elements

it should be possible to have a more profound under-

standing of business models in order to better com-

municate and analyze them.

Using this conceptualization, patterns for sup-

ply, delivery and monetization were identified in the

SCOR model and in the literature. Each pattern de-

tails a way in which a process can be performed, in-

cluding the participating actors, their activities, and

the exchanges of value, cash and information. De-

pending on the level of maturity of enterprises, these

patterns should serve to understand their business

models, or as a starting point for designing novel busi-

ness models based on well known solutions.

REFERENCES

Frick, J. and Ali, M. (2013). Advances in production man-

agement systems. sustainable production and service

supply chains. volume 415 of IFIP Advances in Infor-

mation and Communication Technology, pages 142–

149. Springer.

Gamma, E., Helm, R., Johnson, R., and Vlissides, J.

(1995). Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable

Object-oriented Software. Addison-Wesley Longman

Publishing Co., Inc., Boston, MA, USA.

Gordijn, J. and Akkermans, H. (2001). Designing and eval-

uating e-business models. IEEE Intelligent Systems,

16(4):11–17.

Laurier, W., Hruby, P., and Poels, G. (2010). Business plan

conception pattern language. In Kelly, A. and Weiss,

M., editors, CEUR Workshop Proceedings, volume

566, pages C4–1–C4–27. CEUR.

Lindgren, P. and Rasmussen, O. (2013). The business model

cube. Journal of Multi Business Model Innovation and

Technology, 1(3):135–180.

Osterwalder, A. and Pigneur, Y. (2010). Business Model

Generation: A Handbook for Visionaries, Game

Changers, and Challengers. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Osterwalder, A., Pigneur, Y., Bernarda, G., and Smith, A.

(2014). Value Proposition Design. John Wiley &

Sons, Inc.

Robu, M. (2013). The dynamic and importance of smes in

economy. The USV Annals of Economics and Public

Administration, 13(1(17)):84–89.

Supply Chain Council (2008). SCOR: Supply Chain Oper-

ations Reference Model Version 9. The Supply Chain

Council, Inc.

Telang, P. and Singh, M. (2010). Abstracting and apply-

ing business modeling patterns from rosettanet. In

Maglio, P., Weske, M., Yang, J., and Fantinato, M.,

editors, Service-Oriented Computing, volume 6470 of

Lecture Notes in Computer Science, pages 426–440.

Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

Zlatev, Z., van Eck, P., and Wieringa, R. (2004). Value-

exchange patterns in business models of intermedi-

aries that offer negotiation services.

Weaving Business Model Patterns - Understanding Business Models

505