Expressive Icons for the Communication of Intentions

Julio Cesar dos Reis

1

, Cristiane Jensen

2

, Rodrigo Bonacin

2,3

, Heiko Hornung

1

and M. Cecilia C. Baranauskas

1

1

Institute of Computing, University of Campinas, Campinas, São Paulo, Brazil

2

Faculty of Campo Limpo Paulista, Campo Limpo Paulista, São Paulo, Brazil

3

Center for Information Technology Renato Archer, Campinas, São Paulo, Brazil

Keywords: Icons, Emoticons, Meanings, Intentions, Pragmatics, Communication, HCI.

Abstract: The mutual understanding of intentions is essential to human communication. A web-mediated

communication lacks elements that are natural in face-to-face conversation. This fact requires treating

intentions more explicitly in computer systems. Literature hardly explores design methods and interactive

mechanisms to support users in this task. In this article, we argue that icons representing emotions play a

central role as means for aiding users to express intentions. This research proposes a method to determine

and refine icons aiming to represent and communicate the users’ intentions via computer systems. The work

explores a theoretical framework based on Speech Act Theory and Semiotics to analyze different classes of

intention. The method is experimented in a case study with 40 users and the obtained results suggest its

feasibility in the process of filtering, selecting and enhancing icons to communicate intentions.

1 INTRODUCTION

During a communication act, humans rely on

various resources for better expressing their ideas,

intentions and emotions. These resources include

gestures and facial expressions, which indicate how

to interpret the communication acts.

A key aspect of communication refers to the

shared understanding of intentions. Illocutions (acts

performed by a speaker in producing an utterance)

may result in different pragmatic effects depending

on the interpretation of the speaker’s intentions. For

example, the phrase “please, leave the room” can be

interpreted as an order/command or a gentle request.

This might depend on the situation, intonation and

corporal expressions. Although some words can

characterize intentions, such as, “suggest”, “ask”,

“expect” and “apologize”, in many situations the

speaker’s intentions are formulated in an implicit

way, without explicit use of words that indicate the

real intentions.

In computational systems, in which

communication remains predominantly based on

text, intentions are not always clearly stated and

shared. In some cases, the involved parts are unable

to perform a successful communication. Thus,

inadequate design solutions can imply in various

interaction barriers, resulting in several cases of

misunderstandings and disagreements between the

participants (Hornung et al., 2012).

These problems can create difficulties for users

to manage, retrieve and interpret the available

content, as well as interact effectively and

satisfactorily with others. A possible solution would

be to automatically capture and infer the intentions

by using natural language processing techniques.

However, this task is extremely complex, once the

interpretation is highly dependent on social and

cultural patterns.

Although recent research literature has addressed

some pragmatic aspects in interaction design

(Hornung and Baranauskas, 2011), there is still a

lack of interactive solutions and techniques to allow

users to explicitly declare their intentions using

computer systems. Our previous investigations

preliminarily studied ways of supporting users

dealing with these issues (Jensen et al., 2015).

Nevertheless, novel techniques and concrete design

solutions are still required to enable users to express

their intentions directly.

Whereas the use of so-called emoticons in

interactive interfaces has been exploited to support

the expression and transmission of emotions (Huang

et al., 2008), we argue that icons can also bring

benefits to the communication by supporting users in

expressing their intentions.

388

Reis, J., Jensen, C., Bonacin, R., Hornung, H. and Baranauskas, M.

Expressive Icons for the Communication of Intentions.

In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS 2016) - Volume 2, pages 388-399

ISBN: 978-989-758-187-8

Copyright

c

2016 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

This study proposes a method to select, adapt

and design icons to express different classes of

intentions and thoroughly experiment it based on a

case study. We call these expressive icons created or

selected with the proposal of representing and

emphasizing users’ intentions “intenticons”. This

work makes the following contributions:

• Define a method, based on experiments with

users, aiming to associate emotional icons

with intentions;

• Present a case study applying the proposed

method aiming to select and adapt groups of

icons to express each class of intention.

This research adopts Semiotics (Peirce, 1958)

and Speech Act Theory (SAT) (Searle, 1969) as

frames of reference. The two theories provide means

to structure and classify intentions according to

different dimensions of the illocutions, as proposed

by Liu (2000). Based on this referential, the

proposed method includes several steps to select

icons with the users’ participation. The designers

and users also discuss and propose improvements in

the icons design in a participatory way.

We tested the method with 40 subjects, including

undergraduate students in a Bachelor in Information

Systems course. The results point out the quality of

the association between icons and classes of

intentions and reveal the effectiveness of the

proposal to achieve representative icons.

The article is organized as follows: section 2

presents the related work; section 3 defines the

theoretical framework; section 4 describes the

proposed method and the case study; section 5

presents the results and discusses them; section 5

finally draws conclusions and future work.

2 EMOTICONS IN

COMPUTER-MEDIATED

COMMUNICATION

According to Huang et al. (2008), Computer

Mediated Communication (CMC) brings additional

difficulties in sharing emotions due to limited means

of expressing them. One way to mitigate these

difficulties is by introducing special icons named

emoticons. These icons contribute to the creation of

a new language to express emotions in CMC

environments.

Studies of Huang et al. (2008) indicate positive

results highlighting the value of emoticons for

improving the CMC effectiveness and users’

satisfaction. The authors pointed out that, when

compared with text-based communications,

integrating resources such as emotive expressions

and gestures enhance the quality of information.

This may refer to the possibility of emoticons to

change the users’ perceptions and interpretation of

the received messages.

Users might feel more comfortable to express

emotions in interfaces with informal style. In this

sense, emoticons also contribute to increase the level

of interpersonal interaction, as they improve the

capacity of expressing emotions.

There are numerous studies about the

representation of emotions in CMC. These

researches indicate various advances in computer

communication mechanisms. Derks et al. (2008)

present an extensive review of studies that reveal

differences and potentials of CMC compared to

face-to-face communication. Based on the analyzed

studies, Derks et al. (2008) emphasize the richness

of emotions in CMC.

Emoticons are vastly disseminated in instant

message interfaces and social networks. However,

they can also be explored in professional settings,

such as professional discussion forums. Luor et al

(2010) investigated the effects of using emoticons on

the communication of instant messages about

professional tasks at the workplace. Their results

point out the potential of emoticons to increase the

expressiveness of text messages. The authors

reported that workers recognize the utility of

emoticons at the workplace. Other studies explored

the use of emoticons in various working situations.

For example, Thoresen and Andersen (2013) studied

the effects on the use of emoticons in the

organizational communication from a socio-

psychological perspective.

In this context, a relevant issue is how to choose

an icon suitable to communicate a felling on a

specific situation. Urabe et al. (2013) present a

system for recommending emoticons. Their results

demonstrate the effectiveness of a system for

recommending icons for 10 categories of emotions.

Their experiments also highlight users’ difficulties

in selecting an emoticon to represent the emotion

that they want to express.

Carretero et al. (2015) analyzed the use of

expressive speech acts by students during online

interactions. The study covers 13 types of expressive

acts, i.e., acts to express their feelings and emotions.

The results reveal that the use of typography

resources and emoticons can improve the

expressiveness in various situations, e.g., to thank or

apologize.

Expressive Icons for the Communication of Intentions

389

The surveyed studies mostly stress the

importance of emoticons for expressive CMC

interactions. Although users’ intentions are often

associated with emotions, the communication and

expression of intentions are hardly addressed in

literature. In contrast, our work focuses on the use of

icons to inform intentions.

Studies of Dresner and Herring (2010) adopted

Speech Act Theory to analyze the linguistic role of

emoticons in CMC. The authors emphasized that

emoticons do not always work as “emotional icons”;

they are also associated with other signs, which do

not have the primary role of transmitting emotions,

i.e., they are indirectly related to emotions. In

particular, Dresner and Herring (2010) investigate

the roles that the emoticons take as signs to express

approaches and intentions. Their results indicate that

emoticons assign the desired “illocutionary force”

within the related text.

Our research aims to further explore the process

of selection and design of emoticons when

considering their role of assigning illocutionary

force. We contribute with techniques to the design

and selection of suitable and expressive icons for the

communication of intentions.

3 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

In order to associate users’ intentions with icons, we

adopted the conceptual framework of Liu, which is

based on Speech Act Theory and Semiotics (Liu,

2000).

Semiotics is a discipline that studies signs, their

meanings and meaning-making processes. A sign is

something that represents something to someone in

some respect or capacity (Peirce, 1931-1958).

Among others, people use signs to share meanings

and express intentions. While Semantics studies the

relations between signs and objects, Pragmatics

studies the relation between signs and the behaviour

of sign-using agents (Peirce, 1931-1958).

The communication between a “speaker” and a

“hearer” can be studied with Speech Act Theory

(Liu, 2000). Speech Acts (Searle, 1969) are

utterances that have performative functions in

language and communication. Searle proposes four

types of Speech Act: locutionary acts, illocutionary

acts, propositional acts and perlocutionary acts. In

this work, we focus on locutionary and illocutionary

acts.

A locutionary act refers to the act of uttering an

expression. An illocutionary act carries the speaker’s

intentions that are to be perceived by the hearer. The

effects of an illocutionary act on the hearer are

called perlocutionary effects. Perlocutionary effects

comprise changes of sentiments or mental states, and

perlocutionary acts are not necessarily linguistic.

A speech act or message can be distinguished

into two parts: the function and the content. The

content manifests a message’s meaning. Meaning

and interpretation are dependent on the environment,

in which the message is uttered, i.e., they depend on

the speaker and the hearer. The function specifies

the illocutions and reflects the speaker’s intentions.

Inspired by Speech Act Theory and based on

Semiotics, Liu (2000) proposed a framework for

classifying illocutions using three dimensions. One

dimension distinguishes between descriptive and

prescriptive “inventions”, another between affective

and denotative “modes”, and the last one between

different “times”, namely past/present and future.

If an illocution is related to the speaker’s

personal modal state mood, it is called affective,

otherwise denotative. If an illocution has an

inventive or instructive effect, it is prescriptive,

otherwise descriptive. The classification of the

“time” dimension is based on when the social effects

of the message are produced, i.e., in the future or the

present/past.

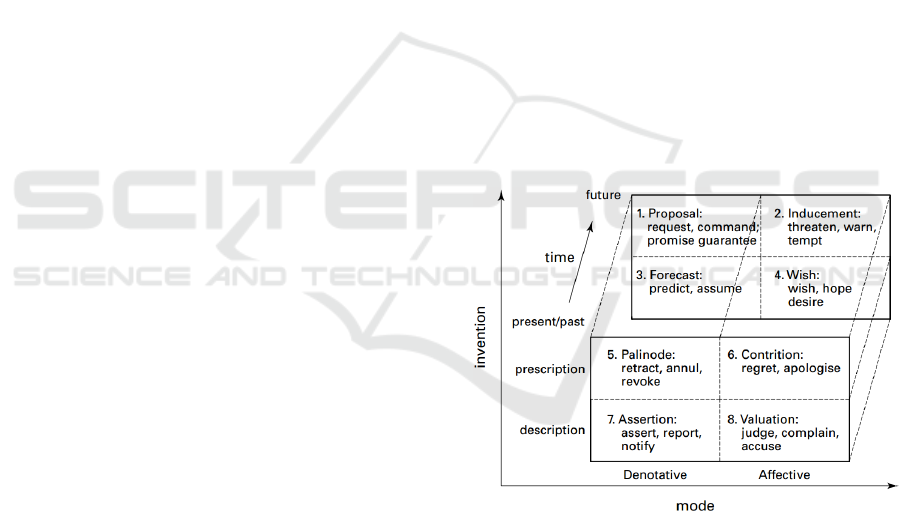

Figure 1: Classification of illocutions by Liu (2000).

The three dimensions result in eight different

classes (Figure 1): 1. Proposal (future, prescription

and denotative) — ask for something, order,

promise; 2. Inducement (future, prescription and

affective) — encourage someone, threat, suggestion;

3. Forecast (future, description and denotative) —

anticipate, suspect, imagine; 4. Wish (future,

description and affective) — plan, hope, desire; 5.

Palinode (present/past, prescription and denotative)

— undo, remove; 6. Contrition (present/past,

prescription and affective) — act of regret, excuse,

ICEIS 2016 - 18th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

390

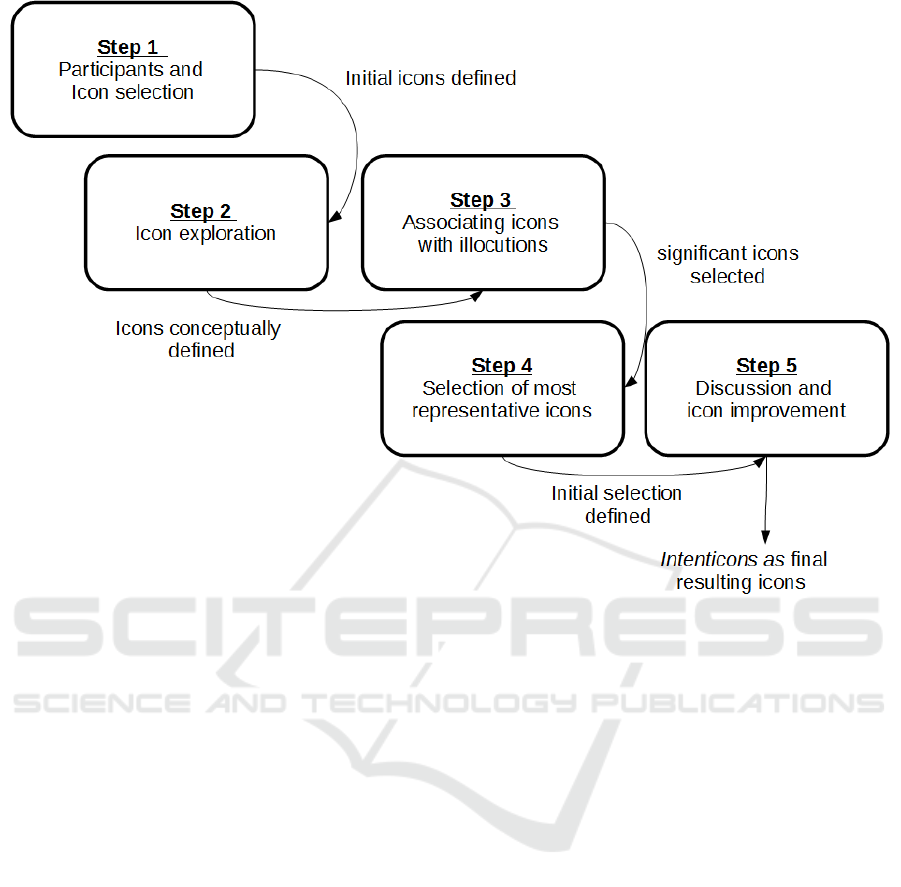

Figure 2: Five-step method defined.

justification; 7. Assertion (present/past, description

and denotative) — confirm, support, inform, declare;

8. Valuation (present/past, description and affective)

— assign value to something or someone.

4 METHOD AND CASE STUDY

Based on the theoretical framework outlined in the

previous section, we propose a method to determine

intenticons. Furthermore, we conduct a case study

applying the method in order to experiment it.

4.1 Proposed Method

The five-step method is inspired by the participatory

method “Icon Design Game” (Rocha and Baranauskas,

2003) for supporting designers in the creation of icons

and other graphical user interface elements. The

general objective of this method is to identify the “best”

graphical representation of a concept.

Figure 2 illustrates the five steps. First,

participants and an icon set are selected. Second,

participants explore the icons and freely associate

concepts (short phrases). Third, participants

associate icons with classes of illocutions. Fourth,

participants choose the most representative icons

from step three. Fifth, participants discuss and

possibly adapt the icon selection.

In the following, we describe the five steps in

more detail.

Step 1. Participants and Icon selection

1. Choose between 15 and 20 participants.

According to the authors’ experience, this

number has shown to be adequate for this kind of

activity.

2. Designers propose the initial set of candidate

icons.

3. Designers explain the objectives and the process

of the activities to the other participants.

Step 2. Icon exploration

1. Participants describe concepts they associate

with the icons on sticky-notes. At this point, the

participants do not know yet the framework

presented in section 3, i.e., concepts expressed

by the participants are uninfluenced by the

definition of illocution classes.

Expressive Icons for the Communication of Intentions

391

2. This process is iterative, one icon at a time. After

each icon, facilitators collect the created sticky-

notes.

Step 3. Associating icons with illocutions.

1. Designers create scenarios that illustrate the

illocutions.

2. Designers present classes of illocutions, one at a

time, using previously created illustrative

scenarios to exemplify illocutions in the context

of participants.

3. Participants individually write on sticky-notes

the identifiers of the icons they think best denote

the illocution, informing up to three icons in

decreasing order of significance.

Step 4. Selection of most representative icons.

1. Designers distribute lists of illocutions and the

respective icon set proposed during the previous

step.

2. Participants individually choose a unique icon

they think is most representative for each class of

illocution.

Step 5. Discussion and icon improvement.

1. Designers present the results of the previous

steps and conduct a debriefing with the

participants. Discussion topics include, but are

not limited to: possible changes in the

association of illocution and icon; additional

icons, in case no or few adequate icons where

identified for an illocution; ambiguities/conflicts

of icon-illocution association; removal of icons.

2. At the end of the discussion, the designers

present the final set of intenticons.

4.2 Case Study

The proposed method was applied during a case

study in the Informatics lab at the IASP faculty in

April 2015. The participants of the study included 2

HCI researchers with experience in interaction

design, who were responsible for the conduction of

the method, 1 graphic designer who designed the

initial icon set, 2 local lecturers who acted as

facilitators and 40 undergraduate students of an

Information Systems course.

All 40 students — aged 20 to 61, 12 female —

were in the seventh semester. The students and

facilitators participated of the activities during two

different days. On the first day, steps 1 to 4 were

conducted; during the second day, step 5 was

conducted using the focus group method.

The research materials such as annotation forms

were situated within the domain of software

programming. Sample phrases to represent illocution

classes were taken from an online forum about Web

development. For instance, a phrase to represent the

illocution class “proposal” (request, command,

promise, guarantee) was, “You might want to take a

look at HTML Media Capture”. For all illocution

classes, there was at least one representative phrase

previously selected by the researchers.

5 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The presentation and analysis of results explore the

following topics:

1. Selection and initial design of icons;

2. Theory-free assignment of concepts to icons;

3. Analysis of quantitative distribution of icons for

each class of illocution and initial selection;

4. Analysis of detected ambiguities;

5. Proposal of improvements in icons and

debriefing sections;

6. Final selection of intenticons

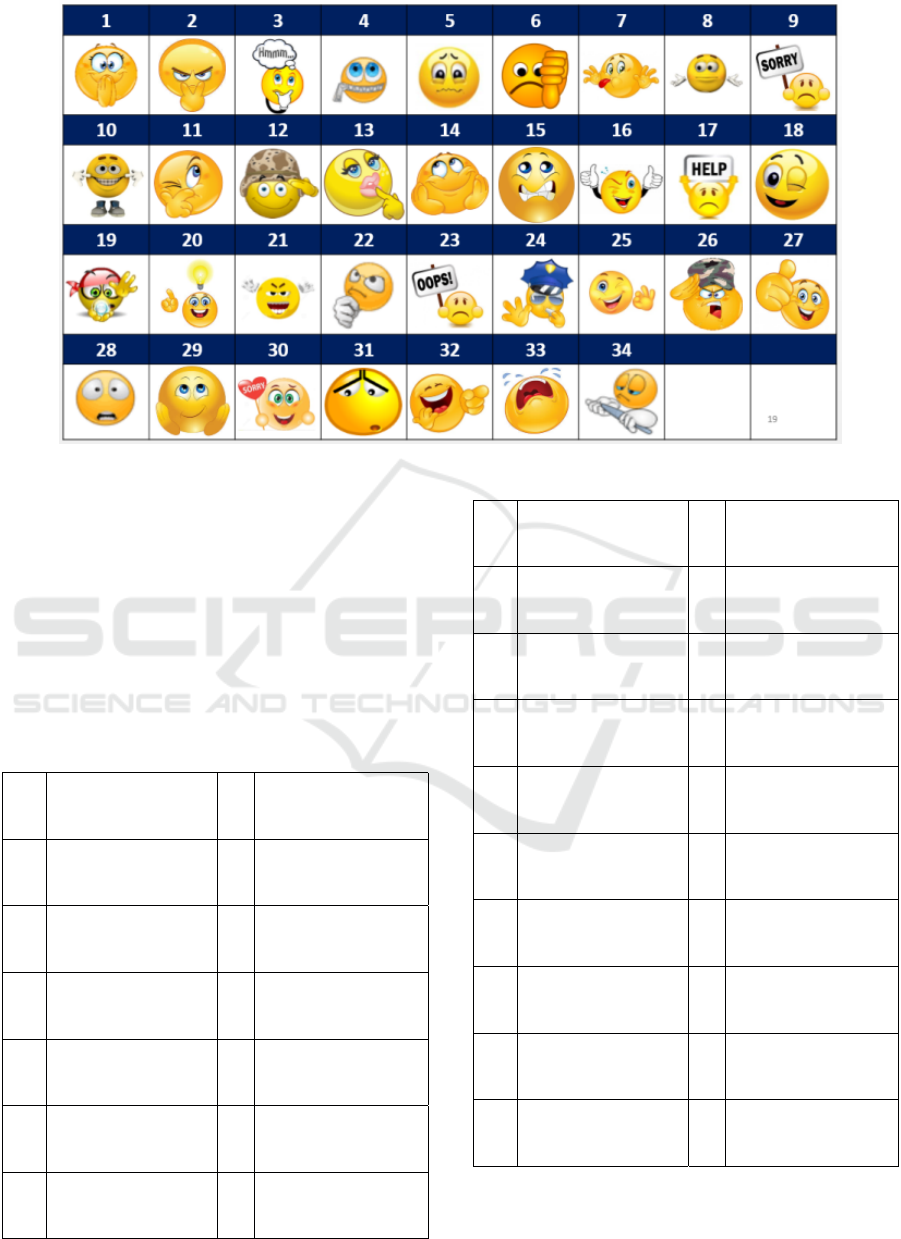

5.1 Selection and Initial Design of Icons

The initial icons were derived from preliminary

studies (Jensen et al., 2015) and from web searches

associated with keywords extracted from the classes

described in Figure 1. The goal was to obtain a

limited initial set; the selection criteria included the

relevance in making explicit intentions according to

the classes of illocutions. To this end, designers

selected images that had descriptions matching one

of the eight classes, and that were judged as

representing the respective class to some degree. A

graphic arts professional redesigned the icons to

maintain a uniform visual quality. Figure 3 shows

the initial set of obtained icons numbered from 1 to

34.

ICEIS 2016 - 18th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

392

Figure 3: Initial icon set numbered from 1 to 34.

5.2 Theory-free Assignment of

Concepts to Icons

Table 1 shows the three most frequent concepts that

participants assigned to each icon during the “icon

exploration” (step 2 of the method proposed in

section 4.1). These results also consider an analysis

performed by the involved researchers to detect the

most representative concepts for each icon.

Table 1: Concepts associated to the icons.

1

hopeful

anxious

timidity

18

cool

small wink

smartness

2

suspicious

watching over

keep an eye on

19

oracle

guessing

Forecasting

3

thoughtful

doubtful

imagining

20

Optimistic

idea

light

4

fear

silent

secret

21

frightening

angry

raging

5

underdog

sad

agonized

22

doubt

thoughtful

analytical

6

Deception

Disappointed

disapproved

23

Regretful

sheepish

mistake

7

kidding

playing

mocking

24

Attention

Stopped!

Stop!

8

It was not me!

doubt

confusion

25

OK!

sure

agreement

9

Apologies

sorry

Pardon

26

Yes sir!

prepared

Copy that

10

happy

Fake smile

forced laugh

27

greeting

great

Nice

11

suspicious

thoughtful

questioned

28

astonished

frightened

scared

12

Yes sir

Copy that

determined

29

deluded

in love

wishing

13

vanity

seductive

sensual

30

ashamed

Sorry my love!

Pardon

14

passionate

dreaming

gentle

31

Disappointed

unmotivated

upset

15

fear

apprehensive

worried

32

sarcastic

laughs

guffaw

16

happiness

wonder

Beauty!

33

deep sadness

crying

depressed

17

aid

help

lonely

34

inattentive

carefree

tedium

The results indicate that various used concepts

and terms depict people’s ordinary language. Several

Expressive Icons for the Communication of Intentions

393

verbs are used in the gerund form to portray the

action represented by the icon, e.g., crying.

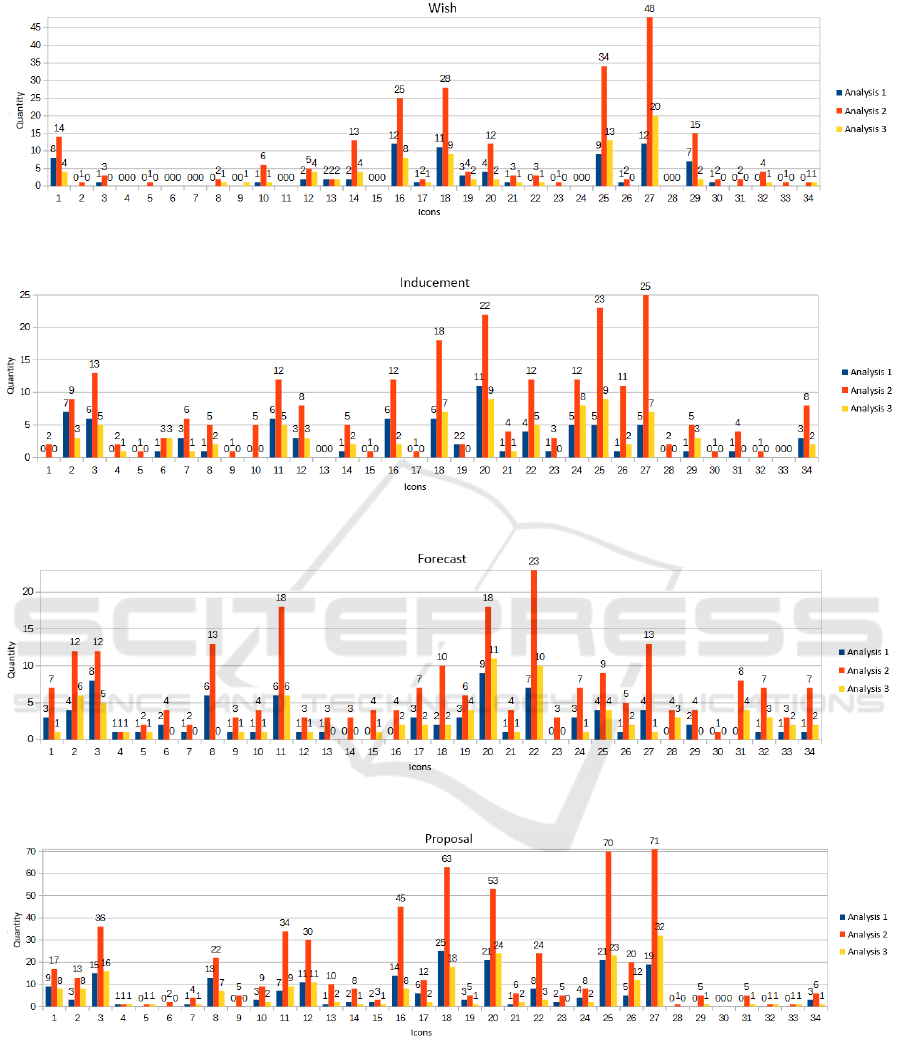

5.3 Analysis of Quantitative

Distribution of Icons for Each Class

of Illocution and Initial Selection

In order to determine the most relevant icons for

each class of illocution, we examined different

frequencies of participants’ assignments of icons to

illocution classes. Three separate analyses were

performed to understand the influence of icons

defined as the most significant and most

representative in Steps 3 and 4.

During analysis 1, we focused on how many

times an icon appeared with the highest priority

during Step 3 (Prio1). For analysis 2, we computed

how many times an icon appeared in any of the three

slots used during Step 3 (Top3). In analysis 3, we

counted how many times an icon was chosen as the

most representative for an illocution class during

Step 4 of our method (MostRep).

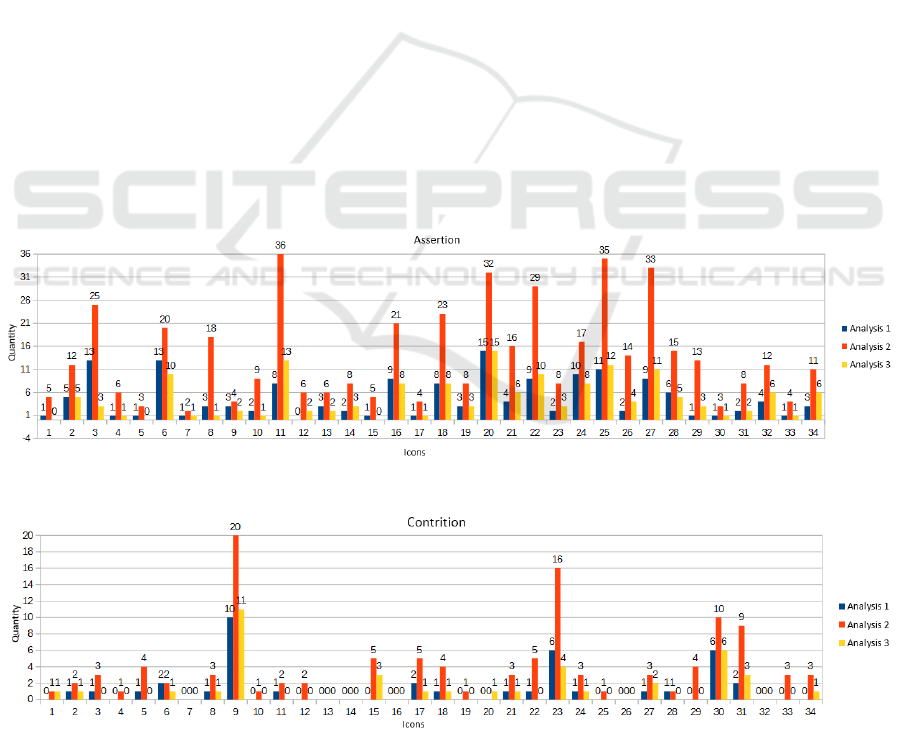

Assertion. Figure 4 shows results to the class

Assertion. Analysis 2 (Top3) indicates a small set of

icons that quantitatively differ from all others (e.g.,

icons 11, 25 and 27). For several icons, results of

Analysis 1 (Prio1) remain consistent with the

Analysis 3 (MostRep) because icons with higher

frequency in Analysis 1 are also those indicated with

greater frequency in Analysis 3.

Contrition. Figure 5 shows the results for the

class of illocution Contrition. Analysis 2 (Top3)

highlights a higher frequency of a few icons like 9

and 23. The significant difference with other icons

can indicate that icons 9 and 23 refer to potential

candidates to represent Contrition.

Wish. Figure 6 shows the results for the class of

illocution Wish. Aligned with the obtained results of

Analysis 2 (Top3) concerning Assertion, icons 25

and 27 are more frequently observed. In contrast, we

can indicate the icons 16 and 18 since they appear

more frequently than in the Assertion.

Inducement. Figure 7 shows the results for

Inducement. We can observe that icons with higher

frequency in Analysis 2 (Top3) also appear in

Analysis 1 (Prio1) and Analysis 3 (MostRep).

Forecast. Icons 11, 20 and 22 are the most

frequent in Analysis 2 (Top3) as shown in Figure 8.

Icon 22 is the most frequent in Forecast, and only in

Forecast, although it appears with a higher or

similar absolute frequency in assertion, proposal and

valuation.

Figure 4: Frequency distribution of assigned icons for the class of illocution Assertion.

Figure 5: Frequency distribution of assigned icons for the class of illocution Contrition.

ICEIS 2016 - 18th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

394

Figure 6: Frequency distribution of assigned icons for the class of illocution Wish.

Figure 7: Frequency distribution of assigned icons for the class of illocution Inducement.

Figure 8: Frequency distribution of assigned icons for the class of illocution Forecast.

Figure 9: Frequency distribution of assigned icons for the class of illocution Proposal.

Expressive Icons for the Communication of Intentions

395

Figure 10: Frequency distribution of assigned icons for the class of illocution Palinode.

Figure 11: Frequency distribution of assigned icons for the class of illocution Valuation.

Proposal. In Figure 9, icons 25 and 27 appear

with the highest frequency in Analysis 2 (Top3).

These icons also appeared relevant mostly in the

analysis for Wish and Inducement. Results allow

discarding less frequent icons, e.g., 4, 5 and 6.

Palinode. Results in Figure 10 for Palinode

show a great similarity with the distributions found

for Contrition, whose icons 9, 23 and 30 are more

frequent in Analysis 2 (Top3).

Valuation. Results for the illocution class

Valuation (Figure 11) are similar to those of

Proposal (Figure 9). Further analyses are required

taking users’ comments into account to elucidate

these differences (addressed in the next steps).

According to the quantitative analyses, designers

selected an initial set of intenticons for each

illocution class (Table 2), using the results from

Analysis 2 (appearance of the icons in the three slots

of step 3) as the main selection criterion.

5.4 Analysis of Detected Ambiguities

Table 2 indicates a repetition of several icons for

different classes of illocution, which potentially

reveal ambiguities among icons. In particular, we

observe that the participants deemed icons 27, 25, 20

and 18 as appropriate for the illocution classes

Proposal, Inducement, Desire and Valuation. This

result suggests the need of reworking these icons

because they present difficulties in their

interpretation.

Similarly, the icons 11 and 20 appear as

representative of both Forecast and Assertion.

Considering the dimensions in the illocution

classification framework (cf. Figure 1), even though

these two classes of illocution are organized into

different periods in the time dimension, they are in

the same invention and mode dimension, i.e., both

are denotative and descriptive. This scenario justifies

the qualitative debriefing that can further clarify

possible misunderstandings identified and mitigate

these issues.

Table 2: Intenticons initially selected.

Illocution

Intenticons

Assertion 11; 27; 25; 20; 22

Contrition 9; 23; 30; 15; 22

Wish 27; 25; 18; 16; 01

Inducement 27; 20; 25; 24; 18

Forecast 22; 11; 20; 03; 02

Proposal 27; 25; 18; 20; 03

Palinode 9; 23; 30; 15; 27

Valuation 27; 25; 18; 16; 20

ICEIS 2016 - 18th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

396

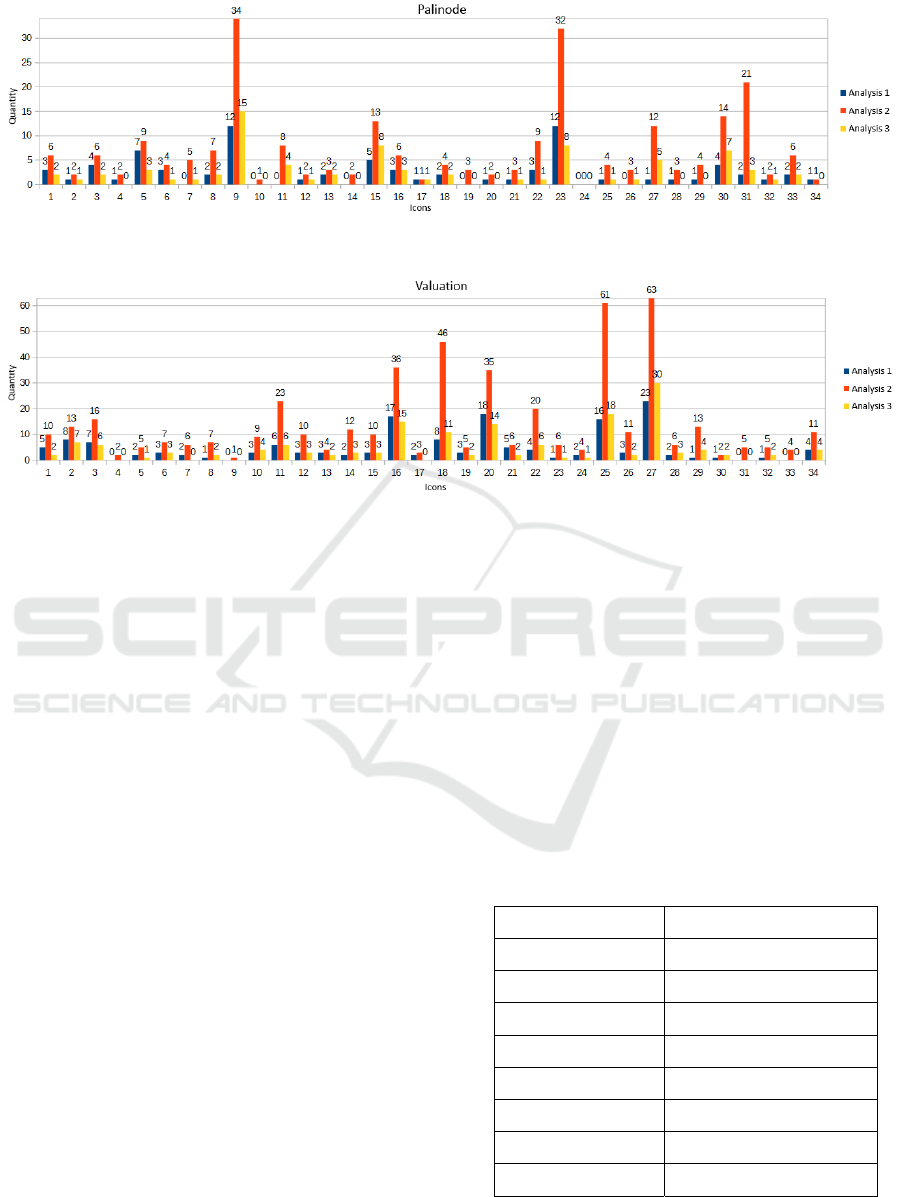

Figure 12: Additional Intenticons explored.

5.5 Proposal of Improvements in Icons

and Debriefing Sections

During Step 5, designers also introduced a new icon

set to encourage discussion (Figure 12). The new

icons are identified with letters from A to T. The aim

was to expand the diversity of choices for the

representation of classes of illocution. The results of

quantitative analyses informed the design of the new

icons, where alternatives were defined aiming to

minimize ambiguities.

This step involves a debriefing section based on

the results obtained from the previous steps. Firstly,

designers chose the five intenticons to represent each

class of illocution (Table 2). They presented to the

participants the intenticons to make an overview of

the different illocution classes. Prompted about the

detected ambiguities among illocution classes, the

participants reported that they had realized that

many icons were out of context for some classes of

illocutions.

The designers discussed the ambiguous

intenticons with the participants. Subsequently,

based on the initial selection of intenticons (Table

2), and considering the ambiguities as well as the

additional icons (Figure 12), the participants selected

at least three ambiguity-free intenticons.

More specifically, in the debriefing section,

designers passed through each intenticon asking the

participants to which extent each icon represented

the class of illocution. They then took into account

the participants’ opinion to make additions and

removals of icons in each class. Successively, they

carried out discussions concerning all intenticons

available. If any inaccurate case was detected, the

choices were jointly revised and decided which

category the icon best fit.

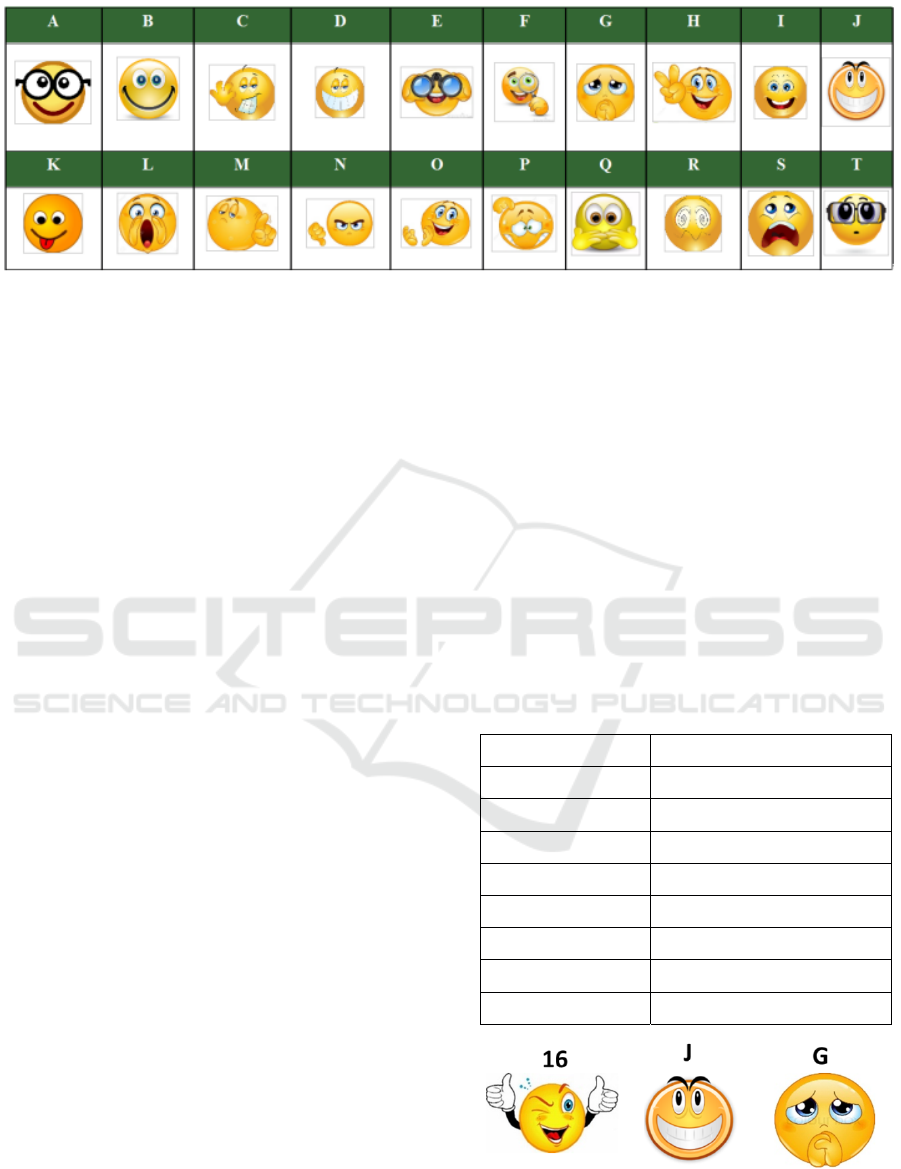

5.6 Final Selection of Intenticons

Table 3 shows the outcome of the selection of

intenticons based on the debriefing section

developed with the participants. We found that while

for some classes of illocution the initial selection of

icons remains in the final set (e.g., Proposal), for

some other classes, the selected icons were fully

reviewed. This may be due to the organization of the

debriefing section conducted, where designers did

not impose any restrictions to maintain icons in one

class or other. Figure 13 presents an example of the

final selection of intenticons to the class of illocution

Inducement. This result revealed the choice of new

icons that did not appear in the first selection.

Table 3: Final selection of Intenticons.

Illocution

Intenticons

Assertion 26; 12; O; A; D

Contrition P; R; N; 33

Wish 29; 14; 1

Inducement 16; J; G

Forecast 22; 11; 20; 03; 19; F

Proposal 27; 25; 18; C; H

Palinode 9; 23; 30; 31

Valuation I; K; 6; 10

Figure 13: Final selection of icons for the class of

illocution Inducement.

Expressive Icons for the Communication of Intentions

397

5.7 Discussion

This research explored a way of facilitating human

communication in computer systems. While

literature has studied icons to represent emotions,

few empirical studies exist for elaborating explicit

visual means to express intentions.

Results indicate the potential of the method to

identify and evaluate icons that represent intentions.

The initial steps of the method allow participants to

preliminarily experience the icons, and enable

designers to understand how users make sense of the

originally proposed icons. Furthermore, the method

enables a refinement of icons. The final selection

reached via debriefing sections might vary from the

initial selection. The initial selection is based on a

quantitative analysis, which might result in

ambiguous icons. The debriefing step is thus

required to improve icon selection.

Ambiguities might be related to several factors:

(i) participants might superficially interpret the

icons; (ii) the proposed icons might not be specific

enough; and (iii) participants might have difficulties

in understanding the illocution classes. In other

words, participants might not be able to make the

necessary distinctions between the existing classes

(e.g., between Palinode and Contrition), which can

influence the assigned icons during the execution of

the case study.

Therefore, further studies should address the

impact of these icons in specific application

contexts. The influence of user’s profiles in the

obtained results also requires additional

investigation, since this work focused on computer

science students as subjects in the case study. As

validation process, we plan to involve a second user

population, distinct from the participants of this

study. We aim to examine the extent to which the

obtained intenticons are relevant to different

communities and situations of communication.

The conducted quantitative analyses are likely to

affect the initial selection of intenticons. Future

research might investigate to what extent they can

influence the initial collection and the final results.

We also plan to study the impact of the context in

which intenticons are expressed with their

interpretation by users during communication tasks.

6 CONCLUSIONS

The sharing of intentions plays a key role in human

communication. Users require effective ways to

express their intentions more explicitly in computer

systems in order to enhance communication between

people. In this article, we argued that icons

expressing emotions can help users communicate

their intentions. We proposed a method to associate

icons with intention classes, through several steps,

representing a systematic approach to determine the

most appropriate intenticons. The method was

experimented in a case study yielding encouraging

empirical results. The proposed technique was

effective in selecting icons and enabled the detection

of ambiguities. The foreseen debriefing sections

were relevant for improving the selection and

mitigating inaccurate cases. Future studies involve

further quantitative and qualitative analyses that can

contribute with improvements to the method. We

aim also to conduct a thorough validation of the

obtained intenticons considering a distinct group of

users.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the São Paulo Research Foundation

(FAPESP) (Grant #2014/14890-0) and National

Counsel of Technological and Scientific

Development (CNPq) (Grant #308618/2014-9). The

opinions expressed in this work do not necessarily

reflect those of the funding agencies.

REFERENCES

Carretero, M., Maíz-Arévaloa C., Martíneza M. A. 2015.

An analysis of expressive speech acts in online task-

oriented interaction by university students. In 32nd Int.

Conference of the Spanish Association of Applied

Linguistics (AESLA), pp. 186 – 190.

Derks D., Fischer A. H., Bos, A. E. R. 2008. The role of

emotion in computer-mediated communication: A

review. Computers in Human Behavior, 24, 766–785.

Dresner E. & Herring S. C. 2010. Functions of the

Nonverbal in CMC: Emoticons and Illocutionary

Force. Communication Theory, 20, 249 – 268.

Hornung, H., & Baranauskas, M. C. C. 2011. Towards a

conceptual framework for interaction design for the

pragmatic web. In J. A. Jacko, Human-Computer

Interaction. Design and Development Approaches.

Heidelberg: Verlag - Springer. pp. 72 – 81.

Hornung, H.; Pereira, R.; Baranauskas, M. C. C.; Bonacin,

R.; Dos Reis, J. C. 2012. Identifying Pragmatic

Patterns of Collaborative Problem Solving. IADIS

International Conference WWW/Internet. Madrid,

Spain, pp. 379 – 387.

Huang, A. H; Yen, D. C. & Zhang, X. 2008. Exploring the

potential effects of emoticons. Information &

Management, pp. 466 – 473.

ICEIS 2016 - 18th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

398

Jensen, C. J.; Dos Reis, J. C.; Bonacin, R. 2015. An

Interaction Design Method to Support the Expression

of User Intentions in Collaborative Systems. In 17

th

International Conference on Human-Computer

Interaction (HCII’15). Los Angeles, CA, USA. LNCS,

Springer International. Vol. 9169, pp. 214 – 226.

Liu, K. 2000. Semiotics in Information Systems

Engineering. Cambridge University Press.

Luor T., Wu L., Lu H., Tao Y. T. 2010. The effect of

emoticons in simplex and complex task-oriented

communication: An empirical study of instant

messaging. Comp. in Human Behavior. 26, 889 – 895.

Peirce, C. S. 1931-1958. Collected Papers. Cambridge.

Harvard University Press.

Rocha, H. V., & Baranauskas, M. C. C. 2003. Design e

Avaliação de Interfaces Humano-Computador.

Campinas: NIED/UNICAMP.

Searle, J. R. 1969. Speech Acts: An Essay in the

Philosophy of Language. Cambridge University Press.

Thoresen T. H. & Andersen H. M. 2013. The Effects of

Emoticons on Perceived Competence and Intention to

Act. BI Norwegian Business School.

Urabe Y., Rzepka R., Araki K. 2013. Emoticon

Recommendation for Japanese Computer-Mediated

Communication. IEEE Seventh International

Conference on Semantic Computing, pp. 25 – 31.

Expressive Icons for the Communication of Intentions

399