A Health Virtual Community Perspective for Peripheral

Arterial Disease

The Need of an E-solution for PAD

Christo El Morr

1

, Peggy Ng

2

, Amber Purewal

3

, Courtney Cole

4

,

Musaad Al Hamza

5

and Mohamed Al Omran

6

1

School of Health Policy and Management, York University, 4700 Keele St, Toronto, Canada

2

School of Administrative Studies, York University, 4700 Keele St, Toronto, Canada

3

School of Health Policy and Management, York University, 4700 Keele St, Toronto, Canada

4

ForAHealthyMe.com, Toronto, Canada

5

University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada

6

Vascular Surgery Division, Saint Michael’s Hospital, Toronto, Canada

Keywords: Peripheral Arterial Disease, Chronic Disease Management, eHealth, Health Informatics, Cardiovascular

Disease, Analytics, Virtual Communities, Health Virtual Communities.

Abstract: This paper summarizes the result of a survey conducted on 239 subject in Toronto to gauge their awareness

of Peripheral Arterial Disease (PAD) and educate them about it. The results show that awareness of PAD is

scarce and that the campaign resulted in a significant increase in awareness. This intervention suggest that an

e-education tool is of paramount importance to address the lack of awareness. The paper argues that a PAD

Virtual Community might play a pivotal role in educating the public about PAD and providing a platform for

awareness and prevention.

1 INTRODUCTION

PAD is a condition caused by blockages of the

arteries that provide blood flow to the extremities.

The ankle-brachial index test compares the blood

pressure measured at the ankle, to the blood pressure

measured at the arm. A lower ankle-brachial index

number represents blockages or narrowing of the

arteries. Since PAD is a condition involving

narrowing and blockages of the arteries, an ankle

brachial index test can help recognize its presence

(Kim et al., 2012).

PAD is defined as an ankle-brachial index of less

than 0.9 (Doraiswamy et al., 2009). The ankle

brachial index is the ratio of the blood pressure in the

lower legs to the blood pressure in the arms. The

ankle-brachial index test is a method of measuring an

individual’s risk for peripheral artery disease and is

non-invasive.

Peripheral Arterial Disease (PAD) is an important

public health problem worldwide. It is a widely

prevalent condition affecting 800,000 Canadians, of

which twelve to twenty-nine percent are elderly

(Lovell et al., 2009). It has been estimated that more

than 200 million people were living with PAD

(Fowkes et al., 2013).

The incidence of PAD increases with age and

exposure to the risk factors of atherosclerosis.

However, PAD is given little attention and is referred

as a ‘silent’ cardiovascular disease, with thousands of

Canadians being at risk for preventable heart attacks.

Approximately one-half of all individuals with PAD

are asymptomatic. Studies show that at least one-third

of individuals with asymptomatic PAD, and with at

least one full blockage in a major artery of the leg. In

Canada, the population-based prevalence of PAD has

not been directly assessed. However, approximately

four percent of the population older than forty years

of age in developed nations have PAD (Lovell et al.,

2009).

PAD is a strong indicator of diffuse

atherosclerotic disease; patients have 4 times higher

risk of developing myocardial infarction, and nearly

triple the risk of getting cerebrovascular events

512

Morr, C., Ng, P., Purewal, A., Cole, C., Hamza, M. and Omran, M.

A Health Virtual Community Perspective for Peripheral Arterial Disease - The Need of an E-solution for PAD.

DOI: 10.5220/0005826405120516

In Proceedings of the 9th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2016) - Volume 5: HEALTHINF, pages 512-516

ISBN: 978-989-758-170-0

Copyright

c

2016 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

compared to the general population (Criqui et al.,

1992; Wilterdink and Easton, 1992). In addition,

patients with intermittent claudication, the usual

initial symptom of PAD, have a 5-year morbidity and

mortality of 20-30% from ischemic events of

atherosclerosis, i.e. myocardial infarction and stroke

(Criqui et al., 1992; McDermott, 2002).

PAD is still not well addressed in practice, even

though peripheral arterial disease is simple to detect

and has severe consequences and even though

treating it, or avoiding it, results in significant health

and economic gain (Al-Omran et al., 2006; Al-Omran

et al., 2011; Chow et al., 2008; Criqui, 2001).

In order to (1) raise awareness about PAD in the

Toronto community, (2) measure the level of

awareness of the population about PAD and (3) gauge

the readiness of the population for an Information and

Communication Technology based solution, we have

conducted an intervention that we present its findings

in this paper.

2 THE INTERVENTION

Between September and October 2014 our team has

conducted an awareness campaign in Toronto in 4

different areas of the city that were chosen based on a

convenient sampling approach.

We’ve developed a questionnaire to gauge the

knowledge of a subject on PAD symptoms, risk

factors, preventable measures, treatment modalities

and complications. A total of 239 subject answered a

questionnaire in 3 different areas of Toronto.

The subjects were all asked questions about PAD

and were given an explanation about the disease its

symptoms, risk factors, preventable measures,

treatment modalities and complications. Each subject

was given a score based on her answers. A correct

answer was given one point and an incorrect answer

a zero. We have computed the scores at the baselines

and the scores at follow-up after 6 weeks.

We divided the subjects into two groups

experimental and control. The experimental group

subjects received a pamphlet, the control group

subjects did not. We hypothesized that those who

received a pamphlet will have more retention spam

than those who did not receive one. A follow-up

interview by phone and email was conducted at six

weeks to measure any change in PAD knowledge. In

the follow-up the number of subjects dropped to 76,

38 of which were in the control and 38 in the

experimental.

3 RESULTS

Our convenience sample included 156 female

(65.3%) and 83 male (34.7%) who were interviewed

at three community center and the City Hall.

Most of the subjects (76.1%) were over 41 years

old; 32.2% were 41-60 and 43.9% were over 60 years

old. Only 2.9% were under 20 and 20.9% were

between 21 and 40. It is well known that PAD is

related to age, and our sample did represent the older

age group.

Most of the subject (78.66%) did not hear about

PAD (Figure 1). This confirms a well known fact that

Most Canadians do not know that PAD is a major risk

factor for heart attack, stroke and death (Lovell et al.,

2009)

Figure 1: Subject’s Awareness of PAD.

Most of the subjects were highly educated 90.8% of

the interviewee had a high school or a higher

education degree while 4.2 % attended intermediate

school and 5% attended only primary education

(Figure 2).

Figure 2: Subject’s Education level.

We have used a t-test to test if the difference in scores

between the subjects in the follow-up and their scores

in the baseline. The difference in knowledge scores

was found statistically significant in all 5 aspects of

A Health Virtual Community Perspective for Peripheral Arterial Disease - The Need of an E-solution for PAD

513

PAD between baseline and follow-up for all the 76

subjects. We then tested the significance of change in

scores for each group (experimental and control) for

all the 5 aspect of knowledge. The change was found

to be significant for all 5 aspects in the experimental

group. In the control group that change was only

significant for the knowledge of preventable

measures and treatment modalities.

In terms of questions related to the user’s

readiness in information and communication

technology, the results showed that the younger

population prefer to receive health information via

mobile Apps while elderly prefer usual cell phone and

are wary of Apps. All age groups valued receiving

health information via web pages and email.

In terms of ownership, elderly are prone to have

desktops and laptops more than smartphones iPads

and the like.

High majority of respondents did not appreciate

receiving health information through communication

channels such Facebook, Twitter or YouTube.

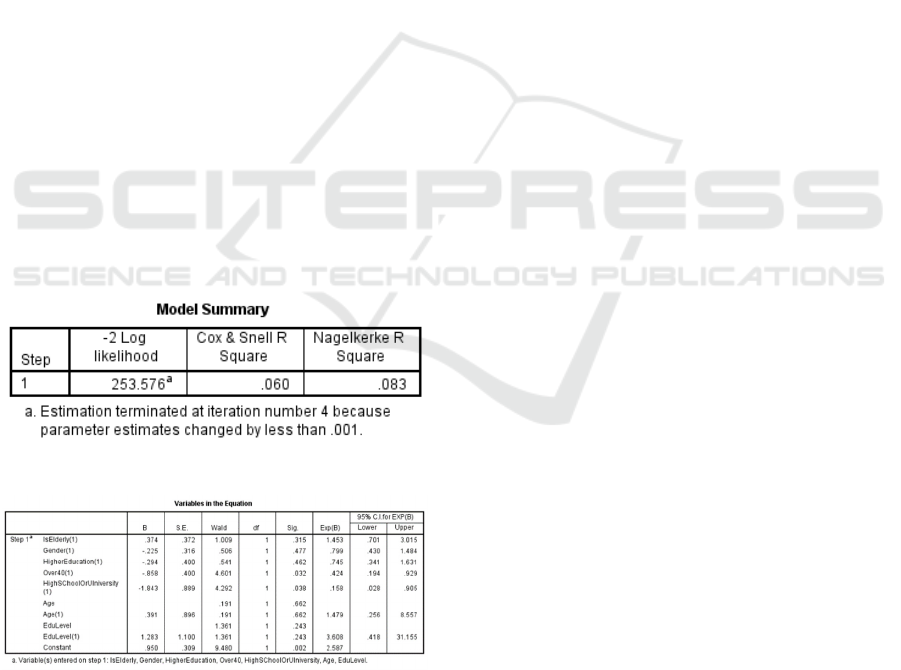

When conducting a logistic regression analysis to

see if age, gender, and education level had an effect

on using a desktop or laptop to connect to the internet,

the analysis showed that both age and the education

level had an effect on the usage of desktops and

laptops. Gender effect was not significant. Being in

the group of people with Age above 40 and people

with Education level high school or university is

significantly correlated with the use of desktops and

laptops to connect to the internet (figure 3 and 4).

Figure 3: Logistic Regression Model Summary.

Figure 4: Logistic Regression Variables.

4 DISCUSSION

The survey showed that a simple intervention with a

simple pamphlet had an effect on the

knowledge/awareness of PAD. The most important is

that even the knowledge of the control group was

enhanced by the simple fact of being exposed to the

verbal explanation during the awareness campaign.

These results suggest that a future e-awareness based

intervention might be more effective and might allow

understand the different characteristics of the people

seeking information and the features that increase the

chance of retention.

On the other hand, since age is a factor affecting

PAD, and people above 40 are correlated with the use

of Desktop and laptops and people above 60 have are

still using cell phones (not smart phones), any

awareness e-tool should take into consideration these

communication channels.

While younger population have a preference

towards Apps; these results were expected. Finally,

less than 5% of all surveyed had preference to

Facebook, Twitter or YouTube, this might indicate

some concerns related to security and confidentiality.

4.1 A Vision of PAD Virtual

Community

A virtual community is a group of people meeting

online to achieve a certain goal, using specific roles

and specific software(Preece, 2000). The concept has

emerged in 1990 with the emergence of the world

wide web. Besides, following the development in the

mobile devices, mobile virtual community were

developed too (El Morr, 2007a, El Morr, 2007b, El

Morr and Kawash, 2007). Soon health related virtual

communities have developed with support to the

healthcare delivery (Gustafson et al., 2001). The

concept of patient centric healthcare delivery

emerged and health virtual community could play an

important role in this field.

Research has demonstrated effectiveness and

efficiency effects linked to VCs for multiple health

conditions (chronic kidney disease, pulmonary

hypertension, cancer) (Bender et al., 2013; El Morr et

al., 2014; Frost et al., 2014; Matura et al., 2013),

especially the engagement of patients in the

management of their own health (Matura et al., 2013;

Vasconcellos-Silva et al., 2013).

A health virtual community for public awareness

of PAD may allow the following advantages over

paper based awareness campaign:

1- It will allow the users to have a tailored and

detailed message that suits the personal

characteristics of the person. For instance, the

information can be communicated using a

language that is most convenient for the potential

HEALTHINF 2016 - 9th International Conference on Health Informatics

514

patient. We have noticed language barrier in a

multicultural city like Toronto. An electronic

delivery system allows the user to choose the

language they want to receive the information.

This is in line with the fact that for example some

immigrant population has a low awareness of

heart disease and stroke (Chow et al., 2008). As a

result, it is possible that PAD is not explained in

the context of different languages and cultures.

2- Besides, the virtual community allows people to

communicate with each other, allowing mutual

support (Welbourne et al., 2013).

3- Virtual Communities proved to be excellent tools

for the evaluation of the physical health status of

a community member, which includes objective

clinical indicators and subjective assessment of

coping ability (Seçkin, 2013). This will allow a

more targeted awareness content and eventually

clinical follow-up.

4- A PAD virtual community will have the

advantage of collecting huge amount of data about

individuals with PAD which constitute a great

source for analytics and new findings.

5- A PAD virtual community allows the content to

be tailored to different delivery channels that suits

the profile of the user (e.g. Apps, web pages, cell

phone short messages). The impact of a tailored

messaging would enhance awareness.

In a PAD virtual community one can allow

patients to receive information and to produce

information (e.g. blood pressure, glucose level in the

blood). Once the healthcare providers receive this

information, they can adjust their treatment or advise

the patients to adjust in a certain way (e.g. life style,

medication).

In a PAD-oriented health virtual community the

PAD awareness would be much more effective and

efficient, having a direct impact on the population

health in terms of prevention or chronic disease

management (Winkelman and Choo, 2003; World

Health Organization, 2005). The economic impact

and social impact would be tremendous.

5 CONCLUSIONS

We conducted a PAD awareness campaign that

measures the knowledge of a sample of the

population in Toronto about PAD as well as their IT

readiness. We followed up the sample after 6 weeks

showed that the experimental group (group that

received a pamphlet) showed significant

enhancement in knowledge of PAD in terms of

symptoms, risk factors, preventable measures,

treatment modalities and complications. We have

observed that even the control group showed

enhanced knowledge in preventable measures and

treatment modalities. It is encouraging that awareness

– even verbally- brings enhanced knowledge in the

preventive measures that can be taken by an

individual.

The sample showed clear preference to the use of

desktop and laptops for browsing internet and

searching for health information. Cell phone was a

mode of communication preferred by elderly. A

Health Virtual Community could have an impact in

the under-served field of PAD and have impact on the

health, social and economic aspects of the disease.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to acknowledge the Ontario Center of

Excellence for funding this study.

REFERENCES

Al-Omran, M., Lindsay, T. F., Major, J., Jawas, A., Leiter,

L. A., Verma, S. and Systematic Assessment of

Vascular Risk, I. (2006) Perceptions of Canadian

vascular surgeons toward pharmacological risk

reduction in patients with peripheral arterial disease.

Ann Vasc Surg, 20(5), pp. 555-63.

Al-Omran, M., Verma, S. and Lindsay, T. F. (2011)

Suboptimal use of risk reduction therapy in peripheral

arterial disease patients at a major teaching hospital.

Ann Saudi Med, 31(4), pp. 371-5.

Bender, J. L., Jimenez-Marroquin, M. C., Ferris, L. E.,

Katz, J. and Jadad, A. R. (2013) Online communities

for breast cancer survivors: a review and analysis of

their characteristics and levels of use. Support Care

Cancer, 21(5), pp. 1253-63.

Chow, C. M., Chu, J. Y., Tu, J. V. and Moe, G. W. (2008)

Lack of awareness of heart disease and stroke among

Chinese Canadians: results of a pilot study of the

Chinese Canadian Cardiovascular Health Project. Can

J Cardiol, 24(8), pp. 623-8.

Criqui, M. H. (2001) Peripheral arterial disease--

epidemiological aspects. Vasc Med, 6(3 Suppl), pp. 3-7.

Criqui, M. H., Langer, R. D., Fronek, A., Feigelson, H. S.,

Klauber, M. R., McCann, T. J. and Browner, D. (1992)

Mortality over a period of 10 years in patients with

peripheral arterial disease. N Engl J Med, 326(6), pp.

381-6.

Doraiswamy, V. A., Giri, J. and Mohler, E. (2009)

Premature peripheral arterial disease – difficult

diagnosis in very early presentation. The International

Journal of Angiology : Official Publication of the

International College of Angiology, Inc, 18(1), pp. 45-47.

A Health Virtual Community Perspective for Peripheral Arterial Disease - The Need of an E-solution for PAD

515

El Morr, C. (2007a) Mobile Virtual Communities. in

Taniar, D., (ed.) Encyclopedia in Mobile Computing &

Commerce: Information Science Reference. pp. 632-

634.

El Morr, C. (2007b) Mobile Virtual Communities in

Healthcare: Managed Self Care on the move. in

International Association of Science and Technology

for Development (IASTED) - Telehealth

(2007),Montreal, Canada.

El Morr, C., Cole, C. and Perl, J. (2014) A Health Virtual

Community for Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease.

Procedia Computer Science, 37, pp. 333–339.

El Morr, C. and Kawash, J. (2007) Mobile Virtual

Communities Research: A Synthesis of Current Trends

and a Look at Future Perspectives. International

Journal for Web Based Communities, 3(4), pp. 386-

403.

Fowkes, F. G., Rudan, D., Rudan, I., Aboyans, V.,

Denenberg, J. O., McDermott, M. M., Norman, P. E.,

Sampson, U. K., Williams, L. J., Mensah, G. A. and

Criqui, M. H. (2013) Comparison of global estimates of

prevalence and risk factors for peripheral artery disease

in 2000 and 2010: a systematic review and analysis.

Lancet, 382(9901), pp. 1329-40.

Frost, J., Vermeulen, E. I. and Beekers, N. (2014)

Anonymity Versus Privacy: Selective Information

Sharing in Online Cancer Communities. J Med Internet

Res, 16(5), pp. e126.

Gustafson, D. H., Hawkins, R. P., Boberg, E. W.,

McTavish, F., Owens, B., Wise, M., Berhe, H. and

Pingree, S. (2001) CHESS: 10 years of research and

development in consumer health informatics for broad

populations, including the underserved. in Patel, V. L.,

Rogers, R. and Haux, R., (eds.) The 10th World

Congress on Medical Informatics (Medinfo

2001),London,UK: IOS Press. pp. 1459-1463.

Kim, E. S., Wattanakit, K. and Gornik, H. L. (2012) Using

the ankle-brachial index to diagnose peripheral artery

disease and assess cardiovascular risk. Cleve Clin J

Med, 79(9), pp. 651-61.

Lovell, M., Harris, K., Forbes, T., Twillman, G., Abramson,

B., Criqui, M. H., Schroeder, P., Mohler, E. R., 3rd and

Hirsch, A. T. (2009) Peripheral arterial disease: lack of

awareness in Canada. Can J Cardiol, 25(1), pp. 39-45.

Matura, L. A., McDonough, A., Aglietti, L. M., Herzog, J.

L. and Gallant, K. A. (2013) A virtual community:

concerns of patients with pulmonary hypertension. Clin

Nurs Res, 22(2), pp. 155-71.

McDermott, M. M. (2002) Peripheral arterial disease:

epidemiology and drug therapy. Am J Geriatr Cardiol,

11(4), pp. 258-66.

Preece, J. (2000) Online Communities: Designing Usability

supporting Sociability, USA:

John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Seçkin, G. (2013) Satisfaction with health status among

cyber patients: testing a mediation model of electronic

coping support. Behaviour & Information Technology,

32(1), pp. 91-101.

Vasconcellos-Silva, P. R., Carvalho, D. and Lucena, C.

(2013) Word Frequency and Content Analysis

Approach to Identify Demand Patterns in a Virtual

Community of Carriers of Hepatitis C. Interactive

Journal of Medical Research, 2(2), pp. e12.

Welbourne, J. L., Blanchard, A. L. and Wadsworth, M. B.

(2013) Motivations in virtual health communities and

their relationship to community, connectedness and

stress. Comput. Hum. Behav., 29(1), pp. 129-139.

Wilterdink, J. L. and Easton, J. D. (1992) Vascular event

rates in patients with atherosclerotic cerebrovascular

disease. Arch Neurol, 49(8), pp. 857-63.

Winkelman, W. J. and Choo, C. W. (2003) Provider-

sponsored virtual communities for chronic patients:

improving health outcomes through organizational

patient-centred knowledge management. Health

Expectations, 6(4), pp. 352-358.

World Health Organization (2005) Preventing Chronic

Disease: A Vital Investment. Geneva, Switzerland:

World Health Organization (WHO).

HEALTHINF 2016 - 9th International Conference on Health Informatics

516