Older Adults, Learning and Technology

An Exploration of Tangible Interaction and Multimodal Representation of

Information

Emma Murphy

Higher Education Research Centre and School of Computing, Dublin City University, Dublin, Ireland

Keywords: Ageing, Technology, Older Adults, Learning, Universal Design for Learning, Tangible Interaction.

Abstract: This paper explores concepts of tangible interaction and multimodal representation of information framed

by the theories of universal design for learning (UDL) to enhance learning for older adults. Two

participatory user panels were organised to explore the potential of assistive technology and tangible

interaction to engage and support older learners. A creative co-design method using a rich user scenario

with practical demonstration examples was used. Existing assistive technologies designed for users with

visual impairments and a novel design prototype were presented to participants. This design prototype is

based on the idea of linking physical fixed learning materials with digital multimodal representations.

Feedback on the existing and new interactive tools are presented based on the reactions and ideas of 7 older

adult students between the ages of 57 and 76. Participants were not familiar with examples of assistive

technology such as screenreaders and magnification, but were interested in exploring new ways to have

information represented through multiple modalities for learning.

1 INTRODUCTION

When asked what active ageing means to them, the

majority of older adults tend to think in terms of

physical health and activity (Bowling 2008; Stenner

et al., 2011). The Active Ageing Policy Framework,

states that “active ageing is the process of

optimizing opportunities for health, participation and

security in order to enhance quality of life as people

age” (WHO, 2002). Importantly the word “active”

has been further clarified by the WHO as referring to

“continuing participation in social, economic,

cultural, spiritual and civic affairs, not just the

ability to be physically active or to participate in the

labour force.” (WHO, 2002).

There is considerable evidence to show that the

various aspects of active ageing are intertwined and

that it is important to take a holistic, interdisciplinary

approach rather than looking at each aspect in

isolation. For example a growing body of literature

posits a connection between engagement in

education as an adult and associated ‘wider’

benefits, including health (Schuller and Watson,

2009; Findsen and Formosa, 2011; Field, 2011). As

a further recognition of the importance of education,

the active ageing policy has recently been revised

and enriched with additional pillar of lifelong

learning (ILC, 2015).

This is reflected in the rapidly growing

participation of older adults in formal and informal

learning sectors. According to Cruce and Hillman

(2012) higher education institutions have been slow

to respond to these demographic changes due to the

lack of empirical information regarding the

educational preferences of older adults. Furthermore

sensory, physical, cognitive impairments associated

with the ageing process hinder initial involvement as

current higher education learning infrastructures are

designed for a younger student population.

1.1 Older Adults, Learning and

Technology

Studies have illustrated that older adults generally

have positive opinions and attitudes about trying and

using new technology (Mitzner et al., 2010). But we

must also acknowledge that sensory, physical and

cognitive impairments associated with the ageing

process can hinder older users’ perceptions and

experiences when interacting with technology

(Zajicek, 2001; Fisk, 2009), especially if no

attention has been paid to principles of inclusive

Murphy, E.

Older Adults, Learning and Technology - An Exploration of Tangible Interaction and Multimodal Representation of Information.

In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2016) - Volume 1, pages 359-367

ISBN: 978-989-758-179-3

Copyright

c

2016 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

359

design (Clarkson, 2003). Heart and Kalderon (2011)

highlight that health status is a moderating factor for

computer use and digital literacy. Therefore older

adults with illness or disability, the cohort who are

often the intended beneficiaries of digital

technologies, are likely to have the most difficulty

using them.

The rapid rate of technical change will always

present challenges to new users of all ages. Once a

user has learned a new technology, an even newer

version often becomes available. Already the

definition of digital literacy has evolved in terms of

the tools and skills required. For example,

technology classes for older adults that are based in

a desktop learning environment may not be relevant

or necessary for the tasks and end goals of older

students. In order to learn to communicate, share

files and participate online, it is no longer necessary

to understand file structures, software and operating

systems that still form a core component of many

digital literacy classes. Alternative approaches to

digital literacy using touchscreen tablets and mobile

phones are arguably more accessible and relevant to

older students (Doyle, 2011).

New innovations as part of the Internet of Things

and tangible interaction, where interfaces are

embedded into everyday objects, will again redefine

what it means to be digitally literate. So when we

think about older adult learners and technology we

need to move beyond providing digital literacy skills

alone. Rather we need to think about sustainable

strategies where technology can enhance learning

and participation. Without taking away from the

value of digital literacy perhaps if we shift the focus

to how technology can support learning we might

end up with digital literacy as a by-product of

learning another subject or skill. The flexible use of

technology as proposed in Universal Design for

Learning could be a more progressive way to

consider learning and technology for older adults.

1.2 Universal Design for Learning

Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is a

framework for understanding how to create curricula

and resources that meet the needs of all learners

from the start rather than retrofitting accessible

solutions (Rose and Meyer, 2002). UDL is based

upon the most widely replicated finding in

educational research: learners are highly variable in

the way that they perceive and comprehend

information Rose and Strangman, 2007). For

example, those with sensory disabilities (e.g.,

blindness or deafness); cognitive disabilities (e.g.,

dyslexia, dementia); language or cultural

differences, require different ways of accessing

content.

Universal design for Learning (UDL) proposes

“Learning is most effective when it is multimodal -

when material is presented in multiple forms.

Students benefit from having multiple means of

accessing and interacting with material and

demonstrating their knowledge through evaluation.”

(Rose and Strangman, 2007).

(Rose and Meyer, 2002) highlight that the

flexible features of digital media offer an ideal

foundation for the UDL framework in comparison to

traditional fixed materials such as printed textbooks.

The ability to provide multiple forms of

representation using technology and make

information flexible hold great potential for the

groups of adult learners that have taken part in this

study. Furthermore Lee et al. (2009) investigated the

potential beneficial effect of the presentation of

multimodal (as opposed to unimodal) sensory

feedback on older adults’ performance on a touch

screen device. Results of this study clearly show that

both objective and subjective measures of older

users’ performance were enhanced by the

presentation multimodal feedback.

1.2.1 UDL and Existing Accessibility

Features

Accessibility tools such as Voiceover and Apple’s

built in screen magnifier Zoom have been designed

to specifically support users with visual

impairments. Such accessibility solutions could

potentially give the flexibility to overcome many of

the barriers faced by older adult learners due to

sensory and cognitive issues experienced. However

the potential of features such as screen readers and

magnifiers with support older student’s learning has

not previously been explored.

The multiple forms of representation and

expression proposed in universal design for learning

can be implemented easily using tools such as

Apple’s Voiceover to present information visually

through text and also through speech. Findings from

interviews with older students revealed that most

learners were unfamiliar with existing assistive

technology even though the majority of participants

reported mild to moderate vision impairments

(Murphy, 2015). One of the aims of this present

study was to introduce assistive technology to older

students to explore their perceptions and reactions.

CSEDU 2016 - 8th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

360

1.2.2 Tangible Interaction and Multimodal

Notes Prototype

Older learners have developed strategies and

relationships with fixed traditional materials such as

printed books, handwritten notes and diagrams and

can be reluctant to swap those strategies for new

digital tools (Murphy, 2015). A significant number

of participants in student interviews reported anxiety

with regard to memory loss particularly in the

context of formal learning and preparing for exams.

Anxiety related to memory and learning is a

significant issue as it affects confidence and stress

levels which in turn can have a negative effect if any

memory impairment is present (Peavy et al, 2009).

While participants were positive about the benefits

of technology as an information resource and

method for organization, they also showed a striking

preference for hand written notes during lectures and

in preparation for exams. While learners of different

ages also benefit from handwritten physical notes

they display a higher and more integrated use of

mobile devices and laptops for learning on and off

campus (Chen, B., deNoyelles, 2013; Gikas and

Grant, 2013).

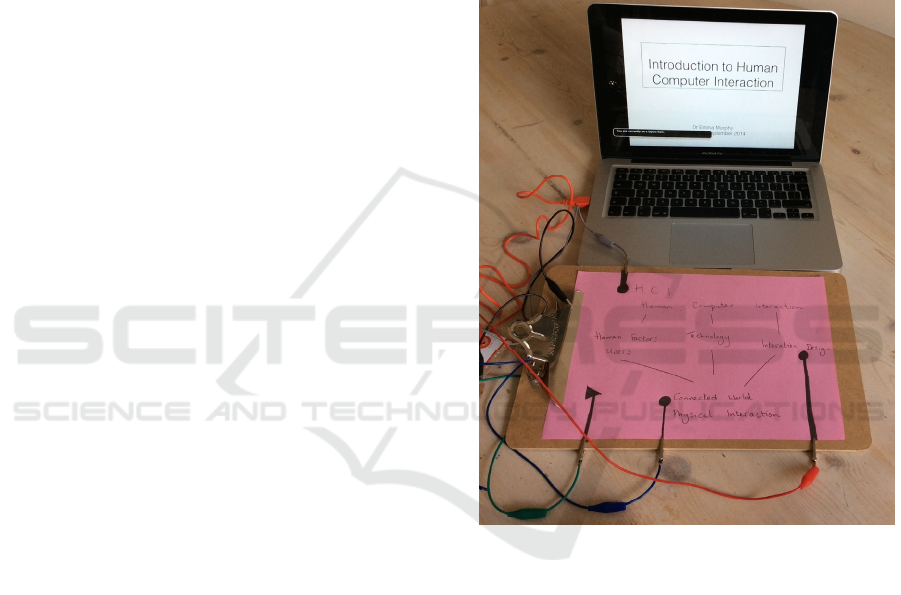

There is great potential in the application of

tangible user interface design to explore this design

challenge. Recent advances in the design of tangible

interface toolkits as part of the maker movement has

made embedded computing more accessible. MaKey

MaKey is a printed circuit board that can send key

presses, mouse clicks, and mouse movements from

every day physical objects to a computer (Silver et

al., 2012) (see figure 1 and also figure 2, example of

banana piano created with MaKey MaKey).

A design possibility with this tangible interaction

toolkit is the potential to use physical drawings in

lead pencil as a controller. Figure 1 illustrates an

example of physical notes as a controller for a

detailed interactive presentation with text and video

and screen reader. The intention is to link both

intelligent digital systems and familiar strategies and

physical tools (such as handwritten notes) that older

adults rely on for learning.

This multimodal notes design idea is intended to

support memory by extending the use of handwritten

notes by linking them with more detailed and

flexible digital representations. In addition to

providing multiple means of representation this use

of multimodal tangible interaction for learning also

extends to the UDL principle for multiple means of

action and expression (National Center on Universal

Design for Learning, 2012). This is particularly

important for older adults who may have multiple

sensory, physical or cognitive age related

impairments.

Furthermore by creating familiar controllers

through fixed learning materials (such as pen and

paper) older learners might be more willing to use

existing accessibility tools such as screen readers

and magnifiers so that they can process the

information through their preferred modality or

multiple modalities. The intention is to link both

intelligent digital systems and familiar strategies and

physical tools (such as handwritten notes) that older

adults currently rely on for learning.

Figure 1: Multimodal Notes Design Prototype.

2 METHODS

2.1 User Panels with Older Students

User panels were organised based on the creative

group work format presented in [8]. This method can

be summarized as a participatory design method

based around a rich use scenario. Lively characters

are created at the centre of the scenario to engage

users and the scenario is punctuated with interactive

elements and demonstrations in the modality that is

being designed. In this design method, the purpose

of the use scenario is not to cover all possible usages

of an application or technology or indeed all

possible users. The purpose of the scenario is to

Older Adults, Learning and Technology - An Exploration of Tangible Interaction and Multimodal Representation of Information

361

trigger creative design ideas and user reactions while

maintaining the discussion on a certain context and

user character. Gaps occur at appropriate points in

the story, replacing user interface elements where

user feedback is required (Pirhonen and Murphy,

2008). The incorporation of tangible interaction

design examples built using MaKey MaKey

enhances the creative element of this method.

Furthermore Rogers et al. successfully demonstrated

the benefits of using this toolkit with groups of older

adult users as a catalyst for creative and inventive

participatory design (Rogers et al., 2014).

2.2 Purpose of the Study

The aim of the user panels with older students was

to explore the following areas:

1. To explore older students’ reactions to existing

accessibility technologies such as screen

readers and magnifiers by demonstrating

practical examples (Apple Voiceover and

Zoom Magnification).

2. To explore participants’ reactions to the

potential to link fixed learning materials with

digital media by presenting the Multimodal

Notes Prototype.

3. To explore the next steps for the design of the

multimodal notes prototype or other interfaces

that use tangible interaction for learning.

2.3 User Panel Participants

7 older students took part in the user panels between

the ages of 57 and 76 (AV= 68; SD= 6.7). Three

students formed the first panel and four students

participated in the second session. Students were

asked to complete a short questionnaire to elicit

details on age, gender, field of study and age related

impairments in hearing, sight, manual dexterity,

physical health and cognitive issues (results are

presented in table 1).

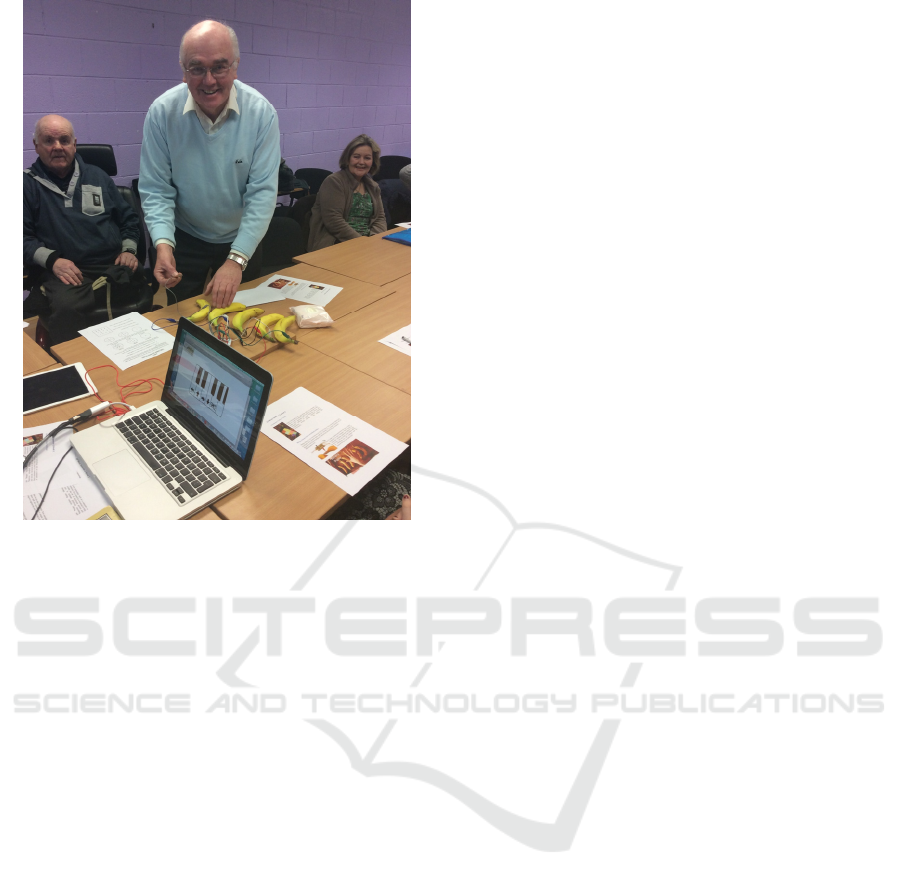

Students were invited to participate in user panel

sessions lasting approximately 90 minutes. Every

attempt was made to create an informal relaxed

setting to make participants comfortable.

Participants were seated around a table and

tea/coffee and refreshments were served. Each panel

began with informal discussion, an introduction to

the study and informed consent. As a warm up

exercise and to explore the idea of multimodal

interaction users tried out a banana piano made

using MaKey Makey (as illustrated in Figure 2).

This exercise also aimed to generate a fun creative

atmosphere while also introducing the idea of and

potential of tangible interaction.

A rich use scenario was created based on

findings from interview data with 18 older students

(Murphy, 2015). The scenario described a character,

studying Philosophy at the age of 68 and had issues

with her vision, mild hearing loss, and anxiety about

her memory decline. During the scenario there were

pauses to demonstrate and discuss technology

Table 1: User panel participant details.

Participant ID Age Gender Type of Study Self Reported Age Related

Impairments

User Panel 1

Participant 1 74 Female

Recently completed undergraduate

degree (currently in informal

learning course on campus)

Sight issues, glasses for reading,

Mild Memory loss

Participant 2 76 Female Informal learning on campus Glasses for Reading

Participant 3 57 Male 1

st

Year Undergraduate Mild memory loss

User Panel 2

Participant 4 64 Female Informal Learning on campus

Moderate sight issues, wears

glasses all the time; hearing,

tinnitus an issue in crowds

Participant 5 64 Female Informal Learning on campus No reported issues

Participant 6 63 Female 4

th

Year Undergraduate Mild Memory Loss and Anxiety

Participant 7 70 Male 1

st

Year Undergraduate

Moderate hearing loss in one ear;

glasses for reading; manual

dexterity issues due to arthritis

CSEDU 2016 - 8th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

362

Figure 2: Photo of music student trying out a “banana

piano” created using MaKey MaKey.

examples. The final section of the scenario described

the issues related to the relationships between fixed

learning materials such as hand written notes and

flashcards and the multimodal representations of

digital content. The design example used MaKey

MaKey to link notes to a multimodal presentation

with screen reader and video was presented to the

participants. For both sessions the discussion

focused the content of the scenario and the older

learner character, using open ended questions to

focus the discussion.

The following is an extract from the scenario and

highlights the way that the technology was

demonstrated as part of the scenario:

Molly woke early to the sound of her alarm, today

was the last day of lectures before the end of year

exams. ……She had begun her Philosophy degree at

the age of 68 and was now in her second year of

fulltime study……Her eyesight was not what it once

was but with her varifocal glasses she generally had

no trouble walking around and reading print but

screens indoors and outdoors could still be a

problem. ….As she had been having trouble reading

the notes on her laptop screen, her personal tutor

had put her in touch with the technology department

who had shown her how to use a screen reader

[show example of a screen reader, pass around

iPads for participants to try]. Molly was intrigued

although she was not sure how she felt about turning

on and off the screen reader it seemed complicated.

…but she was also very attached to her methods of

handwritten notes, translated slowly down to

flashcards using shorthand, keywords and diagrams

to trigger her memory for longer texts and

explanations. What if there was some way of

combining the wealth of information on her

computer with speech and her familiar handwritten

notes? [Demonstrate multimodal notes prototype]

The facilitator read the user scenario pausing at each

technology or interaction example to demonstrate

and ask participants to interact with the tools for

themselves. After each example participants were

asked for their feedback and initial reactions to the

accessibility tools and multimodal prototype.

2.4 User Panel 1 Main Findings and

Quotes

2.4.1 Feedback on Existing Accessibility

Tools on the Apple iPad

When participants in the first user panel were shown

the screen reader as part of the scenario, they were

surprised that the technology existed and had not

heard of it previously. The voice speed was set to 50

percent and all participants in the first panel

immediately reacted to the speed saying it was too

fast to understand. Participant 1 compared the screen

reader to audiotapes of written texts which she used

extensively when she was studying previously:

“I used them an awful lot…..you could walk the

beach and pick up every word” P1

Participants acknowledged that the voice was not as

natural as an audio tape but appreciated that it had

“an Irish accent” and once it was slowed down felt

that they would like to use it.

“The voice is fine if you can slow it down” P1

“Yes I’d find if you are tired you could switch [the

screen reader] on….reading is tiring, after reading

maybe 100 pages you are just exhausted after

it…that [screen reader] would definitely be of

benefit to me]”P3

Participant 3 was very positive about integrating

the screen reader into his learning but he did raise

one issue regarding language that using the screen

reader you may listen more passively and be less

likely to stop reading to look up a word or a concept

that you were unsure of. However if you could

control the screen reader to highlight a word and

look it up this would not be an issue.

Older Adults, Learning and Technology - An Exploration of Tangible Interaction and Multimodal Representation of Information

363

“The only thing I would say [with] academic

language ..sometimes there’s words you’d never

heard of and it would be great if you come across a

word like that you could double tap…show me

dictionary or something like that” P3

Participants in the first user panel had a very

positive reaction to the features on the iPad for low

vision users. They particularly liked the Zoom

feature that allows users to move a magnified

window around the screen like a physical

magnifying glass.

Participant 1 liked way method of navigation

using the window to move around the screen:

“This magnifying is brilliant…when you start to use

the computer you are very awkward…with that you

hold to it…and move right and left….I think for

older people that would make all the difference” P1

All three students felt it was difficult to figure out

how to turn on and off accessibility settings.

Although there are ways to create shortcuts to turn

on and off accessibility features, all 3 participants

agreed that they would like a voice command to turn

the features on and off. Participant 2 felt that she

would not explore the accessibility features in the

settings section of the iPad.

“What does accessibility say to you?....you wouldn’t

go into any of those buttons [settings menu] unless

somebody said to you if you want to make it easier

this is what you do”P2

Participant 1 agreed that she would be hesitant to

explore the accessibility functions on an iPad or

other device:

“If there was an “undo” button you might

investigate it more…I think with all of these extras

you would have to be computer literate to use all of

them…you just have to tip a button and the screen

changes completely. .and then you have to get it

back to the way it was” P1

2.4.2 Multimodal Notes Prototype

In their reaction to prototype multimodal notes

demonstration, participants in the first user panel

saw a benefit for this idea for revising for exams.

They considered that having the physical controls as

part of the written mind map would help to

memorise larger amounts of information that you

could listen or look at.

“For older people I think it is great because really

all you have is words when you go into an exam and

you have to build around it.”P1

“I rely on mind maps..get your keywords

down..some way of that interacting with that

[computer]” P3

Participant 3 suggested that the combination of

physical interaction and multimodal presentation of

information might speed up the memory process.

“Rote learning…it still works..I just read it over 4

times…[the multimodal learning tool could be ] a

way of maybe speeding that process up..” P3

Participant 2 agreed that exploring the information

using the mixture of physical presentation, sound

and images could benefit your memory.

“You need an icon or a keyword to jog your

memory.. bringing it up like this. reinforcing the

keywords...even listening to it without having to look

at it..is memorizing it for you rather than having to

look at it…it’s another way” P2

2.5 User Panel 2 Main Findings and

Quotes

2.5.1 Feedback on Existing Accessibility

Tools on the Apple iPad

Similar to the first user panel, participants were

initially struck by the speed of the screen reader:

“I don’t think I could keep up with that…”P7

“She speaks very fast!....I don’t even know what she

is saying it’s just garbage!”P6

After slowing down the screen reader to 20 percent,

participant 6 felt that it was not slow enough to

understand the article.

“I’d have to have it slower now….it’s academia so

the wording is very [important]” P6

However when the screen reader was set to it’s

lowest level at 0 percent participant 6 did not like

the quality of the voice at the lowest speed.

“She sounds so sad!. .no I’d have to get rid of that

voice” P6

Participant 5 appreciated the fact that you could

adjust the speed of the speech unlike an audio book.

“That’s very good that you can slow it down to

whatever pace you like, that’s a plus for it.” P5

For participant 7, the screen reader reminded him of

the voice of the GPS system he used in his car and

he considered that he would use a screen reader for

learning in the same way as an option to not use the

screen.

“I like the sound. .I would compare it to the GPS

that I have in the car.. I always like the voice on that

means you don’t have to look at it…that is what I am

CSEDU 2016 - 8th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

364

comparing [the screen reader] with….in the same

way I could read the screen but the voice is

helpful….It’s [the screen reader] actually very good,

I wasn’t aware of that now” P7

All users agreed voice activation would be their

preferred way to turn on and off the screen reader.

There was full consensus in the second panel that the

screen magnifier was a useful tool

“They are wonderful [referring to low vision

features]” P6

2.5.2 Multimodal Notes Prototype

The section in the scenario that referred to the

character’s anxiety regarding memory triggered a

lively discussion among participants in the second

user panel confirming the relevance of memory and

anxiety and how that can affect exam performance.

Participant 7 spoke in detail about how he has used

mind maps to overcome his memory and confidence

issues for learning and revising for exams and he

questioned the value of the prototype for exam

preparation. He was concerned that having

interactive digital material linked to the physical

mind map could create a false sense of knowledge

which would not be available in an exam.

“Are you substituting technology for memory?”P7

However participant 6 recognised the value of

the multimodal presentation of information lined to

the physical mind map:

“You know the way there are different forms of

learning like there is visual and that...so is that

[design prototype] covering all forms of learning

[for] your memory” P6

Participant 5 also agreed that the multimodal

presentation would help her to retain information.

In terms of developing this multimodal notes

idea, participants questioned the process of

organising the information and identified that this

was an important missing element in the design of

the tool. The group agreed that the information

would have to be in a digital format to begin with

which could be an issue for certain academic

courses. But importantly the organisation of the

multimodal material for learning or memorising had

to be individualised to the student to suit their need,

which would change according to content and

circumstance. With regard to linking the digital

content to the physical mind map, participants in the

second panel considered this a useful idea.

Participant 7 had an interesting observation in

that he considered this tool would be more useful for

ongoing learning and continuous assessment rather

than as a memory enhancing tool for an exam

situation as proposed by the first panel. Rather than

beginning with the mind map and using it to link to

lengthier and interactive content he proposed that

you could work the opposite way. In his idea you

should begin with the interactive content and reduce

it to the more sparse mind map and then use it as a

memory tool. For participant 7 the usefulness of the

tool would depend on the supporting application that

could arrange the various interactive elements

including the accessibility tools on the

computer/digital device. Participant 6 agreed that

this way of working could be beneficial to

structuring though and ideas for academic essay

writing and continuous learning and assessment.

3 DISCUSSION

In an attempt to create new interactions and designs

for older students it is interesting that existing

accessibility solutions (such as screen readers and

magnifiers) are so underused by a group that could

benefit from applications designed to support

physical and sensory impairments. None of the

participants in the users panels had ever tried a

screen reader or magnifier or even heard of related

assistive technology. While participants were very

interested in trying out the screenreader, certain

elements such as the rapid pace do not make it an

inclusive tool for older adults. Furthermore the

accessibility features on the iPad were considered

“hidden” by the older students as they were not

aware of them and considered the process of turning

features on and off cumbersome. The option to have

an obvious “undo” feature for any learning tool was

valued by the group. The process of finding the

screenreader and magnifier tools on the iPad were

not considered straightforward by participants.

Furthermore they did not relate to the word

“Accessibility” which links to the suite of tools.

These are important findings for the designers of

assistive technology particularly when they are

striving for universal access.

Participants were enthusiastic about the

possibilities of using physical handwritten notes to

control digital multimodal representations. There

was interesting discussion in both panels as to how

the prototype could be developed and whether it

should be a tool to aid continuous learning or as a

memory enhancing tool to help prepare for exams.

Participants recognised the need and value of

presenting information in different and sometimes

Older Adults, Learning and Technology - An Exploration of Tangible Interaction and Multimodal Representation of Information

365

multiple modalities. They felt that this should be

controlled by the learner according to their

individual learning preference or impairment. From

this feedback there is great potential to link existing

accessibility features into an inclusive learning tool

that focused on multiple representations and

interactions with media and information. But also it

highlights the relevance of Universal Design for

Learning for older students and the importance of

providing information through multiple modalities.

The rich use scenario successfully conveyed the

wider context of use of how assistive technology

tools and the new prototype idea might support a

learner. Participants engaged and empathised with

the character in the scenario through verbal and

nonverbal agreement as the facilitator read the

scenario. The section of the scenario regarding

memory and learning were particularly relevant to

participants’ own learning experiences.

While participants tried out the physical

controllers using MaKey MaKey they did not build

their own controllers or interfaces. This would be

interesting to have more of a workshop style to the

next panel as proposed in (Rogers et al, 2014). The

ideas and feedback generated by both user panels are

extremely valuable for the design of the next

iteration of the proposed learning tool. The next

design panel will have more of a practical creative

element to try to explore the area of tangible

interaction in more detail.

4 CONCLUSIONS

This interdisciplinary research is an exploration of

the potential of UDL and interaction design to create

inclusive representations of information to support

older adult learners. Previous interviews with older

students revealed that learners have strong

connections and strategies with traditional fixed

learning materials but are also open to trying out

new technologies. A prototype multimodal learning

tool was created and presented to 2 panels of older

students to elicit their feedback and creative ideas

for the next iteration of the design. Feedback from

the group has revealed that there is potential in

linking physical learning strategies and materials to

flexible digital representations of information and to

existing accessibility solutions. The next stage of

this design will continue to involve older students as

co-designers to create a software tool and to explore

more creative ideas in relation to tangible interaction

and learning.

It is also hoped that as this research will

highlight the potential of engaging older students

with technology to support the wider context of their

learning and enable them to overcome barriers due

to age related sensory, physical or cognitive

impairments. Rather than associating older adults,

learning and technology with digital literacy skills

alone, this approach focuses on novel ways to

engage students in lifelong learning supported by

creative and interactive technology.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research is supported by the Irish Research

Council (www.research.ie). I would also like to

thank all participants for their time, enthusiasm and

valuable input.

REFERENCES

Bowling, A. (2008). Enhancing later life: how older

people perceive active ageing? Aging and Mental

Health, 12, 3, 293-301.

Chen, B., deNoyelles, A. (2013). Exploring students’

mobile learning practices in higher education.

Educause Review Online. Retrieved from http://

www.educause.edu/ero/article/exploring-students-

mobile-learning-practices-higher-education.

Clarkson, J., Coleman, R., Keates, S. and Lebbon C, (eds.)

(2003), Inclusive Design: Design for the Whole

Population. (London: Springer-Verlag).

Cruce, Ty M., Hillman, Nicholas W (2012) Preparing for

the Silver Tsunami: The Demand for Higher

Education Among Older Adults, Research in Higher

Education (2012) 53: 593-613.

Doyle, Julie. (2011) iPad Classes at GNH. Available

http://www.netwellcasala.org/ipad-classes-at-gnh.

Field, J, (2011) Researching the benefits of learning: the

persuasive power of longitudinal studies, London

Review of Education, 9(3), 283-292.

Findsen, B., Formosa, M., (2011) Lifelong Learning in

Later Life: A Handbook on Older Adult Learning,

Sense Publishers, Rotterdam.

Gikas, J., Grant, M. M. (2013). Mobile computing devices

in higher education: Student perspectives on learning

with cellphones, smartphones & social media. The

Internet and Higher Education, 19, 18-26.

Heart, T and Kalderon, E. (2011) Older adults: Are they

ready to adopt health-related ICT?", International

Journal of Medical Informatics, 82(11), pp.1 -23.

International Longevity Centre Brazil (2015). Active

Ageing: A Policy Framework in Response to the

Longevity Revolution. Rio de Janeiro. ILC-Brazil.

Jenkins, A, (2011), ‘Participation in Learning and

Wellbeing Among Older Adults’, International Journal

of Lifelong Education, 30:3, 403-420.

CSEDU 2016 - 8th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

366

Lee, J., Poliakoff, E., Spence, C. (2009) The Effect of

Multimodal Feedback Presented via a Touch Screen

on the Performance of Older Adults. HAID 2009: 128-

135.

Mitzner, T. L., Boron, J. B., Fausset, C. B., et al. (2010).

Older adults talk technology: Technology usage and

attitudes. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(6), 1710-

1721.

Murphy, E. (2015) An Exploration of UDL and Interaction

Design to Enhance the Experiences of Older Adult

Learners in Proceedings of AHEAD Universal Design

for Learning: A License to Learn, Dublin Castle,

March 19-20.

National Center on Universal Design for Learning. (2012).

UDL Guidelines – Version 2.0: Principle I. Provide

Multiple Means of Representation http://

www.udlcenter.org/aboutudl/udlguidelines/principle1.

Peavy, G. M.; Salmon, D. P.; Jacobson, M. W.; Hervey,

A.; Gamst, A. C.; Wolfson, T.; Patterson, T. L.;

Goldman, S.; Mills, P. J.; Khandrika, S.; Galasko, D.

(2009). Effects of Chronic Stress on Memory Decline

in Cognitively Normal and Mildly Impaired Older

Adults. American Journal of Psychiatry 166 (12):

1384–1391.

Pirhonen, A., Murphy, E., (2008) Designing for the

Unexpected: The role of creative group work for

emerging interaction design paradigms Journal of

Visual Communication Special Issue on Haptic

Interactions, 7(3) 331-344.

Rose, D. and Strangman, N. (2007). Universal Design for

Learning: meeting the challenge of individual learning

differences through a neurocognitive perspective.

Universal Access in the Information Society, 5:381-

391.

Rose, D. H., & Meyer, A. (2002). Teaching every student

in the digital age: Universal Design for Learning.

Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and

Curriculum Development.

Schuller, T., & Watson, D. (2009). Learning through life.

Leicester: NIACE.

Silver, J., Rosenbaum, E. and David Shaw. (2012) Makey

Makey: improvising tangible and nature-based user

interfaces. In Proceedings of the Sixth International

Conference on Tangible, Embedded and Embodied

Interaction (TEI '12), Stephen N. Spencer (Ed.). ACM,

New York, NY, USA, 367-370.

Rogers, Y., Paay, J., Brereton, M., Vaisutis, K., Marsden,

G.,Vetere. F. (2014) Never too old: engaging retired

people inventing the future with MaKey MaKey. In

Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human

Factors in Computing Systems (CHI '14). ACM, New

York, NY, USA.

Stenner, P., McFarquhar, T., Bowling, A. (2011) Older

people and “active ageing”: subjective aspects of

ageing actively, Journal of Health Psychology, vol. 16,

no. 3, 467–477.

WHO (2002) Active Ageing A Policy Framework.

Available: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/

67215/1/WHO_NMH_NPH_02.8.pdf [Accessed: 27

October 2015].

Zajicek, M. (2001). Interface design for older adults. In R.

Heller, J. Jorge, and R. Guedj (Eds.), Proceedings of

the 2001 EC/NSF workshop on Universal accessibility

of ubiquitous computing: providing for the elderly (pp.

60-65). New York: ACM.

Older Adults, Learning and Technology - An Exploration of Tangible Interaction and Multimodal Representation of Information

367