Collateral Damage of Online Social Network Applications

Iraklis Symeonidis

1

, Pagona Tsormpatzoudi

2

and Bart Preneel

1

1

KU Leuven, ESAT/COSIC and iMinds, Leuven-Heverlee, Belgium

2

ICRI/CIR, KU Leuven and iMinds, Leuven, Belgium

Keywords:

Online Social Networks, Applications, Facebook, Privacy by Design, Privacy Risk.

Abstract:

Third party application providers in Online Social Networks can collect personal data of users through their

friends without the user’s awareness. In some cases, one or more application providers may own several

applications and thus the same provider may collect an excessive amount of personal data, which creates

a serious privacy risk. Previous research has developed methods to quantify privacy risks in Online Social

Networks. However, most of the existing work does not focus on the issues of personal data disclosure via

the user’s friends applications and application providers. The aim of this paper is to investigate the need for

solutions that can compute privacy risk related to applications and application providers. In this work we

perform a legal and technical analysis of the privacy threats stemming from the collection of personal data

by third parties when applications are installed by the user’s friends. Particularly, we examine the case of

Facebook as it is the most popular Online Social Network nowadays.

1 INTRODUCTION

Online Social Networks (OSNs) have altered the so-

cial ecosystem in a remarkable way. OSNs supports

a plethora of applications (Apps) providing games,

lifestyle and entertainment opportunities developed

by third parties. Such Apps may disclose a user’s per-

sonal data from their online friends to third party ap-

plication providers (AppPs) (Chaabane et al., 2012;

McCarthy, 2014). In some cases, AppPs may own

several Apps, through which they may get access to

larger amounts of personal data. As a consequence,

personal data disclosure may pose significant privacy

risks and prompts serious concerns among the users,

the media and the research community (Consumerre-

ports, 2012; Krishnamurthy and Wills, 2008; Wang

et al., 2011).

When a user shares information with her online

friends in OSNs the user is not aware whether a

friend has installed Apps that may access her personal

data. Moreover, she is not aware that her personal

data are further exposed to the AppPs. We define as

collateral damage the privacy issues that arise by:

(1) the acquisition of users’ personal data by the Apps

installed by a user’s friends, (2) the acquisition of per-

sonal data of a user by the AppPs, who may disclose

this data outside the OSN ecosystem.

From a legal point of view, these privacy issues

cause concerns with respect to data protection leg-

islation. Data protection law provides a framework

for the protection of the users’ fundamental rights and

in particular the right to privacy during processing of

personal data. Personal data, pursuant to Article 2(a)

of the Data Protection Directive 95/46/EC (95/46/EC,

2015) “refers to any information relating to an iden-

tified or identifiable natural person (i.e., user)” which

in the scope of this paper corresponds to the user’s

measurable personal data processed by the App. Data

protection law may be infringed in relation with two

aspects: (1) data processing lacks legitimacy as the

user has not given her consent to the App processing

her personal data, and (2) data processing lacks trans-

parency as the user may be totally unaware of the data

processing that may take place.

There exists a considerable amount of related

work regarding the user’s privacy in OSNs, includ-

ing work that investigates installed Apps (Bicz

´

ok and

Chia, 2013; Chaabane et al., 2012; Chia et al., 2012;

Huber et al., 2013). However, there is no prior work

analyzing the case where a set of AppPs collects the

user’s personal data via the Apps installed by the

user’s friends. Moreover, there is no work that esti-

mates the privacy risk of the users in the case of the

collateral damage of the Apps in OSNs.

Based on the assumption of privacy as a good

practice (Diaz and G

¨

urses, 2012), our research is

536

Symeonidis, I., Tsormpatzoudi, P. and Preneel, B.

Collateral Damage of Online Social Network Applications.

DOI: 10.5220/0005806705360541

In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy (ICISSP 2016), pages 536-541

ISBN: 978-989-758-167-0

Copyright

c

2016 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

motivated by the need to reduce the collateral

damage of the Apps in OSNs. Technically, we study

how an evaluation of the privacy risk can help the user

to better manage her privacy. We define the privacy

score of a user as an indicator of her privacy risk. The

higher the privacy score, the higher the threat to the

user. A privacy risk computation is a Privacy Enhanc-

ing Technology. Privacy Enhancing Technologies are

able to raise awareness on personal data collection

and may support the user’s decisions about personal

data sharing (Nicol

´

as et al., 2015). From a legal point

of view, our solution aims to implement transparency

following the principle of Data Protection by Default.

Data Protection by Default was introduced in Arti-

cle 23 (2) of the draft Data Protection Regulation,

which requires mechanisms that, “by default ensure

that the users are able to control the distribution of

their personal data” (Parliament, 2015). Data protec-

tion by default intends to mitigate privacy risks stem-

ming from users’ asymmetrical information (Nicol

´

as

et al., 2015). In the context of this paper, data pro-

tection solutions, such as privacy score, raise user’s

awareness and enhance her empowerment.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Sec-

tion 2 reviews the related work with respect to the

privacy issues that Apps introduce in OSNs as well

as the existing research related to the user’s privacy

risk. Section 3 describes the case of Facebook OSN.

Section 4 concludes and proposes the future work.

2 RELATED WORK

This section describes the related work on privacy is-

sues that arise from the use of Apps in OSNs. More-

over, it describes the existing work on the computa-

tion of privacy risk in OSNs.

Currently there exists work related to the privacy

issues of Apps in OSNs. Chaabane et al. (Chaa-

bane et al., 2012) showed that the Apps can have

tracking capabilities and disseminate the collected in-

formation to “fourth party” organizations (Chaabane

et al., 2014). Similarly, Huber et al. developed an

automatic evaluation tool, AppInspect (Huber et al.,

2013), and demonstrated security and privacy leak-

ages of a large set of Facebook Apps. Furthermore,

Bicz

´

ok and Chia (Bicz

´

ok and Chia, 2013) described

the issue of users’ information leaked through their

friends via Apps on Facebook. This work introduced

a game theoretic approach to simulate an interdepen-

dent privacy scenario of two users and one App game.

Extending the work of Bicz

´

ok and Chia (Bicz

´

ok and

Chia, 2013) Pu and Grossklags (Pu and Grossklags,

2014) proposed a formula to estimate the payoffs. Fi-

nally, Frank et al. (Frank et al., 2012) showed the exis-

tence of malicious Apps that deviate from the generic

permissions pattern acquiring more information from

the users, while Chia et al. (Chia et al., 2012) showed

that certain Apps collect more information than nec-

essary.

To estimate the privacy risk for a user, Maximi-

lien et al. (Maximilien et al., 2009) initially proposed

a Privacy–as–a–Service formula. This formula is used

to compute the privacy risk as the product of sensitiv-

ity and visibility of personal data. Liu and Terzi (Liu

and Terzi, 2010) extended this work (Maximilien

et al., 2009) and proposed a framework for comput-

ing the privacy risk using a probabilistic model based

on the Item Response Theory (IRT). Although, IRT

presents interesting results to compute the sensitivity

of the user’s personal data, there is a lack of evalua-

tion for the visibility. Moreover, S

´

anchez and Viejo

(S

´

anchez and Viejo, 2015) developed a formula to

asses the sensitivity of unstructured textual data, such

as wall posts in OSNs. Their model aims to control

the dissemination of the user’s data to different recip-

ients of an OSN (Viejo and S

´

anchez, 2015). Minkus

et al. (Minkus and Memon, 2014) estimated the sen-

sitivity and visibility of the privacy settings based

on a survey of 189 participants. Finally, Nepali and

Wang (Nepali and Wang, 2013) proposed a privacy in-

dex to evaluate the inference attacks as described by

Sweeney (Sweeney, 2000), while Ngoc et al. (Ngoc

et al., 2010) introduced a metric to estimate the poten-

tial leakage of private information from public posts

in OSNs.

To the best of our knowledge, there is currently

no work that considers the case of the collateral dam-

age of the Apps for computing the privacy risk. The

existing related work is mainly focused on estimat-

ing a privacy score as an impact on the dissemination

of the user’s information to the other members of an

OSN. Our work is focused on the privacy impact that

arises from the acquisition of users’ personal data via

the Apps installed by the user’s friends and the user

itself. These Apps expose the user’s personal data

to the AppPs, outside the OSN ecosystem, without

users’ prior knowledge.

3 THE CASE OF FACEBOOK

APPLICATIONS

This section analyses the collateral damage pri-

vacy issues of the Apps for the case of Facebook.

Facebook is a popular OSN with more than 1.4 bil-

lion monthly active users (Statista, 2015).

Facebook offers a plethora of easy–to–use tools

Collateral Damage of Online Social Network Applications

537

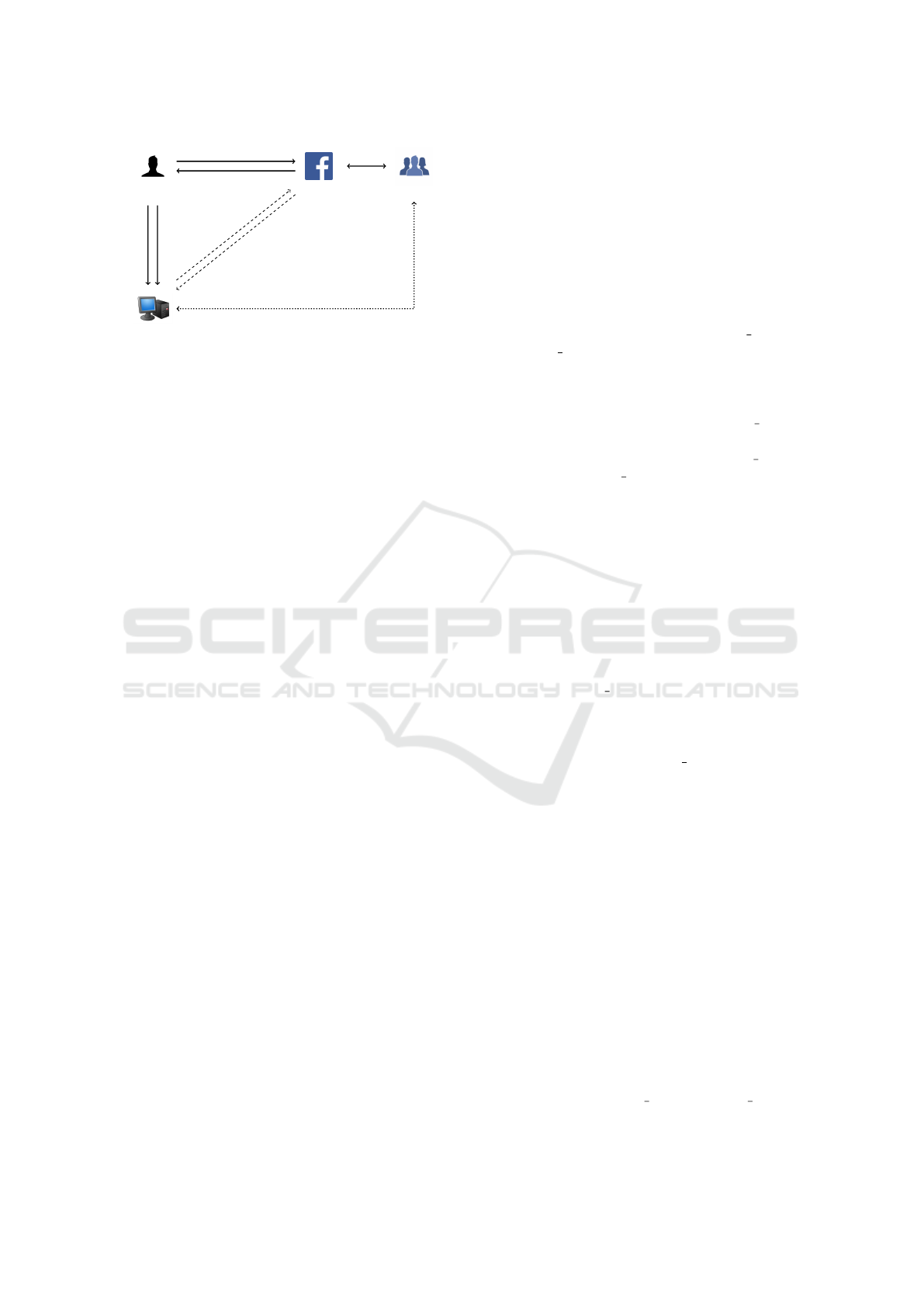

User

User’s Friends

Application Server

Facebook

1. Get App & Allow permissions

2. Authenticate to access Application

4. Run Application

3. Give Access Token for Permissions

5. Get Access Token

6. Send User Information

Figure 1: Facebook applications architecture overview.

such as Apps developed by third party application

providers (AppPs). Currently, there are over 25, 000

Apps available on Facebook (Huber et al., 2013; SBA-

Research, 2015). Users on Facebook are able to

construct online profiles (Boyd and Ellison, 2008).

A user’s profile consists of information that can be

stored with the aim to be shared with other entities

such as other users and Apps. For instance, on Face-

book there is a list of more than twenty attributes in

a user’s profile, such as “age”, “birthday”, “gender”,

and “location” (Facebook, 2015).

A running App can retrieve information from a

user’s profile; this information can subsequently be

accessed and stored by the AppPs. For an App to ac-

cess the user’s profile, an installation process has to

be performed. Each App requests from the user a set

of permissions, that allow the App to access and col-

lect additional information. This is done by an access

token provided by Facebook, that requires authoriza-

tion from the user (steps 1 to 4 in Figure 1). After

the user’s approval, Apps can collect the user’s per-

sonal data and store these data at the AppPs servers.

Therefore, the user’s personal data are stored outside

the Facebook ecosystem and out of the user’s control

(steps 5 and 6 in Figure 1).

In order to control the visibility of the user’s per-

sonal data, Facebook offers a set of privacy settings to

its users. The set of available privacy settings (Face-

book, 2015) is broad, and it ranges from restricted to

public, with settings such as “only me”, “friends”,

“friends to friends”, “custom” and “public”. For

the case of Apps on Facebook, the privacy setting

“only me” restricts the visibility of the personal data

to the user. However, privacy settings of “friends”,

“friends of friends”, “custom” and “public” equally

expose the user’s personal data to third party AppPs

via their friends’ Apps, making them available to ex-

ternal servers.

Moreover, due to the server–to–server communi-

cation (steps 5 and 6 in Figure 1), the offline interac-

tion between Facebook and AppPs makes any protec-

tion mechanisms hard to apply (Enck et al., 2014). As

a result, the user’s profile information can arbitrarily

be retrieved by AppPs without notification or approval

of the user.

3.1 Users’ Information is Exposed by

their Friends

Initially, the API v.1 of Facebook provided a set of

permissions to the Apps, such as f riends birthday,

and f riends location. Those permissions gave the

AppPs the right to access and collect users’ per-

sonal data via their friends, such as the user’s birth-

day and location. However, currently the Facebook

API version v.1 is obsolete and the f riends xxx per-

missions are not present. The updated API version

v.2 (Facebook, 2015) replaced the f riends xxx per-

missions with the user f riends. Although the newer

API had to be in line with the regulations of EU

and U.S. (95/46/EC, 2015; FTC, 2015), our analysis

showed that it discloses up to fourteen user attributes

via the user’s friends; maintaining the privacy con-

cerns of collateral damage of the Apps as an open

problem. A more detailed view on the available per-

missions of Apps is given in Table 3 in the Appendix.

Furthermore, Apps can request permissions

through strangers (non–friends) who participated in

the same conversation group with the user (i.e., per-

sonal messages). This is the case, for instance, for

the permission read mailbox. The mere exchange of

text messages in a group conversation may disclose

user personal data: when the user participates in a

group conversation with other users (friends and non–

friends) who has installed read mailbox, the user’s

personal data becomes accessible to the Apps. This

personal data can be the content of the conversation as

well as the time that the communication took place.

To examine the problem, we performed an anal-

ysis of the Apps on Facebook. We used the pub-

licly available dataset provided by Hubert et al (Hu-

ber et al., 2013; SBA-Research, 2015). The dataset

consists of 16, 808 Facebook applications between

2012 and 2014. It contains the application name, id,

number of active users (daily, weekly and monthly),

the requested permissions and the Apps that an AppP

owns. For this paper we analyzed the permissions of

Apps with more than 10, 000 Monthly Active Users

(MAU). Among, these Apps we identified the pro-

portion of permissions that cause the collateral

damage privacy issue. Moreover, in order to calculate

the number of personal data that Apps can collect we

considered the number of corresponding permissions

to that data such as friends photos and user photos to

photos.

ICISSP 2016 - 2nd International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

538

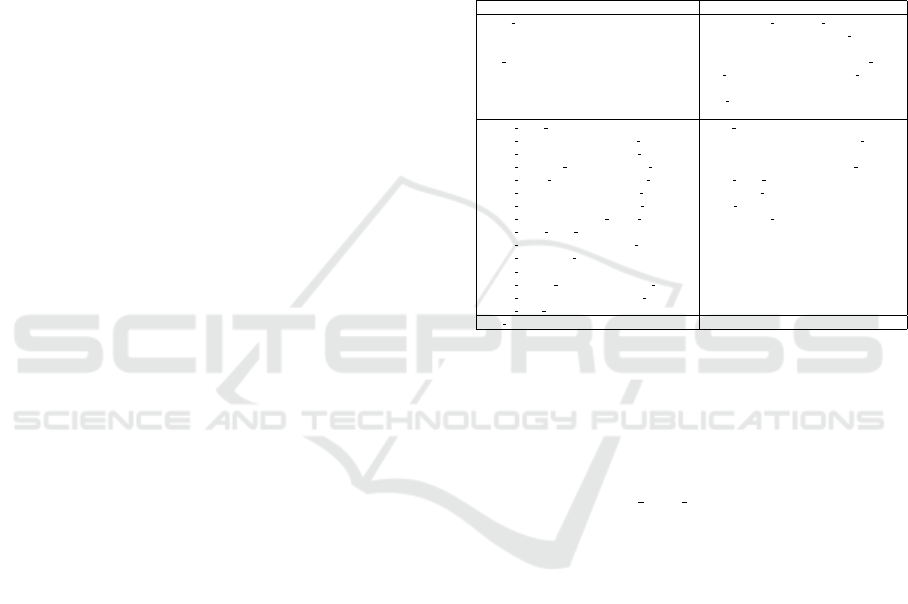

Table 1: Facebook most requested permissions for more

than 100 and 10, 000 Monthly Active Users.

Permissions ≥ 100 Monthly ≥ 10 000 Monthly

email 50.5 % 61.8 %

user birthday 19.4 % 24.5 %

user likes 14.1 % 12.8 %

user location 7.3 % 7.9 %

publish actions 31.1 % 50.3 %

publish stream 31.4 % 19.3 %

user photos 10.6 % 8.5 %

friends xxx 10.23% 10%

read mailbox 0.9% 0.45%

From the list of 16, 808 Apps on Facebook, we

identified 2, 200 Apps with more than 10, 000 monthly

active users (MAU). As described in Table 1, we ver-

ified that several Apps request permissions for col-

lecting sensitive data, such as birthday 28.7%, pho-

tos 12.9%, likes 14.8%, location 9.5%, friend infor-

mation 10.23%, and, more invasive, private mailbox

privileges 0.45%. Among this sensitive data the most

commonly requested friends related permissions for

the Apps that enable the collateral damage issue,

were friends

birthday 4.2%, friends photos 4.4%,

friends likes 1.8% and friends location 1.5%.

While the permissions affecting friends’ data

seem limited, the lack of transparency and opt–out

option (lack of consent) for the user is worrisome.

Moreover, although read mailbox appears to be used

by only 0.45% of the Apps the severity of the risks it

may entail for the user is significant.

3.2 Third Party Application Providers

Third party application providers (AppPs) can be

owners of several Apps. As a consequence, one AppP

may collect through those Apps several personal data

items of each user. The amount of personal data that

can be retrieved is equal to the collection of all the ac-

quired personal data under the same AppP. Moreover,

every App retrieves the Facebook’s user ID which can

identify a user and can be used to accurately correlate

the collected personal data from each App. For in-

stance, extending our analysis for the AppPs we iden-

tified that there are AppPs with up to 160 Apps with

more than 10, 000 MAU (see Table 2). Moreover,

we repeated our analysis for the Apps and its corre-

sponding AppPs that enable the collateral damage

problem. We identified that “Astrologix” and “Social

sweethearts GmbH” AppPs have 7 Apps and ”Shine-

zone” 5.

3.3 Legal Issues

From a legal perspective, one of the main challenges

of data protection attached to the Apps permissions,

Table 2: Facebook application providers and the amount

of its corresponding applications for more than 100 and

10, 000 Monthly Active Users.

Application Provider ≥ 100 Monthly ≥ 10, 000 Monthly

Vipo Komunikacijos 163 99

Telaxo 136 118

Mindjolt 120 32

superplay! 81 8

as described above, is the fact that personal data pro-

cessing may lack legitimacy. Article 7 of Data Pro-

tection Directive 1995/46/EC (95/46/EC, 2015) pro-

vides a limited number of legal grounds aiming to

perform personal data processing, such as the “the

user’s unambiguous consent”. As enshrined in Ar-

ticle 7a, the data controller, i.e., Facebook or Apps,

may collect, store, use and further disclose the data, if

the user has given her consent. For the consent to be

valid, it has to fulfil certain criteria: it has to be given

prior to the data processing, accepted in a “free” way

and sufficiently specified and informed (Art. 29 WP

2011) (95/46/EC, 2015).

However, Facebook third party Apps can proceed

to the users personal data processing only with the

user’s friends’ consent. In other words, consent may

be provided only by the user of the App and not by

the user, whose data however will be processed in the

end. On Facebook Apps settings, users allow by de-

fault their data to be used by their friends Apps, unless

they manually uncheck the relevant boxes “Apps other

use”. One could claim that consent has been theoret-

ically given. However, the U.S. Federal Trade Com-

mission required that Apps cannot imply consent, but

this should be rather affirmatively expressed by the

users. Despite this requirement, due to the default pri-

vacy setting on Facebook, users are totally unaware of

the fact that they have to uncheck the boxes in order

to prevent such data processing (FTC, 2015).

Further, with regards to the obligation of the

data controller (Facebook or Apps) to transparency, it

should be noted that in both cases, users have neither

sufficient information about the nature and amount of

data that will be collected nor about the purposes that

the data will be used for. In other words data process-

ing goes far beyond the user’s legitimate expectations.

This interferes with the principle of fairness and trans-

parency stemming from Article 10 of Data Protection

Directive 46/1995/EC (95/46/EC, 2015). In relation

with the same matter, the U.S. Federal Trade Com-

mission stressed the need to keep users informed in

case any disclosure exceeds the restrictions imposed

by the privacy setting(s) of the Apps (FTC, 2015).

This can be possibly the case of permissions such as

user friends.

Collateral Damage of Online Social Network Applications

539

4 CONCLUSION AND FUTURE

WORK

In this paper, we analyse the importance of the privacy

issues that arise from the collection of the user’s per-

sonal data that can be collected by third party Apps

installed by the user’s friends in OSNs. Moreover,

we analyse the case where Apps under a minor set

of AppPs can collect the users’ personal data and

expose them outside of the OSN ecosystem without

prior knowledge of the users. To demonstrate the im-

portance of the problem we analyzed the case of the

Facebook Apps.

Considering the privacy issues that arise from the

installation of third party Apps, this paper performs a

privacy risk assessment which is in line with the legal

principle of privacy by default. It aims to illustrate

how the user’s data disclosure takes place through

the acquisition of users’ personal data via Apps in-

stalled by their friends in OSNs. A calculation of a

user’s privacy risk can be useful to both users and re-

searchers. A privacy risk assessment (Nebel et al.,

2013) can help the privacy-aware users to better sup-

port their decisions when they install Apps. The in-

crease of awareness on personal data collection is in

line with the legal principle of data protection by de-

fault, as it can potentially support decisions and foster

user control on personal data disclosure. From the re-

searchers’ perspective, a numerical value describing

the user’s information exposure would allow statisti-

cal inferences and comparisons for better privacy de-

sign.

A previous work proposed by Liu and Terzi (Liu

and Terzi, 2010; Maximilien et al., 2009) developed

a 2–dimensional matrix to compute the privacy risk,

considering the sensitivity and the visibility of a user’s

personal data to the users of an OSN. Our future work

aims to extend this model also to Apps and AppPs.

Moreover, our analysis considers the Apps and AppPs

that are available at the time of writing. However,

since API and Apps are rapidly evolving it would be

interesting to update and extend the current dataset

with the recent Apps available on Facebook.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I notably want to thank Dr. Markus Hubert and SBA

Research center for providing us with the necessary

material for our study. A thank you to Andrea Di

Maria, Dalal Azizy, Dr. Danai Symeonidou, Prof.

Gergely Bicz

´

ok, Dr. Mustafa A. Mustafa, Fateme Shi-

razi, Dr. Filipe Beato and all the anonymous review-

ers who helped to better shape the idea and the quality

of the text. This work was supported in part by the

Research Council KU Leuven: C16/15/058.

APPENDIX

Table 3 illustrates the permissions available for the

API v.1 and v.2 respectively.

Table 3: Facebook application permissions and the corre-

sponding personal data. Permission availability to API v.1

¬ and v.2 .

Permissions Personal data

public profile¬ id, name, first name, last name, link, gen-

der, locale, timezone, updated time, veri-

fied

user friends¬ bio, birthday, education, first name,

last name, gender, interested in, lan-

guages, location, political, relation-

ship status, religion, quotes, website,

work,

friends about me¬,

friends actions¬, friends activities¬,

friends birthday¬ friends checkins¬,

friends education history¬, friends events¬,

friends games activity¬, friends groups¬,

friends hometown¬, friends interests¬,

friends likes¬, friends location¬,

friends notes¬, friends online presence¬,

friends photo video tags¬,

friends photos¬, friends questions¬,

friends relationship details¬,

friends relationships¬,

friends religion politics¬, friends status¬,

friends subscriptions¬, friends website¬,

friends work history¬

about me, actions, activities, birthday

checkins, history, events, games activity,

groups, hometown, interests, likes,

location, notes, online presence,

photo video tags, photos, questions,

relationship details, relationships, re-

ligion politics, status, subscriptions,

website, work history

read mailbox¬ inbox

REFERENCES

95/46/EC (Accessed April 15, 2015). Directive 95/46/ec

of the european parliament and of the council.

http://ec.europa.eu/justice/policies/privacy/docs/95-

46-ce/dir1995-46 part1 en.pdf.

Bicz

´

ok, G. and Chia, P. H. (2013). Interdependent privacy:

Let me share your data. In Financial Cryptography

and Data Security - 17th International Conference,

FC 2013, Okinawa, Japan, April 1-5, 2013, Revised

Selected Papers, pages 338–353.

Boyd, D. and Ellison, N. (2008). Social Network Sites:

Definition, History, and Scholarship. Journal of

Computer-Mediated Communication, 13(1).

Chaabane, A., Ding, Y., Dey, R., Ali Kaafar, M., and Ross,

K. (2014). A Closer Look at Third-Party OSN Ap-

plications: Are They Leaking Your Personal Informa-

tion? In Passive and Active Measurement conference

(2014), Los Angeles,

´

Etats-Unis. Springer.

Chaabane, A., Kaafar, M. A., and Boreli, R. (2012). Big

friend is watching you: Analyzing online social net-

works tracking capabilities. WOSN ’12, pages 7–12,

New York, NY, USA. ACM.

Chia, P. H., Yamamoto, Y., and Asokan, N. (2012). Is this

app safe? A large scale study on application permis-

sions and risk signals. In WWW, Lyon, France. ACM.

Consumerreports (Accessed on Sept. 6, 2012). Facebook

and your privacy: Who sees the data you share on the

biggest social network? http://bit.ly/1lWhqWt.

ICISSP 2016 - 2nd International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

540

Diaz, C. and G

¨

urses, S. (2012). Understanding the land-

scape of privacy technologies. Proc. of the Informa-

tion Security Summit, pages 58–63.

Enck, W., Gilbert, P., Chun, B., Cox, L. P., Jung, J., Mc-

Daniel, P., and Sheth, A. (2014). Taintdroid: an

information flow tracking system for real-time pri-

vacy monitoring on smartphones. Commun. ACM,

57(3):99–106.

Facebook (Accessed February 08, 2015). Face-

book privacy settings and 3rd parties.

https://developers.facebook.com/docs/graph-

api/reference/user/.

Frank, M., Dong, B., Felt, A., and Song, D. (2012). Min-

ing permission request patterns from android and face-

book applications. In ICDM, pages 870–875.

FTC (Accessed February 08, 2015). FTC and Face-

book agreement for 3rd parties wrt privacy set-

tings. http://www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/ docu-

ments/cases/2011/11/111129facebookagree.pdf.

Huber, M., Mulazzani, M., Schrittwieser, S., and Weippl,

E. R. (2013). Appinspect: large-scale evaluation of

social networking apps. In Conference on Online So-

cial Networks, COSN’13, Boston, MA, USA, October

7-8, 2013, pages 143–154.

Krishnamurthy, B. and Wills, C. E. (2008). Characterizing

privacy in online social networks. WOSN ’08, pages

37–42, New York, NY, USA. ACM.

Liu, K. and Terzi, E. (2010). A framework for computing

the privacy scores of users in online social networks.

TKDD, 5(1):6.

Maximilien, E. M., Grandison, T., Liu, K., Sun, T., Richard-

son, D., and Guo, S. (2009). Enabling privacy as a

fundamental construct for social networks. In Pro-

ceedings IEEE CSE’09, 12th IEEE International Con-

ference on Computational Science and Engineering,

August 29-31, 2009, Vancouver, BC, Canada, pages

1015–1020.

McCarthy, C. (Accessed Apr. 9, 2014). Under-

standing what Facebook apps really know (FAQ).

http://cnet.co/1k85Fys.

Minkus, T. and Memon, N. (2014). On a scale from 1 to

10, how private are you? Scoring Facebook privacy

settings. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Usable

Security (USEC 2014). Internet Society.

Nebel, M., Buchmann, J., Ronagel, A., Shirazi, F., Simo,

H., and Waidner, M. (2013). Personal information

dashboard: Putting the individual back in control.

Digital Enlightenment.

Nepali, R. K. and Wang, Y. (2013). SONET: A social net-

work model for privacy monitoring and ranking. In

33rd International Conference on Distributed Com-

puting Systems Workshops (ICDCS 2013 Workshops),

Philadelphia, PA, USA, 8-11 July, 2013, pages 162–

166.

Ngoc, T. H., Echizen, I., Komei, K., and Yoshiura, H.

(2010). New approach to quantification of privacy on

social network sites. In Advanced Information Net-

working and Applications (AINA), 2010 24th IEEE In-

ternational Conference on, pages 556–564. IEEE.

Nicol

´

as, N. M., Carmela, T., Pagona, T., Fanny, C., and

Daniel, L. M. (Accessed May 04, 2015). “Deliverable

5.1 : State-of-play: Current practices and solutions.”

FP7 PRIPARE project. http://pripareproject.eu/wp-

content/uploads/2013/11/D5.1.pdf.

Parliament, E. (Accessed May 04, 2015). Euro-

pean parliament legislative resolution of 12

march 2014 on the proposal for a regulation.

http://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getDoc.do?

pbRef=-//EP//TEXT+TA+P7-TA-2014-

0212+0+DOC+XML+V0//EN.

Pu, Y. and Grossklags, J. (2014). An economic model and

simulation results of app adoption decisions on net-

works with interdependent privacy consequences. In

Decision and Game Theory for Security - 5th Interna-

tional Conference, GameSec 2014, Los Angeles, CA,

USA, November 6-7, 2014. Proceedings, pages 246–

265.

S

´

anchez, D. and Viejo, A. (2015). Privacy risk assessment

of textual publications in social networks. In Loiseau,

S., Filipe, J., Duval, B., and van den Herik, H. J., edi-

tors, ICAART (1), pages 236–241. SciTePress.

SBA-Research (Accessed Sept 09, 2015). Appinspect: A

framework for automated security and privacy anal-

ysis of osn application ecosystems. http://ai.sba-

research.org/.

Statista (Accessed Sept 09, 2015). Leading so-

cial networks worldwide as of august 2015,

ranked by number of active users (in millions).

http://www.statista.com/statistics/272014/global-

social-networks-ranked-by-number-of-users/.

Sweeney, L. (2000). Simple demographics often identify

people uniquely. Health (San Francisco), 671:1–34.

Viejo, A. and S

´

anchez, D. (2015). Enforcing transpar-

ent access to private content in social networks by

means of automatic sanitization. Expert Syst. Appl.,

42(23):9366–9378.

Wang, Y., Komanduri, S., Leon, P., Norcie, G., Acquisti, A.,

and Cranor, L. (2011). I regretted the minute I pressed

share: A qualitative study of regrets on Facebook. In

SOUPS.

Collateral Damage of Online Social Network Applications

541