Effectiveness of an Instructional Intervention in Developing

Critical Thinking Skills

Role of Argument Mapping in Facilitating Learning of Critical Thinking Skills

Shumaila Mahmood

Southampton Education School, University of Southampton, University Rd, So17 1bj, Southampton, U.K.

Keywords: Critical Thinking Skills, Cognitive Load Theory, Argument Mapping, Instructional Interventions, Cognitive

Tools, Learning and Instruction, Visualization Tools.

Abstract: This paper is focused on how argument mapping (AM) software can be helpful for developing critical

thinking (CT) skills of initial teacher educators. The study discusses the usefulness of argument mapping

software for lessening the cognitive load of students. The main study is conducted to test the effectiveness

of an instructional intervention for the development of critical thinking skills. The effectiveness includes an

assessment of the implementation process as well. The instructional intervention is comprised of computer

supported (audio-video lectures and argument mapping) and non-computer supported (Communities of

Inquiry discussions and concept mapping on paper) learning materials thought to enhance the CT skills of

initial teacher educators in a public teacher education university in Pakistan. The teaching programme based

on seven principles has several elements for teaching critical thinking of which one is computer supported

visual representation (argument mapping). In this paper, the focus is on participants’ accounts of the

usefulness of visual representation (argument mapping) feature for the provision of critical thinking. The

analysis shows the positive influence of computer-supported argument mapping in increasing student

interest in learning CT. However, the belief that argument mapping increases critical thinking could not be

determined in this study for design issues. Students found that AM help them lessening cognitive load while

helping in structuring thoughts. The results from observations and interview responses are discussed for the

implications of argument mapping in mainstream teaching at college/university level with regards to

teaching critical thinking skills. The paper briefly discusses the possibility of placing cognitive load theory

on instructional interventions explains a lot about complex learning environments, element interactivity and

learning. Therefore, if rightly executed, visualization tools as part of teaching strategies for CT may increase

the critical thinking skills.

1 INTRODUCTION

This study’s intention is to improve the quality of

classroom teaching and learning in postgraduate

teacher education programs in a public teacher

education institution. The objectives of this study are

1) an emphasis on a mixed (explicit and embedded)

intervention (Ennis, 1991; Abrami et al., 2008)

implementation approach such as to investigate the

extent that the intervention is effective or not, 2) to

obtain real classroom data about how critical

thinking skills instructional intervention elements

are implemented meaning what happens in an actual

classroom environment. This paper focuses on the

importance and role of visualization tools as part of

CT instructional interventions. This study focuses on

the role of visualization tools, cognitive load theory

and argument maps in assisting the critical thinking

intervention design primarily related to lessen

extraneous (the way information or tasks are

presented) and germane (the work put into creating a

schema) cognitive load (Paas, Renkl and Sweller,

2003) of the learners.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Cognitive Load and Learning of

Critical Thinking

Cognitive load is the amount of effort that an

330

Mahmood, S.

Effectiveness of an Instructional Inter vention in Developing Critical Thinking Skills - Role of Argument Mapping in Facilitating Learning of Critical Thinking Skills.

In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2016) - Volume 1, pages 330-336

ISBN: 978-989-758-179-3

Copyright

c

2016 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

activity poses on working memory at a point in time

(Moody, 2004). Cognitive load theory is well known

for explaining cognitive processes and instructional

designs. Its importance is known for improving

speed and accuracy of understanding and deep

understanding of information content (Moody, 2004).

At the same time, it considers the structure of

information and the cognitive architecture that

allows to understand and learning, learner and

instructional designs interactions. This allows for a

unique opportunity to understand complex learning

schemas, the role of working memory, long term

memory and why some materials are difficult to

learn and many more (Paas et al., 2003; Cooper,

1998). There an extensive amount of work available

from Sweller, 1988; 1994; 1999, Paas et al., 2004,

Paas and Ayres, 2014 Nonetheless, cognitive load

theory is not void of flaws and counter arguments

about its usability and correctness for example see

Moreno (2010) and De Jong (2010).

2.2 Cognitive Modelling Tools

Cognitive tools by definition are tools, means or

instruments that are used to improve the cognitive

powers of learners during their thinking, problem-

solving and learning (Jonassen et al., 1997; Pea,

1985; Salomon, Perkins and Globerson, 1991).

According to Derry and Lajoie (1993, p. 5) “the

appropriate role for a computer system is not that of

a teacher/expert, but rather, that of a mind-extension

cognitive tool” or what Jonassen (1994;1995) calls

mind tools. Cognitive tools, according to Derry and

Lajoie (1993) are unintelligent tools, relying on the

learner to provide the intelligence. To lever this need

of visualising complex thought processes,

technology proves handy to support human

cognition with a range of interfaces available (Lajoie

and Derry, 2013). Cognitive tools are categorised

into two main sections cognitive teaching strategies

(non-computer based) and cognitive modelling tools

(computer based). This section discusses methods of

reasoning, judgement, problem solving, procedures

and processes of cognitive activity that help in

learning high order thinking skills.

2.2.1 Concept Mapping

Concept mapping is a visual technique to organize

information. It is presented in the form of nodes that

are connected to circles or boxes; the relationship

among concepts is usually depicted with a

connecting line (Novak 2004; Novak and Cañas,

2006). Kim and Olaciregui (2008) used concept

maps in learning activity that employed reviewing

and increasing concept map based information. Liu,

Chen and Chang (2010) investigated effectiveness of

concept maps as an aid in improving English reading

comprehension. More recently Adesope and Nesbit

(2013) used concept mapping for improving

narrative reading. Studies have also shown concept

maps helpful in increasing student achievement

(Chiou, 2008). Lim, Lee and Grabowski (2009)

established concept maps as effective instructional

tools. They found students with high self-regulated

skills gained more than those of with low self-

regulated skills.

In another study by Cheema & Mirza (2013) the

effects of concept mapping on academic

achievement has been studied. These tools are seen

to be effective in improving students’ performance

in general science. The study also observed that the

effects of concept mapping are positively related

with academic achievement. Tan (2012) focuses on

using Intel thinking Tools for the development of

critical thinking skills of twenty teacher trainees.

The results reveal an increase in the trainees’ critical

thinking abilities in completing their assignments..

This implies that concept maps may work better

with adult students to promote meaningful learning

(Horton et. al., 1993) who will learn to use the

software and meaning and use of boxes, symbols

faster than young children. Buehl and Fives (2011)

also shows effectiveness of concept maps in the

discipline of Educational Psychology as instructional

assessment tool.

2.2.2 Argument Mapping

According to van Gelder (2013), argument mapping

(AM) has been prepared with the explicit intention

of decreasing the mental load and to facilitate

learning and development of critical thinking skills.

Harrell (2008; 2011) researched over the

effectiveness of visual representation for the

development of critical thinking skills. The

researcher used argument mapping within the

context of an introductory philosophy course. The

results of the study showed improvements in the

critical thinking skills of students. In order to make

argument mapping successful, students must be

taught how to construct argument diagrams to aid in

the understanding and evaluation of the arguments.

The writer considers diagram mapping useful for

developing general CT skills and discipline specific

analytic abilities both. Dwyer, Hogan, and Stewart

(2010; 2012; 2013) examined the effects of critical

thinking in an e-learning course. The course was

Effectiveness of an Instructional Intervention in Developing Critical Thinking Skills - Role of Argument Mapping in Facilitating Learning of

Critical Thinking Skills

331

taught through argument mapping in the discipline

of psychology. The study follows a quantitative

approach using quasi-experimental methods.

3 METHODOLOGY

3.1 Research Study Design

A sequential mixed method design is implied

because the first, purpose is to see if a critical

thinking skills intervention can facilitate increase in

students CT skills. The second purpose, based on

outcomes of the intervention effect, is a follow up

qualitative study to validate how the implied method

(i.e. intervention) have helped or failed to help in

improving students’ critical thinking skills.

Moreover, what other factors played a role in

affecting the CT intervention implementation. This

study uses a quan-qual mixed method research

design (Creswell, 2008; 2009).

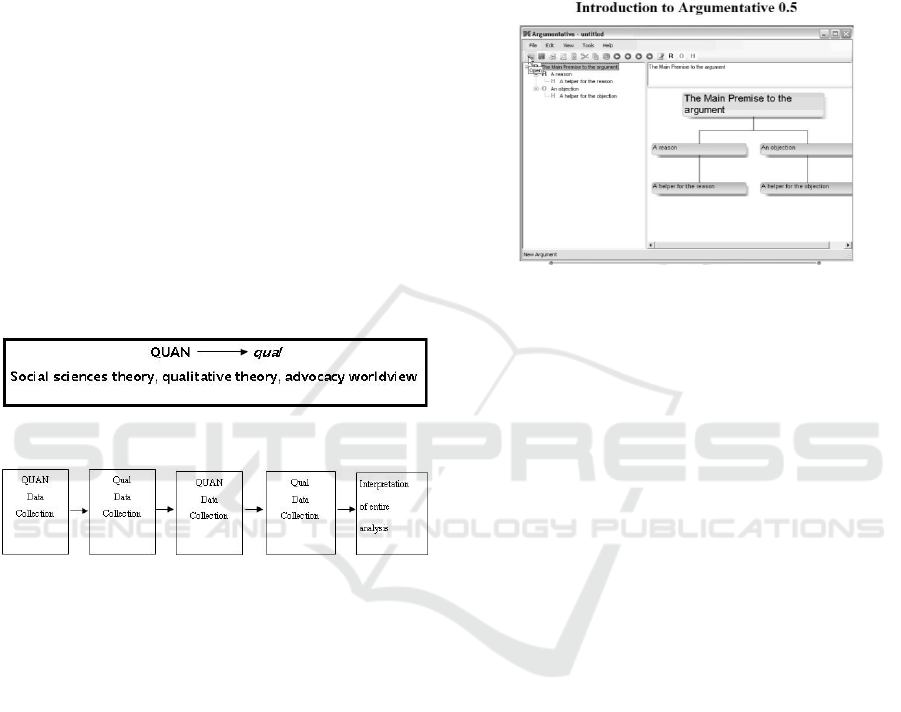

Figure 3.1a: Mixed method research design.

Figure 3.1b: Sequential explanatory design.

Figure 3.1a and 3.1b is the representation of the

methodology employed. The image is from Creswell

(2009) and explains the extent of using mixed

methods research design where main path of inquiry

remains quantitative therefore, bold and bigger,

followed by a qualitative methods approach.

Moreover, the data is collected in stages and

quantitative and qualitative data is collected in

sequence and exploratory manner, figure 3.1b shows

the sequential explanatory design

(Creswell, 2008).

The first QUAN (main quantitative) phase of the

research study follows a quasi-experimental two

group pre-test post-test design to look at the

effectiveness of an instructional intervention on

students of an initial teacher education program. The

second qualitative phase follows qualitative

classroom observations, journal notes and interviews

to explain the outcomes.

3.1.1 Argument Mapping Software

Freely available open source software

‘Argumentative’ is used for this study. The

researcher acknowledges sourceforge.net for

providing with free download. Figure 3.1.1 shows

screen view of the mapping software.

Figure 3.1.1: Argumentative software interface.

The figure 3.1.1 shows the interface that student

used to practice CT directed argument mapping.

3.2 Critical Thinking Skills

Interventions

A mixed approach (Ennis, 1998) is used to teach

critical thinking. The mixed approach CT “is taught

as an independent track within specific subject

matter” (Ennis, 1991; Abrami et al., 2008).

Independent track is ‘explicit’ where learners are

made aware that they are being taught CT elements

and how to think. Learning materials and teaching

strategies are used to categorically unravel elements

of CT. On the other hand, ‘embedded’ means when

it is engrained in existing curriculum and subject

specific topics are modified for deep learning while

applying the rules and elements of thought learned

via explicit approach. Together, these are known as

mixed approach to teach CT, for detail see Ennis

(1991) and Abrami et al. (2008). The first two weeks

comprises of explicit teaching of CT as an

independent thread and the last two weeks included

embedded teaching of CT within the Educational

Psychology subject matter. This was supported

practising the argumentation skills by argument

mapping software. As per mixed approach, the

second half of instructional intervention is related to

deep subject matter related practice into thinking

critically. This thread of the lesson plans is longer

than explicit CT teaching lesson (videos and

collaborative tasks of paper pencil concept mapping)

CSEDU 2016 - 8th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

332

and utilizes the visual representation tool (argument

mapping software) to help students’ lessen cognitive

load.

4 FINDINGS ABOUT THE

EFFECTIVNESS OF

VISUALIZATION TOOLS

The findings for effectiveness of visualization tools

(concept maps and argument maps) will be drawn on

standard classroom observations, research journal

notes (taken during the intervention implementation)

and seven semi-structured interviews of the

participants at the end of the intervention. During the

intervention it was observed that student worked

more attentively and with increased interest on class

tasks that’s involved preparing concept maps on

curriculum or general topics. They worked in small

groups (two to four) groups to brainstorm ideas on

topics and prepare simple concept maps.

For argument mapping we asked the participants

“What design features of instruction e.g. discussion

in community of inquiry, audio-video lectures on

critical thinking, learning with argument mapping

software, discussions in broader and deeper meaning

of curricular topics did you find most useful?”

following are the excerpts from qualitative data. The

data were analysed using critical analysis of the text

using thematic analysis approach.

Argument mapping plays a role in enhancing

students interest in learning and facilitating in

lessening the cognitive load those students felt while

learning CT. A student expressed learning with

[technology] argument mapping as an interesting

and different experience. To this student argument

mapping was helpful to structure the line of

argument, claims or evidence, how this can be

applied to other subjects as well [transferability of

CT skills]. Argument mapping also helped to

improve the writing of this student.

“Learning with argument mapping (Promptly), it

was different and interesting meaning we never

thought of information that it is relevant or

credible, no we don't. It improved my writing

and it motivated me for learning”.

Another student expressed that working with

argument mapping helped to develop a critical

aspect in thinking. The student felt motivated

through argument mapping [use of technology] even

when they were not interested in learning, computer

enhanced argument maps helped to see the structure

of thought and kept students interest. Learning in

technology enhanced environment was also liked

because teacher was there to guide, there was proper

planning and materials were readily available.

“I can criticize and handle a topic, situation.

Motivated through computer lab work, that

experience it was motivational as well because

we could see the structure of thought, and we

also saw teacher as a guide and instructor. There

was proper planning, software was available and

we were given all the materials, that phase was

motivating”.

Learning in groups was liked by this student as

this student thinks we learn socially with other

fellows. Learning argument mapping was easy due

to it being hands on and activity based. The reading

exercise was not liked by this student because she

does not like to read however discussion were of

interest and the student thinks we [she/he] learn a lot

from discussions.

“We learned to think critically in groups. With

my fellows, I could not make it with our friends

because it was tough. I found learning argument

mapping was easy because we did it practically,

by our hands in front of us and by our mind”.

The class teacher found the design of the

instruction very useful however there were some

problems. The students in teacher’s opinion are

unable to take the responsibility of learning for

themselves, they are not used to it although on the

contrary the teaching is going to change in Pakistan

but it will take time. These kinds of learning

experiences are not common yet students worked

eagerly. They will need more practice and drill on it,

with practice students will perform better on

argument mapping. The teacher stresses the

importance of methodology [instructional plan] and

design features especially communities of Inquiry,

collaboration and argumentative software and

expresses his interest in future use of this method

[CT embedded instruction].

“I found this design of instruction very useful

and very fine. This was totally new thing for

students, they worked on it eagerly but they

would need more practice and drills on this work.

So, I think with more practice they can perform

well on this argumentative software.

It’s really useful and workable strategy to enable

the students work in COI, collaboration, to work

on argumentative software”.

Effectiveness of an Instructional Intervention in Developing Critical Thinking Skills - Role of Argument Mapping in Facilitating Learning of

Critical Thinking Skills

333

5 DISCUSSION

The results and discussion of this paper is limited to

the qualitative data only. Argument mapping is a

part of teaching strategies of an instructional

intervention. The effectiveness of each teaching

strategy is not separately measured due to the design

limitation. The feedback on instructional design is

gathered at the end through interviews asking direct

question about design features of instruction. The

findings from participants’ accounts suggest that

argument mapping does facilitate in visualising

thinking, increasing interest, building opportunities

for collaboration and group work and learning to

build ‘valid, credible’ arguments. The students

found this approach useful because it help them to

think independently as well as thinking with their

fellows. This is in agreement with Brown and

Freeman (2000) and Kim and Reeves (2007) that

such teaching strategies can have direct or indirect

on development of CT skills.

One main expression that almost all participants

conveyed that it was hard to teach and be taught this

way and that learning critical thinking is tough

(Willingham, 2008, van Gelder et al., 2004). This is

not a surprise to us due the novelty of the structured

teaching programme in this context. Additionally,

research literature has many examples of evidence

that high order learning skills pose challenge to its

leaner and argument mapping helps avoiding

cognitive load (van Gelder, Bissett, and Cumming,

2004).

However, this study finds the usefulness of

argument mapping among participants to look at

information in a different way and learning with AM

easy due to its hands on practice feature and leaving

the learner do the thinking while only facilitating in

visualizing the structure of thought. This extends

Jonassen (1995) and Derry and Lajoi (1993) thesis

that the role of computer tools is that of a mind

extension and not that of teacher/expert.

It seems argument mapping work as a mind

extension tool for these students but needs more

practice. This is consistent with van Gelder, Bissett,

and Cumming, (2004) Davies (2011; 2012). The

students and class teacher also showed interest in

use of more such technologies in mainstream

teaching.

The learners may need to attend to each of the

elements and interactions between the elements

individually (e.g., audio-video lesson, class activities,

discussion on curriculum embedded topics and

preparing argument maps). Kalyuga et al., (2003)

and Sweller, Ayres, and Kalyuga, (2011a; 2011b)

have researched on reversal effects and the

interactions between levels of expertise and the

isolated or interaction elements effect in their work.

If implemented effectively, AM can be utilized

to gain increased effect sizes in critical thinking

skills interventions and improving the results of

instructional interventions. Interventions that have

complex materials and put high cognitive load on

learner’s minds may not bring significant results

over a short time as the learners will need to go

through exploratory phase, and then they will reach

understanding.

6 CONCLUSIONS/FUTURE

WORK

The following conclusions can be drawn from the

data in terms of role of argument mapping software

for facilitating learning of critical thinking.

a) Technology can be a positive adds on while

teaching complex constructs like CT however

the users’ familiarity, likeness and expertise

of handling technology may have a negative

effect rather than positive. One needs to be

careful or give training in advance before

introducing technology supported teaching –

learning techniques.

b) Argument mapping help in increasing

students’ interest and motivation. It facilitates

the cognitive processing of thinking among

students.

c) The quality of delivery of the intervention

components may be a major factor for the

failure of critical thinking skills interventions.

Interaction effect of complex elements can be

another reason for low effect sizes in critical

thinking research.

Argument maps are used as part of a multiple

components consisting teaching programme. The

study did not measure the effectiveness of AM and

cognitive load separately. The findings of this

research are based on qualitative data and a small

sample therefore, generalisations cannot be made.

However, one can conclude for this sample and

context on a n exploratory level argument maps

facilitate learning and construction of arguments by

providing the user the flexibility and structure to

thought that may lessen cognitive load. For teacher

educators, curriculum and courses should be

prepared with an explicit interest and emphasis on

critical thinking skills and argument mapping tools.

More practice and learning opportunities with

CSEDU 2016 - 8th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

334

computer supported argument mapping should be

part of critical thinking skills related instructional

interventions.

Future work may explore and measure the effect

of argument mapping in developing CT as part of

instructional intervention. Moreover, the relationship

between learning of critical thinking, cognitive load

the role of argument mapping in facilitating to lessen

the load and improving CT needs to be explored.

Overall the data from classroom observations,

research journal and participants’ interview

demonstrated the usefulness of argument mapping in

facilitating learning as instructional technology tools.

REFERENCES

Abrami, P.C., Bernard, R.M., Borokhovski, E., Wade, A.,

Surkes, M.A., Tamim, R. and Zhang, D., 2008.

Instructional interventions affecting critical thinking

skills and dispositions: A stage 1 meta-

analysis. Review of Educational Research, 78(4),

pp.1102-1134.

Adesope, O. O. and Nesbit, J. C., 2013. Animated and

static concept maps enhance learning from spoken

narration. Learning and Instruction, (27), pp. 1–10.

doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2013.02.002.

Browne, M. N. and Freeman, K., 2000. Distinguishing

features of critical thinking classrooms. Teaching in

Higher Education, 5(3), pp. 301–309. doi:

10.1080/713699143.

Buehl, M. M., & Fives, H., 2011. Best Practices in

Educational Psychology: Using Evolving Concept

Maps as Instructional and Assessment Tools. Teaching

Educational Psychology, 7(1), 62-87.

Cheema, A. B., & Mirza, M. S., 2013. Effect of concept

mapping on students’ academic achievement. Journal

of Research and Reflections in Education, 7(2), 125-

132.

Chiou, C., 2008. The effect of concept mapping on

students’ learning achievements and interests.

Innovations in Education and Teaching International,

45(4), pp. 375–387. doi: 10.1080/14703290802377240.

Creswell, J. W., 2008. Research design: Qualitative,

quantitative, and mixed methods approaches, Sage

Publications. Los Angeles, 3

rd

edition.

Creswell, J.W., 2009. Editorial: Mapping the field of

mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods

Research, 3(2), pp.95-108.S.

Davies, M., 2011. Concept mapping, mind mapping and

argument mapping: what are the differences and do

they matter?. Higher education, 62(3), pp.279-301.

Davies, M., 2012. Computer-Aided Mapping and the

Teaching of Critical Thinking. Inquiry: Critical

Thinking across the Disciplines, 27(2), pp.15-30.

De Jong, T., 2010. Cognitive load theory, educational

research, and instructional design: some food for

thought. Instructional Science, 38(2), pp.105-134.

Derry, S.J. and Lajoie, S.P. (eds.), 1993. Computers as

cognitive tools. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Pub.

Derry, S.J., 1996. Cognitive schema theory in the

constructivist debate. Educational Psychologist, 31(3-

4), pp.163-174.

Dewey, J., 1933. How We Think: A Restatement of the

Relation of Reflective Thinking to the Educative

Process. DC Heath and Company.

Dwyer, C.P., Hogan, M.J. and Stewart, I., 2012. An

evaluation of argument mapping as a method of

enhancing critical thinking performance in e-learning

environments. Metacognition and Learning, 7(3),

pp.219-244.

Dwyer, C.P., Hogan, M.J. and Stewart, I., 2013. An

examination of the effects of argument mapping on

students’ memory and comprehension

performance. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 8, pp.11-

24.

Ennis, R., 1991. ‘Critical thinking’, Teaching Philosophy.

14(1), pp. 5–24. doi: 10.5840/teachphil19911412.

Harrell, M., 2008. ‘No Computer Program

Required’. Teaching Philosophy,31(4), pp.351-374.

Harrell, M., 2011. ‘Understanding, evaluating, and

producing arguments: Training is necessary for

reasoning skills’. Behavioral and Brain Sciences,34(2),

p.80.

Horton, P. B., McConney, A. A., Gallo, M., Woods, A. L.,

Senn, G. J. and Hamelin, D., 1993. An investigation of

the effectiveness of concept mapping as an

instructional tool. Science Education, 77(1), pp. 95–

111. doi: 10.1002/sce.3730770107.

Jonassen, D.H., 1994. Technology as cognitive tools:

Learners as designers. IT Forum Paper, 1, pp.67-80.

Jonassen, D. H., 1995. Computers as cognitive tools:

Learning with technology, not from

technology. Journal of Computing in Higher

Education, 6(2), pp. 40–73. doi: 10.1007/BF02941038.

Jonassen, D.H., Reeves, T.C., Hong, N., Harvey, D. and

Peters, K., 1997. Concept mapping as cognitive

learning and assessment tools. Journal of interactive

learning research, 8(3), p.289.

Kalyuga, S., Ayres, P., Chandler, P. and Sweller, J., 2003.

The expertise reversal effect.

Educational

Psychologist, 38(1), pp. 23–31. doi:

10.1207/s15326985ep3801_4.

Kim, B. and Reeves, T.C., 2007. Reframing research on

learning with technology: In search of the meaning of

cognitive tools. Instructional Science, 35(3), pp.207-

256.

Kim, P. and Olaciregui, C., 2008. The effects of a concept

map-based information display in an electronic

portfolio system on information processing and

retention in a fifth-grade science class covering the

earth’s atmosphere. British Journal of Educational

Technology, 39(4), pp. 700–714. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-

8535.2007.00763.x.

Lajoie, S.P. and Derry, S.J. (eds.), 2013. Computers as

cognitive tools, Routledge.

Lim, K. Y., Lee, H. W. and Grabowski, B., 2009. Does

concept-mapping strategy work for everyone? The

Effectiveness of an Instructional Intervention in Developing Critical Thinking Skills - Role of Argument Mapping in Facilitating Learning of

Critical Thinking Skills

335

levels of generativity and learners’ self-regulated

learning skills. British Journal of Educational

Technology, 40(4), pp. 606–618. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-

8535.2008.00872.x.

Liu, P.L., Chen, C.J. and Chang, Y.J., 2010. Effects of a

computer-assisted concept mapping learning strategy

on EFL college students’ English reading

comprehension. Computers & Education, 54(2),

pp.436-445.

Moody, D.L., 2004. Cognitive load effects on end user

understanding of conceptual models: An experimental

analysis. Advances in Databases and Information

Systems (pp. 129-143). Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

Moreno, R., 2010. Cognitive load theory: More food for

thought. Instructional Science, 38(2), pp.135-141.

National Professional Standards for Teachers in Pakistan,

UNESCO,( 2009) www.unesco.org.pk.

Novak, J. D., 2004. Concept maps and how to use

them. INSIGHT, 6(2), pp. 15–16. doi:

10.1002/inst.20046215.

Novak, J. D. and Cañas, A. J., 2006. The origins of the

concept mapping tool and the continuing evolution of

the tool. Information Visualization, 5(3), pp. 175–184.

doi: 10.1057/palgrave.ivs.9500126.

Paas, F., Renkl, A. and Sweller, J., 2003. Cognitive load

theory and instructional design: Recent

developments. Educational psychologist, 38(1), pp.1-4.

Paas, F., Renkl, A. and Sweller, J., 2004. Cognitive load

theory: Instructional implications of the interaction

between information structures and cognitive

architecture. Instructional science, 32(1), pp.1-8.

Paas, F. and Ayres, P., 2014. Cognitive load theory: A

broader view on the role of memory in learning and

education. Educational Psychology Review,26(2),

pp.191-195.

Pea, R. D., 1985. Beyond amplification: Using the

computer to reorganize mental functioning.

Educational Psychologist, 20(4), pp. 167–182. doi:

10.1207/s15326985ep2004_2.

Salomon, G., Perkins, D. N. and Globerson, T., 1991.

Partners in Cognition: Extending human intelligence

with intelligent technologies. Educational Researcher,

20(3), pp. 2–9. doi: 10.3102/0013189x020003002.

Sweller, J., 1988. Cognitive load during problem solving:

Effects on learning. Cognitive science, 12(2), pp.257-

285.

Sweller, J., 1994. Cognitive load theory, learning

difficulty, and instructional design. Learning and

instruction, 4(4), pp.295-312.

Sweller, J.,1999. Instructional design. Australian

Educational Review.

Sweller, J., Ayres, P. and Kalyuga, S., 2011a. Interacting

with the External Environment: The Narrow Limits of

Change Principle and the Environmental Organising

and Linking Principle. Cognitive Load Theory (pp. 39-

53). Springer New York.

Sweller, J., Ayres, P. and Kalyuga, S., 2011b. The

modality effect. Cognitive load theory , pp. 129-140.

Springer New York.

Tan, S. Y., 2012. Enhancing Critical Thinking Skills

Through Online Tools: A Case of Teacher

Trainees. OIDA

International Journal of Sustainable

Development, 3(7), 87-98.

van Gelder, T., 2013. ‘Argument mapping’. Encyclopedia

of the Mind . doi: 10.4135/9781452257044.n19.

van Gelder, T., Bissett, M. and Cumming, G., 2004.

Cultivating expertise in informal reasoning. Canadian

Journal of Experimental Psychology/Revue

canadienne de psychologie expérimentale, 58(2),

p.142.

Willingham, D.T., 2008. Critical thinking: Why is it so

hard to teach?. Arts Education Policy Review, 109(4),

pp.21-32.

CSEDU 2016 - 8th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

336