Advancing Research in Enterprise Architecture

An Information Systems Paradigms Approach

Ovidiu Noran

School of Information and Communication Technology, Griffith University, Nathan QLD, Australia

Keywords: Enterprise Architecture, Information Systems, Research Paradigms, Action Research.

Abstract: Enterprise Architecture (EA) is an Information Systems (IS)-related domain aspiring to become a mature

discipline underpinned by its own schools of thought. As with other emerging research areas, currently there

is no widespread consensus on EA formal theoretical foundations and associated paradigms; thus, the EA

researcher needs to find and tailor paradigms and research methods from related disciplines. As a possible

solution contributing towards the maturing of the EA field, this paper advocates the application of social

science-inspired qualitative research methods and paradigms typically engaged in the IS area to EA research.

The paper starts by performing a critical review of the mainstream IS research assumptions, methods and

paradigms in view of their suitability and expressiveness for the EA research endeavour according to

ontological and epistemological assumptions specific to EA. Subsequently, the paper demonstrates the

application of the reviewed IS research artefacts through a sample EA research strategy framework based on

an IS-inspired reflective and iterative action research paradigm.

1 INTRODUCTION

Enterprise Architecture (EA) is a domain related to

Information Systems (IS) that attempts to bridge the

management, IS, Information Technology (IT) and

engineering in order to guide organisations through

the change processes involved in fulfilling their

strategies. In effect, EA translates business vision and

strategy into change by creating, communicating and

improving the key principles and models that describe

the enterprise’s future state and enable its evolution

(Gartner Group, 2008). Several EA research

directions currently exist; however, the ontology of

EA is not yet widely agreed upon. As the EA schools

of thought (Lapalme, 2012) are presently not mature

enough to agree on formal theoretical foundations and

associated paradigms, the EA researcher needs to find

'best matches' in paradigms and research methods

from related disciplines, notably IS. Finding and

customising relevant research artefacts is in fact

beneficial towards promoting creativity in the

discovery of innovative approaches to answer

research problems in the EA domain.

This paper aims to support the search for suitable

artefacts by initially performing a critical review of

the mainstream IS research assumptions, methods and

paradigms in view of their suitability and

expressiveness for the EA research endeavour. This

is followed by an attempt to demonstrate the use of

the IS research artefacts reviewed to EA, in the form

of an example EA research strategy framework

featuring a reflective and iterative action research

paradigm background.

2 RESEARCH ASSUMPTIONS

The research work described in this paper has

examined the paradigms used in classifying the IS

schools of thought described by Iivari (1991) in order

to select appropriate EA research assumptions and

methodologies. From the start, it must be noted that

there is a partially acknowledged connection between

research methods and epistemological assumptions

(Burrell and Morgan, 1979; Iivari, 1991); that is,

adopting a particular epistemological stance may bias

the researcher towards particular research methods.

The view taken in this study is that such dependence

and biases are acceptable, provided they are

acknowledged by the researcher and taken into

account when evaluating the research results.

Noran, O.

Advancing Research in Enterprise Architecture - An Information Systems Paradigms Approach.

In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS 2016) - Volume 2, pages 539-548

ISBN: 978-989-758-187-8

Copyright

c

2016 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

539

2.1 Ontological Assumptions

2.1.1 The EA View of IS: Technical System

and Social System

The EA view of IS is important in order to underpin

the stance towards using research artefacts

originating in the IS body of knowledge. Thus, EA

typically considers IS to be a subsystem of an

enterprise used to collect, process, store, retrieve and

distribute information within the enterprise and

between the enterprise and its environment (Bernus

and Schmidt, 1998), comprising “not only

technologies but people, processes and organisational

mechanisms” (Stohr and Konsynsky, 1992) “aimed at

maintaining an integrated information flow

throughout the enterprise” (Bernus and Schmidt,

1998) and providing the quality and quantity of

information “whenever and wherever needed” (ibid.).

For EA, the business change processes are the

main driver of IS development and the object of IT

requirements (Earl, 1990). The above-mentioned IS

definition implies a dualistic EA view of IS, where

mechanistic (technical), but also utilitarian (users)

and reflective (designers) aspects (Swanson, 1988)

must be considered. Thus, in an EA perspective the

IS as a fundamental component of the enterprise

exists within a complex organisational, political and

behavioural context (view shared by the Decision

Support System IS school of thought (Keen and Scott

Morton, 1978)). EA acknowledges that the IS plays

an essential role in the design and operation of the

organisation/s, both as a technical system and as an

organisational and social one (Pava, 1983),

depending on the view taken: ‘tool’ or ‘institutional’

(Iacono and Kling, 1988).

Vice versa, from an IS viewpoint, EA is a holistic

change management paradigm that bridges

management and engineering best-practice,

providing the “[…] key requirements, principles and

models that describe the enterprise's future state. […].

Thus, EA comprises people, processes, information

and technology of the enterprise, and their

relationships to one another and to the external

environment” (Gartner Research, 2012). This EA

definition reinforces the view of enterprises as

collaborative social systems composed of

commitments (Neumann et al., 2011) and socio-

technical systems (Pava, 1983) with voluntaristic

people (McGregor, 1960) in a complex

organisational, political and behavioural context

(Iivari, 1991; Markus, 1983).

2.1.2 EA View of Data: Constitutive

Meanings, Partially Descriptive Facts

Similar to the Software Engineering school approach

(Fairley, 1985; Sommerville, 1989), the modelling

involved in EA sees information as an interpretation

of reality, a way to communicate and to achieve a

common understanding. However, as Lehtinen and

Lyytinen (1986) assert, a performative function of

data also exists, enabling users to do things; in EA,

this function translates into simulations, forecasts and

operation (e.g. using executable enterprise models).

Adopting a dual view of the data allows creating

models that promote common understanding

(descriptive facts) while at the same time allowing for

subjective meanings that construct possible realities

(e.g. forecasts and designs). In addition, the

interpretive view of data allows constructing

customised models targeted to audiences having

various competencies; notably however, these models

must be views of a unique agreed-upon perception of

‘reality’, typically enabled by a consistent set of

underlying meta-models and ontologies.

2.1.3 EA View of Human Beings:

Voluntaristic with Deterministic

Elements

A deterministic view of humans as adopted by the SE

and Implementation schools of thought appears to be

generally inappropriate to the EA research stream. In

contrast, the voluntaristic position advocates user

participation (Lundeberg et al., 1981) since end-user

rejection of a technically successful project will

ultimately render it useless (Swanson, 1988);

motivational (encouraging / inhibiting) factors

inherently present in organisations also promote a

voluntaristic view of human beings. Therefore, a

human view relevant to EA has to reflect aspects of

Theory Y (McGregor, 1960) where people are

voluntaristic in nature but display deterministic

elements. This is because stakeholders are typically

influenced by personal context, previous experiences

(e.g. unpopular systems forced on the organisation)

and organisational culture (e.g. clan, adhocracy,

hierarchy, market (Cameron and Quinn, 2006)).

2.1.4 EA View of Technology: Human

Choice with Deterministic Elements

EA studies typically produce a variety of technically

acceptable solutions. Therefore, human choice is

essential in the adoption of a particular (type of)

solution to a given EA problem. The adoption of a

specific solution by a group of people is a result of the

ICEIS 2016 - 18th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

540

complex interaction of several factors such as

technical needs and individual and group ambitions,

agendas and beliefs. Thus, the acceptance and

adoption of a proposed 'umbrella' solution by

(potentially competing) human groups is very much a

political process that involves taking ownership by

identifying and confirming contributions to a

common overarching framework. By taking into

account the non-deterministic nature of humans it is

possible to achieve a synergy towards an inherently

common, although differently perceived final

purpose. In EA, achieving unanimously agreed-upon

meaningful enterprise models and modelling

methodologies for the present (AS-IS) and chosen

future (TO-BE) states is a core enabler of any

successful change effort.

The deterministic elements of technology must

also be considered, e.g. in order to model the effects

of externally managed or imposed technological

infrastructure (typically caused by outsourcing or by

misalignment of IS vs. enterprise goals). Therefore, a

deterministic view may suitable to some extent to

model an existing AS-IS situation, while a human

choice view is perhaps best adopted in designing

possible desired TO-BE states.

2.1.5 EA View of Organisations:

Interactionism, Structuralism to Some

Extent

A static, structuralist view of the organisation allows

constructing models that are relatively stable.

However, the interactionist view of an organisation

has a logical connection to the voluntaristic view of

people and the human choice view of technology

previously reviewed. Thus, the existence of

organisational culture, power, politics and

‘discretionary coalitions’ (Pava, 1983) is undeniable;

any undertaking towards integration and

reconciliation of the existing and emergent EA

framework and methodologies of the various schools

of thought must take this fact into consideration.

In the global market conditions, successful

organisations are typically agile - continuously

evolving in response to, or even to pre-empt changes

in the environment. As a result, enterprise models

must be either promptly constructed as a 'snapshot' of

the current state and regularly updated, or constructed

in a way that reflects the modelled target over its

entire life cycle. In the current research, the

'structuralism to some extent' approach adopted

allows modelling the inherent degree of inertia

present in organisations and the user resistance to

change; these issues need to be properly addressed so

as to obtain user satisfaction and cooperation and thus

make organisational changes 'stick'.

2.2 Epistemological Assumptions

Enterprise models as a core component of the EA

effort are being constructed for various reasons - such

as enhancing the understanding of the enterprise

structure, operation and lifecycle, enabling enterprise

operation via executable models, or allowing to test

various future state scenarios. Invariably though, the

declared, tacit or emerging ultimate purpose of

enterprise modelling within EA is change.

Consistent with the ontological assumptions

previously adopted (e.g. voluntaristic human beings

and technology as a human choice), perception,

interpretation and understanding are crucial to the

development of consistent enterprise models and

agreed-upon EA methodologies. For example,

technical-wise 'perfect’ methods to construct specific

models are pointless if the intended audience does not

possess the required competencies to understand

them and therefore will seldom or never put them to

use. Thus, in the author’s opinion, EA research must

adopt an anti-positivistic epistemological stance

focused on the interpretations of the stakeholders.

This will allow to decide the required formalisation

extent of the enterprise architecture framework (EAF)

artefacts (e.g. modelling frameworks, methodologies,

etc.) in order to match the intended audience

competencies; this will promote shared user

understanding leading to commitment to (and thus

actual use of) the resulting EA endeavour

deliverables.

Although implicit associations of the

epistemology with the research methods exist (see

Burrell and Morgan (1979), the author supports the

view of relative independence of the two as advocated

by Iivari (1991). This stance allows some flexibility

in choosing the research methods that best suit the

research, while keeping within the chosen

epistemological stance.

2.3 Ethics of Research

The majority of IS schools of thought adhere to

Iivari’s (ibid.) view that practical relevance

unavoidably implies a means-end approach. This is

reflected in the EA perspective: research has to serve

the interests of the host organisation (ibid.), while

considering stakeholders’ satisfaction; practical

research outcomes would be useless if not fully

understood and accepted by the intended users and

decision makers. Thus, according to Lucas (1981) the

Advancing Research in Enterprise Architecture - An Information Systems Paradigms Approach

541

users must firstly be satisfied with and have

favourable attitudes towards the EA artefacts

produced; as a result, they will actually use them and

by doing so, achieve payoffs for the organisation.

Hence, an interpretivist approach appears to be

appropriate in EA research so as to investigate the

motivation, purpose and effects of the EA efforts,

culminating in the previously stated view that the

fundamental aims of the EA endeavour are

understanding and change.

2.4 Other Research Assumptions

2.4.1 Research Paradigm

In view of the previous assumptions, an 'umbrella'

research paradigm for this study is close to the social-

relativist area according to Hirschheim and Klein

(1989), or the interpretivist domain as defined by

Burrell and Morgan (1979) (see

Figure 1).

Functionalist tendencies may be present, without

necessarily denying the existence of conflict, or

adopting a positivist approach (as argued by this

framework’s critics, e.g. Chua (1986) and Nurminen

(1997)).

Figure 1: Proposed EA position within mainstream IS

research paradigms.

2.4.2 Role of the EA Researcher

Within the framework defined by Hirschheim and

Klein (1989), the EA researcher appears to be a

facilitator in an anti-positivistic stance, believing that

data can be interpreted in different ways by various

stakeholders and taking a social-relativist approach

when tackling the acceptance and effects of the EA

artefacts on the organisation. However, due to the

intrinsic mission of EA (change), the researcher must

reconcile the facilitating role with that of a systems

expert, acknowledging that data describes a unique

reality (vs. information which is the interpretation of

data by the stakeholders) and that research must have

practical outcomes. Thus, the EA researcher acts to

facilitate the audience's understanding of the present

and possible future states of their organisations, but at

the same time plays an expert role in producing a

commonly agreed-upon EA methodology model and

associated deliverables. These artefacts are essential

in guiding the selection of suitable steps in the EA

process and enable additional modelling aspects and

formalisms as necessary for the target audiences.

3 RESEARCH METHODS

This study has used the IS research taxonomy

presented by Galliers (1992) as the main repository of

potential research methods suitable for EA.

Generally, humanities-inspired idiographic research

methods which consider each subject as an ‘agent’

with a unique life history appear to better satisfy the

particular needs of EA research: each enterprise

presents unique features which are best investigated

by getting close to it and exploring its background and

life history. Therefore, anti-positivist-specific

methods such as action research (AR) and case study

feature prominently among the chosen methods. The

researcher has adopted Jick ‘s (1979) view in respect

to the importance of triangulation and of the

'triangulating investigator' (establishing convergence

of results) in research.

3.1 Action Research (AR)

AR is suitable for EA because often the researcher

directly participates in the Universe of Discourse

being researched and because typically, the problems

in this area contain both theoretical (research) and

practical (real-world) aspects that need to be

addressed; this method is also be consistent with the

interpretivist (Burrell and Morgan, 1979) and social

relativist (Hirschheim and Klein, 1989) stances

(Jönsson, 1991). In addition, Davison (2001) argues

that problems for which previous research has yielded

a validated theory are well suited for AR: the action

researcher intervenes in the problem situation,

applying the theory provided, evaluating its

usefulness and potentially enriching it as a result of

the evaluation. This matches the EA situation where

often usable and proven, albeit not always complete

or fully established theoretical artefacts (e.g. EAF

elements) are provided. Notably, AR is perceived by

Subjective

Objective

Conflict

Order

Functionalist

Social Relativist

(Interpretivist)

Radical

Structuralist

Neo-Humanist

Subjective

Objective

Conflict

Order

Functionalist

Social Relativist

(Interpretivist)

Radical

Structuralist

Neo-Humanist

ICEIS 2016 - 18th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

542

some IS schools of thought as an iterative process in

which reflection is the crucial phase (Davison, 2001).

There is an on-going debate about rigor vs.

relevance in the IS field. These two apparently

opposing aspects can be reconciled in the author’s

opinion: AR can produce results usable in practice

(relevance) (Benbasat and Zmud, 1999), while a

cyclic type of AR may be used to build the necessary

scientific rigor (Davidson et al., 2004; Davison,

2001). This resolution is also applicable to EA: AR

can produce an applicable repository of EA artefacts

(relevant to practice) and at the same time build the

necessary theoretical rigor and refine these

deliverables with each research iteration. Thus, the

author considers reflection and iteration applied to

AR as essential and equally important aspects when

applied to the EA domain.

3.1.1 EA-specific AR Features and Issues

AR as a qualitative method usable in IS (Baskerville

and Wood-Harper, 1996) displays a great diversity of

methods (Chandler and Tvorbert, 2003; Lau, 1997);

thus, it needs to be further scoped for the EA domain,

using frameworks such as described by Chiasson and

Dexter (2001). This framework contains four AR

characteristics that may be used to distinguish

between various AR approaches: the AR process

model (iterative, reflective, or linear), the structure of

each AR step (rigorous or fluid), the researcher

involvement (collaborative, facilitative, or expert)

and the AR primary goals (organisational

development, system design, scientific knowledge or

training). In terms of the viewpoints of this

framework, the most beneficial AR process model for

EA would include the repetitive use of a sequence of

activities (iterative AR) and reflection upon the

results obtained (reflective AR), leading to

uncovering and resolving potential differences

between the theory in use and the espoused theory

(Avison et al., 2001). Furthermore, as the typical turn-

around period for an EA field test / case study is often

measured in years, it can be argued that the AR steps

should be rigorous, since appropriate succession and

timing of the AR phases are essential to a meaningful

research outcome. In regards to involvement, the EA

researcher is typically both a facilitator and an expert.

As for the last framework viewpoint, the primary

goals of AR in EA are typically system design (since

EA perceives enterprises as systems of systems

(Carlock and Fenton, 2001)), scientific knowledge

(advancement of EA as a discipline) and

organisational development (as organisational change

processes are typically a major aspect in EA).

Avison et al. (2001) state several essential issues

that need to be addressed for a successful AR

approach - namely initiation, determination of

authority and degree of formalism. In respect to EA,

initiation appears to be typically both research and

practice-driven. For example, in the process of the

development of the sample research strategy

framework presented in Section 5, a brief analysis of

the current EA environment has revealed research

fragmentation and incompatibility of the enterprise

modelling methods available, leading to the practical

problem of what and how to use, for which problem

(problem-driven). Authority determination in EA-

specific AR for the enterprise architect and EA team

is typically decided according to the policies of the

hosting organisation and the standing of the project

champion (e.g. CEO vs. office manager). Finally, the

degree of AR formalism in EA will have to be high,

so as to enforce rigorousness and ensure the

stakeholders’ trust and support of the architecting

effort.

From the above it can be concluded that EA

research should consider an iterative and reflective

AR type, with iterations occurring in a dual cycle

representing the theoretical and practical significance

of the research undertaken (Checkland, 1991; McKay

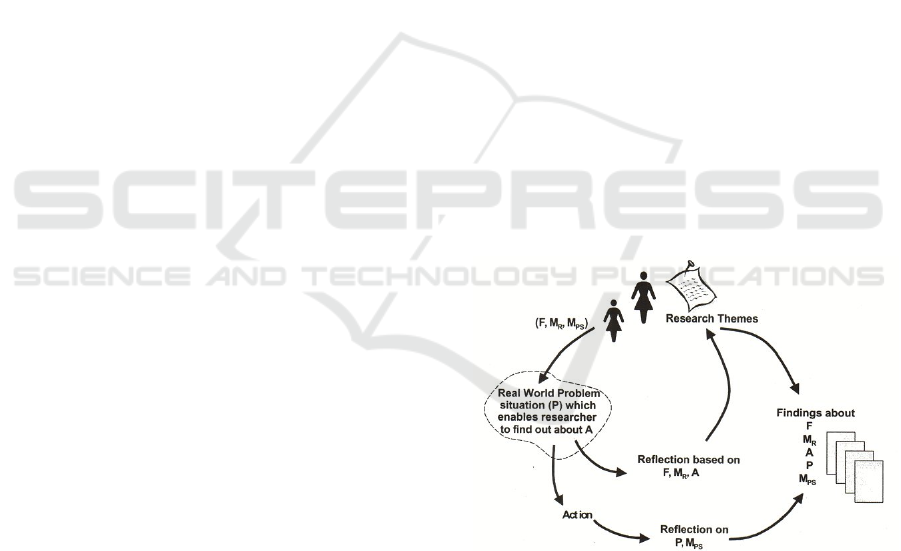

and Marshall, 2001). This is represented in Figure 2,

where the meaning of the symbols can be interpreted

from an EA viewpoint as follows:

Figure 2: The dual cycle of Action Research (Checkland,

1991; McKay and Marshall, 2001).

• F: the theoretical EA framework adopted (e.g.

an EAF or combination thereof);

• M

R

: the EA research method (or a combination

thereof);

• M

PS

: the EA problem solving methodology (or

meta-methodology (Noran, 2008));

• A: the theoretical EA problem to be solved;

Advancing Research in Enterprise Architecture - An Information Systems Paradigms Approach

543

• P: the real world EA problem; e.g. how to

combine and apply existing EAF elements and

domain knowledge for a given EA task.

3.2 Conceptual Development

This constructive type of research method (Iivari et

al., 1998) allows for the necessary creation of EA

artefacts. Therefore, in an iterative AR approach each

research cycle should include a conceptual

development phase to build or refine the EA research

deliverables.

3.3 Descriptive / Interpretive Research

This method can be involved for example in a critical

literature review phase. It allows the researcher to

develop a cumulative knowledge of the EA domain

issues and thus ensure that the current research is

relevant and builds on previous achievements

(Galliers, 1992). For example, in the research

approach framework proposed further on in Section

5, the critical review prepares the researcher for the

entry in the iterative AR cycles by contributing to the

creation of a structured repository of EAF elements.

3.4 Simulation

Galliers (1992) and Eden and Chisholm (1993) argue

that simulation is well-suited to methodology and

theory development, testing and extension. The large

turn-around time involved in EA field tests makes

simulation an effective choice for artefact

development and testing, bearing in mind that the

results obtained can only be checked for internal

validity (Trochim, 2000). In the proposed research

approach framework, simulation is used for prototype

testing and development in the early stages of the

research so as to achieve the quality and detail

necessary for the typically time-consuming EA field

testing.

3.5 Field Experiment and Case Study

This method can be used in EA to externally validate

(i.e. in a real-world situation) the artefact under

development. Thus, in an iterative AR approach, field

experiments would represent the 'action' part of AR

(see e.g. Figure 3) employed in each cycle.

Describing the present states and relevant past

events of the organisations involved in the simulation

and field experiments is essential to the development,

refinement and validation of the artefacts being

developed in an EA research endeavour. In addition,

the potential effects of the research product(s) on the

target organisations should also be investigated. For

these reasons, case study (in conjunction with field

experimentation) also constitutes a useful method for

EA research.

An interesting proposition is the dual use of case

studies (see (Lin, 1998)) in EA: in an interpretive

fashion so as to explore / generate theory and to ask

questions, but also in a positivistic way, to find

predictable aspects (infer EA theory) and test the

effects of proposed artefacts (e.g. EAF elements,

associated methodologies and so on).

3.6 Ethnography

This anthropology-based interpretive research

method aims to explore ‘contextual webs of meaning’

(Myers, 1997), i.e. examine human actions in a

socially constructed context. In particular, post-

modernist (Harvey, 1997) and critical (Myers, 1997)

ethnographies appear to be well-suited for the

exploration of the complex and changing social

context of EA. Ethnography is recommended as a

suitable method for EA research since it may be

effectively used to study the organisational effects of

implementing the change processes driven by

enterprise models created during EA projects.

3.7 Survey

Surveys are a possible alternative to the critical EA

literature review. However, employing surveys of the

major EA schools of thought may prove less useful

due to typical problems such as sensitivity to data

gathering methods (typically questionnaire and

structured interviews), self-selection and interviewee

observation and counteraction of the interviewer

strategy, which are likely to be magnified in the

context of the currently pronounced fragmentation of

current EA research and polarisation of the EA

schools of thought.

3.8 Longitudinal Research

This approach typically allows for the measurement

of behaviour (involving several other research

methods) at a number of points in time during a finite

time span (Galliers, 1992). Longitudinal research

applied in EA could be useful in the same manner as

ethnography; however, due to the extensive period of

time involved (compounded by the typically long

turn-around of EA field tests), it may involve high

cost, obsolesce, bias and could require significant

resources.

ICEIS 2016 - 18th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

544

4 DATA GATHERING METHODS

The use of primary data in EA is subject to typical

collection method pitfalls. For example,

questionnaires are subject to bias and self-selection

on the respondents' part (Galliers, 1992), delays and

low rate of response, while interviews can be affected

by hidden agendas and by the interviewee lack of self-

disclosure. A better alternative is participant

observation, which can be employed in the field

testing phase to gather primary data, subject to the

research team being representative of the project

environment viewpoints (Trauth, 1997). For example,

participant observation and semi-structured

interviews have been used in the field experiments

employed to test and validate the proposed research

approach framework in Section 5, with the researcher

participating in working groups in charge of EA

artefacts’ life cycle management. The collected data

has been used in the reflection and triangulation

phases of the research framework testing and

validation.

The use of secondary data for research purposes

has critics (Bowering, 1984; Kiecolt and Nathan,

1985) and defenders that argue for its value in

complementing or even replacing primary data

(Jarvenpaa, 1991). Similar to the case of IS, one may

conclude that secondary data may be used in EA if the

purpose and the methods used in the original data

collection can be rigorously ascertained.

Note that in EA, data reflecting business

processes, strategies, networks etc. may provide a

decisive edge to a business in a competitive situation.

Hence, in the EA domain most such data is

confidential thus requiring trust building between the

researcher and the practitioners within the

organisation; this can be achieved e.g. by the adoption

of an ethnographical approach, whereby the

researcher is immersed in the participant

organisation(s) for a significant period of time.

5 CASE STUDY: AN AR-BASED

EA RESEARCH STRATEGY

FRAMEWORK

5.1 Overview

This section presents a sample application of some of

the research methods previously reviewed within a

proposed EA research strategy framework. Note that

in this context, AR is perceived as an overarching

research approach (Galliers, 1992) providing a

context for other research methods – here, conceptual

development, simulation, field testing and case study.

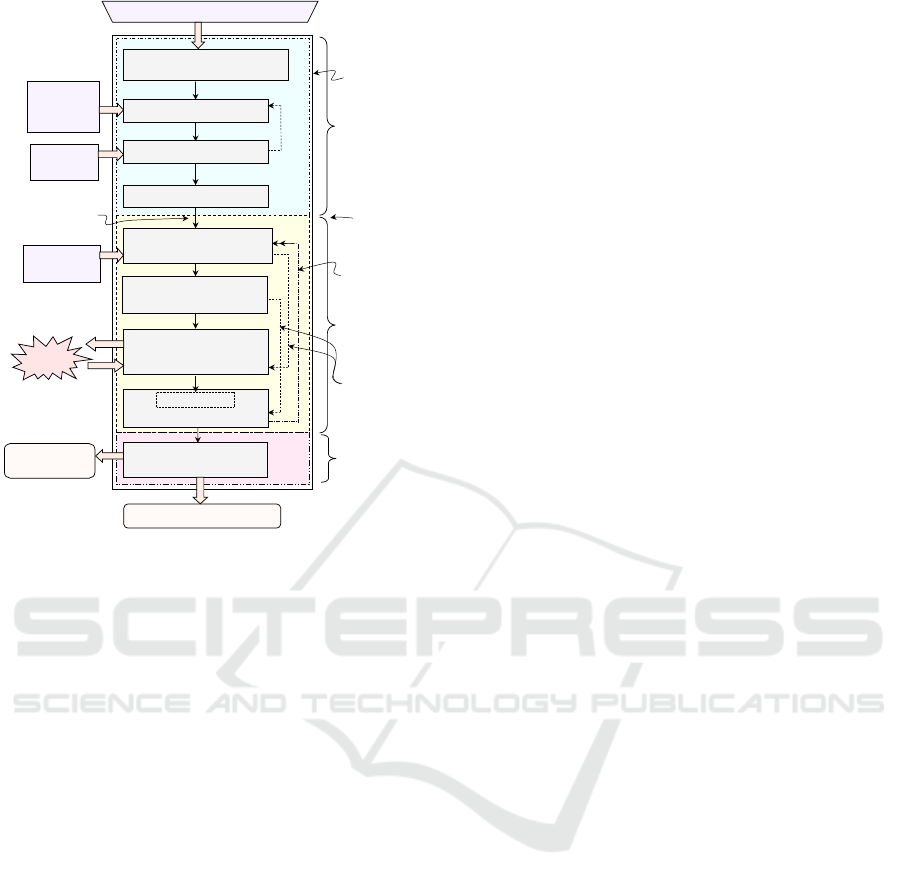

Figure 3 shows the customised dual cycle of the

research strategy employed, based on the work of

McKay and Marshall (2001) and Checkland (1991)

previously explained in Section 3.1.1 and illustrated

in Figure 2.

The inner cycle comprises conceptual

development and simulation followed by reflection.

Besides checking internal validity, this cycle aims to

promptly refine and bring the research deliverables to

a level suitable for field testing (which in EA may

span over significant periods of time, thus requiring a

mature prototype for a meaningful result). The outer

cycle performs a field experiment combined with case

study; the results are reflected upon and then

triangulated with the simulation result.

Several iterations may occur within the inner and

outer cycles; the exit from these cycles is triggered by

mitigation between the required level of artefact

maturity and quality and available research resources.

The results are then refined one last time and critically

assessed in regards to their contribution towards

theory (EA body of knowledge) and practice (e.g. EA

design and operation artefacts).

5.2 Brief Explanation of the Most

Relevant Framework Components

5.2.1 Critical Literature Review

Typically, EA problems require the use of

components belonging to more than one EAF. The

effective application of such EA components requires

their review and categorisation in respect to their life

cycle and universe of discourse coverage, using a

common reference that has to be expressive and

generic enough to accommodate the scope of all

assessed frameworks. Typically this requirement is

fulfilled by a suitable theoretical model; in several of

the case studies used to develop, test and validate the

sample research strategy framework presented here

(e.g. (Noran, 2009, 2012, 2014; Noran and Panetto,

2013)) this generic, albeit expressive reference has

been provided by ISO15704 Annex A (ISO/IEC,

2005), a document outlining requirements for EAFs.

From the aforementioned case studies it has also

emerged that a mixed descriptive / interpretive

research approach (Galliers, 1992) would be

beneficial for the EA literature review - i.e., rather

than merely appraising the state-of-the-art, also

attempt to assess and interpret the reviewed

knowledge using a consistent EA terminology

(provided by the adopted theoretical model).

Advancing Research in Enterprise Architecture - An Information Systems Paradigms Approach

545

Figure 3: A sample IS AR-based EA research strategy

framework using Galliers (1992) and Wood-Harper (1985).

5.2.2 Theory Testing (Field

Experimentation/ Case Study)

The field experimentation method is associated here

with case study in order to record the effects of EA

artefacts’ application on the target enterprise. As can

be observed from Figure 3, field testing is a two-way

process: external validation is achieved (input from

the environment) while at the same time practical

outcomes are created (output to the environment).

Member checking (Trauth, 1997) should be regularly

involved by validating the models produced with the

stakeholders of the involved organisations. The

feedback thus gathered can be used to reflect on the

research and suitably adjust the artefacts in

subsequent conceptual development phases within

the AR research cycle iterations.

5.2.3 Reflection / Theory Extension

Reflection is necessary after each iteration in order to

elaborate on the field experiment / case study

conclusions and to assert possible causal relationships

(Trochim, 2000). Reflection results in theory

extension and refinement proposals, which are fed

into the conceptual development phase of the next

research iteration. In testing the framework, the AR

iterations have deliberately involved largely diverse

environments, so as to enable an effective

triangulation (Jick, 1979) ascertaining the

convergence of the results obtained in the simulation

and field experiments.

5.2.4 Final Refinement / Critical Assessment

The final refinement phase aims to address

concluding change requests from the reflection

contained in the last AR iteration and to provide an

overarching critical assessment in order to test the

thoroughness of the research in adhering to the stated

AR strategy and researcher's stance, biases and

assumptions. The final results (theoretical and

practical EA research deliverables) are then

disseminated.

5.3 Testing and Application in Practice

The above-described research strategy framework

has been tested during its development in several

practical EA research projects spanning collaborative

networks, disaster management, standards

management, healthcare and environmental

management domains. The lessons learned from each

application (not described here due to space

limitations, however published separately) have

contributed to the development and progressive

refinement of the framework.

6 CONCLUSIONS

AND FURTHER WORK

EA as a maturing IS-related field of research is in

need of suitable and proven research patterns. This

paper has performed an EA-focused critical review of

the main IS ontological and epistemological

assumptions, research paradigms and methods in

view of their suitability given the specific context and

requirements presented by EA. As a general

conclusion, IS provides a rich and useful repository

of research artefacts which, suitably customised, can

significantly assist the EA research endeavour.

The IS research artefacts appraisal was followed

by putting together an illustrative research strategy

framework for EA using a selection of research

methods from the reviewed set, on the background of

an iterative and reflective AR approach.

The sustained quest to find, combine and adapt

suitable research paradigms to tackle various EA

research questions and practical tasks is expected to

continue to contribute towards the advancement of

Preliminary Research Question

R

esearch Design

Critical Literature Review

Adopt / Confirm Theory

Restate Research Question

Theory testing

(simulation )

Theory testing

(field experiment /

case study)

(Triangulation)

Reflection / Theory extension

Conceptual development

AR:

cycle

Previous

Research

Final Refinement

Critical Assessment

Action

Research (AR):

prepare

AR:

exit cycle

AR:

enter cycle

Action

Reflect, decide &

acknowledge AR

Enterprise

Architecture

Frameworks

Best Practice,

Case Studies

Research /

environment

boundary

Contributions

towards Practice

Contributions towards Theory

Alternative

paths

Cycle

(within limits)

Previous Research (Case study & AR)

ICEIS 2016 - 18th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

546

EA research by making valuable contributions to the

EA body of knowledge.

REFERENCES

Avison, D., Baskerville, R., & Myers, M. 2001. Controlling

action research projects. Information Technology &

People, 14(1), 28-45.

Baskerville, R., & Wood-Harper, A. T. 1996. A critical

perspective on action research as a method for

information systems research. Journal of Information

Technology, 11(3), 235-246.

Benbasat, I., & Zmud, R. 1999. Empirical research in

information systems: The practice of relevance.

Management Information Systems Quarterly, 23(1), 3-

16.

Bernus, P., & Schmidt, G. 1998. Architectures of

information systems. In P. Bernus, K. Mertins & G.

Schmidt (Eds.), Handbook on architectures of

information systems (pp. 1-9). Heidelberg: Springer

Verlag Berlin.

Bowering, D. J. 1984. Secondary analysis of available data

bases. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Inc.

Burrell, G., & Morgan, G. 1979. Sociological paradigms

and organisational analysis. London: Heineman.

Cameron, K., & Quinn, R. E. 2006. Diagnosing and

changing organizational culture: Based on the

competing values framework (Vol. 4). Beijing, CHina:

Renmin University Press.

Carlock, P. G., & Fenton, R. E. 2001. System-of-systems

(sos) enterprise systems for information-intensive

organizations. Systems Engineering, 4(4), 242-261.

Chandler, D., & Tvorbert, B. 2003. Transforming inquiry

and action: Interweaving 27 flavors of action research.

Action Research, 1(2), 133-152.

Checkland, P. 1991. From framework through experience

to learning: The essential nature of action research. In

H.-E. Nissen, H. K. Klein & R. Hirschheim (Eds.),

Information systems research: Contemporary

approaches & emergent traditions. Amsterdam:

Elsevier.

Chiasson, M., & Dexter, A.S. 2001. System development

conflict during the use of an information systems

prototyping method of action research. Information

Technology & People, 14(1), 91-108.

Chua, W. 1986. Radical developments in accounting

thought. The Accounting Review, 61(4), 601-632.

Davidson, R. M., Martinsons, M. G., & Kock, N. 2004.

Principles of canonical action research. Information

Systems Journal, 14, 65-86.

Davison, R. 2001. Gss and action research in the hong kong

police. I.T. & People, 14(1), 60-77.

Earl, M. J. 1990. Putting it in its place: A polemic for the

nineties Oxford Institute of Information Management.

Oxford: Oxford Institute of Information Management.

Eden, M., & Chisholm, R.F. 1993. Emerging varieties of

action research: Introduction to the special issue.

Human Relations, 46, 121-142.

Fairley, R. 1985. Scientific progress in management

information systems. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Galliers, R. D. 1992. Choosing information systems

research approaches. In R. Galliers (Ed.), Information

systems research - issues, methods and practical

guidelines (pp. 144-162): Alfred Waller Ltd.

Gartner Group. (2008). Gartner clarifies the definition of

the term 'enterprise architecture' (report number

g00156559). Retrieved Aug., 2015, from https://

online.ist.psu.edu/sites/gettingstarted/files/gartnerclarif

ies.pdf

Gartner Research. (2012). It glossary. 2012, from

http://www.gartner.com/technology/it-glossary/

enterprise-architecture.jsp

Harvey, L. 1997. A discourse on ethnography. In A. S. Lee,

J. Liebenau & J. I. I. DeGross (Eds.), Proceedings of

the ifip tc8 wg8.2 on information systems and

qualitative research (pp. 207-224). London: Chapman

& Hall.

Hirschheim, R., & Klein, H.K. 1989. Four paradigms of

information systems development. Communications of

the ACM, 32(10), 1199-1216.

Iacono, S., & Kling, R. 1988. Computer systems as

institutions: Social dimensions of computing in

organisations. In J. I. DeGross & M. H. Olson (Eds.),

Proc. Ninth international conf. On information systems

(pp. 101-110). Minneapolis, MN.

Iivari, J. 1991. A paradigmatic analysis of contemporary

schools of is development. Eur. J. Information Systems,

1(4), 249-272.

Iivari, J., Hirschheim, R., & Klein, H.K. 1998. A

paradigmatic analysis contrasting information systems

development approaches and methodologies.

Information Systems Research, 9(2), 164-193.

ISO/IEC. 2005. Annex a: Geram Iso/is

15704:2000/amd1:2005: Industrial automation

systems - requirements for enterprise-reference

architectures and methodologies.

Jarvenpaa, S. L. 1991. Panning for gold in information

systems research: 'Second-hand' data Information

systems research - issues, methods and practical

guidelines (pp. 63-80): Alfred Waller Ltd.

Jick, T. D. 1979. Mixing qualitative and quantitative

methods: Triangulation in action. Admin. Science

Quarterly, 24(4).

Jönsson, S. 1991. Action research. In H.-E. Nissen, H. K.

Klein & R. Hirschheim (Eds.), Information systems

research: Contemporary approaches and emergent

traditions. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Keen, P. G. W., & Scott Morton, M. 1978. Decision support

systems: An organisational perspective. Reading,

Massachussetts: Addison-Wesley.

Kiecolt, K. J., & Nathan, L. E. 1985. Secondary analysis of

survey data. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publication.

Lapalme, J. 2012. Three schools of thought on enterprise

architecture. IT Professional, 14(6), 37-43.

Lau, F. 1997. A review on the use of action research in

information systems studies. In A. Lee, J. Liebenau &

J. I. DeGross (Eds.), Information systems and

Advancing Research in Enterprise Architecture - An Information Systems Paradigms Approach

547

qualitative research (pp. 31-68). London: Chapman &

Hall.

Lehtinen, E., & Lyytinen, K. 1986. Action based model of

information system. Information Systems Research,

11(4), 299-317.

Lin, A.C. 1998. Bridging positivist and interpretivist

approaches to qualitative methods. Policy Studies

Journal, 26 (1), 162-180.

Lucas, H. C. 1981. Implementation, the key to successful

information systems. New York: Columbia University

Press.

Lundeberg, M., Goldkuhl, G., & Nilsson, A. 1981.

Information systems development: A systematic

approach. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-

Hall.

Markus, M. L. 1983. Power, politics, and mis

implementation. Comm ACM, 26, 430-444.

McGregor, D. 1960. The human side of enterprise. New

York: McGraw-Hill.

McKay, J., & Marshall, P. 2001. The dual imperatives of

action research. Information Technology & People,

14(1), 46-59.

Myers, M. D. 1997. Critical ethnography in information

systems. In A. S. Lee, J. Liebenau & J. I. I. DeGross

(Eds.), Information systems and qualitative research -

proceedings of the ifip tc8 wg8.2 on is and qualitative

research (pp. 276-300). London: Chapman & Hall.

Neumann, D., de Santa-Eulalia, L.A., & Zahn, E. 2011.

Towards a theory of collaborative systems. Paper

presented at the Adaptation and Value Creating

Collaborative Networks (Proceedings of the 12

th

IFIP

Working Conference on Virtual Enterprises - PROVE

11), São Paulo / Brazil.

Noran, O. 2008. A meta-methodology for collaborative

networked organisations: Creating directly applicable

methods for enterprise engineering projects.

Saarbrücken: VDM Verlag Dr. Müller.

Noran, O. 2009. Engineering the sustainable business: An

enterprise architecture approach. In G. Doucet, J. Gotze

& P. Saha (Eds.), Coherency management: Architecting

the enterprise for alignment, agility, and assurance (pp.

179-210): International Enterprise Architecture

Institute.

Noran, O. 2012. Achieving a sustainable interoperability of

standards. Annual Reviews in Control, 36, 327-337.

Noran, O. 2014. Collaborative disaster management: An

interdisciplinary approach. Computers in Industry,

65(6), 1032-1040.

Noran, O., & Panetto, H. 2013. Modelling a sustainable

cooperative healthcare: An interoperability-driven

approach Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 8186,

238-249.

Nurminen, M. I. 1997. Paradigms for sale: Information

systems in the process of radical change. Scandinavian

Journal of Information Systems, 9(1), 25-42.

Pava, C. 1983. Managing new office technology, an

organisational strategy. New York: Free Press.

Sommerville, I. 1989. Software engineering (3rd ed.).

Reading, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley.

Stohr, E. A., & Konsynsky, B. R. 1992. Information

systems and decision processes: IEEE Computer

Society Press.

Swanson, B. E. 1988. Information system implementation,

bridging the gap between design and implementation.

Homewood, Illinois: Irwin.

Trauth, E. M. 1997. Achieving the research goal with

qualitative methods: Lessons learned along the way. In

A. S. Lee, J. Liebenau & J. I. I. DeGross (Eds.),

Information systems and qualitative research -

proceedings of the ifip tc8 wg8.2 on is and qualitative

research (pp. 225-246). London: Chapman & Hall.

Trochim, W. M. (2000). The research methods knowledge

base. Retrieved Aug 2000, 2000, from http://trochim.

human.cornell.edu/kb/index.htm

Wood-Harper, A. T. 1985. Research methods in is: Using

action research. In E. Mumford, R. Hirschheim, G.

Fitzgerald & A. T. Wood-Harper (Eds.), Research

methods in information systems - proceedings of the ifip

wg 8.2 colloquium (pp. 169-191). Amsterdam: North-

Holland.

ICEIS 2016 - 18th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

548