Academics’ Intention to Adopt SNS for Engagement Within Academia

Eleni Dermentzi, Savvas Papagiannidis, Carlos Osorio and Natalia Yannopoulou

Newcastle University Business School, Newcastle University, 5 Barrack Road, Newcastle Upon Tyne, U.K.

Keywords: Academics, Social Media, Academic Engagement, Social Networking Sites, Theory of Planned Behaviour,

Gratifications Theory.

Abstract: Although Social Networking Sites (SNS) have become popular among scholars as tools for engagement

within academia, there is still a need to examine the motives behind academics’ intentions to adopt SNS. This

study proposes and tests a research model based on the Decomposed Theory of Planned Behaviour and

Gratifications Theory with a sample of 370 academics around the world in order to address the objective set.

Our findings suggest that while attitude and perceived behavioural control are the main drivers of academics’

intentions to adopt SNS for engagement, the effect of social norms on intentions is not significant. In addition,

networking needs, perceived usefulness, image, and perceived reciprocity affect attitude, while self-efficacy

affects perceived behavioural control. Implications for SNS providers and universities that want to promote

and encourage online engagement within their faculties are discussed.

1 INTRODUCTION

Online or internet technologies have long been

established as communication and collaboration tools

in academia (Veletsianos and Kimmons, 2012). More

specifically, when it comes to networking and

information sharing, a specific type of online

technology has prevailed over the past few years:

Social Networking Sites (SNS). SNS have been

defined as “web-based services that allow individuals

to (1) construct a public or semi-public profile within

a bounded system, (2) articulate a list of other users

with whom they share a connection, and (3) view and

traverse their list of connections and those made by

others within the system” (Boyd and Ellison, 2007).

Although many of them have not been created for

professional purposes, research has shown that

scholars employ them as professional tools that can

be used beyond instructional purposes (Veletsianos,

2012). SNS can facilitate the creation of social capital

in academia (Madhusudhan, 2012; Richter, 2011) and

make Networked Participatory Scholarship feasible,

which is “the practice of scholars’ use of

participatory technologies and online social

networks to share, reflect upon, critique, improve,

validate, and further their scholarship” (Veletsianos

and Kimmons, 2012). Most importantly, SNS can

help both academics and institutions increase

community outreach, and facilitate their efforts to

create impact on society and their effectiveness in

accomplishing their goals (Forkosh-Baruch and

Hershkovitz, 2012; Veletsianos and Kimmons, 2013).

Due to the significant benefits that SNS can

potentially offer in an academic context, scholars

have begun to examine the use of SNS for academic

purposes more systematically (e.g. Gruzd, Staves, &

Wilk, 2012; Veletsianos and Kimmons, 2012).

However, so far research has focused exclusively on

answering “how” SNS can change academic practice

and “what” the academics’ usage patterns are

(Forkosh-Baruch and Hershkovitz, 2012;

Madhusudhan, 2012; Van Noorden, 2014;

Veletsianos, 2012; Veletsianos and Kimmons, 2012;

Veletsianos and Kimmons, 2013). Our work builds on

this emerging body of research, extending it by

focusing on “why” scholars participate in SNS. To the

best of our knowledge this is the first scholarly article

that attempts to understand the motivating factors that

drive academics to adopt SNS by following a

quantitative approach. Related literature has been of

an exploratory nature so far, using qualitative

approaches (Gruzd, Staves, & Wilk, 2012; Lupton,

2014). In addition, current research is based entirely

upon the views of the actual users of SNS, ignoring

the attitudes of a great number of academics that do

not use SNS. Based on the above, the overall

objective of this paper is to study the academic use of

SNS for engagement, taking into consideration both

Dermentzi, E., Papagiannidis, S., Osorio, C. and Yannopoulou, N.

Academics’ Intention to Adopt SNS for Engagement Within Academia.

In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies (WEBIST 2016) - Volume 1, pages 219-228

ISBN: 978-989-758-186-1

Copyright

c

2016 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

219

users and non-users of SNS. In order to address our

objective, we synthesise and apply the Decomposed

Theory of Planned Behaviour (Decomposed TPB)

and Uses and Gratifications Theory, proposing a

conceptual model that aims to determine the factors

that affect academics’ intention to use SNS in order

to disseminate their research and engage with their

colleagues.

This paper is organised in the following way:

Firstly, we review the related literature and build our

research model. Then, we present our methodology

and the results of our data analysis. Discussion of the

results follows and the paper concludes with a

summary of our results and their implications, the

limitations of our study and directions for future

research.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Theoretical Framework

The Decomposed TPB is an alternative version of the

TPB model proposed by Ajzen (1991). According to

the TPB model, human behaviour is affected by three

factors: a) attitude towards behaviour, b) subjective

or social norm, which is the perceived social pressure,

and c) perceived behavioural control, which is “the

perceived ease or difficulty of performing the

behaviour”. These three factors lead to the

development of behavioural intention (Ajzen,

2002b). In the Decomposed TPB, the three factors are

analysed further by taking apart the various

dimensions that comprise them. Consequently, the

Decomposed TPB provides a more holistic

understanding of behavioural intentions, since the

analysis of the factors renders the relationships

among them clearer and easier to understand and

interpret (Taylor and Todd, 1995).

While the Decomposed TPB is a suitable model

for examining Information Technology (IT) usage

(Taylor and Todd, 1995), it is not specialised on new

media, such as SNS. Hence, the Uses and

Gratifications Theory, which is considered more

appropriate for understanding the uses of new media

by individuals (Foregger, 2008), is also adopted. The

theory sheds light on how individuals use

communications among other resources in order to

meet their needs and accomplish their goals. It is

based on five basic assumptions: a) the audience is

conceived of as active, b) the audience takes a great

deal of initiative in linking “need gratification” and

media choice, c) media compete with other sources of

need satisfaction, d) as far as methodology is

concerned, many of the goals related to mass media

use can be derived from data provided by the

audience itself, and e) judging the cultural

significance of mass communication should be

avoided while audience orientations are separately

explored (Katz et al., 1973).

Based on the Decomposed TPB (Taylor and Todd,

1995) and Uses and Gratifications Theory (Katz et al.,

1973), we propose a research model that investigates

how academics’ intention to use SNS in order to

engage with their peers and create impact within

academia is formed. The section that follows

examines the various factors that may affect attitude

towards behaviour, social norms, perceived

behaviour control and lastly intention.

2.2 Research Model and Development

of Hypotheses

Self- Promotion and Image: One of the needs

related to the use of media, as proposed by the Uses

and Gratifications Theory, is the need to gain insights

into one’s personal identity (Flanagin and Metzger,

2001). Web sites are regularly used for implementing

impression management strategies (i.e. strategies that

aim to control information about a person, an object,

an entity or idea) (Connolly-Ahern and Broadway,

2007). Participation in online communities has also

been connected with self- interest motives, like

seeking to enhance one’s reputation (Faraj and

Johnson, 2010). In the academic context, blogs are

often used as tools for sharing thoughts about

academic work conditions and policies and even

promoting one’s expertise by providing advice

(Mewburn and Thomson, 2013), activities that

eventually result in the creation of a virtual academic

identity. Likewise, SNS have been found to be used

by academics as tools for forming digital identity and

engaging in impression management (Veletsianos,

2012). Many academics seem to use social media in

order to increase the visibility of their research and

discuss their ideas with their colleagues (Lupton,

2014; Menendez, Angeli, & Menestrina, 2012). We

suggest that academics’ need for self-promotion,

which is the manifestation of one’s abilities or

accomplishments in order to be seen as competent by

others (Bolino and Turnley, 1999), and enhancement

of professional identity affect their attitude towards

using online technologies for engagement in a

positive way.

H1. The motive of self- promotion positively

affects academics’ attitude towards using SNS for

academic engagement.

H2. The motive of maintaining a positive image

WEBIST 2016 - 12th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

220

positively affects academics’ attitude towards using

SNS for academic engagement.

Information Sharing and Seeking: Knowledge

management, including information seeking and

sharing is a common motive for using online services.

According to Papacharissi and Rubin (2000),

information seeking is the most salient use of the

Internet. This is especially true for virtual

communities, with online users stating that the main

reason they visit them is the opportunity to exchange

information (Ridings and Gefen, 2004). A more

recent study has found that information seeking is a

motive for using SNS too, as users regard social

relationships as useful sources for information (Kim

et al., 2011). This is in agreement with previous

findings suggesting that information seeking is one of

the four gratifications derived from using SNS (Ku,

Chu, & Tseng, 2013). Interpersonal utility, which

takes the form of information sharing among peers, is

also considered as a motive for Internet use

(Papacharissi and Rubin, 2000). The use of SNS for

information dissemination seems to be the case in

academia, too (Lupton, 2014; Menendez et al., 2012).

More specifically, many academics use SNS in order

to keep in touch with new developments and events

and provide access to new or unpublished articles in

their research field (Lupton, 2014). Therefore, we

propose:

H3. The motive of information sharing positively

affects academics’ attitude towards using SNS for

academic engagement.

H4. The motive of information seeking positively

affects academics’ attitude towards using SNS for

academic engagement.

Networking: Studies about the use of online

communities have shown that many of the ways that

people use to communicate during face-to-face

interactions are replicated in online environments,

with online members seeking social support or

friendships by joining an online community

(Maloney-Krichmar & Preece, 2005; Ridings and

Gefen, 2004). Not surprisingly, one of the main uses

of SNS is networking in the form of maintaining old

ties and creating new ones with peers that share the

same interests (Foregger, 2008; Kim et al., 2011; Ku

et al., 2013). Academics also use SNS for connecting

and establishing networks and sometimes they even

use SNS as platforms for multi-disciplinary

collaborations (Gruzd et al., 2012; Jung and Wei,

2011; Lupton, 2014). We expect that:

H5. The motive of maintaining old contacts

positively affects academics’ attitude towards using

SNS for academic engagement.

H6. The motive of creating new contacts positively

affects academics’ attitude towards using SNS for

academic engagement.

Perceived Usefulness: Perceived usefulness has

been defined as “the degree to which a person

believes that using a particular system would enhance

his or her job performance” (Davis, 1989). According

to Taylor and Todd (1995), who tested the predictive

power of the Decomposed TPB, perceived usefulness

is significantly related to attitude. Research that

examines participation in virtual communities (Lin,

2006) has also found that the path from perceived

usefulness to attitude is significant. Online tools are

often considered useful by scholars for organising

their work and increasing their efficiency (Lupton,

2014). The above lead us to the following hypothesis:

H7. Perceived usefulness of SNS positively affects

academics’ attitude towards using SNS for academic

engagement.

Perceived Trust: In this study, perceived trust

refers to the trust an individual has in the benevolence

and integrity of other online users (Lin, 2006). Trust

has been considered as a factor influencing

participation in virtual communities and social

interactions that take place in them (Chiu et al., 2006).

Lin (2006) found that perceived trust is one of the

determinants of member intentions to participate in

virtual communities. In fact, the prosperity of an

online community is based on members’ sense of

trust that the other members will treat them with

respect and care (Maloney-Krichmar and Preece,

2005). Moreover, trust has been found to play an

important role in using SNS for online political

participation. In the study of Himelboim et al. (2012),

people who reported trusting others were more likely

to use SNS for political interaction and search of

political information. Absence of trust could

discourage participation in SNS, especially when

academics are concerned about being vulnerable to

various types of attack online, including outright

aggression, hate speech or harassment (Lupton,

2014). For these reasons we propose that:

H8. Perceived trust among SNS members

positively affects academics’ attitude towards using

SNS for academic engagement.

Perceived Reciprocity: Reciprocity is a “give

and take” exchange relationship that can appear in

online environments, with the users helping each

other and rewarding kind actions. Chiu et al. (2006)

have found that there is a positive and significant

relationship between reciprocity and the quantity of

knowledge sharing in virtual communities. Likewise,

Jeon et al. (2011) have found that reciprocity has a

positive effect on members’ attitudes toward

knowledge sharing in communities of practice. Long-

Academics’ Intention to Adopt SNS for Engagement Within Academia

221

lasting sustainable online communities are

characterised by strong group norms of support and

reciprocity that make even externally driven

governance unnecessary (Faraj and Johnson, 2010;

Maloney-Krichmar and Preece, 2005). Giving and

receiving support is one of the perceived benefits

academics may gain by joining SNS (Lupton, 2014).

We postulate that:

H9. Perceived reciprocity in SNS positively

affects academics’ attitude towards using SNS for

academic engagement.

Peer and External Influence: As the

Decomposed TPB suggests, social norms are affected

by peer influence, which takes the form of

encouragement or opposition towards using the IT in

question (Taylor and Todd, 1995). Hsu and Chiu

(2004) have added an additional factor, namely

“external influence”, which is the influence by mass

media, experts and any other non-personal

information that could affect individuals’

considerations about performing the behaviour. The

research of Bhattacherjee (2000) confirms that

external influence is an important determinant of

social norms in IT related contexts. Academics seem

to take into consideration their colleagues’ opinion

about SNS, even if these opinions come from

academics outside their home organisation or from a

different discipline (Gruzd et al., 2012). Based on the

above, the following hypotheses are put forward:

H10. Peer influence positively affects the social

norms of academics.

H11. External influence positively affects the

social norms of academics.

Privacy Control: Privacy control involves the

ability of academics to control information about

themselves and their research in online environments.

For example, as far as SNS are concerned, privacy

control could be influenced by the privacy policy of

SNS, the awareness that information is being

collected, the voluntary character of the information

submission, and the openness of information usage by

the SNS (Xu et al., 2013). So far, privacy control has

been associated with the alleviation of privacy

concerns in SNS (Xu et al., 2013) and Internet use

(Dinev and Hart, 2003). In the case of academics,

these concerns are about privacy in general, inability

to control the content posted on social media and

copyright issues (Gruzd et al., 2012; Lupton, 2014).

Ajzen (2002b) has introduced the general notion of

controllability as the second factor that, along with

self-efficacy, comprises the perceived behavioural

control in the TPB model. We hypothesise that:

H12. Privacy control in SNS positively affects

theperceived behavioural control of academics.

Self-efficacy: In the context of online

technologies, self-efficacy refers to users’ beliefs in

their capabilities to use online technologies. Lack of

technological proficiency can be an important barrier

to knowledge sharing in online communities

(Ardichvili, 2008). The Decomposed TPB suggests

that self-efficacy is one of the determinants of

perceived behavioural control (Taylor and Todd,

1995). This notion is also supported by research in the

e-commerce field that found that self-efficacy

influences perceived behavioural control

significantly (Hung et al., 2003). Although academics

are sufficiently technologically competent since they

have to use the Internet in their academic practice

(e.g. getting access to academic journals, submitting

manuscripts through journals’ online systems etc.),

they still may feel that they have difficulties in

managing personal and professional information

when they use new online tools like SNS (Gruzd et

al., 2012). We therefore expect that:

H13. Self-efficacy related to the use of SNS

positively affects the perceived behavioural control of

academics.

Attitude, Social Norms and Perceived

Behaviour Control: According to the Decomposed

TPB (Taylor and Todd, 1995) and the original TPB

(Ajzen, 1991), behaviour is a direct function of

behavioural intention. One of the main factors that

affects behavioural intention according to Ajzen

(1991) is the attitude towards behaviour, or in other

words, whether a person is in favour of or against the

behaviour in question. Research on social networking

has shown that attitude toward social networking is

positively associated with intention to use social

networking (Peslak et al., 2011). Similarly, social (or

subjective) norms, which is the second factor that

affects behavioural intention in TPB, is found to be

positively correlated to intention in an SNS context

(Peslak et al., 2011). Finally, perceived behavioural

control has also been found to have a positive

relationship with intention in a similar context, that of

participating in virtual communities (Lin, 2006). Based

on the above, the following hypotheses are formulated:

H14. Attitude of academics towards using SNS for

academic engagement positively affects intention to

use SNS for this purpose.

H15. Social norms of academics related to using

SNS for academic engagement positively affect

intention to use SNS for this purpose.

H16. Perceived behavioural control of academics

related to using SNS for academic engagement

positively affects intention to use SNS for this

purpose.

WEBIST 2016 - 12th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

222

3 METHODOLOGY

For the purposes of the study a purposeful sample that

covers academics (including doctoral students) from

different disciplines, career stages and countries was

employed. In order to achieve this we used different

sampling techniques: a) we distributed the survey’s

link via social networking sites, by posting it on

groups with an academic focus and using our personal

profiles on Twitter, Academia.edu etc. b) we created

a random sample of 3000 academics and we sent the

survey’s link through email invitations. Since there is

no list of academics around the world, we chose

universities at random from the list of universities

around the world provided by Webometrics

(www.webometrics.info) and we retrieved contact

information about random academics from

universities’ webpages. A total of 711 respondents

started the survey. After discarding the incomplete

responses and outliers, the remaining 370 valid

responses were used for our analysis. Table 1 shows

the profiles of the participants.

The online questionnaire that was used in the

study was constructed by following the main

premises of the two main theories suggested (Ajzen,

2002a; Francis et al., 2004; Katz et al., 1973). Table 2

presents the sources from which items were adapted.

4 ANALYSIS AND RESULTS

4.1 Reliability and Validity

We ran both Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) and

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) in order to

assess the construct reliability and validity. The

Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) and principal

component factor analysis were conducted to

examine the adequacy of the study sample and the

validity of the study instrument, respectively. After

removing some items due to poor loadings or failure

to load with the expected factor, we found that the

value of KMO was 0.943 and all the items loaded on

each distinct factor and explained 83.49% of the total

variance. The reliability of the scales was also tested

and the Cronbach’s alphas of all scales ranged between

0.741 and 0.965 (Table 2), indicating very good

Table 1: Sample Demographics (N=370).

Percent Percent

Age

Area

18 - 24 0.8 Europe 76.1

25 - 34 28.6 America 10.3

35 - 44 33.8 Asia 6.5

45 - 54 19.5 Australia/Oceania 6.8

55 - 64 14.6 Africa 0.3

Current Post

Discipline Group

PhD student 17.5 STEM 24.6

Post Doc/Research Associate 8.1 Humanities 9.7

Lecturer 21.9 Social Sciences 58.1

Senior Lecturer/Assistant Prof. 27.6 Multidisciplinary 7.6

Reader/Associate Prof./Prof. 24.9

Gender

Experience

Male 54.6

1 – 5 15.5 Female 45.4

6 – 10 30.5

SNS User

11 – 20 35.1 Yes 82.2

21 – 30 12.1 No 17.8

31 and over 6.8

Engage via SNS

60.0

Not engaging via SNS

40.0

Table 2: Cronbach's a.

Variable Cronbach’s a Variable Cronbach’s a

Intention (Ajzen 2002b; Lin 2006) 0.965 Perc. Usefulness (Lin 2006) 0.939

Attitude (Peslak et al. 2011) 0.942 Image (Moore and Benbasat 1991) 0.937

Subj. Norms (Lin 2006; Taylor and Todd 1995) 0.943 Trust (Chiu et al. 2006) 0.917

PBC (Lin 2006; Taylor and Todd 1995) 0.741 Peer Influence(Taylor and Todd 1995) 0.945

Privacy Control (Xu et al. 2013) 0.930 External Influence(Hsu and Chiu 2004) 0.902

Old Ties (Foregger 2008) 0.896 Reciprocity (Chiu et al. 2006) 0.886

New Contacts (Kim et al. 2011) 0.911 Self-Efficacy (Lin 2006) 0.910

Info Seek (Kim et al. 2011) 0.918 Self-Promotion(Bolino and Turnley 1999) 0.925

Info Share (Papacharissi and Rubin 2000) 0.804

Academics’ Intention to Adopt SNS for Engagement Within Academia

223

reliability according to Fornell and Larcker (1981).

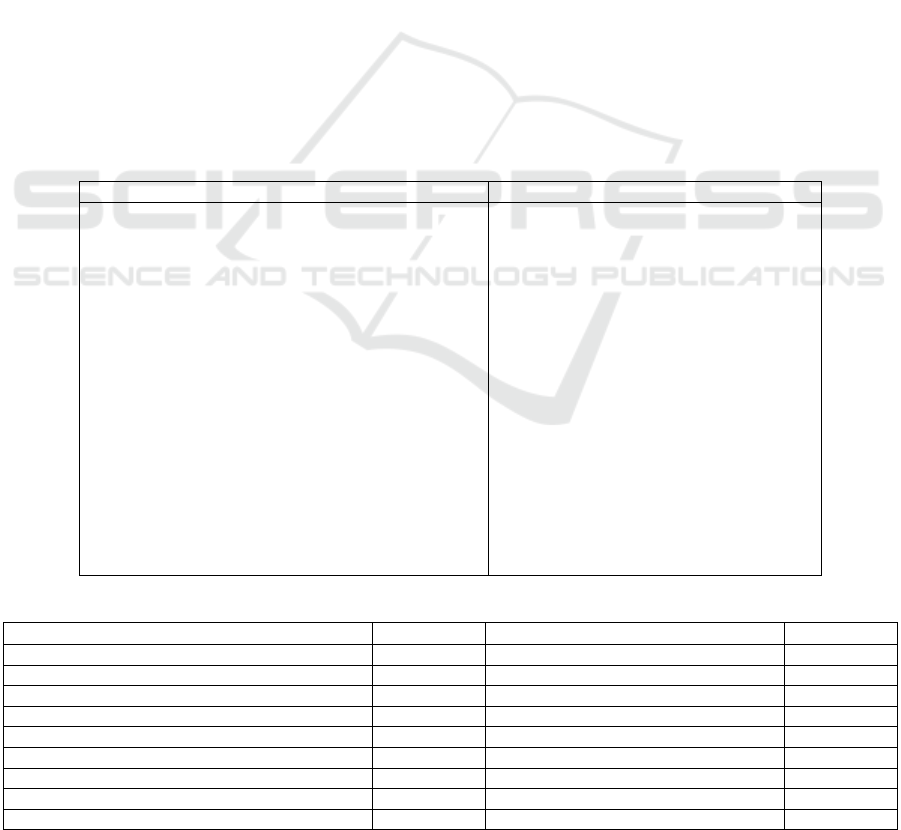

We further tested construct reliability and validity

by conducting CFA using the AMOS software

package. As can be seen in Figure 1, all the constructs

have Composite Reliabilities (CR) above the

recommended value of 0.70 and the Average

Variance Extracted exceeds the threshold of 0.50

(Hair et al. 2014) and therefore reliability and

convergent validity have been established. In

addition, the square root of AVE is greater than inter-

construct correlations for every construct; thus, there

is discriminant validity among them.

According to Hair et al. (2014), when the number

of observations is above 250 and the model contains

more than 30 observed variables, significant p-values

are expected for χ

2

and a good model fit has been

established when CFI is above 0.90, SRMR is 0.08 or

less and RMSEA is less than 0.07. Our measurement

model meets all the above thresholds (χ

2

/df = 1.683,

CFI = 0.95, SRMR = 0.0517, RMSEA = 0.043),

demonstrating a good model fit.

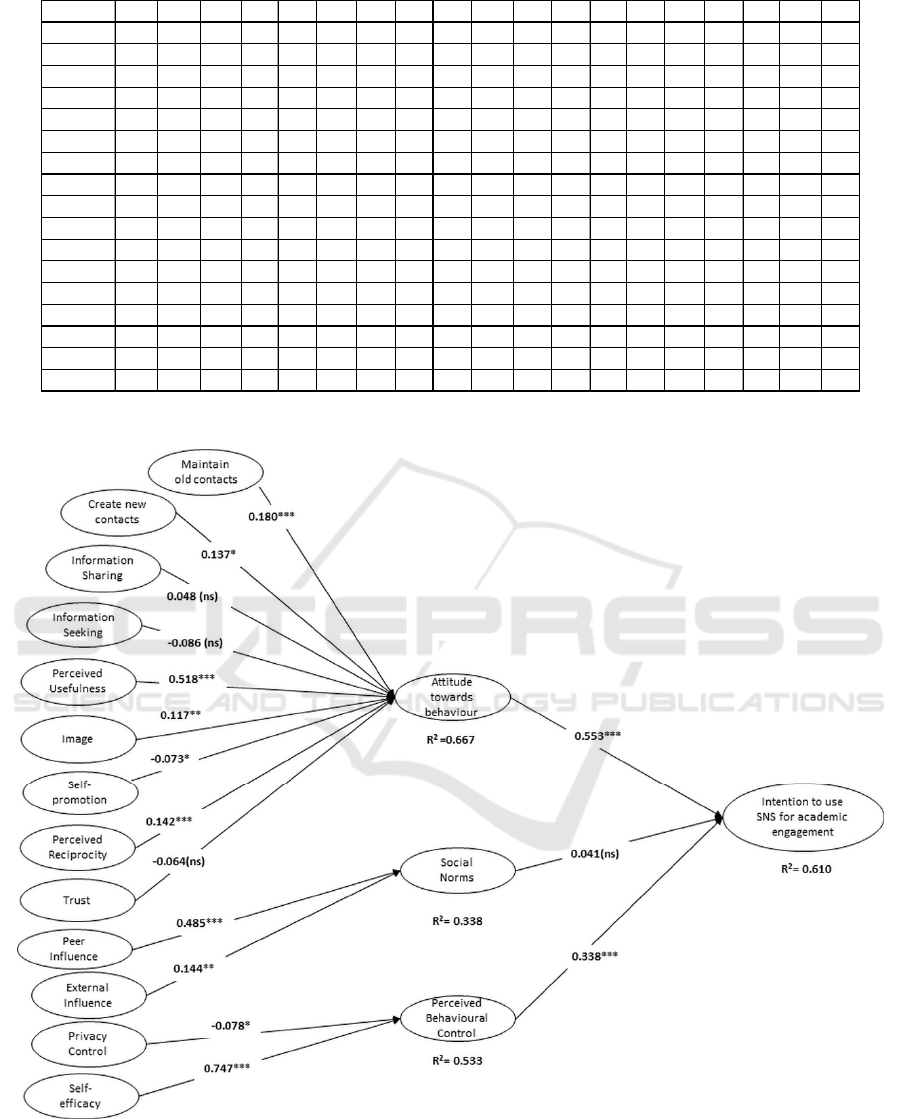

4.2 Structural Model

After testing our full hybrid model (χ2/df =1.794, CFI

= 0.94, SRMR = 0.0714, RMSEA = 0.046), we

obtained the results that are presented in Figure 2.

According to the results, maintaining old contacts

(β = 0.180, p<0.01), creating new contacts (β= 0.137,

p<0.1), perceived usefulness (β= 0.518, p<0.01),

image (β= 0.117, p<0.05), and reciprocity (β=0.142,

p<0.01) had a positive effect on attitude towards

using SNS for academic engagement and therefore

H5, H6, H7, H2 and H9 were supported. Self-

promotion, on the other hand, had a slightly negative

effect (β= -0.073, p<0.1) on attitude and thus H1 was

rejected. Information seeking, information sharing

and perceived trust had non- significant effects on

attitude and therefore H4, H3 and H8 were rejected as

well. Peer influence (β=0.485, p<0.01) and external

influence (β=0.144, p<0.05) had positive effects on

social norms, and thereby H10 and H11 were

supported. While self-efficacy (β= 0.747, p<0.01) had

a significant positive effect on perceived behaviour

control, the effect of privacy control (β=-0.078,

p<0.1) was slightly negative and therefore only H13

was supported, whereas H12 was rejected. Finally,

H14 and H16 were supported as attitude (β=0.553,

p<0.01) and perceived behaviour control (β= 0.338,

p<0.01) affected intention to use SNS for academic

engagement positively. H15, however, was rejected

as the effect of social norms on intention was not

significant.

5 DISCUSSION

The aim of this study is to understand the factors that

motivate academics to use SNS in order to engage

with their peers and augment the impact of their

research. Ten out of the sixteen hypotheses were

supported based on the data analysis. Not

surprisingly, attitude towards SNS use for

engagement was found to have a strong and

significant effect on the intention of academics to use

such platforms for professional purposes. Similarly,

perceived behaviour control of SNS use affects the

intention to use them positively, a finding that is in

line with the expectations of TPB. In addition, there

were high levels of explained variance in these three

constructs (R

I

2

= 0.610, R

A

2

=0.667 and R

PBC

2

=

0.533). Social norms, on the other hand, do not have

any significant effect on intention. This is not

completely unexpected. Lin (2006), who looked into

the intention to participate in virtual communities,

found that social norms do not influence behavioural

intention. In addition, according to Taylor and Todd

(1995), it is not uncommon for studies using TAM

and TPB theories to find no significant influence of

social norms on behavioural intention. In fact, social

norms have been found to be more influential in

organisational settings and when respondents have

little experience with the technology under

examination. According to the demographics of our

sample the vast majority of the respondents already

use SNS for various reasons (82.2%), so they cannot

be considered as inexperienced users.

Another interesting finding is that the effects of

information sharing and information seeking on

attitude are not significant. A possible explanation is

that academics, being used to seeking and sharing

information through more formal and reliable

sources, such as journals and books, do not consider

SNS as potential channels for information exchange,

and therefore such motives do not affect their

attitudes towards using SNS for engagement.

Concerns about lack of credibility, the quality of

posted content and copyright issues, which have been

expressed in the study of Lupton (2014) regarding

SNS use by scholars, could explain the reluctance of

academics to consider SNS as important sources of

academic information. This could also explain the

non-significant effect of perceived trust on attitude. If

academics believe that SNS are not appropriate

environments for exchanging academic information,

trust should not be of such importance since the risks

associated with the concerns discussed above are not

present. Another potential explanation could be that

academics already know many of their peers in their

WEBIST 2016 - 12th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

224

Figure 1: Construct Correlation Matrix (Square root of AVE on the diagonal).

Figure 2: Results of SEM analysis (Note: * p< 0.1, **p<0.05, ***p<0.01, ns= not significant).

subject area prior to connecting to them online, thus

trust is taken for granted and does not affect their

attitudes towards SNS use for engagement within

academia.

A limited information exchange among

academics on SNS could also justify the fact that

CR AVE 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17

InfoSeek 0.920 0.744 0.862

Attitude 0.943 0.768 0.628 0.876

SocialNorm 0.944 0.893 0.521 0.498 0.945

PBC 0.772 0.638 0.577 0.733 0.466 0.799

OldTies 0.898 0.640 0.567 0.582 0.411 0.556 0.800

NewContac 0.912 0.776 0.781 0.646 0.460 0.551 0.617 0.881

Usefulness 0.941 0.842 0.748 0.771 0.499 0.684 0.582 0.711 0.917

Image 0.932 0.735 0.520 0.521 0.530 0.417 0.365 0.492 0.547 0.857

SelfPromo 0.923 0.708 0.418 0.350 0.331 0.366 0.416 0.492 0.443 0.403 0.842

Reciprocity 0.886 0.796 0.483 0.537 0.430 0.497 0.357 0.499 0.560 0.473 0.316 0.892

Trust 0.914 0.682 0.343 0.320 0.310 0.261 0.316 0.368 0.343 0.484 0.272 0.544 0.826

PeerInflue

n

0.945 0.896 0.380 0.281 0.563 0.368 0.289 0.329 0.408 0.515 0.288 0.440 0.309 0.947

ExternalInfl 0.905 0.706 0.396 0.282 0.412 0.357 0.303 0.362 0.370 0.500 0.232 0.489 0.427 0.584 0.840

PrivacyCntr 0.927 0.761 0.180 0.208 0.216 0.126 0.230 0.243 0.193 0.199 0.156 0.207 0.440 0.145 0.279 0.873

SelfEfficacy 0.896 0.684 0.588 0.677 0.393 0.676 0.494 0.576 0.695 0.473 0.394 0.721 0.461 0.411 0.400 0.266 0.827

Intention 0.967 0.908 0.534 0.764 0.439 0.709 0.527 0.609 0.686 0.437 0.379 0.498 0.295 0.304 0.284 0.132 0.608 0.953

InfoShare 0.810 0.682 0.820 0.636 0.421 0.513 0.568 0.751 0.740 0.488 0.382 0.509 0.391 0.350 0.362 0.158 0.620 0.518 0.826

Academics’ Intention to Adopt SNS for Engagement Within Academia

225

privacy control has a slight negative effect on

perceived behaviour control. Indeed, it has been

found that privacy concerns and information sharing

on SNS are related, with privacy concerns having a

negative effect on self-disclosure of personal

information (Xu et al., 2013). It would be normal for

academics to consider privacy control as a relatively

unimportant factor of the overall control they believe

they have over their SNS use, if they do not disclose

any sensitive or significant information.

Finally, the self-promotion motive has a small but

negative effect on attitude towards SNS use for

academic engagement. This could be attributed to the

different attitudes that male and female academics

hold about self-promotion. Female academics have

been found to be reluctant to engage in self-

promotion activities, in contrast to their male

counterparts (Bagilhole and Goode, 2001; Coate and

Howson, 2014). If this is true, female respondents are

expected to hold an indifferent or even negative

stance towards using SNS for self-promotion.

Further research could also investigate whether there

are differences in academics' attitudes towards self-

promotion based on the discipline.

6 CONCLUSIONS

The present study contributes to the body of

knowledge about engagement and impact in

academia by examining the factors that affect

academics’ intentions to use SNS as a part of their

academic practice. We found that academics’ attitude

and perceived behavioural control regarding SNS use

for academic engagement are the main drivers of

academics’ intentions to adopt SNS for this purpose.

Attitude is mainly influenced by the perceived

usefulness of SNS and secondarily, by a sense of

reciprocity that characterises connections on SNS and

needs for networking and enhancing one’s

professional image. Self-efficacy regarding the use of

SNS for professional reasons is the main driver of

perceived behavioural control. Contrary to what was

expected based on the Decomposed Theory of

Planned Behaviour, social norms do not have

significant effects on academics’ intention to adopt

SNS.

One of the main implications of our study is that

our findings can help academic SNS providers, such

as Academia.edu and ResearchGate understand the

needs of their members and design more efficient

services. As networking and collaboration among

members are the main factors that influence

academics’ attitude towards SNS, they could focus on

the creation of new innovative online services that

enhance the networking experience on their

platforms. In addition, marketing approaches that

stress the actual benefits that an academic can gain by

using SNS could prove to be more efficient in the

recruitment of new members than approaches that

encourage academics to join a social network because

their peers are already members.

An equally important implication is that

universities can use the results of the study to design

more successful online engagement campaigns. As

academics are the ones that undertake research and

create impact it is important that they get involved in

the general process of their institution’s engagement

attempts with other researchers and the public.

Providing training and support on SNS use could be

really helpful since self-efficacy has been found to

play a crucial role in academics’ perceived behaviour

control. In addition, associating the use of SNS for

academic engagement with a professional image that

is desirable in academia and recognising online

engagement activities as a part of the formal

academic practice would probably result in more

academics adopting social media for professional

reasons.

The study has presented our early findings based

on our preliminary analysis Further analysis could

explore whether there are differences among personal

and professional attributes (for instance gender or the

stage at which one is, e.g. comparing early academics

vs. established academics). It will be also of interest

to explore whether there are any significant

differences between those users already engaged on

social media and how satisfied they are overall and

those who are not. With regard to this study’s

limitations, due to the specific context on which our

research focuses, asking questions that capture actual

use was deemed unfeasible. Although we were able

to capture the general actual use of SNS by asking

respondents to self-report the time they spend on

them, specific questions about the time spent on SNS

solely for engaging with other academics were

considered too complicated. This is due to the fact

that most academics do not consciously separate the

time they spend on SNS for engagement purposes

from the time they spend on SNS for other reasons.

Consequently, our model accounts only for intentions

and not for actual use.

Finally, the generalisability of our findings may

be limited due to the demographics of our sample.

Although special attention has been paid to including

academics from different countries, levels of

experience and disciplines, the majority of our

respondents work in universities in Europe and

WEBIST 2016 - 12th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

226

almost half our sample comes from the social

sciences. Using the results of this study to understand

academics’ motives from other disciplines and/or

geographical areas should be done with caution.

REFERENCES

Ajzen, I., 1991. The theory of planned behaviour.

Organizational Behavior and Human Decision

Processes. 50(2). p. 179-211.

Ajzen, I., 2002a. Constructing a TPB questionnaire:

Conceptual and methodological considerations. In

Working paper.

Ajzen, I., 2002b. Perceived Behavioral Control, Self-

Efficacy, Locus of Control, and the Theory of Planned

Behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 32(4).

p. 665-683.

Ardichvili, A., 2008. Learning and Knowledge Sharing in

Virtual Communities of Practice: Motivators, Barriers,

and Enablers. Advances in Developing Human

Resources. 10(4). p. 541-554.

Bagilhole, B., & Goode, J., 2001. The Contradiction of the

Myth of Individual Merit, and the Reality of a

Patriarchal Support System in Academic Careers: A

Feminist Investigation. European Journal of Women’s

Studies. 8(2), p. 161–180.

Bhattacherjee, A., 2000. Acceptance of e-commerce

services: the case of electronic brokerages. Systems,

Man and Cybernetics, Part A: Systems and Humans,

IEEE Transactions on. 30(4). p. 411-420.

Bolino, M. C. and Turnley, W. H., 1999. Measuring

Impression Management in Organizations: A Scale

Development Based on the Jones and Pittman

Taxonomy. Organizational Research Methods. 2(2). p.

187-206.

Boyd, D. M. and Ellison, N. B, 2007. Social Network Sites:

Definition, History, and Scholarship. Journal of

Computer-Mediated Communication. 13(1). p. 210-

230.

Chiu, C.-M., Hsu, M.-H. and Wang, E. T. G., 2006.

Understanding knowledge sharing in virtual

communities: An integration of social capital and social

cognitive theories. Decision Support Systems. 42(3). p.

1872-1888.

Coate, K., & Howson, C. K., 2014. Indicators of esteem:

gender and prestige in academic work. British Journal

of Sociology of Education. pp. 1–19.

Connolly-Ahern, C. and Broadway, S. C., 2007. The

importance of appearing competent: An analysis of

corporate impression management strategies on the

World Wide Web. Public Relations Review. 33(3). p.

343-345.

Davis, F. D., 1989. Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease

of Use, and User Acceptance of Information

Technology. MIS Quarterly. 13(3). p. 319-340.

Dinev, T. and Hart, P., 2003. Privacy Concerns and Internet

Use- A Model of Trade-Off Factors. Academy of

Management Proceedings. 2003(1). p. D1-D6.

Faraj, S., Johnson, S.L., 2010. Network Exchange Patterns

in Online Communities. Organization Science. 22(6).

p. 1464–1480.

Flanagin, A. J. and Metzger, M. J., 2001. Internet use in the

contemporary media environment. Human

Communication Research. 27(1). p. 153-181.

Foregger, S. K., 2008. Uses and Gratifications of

Facebook.com. Unpublished thesis (PhD). Michigan

State University.

Forkosh-Baruch, A. and Hershkovitz, A., 2012. A case

study of Israeli higher-education institutes sharing

scholarly information with the community via social

networks. The Internet and Higher Education. 15(1). p.

58-68.

Fornell, C., Larcker, D.F., 1981. Evaluating structural

equation models with unobservable variables and

measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research.

18(1). p. 39-50.

Francis, J., Eccles, M. P., Johnston, M., Walker, A. E.,

Grimshaw, J. M., Foy, R., … and Bonetti, D., 2004.

Constructing questionnaires based on the theory of

planned behaviour: A manual for health services

researchers. Newcastle upon Tyne, UK: University of

Newcastle upon Tyne.

Gruzd, A., Staves, K., Wilk, A., 2012. Connected scholars:

Examining the role of social media in research practices

of faculty using the UTAUT model. Computers in

Human Behavior. 28(6). p. 2340–2350.

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E.,

2014. Multivariate Data Analysis. Essex, UK: Pearson,

7

th

edition.

Himelboim, I., Lariscy, R. W., Tinkham, S. F., & Sweetser,

K. D., 2012. Social Media and Online Political

Communication: The Role of Interpersonal

Informational Trust and Openness. Journal of

Broadcasting & Electronic Media. 56(1). p. 92–115.

Hsu, M.-H. and Chiu, C.-M., 2004. Predicting electronic

service continuance with a decomposed theory of

planned behaviour. Behaviour & Information

Technology. 23(5). p. 359-373.

Hung, S.-Y., Ku, C.-Y. and Chang, C.-M., 2003. Critical

factors of WAP services adoption: an empirical study.

Electronic Commerce Research and Applications. 2(1).

p. 42-60.

Jeon, S., Kim, Y. G. and Koh, J., 2011. An integrative

model for knowledge sharing in communities-of-

practice. Journal of Knowledge Management. 15(2). p.

251-269.

Jung, S.O., Wei, J., 2011. Groups in academic social

networking services: An exploration of their potential

as a platform for multi-disciplinary collaboration. In

Proceedings of 2011 IEEE International Conference on

Privacy, Security, Risk and Trust and IEEE

International Conference on Social Computing,

PASSAT/SocialCom 2011. p. 545–548.

Katz, E., Blumler, J. G. and Gurevitch, M., 1973. Uses and

Gratifications Research. The Public Opinion Quarterly.

37(4). p. 509-523.

Kim, Y., Sohn, D. and Choi, S. M., 2011. Cultural

difference in motivations for using social network sites:

Academics’ Intention to Adopt SNS for Engagement Within Academia

227

A comparative study of American and Korean college

students. Computers in Human Behavior. 27(1). p. 365-

372.

Ku, Y.-C., Chu, T.-H., Tseng, C.-H., 2013. Gratifications

for using CMC technologies: A comparison among

SNS, IM, and e-mail. Computers in Human Behavior.

29(1). p. 226–234.

Lin, H. F., 2006. Understanding behavioral intention to

participate in virtual communities. Cyberpsychology

Behavior. 9(5). p. 540-547.

Lupton, D., 2014. Feeling Better Connected: Academics’

Use of Social Media, Canberra: News & Media

Research Centre, University of Canberra.

Madhusudhan, M., 2012. Use of social networking sites by

research scholars of the University of Delhi: A study.

The International Information & Library Review.

44(2). p. 100-113.

Maloney-Krichmar, D., Preece, J., 2005. A multilevel

analysis of sociability, usability, and community

dynamics in an online health community. ACM

Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction. 12(2).

p. 201–232.

Menendez, M., Angeli, A. de, Menestrina, Z., 2012.

Exploring the Virtual Space of Academia. In: Dugdale,

J., Masclet, C., Grasso, M.A., Boujut, J.-F., Hassanaly,

P. (Eds.), From Research to Practice in the Design of

Cooperative Systems: Results and Open Challenges.

Springer London. p. 49–63.

Mewburn, I., Thomson, P., 2013. Why do academics blog?

An analysis of audiences, purposes and challenges.

Studies in Higher Education. 38(8). p. 1105–1119.

Moore, G.C., Benbasat, I., 1991. Development of an

Instrument to Measure the Perceptions of Adopting an

Information Technology Innovation. Information

Systems Research. 2(3). p. 192–222.

Papacharissi, Z. and Rubin, A. M., 2000. Predictors of

Internet Use. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic

Media. 44(2). p. 175-196.

Peslak, A., Ceccucci, W. and Sendall, P., 2011. An

Empirical Study of Social Networking Behavior Using

Theory of Reasoned Action. In Proceedings of 2011

CONISAR: Conference for Information Systems

Applied Research, Wilmington North Carolina, USA.

Richter, D., 2011. Supporting virtual research teams - How

social network sites could contribute to the emergence

of necessary social capital. In Proceedings of 15th

Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems:

Quality Research in Pacific, PACIS 2011, paper156.

Ridings, C.M., Gefen, D., 2004. Virtual Community

Attraction: Why People Hang Out Online. Journal of

Computer-Mediated Communication. 10(1).

Taylor, S. and Todd, P. A., 1995. Understanding

Information Technology Usage: A Test of Competing

Models. Information Systems Research. 6(2). p. 144-

176.

Van Noorden, R., 2014. Online collaboration: Scientists

and the social network. Nature News. p. 126–129.

Veletsianos, G., 2012. Higher education scholars'

participation and practices on Twitter. Journal of

Computer Assisted Learning. 28(4). p. 336-349.

Veletsianos, G. and Kimmons, R., 2012. Networked

Participatory Scholarship: Emergent techno-cultural

pressures toward open and digital scholarship in online

networks. Computers & Education. 58(2). p. 766-774.

Veletsianos, G. and Kimmons, R., 2013. Scholars and

faculty members' lived experiences in online social

networks. The Internet and Higher Education. 16(0). p.

43-50.

Xu, F., Michael, K. and Chen, X., 2013. Factors affecting

privacy disclosure on social network sites: an integrated

model. Electronic Commerce Research. 13(2). p. 151-

168.

WEBIST 2016 - 12th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

228