A Real-World Case Scenario in Business Process Modelling for Home

Healthcare Processes

Latifa Ilahi

1

, Sonia Ayachi Ghannouchi

1

and Ricardo Martinho

2,3

1

RIADI Laboratory - National School of Computer Science, University of Manouba, Manouba, Tunisia

2

CINTESIS, FMUP, University of Porto, Porto, Portugal

3

ESTG, Polytechnic Institute of Leiria, Leiria, Portugal

Keywords: Home Healthcare, BPM, BPMN, Tunisia, Real World Case Scenario.

Abstract: Organizations strive to improve the quality of provided services to their customers by making efficient use

of Business Process Management (BPM). Home healthcare structures are considered as an enabler for

linking daily life of patients with Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs). BPM relies first on

business process model specifications that capture the desired workflows in the organization and how

exceptional conditions should be handled. Home healthcare is still less developed in Tunisia than in other

countries such as Canada, United States, Australia, France and Italy. This is due to many reasons, being one

of the most relevant the expensive cost of hospitalization at home with no support from health insurances. In

addition, it is badly organized, with many ad-hoc processes, making them hard to implement and improve.

In this paper, we assess a real-world case scenario of home healthcare in Tunisia through interviews with

involved actors in a private clinic. Also, we present the derived process models of home healthcare for this

case. Our main goal is to have a sound starting point for the BPM cycle, by accurately modelling all

business processes involved in home healthcare. With these models, we intent to: 1) optimize the processes

by automating and rationalizing some activities, 2) implement them in a Business Process Management

System (BPMS), 3) execute them, and 4) improve them through instance harvesting and remodeling.

1 INTRODUCTION

The healthcare domain holds one of the world's

largest hybrid organizations (Ilahi et al., 2014). In

fact, the increased life expectancy leads to a more

than proportionate increase of people called

"fragile", which may suffer from chronic diseases,

are not autonomous and need assistance with the

direct consequence of increased costs of care and

hospitalization. Governments and health insurance

companies are sensitized by such conditions.

Accordingly, the establishment of an efficient

logistics support for these people becomes a

necessity. In this context, many economic, public

and private actors are seeking solutions to maintain

the quality of healthcare system ensuring lower cost.

One of the options for that is the transfer of some

hospital care to home (Zefouni, 2012 and FNEHAD,

2009). Indeed, this focus is interesting from both

social (for instance, ensuring a degree of autonomy

to the elderly and respect their wishes to be treated

at home and close to their families) and financial

aspects (including the high costs of hospitalization

or living in special homes).

However, continuity and collaboration problems

of care remain and persist. These problems have

already been emphasized by several works (Kun,

2001 and Bricon-Souf et al., 2005). We could

observe them in our home healthcare processes case

study, where continuity and collaboration are

ensured in an unorganized manner, and need more

improvements.

From 2014’s demographic statistics (INS, 2014)

about aging of Tunisian population, life expectancy

is around 80 years. Tunisia now has 11% of the

population over 60 years. People aged over 75 years

already represent 8.6% of the population, and they

will almost double in ten years.

As we have found, care collaboration is one of

the major challenges of home healthcare. The

technologies of Business Process Management

(BPM) and, more specifically, the design (modeling)

aspect, are known to typically offer collaboration

support by information technologies. The aim of this

166

Ilahi, L., Ghannouchi, S. and Martinho, R.

A Real-World Case Scenario in Business Process Modelling for Home Healthcare Processes.

DOI: 10.5220/0005654301660174

In Proceedings of the 9th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2016) - Volume 5: HEALTHINF, pages 166-174

ISBN: 978-989-758-170-0

Copyright

c

2016 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

research work is to elicit process models of home

healthcare in a Tunisian private clinic, since there is

no supported home healthcare in the public sector.

Also, we present some of Business Process

Modeling (BPMo) challenges specifically focusing

on home healthcare processes. This is in order to be

able to begin the Business Process Management

(BPM) cycle. For this, we performed interviews with

involved actors to design main home healthcare

processes carried out in Tunisia. We could also

benefit from our previous experiences in modeling

telemedicine processes (Ilahi and Ghannouchi, 2013

and Ilahi et al., 2014).

The remainder of this paper is organized as

follows: Section II describes the basic concepts

regarding home healthcare. Section III highlights

BPM for home healthcare. Section IV describes our

case study in Tunisia of home healthcare processes,

along with the associated process models. Section V

presents our next research steps and, finally, in

section VI, we present main conclusions.

2 HOME HEALTHCARE

Home healthcare is a system of care provided by

skilled practitioners to patients in their homes under

the direction of a physician. Home healthcare

services include nursing care; physical,

occupational, and speech-language therapy; and

medical social services (Bachouch, 2010).

Home healthcare has grown into a vital source of

healthcare, especially for older adults, who represent

72% of recipients (Redjem, 2013). It represents a

very open term and may cover every treatment at

home: from basic home healthcare to advanced

home healthcare. The basic home healthcare consists

at rendering health services to the aged or disabled

individuals in their home. In this case, different

persons and services are implied (medical and para-

medical professionals, nursing services, physical,

homemaker services, and social services). Also,

family members are involved in the healthcare

delivery. Concerning advanced home healthcare, it

may comprise the introduction of technological

solutions as e-mail consultations, clinical robots,

advanced sensor surveillance (for collecting vital

signs and physiological parameters), etc. In this

case, the patient may be less frequently visited by

involved actors than in regular basic home

healthcare (Arbaoui et al., 2012). Our work focuses

on advanced home healthcare and the use of

Information and Communication Technologies

(ICT), namely BPM technologies, to support and

improve it.

Unfortunately, home healthcare has to face

several challenges, such as funding limitations, large

geographic distances that make such resources often

more costly for rural patients, and issues of clinical

workforce distribution that impose access barriers to

these services. It is a general premise that ICT can

address these challenges and enhance home

healthcare services (Arbaoui et al., 2012). In fact,

advances in telecommunications have the potential

to support healthcare delivery and education. The

use of ICT can lead to a fundamental redesign of

home care processes based on the use and

integration of electronic communication at all levels

(Ellenbecke, 2008).

2.1 Basic Concepts

Home care providers deliver services at the patient's

own home. The goals of home healthcare services

are to help individuals to improve function and life

with greater independence; to promote the patient’s

optimal level of well-being; and to assist the patient

to remain at home, avoiding hospitalization or

admission to long-term care institutions (Demiris,

2010).

We may have recourse to home healthcare

according to different types of care (Zefouni, 2012

and FNEHAD, 2009):

Occasional care, especially in case of unstable

state of disease. Technical and complex care for

a predefined period (e.g. chemotherapy or

antibiotics);

Care rehabilitation at home, especially following

the acute phase of a neurological or heart

disease, or orthopedic treatment or early return

after childbirth;

Palliative care, especially intended to support

long term diseases;

Home healthcare goals stem mainly from the degree

of sector development in the government. Based on

the reports of (Lasbordes, 2010 and FNEHAD,

2009), the main goals of home healthcare are:

Ensure the safety of people dependent at home;

Ensure care quality, accessibility and

coordination.

Keeping patients in their homes areas. This is in

order to preserve the autonomy of the individual

and to avoid the breakdown of social ties;

Ensure the continuity of care, including keeping

the records of care and interventions in person

care at home;

Minimize the cost of care at home.

A Real-World Case Scenario in Business Process Modelling for Home Healthcare Processes

167

2.2 Current State Worldwide and in

Tunisia

Home healthcare structures have attracted a great

interest in the United States, Canada, Scandinavian

countries and the United Kingdom. Certainly, the

approaches differ from one country to another

(Polton, 2003), or within the same country (Abelson,

2004), but all seem to find a promising and

interesting field to be developed.

Some countries have resorted to these new home

healthcare support modes in order to free up hospital

beds. Others aim to control hospital costs. The

improvement of life quality of the patient was not a

primary objective for the countries studied by

(Raffy-Pihan, 1994).

According to a study by (Chevreul et al., 2004),

the French home healthcare system is closer to the

Australian one. This is from the point of view of

partial or total substitution of the offer acute care

hospitalizations in short-stay service. In the UK, the

system is closer to the Canadian’s, with oriented

continuous care for maintain or return to home of the

chronically ill or elderly patients. In Table I, we

present country examples home healthcare structures

studied by (Chevreul et al., 2004) and we added

Tunisia to this table, regarding the same factors

analyzed, namely the main reasons for recourse to

home healthcare and the nature of delivered care:

Table 1: Examples of worldwide structures (Chevreul et

al., 2004).

Countries

Main reasons for recourse

to home healthcare

Nature of delivered care

United

Kingdom

The overcrowding of care

beds at hospital due to not

justified clinically

accommodation and to

deficiencies in ambulatory

care.

Basic care, continuous,

for maintain / return to

home chronically ill or

elderly patients.

Canada

Compression of hospital

beds.

Basic care, long term

care substituting for

institutional care and

acute hospital care.

Australia

Inadequate traditional

hospital services

Highly technical care

France

The overcrowding of beds

at traditional hospital

Highly technical care,

acute or episodic care,

continuous care, follow-

up and rehabilitation

care

Tunisia

No supported home

healthcare in the public

sector.

Basic care, continuous

care for maintain / return

to home chronically ill or

elderly patients.

2.2.1 Description of the State of the Art in

Other Countries

Based on two experiences in Tunisia and Portugal

and some literature studies on related field (Raffy-

Pihan, 1994, Chevreul et al., 2004, Wendt, 2004 and

HAS, 2009), we present a description of home

healthcare in some countries. In fact, hospitals are

just one component in the overall organization of a

care system which includes primary care, accessible

during a first contact for unselected health problems,

and responsible for ensuring the continuity of care.

The responsibility of primary care falls mostly at the

local level (region, municipality or department).

While the general doctor is considered as the

entry point to focus on primary care, the direct

access to a specialist in primary care settings is

possible directly in Germany, Austria, Belgium,

France, and Switzerland. In these countries, the

number of specialists practicing in the primary care

setting is important. In several countries (UK,

Sweden, Portugal, Finland and Greece), primary

care is provided by multidisciplinary health centers.

In Sweden and the United Kingdom, the first contact

with a health professional is often performed by a

nurse. Finland has beds in its care center, making it

truly an intermediary structure between outpatient

care and hospitalization. In order to limit recourse to

general hospitals, most countries recommend the

primary care structure as the entry level of care,

either in a partial (Germany, Austria, Portugal,

Switzerland, France, Belgium, Finland, Spain) or

total manner (Denmark, Great Britain, Italy,

Norway, Netherlands).

To ensure hospital care, European countries rely

on three types of structures: public hospitals, non-

profit private hospitals and for-profit private

hospitals. Only a few countries rely almost all of

their hospital services in public hospitals (Denmark,

Finland, Norway, Sweden) or a majority of private

structures typically nonprofit (Belgium,

Netherlands). Most rely on both the public sector

and large private sector. The structures are often

small, and the number of beds is generally more

important in the public sector than in the private

sector. Moreover, private structures are, in most EU

countries, mostly non-profit hospitals (except

Austria and France).

In some countries (particularly Germany), a part

of the private institutions is providing care only to

some selected patients. We may identify three

groups of countries: those who had a lot of

equipment of any kind (Finland, Switzerland,

Austria, and Belgium), those who were poorly

HEALTHINF 2016 - 9th International Conference on Health Informatics

168

equipped (UK, Spain), and those that were heavily

equipped in some areas but weak in others (France,

Germany).

The responsibility of primary care falls mostly at

the local level (region, municipality or department).

This is the case for Denmark, Spain, Finland,

Greece, Great Britain, Ireland, Italy, Norway,

Portugal and Sweden. In countries with social

insurance systems (Germany, Austria, Belgium,

France and Switzerland), the insurance of credit

unions are responsible for supporting costs. While

the general doctor is considered as the entry point to

focus on primary care, the direct access to a

specialist in primary care settings is possible directly

in Germany, Austria, Belgium, France, and

Switzerland. In these countries, the number of

specialists practicing in the primary care setting is

important (48.5% in Germany, 50% in Austria).

In many countries, primary care is provided by

health centers. In this context, the access to a

specialist in primary care is sometimes possible,

particularly for obstetrics and gynecology, minor

surgery and psychiatry (Spain, Finland, Greece,

Portugal and Sweden). However for other

specialties, access to a specialist when needed is

done almost exclusively at general hospitals.

Registration with a doctor or health center, for a

time period and with limited choice, is the most

common model (Denmark, Spain, Great Britain,

Ireland, Italy, Norway, Netherlands, Portugal, and

Sweden). In other countries and most recently,

registration is encouraged by a financial incentive

mechanism (Germany and France). The status of

medical doctors is mostly liberal, but in health

centers, medical doctors are sometimes hired

employees (Finland, Portugal and Sweden).

Home healthcare includes home help

(housekeeping, cooking) and nursing. Home help is

not included in health care, but is considered part of

social services. However, nursing is part of health

care. They include rehabilitation care, support,

health promotion and technical nursing care for sick

people at home. Such care is provided in very

different ways from one country to another. They

vary depending on the chosen organizational model.

In some countries the nursing at home have long

been highly developed (Belgium, Denmark, Finland,

Ireland, Netherlands and United Kingdom), while in

others they are still developing (Austria, Greece,

Italy, Luxembourg, Portugal and Spain).

3 BPM FOR HOME

HEALTHCARE

Some research works highlight the importance of the

organizational aspects in the success of an ICT-

home healthcare project (Arbaoui et al., 2012).

Other works on home healthcare (Koch, 2004) have

dealt more with developing technical-based

solutions for home monitoring or home

telemedicine, leaving process aspects questions

unanswered (Arbaoui et al., 2012). Indeed, some

observations (Hamek et al., 2005) show that the

requirements of the home healthcare actors (nurses,

physicians, home healthcare organizations,

caregivers and patient’s family members) are more

oriented towards the improvement of the

organization and management of the home

healthcare system over a more intensive use of home

telemedicine (Arbaoui et al., 2012).

BPM represents a valuable asset in the healthcare

domain (Stefanelli, 2004), given the

competitiveness, rapid advancement and especially

the expansion of communication techniques and new

technologies in all research areas, as well as the

effectiveness of BPM tools to automate and better

manage business processes of organizations. It relies

on process models to identify, review, validate,

represent and communicate process knowledge

(Kunzle, 2011 and Müller, 2011).

Regarding several success stories on the uptake

of BPMS in industry and the emergent process-

orientation of enterprises, BPM technologies have

not had a widespread adoption in the healthcare

domain (Reichert, 2011 and Stefanelli, 2004). A

main reason for this has been the rigidity enforced

by the first generation of workflow management

systems, which inhibits the ability of a hospital to

respond to process changes and exceptional

situations in an agile way (Dadam, 2000). Process-

aware hospital information systems must be able to

cope with exceptions, uncertainty, and evolving

processes (Reichert, 2011). In this context, BPM

represents a response to design, manage, automate

and evaluate care processes. Another work of

Arbaoui et al. (2012) adopts a process based

approach to tackle home healthcare domain in order

to highlight the importance of organizational aspects

in the success of an ICT-home healthcare project.

They consider that a home healthcare may comprise

three sub-processes: 1) Organizational; 2)

Organizational care and 3) Care sub-processes. In

our work, we adopt a BPMN-based modeling

approach to organize home healthcare processes and

tackle associated challenges. Also, we adopt the

A Real-World Case Scenario in Business Process Modelling for Home Healthcare Processes

169

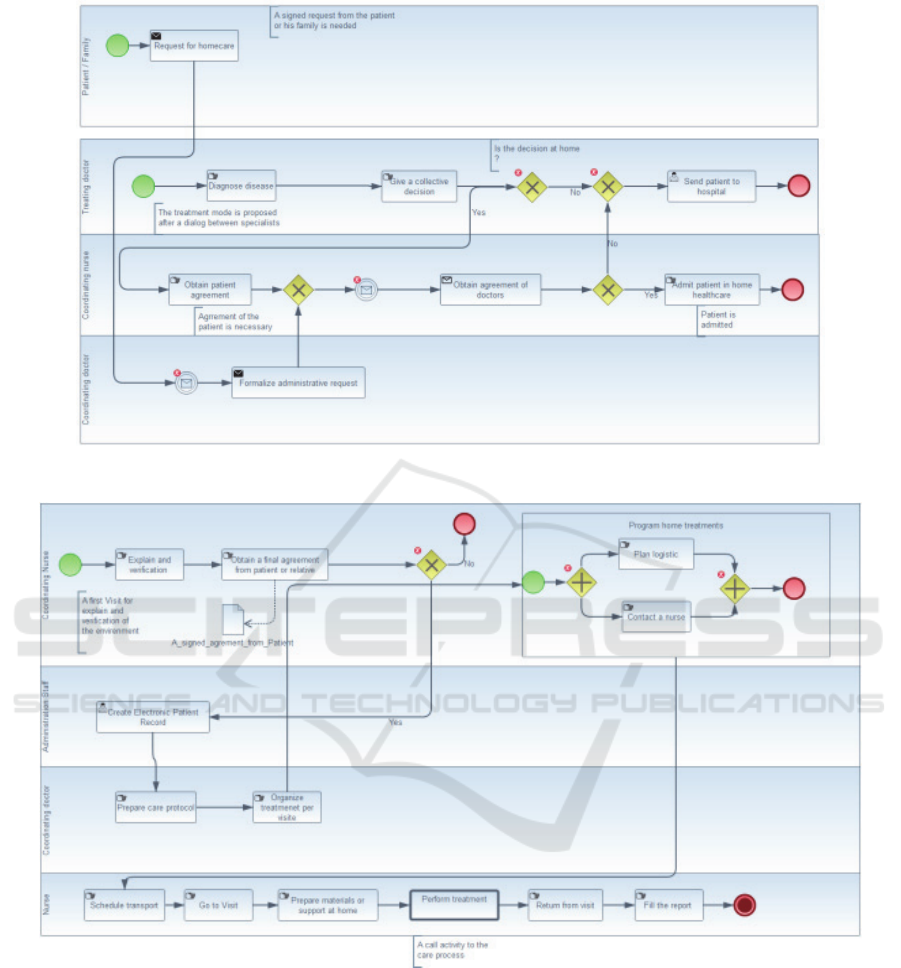

Figure 1: Organizational process model according to BPMN 2.0 Standard.

Figure 2: Organizational care process model according to BPMN 2.0 Standard.

division depicted by (Arbaoui et al., 2012).

4 HOME HEALTHCARE

PROCESSES: A CASE STUDY

IN TUNISIA

In this section, and following our interviews with the

involved actors (2 doctors, 3 nurses &

administration staff), we describe how home

healthcare is realized in Tunisia, who are the actors,

which are the different tasks and how we can design

all this information in a process model. We also

identify particular problems of home healthcare

processes concerning roles and task assignments

observed during real-world care process execution in

a home medical environment.

HEALTHINF 2016 - 9th International Conference on Health Informatics

170

4.1 Collecting Home Healthcare

Information

To study home healthcare processes, we led a field

research in which we interviewed actors with

different roles in the patient homecare (mainly nurse

coordinators, health aides and medical doctors). We

also followed the professionals in their daily work.

These observations have given us an overview on

the home healthcare management.

4.2 Proposed Models

The overall home healthcare process is divided into

three sub-processes, namely: 1) patient admission; 2)

organizational care; and 3) patient care.

4.2.1 Patient Admission Sub-process

This sub-process represents the result from

multidisciplinary consultation carried out between

different specialists. Once accepted to the home

healthcare mode, it will only be possible to involve

the treating doctor, the patient and her/his family.

The later should give an initial agreement with a

favorable opinion for the financial burden estimate.

Fig. 1 presents the organizational process model

according to the BPMN 2.0 standard. In fact, when

the disease is detected for a patient after diagnosis,

treatment and mode of treatment are proposed after a

dialog between different specialists. If the patient is

not accepted for home healthcare, s/he will be

treated in institutions or in traditional

hospitalization. This assumption of home care

management will be proposed to the patient under

her/his agreement. As shown in Fig. 1, the written

request of care is sent to the home healthcare

structure accompanied with details of treatment for

the patient. This request is then regulated by a doctor

and a nurse coordinator according to geographic,

medical, social and environmental criteria. In reality,

very few requests end up with a refuse (Bricon-souf

et al., 2005). Once the request is accepted, the type

of support of home healthcare is defined for patient,

which means the end of the admission sub-process.

4.2.2 Organizational Care Sub-process

Once the patient is admitted, a home visit is made by

the nurse coordinator of the establishment. S/he aims

to explain the full list of support programs for the

patient and to identify her/his needs. Then, the

patient may decide to be treated at home or to stay in

the hospital. If s/he goes for home healthcare,

hospitalization at home is definitely confirmed and

the record of patient will be created for a fixed

period.

As shown in Fig. 2, the patient's final

confirmation leads to a programming of home

treatments respecting the sequence of predefined

care prescriber and written by her/his treating

doctor. It is insured by the nurse coordinator of

home healthcare establishment. The next step of the

organization is to inform the planning of care for

logistics, nurses and treating doctor. Once the actors

defined, the nurse coordinator has the mission to

explain the care management and dates at which the

patient will need their intervention.

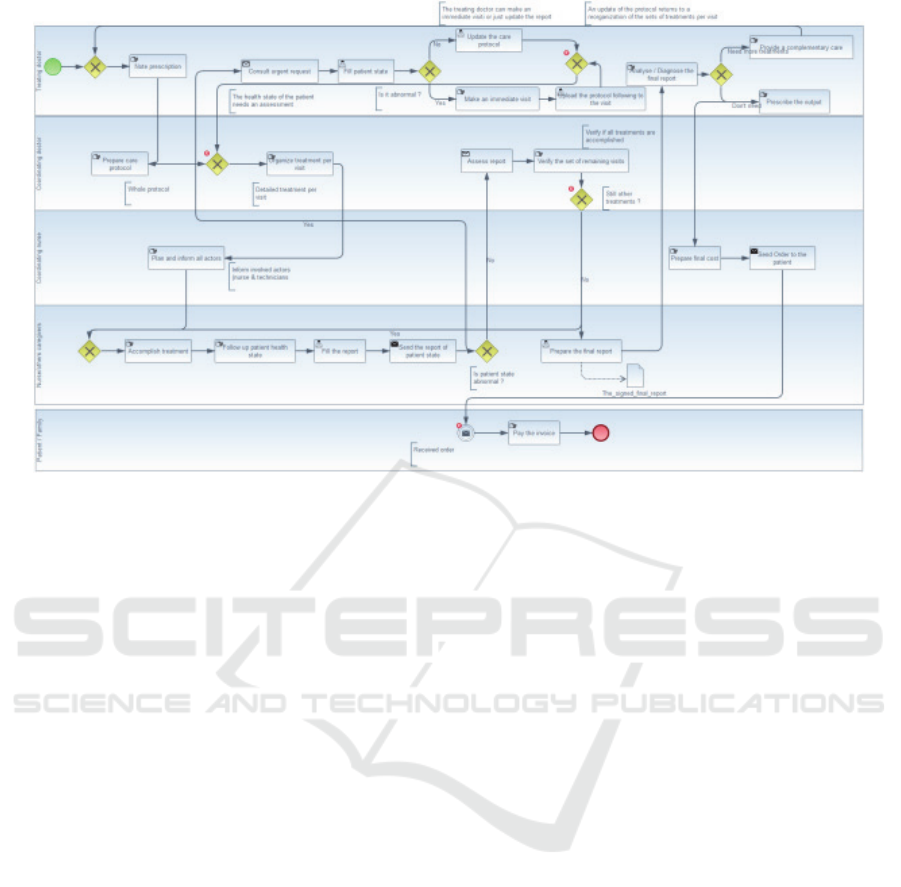

4.2.3 Patient Care Sub-process

The care sub-process is the core of home healthcare.

It is here where the various internal and external

actors are involved around the patient to deliver care

or services. This sub-process depends on the nature

of the diagnosis. At this step, there will be the

execution of care by appropriate actors and the

immediate reporting of related information as

follows:

Team providing care coordinating doctor of

home healthcare structure treating doctor

According to the patient’s diagnosis, the set of

involved actors becomes revealed (e.g., nurses,

physicians or other caregivers). In our care process

model, we present a lane for a coordinating nurse

which will notify all the needed actor(s) to be in

charge of care execution at home. This process

begins with a prescription from a treating doctor.

After that, the coordinating doctor will prepare the

care protocol in order to be organized per visit.

Then, the coordinating nurse informs all involved

actors. After treatment per visit is done, the nurse

must follow-up the patient’s health state and prepare

a report. If the state is abnormal, the information

should pass to a treating doctor urgently. At this step

and according to received data from our

interviewees, the treating doctor makes a decision

either on an update of the care protocol or by

making a visit before updating. This update may

result into a new instance of the “Organize treatment

per visit” task.

On the other hand, if patient health state is

normal a conditional gateway takes place in order to

control if current treatment is the last one or still

other visits with other treatments should follow. So,

if there is another visit, the process will return to the

“Accomplishment of treatment(s)” task by the nurse.

Otherwise, i.e. no other treatment, the nurse must

A Real-World Case Scenario in Business Process Modelling for Home Healthcare Processes

171

Figure 3: Care process model according to BPMN 2.0 Standard.

prepare a final report. It will be analyzed by treating

doctor in order to make a decision about the patient:

providing a complementary care or prescribing the

output from hospitalization at home. This leads to

preparing a final cost assessment. Finally, the pay of

the invoice ends the process.

4.3 Identified Problems

In this case study in Tunisia, we have identified

some related issues from the interviews performed.

For instance, information about the collaboration

between actors is often lost, e.g. when the patient’s

health state is critical an immediate intervention

from the treating doctor at home is forced. This is

due to the lack of a communication system between

nurse and treating doctor. Currently, the only

communication medium is the mobile. Also, the full

process is mainly based on manual tasks e.g. treating

doctor must go to the patient’s home for frequent

visits. This is due to the lack of ICT-based home

healthcare (electronic records, telemedicine).

Another related problem is the lack of support from

health insurances and lack of home healthcare

related culture. In addition, care coordination is a

challenge. Health professionals need to coordinate

care for a better and fast intervention. Another issue

is that organizational processes (and patient-care

processes in particular), change over time. This may

be due to unpredicted (home healthcare) situations.

4.4 BPMN Coverage for Home

Healthcare Processes

Proposed models describe the care tasks for the

Tunisian home healthcare processes case. Also,

while refining these process models with the

involved home healthcare actors, they do not have

difficulties in identifying the process activities and

actors.

Modeling complex processes, such as those of

home healthcare, has always been a continuous

challenge. As an important factor in modeling,

models must be easily understood by their target

users. Also, an appropriate level of detail aims to

fulfill their development purposes. In addition,

healthcare systems have specific modeling

requirements such as collaboration,

understandability and flexibility.

Following interviews with involved actors, we

assume that our proposed models follow a more

imperative (prescriptive) modelling approach. This

can be observed in the first and second models. On

the other hand, regarding the third care clinical

process, it requires a more declarative modelling

approach, since there may be some tasks that are

executed in a different order from instance to

instance, and unforeseen exceptions may happen.

HEALTHINF 2016 - 9th International Conference on Health Informatics

172

5 NEXT RESEARCH STEPS

In further work, we plan to optimize these models by

analyzing which tasks can be automated or

rationalized. Then we intent to implement these

models of home healthcare processes within the

jBPM BPMS (Cumberlidge, 2007). Then, and after

registering execution instances, we will perform an

analysis in order to identify bottlenecks and

challenges reported from users of the implemented

BPMS. After that, we expect to propose an

improved business process, and again perform the

BPM cycle.

Parallel to these steps, we are aiming to perform

additional interviews on home healthcare processes,

in order to assess the degree of similarity between

business processes for home healthcare in other

countries. From here, we plan to propose a group of

home healthcare processes that can serve as template

and guidelines to help normalize home healthcare in

more than one organization/country.

6 CONCLUSIONS

In this work we have documented process models

which reflect real-world scenario from a private

clinic which provides home healthcare in Tunisia.

Our proposed process models describe all care tasks

in a Tunisian private clinic. We could also observe

that, for these home healthcare processes, the BPMN

language is mostly suited for the first two

organizational and organizational-care processes,

which are more static and rigid. Care (clinical)

processes revealed to be unstable, requiring a

different modeling approach. That is why we agreed

with our interviewed personnel on a more generic

care process, not only because it varies on the

diagnosis, but also because real cases are not too

much predictable.

REFERENCES

Abelson, J., Gold, S. T., Woodward, C., O’Connor, D., &

Hutchison, B., 2004, Managing under managed

community care: the experiences of clients, providers

and managers in Ontario’s competitive home care

sector. Health Policy, 68(3), 359-372.

Arbaoui, S., Cislo, N., & Smith-Guerin, N., 2012. Home

healthcare process: Challenges and open issues. arXiv

preprint arXiv:1206.5430.

Bachouch, R. B., 2010. Pilotage opérationnel des

structures d'hospitalisation à domicile (Doctoral

dissertation, INSA de Lyon).

Bricon-Souf, N., Anceaux, F., Bennani, N., Dufresne, E.,

& Watbled, L., 2005. A distributed coordination

platform for home care: analysis, framework and

prototype. International Journal of Medical

Informatics, 74(10), 809-825.

CHEVREUL, K., COM-RUELLE, L., MIDY, F., &

PARIS, V., 2004. Le développement des services de

soins hospitaliers à domicile: éclairage des expériences

australienne, britannique et canadienne. Questions

d'économie de la santé, (91), 1-8.

Cumberlidge, M., 2007. Business Process Management

with JBoss jBPM. Packt Publishing Ltd.

Dadam, P., Reichert, M., & Kuhn, K., 2000. Clinical

workflows the killer application for process-oriented

information systems? (pp. 36-59). Springer London.

Demiris, G., 2010. Information technology and systems in

home health care. In The role of human factors in

home health care: Workshop summary (pp. 173-200).

Ellenbecker, C. H., Samia, L., Cushman, M. J., & Alster,

K., 2008. Patient safety and quality in home health

care. Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based

Handbook for Nurses. Rockville (MD).

FNEHAD, 2009, Fédération Nationale des Etablissements

d’Hospitalisation A Domicile, Institutional Report.

Livre Blanc des systèmes d’information en

hospitalisation à domicile (Retreived from

www.fnehad.fr).

Hamek, S., Anceaux, F., Pelayo, S., Beuscart-Zéphir, M.

C., & Rogalski, J., 2005. Cooperation in healthcare-

theoretical and methodological issues: a study of two

situations: hospital and home care. In Proc. of the

2005 annual conference on European association of

cognitive ergonomics (pp. 233-240). University of

Athens.

HAS, 2009. Le recours à l’hôpital en Europe.

Ilahi, L., & Ghannouchi, S. A., 2013. Improving

Telemedicine Processes Via BPM. Procedia

Technology, (9), 1209-1216.

Ilahi, L., Ghannouchi, S. A., & Martinho, R., 2014.

Healthcare information systems promotion: from an

improved management of telemedicine processes to

home healthcare processes. In Proc. of the 2nd Int.

Conf. on Technological Ecosystems for Enhancing

Multiculturality (pp. 333-338). ACM.

Koch, S., 2004. ICT-based Home Healthcare:-Research

State of the Art.

Kun, L. G., 2001. Telehealth and the global health

network in the 21 st century. From homecare to public

health informatics. Computer methods and programs

in biomedicine, 64(3), 155-167.

Künzle, V., & Reichert, M., 2011. PHILharmonicFlows:

towards a framework for objectaware process

management. Journal of Software Maintenance and

Evolution: Research and Practice, 23(4), 205-244.

Lasbordes, P., 2010. La télésanté, un nouvel atout au

service de notre bien-être. Soins la revue de reference

infirmiere, (750), 26.

Müller, R., & Rogge-Solti, A., 2011. BPMN for healthcare

processes. In Proceedings of the 3rd Central-

A Real-World Case Scenario in Business Process Modelling for Home Healthcare Processes

173

European Workshop on Services and their

Composition (ZEUS 2011), Karlsruhe, Germany.

Polton, D., 2003. Décentralisation des systèmes de santé:

Quelques réflexions à partir d'expériences

étrangères. Questions d'économie de la santé, (72), 1-8.

Raffy-Pihan, N., 1994. L’Hospitalisation à Domicile: un

tour d’horizon en Europe, aux Etats-Unis et au

Canada, rapport n 1045. IRDES (ex. CREDES).

Redjem, R., 2013. Aide à la décision pour la planification

des activités et des ressources humaines en

hospitalisation à domicile (Doctoral dissertation,

Université Jean Monnet-Saint-Etienne).

Reichert, M., 2011. What BPM technology can do for

healthcare process support. In Artificial Intelligence in

Medicine (pp. 2-13). Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

Stefanelli, M., 2004. Knowledge and process management

in health care organizations. Methods Inf Med, 43(5).

Wendt, C., & Thompson, T., 2004. Social austerity versus

structural reform in European health systems: a four-

country comparison of health reforms. International

Journal of Health Services, 34(3), 415-433.

Woodward, C. A., Abelson, J., & Hutchison, B. G.,

2001. My home is not my home anymore: improving

continuity of care in homecare. Canadian Health

Services Research Foundation Fondation canadienne

de la recherche sur les Services de santé.

Zefouni, S., 2012. Aide à la conception de workflows

personnalisés: application à la prise en charge à

domicile (Doctoral dissertation, Université de

Toulouse, Université Toulouse III-Paul Sabatier).

HEALTHINF 2016 - 9th International Conference on Health Informatics

174