WHAT IS THE RIGHT SERVICE? A MULTI-CRITERIA

DECISION MODEL BASED ON ‘STEP’

Tobias Mettler

1

and Markus Eurich

2,3

1

SAP Research St.Gallen, Blumenbergplatz 9, 9000 St. Gallen, Switzerland

2

SAP Research Zürich, Kreuzplatz 20, 8008 Zürich, Switzerland

3

Department of Management, Technology and Economics, ETH Zürich, Scheuchzerstrasse 7, 8092 Zürich, Switzerland

Keywords: Analytic hierarchy process, Decision model, Information intensive services, IT-business value, Service

selection, STEP, Web services.

Abstract: Together with the diffusion of the Internet both private and legal persons have designed a wide variety of

information intensive services. At the same time, concepts and methods have been developed to facilitate

the description, discovery, composition, and consumption of these services. However, the selection of the

right service still represents a major problem for consumers, since policy-, reputation- or trust-based

selection techniques often do not lead to the desired results. In this paper a multi-dimensional service

selection model - including social, technological, economic, and political considerations - is presented that

can help service consumers in this sketchy and complex task.

1 INTRODUCTION

Providers of information intensive services still face

many problems in regard to the collaboration with

globally distributed business partners. High demands

on service accessibility and reliability, lack of

widely accepted standards for service definition and

orchestration, complicated pricing models as well as

language problems are some of the reasons why the

global provisioning of services has not yet become

commonplace (Schroth, 2007).

Different connotations and meanings for the term

‘service’ exist in distinct disciplines such as

information systems, business administration or

computer science (Baida, Gordijn, and Omelayenko,

2004). In this paper we use the term service as “the

application of specialized competences (knowledge

and skills) through deeds, processes, and

performances for the benefit of another entity or the

entity itself” (Vargo and Lusch, 2004). By that

definition a wide range of possible manifestations of

services are opened, for example: tangible (products)

and intangible services; automated, IT-reliant and

non-automated services; customized, semi-

customized and non-customized services; personal

and impersonal services; repetitive and non-

repetitive services; and services with varying

degrees of self-service responsibilities (Alter, 2008).

With respect to information intensive services

the Organization for the Advancement of Structured

Information Standards has defined the Unified

Service Description Language (USDL) in order to

help service providers describe technical and

business-related properties. In contrast to the former

Web Service Description Language (WSDL), which

focused on a pure technical characterization of the

service concept, USDL includes information about

the participants, interaction between these parties, a

delineation of the service level and pricing and legal

as well as functional aspects. These service

descriptions can then be published in public or

closed community repositories, service registries, or

the provider’s website in order to enable consumers

to discover the offered services. According to Alter

(2007) there is still the need for negotiated

commitments, under which the service may be

delivered many times. Flexibility, quality, and

thoroughness of negotiated mutual commitments is

thus a key determinant of whether long term service

agreements will fully meet the consumers’ needs

(Cullen et al., 2005).

Consumers on their part, may they be

individuals, groups or organizations, thus have to

define (or at least have an idea of) what their exact

business needs are. This may be driven from an

inside-out perspective, e.g. derived from the

81

Mettler T. and Eurich M..

WHAT IS THE RIGHT SERVICE? A MULTI-CRITERIA DECISION MODEL BASED ON ‘STEP’.

DOI: 10.5220/0003452400810090

In Proceedings of the International Conference on e-Business (ICE-B-2011), pages 81-90

ISBN: 978-989-8425-70-6

Copyright

c

2011 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

corporate strategy, or from an outside-in perspective,

e.g. induced by market trends. Once the

requirements are clear, a consumer has to find

services which may satisfy the identified needs. In

doing so, a consumer may refer to search engines

and software agents, rely on professional service

brokers or word of mouth. However, the key

challenge for consumers is not discovery, but

selection. In accordance with Sreenath and Singh

(2004) the key issue is that in most instances, service

descriptions are given from the perspective of

providers and do not necessarily include information

relevant for the consumers. The selection of a

particular service may not only be motivated by the

best technical features or the lowest price, but by

multiple criteria such as cultural fit or ethical and

legal aspects (Krishna et al., 2004). Nevertheless,

matchmaking mechanisms or algorithms for

selecting information intensive services (e.g.

Maximilien and Singh, 2004; Yu et al, 2007) still

mainly rely on technology-oriented criteria.

Due to the increase of the number of available

services offered on vendor websites, service

registries, or electronic marketplaces, we see a

necessity of having an informed approach for service

selection that also takes business, cultural, and legal

considerations into account. It is the aim of this

paper to address the problem of service selection in a

holistic manner by defining a multi-dimensional

decision model. To this end, the paper is organized

as follows: after this introduction, we first provide

an examination of the related work on general

service selection techniques and discuss their

suitability with respect to information intensive

services. In the section that follows, we describe

potential criteria for service selection for each of the

mentioned dimensions. Subsequently, the decision-

making procedure is presented and illustrated by

means of a comprehensive case study. Finally, we

present some concluding remarks and offer some

suggestions for future research.

2 RELATED WORK

There is a wide range of research conducted in the

field of service discovery and selection. Comparing

and categorizing these works is not an easy job as

one service is not like another and the measurement,

especially of the quality of a service, is not trivial

either.

In order to establish a semblance of order in our

literature review, we focused on service selection

and on information intensive services. First, we

defined ‘service discovery’ as the process of finding

and retrieving services that fulfill the wanted

functionality, whereas ‘service selection’ refers to

the process of choosing one service among several

with adequate functionality on the basis of different

criteria. Over the further course of this paper we

focus on the latter. Second, services vary in their

complexity. Kugyt (2005) places services on a

spectrum between ‘professional services’ on the one

extreme and ‘mass services’ on the other.

Professional services are characterized by a formal

relationship, the importance of the service for the

overall welfare of the customer, a high

customization, the importance of a critical judgment,

and a centering on people. Mass services are on the

contrary: in other words, there is no formal

relationship, no importance of the service for the

overall welfare of the customer, no customization,

no importance of a critical judgment, and the

services are equipment-based (cf. Collier and Meyer,

2000, Ettenson and Turner, 1997). In this article, we

will concentrate more on professional services,

which we call ‘complex services’, and which we

basically understand as information intensive

services. We refer to simple services or commodities

as mass services. With this background, several

techniques qualify for a more detailed appraisal,

including heuristics, policy-based approaches,

reputation- and trust-based selection techniques,

multi-criteria decision analysis, UDDI-extensions,

and ontology-based preference modeling

approaches.

An optimal service can only be selected if an

optimal service actually exists as well as a strategy

to find it (Gigerenzer, 2007, p. 86). If this is not the

case, heuristics can help in choosing services that

are good enough. Gigerenzer (2004) provides an

overview of fast and frugal heuristics, which stop the

search immediately if a factor allows it. The factors

need to be retrieved in order of their importance.

This has the advantage that a fast and frugal tree

only has n + 1 leaves whereas a full tree has 2

n

leaves, which can make a full tree computationally

intractable. Heuristic approaches for service

selection are described, for instance, in Menascé et

al. (2008 and 2010). Heuristics are useful for service

selection problems, where no optimal solution exists

or where finding the solution is too expensive or

even computationally intractable. They are less

suitable for multi-criteria decisions and may have

some weaknesses if the selection decision is made

by a human. One weak spot is the base-rate fallacy,

which is the finding that “people are relatively

insensitive to consensus information presented in the

ICE-B 2011 - International Conference on e-Business

82

Table 1: Techniques for complex service selection.

Service Selection

Technique

Pro Contra

Heuristics

Fast / cheap / often good enough / suitable for

simple service selection

Unsuitable for multi-criteria or multi-person decisions

Policy-based Considers preferences and limitations of the requestor

Translation of policies (to make them machine readable)

is complex and time-consuming

Reputation-/ trust-based

Decision can be based on own and others’

experiences

Long time to build up reputation- and trust community /

potential of manipulation of evaluations

Multi-criteria decision

analysis

Accommodation of multiple criteria, facilitation of

participation, simple and intuitive character

Lengthy duration of the process / boost of effort with

increasing number of criteria

UDDI-extensions

Monitoring the performance, safety, and price of

services

Limited focus: overemphasize on technical aspects /

quality information and service data are separated

Ontology-based

preference modeling

Automatically interpretable / ability to automatically

derive new relationships between concepts of your

ontology

Difficulties in mapping ontologies / big effort to define an

ontology

form of numerical base rates” (Brehm et al., 2005, p.

108).

Similar to heuristics are policy-driven

approaches for service selection, which are based on

the specification of non-functional requirements

coded in a Quality of Service (QoS) policy model

(Yu and Reiff-Marganiec, 2008). The QoS policy

model contains the service requestor’s policies like

preferences and restrictions. Policy-based

approaches are outlined, for instance in Janicke and

Solanki (2007) or Liu et al. (2004). Just like for

heuristics one disadvantage is the difficulty in

translating non-functional criteria to allow

computation. The formulization of non-functional

criteria is time-consuming and tricky, as the criteria

have to be formulated as numbers or in another

format. In principle, policy-based approaches could

be applied for basic service selection as well as for a

complex one.

Policy-based approaches – like most approaches

for services selection – select the service on the basis

of information provided by the service provider and

try to match this information with the service

requestor’s selection criteria. Yet, a major difference

of reputation- and trust-based selection techniques

is the introduction of a trusted third party.

Reputation- and trust-based selection approaches are

genuinely meant for service selection, while most

other approaches can also be used – or are indeed

even designed – for service discovery. Some

literature is summarized in Yu and Reiff-Marganiec

(2008), of which Wang and Vassileva (2007) and

Galizia (2007) can be recommended for further

reading. The advantages of these approaches are that

they can be used for any arbitrarily complex service

and that non-functional requirements like legal

issues, reliability, or availability parameters can also

be incorporated into the selection process. On the

downside, there is no real deployment of this

approach in the real world yet due its high

complexity (one service is not like another) and the

enormous amount of time needed to establish a

“trust and reputation”-community. Another

drawback is the potential of manipulation of

evaluations.

Another kind of service selection is multi-criteria

decision analysis, which qualifies for numerous and

possibly conflicting evaluations. Multi-criteria

decision analysis methods are particularly well

suited for complex service selection, for which

several criteria need to be judged. Multi-criteria

decision analysis methods include Analytic

Hierarchy Process (AHP) and its successor Analytic

Network Process (ANP), goal programming, and

weighted product or sum models. The AHP is, for

example, used for a QoS-based web service

selection in Wu and Chang (2007). It is also

applicable as a decision support model for managers

to understand the trade-offs between different

criteria by group properties and thus structuring the

decision (e.g. Handfield, et al., 2002). Advantages of

the AHP include the support of both subjective and

objective criteria, the accommodation of multiple

criteria, the facilitation of participation, and its

simple and intuitive character. A disadvantage might

be the lengthy duration of the process.

Universal Description, Discovery and Integration

(UDDI) is a directory service that provides a

mechanism to register and locate web services. The

UDDI repository basically consists of three

components: the white pages (similar to a phone

book, which gives information about the service

providers supplying the service), the yellow pages

(similar to the “Yellow Pages”, which provide a

classification of the services), and the green pages

(which are used to describe how to access a service

and which control the congruency between the

service provider’s offers and the requestor’s needs).

While standard UDDI can be used for service

discovery, UDDI-extensions aim at supporting

service selection. Seo et al. (2005), for example,

propose the introduction of a quality broker in the

WHAT IS THE RIGHT SERVICE? A MULTI-CRITERIA DECISION MODEL BASED ON 'STEP'

83

service-oriented architecture between the service

requestor and the UDDI repository. The quality

broker monitors the performance, safety, and price

of services, which are registered in the UDDI

repository. Yu and Reiff-Marganiec (2008) also

assess UDDI-based approaches for service selection

and come to the conclusion that there are two

disadvantages: (1) information about the quality and

service data are separated, and (2) there is no

extensible service quality model, i.e. the selections

are limited to few predefined criteria. Another

weakness of this approach is its limited focus: there

is an overemphasis on technical aspects while e.g.

legal aspects are neglected.

Other ways of service selection are ontology-

based preference modeling approaches. In computer

and information science, “an ontology refers to an

engineering artifact, constituted by a specific

vocabulary used to describe a certain reality, plus a

set of explicit assumptions regarding the intended

meaning of the vocabulary words” (Guarino, 1998).

Adopting this definition implies two important

premises: (a) the ontology is specified in form

(syntax) and content (semantics), and (b) the

ontology is appropriate to represent a consolidated

world-view of a delimited domain (pragmatics).

Consequently, for service selection, the selection

criteria of a service requestor are formalized with

semantic vocabulary and a domain structure for the

classification. For example, Sutterer et al. (2008)

describe user profiles including their preferences in

an ontology. García et al. (2010) define a preference

ontology for service selection and ranking. Yu and

Reiff-Marganiec (2008) model the service

requestor’s preferences and use this ontology model

as criteria for service selection. This approach makes

it possible to define weights for the preferences

either by the service requestor or by the system to

handle emergent behavior. An advantage of this

ontology-based preference modeling approaches is

that it is automatically interpretable by machines. A

bunch of advantages stem from the functions

reasoning, inference, and validation, which basically

means that you are able to automatically derive new

relationships between concepts of your ontology.

Still, major disadvantages are the difficulties in

mapping ontologies and the effort to define an

ontology and to keep it up to date.

As mentioned before, in our literature review we

focused on service selection for information

intensive and compared several selection techniques.

(Table 1). A good comparison of service selection

methods is also presented in (Yu and Reiff-

Marganiec, 2008) on the basis of seven requirements

for web service selection approaches, which are:

model for non-functional properties, hierarchical

properties, user preferences, evaluation of

preferences, dynamic aggregation, automation, and

scalability and accuracy.

As summarized in Table 1, all discussed service

selection techniques have advantages and

disadvantages. While heuristics might be the easiest

and most convenient method for simple service

selection, we consider multi-criteria decision

analysis - and in particular AHP – as a superior

technique for complex service selection. One major

drawback of AHP is its lengthy process. However,

once set-up, the process can be automated and

several software tools are available to support the

decision process. The application of AHP for service

selection is not new and has been adopted for many

different settings (e.g. selection of ERP vendor or

communications service provider, cf. Wei et al.,

2005). With this paper we want to extend the current

field of application and show how AHP generally

can be applied for decision-making in the complex

area of information intensive services.

3 CRITERIA FOR SELECTING

INFORMATION INTENSIVE

SERVICES

The selection of the right information on intensive

service involves the balancing of a series of multi-

dimensional and often interrelated aspects. The

STEP (Social, Technological, Economic, Political)

approach, also referred to as PEST (Peng and Nunes,

2007), STEEP (second ‘E’ stands for

‘Environmental’, Voros, 2001), or PESTLE (‘L’

stands for ‘Legal’, Warner, 2010), offers a proven,

integral framework for guiding a complex decision-

making process. A general assumption is that not

only directly assignable effects, such as the price or

defined service levels, but also external or indirect

circumstances, such as the image of the service

provider, or cultural fit with the company, are also

likely to influence organizational investment

decisions. To identify these influencing factors and

get a ‘satellite view’ for a holistic choice, the

decision-making process is based on four

dimensions: technological, social, economic, and

political. In order to identify the most relevant

decision criteria for selecting information intensive

services, our literature review adheres to this

classification and thus can be designated as

‘concept-centric’ (Webster and Watson, 2002).

ICE-B 2011 - International Conference on e-Business

84

3.1 Technological Dimension

The main focus of service selection is often more or

less limited to the technological dimension and a

great part of current service selection techniques

mainly uses QoS-metrics (e.g. Maximilien and

Singh, 2004; Tian, et al., 2003) as a basis for

decision-making. In particular under the label of

QoS, characteristics of technological usability as a

basis for service selection have been widely

discussed (e.g. Liu, et al., 2004; Zeng, et al., 2003).

Because QoS is defined and measured in different

ways, we do not want to rehash a discussion about

the subject, but rather focus on the three major

concepts of usability as defined by the International

Organization for Standardization (ISO-9241).

The first central concept to render usability is

efficiency, which is commonly referred to as the

level of resources consumed in performing a specific

task. In regard to information intensive services,

efficiency can be quantified by a service’s

processing time (throughput), response time

(latency), or capacity (guaranteed performance).

Effectiveness is the second fundamental concept

for quantifying the quality of a service. According to

Rengger et al. (1993), effectiveness is comprised of

two aspects, namely the number of tasks the user

completes and the quality of the goals the user

achieves (output). With respect to the quantity, the

scalability of a service is of major importance, since

it represents a service provider’s capability of

increasing his capacity and ability to process more

service consumer requests, operations, or

transactions in a given time interval (W3C Working

Goup, 2003). In regard to quality, criteria such as

robustness (the degree of quality provided even in

the presence of invalid, incomplete or conflicting

inputs), reliability (the ability to perform a service

under the stated conditions for a specified time

interval), integrity (consistency of information and

processing), and timeliness (actuality of information

and punctuality of provision) can be used as units of

measurement.

Finally, the service consumer’s subjective

satisfaction with using the technology is another

inherent concept for service selection. From a

technological point of view, satisfaction or perceived

usefulness of the rendered service is positively

influenced by its ease of use (Wixom and Todd,

2005). For example, this might be assessed by

inspecting a service’s integration possibilities (e.g.

integration into regular tasks), adaptability (e.g.

possibility to readjust service levels), or exception

handling.

3.2 Social Dimension

QoS-metrics are often restricted to characteristics of

technological usability (as described in the previous

sub-section) and do not consider social aspects for

service selection. No matter where information

intensive services are used – be it business-to-

business or business-to-consumer - concepts such as

trust (e.g. Billhardt, et al., 2007; Liu, 2005),

reputation (Ding, et al., 2008; Wang, et al., 2009)

and cultural fit (Javalgi and White, 2002) play an

important role in decision-making.

The concept of trust as basic principle for

establishing business relationships and social

phenomenon has been widely investigated in the

past years (e.g. McEvily, et al. 2003). According to

Castelfranchi and Faclone (1998), trust can be

gained by the service provider’s competence,

disposition, persistence, as well as the belief on his

dependence, cooperation willingness, and self-

confidence. Reference points for assessing the

trustworthiness of a service provider of an

information intensive service are, for instance, a

transaction history (Manchala, 2000), a sociability

index (Smoreda and Thomas, 2001) or a competency

index (Hu, 2010).

Another concept that is central from a social

perspective is reputation, which generally can be

defined as the “public’s opinion about the character

or standing (such as honesty, capability, reliability)

of an entity” (Wang and Vassileva, 2007). Like trust,

it is based on the long-term experiences that the

different service consumers have made when

collaborating with a particular service provider.

However, in contrast to trust, which can be allocated

on different levels (e.g. trust in the service itself,

trust in the service provider), reputation is merely

focused on a private or legal person and thus can be

independent from a service offer. In this sense, not

the quality of the service is in focus, but the quality

of the service provider. Useful means to ascertain

the reputation of a service provider could be a rating

history (Maximilien and Singh, 2004) or the

electronic word-of-mouth in online platforms

(Hennig-Thurau, et al., 2004).

Although several studies report a significant

interrelation between culture and user interaction

(e.g. Birukou, et al., 2007), the concept of cultural fit

is often neglected in service selection techniques.

Reasons for this are probably the difficulty in

capturing ‘culture’ in tangible terms as well as the

diversity of divergent understandings that are

attributed to this concept. In a broad sense, culture

can be conceived as a collective phenomenon that is

WHAT IS THE RIGHT SERVICE? A MULTI-CRITERIA DECISION MODEL BASED ON 'STEP'

85

manifested in several ways such as by common

symbols, heroes, rituals, values, and practices

(Hofstede and Hofstede, 2005). For instance, Forest

and Arhippainen (2005) discovered that there is a

considerable difference in the way how Finish and

French users interact with IT-based services.

Consequently, it can be assumed that cultural

differences play an important role when selecting a

particular service. In order to include it in the

decision-making process for selecting a service, it

must be narrowed down to concrete conceptions

such as for example linguistic affiliation (e.g. does

the service provider support all the different

languages that are spoken in the company),

professionalism (e.g. does the service provider

certify a certain capability level), philosophy (e.g.

does the service provider share the same values with

respect to specific subjects), or business conduct

(e.g. does the service provider apply the same or

similar standards to business transactions).

3.3 Economic Dimension

In QoS policy models, the price is often the only

economic criterion for service selection (e.g. Liu, et

al., 2004). However, especially in the context of

information intensive services, not only the costs,

but also the benefits of utilizing the service (instead

of accomplishing the required output on one’s own

or resigning) are important.

With respect to costs, a differentiation between

non-recurring costs, ongoing costs (the price

typically is a combination of both) as well as

switching costs is needed. Non-recurring costs are,

for instance, the purchase of a commercial software

license, payment of a registration or activation fee,

or one-time investment costs for infrastructure and

training in order to effectively using the service. On

the other hand, exemplary ongoing costs are

subscription fees, utility-based maintenance and

support costs, or user-based cost additions for using

special service characteristics. Finally, when

changing a service provider, switching costs must be

considered, too. According to Farrell and Klemperer

(2007), switching costs may be transactional (e.g.

returning of equipment), contractual (e.g. exit fees)

as well as search and learning costs (e.g. retraining

of employees). In addition, psychological,

emotional, and social costs may incur.

Considerable research is available on how to

assess the economic benefits of IT; however, it is

less common to specifically study them in relation to

information intensive services. Following Mirani

and Lederer (1998), advantages may occur on a

strategic (e.g. enhanced customer relations),

informational (e.g. improved decision-making), and

transactional dimension (e.g. money savings or

productivity increases).

3.4 Political Dimension

Although having an exceptional great impact on the

final decision, political considerations are often

neglected in current service selection techniques.

One reason for this is that a wide mix of issues must

be addressed, which usually makes it difficult to

replace human intervention through programmatic

means such as UDDI-extensions or QoS-algorithms.

Accordingly, different stakeholders might be

involved (Chatterjee and Webber, 2004). Among

other considerations, the concepts of dependability

and regulatory compliance play a major role.

Unlike the technological connotation of

dependability, which generally uses this term to

describe the trustworthiness of an IT-system based

on its availability, reliability, safety, integrity, or

maintainability (Avizienis, et al. 2004; Wang and

Vassileva, 2007), we rather associate the service

consumer’s subservience to a particular condition of

a service provider’s offer with it (commonly referred

to as lock-in). In the context of information intensive

services this might come to light when a service

provider’s market power is high enough to

circumvent the compatibility or interoperability of a

service by proprietary characteristics or to enforce

additional obligations. Not least, a service should be

also assessed whether it is capable to comply with

national and/or international regulations (e.g.

standard services directive) as well as with the own

needs for privacy protection.

4 DECISION-MAKING WITH

AHP AND STEP

The Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP) was

devised by Saaty (1980) and became one of the most

– or even the most – prevalent model for multi-

criteria decision-making. The AHP provides a

framework for solving multi-criteria decision

problems based on the relative importance of the

criteria assigned to each criterion in achieving the

overall goal (e.g. Handfield, et al., 2002). The AHP

technique is particularly suitable for multi-criteria

and also multi-person decision making, in which

subjective managerial opinions are present. The

advantages of AHP over the other methods (cf.

ICE-B 2011 - International Conference on e-Business

86

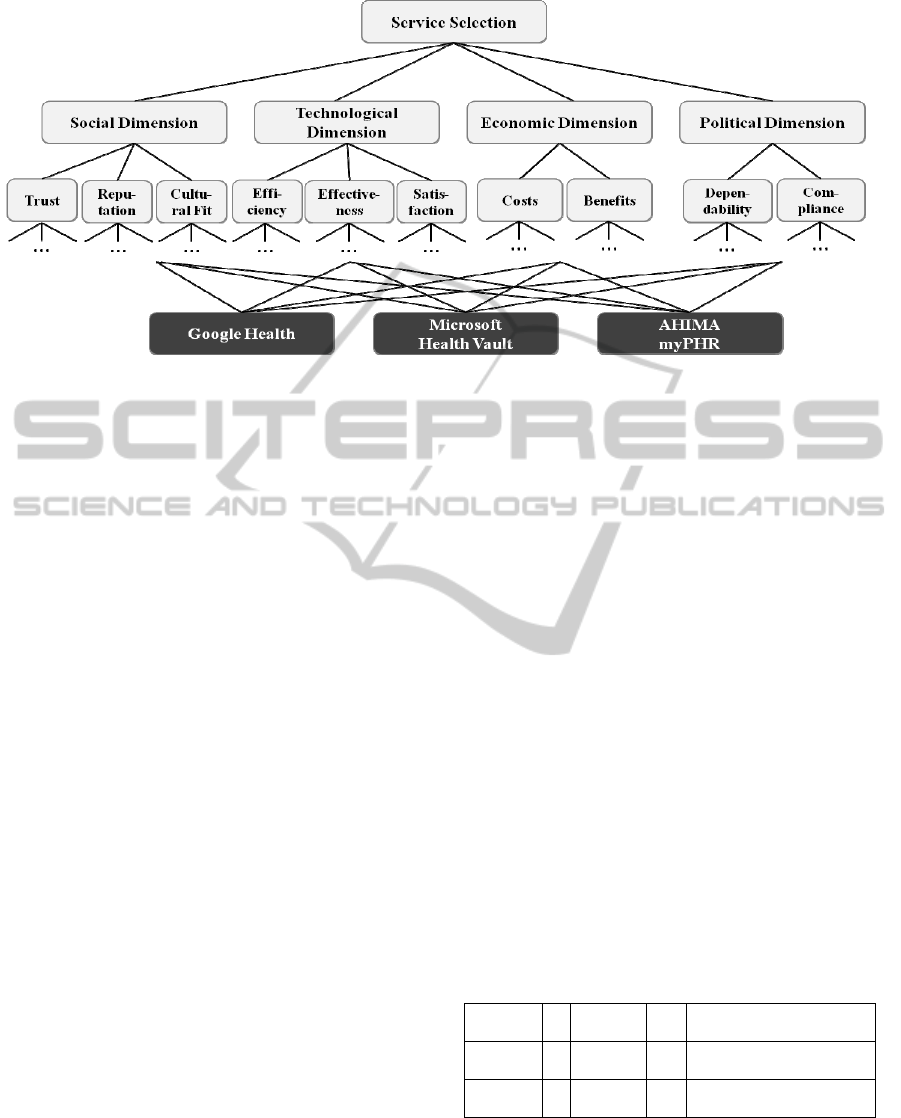

Figure 1: A Multi-Criteria Decision Model based on AHP and STEP.

section “Related Work”) are: its applicability in vast

variety of different areas (e.g. Golden, et al., 1989;

Handfield, et al., 2002), its reliance on easy-to-get

managerial data, its ability to reconcile

inconsistencies in managerial perceptions, and the

existence of various software tools (Handfield, et al.,

2002).

We describe the basics of the AHP technique in a

four step approach (on basis of Handfield, et al.,

2002; Saaty, 1980; Wu and Chang, 2007), but as our

approach suggests suitable sub-criteria, we mainly

focus on the second abstraction level (for detailed

information on the other levels please refer to Saaty,

1980). Indications therefore are discussed in the

previous section. In order to exemplarily explain the

AHP and especially the second abstraction level, the

illustration is based on the example of personal

health records (PHR) as we think that the choice of a

suitable PHR is complex and includes many

technical (e.g. provision of interfaces to mobile

devices, security and accessibility mechanisms, etc.)

as well as non-technical considerations (e.g.

credibility of provider, benefits of electronic vs.

paper-based health records, etc.). However, our

proposition is applicable to a wide area of domains.

As basis for this comparison we chose three

exemplary services: Google Health (GH), Microsoft

Health Vault (MHV), and AHIMA my Personal

Health Record (myPHR).

1st Step: Construction of the hierarchy: All

stakeholders can jointly construct the AHP

hierarchy, for instance, physically in a workshop or

over the Internet, e.g. on a Wiki (Wu and Chang,

2007). The AHP hierarchy typically consists of three

or four levels (can be extended to more levels, if

applicable): the goal (service selection), the relevant

criteria (cf. “STEP”), the relevant sub-criteria (as

introduced in the previous section), and the

alternatives to be evaluated (in this example: GH,

MHV, and myPHR; cf. Figure 1). The decision

makers need to agree on and describe the

characteristics of the components in the hierarchy.

2

nd

Step: Pair-wise comparison and estimation of

priorities: The stakeholders need to determine a

priority for each alternative (Step 2.1) and each

criterion (Step 2.2). The priority is a numerical

measurement of the power of a node in relation to

the other nodes on the same level and with respect to

the node(s) above it.

Step 2.1: Priorities of Alternatives: Each

alternative is pair-wise compared to all other

alternatives with respect to all related sub-criteria

and assigned weights, which reflect the relative

intensity of importance. The decision makers can

(among other variants) use a scale from 1 to 9: 1

being equally important, i.e. the two criteria

contribute equally to the objective and 9 referring to

favoring one criterion extremely over the other one;

Example, cf. Table 2).

Table 2: Alternatives compared with respect to TRUST.

GH 5 MHV 1

Wrt TRUST GH is fairly

favored over MHV

MHV 1 myPHR 7

myPHR strongly more

trusted than MHV

myPHR 4 GH 1

myPHR is moderately

more trusted than GH

There should be some evidence for the judgment

and weighting: the evidence could stem from, e.g.

past experience or the use of trial versions. The

weights are then transferred into matrices for each

sub-criterion: for each pair-wise comparison, the

WHAT IS THE RIGHT SERVICE? A MULTI-CRITERIA DECISION MODEL BASED ON 'STEP'

87

number that represents the greater weight (of a pair-

wise comparison) is directly rendered into the

matrix, whereas the reciprocal of that number is

transferred to matrix instead of the smaller number.

Then, for each sub-criterion priorities are calculated

for the alternatives by mathematically processing the

matrices. The estimation of priorities can be

accomplished in many ways (Table 3).

Table 3: Priorities of alternatives with respect to TRUST.

GH MHV myPHR Priority

GH 1 5 1/4 0.24

MHV 1/5 1 1/7 0.07

myPHR 4 7 1 0.69

Saaty (1980) recommends using a normalized

eigenvector approach, which is a proven method for

estimating the priorities (Golden, et al., 1989). Other

approaches are discussed, for instance, in Choo and

Wedley (2004). Software tools can take over the task

of the calculation.

Step 2.2: Priorities of Sub-Criteria: The same

procedure is applied to get the priorities for the sub-

criteria. That is to say, the sub-criteria are first pair-

wise compared with respect to their super-

criterion/criteria (cf. connecting lines between sub-

criteria and criteria) and relative weights assigned.

The weights are then transferred to matrices, from

which the priorities for each sub-criterion are

extracted.

Step 2.3: Priorities of Criteria: The same process

as for the sub-criteria is applied to the criteria,

resulting in one matrix that depicts the comparison

of the criteria with respect to the goal, the service

selection decision. Out of this matrix relative

weights are calculated.

Step 3: Calculation of the weight of each

Alternative with respect to the goal: In this step the

weights are multiplied and summated. The priorities

of the alternatives are multiplied with the priorities

of the sub-criteria and with those of the criteria,

which results in the overall priorities of each

alternative with respect to the goal. The priorities of

each alternative with respect to the goal are

summated over all criteria.

Step 4: Decision-Making: In accordance to the

AHP method, the alternative with the highest sum

should be chosen: that is the alternative with the

highest overall priority with respect to the goal. For

example, if a priority of 0.38 is calculated for GH,

0.11 for MHV, and 0.51 for myPHR, the service

myPHR should be selected.

5 CONCLUSIONS

The decision on selecting the right information-

intensive service should be made in a holistic

manner. However, we realized that the technological

dimension tends to be overemphasized. Therefore,

we suggest a multi-dimensional decision model for

complex service selection that dynamically assigns

relative importance to the social, technological,

economic and political dimension. Even if a service

may be ever so suitable from a technical perspective,

it may be ruled out due to a legal issue. Another

usual shortcoming is the limited perception of

different decision criteria. For instance, economical

considerations tend to be incomplete by focusing too

much on single issues such as the purchase of a

license, or the payment of a registration or activation

fee. A complete cost-benefit ratio can offer valuable

clues for complex service selection. For this reason,

we devised a framework for relevant second level

criteria: social (trust, reputation, cultural fit),

technological (efficiency, effectiveness,

satisfaction), and economic (costs, benefits), and

political (dependability, compliance).

Advantages of the method include the

accommodation of multiple criteria, the facilitation

of participation, the provision of a model to learn

from, to debate about, and to present to others, as

well as its simple and intuitive character and its

mathematical rigor. On the downside, the technique

can lead to a lengthy process, in particular if further

abstraction levels are added. To ensure a target-

aiming decision making process, one needs to be

careful not end up with an information overload. The

proposed method is therefore most suitable for the

selection of complex services with sweeping

consequences, e.g. if the service is very expensive, if

the service cannot be changed later on or if many

processes depend on the services. For a simple

service selection, heuristics may be the method of

choice as it the cheapest and fastest way to come to a

decision that is good enough. Future work should be

directed to automate repetitive decision-making as

good as possible. Still, it should be noted that

automated decision-making and the suggested

method is no substitute for clear thinking! The actual

process of the analysis can support the decision

makers in organizing and representing their

thoughts, but only clear thinking can prevent them

from an information overload and support them in

quick decisions.

ICE-B 2011 - International Conference on e-Business

88

REFERENCES

Alter, S., 2007. Service responsibility tables: a new tool

for analyzing and designing systems. In 13th Americas

Conference on Information Systems.

Alter, S., 2008. Service systems fundamentals: Work

system, value chain, and life cycle. IBM Systems

Journal, 47(1), 71-85.

Avizienis, A., Laprie, J.-C., Randell, B., Landwehr, C.,

2004. Basic concepts and taxonomy of dependable and

secure computing. IEEE Transactions on Dependable

and Secure Computing, 1(1), 11-33.

Baida, Z., Gordijn, J., Omelayenko, B., 2004. A shared

service terminology for online service provisioning. In

6th International Conference on Electronic

Commerce.

Billhardt, H., Hermoso, R., Ossowski, S., Centeno. R.,

2007. Trust-based service provider selection in open

environments. In 2007 ACM symposium on Applied

computing.

Birukou, A., Blanzieri, E., D’Andrea, V., Giorgini, P.,

Kokash, N., Modena, A., 2007. IC-service: a service-

oriented approach to the development of

recommendation systems. In 2007 ACM Symposium

on Applied Computing.

Brehm, S., Kassin, S., Fein, S., 2002. Social Psychology.

Boston. MA, Houghton Mifflin.

Castelfranchi, C., Falcone, R., 1998. Principles of trust for

MAS: Cognitive anatomy, social importance, and

quantification. In 3rd International Conference on

Multiagent Systems.

Chatterjee, S., Webber, J., 2004. Developing enterprise

web services: An architect’s guide. Upper Saddle

River: Prentice-Hall.

Choo, E., Wedley, W., 2004. A common framework for

deriving preference values from pairwise comparison

matrices. Computers & Operations Research, 31(6),

893-908.

Collier, D., Meyer, S., 2000. An empirical comparison of

service matrices. International Journal of Operations

& Production Management, 20(6), 705-729.

Cullen, S., Seddon, P. and Willcocks, L., 2005. Managing

outsourcing: the life cycle imperative. MIS Quarterly

Executive, 4(1), 229-246.

Ding, Q., Li, X. and Zhou, X. H., 2008. Reputation based

service selection in grid environment. In 2008

International Conference on Computer Science and

Software Engineering.

Ettenson, R., Turner, K., 1997. An exploratory

investigation of consumer decision making for

selected professional and nonprofessional services.

Journal of Services Marketing, 11(2), 91-104.

Farrell, J., Klemperer, P., 2007. Coordination and lock-in:

Competition with switching costs and network effects.

In M. Armstrong, R. Porter, eds. Handbook of

Industrial Organization, vol. 3. Amsterdam: Elsevier,

1967-2072.

Forest, F., Arhippainen, L., 2005. Social acceptance of

proactive mobile services: observing and anticipating

cultural aspects by a sociology of user experience

method. In 2005 Joint Conference on Smart Objects

and Ambient Intelligence.

Galizia, S., Gugliotta, A., Domingue, J. 2007. A trust

based methodology for web service selection. In

Proceedings of International Conference on Semantic

Computing, 193–200.

García, J., Ruiz, D., Ruiz-Cortés, A. 2010. A Model of

User Preferences for Semantic Services Discovery and

Ranking. The Semantic Web: Research and

Applications, 6089/2010, 1-14.

Gigerenzer G., 2004. Fast and frugal heuristics: the tools

of bounded rationality. In: Koehler D, Harvey N,

editors. Handbook of judgment and decision making.

Oxford, UK, Blackwell, 62–88.

Gigerenzer, G., 2007. Gut Feelings: The Intelligence of

the Unconscious. New York, Penguin Books.

Golden, B. L., Wasil, E. A., Harker, P. T., Alexander, J.

M., 1989. The analytic hierarchy process:

Applications and studies. Berlin, New York: Springer.

Guarino, N., 1998. Formal ontology and information

systems. In International Conference on Formal

Ontology in Information Systems.

Handfield, R., Walton, S. V., Sroufe, R., Melnyk, S. A.,

2002. Applying environmental criteria to supplier

assessment: A study in the application of the analytical

hierarchy process. European Journal of Operational

Research, 141(1), 70-87.

Hennig-Thurau, T., Gwinner, K. P., Walsh, G., Gremler,

D. D., 2004. Electronic word-of-mouth via consumer-

opinion platforms: What motivates consumers to

articulate themselves on the Internet. Journal of

Interactive Marketing, 18(1), 38-52.

Hofstede, G., Hofestede, G. J., 2005. Cultures and

organizations: Software of the mind. New York:

McGraw-Hill.

Hu, H., 2010. Research on building key post competency

model. In 2010 International Conference on E-

Product, E-Service and E-Entertainment.

Janicke, H., Solanki, M, 2007. Policy-driven service

discovery. In Proceedings of the 2nd European Young

Researchers Workshop on Service- Oriented

Computing, 56–62.

Javalgi, R. G., White, D. S., 2002. Strategic challenges for

the marketing of services internationally. International

Marketing Review, 19(6), 563-581.

Krishna, S., Sahay, S., Walsham, G., 2004. Managing

cross-cultural issues in global software outsourcing.

Communications of the ACM, 47(4), 62-66.

Kugyt , R., Šliburyt , L., 2005. A standardized model of

service provider selection criteria for different service

types: A consumer-oriented approach. Inzinerine

Ekonomika-Engineering Economics, 3(43), 56-63.

Liu, W., 2005. Trustworthy service selection and

composition: Reducing the entropy of service-oriented

web. In 3rd IEEE International Conference on

Industrial Informatics.

Liu, Y., Ngu, A. H., Zeng, L. Z., 2004. QoS computation

and policing in dynamic web service selection. In 13th

International Conference on World Wide Web.

Manchala, D. W., 2000. E-commerce trust metrics and

WHAT IS THE RIGHT SERVICE? A MULTI-CRITERIA DECISION MODEL BASED ON 'STEP'

89

models. IEEE Internet Computing, 4(2), 36-44.

Maximilien, E. M., Singh, M. P., 2004. A framework and

ontology for dynamic Web services selection. IEEE

Internet Computing, 8(5), 84-93.

McEvily, B., Perrone, V., Zaheer, A., 2003. Trust as an

Organizing Principle. Organization Science, 14(1), 91-

103.

Menascé, D., Casalicchio, E., Dubey, V., 2008. A heuristic

approach to optimal service selection in service

oriented architectures. Paper presented at the

Proceedings of the 7th international workshop on

Software and performance, Princeton, NJ, USA.

Menascé, D., Casalicchio, E., Dubey, V., 2010. On

optimal service selection in Service Oriented

Architectures. Performance Evaluation. 67 (89, 659-

675.

Mirani, R., Lederer, A. L., 1998. An instrument for

assessing the organizational benefits of IS projects.

Decision Sciences, 29(4), 803-838.

Peng, G. C., Nunes, M. B., 2007. Using PEST analysis as

a tool for refining and focusing context for information

systems research. In 6th European Conference on

Research Methodology for Business and Management

Studies.

Rengger R, Macleod M, Bowden R, Drynan A., Blaney

M., 1993. MUSiC performance measurement hand

book. Teddington, UK: National Physical Laboratory.

Saaty, T. L., 1980. The analytic hierarchy process. New

York: McGraw-Hill.

Schroth, C., 2007. The internet of services: Global

industrialization of information intensive services. In

2nd International Conference on Digital Information

Management.

Seo, Y. Jeong, H., Song, Y, 2005. A study on web services

selection method based on the negotiation through

quality broker: A maut-based approach. Embedded

Software and Systems, 3605, 65–73.

Smoreda, Z., Thomas, F., 2001. Social networks and

residential ICT adoption and use. In EURESCOM

Summit 2001.

Sreenath, R., Singh, M., 2004. Agent-based service

selection. Web semantics: Science, services and agents

on the world wide web, 1(3), 261-279.

Sutterer, M., Droegehorn, O., David, K. (2008). UPOS:

User Profile Ontology with Situation-Dependent

Preferences Support. Paper presented at the

Proceedings of the First International Conference on

Advances in Computer-Human Interaction.

Vaidya, O. S., Kumar, S., 2006. Analytic hierarchy

process: An overview of applications. European

Journal of Operational Research, 169(1), 1-29.

Vargo, S. L., Lusch, R. F., 2004. The four service

marketing myths. Journal of Service Research, 6(4),

324-335.

Voros, J., 2001. Reframing environmental scanning: An

integral approach. Foresight, 3(6), 533-551.

Warner, A. G., 2010.

Strategic analysis and choice: A

structured approach. New York: Business Expert

Press.

Wang, P., Chao, K.-H., Lo, C.-C., Farmer, R., Kuo, P.-T.,

2009. A reputation-based service selection scheme. In

IEEE International Conference on e-Business

Engineering.

Wang, Y., Vassileva, J., 2007. Toward trust and reputation

based web service selection: A survey. International

Transactions on Systems Science and Applications,

3(2), 118-132.

Webster, J., Watson, R. T., 2002. Analyzing the past to

prepare for the future: Writing a literature review. MIS

Quarterly, 26(2), 13-23.

Wei, C., Chien, C., Wang, M. 2005. An AHP-based

approach to ERP system selection. International

Journal of Production Economics, 96(1), 47-62.

Wixom, B., Todd, P. A., 2005. A theoretical integration of

user satisfaction and technology acceptance.

Information Systems Research, 16(1), 85-102.

Wu, C., Chang, E., 2007. Intelligent web services

selection based on AHP and wiki. In IEEE/WIC/ACM

International Conference on Web Intelligence.

W3C Working Group, 2003. QoS for web services:

Requirements and possible approaches. Accessed 20

Jan 2011, http://www.w3c.or.kr/kr-office/TR/2003/

ws-qos.

Yu, H., Reiff-Marganiec, S., 2008. Non-functional

property based service selection: A survey and

classification of approaches. In 2nd Non Functional

Properties and Service Level Agreements in Service

Oriented Computing Workshop.

Yu, T., Zhang, Y., Lin, K.-J., 2007. Efficient algorithms

for Web services selection with end-to-end QoS

constraints. ACM Transactions on the Web, 1(1), 1-26.

ICE-B 2011 - International Conference on e-Business

90