ADDRESSING E-GOVERNMENT WEBSITE USABILITY

A Users’ Centred Evaluation

Zhao Huang and Laurence Brooks

School of Information System, Computing and Mathematics, Brunel University, Brunel, U.K.

Keywords: e-Government, e-Government website development, Usability, Users’ centred approach.

Abstract: The challenge of greater users’ participation with e-government remains a significant issue. E-government

website usability has been found to be one of the major reasons influencing users’ interaction, which needs

to be addressed when developing e-government. This empirical study evaluates a current e-government

website, to identify specific usability problems. Based on the identified problems, the design solutions are

proposed, redesigned and evaluated in order to develop a more usable e-government website. The results

indicate that with the proposed design solutions provision, the identified usability problems have been

addressed. Such improvements may promote overall usability of e-government and make better users’ task

performance. These are beneficial for designers to further develop their e-government usability.

1 INTRODUCTION

Traditionally, government organisations deliver their

information and services through three main

methods: face to face, telephone and postal\mail

services (Brown, 2003). However, such methods are

largely influenced by time and space limitations,

which sometimes make access to information

difficult and block users’ engagement. With the

widespread use of the Internet and web technology,

it can be argued that a fourth method to deliver

government services has been created – e-

government. This provides all types of government

information and services available online. In such an

environment, users can interact with government

services 24 hours a day, 7 days a week without

physical distance requirements. Since these

advantages have become apparent, governments

worldwide have rapidly developed e-governments,

which has now become a global phenomenon

(Jaeger, 2003). However, research indicates that the

actual use of information and services provided on

e-government websites faces a challenge (Donker-

Kuijer, 2010). Website usability issue is one of the

major reasons for the underuse of e-government. For

example, Holden et al. (2003) found that many users

do not become involved with government online

services because of difficulty in finding their

expected information on the site. Generally, website

usability refers to how useful and user-friendly the

site is. If websites fail to provide ease of use from a

design standpoint and frustrate users interaction with

government services, e-government will not be

accepted and used by users (Barker, 2009).

Therefore, this suggests that e-government may not

achieve greater users’ participation unless the

website usability is recognised and addressed.

However, current research has not paid enough

attention to evaluating the usability of current e-

government websites, especially identifying specific

problems. Even some studies that conduct usability

investigation lack empirical evidence to provide

concrete prescriptions for the identified usability

problems in order to develop more usable e-

government websites. Furthermore, an e-government

website is used by a wide range of users, who have

heterogeneous backgrounds in terms of skills,

experience and education. These users may have

different usability needs from e-government

websites, which may increase the difficulty for

designers in identifying users’ requirements of

usability. In order to overcome this difficulty, a

users’ centred approach is considered as an

appropriate method, which can involve users’

participation and address users’ point of view. By

doing so, it can be beneficial for designers to

understand users and their usability requirements.

Additionally, it can directly detect the e-government

features that can cause users to have the most

concerns about usability. Accordingly, there needs

173

Huang Z. and Brooks L..

ADDRESSING E-GOVERNMENT WEBSITE USABILITY - A Users’ Centred Evaluation.

DOI: 10.5220/0003272201730183

In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies (WEBIST-2011), pages 173-183

ISBN: 978-989-8425-51-5

Copyright

c

2011 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

to be more attention directed toward users’

evaluation of usability. In this way, it can provide

concrete prescriptions for developing more user-

centred e-government websites that can generate

greater users’ participation.

To this end, this study aims to evaluate the

usability of current e-government websites in the

UK, identifying existing usability problems.

Moreover, in order to fulfil a systematic evaluation,

based on the usability problems identified, this study

proposes a set of design solutions and evaluates the

effects of these proposed design solutions on the

identified usability problems. This approach

addresses design, evaluation and redesign processes

in e-government website development, which is also

reflected in user centred studies in HCI, where one

of the major tasks is with problem detection and

solutions provision to develop computer systems

(Kossak et al., 2001). To implement the usability

evaluation, an experimental study has been designed

based on users’ perception of Nielsen’s set of

usability heuristics to conduct a thorough and in-

depth e-government websites usability inspection. In

addition, in order to reveal users’ task performance

within the e-government websites evaluated, users’

performance is also measured by a number of

performance criteria through observation. By doing

so, a more comprehensive evaluation, which not

only provides an deep insight into e-government

website usability, but also show the levels of users’

interaction with the specific e-government website,

can be carried out.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows:

section 2 reviews the theoretical background to

indicate the importance of usability to e-government

websites. Section 3 describes the detailed design of

an empirical study with two linked experiments.

Section 4 presents and discusses the results from

experiment 1. Section 5 proposes the design

solutions in relation to the usability problems

identified. Section 6 shows the findings from

experiment 2. Conclusions and limitations are drawn

and future research suggested in section 7.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

In consideration of a dynamic area of e-government

and its application for the general public, e-

government can be defined as the use of the Internet,

especially web technology as a tool to deliver

government information and services to users (Muir

and Oppenheim, 2002). The main purpose for e-

government is to achieve better government, which

enables easier access, richer information, higher

quality services and more enjoyable experience

(OECD, 2003). Furthermore, other advantages of e-

government include improving the level of public

services, increasing cost-effectiveness in services

provision (Følstad et al., 2004), promoting user

engagement and strengthening trust between

government and users (Wang et al., 2005). Since

such huge power has been recognized by traditional

governments, e-government initiatives are evolving

from the national to the local level, and developed

worldwide.Thousands of e-governments have now

been established which make government

information and services available online (Steyaert,

2004). Users can conduct all government services

provided by the national and local levels via

information presentation, interaction, transaction and

integration (Layne and Lee, 2001).

Although there is a rapid development of e-

government, a challenging target for e-government

of how best to interact with users still remains

(Kossak et al., 2001). Among the various reasons,

usability has been found to be an important reason

influencing users’ interaction and adoption of e-

government (Baker 2009). In essence, usability is a

very broad concept (Gillan and Bias, 2001). It can be

simply defined as effectiveness, efficiency and

satisfaction (ISO, 1998). However, in order to obtain

more comprehensive understanding, usability can be

explained by multiple criteria. For example, Flavián

et al. (2006) described five elements in relation to

usability, which are the perceived ease of

understanding the structure of a system, simplicity

of use of the website, the speed of locating the item,

the perceived ease of navigating the site and the

ability of the users to control their movement within

the system. Moreover, usability can be used as a

measurement related to how useful and user-friendly

the system is. As such, it is no doubt that usability is

a key factor in determining the computer system

quality (Karahoca et al., 2010) and ensuring users’

engagement (Sauer and Sonderegger 2009). For

example, Anthopoulos et al. (2006) applied

participatory design to discover user-oriented e-

government services. The study addresses the

importance of users’ needs in order to guide service

delivery improvement. Usability has been found to

be the determinant in consideration of users’

requirements, because if users failed to access and

execute the proper service due to usability errors,

their dissatisfaction increased. Such dissatisfaction

may prevent users’ return to an e-government

website, and even that users do not recommend their

use to others.

WEBIST 2011 - 7th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

174

Furthermore, usability has a significant impact

on users’ preference and attitude. Lee and Koubek

(2010) investigated the effects of usability and web

design attributes on user preference. The study

found that a high level of usability results in a high

level of user preference towards the website. In

particular, user preference was largely dependent

upon web attributes in terms of content arrangement,

navigation function, visual organisation, typography

and colour usage. Additionally, Casaló et al. (2008)

demonstrated that website usability not only has a

positive influence on user attitude, but also builds

user trust in the website loyalty formation process.

Similarly, Barnes and Vidgen (2004) observed

users’ interaction with an online government tax

self-assessment facility. The findings show that

users’ activities, such as online submission of self-

assessed tax returns and information seeking are

largely concerned with usability, navigation and site

communication. In order to generate greater users’

interaction, there is a need to not only understand the

usability requirements of users, but provide tailored

solutions to improve the usability of e-government

websites. These studies suggest that without

addressing usability in sufficient level in e-

government website design, e-government will not

be fully used and accepted by the widest range of

users. Accordingly, it is important to evaluate the

usability of current e-government websites, identify

existing problems and provide proposed design

solutions in order to further develop e-government

usability.

3 METHODOLOGY

Having established that that usability is an important

factor in e-government website development, an

empirical study was conducted with two linked

experiments. Experiment 1 aimed to evaluate

usability of a target e-government website.

Experiment 2 looked to examine the proposed

design solutions regarding the usability problems

found in experiment 1. To conduct both

experiments, three research instruments were used:

the task sheet, the heuristic-based usability

questionnaire and the selected e-government

website. The task sheet details a set of tasks for

participants to perform. A heuristic-based usability

questionnaire was developed to identify the

participants’ perception of usability. The e-

government websites were selected as representative

of e-government and used to evaluate its usability.

3.1 Task Design

To conduct the evaluation, the participants were

required to complete a set of practical tasks on an e-

government website. Such tasks are representative

activities that users would be expected to perform

with an e-government website. Based on relevant

studies (Shareef et al., 2011), there are two levels of

e-government services. The first level relates to the

publishing or static stage, which involves users’ one-

way communication, such as searching information,

downloading forms and publishing information. The

second level refers to the interaction stage, which

contains two-way communication, such as council

tax payment, online service registration and online

school application. According to these services

categories, the set of tasks have been designed to

represent different types of interaction that users

normally engage in with e-government (for details of

experiment 1 see Table 1). A similar set of tasks

were also developed for experiment 2. However, the

specific tasks content were different from the tasks

used in experiment 1 in order to avoid the influence

of experience from the participants’ performance in

experiment 1.

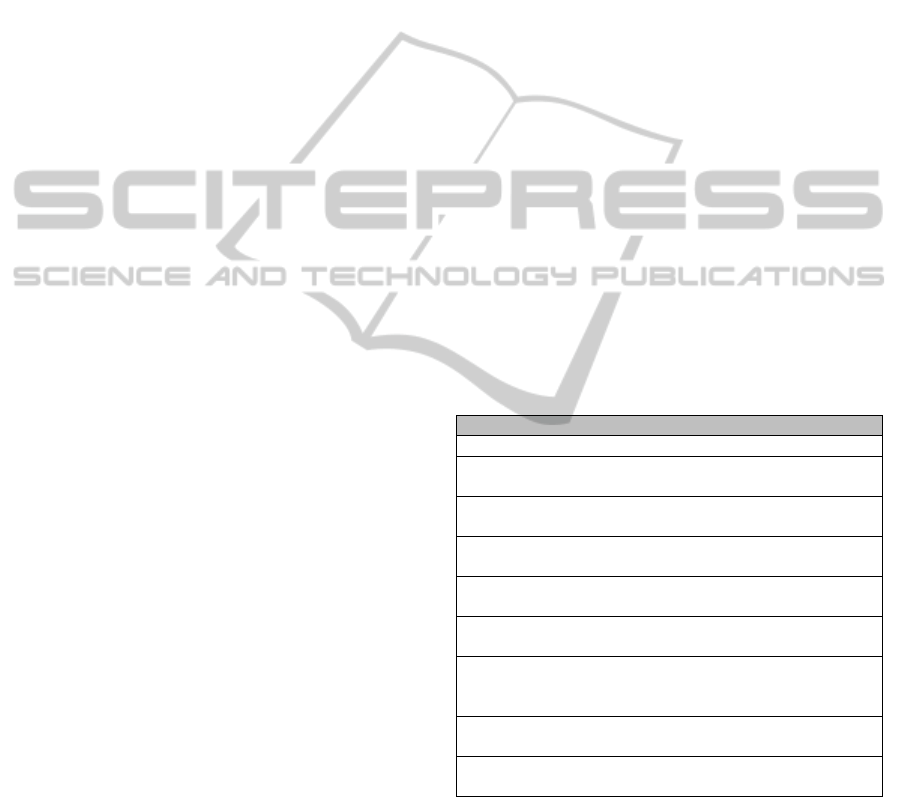

Table 1: e-Government practical tasks for London

Authority 1.

No. Task Ser. Category

1 Find the names of the councillors one-way

2 Find the news about £1.5 million for

new local authority housing

one-way service

3 Find the contact details of LA 1,

especially the telephone numbers

one-way service

4 Use the search engine on this site to

find how to join a local library

one-way service

5 Find the introduction information

about LA 1

one-way service

6 Use “A-Z services” to find the

parking tickets information

one-way service

7 Sign in the system, and fill in “an

online enquiry form” to query how to

get a student discount

two-way service

8 Fill in a “compliments form”

reporting no street lamp

two-way service

9 Please download the document of

council tax 2009/2010

one-way service

3.2 Usability Questionnaire

A heuristic-based questionnaire was used to measure

the participants’ perception of usability of the target

e-government website. The design of this

questionnaire is based on Nielsen’s set of usability

heuristics (1994). The questionnaire design consists

of three stages: extension of heuristics, development

criteria and usability questionnaire design.

ADDRESSING E-GOVERNMENT WEBSITE USABILITY - A Users' Centred Evaluation

175

3.2.1 Extension of Heuristics

Nielsen’s (1994) set of heuristics (see Table 2) is

used as a starting point for evaluating e-government

websites usability since a growing number of studies

have proven its validity and usefulness (e.g.

Hvannberg et al., 2007, Delice and Güngör, 2009).

However, such heuristics were developed many

years ago and used for general usability evaluation.

In order to fit with the particular requirements of e-

government websites, there is a need to derive

additional heuristics. Evidence from previous studies

indicates that where e-government is used by the

public, interoperability is important in terms of

information and service exchange (Garcia et al.,

2005); for example ensuring news is kept current

between e-government and government. In addition,

since e-government is used by diverse users who

have heterogeneous skills, therefore, e-government

should support and extend users with different skills

to access and complete services. Furthermore,

during users’ interaction with online services, e-

government should show respect for users at all

times (Reddick, 2005). Therefore, the existing

heuristics are extended by adding three new

heuristics: ‘Interoperability’, ‘Support users’ skills’

and ‘Respectful interaction with users’ (see Table 3).

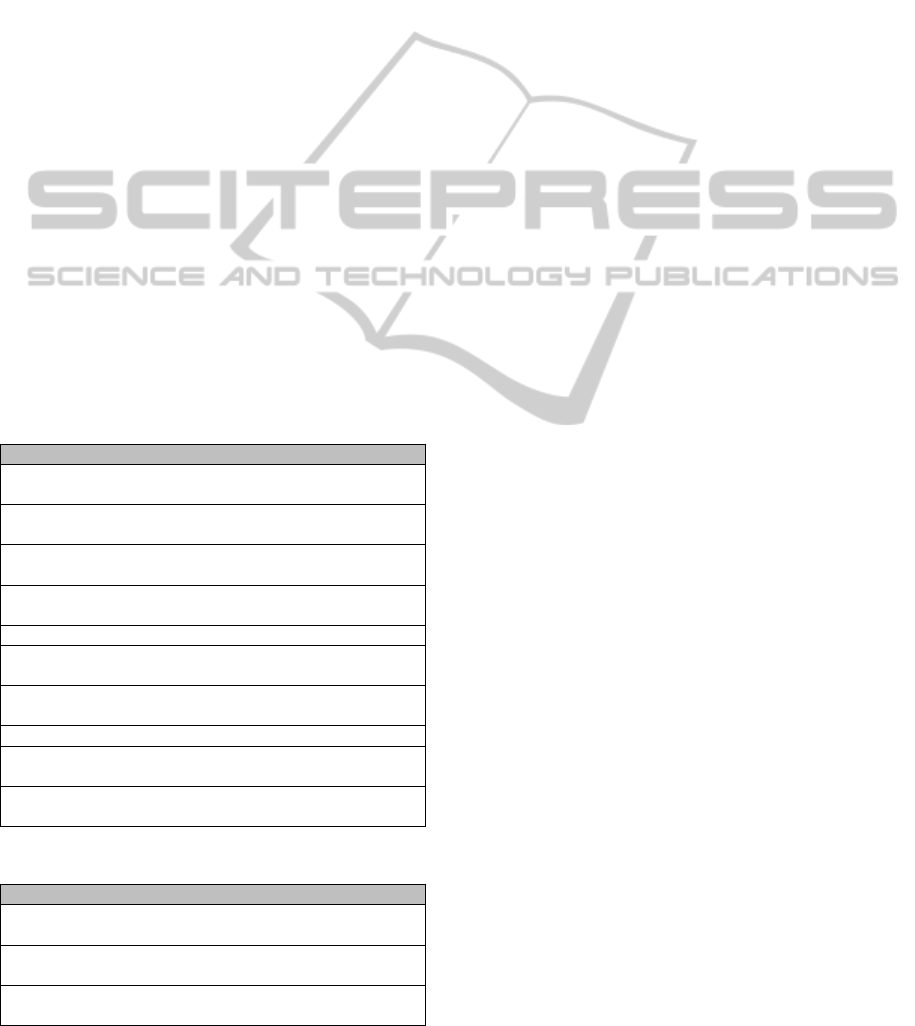

Table 2: Nielsen’s usability heuristics (1994).

Heuristics Interpretation

H1 Visibility of

system status

To keep users informed about what

is going on.

H2 Match system

with real world

To follow real-world conventions.

H3 User control and

freedom

To make undo and redo functions

available during interaction.

H4 Consistency and

standards

To keep the same design feature

through the site.

H5 Error prevention To support users to overcome errors.

H6 Recognition

rather than recall

To make information easily

remember.

H7 Flexibility and

efficiency of use

To allow users to tailor frequent

actions.

H8 Aesthetic design To make minimalist design.

H9 Help user

recover errors

To indicate the problem and suggest

a solution.

H10 Help and

documentation

To provide help to support user’s

task completion.

Table 3: Extended heuristics.

Extended heuristics Interpretation

H11 Interoperability To make all elements work as a

whole for user task completion.

H12 Support users’

skills

To support users with different

knowledge and background.

H13 Respectful

interaction

To present pleased design and

treat users with respect.

3.2.2 Development Criteria

Although Nielsen’s set of usability heuristics is

extended, it is still too general to develop a

questionnaire to evaluate usability, so that e-

government website usability would be evaluated

with enough depth. Furthermore, the lack of detailed

analysis may lead to failure in specific usability

problem identification. Therefore, associated criteria

for each heuristic needs to be developed. Such

criteria are developed from relevant usability (e.g.

Sonderegger and Sauer, 2010) and e-government

studies (e.g. Baker, 2009). These studies reveal a

number of elements that affect website usability and

users’ perception. Based on the analysis of these

elements, relevant criteria are identified and grouped

into corresponding heuristics. By doing so, it can

provide a step-by-step approach to closely focus on

the specific usability aspects. In addition, relevant

questions can be precisely developed.

3.2.3 Usability Questionnaire Design

A usability questionnaire was designed for capturing

the participants’ perception of usability. The reasons

behind choosing a questionnaire are that it can drive

the participants directly to the research topics, which

enables the participants to clearly see the focus. In

addition, with an anonymous response style, it

encourages respondents to offer their truthful reply.

Furthermore, using a questionnaire can ensure that

the same questions are delivered to each participant

and their responses can be obtained quickly. In order

to capture users’ perception of usability before and

after the redesign and to control the variables to

support comparative analysis, the same

questionnaire is used for the participants in both

experiments 1 and 2.

3.3 e-Government Website Selection

Among a variety of e-government websites, a local

e-government website in the UK is selected in this

study for a number of reasons. Firstly, the local level

of e-government website is the closest level to users.

Secondly, local e-government websites are

frequently used by the general public, since local e-

government provides more information and focuses

on the needs of users in accessing information and

services (Reddick, 2009). Thirdly, the local level of

e-government can significantly indicate the effect of

e-government on users (Tolbert and Mossberger,

2003). Fourthly, previous studies show the big

challenges at the local level of e-governments (Yang

and Paul, 2005) and its website design (Henriksson

WEBIST 2011 - 7th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

176

et al., 2007). Thus, the local e-government website

(London Authority 1) is used in this study. This

London Authority 1 contains rich information and

provides a variety of government services available

on the site.

3.4 Participants

To conduct heuristic evaluation, Nielsen and Molich

(1990) found that three participants can detect half

of the major problems. Furthermore, Virzi (1992)

suggested that 80% problems can be identified with

between 4 and 5 participants and 90% of problems

can be found with 10 participants in usability

evaluation. Moreover, Dumas and Redish (1999)

argued that additional participants are less and less

likely to reveal new problems and pointed out that

the most appropriate number of participants is

between 6 and 12. As such, 12 participants were

recruited to take part in the evaluation, participating

in both experiments 1 and 2. These participants were

recruited in public places, such as local libraries,

leisure centres, universities, and found to be

enthusiastic to do the evaluation. The participants

found in public places can be assumed to be

representative of the public and that they do

normally use an e-government website.

3.5 Experimental Evaluation

Procedure

In both experiments, each participant follows the

same evaluation process: free-flow inspection, task-

based interaction and usability questionnaire. Free-

flow inspection allows users to freely look through

the e-government website many times. They can

focus on either the overall website or the specific

website elements. As such, users can build their

initial interaction with the e-government website and

their general perception can be developed. Then,

task-based interaction requires the participants to

complete a set of tasks. While the participants

perform these tasks, their performance was observed

according to a number of performance criteria,

including the amount of online help required; time

spent completing tasks; number of steps to finish

tasks and number of successful tasks completed.

Having completed all tasks, the participants are

asked to fill in the usability questionnaire to indicate

their judgment of usability of the target e-

government website.

4 RESULTS OF EXPERIMENT 1

As indicated, the aim of experiment 1 is to evaluate

usability of the target e-government website. The

following section presents the results in terms of

users’ perception and performance. The former uses

the results from the questionnaires to indicate

usability assessment, while, the latter is measured by

a set of performance criteria to indicate the level of

users’ interaction with the target e-government

website. To conduct data analysis, the one-sample T-

test is considered as an appropriate technique for

experiment 1. More specifically, the one-sample T-

test is applied to determine whether there is a

significant difference between users’ perception of

overall usability and specific usability features. If a

difference is indicated, then the mean score of the

specific usability features is greater than the mean

score of the overall usability features and these can

be seen as ‘usability strengths’. Similarly, where the

mean score of the specific usability features is less

than mean score for the overall usability features,

then these usability elements have been selected as

the ‘usability problems’. In addition, a lower mean

score indicates a more serious problem. Statistical

analysis of the data is conducted using SPSS for

windows (version 13). The significance value is

defined as less than 0.05.

4.1 User’ Perception

Generally, the target e-government website appears

to be clear and fairly straightforward, and it is easy

to operate the e-government website. Each page

always follows the same display format, which is

helpful to build website consistency. The site’s

functionality supports users to complete most tasks.

A title on every page clearly indicates the subject of

the content, so that users can quickly capture the

subject information of the page and locate

information to meet their needs. Moreover, key

information is always placed in a central location on

the page, which can support users quickly searching

for information. Furthermore, it is quick to change

the particular data in a previous section so users do

not need to retype all the data when they go back. In

addition, forward and backward choices are always

available within the different fields of the site, so

that users can easily guide their movement in

information searching.

However, the results obtained from the

questionnaires also indicate a number of usability

problems (see Table 4). Among them, the most

serious usability problem found is that users are

ADDRESSING E-GOVERNMENT WEBSITE USABILITY - A Users' Centred Evaluation

177

confused by links that have many different colours.

Link colour is used to present different resources

within the site. Links with limited colours can

visually help users distinguish between the

resources, so as to easily identify relevant subject

information. As indicated by Kappel et al. (2006),

users with limited colour vision can quickly

recognise the differences among subjects. In

contrast, failure to provide limited link colours can

visually influence resource recognition, so that users

may feel it difficult to locate target information

among subject content.

Table 4: User’ perception of usability problems.

Usability problems Mean (SD)

Confusion by links that have

many different colours.

2.58 (0.669)

Significance T=-6.511, P=0.000

Subject categories are presented

without a logical order.

2.83 (1.030)

Significance T=-3.386, P=0.006

Links already visited are not

clearly marked.

2.92 (1.084)

Significance T=-2.952, P=0.013

Information is unbalanced

between breadth and depth.

3.00 (0.853)

Significance T=-3.412, P=0.006

(SD=Std. deviation)

The next usability problem is that subject

categories are presented without a logical order. A

logical order is used to indicate a sequence of

information organization, which supports users

having a sensible way to scan subject. It assists

users’ understanding of the overall subject

arrangement and reduces memory load problems.

Brinck et al. (2002) suggested that when topics are

arranged with a particular order, users are able to

easily locate items; remember items of interest

viewed previously. On the contrary, when subject

categories are presented without a logical order,

users may feel it is difficult to find target subjects

among the categories.

Furthermore, the usability problem found is that

links already visited are not clearly marked. Marking

visited links is used to support users’ ability to

distinguish which parts of the site they have already

visited and which parts remain to be explored. As

such, it can help users to locate information during

information searching. As indicated by Nielsen

(2000), visited links that have been clearly marked

can provide a sense of structure and location in the

site and enable users to quickly find the subject

information. However, failure to mark visited links

can weaken navigational recognition, which results

in users visiting the same place repeatedly, or even

abandoning searching purpose prematurely.

Finally, a usability problem found is that the

information arrangement is out of balance between

breadth and depth. Breadth and depth are used to

distribute e-government content by designing a

number of subject categories and a number of

information levels. A medium condition of breadth

and depth is considered as an optimal trade-off,

which can help information retrieval (Larson and

Czerwinski, 1998). It is because the appropriate

number of categories displayed can keep content

from getting cluttered and reduce the chance that

users are confused by a vast number of options.

While, as the moderate levels of information is

designed, it can avoid over-length subject

information through the site so that users can follow

a short path into the site in order to find the detailed

information. However, as suggested by Larson and

Czerwinski (1998), unbalanced breadth and depth

can cause problems in information acquisition. In

such conditions, users are frustrated by increasing

levels of depth or feeling lost in content space, when

there are a large numbers of categories. As such, the

problem that information arrangement is out of the

balance between breadth and depth in London

Authority 1 may cause more difficulties and errors

for users searching for available information

resources on a page and locating detailed

information through multiple information levels.

4.2 Users’ Performance

Having provided the participants’ perception of

usability, in order to indicate the level of the

participants’ interaction with the e-government

website, users’ performance is measured based on a

set of performance data, including the amount of

online help required; average time spent completing

all tasks; average number of steps to finish tasks and

ratio of successful tasks completed. More

importantly, this performance measurement in

experiment 1 will be used as the baseline to compare

users’ performance in experiment 2. Table 5

presents the participants’ performance with the

target e-government website. Overall, all

participants are able to complete most of the tasks

assigned. In addition, during their performance, the

participants’ required some assistance through

online help information. The time spent and the

steps used for completing all tasks are 16.209

(minutes) and 50.167 (number of steps) with

standard deviation of 8.102 and 16.297 respectively.

WEBIST 2011 - 7th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

178

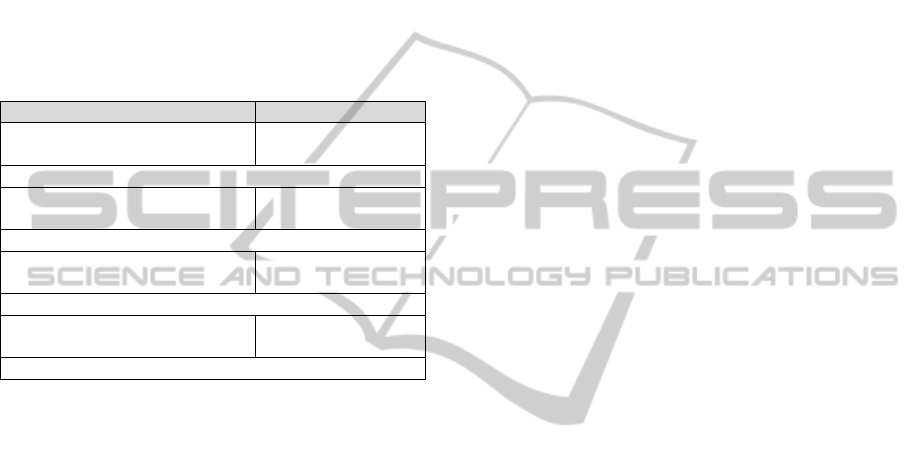

Table 5: Experiment 1: users’ performance results.

Mean Std. Deviation

Online helps required 0.000 0.000

Steps used 50.167 16.297

Successful tasks completion 1.065 0.088

Time spent for all tasks 16.209 8.102

5 DESIGN OF THE PROPOSED

SOLUTIONS

The findings in experiment 1 indicate a number of

usability problems that have been identified in the

target e-government website. These problems

suggest that usability has not been considered in

sufficient detail in e-government website design. For

an e-government to be accepted and used by the

widest range of users, the e-government website

should improve its usability to support users’

interaction with e-government. As indicated by

Garcia et al. (2005), improving usability of e-

government can enhance service effectiveness and

users’ satisfaction, which may involve more users’

participation. As such, it is important to develop

more usable e-government websites that can meet

different users’ requirements. In this vein, this study

takes further action by providing the proposed

design solutions in relation to the usability problems

found in experiment 1.

Usability problem 1 (UP1): Users are confused with

links that have many different colours

A limited number of link colours can visually help

users to distinguish resource differences so as to

easily identify relevant subject information.

Conversely, links with many different colours

hamper resource recognition, which may result in

users’ difficulty with information identification. As

such, designers of e-government websites should

consider applying the minimum number of link

colours, thereby supporting users’ subject

recognition during information seeking. One

proposed design solution is to reduce link colours

used in London Authority 1. In this way, it may

reduce users colour visual confusion and visually

support users when locating information objects.

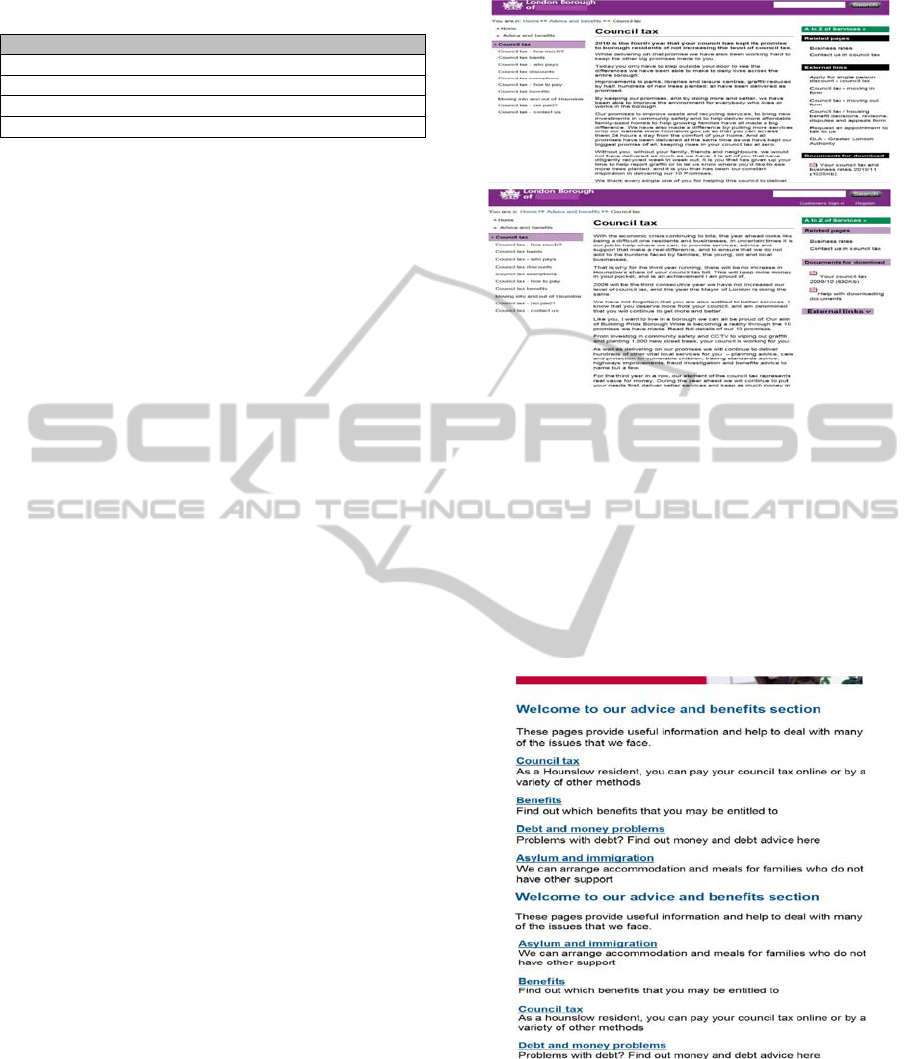

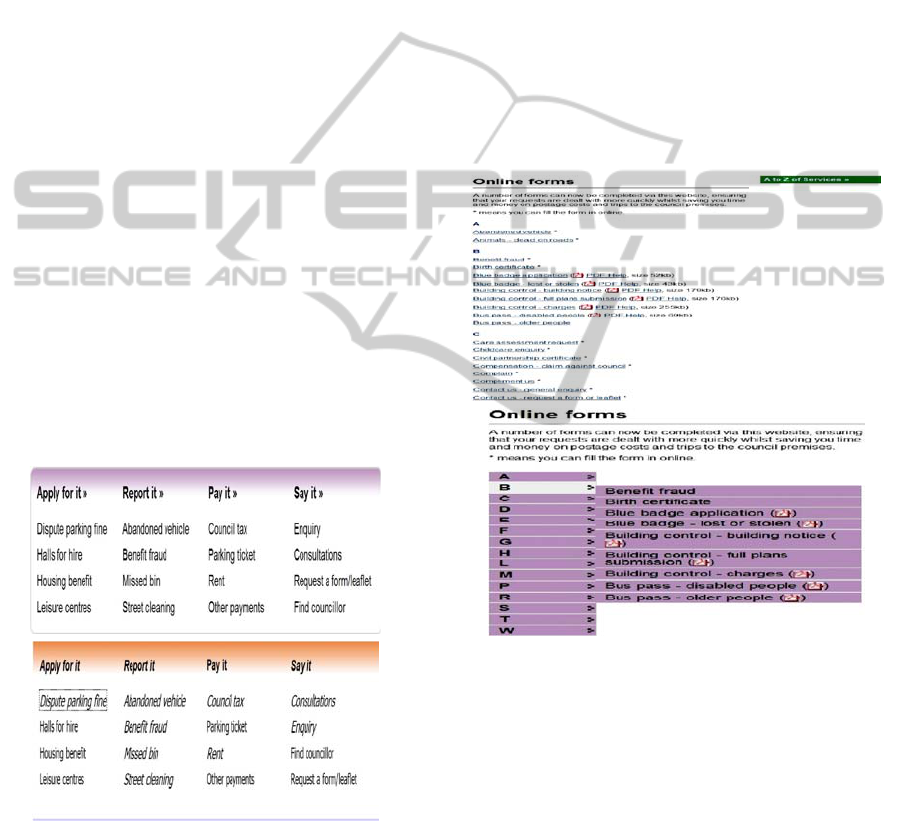

Figure 1a presents an example of links that have

many different colours in London Authority 1.

Whereas, Figure 1b shows that some link colours are

reduced in the redesigned London Authority 1

website.

a)

b)

Figure 1: UP 1 and the Proposed Design Solution.

Usability problem 2 (UP2): Subject categories are

presented without a logical order

A logical order is used to show a sequence of

information arrangement, which helps users quickly

scan subject information to identify objects and

reduce memory load problems. Similarly, failure to

present subject categories with a logical order

hinders information arrangement, which may lead to

complexity of information seeking.

a)

b)

Figure 2: UP 2 and the Proposed Design Solution.

Accordingly, designers of e-government websites

should consider organising subject categories in a

particular order in order to support users identifying

a sensible way to scan subject information. One

proposed design solution is to arrange subject

categories in an alphabetical order on each page of

ADDRESSING E-GOVERNMENT WEBSITE USABILITY - A Users' Centred Evaluation

179

London Authority 1. In this way, users may quickly

understand the overall subject arrangement and

easily identify relevant information to meet their

needs. Figure 2a shows that initially, the subject

categories are randomly presented on London

Authority 1. However, Figure 2b indicates an

example of the subject categories that are organised

and presented in an alphabetical order.

Usability problem3 (UP3): Links already visited are

not clearly marked

Marking visited links is used to indicate which parts

of the site users have already visited and which parts

remain to be explored. It can help users build the

sense of structure and location in the site, and

navigate them quickly to their target information.

However, when visited links are not clearly marked,

it weakens the site’s navigational recognition, so that

users may very likely visit the same page repeatedly

and have difficulty locating information. Therefore,

designers of e-government websites should consider

providing an approach that will help users recognise

the unvisited and visited links within the site during

the information seeking process. One proposed

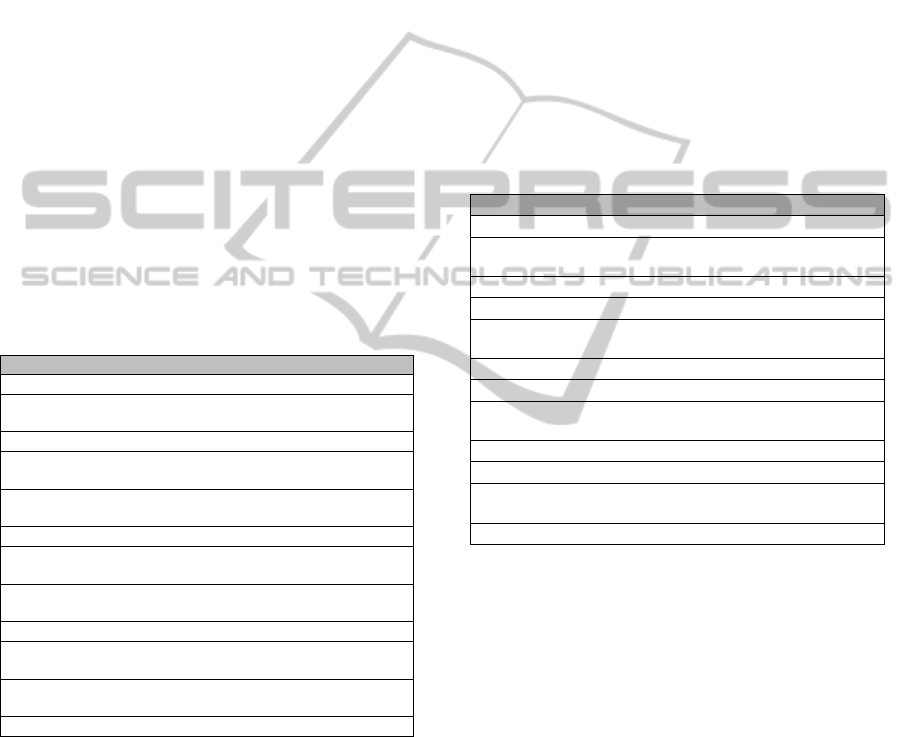

design solution is to mark visited links in italics

within London Authority 1. As shown in Figure 3a,

initially, the visited links in London Authority 1

have not been clearly marked. However, Figure 3b

shows that the visited links are clearly marked in

italics on the site.

a)

b)

Figure 3: UP 3 and the Proposed Design Solution.

Usability 4 (UP4): Users get lost due to being given

too many choices during information seeking

An appropriate number of options can be used to

keep content from getting cluttered and reduce the

chance that users are confused by a large number of

choices. Hence, it helps information retrieval. On the

contrary, an excessive number of choices may cause

difficulty in information acquisition (Nielsen, 2000),

so that users may feel frustration when searching for

information in a particular content space. Therefore,

designers of e-government websites should consider

providing an approach that will allow users to feel

comfortable with the number of subject options. One

proposed design solution is to design a drop-down

menu for each subject category that visually hides its

sub options. When users move the mouse to the

subject category, a type of stretch sub list is used to

present the various sub options associated with this

subject category. In this way, the number of choices

is visually reduced on the page, which is not only

helpful in preventing content from getting cluttered,

but also beneficial for users to read and locate

information (see Figure 4a and 4b).

a)

b)

Figure 4: UP 4 and the Proposed Design Solution.

6 RESULTS OF EXPERIMENT 2

Have provided the design solutions above, to

investigate the effects of the proposed design

solutions on the usability problems found,

experiment 2 is conducted. This section provides the

results of experiment 2 in terms of users’ perception

and performance. In order to control the variables

under the same conditions between experiments 1

and 2, the same research instruments used in

experiment 1 are used in experiment 2; including the

questionnaire, the task sheet, the participants and the

procedure. However, in order to avoid the

WEBIST 2011 - 7th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

180

participants learning from their experience with

experiment 1, the tasks designed for experiment 2

focus on different service activities, but remain the

same type of tasks as used in experiment 1. The

results obtained from the participants’ perception

and performance is analysed by using a paired-

sample T-test.

6.1 Users’ Perception

Table 6 reveals users’ perception in experiment 2.

Regarding the specific usability feature of links

having many different colours, and subcategories not

being present with a logical order, a significant

difference is found between experiments 1 and 2.

However, although no significant difference is

indicated between experiments 1 and 2 with respect

to the usability problems of visited links not being

clearly marked and many choices being given during

information seeking, the results still show that the

participants’ assessments are influenced after the

design solutions have been applied to the redesigned

London Authority 1.

Table 6: Experiment 2: user’ perception results.

Experiment 1 Experiment 2

Confusion with links that have many different colours.

Mean 2.58 4.33

Std. Deviation 0.669 0.492

Significance T= -8.042, P=0.000

Difficult to choose the option in subcategories because no

logical order of sub options is used in subcategories.

Mean 2.83 4.17

Std. Deviation 1.030 0.577

Significance T= -4.000, P=0.002

It clearly indicates which choices/links are already visited

because they have been marked.

Mean 2.92 3.58

Std. Deviation 1.084 1.165

Significance T= -1.685, P=0.120

I sometimes get lost due to being given too many choices

over sequences.

Mean 3.00 3.75

Std. Deviation 0.853 1.215

Significance T= -1.567, P=0.145

In other words, for each specific usability feature,

the participants’ assessment is significantly changed

in experiment 2. As indicated earlier, the proposed

design solutions have been applied to the target e-

government website in experiment 2. The results

show that the usability problems perceived in

experiment 1 have been improved in the redesigned

e-government website. Therefore, the findings

suggest that the proposed design solutions have

improved the usability problems identified in

experiment 1. In addition, it increases overall users’

perception of usability of London Authority 1.

6.2 Users’ Performance

Given that the usability problems have been

improved by the proposed design solutions in the

redesigned London Authority 1, and in order to

reveal the level of users’ interaction with the

redesigned London Authority 1, users’ performance

in experiment 2 is also measured based on the same

performance criteria used in experiment 1. By

focusing on such criteria, it comparatively analyses

performance results before and after the proposed

design solutions have been applied in experiments 1

and 2 respectively. The detailed results are presented

in the following subsections.

Table 7: Experiment 2: users’ performance results.

Experiment 1 Experiment 2

Total time spent completing tasks

Mean 16.209 10.009

Std. Deviation 8.102 2.334

Significance T=2.523, P=0.028

Number of steps to finish tasks

Mean 50.167 40.333

Std. Deviation 16.297 4.1141

Significance T=2.046, P=0.045

The amount of online help required

Mean 0.000 0.000

Std. Deviation 0.000 0.000

Significance T= N/A, P= N/A

Successful tasks completion

Mean 1.065 1.000

Std. Deviation 0.088 0.000

Significance T= N/A, P= N/A

Table 7 shows the participants’ performance in

experiments 1 and 2. As indicated in Table 7, the

results of the Paired-Samples T-test reveals a

significant difference in terms of the time spent

completing all tasks between experiments 1 and 2

(T=2.523, P=0.028). More specifically, the

participants in experiment 2 use less time to

complete all tasks, compared with experiment 1.

In addition, a significant difference in terms of

steps used for all tasks completion is found between

experiments 1 and 2 (T=2.046, P=0.045). In detail,

the participants in experiment 2 take fewer steps to

finish all the tasks than those who are in experiment

1.

The results of Paired-Samples T-test show that

the difference in terms of number of online help

actions required for all tasks completion is not

significantly different between experiments 1 and 2.

However, according to the mean score, it emerges

that the participants in experiment 2 required less

ADDRESSING E-GOVERNMENT WEBSITE USABILITY - A Users' Centred Evaluation

181

online help to complete all the tasks compared with

experiment 1. Similarly, although the difference in

terms of number of successful tasks completion is

not significant between experiments 1 and 2, the

mean score also indicate that the participants finish

more tasks in experiment 2 than experiment 1.

Based on the performance results, it seems that

the participants’ performance with the redesigned

London Authority 1 is significantly enhanced in

experiment 2. These are also reflected in the results

of users’ perception, which reveal that the proposed

designed solutions on the redesigned London

Authority 1 have improved the usability problems

identified in experiment 1. A possible explanation is

that since the proposed design solutions have

improved the usability problems, it increases the

overall users’ perception of usability, which in turn,

makes for better users’ performance. This is also

supported by previous studies (e.g. Amoako-

Gyampah, 2007; Baker, 2009), which suggested that

the overall users’ perception of usefulness and ease

of use has positively influenced users’ performance

and intention to use the technology.

7 CONCLUSIONS

This study has evaluated the usability of one existing

UK e-government website, which uncovered a

number of usability problems. This suggests that this

e-government website has much room to improve its

usability. As such, this study offers and assesses a

set of proposed design solutions regarding the

usability problems found for the target e-government

website. The results show that the proposed design

solutions have improved the usability problems

identified. More significantly, after the proposed

design solutions have been implemented in the

redesigned e-government website, users’ task

performance has been also significantly improved.

Accordingly, it suggests that the proposed design

solutions may improve the overall users’ perception

of usability of the target e-government website,

which makes for better users’ performance.

Therefore, it is important to show that usability of e-

government websites meet users’ needs, so that

users’ interaction with e-governments may be

promoted. To achieve this goal, this study conducts

a user centred approach, which can help understand

the usability requirements of users. In addition, this

study combines usability evaluation and redesign of

an e-government website, which provides guidance

for designers to identify existing usability problems

and offer specific prescriptions for further usability

improvement of e-government websites. The final

target is to develop more usable e-government that

can generate greater users’ participation in e-

government.

However, there are also some limitations in this

study. For example, this study only evaluates one e-

government website, as an example. Further

research may be conducted with more distributed e-

government websites in the UK. Another limitation

relates to the redesigned e-government website in

experiment 2. The redesigned e-government website

is based on the target e-government website used in

experiment 1, keeping the same structure, layout and

content. However, the redesigned e-government

website does not include all the website pages from

the target e-government website. This may influence

users’ general perception when they conduct a free-

flow inspection. In addition, this study applies a set

of extended heuristics to evaluate usability of current

e-government websites. In order to support

designers’ usability knowledge and skills for e-

government development, there is also a need to

conduct future study to develop usability guidelines

that contain detailed usability design features,

specifically for the development of better e-

government websites.

REFERENCES

Amoako-Gyampah, K., 2007. Perceived usefulness, user

involvement and behavioural intention: an empirical

study of ERP implementation, Computer in Human

Behavior, 23, 1232-1248.

Anthopoulos, L. G., Siozos, P., Tsoukalas, I. A. 2006.

Applying participatory design and collaboration in

digital public services for discovering and re-designing

e-government services, Government Information

Quarterly, 24(2), 353-376.

Barker, D. L. 2009. Advancing e-government performance

in the United States through enhanced usability

benchmarks, Government Information Quarterly, 26,

82-88.

Barnes, S. J., Vidgen, R., 2004. Interactive e-government

services: modelling user perceptions with eQual,

Electronic Government, 1(2), 213-228.

Brinck, T., Gergle, D., Wood, S. D. 2002. Usability for the

web: designing web site that work, Morgan Kaufmann

Publishers, San Francisco, CA.

Brown, M. M. 2003. Digital government innovation,

School of Government, University of North Carolina

at Chapel Hill, Retrieved from

http://ncinfo.iog.unc.edu/pubs/electronicversions/pdfs/

dgib0301.pdf.

Casaló, L., Flavián, C., Guinalíu, M. 2008. The role of

perceived usability, reputation, satisfaction and

consumer familiarity on the website loyalty formation

WEBIST 2011 - 7th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

182

process, Computers in Human Behavior, 24(2), 325-

345.

Delice, E., Güngör, Z., 2009. The usability analysis with

heuristic evaluation and analytic hierarchy process,

International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics, 39(6),

934-939.

Donker-Kuijer, M. W., Jong, M., Lentz, L. 2010. Usable

guidelines for usable websites? an analysis of five e-

government heuristics, Government Information

Quarterly, 27, 254-263.

Dumas, J. S., Redish, J. C., 1999. A practical Guide to

usability testing, Intellect Ltd, USA.

Flavián, C., Guinalĭu, M., Gurrea, R. 2006. The role

played by perceived usability, satisfaction and

consumer trust on website loyalty, Information and

Management, 43, 1-14.

Følstad, A., Jørgensen, H. D., Krogstie, J., 2004. User

involvement in e-government development projects,

Nordic Conference on Human-Computer Interaction,

82, 217 - 224.

Garcia, A. C. B., Maciel, C., Pinto, F. B. 2005. A quality

inspection method to evaluate e-government sites,

Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 3591, 198-209.

Gillan, D. J., Bias, R. G. 2001 usability science I:

foundations, International Journal of Human

Computer Interaction, 13(4), 351-372.

Henriksson, A., Yi, Y., Frost, B., Middleton, M., 2007.

Evaluation instrument for e-government websites,

International Journal of Electronic Government, 4(2),

204-226.

Holden, S. H., Norris, D. F., Fletcher, P. D. 2003.

Electronic government at the local level: progress to

date and future issue, Public Performance and

Management Review, 26(4), 325-344.

Hvannberg, E. T., Law, E. L., Larusdottir, M. K., 2007.

Heuristic evaluation: comparing ways of finding and

reporting usability problems, Interacting with

Computers, 19(2), 225-240.

ISO 9241-11, 1998. Ergonomic requirements for office

work with visual display terminals part II: guidance on

usability, International Organization for

Standardization.

Jaeger, P. T. 2003. The endless wire: e-government as

global phenomenon, Government Information

Quarterly, 20(4), 323-331.

Karahoca, A., Bayraktar, E., Tatoglu, E., Karahoca, D.

2010. Information system design for a hospital

emergency department: a usability analysis of software

prototypes, Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 43,

224-232.

Kappel, G., Pröll, B., Reich, S., Retschitzegger, W. 2006.

Web engineering, the discipline of systematic develop-

ment of web applications, John Wiley & Sons.

Kossak, F., Essmayr, W., Winiwarter, W., 2001.

Applicability of HCI research to e-government, 9th

European Conference on Information Systems, 957-

968.

Larson, K., Czerwinski, M. 1998. Web page design:

implications of memory, structure and scent for

information retrieval, Proceedings of CHI’ 98

Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems,

25-32.

Layne, K., Lee, J. 2001. Developing fully functional e-

government: a four stage model, Government

Information Quarterly, 18, 126-136.

Lee, S., Koubek, R. J., 2010. The effects of usability and

web design attributes on user preference for e-

commerce web sites, Computers in Industry, In Press,

Corrected Proof.

Muir, A., Oppenheim, C. 2002. National Information

policy developments worldwide in electronic

government, Journal of Information Science, 28(3),

173-186.

Nielsen, J., Molich, R., 1990. Heuristic evaluation of user

interface, Proceedings of the ACM CHI’92, 249-256.

Nielsen, J., 1994. Heuristic evaluation: usability inspection

methods, New York.

Nielsen, J. 2000. Deigning web usability: the practice of

simplicity, New Riders Publishing, Indiana, USA.

OECD 2003. OECD E-Government Studies: the e-

government imperative, OECD, Paris.

Reddick, C. G., 2005. Citizen interaction with e-

government: From the streets to servers?, Government

Information Quarterly, 22(1), 38-57.

Reddick, C. G. 2009. The adoption of centralized

customer service systems: a survey of local

governments, Government Information Quarterly,

26(1), 219-226.

Sauer, J., Sonderegger, A. 2009. The influence of

prototype fidelity and aesthetics of design in usability

tests: effects on users behaviour, subjective evaluation

and emotion, Applied Ergonomics, 40, 670-677.

Shareef, M. A., Kumar, V., Kumar, U., Dwivedi, Y. K.

2011. E-government adoption model (GAM): differing

service maturity levels, Government Information

Quarterly, 28, 17-35.

Sonderegger, A., Sauer, J., 2010. The influence of design

aesthetics in usability testing: effects on user

performance and perceived usability, Applied

Ergonomics, 41, 403-410.

Steyaert, J. C., 2004. Measuring the performance of

electronic government services, Information and

Management, 41(3), 369-375.

Tolbert, C., Mossberger, K., 2003. The effects of e-

government on trust and confidence in government,

Proceedings of the 2003 Annual National Conference

on Digital Government Research, Digital Government

Research Center, 1-7.

Virzi, R., 1992. Refining the test phase of usability

evaluation: how many subjects is enough? Human

factors, 24, 457-468.

Wang, L., Bretschneider, S., Gant, J., 2005 Evaluating

web-based e-government services with a citizen-

centric approach, Proceedings of the 38th Annual

Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences,

5, 129-139.

Yang, J. Q., Paul, S., 2005. e-Government application at

local level: issues and challenges: an empirical study,

International Journal of Electronic Government, 2(1),

56-76.

ADDRESSING E-GOVERNMENT WEBSITE USABILITY - A Users' Centred Evaluation

183