AN AGENT-BASED APPROACH TO CONSUMER´S LAW

DISPUTE RESOLUTION

Nuno Costa, Davide Carneiro, Paulo Novais

Department of Informatics, University of Minho, Braga, Portugal

Diovana Barbieri

Faculty of Law, Salamanca University, Salamanca, Spain

Francisco Andrade

Law School, University of Minho, Braga, Portugal

Keywords: Online Dispute Resolution, Multi-agent Systems, Consumer Law.

Abstract: Buying products online results in a new type of trade which the traditional legal systems are not ready to

deal with. Besides that, the increase in B2C relations led to a growing number of consumer claims and many

of these are not getting a satisfactory response. New approaches that do not include traditional litigation are

needed, having in consideration not only the slowness of the judicial system, but also the cost/beneficial

relation in legal procedures. This paper points out to an alternative way of solving these conflicts online,

using Information Technologies and Artificial Intelligence methodologies. The work here presented results

in a consumer advice system, which fastens and makes easier the conflict resolution process both for

consumers and for legal experts.

1 INTRODUCTION

B2C relations, on-line or off-line, are increasing.

Although these are, most of the times, simple

processes, there are often conflicts. To solve them

one may appeal to the courts. But, by the growing

amount of complaints, courts start piling the

processes, taking a long time to solve them, and

resulting in a highly negative cost/beneficial relation

in legal procedures. In order to have quicker and

more efficient decisions, one must start thinking in

alternative conflict resolution methods. Traditional

alternative methods may include negotiation,

mediation or arbitration and take place away from

courts, and now these may take place also on-line,

allowing faster and cheaper processes (Klaming,

2008).

2 ALTERNATIVES TO COURTS

2.1 Alternative Dispute Resolution

Several methods of ADR (Alternative Dispute

Resolution) may be considered, “from negotiation

and mediation to modified arbitration or modified

jury proceedings” (Goodman, 2003). In a

negotiation process the two parties meet each other

and try to obtain an agreement by conversation and

trade-offs, having in common the willing to

peacefully solve the conflict. It is a non binding

process, i.e. the parties are not obliged to accept the

outcome. In a mediation process the parties are

guided by a third neutral party, chosen by both, that

acts as an intermediate in the dispute resolution

process. As in negotiation, it is not a binding

process. At last, the arbitration process, which is the

most similar to litigation. In arbitration, a third,

independent party, hears the parties and, without

their intervention decrees an outcome. Although

103

Costa N., Carneiro D., Novais P., Barbieri D. and Andrade F. (2010).

AN AGENT-BASED APPROACH TO CONSUMER´S LAW DISPUTE RESOLUTION.

In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems - Artificial Intelligence and Decision Support Systems, pages

103-110

DOI: 10.5220/0002910701030110

Copyright

c

SciTePress

ADR methods represent an important step to keep

these processes away from courts, there is still the

need for a physical location in which the parties

meet, which may sometimes be impracticable, in the

non rare situations in which parties are from

different and geographically distant countries. A

new approach is therefore needed, one that uses the

advantages of already traditional ADR methods and,

at the same time, relies in the information

technologies for bringing the parties closer together,

even in a virtual way.

2.2 Online Dispute Resolution

Online Dispute Resolution (ODR) uses new

information technologies like instant messaging,

email, video-conference, forums, and others to put

parties into contact, allowing them to communicate

from virtually anywhere in the world.

The most basic settings of ODR systems include

legal knowledge based systems acting as simple

tools to provide legal advice, systems that try to put

the parties into contact and also “systems that (help)

settle disputes in an online environment” (De Vries

et al., 2005).

However, these rather basic systems can be

extended, namely with insights from the fields of

Artificial Intelligence, specifically agent-based

technologies and all the well known advantages that

they bring along. A platform incorporating such

concepts will no longer be a passive platform that

simply concerns about putting the parties into

contact (Chiti and Peruginelli, 2002). Instead, it will

start to be a dynamic platform that embodies the

fears and desires of the parties, accordingly adapts to

them, provides useful information on time, suggests

strategies and plans of action and estimates the

possible outcomes and their respective

consequences. It is no longer a mere tool that assists

the parties but one that has a proactive role on the

outcome of the process. This approach is clearly

close to the second generation ODR envisioned by

Chiti and Peruginelli as it addresses the three

characteristic enumerated in (Chiti and Peruginelli,

2002): (1) the aim of such platform does not end by

putting the parties into contact but consists in

proposing solutions for solving the disputes; (2) the

human intervention is reduced and (3) these systems

act as autonomous agents. The development of

Second Generation ODR, in which an ODR platform

might act “as an autonomous agent” (Chiti and

Peruginelli, 2002) is indeed an appealing way for

solving disputes.

ODR is therefore more than simply representing

facts and events; a software agent that performs

useful actions also needs to know the terms of the

dispute and the rights or wrongs of the parties (Chiti

and Peruginelli, 2002). Thus, software agents have

to understand law and/or and processes of legal

reasoning and their eventual legal responsibility

(Brazier et al., 2002).

This kind of ODR environment thus goes much

further than just transposing ADR ideas into virtual

environments; it should actually be “guided by

judicial reasoning”, getting disputants “to arrive at

outcomes in line with those a judge would reach”

(Muecke et al., 2008). Although there are well

known difficulties to overcome at this level, the use

of software agents as decision support systems

points out to the usefulness of following this path.

3 UMCourt: THE CONSUMER

LAW CASE STUDY

UMCourt is being developed at University of Minho

in the context of the TIARAC project (Telematics

and Artificial Intelligence in Alternative Conflict

Resolution). The main objective of this project is to

analyze the role that AI techniques, and more

particularly agent-based techniques, can play in the

domain of Online Dispute Resolution, with the aim

of making it a faster, simpler and richer process for

the parties. In that sense, UMCourt results in an

architecture upon which ODR-oriented services may

be implemented, using as support the tools being

developed in the ambit of this project. These tools

include a growing database of past legal cases that

can be retrieved and analyzed, a well defined

structure for the representation of these cases and the

extraction of information, a well defined formal

model of the dispute resolution process organized

into phases, among others.

The tools mentioned are being applied in case

studies in the most different legal domains, ranging

from divorce cases to labor law. In this paper, we

present the work done to develop an instance of

UMCourt to the specific domain of consumer's law.

As we will see ahead, the distributed and expansible

nature of our agent-based architecture is the key

factor for being able of developing these extensions,

taking as a common starting point the core agents

developed.

In a few words, consumer's law process goes as

follows. The first party, usually the buyer of the

product or service, starts the complaint by filling an

online form. The data gathered will then be object of

analysis by a group of agents that configure an

Intelligent System that has a representation of the

legal domain being addressed and is able to issue an

ICEIS 2010 - 12th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

104

outcome. At the same time, other agents that make

up the core of the platform analyze past similar cases

and respective outcomes, that are presented to the

user in the form of possible outcomes, so that the

user can have a more intuitive picture of what may

happen during the process and therefore fight for

better outcomes.

At the end, a Human mediator will verify the

proposed solution. He can agree with it or he can

change it. In both cases, the agents learn with the

human expert. If the expert agrees with the outcome

proposed, the agents strengthen the validity of the

cases used, otherwise the opposite takes place. This

means that the system is able to learn with both

correct and incorrect decisions: failure driven

learning (Leake, 1996). The developed system is not

to be assumed as a fully automatic system whose

decisions are binding but as a decision support

system which is aimed at decreasing the human

intervention, allowing a better management of the

time spent with each case and, nevertheless, still

giving the Human the decision making role. The

main objective is therefore to create an autonomous

system that, based on previous cases and respective

solutions, is able to suggest outcomes for new cases.

Among the different law domains that could be

object of our work we choose consumer's law. This

choice was made after noticing that consumer claims

in Portugal, particularly those related to acquisition

of goods or services, are not getting, most times, the

solutions decreed in the Portuguese law,

undoubtedly due to an unfair access to justice, high

costs of judicial litigation versus value of the

product/service and the slowness of the judicial

procedure. All this generally leads the consumer to

give up on the attempt to solve the conflict with the

vendor/supplier.

Having all this into consideration, we believe

that an agent-based ODR approach, with the

characteristics briefly depicted above, is the path to

achieve a better, faster and fairer access to justice.

3.1 Consumer Law

As mentioned above, the legal domain of this

extension to UMCourt is the Portuguese consumer's

law. Because this domain is a quite wide one, we

restricted it to the problematic of buy and sell of

consumer goods and respective warranties contracts.

In this field there is a growing amount of conflicts

arising between consumers and sellers / providers. In

this context, the approach was directed to the

modeling of concrete solutions for the conflicts

arising from the supply of defective goods

(embodied mobiles or real estate).

We also thought relevant to consider financial

services as well as the cases in which there are

damages arising out of defective products, although

this is yet work in progress.

Regarding the boundaries that were established

for this extension of UMCourt, we have tried to

model the solutions for conflicts as they are depicted

in Decree of Law (DL) 67/2003 as published by DL

84/2008 (Portuguese laws).

Based upon the legal concepts of consumer,

supplier, consumer good and the concluded legal

business, established on the above referred DL and

on the Law 24/1996 (Portuguese law), we developed

a logical conduct of the prototype, having in view

the concrete resolution of the claims presented by

the buyer. In this sense, we considered the literal

analysis of the law, as well as the current and most

followed opinions in both Doctrine and national

Jurisprudence.

During the development and assessment of the

platform, we realized that the prototype can be

useful in cases when the consumer (PHISICAL

PERSON) (Almeida T., 2001) is acquiring the good

for domestic/private use (Almeida, C. F., 2005), or is

a third acquirer of the good (Law 24/1996, article

2nd nr.1, and DL 67/2003, article 1st B, a) and 4th

nr. 6). Besides these cases, it is also usefully applied

in situations in which the consumer has celebrated a

legal contract of acquisition, buy and sell within

taskwork agreement, or renting of embodied mobile

good or real estate (DL 67/2003, article 1st A and

1st B, b)).

Still, contracting must take place with a supplier

acting within the range of his professional activities,

being this one the producer of the good himself, an

importer in the European Union, an apparent

producer, a representative of the producer or even a

seller (Law 24/1996, article 2nd nr. 1 and DL

67/2003, art. 1st B, c), d) and e)). At last, the defect

must have been claimed within the delay of warranty

(DL 67/2003, articles 5 and 9), and the delay in

which the consumer is legally entitled to claim his

rights towards the supplier has as well to be

respected (DL 67/2003, article 5 A).

Once the legal requests are fulfilled, the solutions

available to the consumer will be: repairing of the

good (DL 67/2003, articles 4th and 6th);

replacement of the good (DL 67/2003 articles 4th

and 6th); reduction of price (DL 67/2003 article

4th); resolution of the contract (DL 67/2003, article

4th) or statement that there are no rights to be

claimed by the consumer (DL 67/2003, art. 2nd, nrs.

3 and 4, arts. 5, 5A and 6).

AN AGENT-BASED APPROACH TO CONSUMER´S LAW DISPUTE RESOLUTION

105

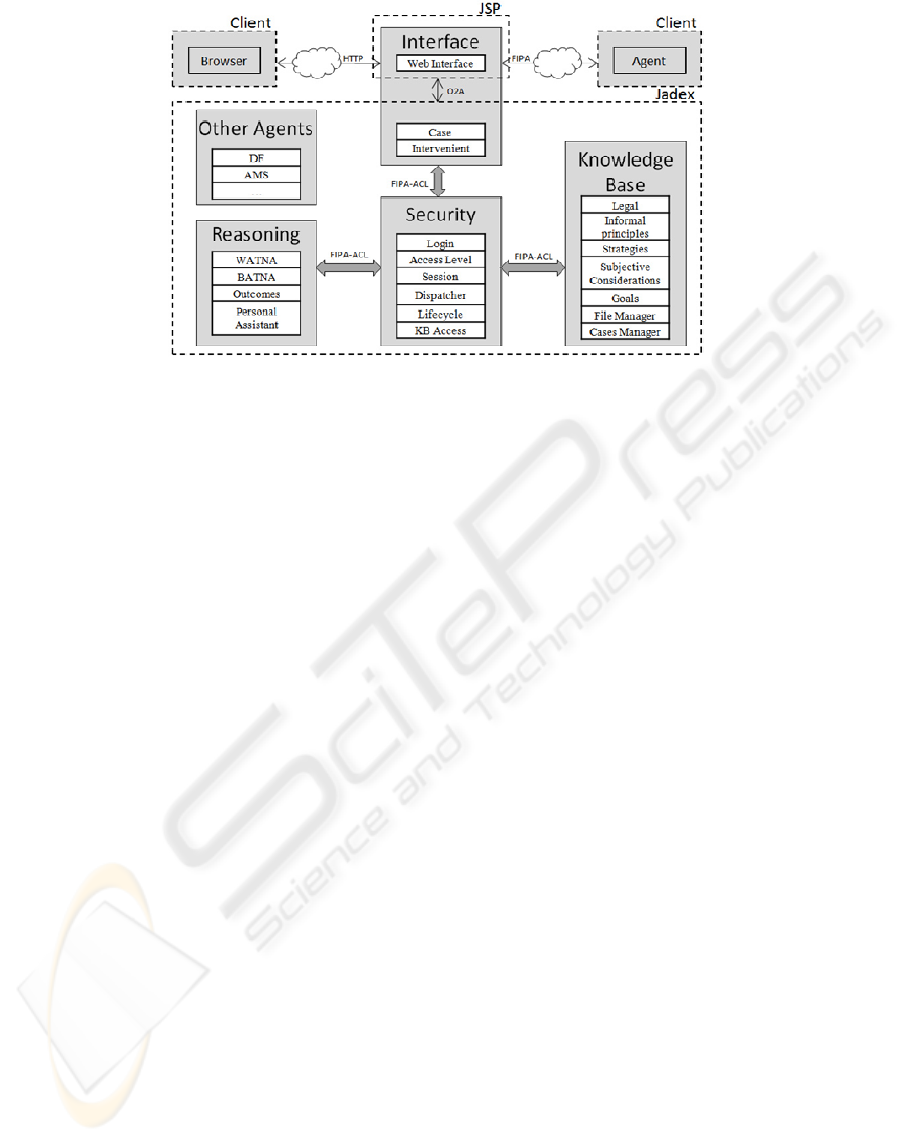

Figure 1: A simplified version of the system architecture.

These decrees have been modeled in the form of

logic predicates and are part of the knowledge of the

software agents, which use these predicates in order

to make and justify their decisions.

3.2 Architecture

As stated before, the architecture of UMCourt is an

agent-based one. In Figure 1 a view of the core

agents that build the backbone of the architecture is

shown. This backbone has as the most notable

services the ability to compute the Best and Worst

Alternative to a Negotiated Agreement, BATNA and

WATNA, respectively (Notini, 2009) and the

capacity to present solutions based in the

observation of previous cases and their respective

outcomes (Andrade et al, 2009)

The interaction of the user starts by registering in

the platform and consequent authentication. Through

the intuitive dynamic interfaces, the user inputs the

requested needed information. After submitting the

form, the data is immediately available to the agents

that store it in appropriate well defined XML files.

This data can later be used by the agents for the most

different tasks: showing it to the user in an intuitive

way, automatic generation of legal documents by

means of XSL Transformations, generation of

possible outcomes, creation of new cases, among

others. Alternatively, external agents may interact

directly with the platform by using messages that

respect the standard defined.

Table 1 shows the four high-level agents and some

of their most important roles in the system. To

develop the agents we are following the evolutionary

development methodology proposed by (Jennings,

2001). We therefore define the high level agents and

respective high level roles and interactively break

down the agents into more simple ones with more

specific roles. The platform, without the extensions,

is at this moment constituted by 20 simpler agents.

To the agents that make part of the extension we will

call from now on extension agents. Among these

phase tests can be conducted to access the behaviour

of the overall system. This means that the

advantages of choosing an agent-based architecture

are present throughout all the development process,

allowing us to easily remove, add or replace agents.

It also makes it easy to later on add new

functionalities to the platform, by simply adding

new agents and their corresponding services, without

interfering with the already stable services present.

This modular nature of the architecture also

increases code reuse, making it easier to develop

higher level services through the compositionality of

smaller ones. The expansibility of the architecture is

also increased with the possibility to interact with

remote agent platforms as well as to develop

extensions to the architecture, like the one presented

in this paper. We also make use of the considerable

amount of open standards and technologies that are

nowadays available for the development of agent-

based architectures that significantly ease the

development, namely FIPA standards and platforms

such as Jade or Jadex.

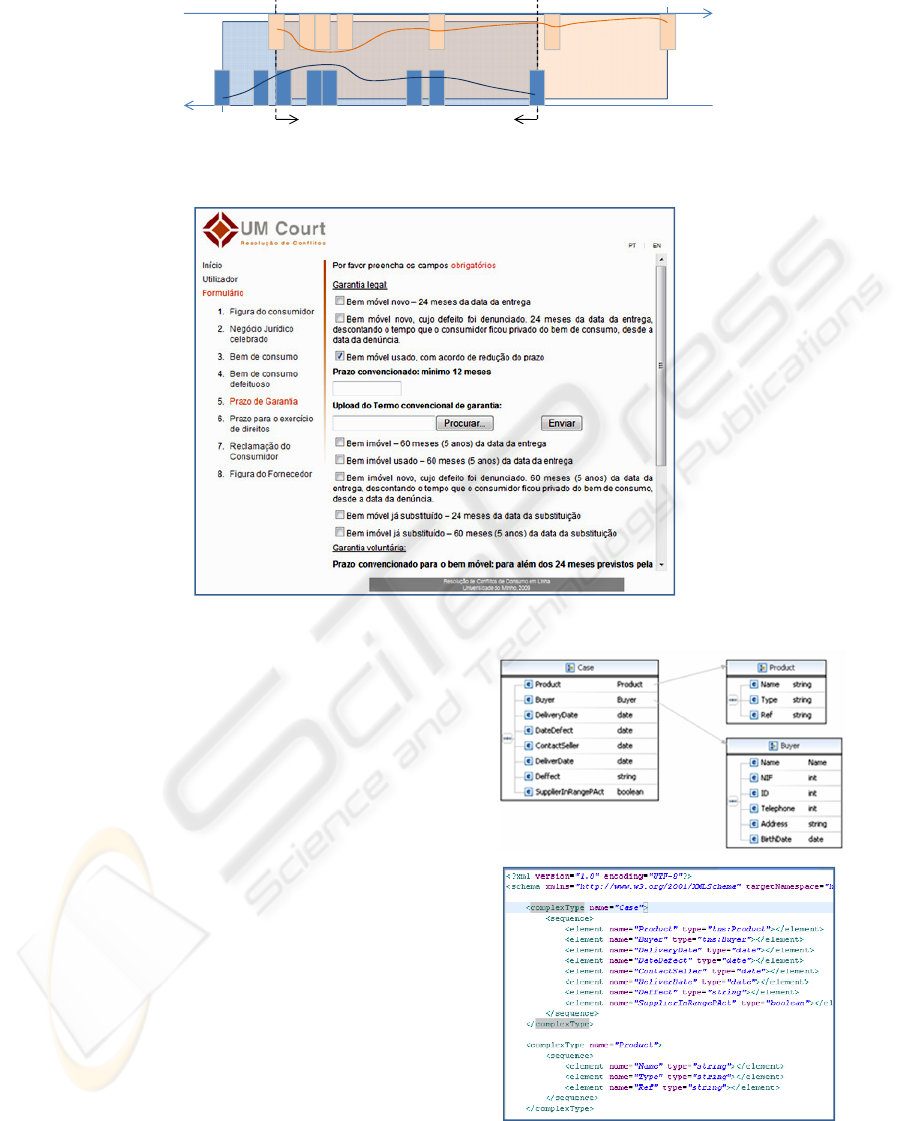

3.3 Data Flow in the System

All the modules that integrate the system meet the

current legislation on consumer's law. When the user

fills the form to start a complaint, he indicates the

type of good acquired, the date of delivery and the

date of defective good denunciation, stipulating also

the date when the good was delivered to repair

ICEIS 2010 - 12th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

106

Table 1: The four high-level agents and their main roles.

High-level Agent Description Main Roles

Security

This agent is responsible for

dealing with all the security

issues of the system

Establish secure sessions with users

Access levels and control

Control the interactions with the knowledge base

Control the lifecycle of the remaining agents

Knowledge Base

This agent provides methods for

interacting with the knowledge

stored in the system

Read information from the KB

Store new information in the KB

Support the management of files within the system

Reasoning

This agent embodies the

intelligent mechanisms of the

system

Compute the BATNA and WATNA values

Compute the most significant outcomes and their

respective likeliness

Proactively provide useful information based on the

phase of the dispute resolution process

Interface

This agent is responsible for

establishing the interface between

the system and the user in a

intuitive fashion

Define a intuitive representation of the information of

each process

Provide an intuitive interface for the interaction of the

user with the system

Provide simple and easy access to important

information (e.g. laws) according to the process domain

and phase

and/or substitution. He can also indicate the period

of extrajudicial conflict resolution attempt, if

necessary. To justify these dates the user has to

present evidence, in general the issued invoices, by

uploading them in digital format. Concerning the

defective good, he must indicate its specification and

the probable defect causes. At last, he has to identify

the supplier type as being a producer or a seller.

After filled, the form is submitted. Figure 3 shows a

screenshot of the online form.

When the form is submitted, a group of actions is

triggered with the objective of storing the

information in appropriate well defined structures.

As mentioned before, these structures are XML files

that are validated against XML Schemas in order to

maintain the integrity of the data. All these files are

automatically created by the software agents when

the data is filled. The extension agent responsible for

performing these operations is the agent Cases.

After all the important information is filled in

and when a solution is requested, these and other

agents interact. Agents BATNA and WATNA are

started after all the information is provided by the

parties through the interface (Figure 3). These agents

then interact with the extension agents Cases and

Laws in order to retrieve the significant information

of the case and the necessary laws to determine the

best and worst scenarios that could occur if the

negotiation failed and litigation was necessary.

Agent Outcomes interacts with extension agent

Cases in order to request all the necessary

information to be able to retrieve the most similar

cases.

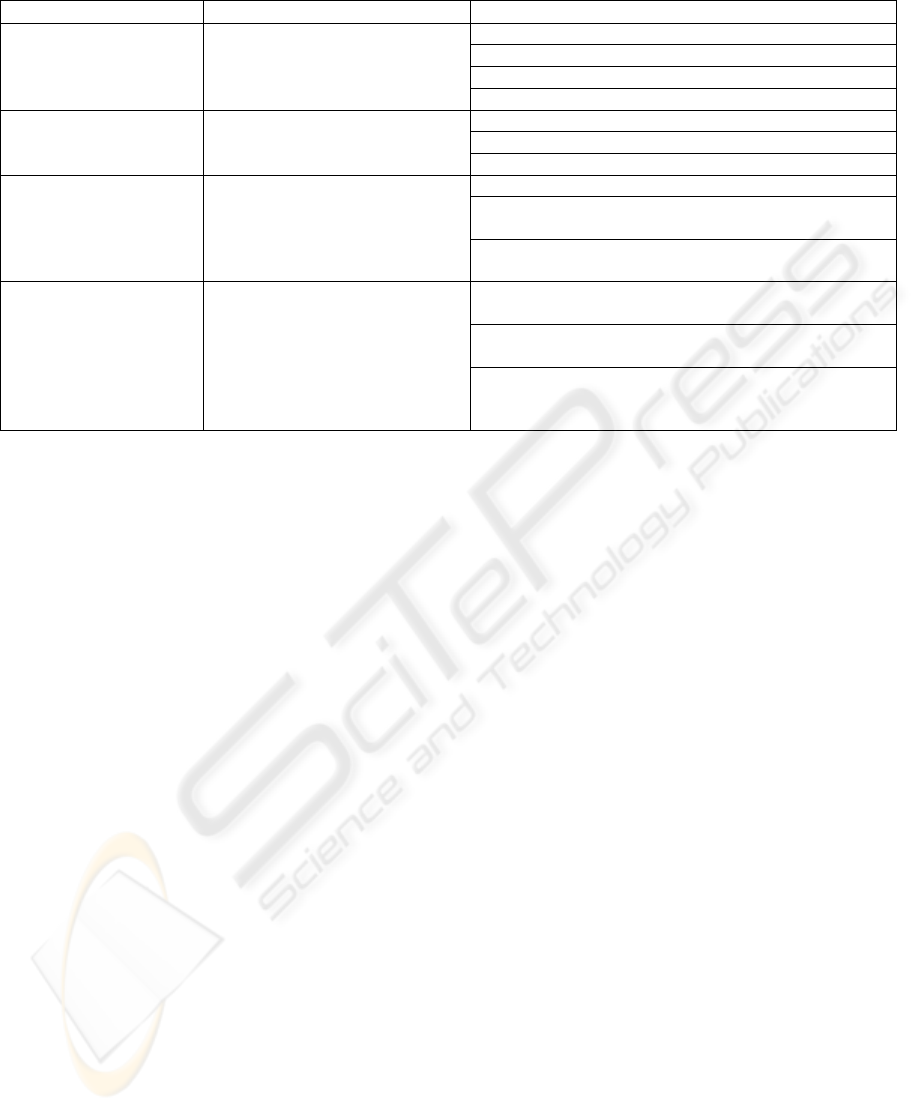

All this information (WATNA, BATNA and

possible outcomes) is then presented to the user in a

graphical fashion so that it may be more intuitively

perceived (Figure 2). In that sense, the likeliness is

represented by the colored curves which denote the

area in which the cases are more likely to occur. A

higher likeliness is denoted by a line that is more

distant from the axis. To determine this likeliness,

the amount of cases in the region is used, as well as

the type of case (e.g., decisions of higher or lower

court) and even if there are groups of cases instead

of single cases, as sometimes highly similar cases

are grouped to increase the efficiency. The graphical

representation also shows the range of possible

outcomes for each of the parties in the form of the

two big colored rectangles and the result of its

intersection, the ZOPA – Zone of Potential

Agreement (Lewicki, 1999), another very important

concept that allows the parties to see between which

limits is an agreement possible. The picture also

shows each case and its position in the ordered axis

of increasing satisfaction, in the shape of the smaller

rectangles.

Looking at this kind of representation of

information, the parties are able to see that the cases

are more likely to occur for each party when they are

in the area where the colored lines are further away

from the axis of that party. Therefore, the probable

outcome of the dispute will probably be near the

area where the two lines are closer.

At this point, the user is in a better position to make

a decision as he possesses more information, namely

important past similar cases that have occurred in

the past. In this position the user may

AN AGENT-BASED APPROACH TO CONSUMER´S LAW DISPUTE RESOLUTION

107

Figure 2: The graphical representation of the possible outcomes for each party.

Figure 3: Online form.

engage in conversations with the other party in an

attempt to negotiate an outcome, may request an

outcome or may advance to litigation, if the

WATNA is believed to be better than what could be

reached through litigation.

If the user decides to ask the platform for a

possible solution, the Reasoning extension agent will

contact the extension agents Cases and Laws in

order to get the information of the case and the laws

that should be applied and will issue an outcome.

The neutral, when analyzing the outcome

suggested, may also interact with these agents, for

consulting a specific law or aspect of the case. He

analyses all this information, and decides to accept

or not to accept the decision of the system. After the

solution is verified, it is validated and presented to

the user.

3.4 Example and Results

To better expose these processes, let us use as an

example a fictitious case (Figure 5): a physical

person that acquires an embodied mobile good for

domestic/private use. The celebrated legal contract is

Figure 4: Excerpts and tables from XML Schemas for

some case information.

BATNA WATNA

WATNA BATNA

P1

Increasing

Satisfaction

P2

Increasing

Satisfaction

ZOPA

ICEIS 2010 - 12th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

108

Figure 5: Extract from an example case.

of the type buy and sell. The date of good delivery is

October 22

nd

, 2009. The date at which the consumer

found the defect in the good occurred at October

26

th

, 2009 but the good was delivered to repair

and/or substitution on October 30

th

, 2009. There was

no extrajudicial conflict resolution attempt. As

evidence, the user uploaded all invoices relative to

the dates mentioned. Concerning the defect that

originated the complaint, the user mentioned that the

good did not meet the description that was made to

him when it was bought. In this case, the supplier

acts within the range of his professional activities

and he is the producer of the good.

When a solution is requested, the system

proceeds to the case analysis and reaches a solution.

The good is under the warranty delay: 11 days,

calculated through the difference between the date of

good delivery and the actual date

The limit of two months between the date of the

defect detection has been respected: 7 days,

calculated by the difference between the date of

defect finding and the actual date. Two years have

not passed since the date of denunciation: 2 days,

calculated by the difference between the date of

denunciation and the actual date, deducting the delay

which user was deprived of the good because of

repair/substitution (since no date of good delivery

after repair and/or substitution is declared, the

default is the actual date). The period of extrajudicial

conflict resolution attempt is also deductable, but in

this case it doesn’t occur. As the good was delivered

for repair and/or substitution, the supplier has two

choices: either make the good repair in 30 days (at

the maximum) without great inconvenience, and at

no cost (travel expenses, man power and material) to

the consumer; or make the good replacement by

another equivalent.

This rather yet simplistic approach is very useful

as a first step on the automation of these processes.

The case shown here is one of the simplest ones but

the operations performed significantly ease the work

of the law expert, allowing him to worry about

higher level tasks while simpler tasks, that can be

automated, are performed by autonomous agents.

4 CONCLUSIONS

In the context of consumer's law, only some aspects

have been modeled, still remaining for future work:

a) the situations covered by the Civil Code, when

DL 67/2003 is not to be applied; b) the cases

considered in DL 383/89 of damages arising from

defective products; and c) the issues of financial

services, namely concerning consumer’s credit. The

work developed until now, however, is already

enough to assist law experts, enhancing the

efficiency of their work.

The next steps are in the sense of further

improvements of the agents while at the same time

continuing the extension to other aspects of

consumer's law that have not yet been addressed in

this work. Specifically, we will adapt a Case-based

Reasoning Model that has already been successfully

applied in previous work in order to estimate the

outcomes of each case based on past stored cases.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The work described in this paper is included in

TIARAC - Telematics and Artificial Intelligence in

Alternative Conflict Resolution Project

(PTDC/JUR/71354/2006), which is a research

project supported by FCT (Science & Technology

Foundation), Portugal.

REFERENCES

Almeida, C. F., 2005. Direito do Consumo. Almedina.

Coimbra (in portuguese).

Almeida T., 2001. Lei de defesa do consumidor anotada,

Instituto do consumidor, Lisboa(in portuguese).

Andrade F., Novais P., Carneiro D., Zeleznikow J., Neves

J., 2009. Using BATNAs and WATNAs in Online

Dispute Resolution, proceedings of the JURISIN 2009

- Third International Workshop on Juris-informatics,

Tokyo, Japan, ISBN 4-915905-38-1, pp 15-26.

Bellifemine, F., Caire, G., Greenwood, D., 2007.

Developing Multi-Agent Systems with JADE, John

Wiley & Sons, Ltd. West Sussex, England.

AN AGENT-BASED APPROACH TO CONSUMER´S LAW DISPUTE RESOLUTION

109

Chiti, G., Peruginelli, G.: Artificial intelligence in

alternative dispute resolution. Proceedings of LEA, pp.

97–104. (2002)

De Vries BR., Leenes, R., Zeleznikow, J., Fundamentals

of providing negotiation support online: the need for

developping BATNAs. Proceedings of the Second

International ODR Workshop, Tilburg, Wolf Legal

Publishers (2005) 59-67.

Goodman, J.W., The pros and cons of online dispute

resolution: an assessment of cyber-mediation websites,

in Duke Law and Technology Review (2003).

Jennings, N., Faratin, P., Lomuscio, A., Parsons, S.,

Wooldridge, M., & Sierra, C.: Automated Negotiation:

Prospects, Methods and Challenges. Group Decision

and Negotiation, 10(2), 199-215. (2001)

Klamig, L., Van Veenen, J., Leenes, R., I want the

opposite of what you want: summary of a study on the

reduction of fixed-pie perceptions in online

negotiations. “Expanding the horizons of ODR”,

Proceedings of the 5th International Workshop on

Online Dispute Resolution (ODR Workshop’08),

Firenze, Italy (2008) 84-94.

Leake, D. B. (1996). Case-Based Reasoning: Experiences,

Lessons, and Future Directions. AAAI Press.

Lewicki, R., Saunders, D., Minton, J., Zone of Potential

Agreement, In Negotiation, 3rd Edition. Burr Ridge,

IL: Irwin-McGraw Hill (1999).

Muecke, N., Stranieri, A., Miller, C., The integration of

online dispute resolution and decision support

systems. Expanding the horizons of ODR, Proceedings

of the 5th International Workshop on Online Dispute

Resolution (ODR Workshop’08), Firenze, Italy (2008)

62-72.

Notini, J.: Effective Alternatives Analysis In Mediation:

“BATNA/WATNA” Analysis Demystified,

(http://www.mediate.com/articles/notini1.cfm), 2005.

Last accessed on November, 2009.

Silva, J. C., 2006. Venda de bens de consumo. DL n.º

67/2003, de 8 de Abril. Directiva n.º 1999/44/CE.

Comentário. Almedina. Coimbra (in portuguese).

Silva, J. C., 2006. Compra e Venda de Coisas Defeituosas.

Conformidade e Segurança. Almedina. Coimbra (in

portuguese).

ICEIS 2010 - 12th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

110