Organizational Knowledge and Change: The Role of

Transformational HRIS

Huub Ruel

1

and Rodrigo Magalhaes

2,3

1

University of Twente, Enschede, The Netherlands

2

Kuwait-Maastricht Business School, Dasma, Kuwait

3

Organizational Engineering Center, INESC Inovação, Lisbon, Portugal

Abstract. Research on HRIS has uncovered different types of HR systems,

namely operational, relational and transformational. Each type of HRIS

addresses a particular organizational problem and must be researched with a

particular type of research design. In this paper the issue of transformational

HRIS is addressed with the emphasis being placed on the need to associate this

type of system with the broader concerns of organizational knowledge and its

impact on the competitiveness of business. Such a link is achieved through a

conceptual tools named the Organizational Knowledge Cycle and illustrated by

the re-visitation of the case of Dow Chemicals’ People Success System (PSS) in

the Benelux [7].

1 Introduction

The global spread of information technologies in the last 30 years has facilitated the

establishment of knowledge (individual and organizational) as the driving force of the

economy. Thus, in the early 21

st

century, we can safely talk of organizational

knowledge as a competitive market pressure as a major cause/consequence of the

organizational integration of information technology [1]. Enabled by IT applications,

human networking and organizational communication have become key ingredients in

the overall improvement of the effectiveness of organizational processes which, in

turn, provides a major contribution to the creation and accumulation of knowledge in

the organization.

Organizational knowledge is credited now-a-days as the key variable in sustainable

competitive growth [2] [3] [4] [5] [6]. And as more knowledge is created and

accumulated within and across organizations with the contribution of IT applications,

the greater the demands from the market for more infusion and more diffusion of such

applications. There exits therefore a circular loop of cause and effect between the

adoption of IS/IT and the creation of organizational knowledge.

In this paper we explore this loop by focussing on one type of IT application -

Human Resources Information Systems (HRIS). HRIS, in turn, are made up of

various types – operational, relational and transformational. It is our contention that

transformational HRIS are better understood in the context of an organizational

knowledge management framework. We put forward the organizational knowledge

cycle as a conceptual tool to analyse the impact of transformational HRIS on the state

Ruel H. and Magalhaes R. (2008).

Organizational Knowledge and Change: The Role of Transformational HRIS.

In Proceedings of the 2nd International Workshop on Human Resource Information Systems, pages 111-123

DOI: 10.5220/0001744001110123

Copyright

c

SciTePress

of organizational knowledge in the organization, thereby allowing conclusions to be

taken not only about this type of HRIS but also about the process of organizational

transformation itself. In order to validate our proposition, we re-visit an empirical

case study by [7] of a transformational HRIS - Dow Chemical in the Benelux. Our

aim is not to re-interpret the case but simply to show the benefits of the organizational

knowledge cycle as a methodological tool for establishing the links between HRIS

and organizational transformation.

2 Perspectives on Organizational Knowledge

Nonaka and Tekeuchi [8] have put forward a well known theoretical framework for

the creation of organizational knowledge where the various elements of knowledge

creation are identified and interrelated in a dynamic whole. The framework

incorporates two major dimensions, one epistemological and one ontological. The

epistemological dimension contains the theory’s key proposal, i.e. that the interactive

processes of knowledge conversion, between tacit and explicit knowledge, lies at the

heart of knowledge creation [8]. There are four possible modes of knowledge

conversion, at the epistemological level: from tacit to tacit (socialization); from tacit

to explicit (externalization); from explicit to tacit (internalization); and from explicit

to explicit (combination). The ontological dimension considers four different levels of

knowledge creation: individual, group, organization and inter-organization. Along the

ontological axis, the knowledge creation movement starts with the individual’s tacit

knowledge, is amplified through the four modes of knowledge conversion and is

finally crystallized at higher ontological levels (organizational or inter-

organizational).

The theoretical framework put forward by Nonaka and Tekeuchi [8] is compatible

with Orliskowski’s [9] epistemological notion of knowing-in-practice, i.e. “the mutual

constitution of knowing and practice” (p. 251). Supported by the Gidden´s [10]

structuration theory and by Maturana and Varela’s [11] concept of autopoiesis,

Orliskowski explains that knowledge lies essentially in the practice. Knowledge is not

something which is inscribed in our thoughts or our brains but knowledge is what

makes practice come to life. Knowing-in-practice is equivalent to Gidden’s concept of

knowledgeability or the inherent ability of human beings to “go on with the routines

of social life” [10, p. 4]. Hence, it is neither “out there”, incorporated in external

systems or “in here”, inscribed in the human brain, but is something that exists in

people’s ongoing engagement in social practices. Competence or skillful practice is,

therefore, is not something that can be presumed independent of practice.

Besides the epistemological and ontological dimensions, knowledge creation can

also be approached from a pragmatic perspective. Pragmatic knowledge is that which

is intended to reach objectives within a limited time period. The objective might be,

for example, to improve the levels of an organization’s efficiency, effectives and

competitivity. In accordance with this perspective Holzner and Marx [cited in 12]

proposes the formulation of society’s knowledge system as being a five-step process

of construction, organization, storage, distribution and application of knowledge. This

perspective is consistent with both Nonaka and Takeuchi’s [8] SEIC framework for

112

the formation of organizational knowledge and with Orliskowski’s [9]

epistemological notion of knowing-in-practice. On the other hand, each of the steps of

the organizational knowledge cycle has been approached by a variety of authors from

the organizational learning and the knowledge management literatures. An overview

of some of the most representative authors whose writings support each of the steps of

the cycle is presented in Table 1. It is also important to point out that such a cycle is

not linear in the sense that it does not have start or end points. Given that individual

knowledge pre-exists the organization and that it is difficult to determine exactly

when individual knowledge becomes organizational, the cycle can start at any point.

Regarding the end point, some knowledge will be applied and utilized by the

organization, but some might just remained shared or stored without any utilization.

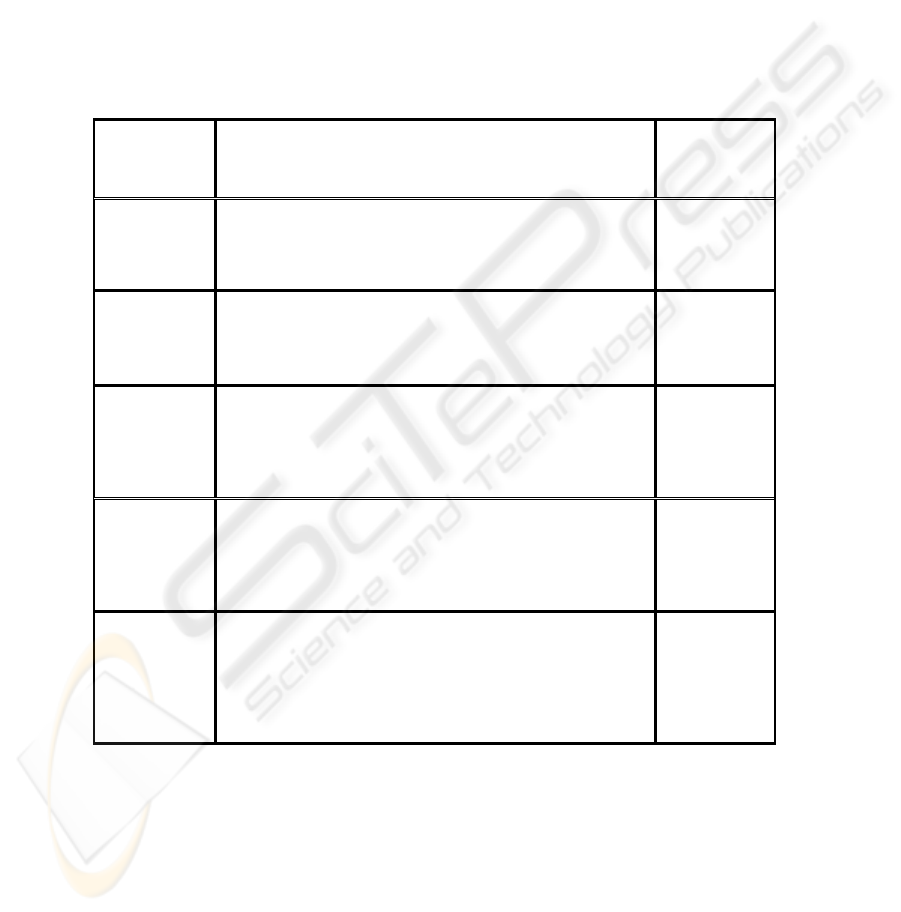

Table 1. The Organizational Knowledge Cycle.

KNOWLEDGE

PROCESS

DESCRIPTION IN AN ORGANIZATIONAL

SETTING

SUPPORT

FROM THE

LITERATURE

Formation or

Construction of

Knowledge

Purposeful action towards reaching objectives (pragmatic/ strategic

view). Searching, identifying, locating, validating and accessing

knowledge and information relevant to the organization and its

objectives

[8] [13] [14] [15]

Organization of

Knowledge

Integration into known categories. Organizational structures.

Process architectures. Information and work flows. Organizing,

codifying, appropriating, absorbing and incorporating knowledge

and information within the bounds of the organization

[16] [17]

Storage or

Retention of

Knowledge

Recording in oral and written media. Institutions and people

themselves as means of retaining knowledge. IT as the means of

storing and “textualizing” information. Aquiring and managing the

resources which contribute to the creation and accumulation of the

organization’s stock of knowledge and information.

[18] [19] [20]

[21] [22]

Distribution,

Transfer or

Sharing of

Knowledge

Channeling of knowledge to where it is needed. Communication.

Dialogue. Facilitation (culture and climate) and Inhibition

(organizational politics) factors. Leadership styles. Managing the

communication, the diffusion and the sharing of knowledge in the

organization.

[23] [24] [25]

[26] [27]

Aplication, Use or

Re-Creation of

Knowledge

Construction presuposes Application (pragmatic view). Excelence

of output. Improvements in performance. Re-creation of

knowledge. Innovation. Enabling, evaluating, rewarding and

institutionalizing (i.e. cristalizing) organizational results rated as

highly performant, excellent or innovative, achieved intra or inter-

organizationally

[28] [29] [30]

[31]

The knowledge life cycle and its five processes are a theoretical construct

representing actual needs for survival and growth of any organization. The expression

“process” is used to mean that knowledge is the result of actual practices, embedded

in the social and physical structure of the organization. Given the dynamic character

of knowledge, the cycle is not intended to mean a sequential type of behaviour. On

the contrary, the cycle’s processes interact randomly and simultaneously. The process

113

of Use/Re-creation is the final aim of the cycle and serves as the measure for the

effectiveness of knowledge management activities in the organization. Processes, by

definition, cut across the whole organization and work within contexts. There are

many contexts within the organization where it is necessary to act in order to make it

more responsive to the requirements of knowledge creation. Thus, when analysing a

knowledge creation cycle it is necessary to spell out the context(s) of interest.

3 Organizational Knowledge and HRIS

The effects of implementing information technology artefacts cannot be pinned down

to one or two areas in the organization, but are much more pervasive and continuous.

Implementation should not be seen as a “one-off” event, which is finished when the

information systems development cycle is complete. We see any form of IT

implementation as a process more akin to organizational learning and change then to a

single step in the methodological frameworks popularized by information systems

development methodologies. The key issue regarding IT implementation in

organization is organizational change which, in turn, is a holistic, complex and non-

linear process[32]. An organizational change perspective on the application of IT in

organizations affords us the necessary linkage between the perspective on pragmatic

knowledge outlined above and HRIS.

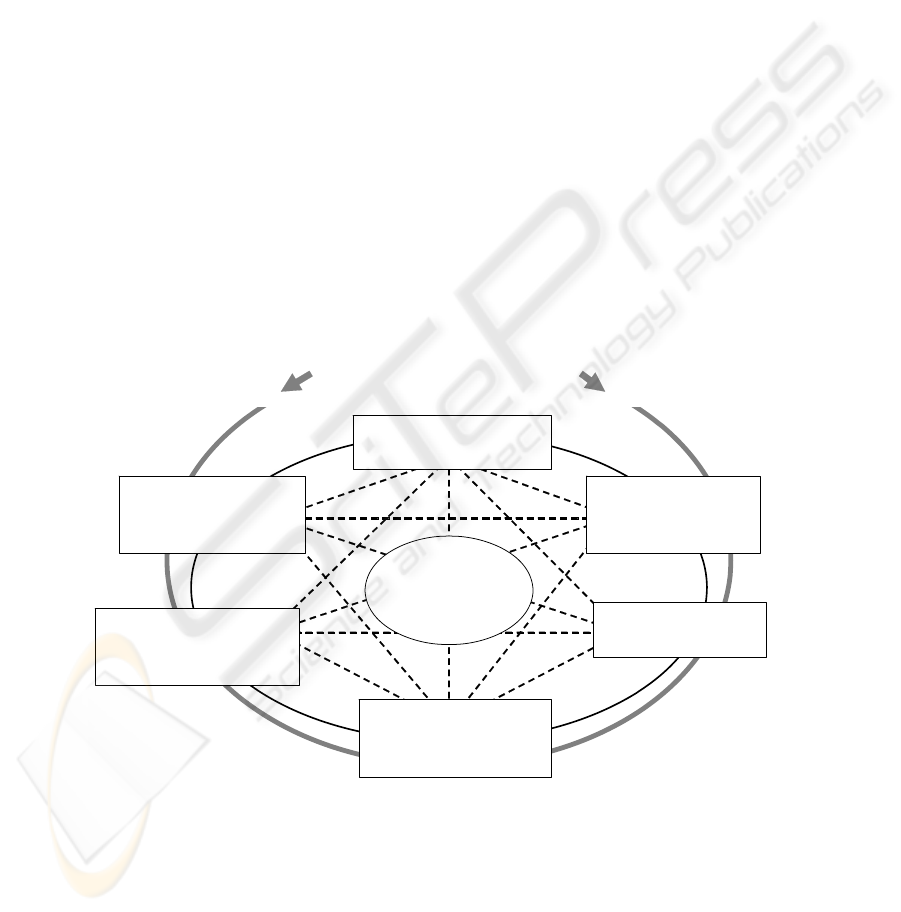

Fig.1.

In Figure 1 a diagram representing the impact of HRIS on the organizational

knowledge cycle is presented. It depicts the relationship among the five steps of the

Designing

Outcomes

Knowledge creation

contexts

Formation or

Construction of

Knowledge

Aplication, Use or

Re-Creation of

Knowledge

Storage or

Retention of

Knowledge

Distribution,

Transfer or Sharing

of Knowledge

Organization of

Knowledge

HRIS’s role in organizational transformation

114

cycle and the knowledge creation contexts. The interaction of the six dimensions

gives rise to changes in organizational design, with design being the ultimate

destination of organizational transformation. This model will be used to re-visit the

empirical case study of Dow Chemical in the Benelux [7].

3.1 Types of HRIS

HRIS is not a specific stage in the development of HRM, but a choice for an approach

to HRM. Wright and Dyer [33] distinguish three areas of HRM where organizations

can choose to ‘offer’ HR services face-to-face or through an electronic means:

transactional HRM, traditional HRM, and transformational HRM. Lepak and Snell

[34] make a similar distinction, namely operational HRM, relational HRM and

transformational HRM. In this paper we address only the transformational dimension

of HRM.

The first area, operational HRM, concerns the basic HR activities in the

administrative area. One could think of salary administration (payroll) and personnel

data administration. The second area, relational HRM, concerns more advanced HRM

activities. The emphasis here is not on administering, but on HR tools that support

basic business processes such as recruiting and the selection of new personnel,

training, performance management and appraisal, and rewards. Transformational

HRM, the third area concerns HRM activities with a strategic character. Here we are

talking about activities regarding organizational change processes, strategic re-

orientation, strategic competence management, and strategic knowledge management.

The areas mentioned could also be considered as types of HRM that can be

observed in practice. In some organizations, the HRM emphasis is on administration

and registration, in others on the application of operational HRM instruments, and in a

third group the HRM stress is on its strategic role. Within all the types of HRM,

choices can be made in terms of which HRM activities will be offered face-to-face,

and which will be offered through web-based HR (e-enabled). This question, for the

operational type of HRM, provides the choice between asking employees to keep their

own personal data up-to-date through an HR website or to have an administrative

force in place to do this.

For relational HRM there is the choice between supporting recruitment and

selection through a web-based application or using a paper-based approach (through

advertisements, paper-based application forms and letters etc.). Finally, in terms of

transformational HRM, it is possible to create a change-ready workforce through an

integrated set of web-based tools that enables the workforce to develop in line with

the company’s strategic choices or to have paper-based materials.

In cases where an organization consciously and in a focused way chooses to put in

place web technology for HRM purposes, based upon the idea that management and

employees should play an active role in carrying out HR work, we can speak of e-

HRM. With this line of reasoning, three types of HRIS can be distinguished:

Operational HRIS, Relational HRIS, and Transformational HRIS.

115

4 The Empirical Case: Dow Chemicals

The Dow Chemical Company is one of the largest chemical companies in the world.

This US-based company (Midland, Michigan) is now active in 33 countries around

the globe. In 2001, Dow completed an important milestone, namely the merger with

Union Carbide, which strengthens Dow’s position as a global chemical company.

Until de mid-1990s Dow had been a country-oriented company, with fairly

autonomous sites around the world only loosely coupled with Dow sites in other

countries. In the last decade this changed and Dow aims to become a global company.

Dow’s organizational structure is flat (a maximum of six layers) and based upon

worldwide-organized businesses. This provides employees with a high level of

independence and accountability, working in self-managing teams, including process

operators as well as managers.

4.1 Dow Benelux B.V.

Dow Benelux is part of the global Dow Company, and has ten production locations

and three office locations. Dow’s largest production site outside of the United States

is located in Terneuzen (the Netherlands). This site consists of 41 units, of which 26

are factories. The total number of employees at Dow Benelux in 2001 was about

2800, with about 600 in Belgium and 2200 in the Netherlands. It produces more than

800 different products, most of which are semi-manufactured goods for application in

all kinds of products used in aspects of our daily lives. Examples of markets where

Dow is a major ‘player’ are: furniture and furnishings (carpets, furniture materials),

maintenance of buildings (paint, coatings, cleaning materials, isolation), personal care

(soap, creams, lotions, packing materials), and health and medicine (gloves for

surgeons, diapers, sport articles).

Before the 1990s, Dow Chemicals was mainly a “blue collar/manual work”

organization. During the first half of the 1990’s, they suffered hard times and the

company made financial losses. Global competition was increasing and technological

developments were speeding up. Dows’ management concluded that if the company

wanted to survive it had to become more flexible, more responsive, and permanently

alert. Therefore a new strategic plan was developed: the Strategic Blueprint.

This need for change led to the development of a new global HR strategy that

broke with the tradition of job security and switched to career security. Since the mid-

1990s, Dow no longer guarantees a lifelong job, but instead the company offers a

career that can develop at Dow, but also elsewhere. Furthermore, Dow made a switch

from a ‘manual work/blue collar work’ organization towards a ‘brainwork/white

collar work’ organization during the 1990s. Therefore, to transfer the knowledge and

experience from ‘one head to another’ became a very important challenge for the

company.

In 1997, Dow started to introduce the People Success System (PSS): “a system of

Human Resource reference materials and tools that help provide the underpinnings of

116

Dow’s new culture”

1

. Before the introduction of PSS (which is technically based upon

Peoplesoft), Dow already had a number of electronic HR systems in use. PSS’s

difference was that it was based upon the idea of having one database, and more

importantly, with PSS, a completely new HR philosophy was introduced.

Coming up with a new HR strategy was part of the initiative to improve Dow’s

performance after a period of tough years with annual losses of 1 billion US dollars.

The new HR strategy was part of the new so-called Strategic Blueprint, introduced as

a ‘roadmap for the company’s transformation’. Dow wanted to become a real global

company, instead of an internationally dispersed one. In order to achieve this, internal

policies, including HRM, had to be unified. The use of state-of-the-art information

technology to support a new HR policy was seen as the obvious choice! Therefore,

the way forward to the implementation of web-based HR, i.e. e-HRM, was open and

the new HR system was called the People Success System (PSS).

5 The PSS Analysed in Terms of the Organizational Knowledge

Cycle

This section contains the discussion of our proposition, i.e. that transformational

HRIS can usefully be analysed in terms of the Organizational Knowledge Cycle as

put forward at the outset.

5.1 The Knowledge Creation Context: Linking the HR Strategy and Dow’s

Overall Strategy

Dow’s HR strategy, the so-called People Strategy, is rooted in the company’s overall

strategy, the Strategic Blueprint. This People Strategy should ultimately provide the

strategic leadership that is necessary to allow all Dow employees to use their ‘full

potential’. Besides this, the People Strategy has to make employees realize that they

are responsible for their own development in order to support the company in

advancing to the next performance stage. Dow, in response, practices a ‘pay-for-

performance’ philosophy, expresses the sentiment that it wants employees to stay for

a long period of time, and offer employees the possibility to develop themselves and

advance their careers.

Dow’s top management introduced the People Success System as part of the

organizational change process. The PSS is seen as ‘a global, integrated competency-

based Human Resources system for Dow employees’. It includeed four prime

components: performance expectations, compensation, development, and

opportunities. The stated goals of the PSS were:

- To provide an integrated Human Resources system that supports the strategy

of the company and enables the culture required for individual and business

success to flourish.

1

Brochure for employees new to Dow: “Enabling People Success at Dow”

117

- To support a global business organization of empowered employees who

know what to do, know how to do it, and who want to do it: a de-layered

organization with ‘broad spans of control’, self-directed teams, and that has

created a workforce ready for change.

5.2 PSS’s Contribution to the Company’s Formation or Construction of

Knowledge

Overall, people at Dow appreciated the fact that, with the PSS, information became

available that was not previously accessible. The global compensation system

especially received a lot of hits at the beginning, because it provided information

about salaries at all job levels at all Dow sites around the world. People could

compare between countries and between job levels. This contributed to the open

culture that had been announced as part of the HR changes at Dow.

Interestingly, due to the introduction of a whole new HR philosophy, there was so

much information available that it discouraged people from exploring the system. It

could create a feeling of getting lost, not knowing how to find the way. With the

implementation of the web-based version of the People Success System, most of the

information available concerned compensation. The new HRM policy included a new

global compensation system, based upon the idea that compensation had to be

comparable among all Dow sites.

One interesting aspect is that the opinion exists that the PSS stresses very much the

social issues (training, conflict management, language, and social skills) rather than

the professional technical skills. As one person close to this topic said: “We simply

rely on their (new employees) education; presuming that they have their technical and

professional skills. In my view, many mistakes were made in the recruiting of new

employees because of the issues in the system: too much attention is given to the

social aspects and not to the normal professional skills”.

5.3 The Organization of the Company’s Knowledge through PSS

Using PSS’s navigator, employees could find plenty of information about Dow’s HR

philosophy as described earlier, which was in itself very relevant since this was

completely new and different from Dow’s earlier HR approach. Thus, initially, the

PSS was mainly an information provider. However, from the first moment on, new

tools were regularly implemented. Today, Dow Chemicals claims to be one of

companies who have made the largest investments in ICT in recent years. With the

implementation of these tools, the PSS has become more interactive, and provided

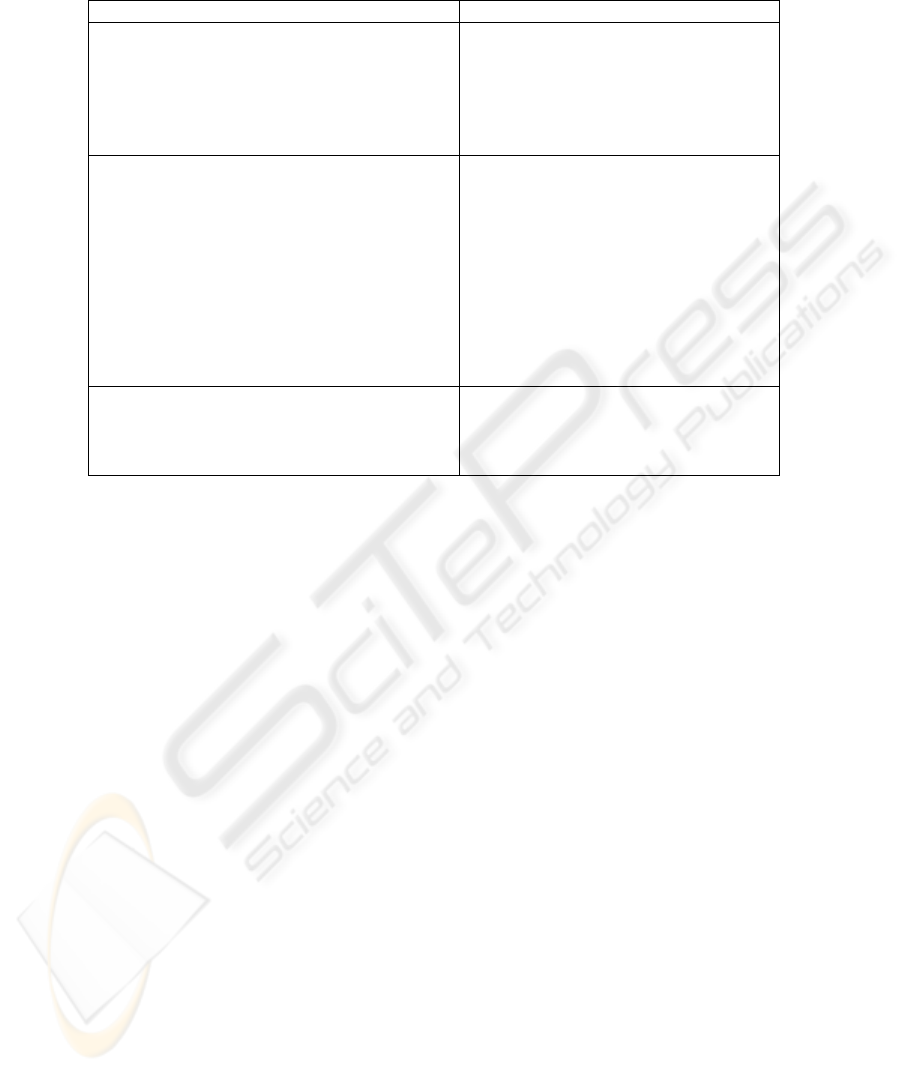

HR instruments to employees and line management. Table 2 provides information

about the main specifications of various components in the PSS.

118

Table 2. Content of the PSS at Dow Chemicals.

Main components of PSS PSS services

Performance expectations

Helping employees understand what is expected

from them in their job, what knowledge, skills

and behavior are required, and how their work

will be evaluated.

•

Job Families

• Competencies

• Development Stages

• Competency matrices

• Competency profiles

• Managing Performance

Development

Helping employees plan their careers: to

develop their knowledge and skills for their

current and future job.

•

Employee Development Process,

e.g.:

- Seek feedback

- Define and Document a Plan

- Implement the Plan

• Employee Development Tools, e.g.:

- 360˚ Development tool

- Mentoring Process

- Managing Personnel Growth

- Learning resources list

- Writing SMART goals

Opportunities

Guiding employees through the opportunities

and career transitions.

•

Career Opportunity Maps, e.g.:

• Job Announcement System

• Future Leader Process

• Succession Planning Process

5.4 PSS’s Capability for Storage or Retention of Knowledge

The PSS initially contained mostly information, much about all the aspects of the HR

policy and the philosophy behind it. Especially the information about the new

compensation system attracted a lot of attention. The system provided information

about the salaries of all the job families at all levels, and in all countries where Dow

has a site. For example, employees could (and did) compare their salaries with those

doing the same job in other countries. Also information about the salaries of the most

senior employees at the company attracted much attention.

5.5 PSS’s Key Capabilities: Distribution, Transfer or Sharing of Knowledge

As the system became more sophisticated, the enthusiasm for using the system itself

increased. Quite soon after the implementation, in 1997, Dow’s Job Announcement

System (JAS) became available. Until then, the people at Dow had been reluctant to

believe that this system would really create the transparent and flexible internal labour

market promised. At Dow, the traditional way of filling vacancies was to contact

friendly colleagues or line managers within the company. Some people expected to be

blocked by their managers if they wanted to apply for a job elsewhere in the

company. However, the JAS has been the greatest success story with the PSS, initially

and still today. Line managers have to publish job vacancies on the JAS, and

employees, right from the very start, have used the opportunities offered to apply

internally for jobs. Some line managers were not pleased by the fact that their

119

employees ‘walked out’, and complained to HR “Help, my people are walking out”.

HR’s reply in such cases was “Then you have a problem” meaning that the line

managers had to work on the way they managed their people.

5.6 The Outcomes of PSS: Aplication, Use or Re-Creation of Knowledge

An overall view is that it took Dow’s employees (line managers and employees in the

plant) three years to get used to the People Success System. By the end of 2004 all

employees had to have a personal development plan. This meant that they had to use

tools in PSS. People were ‘forced’ to schedule time (in advance) to work with the

system, in order to learn how to work at Dow or for personal development.

At the same time we have found an indirect connection: the transparency of the

company has increased and its policies have become more open - the same

information is available to the management and to the employees. The most

impressive example is the openness of the compensation part of the PSS. Salaries of

all positions are visible to everybody, anyone can see how much the leaders earn, and

in all countries.

With the new Strategic Blueprint and the new HR philosophy (competence-based)

there can be more people than before on a senior level within a group of workers.

There can now be more than one ‘first operator’ working on a shift, and an increase in

the number of team members who can do specific tasks, and this makes job rotation

possible.

Since the implementation of the PSS, employees can see how to change and

develop, and this is very new to them. According to some views, the idea of career

self-management is not yet fully working: employees need more time and this has to

be granted by their team leader. Within Dow, a more revealing opinion can be heard

about the opportunities the PSS gives. There is a commonly held view that there are

many examples of individuals who have wanted to develop themselves at Dow, and

who have been successful due to the PSS.

Communication is now very fast and it is very simple to communicate with

anybody. In the plant, however, there are still employees who never check their e-

mail. However, one hears that direct contacts have been dramatically reduced. HR

specialists say that people are now more aware of what the company wants from

them. People are trying to do something about their knowledge and skills. All the

information needed about how to develop is on-line, so there is no need to physically

go to the HR department.

In terms of cost effectiveness, it is difficult to determine whether the PSS has

helped in reducing costs. The e-learning component Learn@dow

has saved money. It

reduced costs in terms of space, time and human resources. The number of courses

that can be offered through the HR intranet is also far more than the number that

could be offered class room-based.

In conclusion, it can be said that the organization’s members, in the first stage of

usage, worked with the PSS mainly as an operational e-HR tool. They used it a source

of information. When more tools and resources were added usage switched, to some

120

extent, towards relational e-HR, albeit with caution. We have concluded this in view

of the fact that young new employees use the competency assessment tool for new

employees right from their start at Dow. They use the development tool to compile

their development plan for the near future and are happy to use learn@dow. In this

way the workforce has become more change ready.

6 Conclusions

In this paper we have put forward the organizational knowledge cycle as a conceptual

tool to analyse the impact of transformational HRIS on the state of organizational

knowledge in the organization, and have used a published case study [7] to illustrate

our proposition. Our aim is to provide an alternative set of epistemological and

methodological tools to analyse transformational HRIS. A question we have asked

ourselves at the outset was whether an intranet-based system was really necessary to

achieve an improvement in the strategic role of human resource management, i.e. a

major transformation, at Dow Chemicals. Our conclusion is that it was indeed

necessary given that an intranet-based system created the opportunity to reach every

employee at any time anywhere around the globe. Information technology also

provided the best opportunities to personalize information (by personalized portals),

to provide a better service to clients and to improve increased efficiency in many

administrative processes.

Besides, it is also clear that a global intranet-based system offered the opportunity

to develop one global standard, a centrally-steered HR policy and global standard HR

practices. Dow’s top management perceived this as advantageous for the company as

the whole. However it also implied opportunities to serve employees better, especially

in giving them more control and also the responsibility to develop themselves: up-to-

date information, relevant electronic links, and relevant instruments to work with

individually. It is also clear that the PSS created opportunities to standardize and

centralize HR processes, and to make HR processes more efficient, for example by

electronic database management, online recruitment, online training, and online

assessment tools.

The PSS has been instrumental in improving skillful practice at Dow which is the

same as saying that it has contributed to an improvement on the organization’s

knowledge. However, in talking of organizational knowledge, it is important to bear

in mind that knowledge is neither “out there”, incorporated in external systems or “in

here”, inscribed in the human brain, but exists as something in people’s ongoing

engagement in social practices. This perspective is compatible with the view that

organizational knowledge can be pragmatically conceptualized as a five-step process

of construction, organization, storage, distribution and application. Each individual

step of such cycle has been discussed by a variety of authors in the organizational

knowledge and learning literatures, giving intellectual validity to this framework. We

hope that future research into HRIS that can take the concept of the organizational

knowledge cycle further by establishing more precise links between the steps of the

cycle and the characteristics of transformational HRIS.

121

References

1. Magalhães, R. Organizational Knowledge and Technology: an action-oriented approach to

organization and information systems. London: E. Elgar (2004).

2. Kogut, B.; Zander, U. “Knowledge of the Firm, Combinative Capabilities and the

Replication of Technology”. Organization Science, 3 (3): 383-397 (1992).

3. Collis, D.J. “How Valuable are Organizational Capabilitites?” Strategic Management

Journal, 15: 143-152 (1994).

4. Teece, D.J.; Pisano, G.; Shuen, A. “Dynamic Capabilities and Strategic Management”.

Strategic Management Journal, 18 (7): 509-633 (1997).

5. Eisenhardt, K. M.; Martin, J. A. “Dynamic Capabilities: what are they?” Strategic

Management Journal, 21: 1105-1121 (2000).

6. Helfat, C. E.; Peteraf, M. A. The Dynamic Resource-Based View: Capability Lifecycles.

Strategic Management Journal, 24 (10): 997-1010 (2003)

7. Ruël, H.J.M. The non-technical side of office technology: managing the clarity of spirit and

appropriation of office technology. Enschede: Twente University Press (2001)

8. Nonaka, I.; Takeuchi, H. The Knowledge Creating Company: how Japanese companies

create the dynamics of innovation. N. York: Oxford University Press (1995).

9. Orlikowski, W. “Knowing in Practice: enacting a collective capabilities in distributed

organizing”. Organization Science, 13 (3): 249-273 (2002).

10. Giddens, A. The Constitution of Society: outline of the theory of structuration. Cambridge,

UK: Polity Press (1984).

11. Maturana, H.R.; Varela, F.J. Autopoiesis and Cognition: the realization of the living.

Dordrecht, Holland: D. Reidel Publishing (1980).

12. Pentland, Brian. “Information Systems and Organizational Learning: the social

epistemology of organizational knowledge systems.” Accounting, Management and

Information Technologies,5(1): 1-21 (1995).

13. Normann, R. “Developing Capabilities of Organizational Learning,” in J. M. Pennings et al.

(ed.), Organizational Strategy and Change. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass (1985).

14. MacDonald, S. “Learning to Change: an information perspective on learning in the

organization”. Organization Science, 6 (5): 557-568 (1995).

15. Lave, J.; Wenger, E. Situated Learning: legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge,

UK: Cambridge University Press (1991).

16. Cohen, W.M.; Levinthal, D.A. “Absorptive Capacity: a new perspective on learning and

innovation.” Administrative Science Quarterly, 35: 128-152 (1990).

17. Marchand, D. (ed) Competing with Information. Chichester: Wiley (2000).

18. Argyris, Chris.: “Organizational Learning and Management Information Systems” in C.

Argyris On Organizational Learning. Oxford: Blackwells (1993).

19. Cohen, M.D. “Individual learning and organizational routines: emerging connections.”

Organization Science, 2 (1): 135-139 (1991).

20. Pentland, Brian; Rueter, H. H. “Organizational Routines as Grammars for Action”.

Administrative Science Quarterly, 39: 484-510 (1994).

21. Walsh, J.R.; Ungson, G.R. “Organizational Memory.” Academy of Management Review,

16: 57-91 (1991).

22. Zuboff, Shoshana. In the Age of the Smart Machine: the future of work and power. Oxford:

Heinemann (1988).

23. Ashforth, B.E. “Climate Formation: issues and extensions.” Academy of Management

Review,10(4): 837-847 (1985).

24. Argyris, C; SCHON, D. A.: Organizational Learning II: theory, method and practice.

Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley (1996).

25. Isaacs, W.N. “Dialogue, Collective Thinking and Organizational Learning”. Organizational

Dynamics, 22 (2): 24-39 (1992).

122

26. Schein, E. Organizational Culture and Leadership. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass (1992).

27. Schein, E. “On Dialogue, Culture and Organizational Learning”. Organizational Dynamics,

22 (Fall): 73-90 (1993).

28. Nonaka, I. “Creating Organizational Order out of Chaos.” California Management

Review,30 (Spring): 57-73 (1988).

29. Bartlett, C.A.; Ghoshal, S. “Beyond the M-Form: towards a managerial theory of the firm.”

Strategic Management Journal,14: 23-46 (1993).

30. Ghoshal, S.; Bartlett, C.A. “Linking Organizational Context and Managerial Action: the

dimensions of quality management.” Strategic Management Journal, 15: 91-112 (1994).

31. Ghoshal, S.; Bartlett, C.A. The Individualized Corporation: a fundamentally new approach

to management. London: Heinemann (1998).

32. Burke, W. W. Organization Change: theory and practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage

(2002).

33. Wright, P., Dyer, L. “People in the e-business: new challenges, new solutions.” Working

paper 00-II, Center for Advanced Human Resource Studies, Cornell University (2000).

34. Lepak, D.P., Snell, S.A. “Virtual HR: strategic human resource management in the 21th

century.” Human Resource Management Review, 8, 215-234 (1998).

123