FORMS OF ENTERPRISE’S AGILITY

Stefan Trzcieliński

Poznan University of Technology, Institute of Management Engineering, Poznan, Poland

Keywords: Agility, Agile manufacturing, Lean manufacturing, Agile enterprise, Virtual enterprise, Information

technology.

Abstract: After lean production, agile manufacturing is considered to be the current paradigm for manufacturing

businesses. However authors who write on this subject use the term as a synonym of agile enterprise, agile

supply chain, and from the other side, even as a synonym of lean manufacturing. Each of these expressions

have a different area of meaning, is connected with different scope of agility, and although in some cases

they cane be used interchangeable, it should be done with an intent. In this paper the different scopes of

agility are treated as its forms. In consistency a presumption is taken that there is no only one proper form of

enterprise’s agility and that contingency approach should be applied when deciding about the form. Each of

these forms are presented including IT that supports the particular form.

1 INTRODUCTION

The business environment becomes more and more

changeable and commonly is described as turbulent

and unpredictable. Since 60’s the production

technologies and management concepts and methods

which were used in mass production, slowly, first in

Japan and next in western countries, have been

replaced by these which constitute lean

manufacturing. In 1991 the Iacocca Institute at

Lehigh University, USA, presented a report, in

which a characteristic of new bases of competition

was included (Goldman, and Preiss, 1991).

According to the researchers, in continuous and

unpredictable changing business environment, to

survive and compete efficiently, a quick respond to

the market, quality improvement and social

responsibility is needed. These features have been

embraced by a new concept which is called agile

manufacturing and is commonly considered to

represent a new paradigm of manufacturing

(Phillips, 1999; Brown and Bessant, 2003; Hormozi,

2001).

Some authors who write on this subject use the

term of agile manufacturing as a synonym lean

production or manufacturing, agile enterprise or

agile supply chain. Each of these expressions have a

different area of meaning, is connected with

different scope of agility, and although in some

cases they cane be used interchangeable, it should be

done with an intent. To minimize the obscure of

meaning of agility, in this paper, a relation between

manufacturing system, production system, an

enterprise as a whole and external value chain is

presented. Agility which relate to each of the

organizational whole is treated as a form of agility.

These forms are contingency determined.

2 MANUFACTURING AS AN OVER

AND SUB-SYSTEM

Manufacturing system transforms the needs and

expectations of the customer into products (goods or

services) which are delivered to him (Armstrong,

1994). Thus the systems encompasses mutually

alternated stream of information and decision and

stream of energy and materials. The last one which

transforms an energy and material inputs into goods

and services is called a production process and

together with its controlling process creates a

production system. Production line or production

cell are examples of production system. Contrary to

some authors, in this paper production system is

meant as a subsystem of manufacturing system

(Figure 1). From the other side manufacturing is one

of a lot subsystems of the whole enterprise, which in

a row, is a subsystem of the network of enterprises

arranged in supply/value chain (it is worth to notice

397

Trzcieli

´

nski S. (2007).

FORMS OF ENTERPRISE’S AGILITY.

In Proceedings of the Ninth International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems, pages 397-403

Copyright

c

SciTePress

that some authors (Ramasesh at al., 2001) define

manufacturing system as a network of enterprises).

Consequently, when talking about agile production

system, agile manufacturing system, agile enterprise

or agile value chain, the consistent researcher should

distinguish the areas of interest, as other wise, the

meaning of agility is obscured. Particular that

concerns widely meant IT, as some technologies are

dedicated only to particular scope of agility.

Figure 1: Manufacturing system (Armstrong, 1994, p.129).

3 FORMS OF AGILITY

3.1 Agile Manufacturing – Enterprise

Internal View Point

3.1.1 Agile Manufacturing as a Lean

Manufacturing

Some authors treat agile and lean manufacturing

interchangeable. Even if they writ about “agile

manufacturing” they describe the same managerial

and production concepts and methods which

constitute lean manufacturing (Brennan, 1994;

Ikonen, et al., 2000). Particular it concerns such so

called new concepts and methods as: Total Qualit

Management (TQM), Concurrent Engineering (CE),

Outsourcing (OS), Total Productive Maintenance

(TPM), Supply Chain Partnering (SCP), Team

Based Working (TBW), Empowerment (EMP), Just

in Time (JiT), Manufacturing Cells (MC), Integrated

Computer-Based Technologies (ICT), Business

Process Reengineering (BPR), and Learning Culture

(LC). Such approach has partly its source in

observation that manufacturing can not be agile if is

not lean, and is not lean when there are big stocks,

production is led in big batches and respond to the

customer is slow (Goldman, et al., 1995). Thus way

concepts and methods of lean manufacturing are also

basic concepts and methods of agile manufacturing

(Figure 2).

However such view point on mutual

compatibility between both concepts obscures their

ideas which are different (Kidd, 2006). The key

point to distinguish both concepts is the life time of

opportunities which the enterprise is focused on.

Lean manufacturing is concentrated on long life time

opportunities. Such opportunities ensure some level

of stabilization, so the company can optimize the

resources which it has to posses. The optimisation

depends on eliminating each symptom of wasting

(Hormozi, 2001; Jin-Hai, et al., 2003; Paez at al.,

2004).

Contrary “agility” is a concept depending on

using short life time opportunities. Such

opportunities are generated by rapid, continuous and

unpredictable changes in business environment

(Goldman et al., 1995; Varnadat, 1999; Zhang and

Sharifi, 2000). More less the same set/system of

managerial methods is exploited in both lean and

agile manufacturing. The goal however is different;

lean manufacturing uses them to reduce wasting

when agile manufacturing implements these

methods to improve the ability to respond quickly

for changes of competitive environment.

Figure 2: Some concepts, methods and practices used by

lean and agile manufacturing (Trzcielinski, 2006).

3.1.2 Agile Manufacturing as the Ability to

Supply Customized Products

A range of publications emphasize that ability to

deliver a product fully adjusted to the customer

needs and expectations is the defining feature of

agile manufacturing (Homrozi, 2001; McCullen and

Towill, 2001; Toussaint and Cheng, 2002; Jin-Hai at

al., 2003; Brown and Bessant, 2003). Such product

is high quality, costs cut and with short delivery time

and able to be upgraded or reconfigured. To build

such product the company looks mostly for

opportunities at existing market of its customers.

They change their expectation about the product

under influence of different environmental factors so

the enterprise has to recognize its customers needs.

The basic role in such model of agility is played by

marketing forces which have to identify the

expectations and needs and pass them to R&D and

engineering staff. To shorten the lead time to the

market methods like CE and TBM have to be

TQM

JiT

CE

EMP

ICT

LC

CI

SCP

BEN

OS

TBW

MC

TPM

BPR

Lean

manufacturing

Agile

manufacturing

TQM

JiT

CE

EMP

ICT

LC

CI

SCP

BEN

OS

TBW

MC

TPM

BPR

Lean

manufacturing

Agile

manufacturing

Delivery

to

customer

Customer

wants and

needs

Product

design

Manufacturing

planning and

control

Manufacturing

process

Feedback – customer satisfaction

Feedback - performance

Delivery

to

customer

Customer

wants and

needs

Product

design

Manufacturing

planning and

control

Manufacturing

process

Feedback – customer satisfaction

Feedback - performance

ICEIS 2007 - International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

398

implemented and appreciate IT must support the

teams. These broadly meant information technology

includes computer numerical control (CNC),

automated guided vehicle (AGV), automated

material handling (AMH), direct numerical control

(DNC), automated assembly (AA), robots and FMS

in production subsystem (Vastag at al., 1994; Zhang

and Sharifi, 2000) and lot of tools supporting

designing and engineering. Among others, they

encompass CAD, CAM, CAE, virtual reality (VR),

rapid tooling (RT), Reverse Engineering Systems

(RE), and rapid prototyping technology (RPT) that

can be integrated with FMS, (Onuh and Hon, 2001;

D&ME, 2006) (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Product customization and quick respond tools

of agile manufacturing.

3.1.3 Agile Manufacturing as the Ability to

Create the Ceeds of Existing and New

Customers

Agile manufacturing system not only identify and

satisfy the expectations of their customers but create

a demand for needs which are out of the customer

awareness (Maskell, 2001; Brown and Bessant,

2003). For instance who of owners of mobile phone

was aware in middle 90’ that he needs his mobile

phone to take photos, listening to the radio or

watching TV? This possibilities of mobile phones

were presented in the electronics fear in Geneva in

1998 and from that time people have started to feel

these needs.

Creating needs is qualitative different approach

that only satisfying them. The priority is given not to

marketing but to R&D functions. It requires wider

and deeper knowledge, new ideas and creativity

(Maskell, 2001; Jackson and Johansson, 2003). As

innovative staff is essential, learning organization

and knowledge management become crucial

concepts and practices.

These leads to changes of the model of

manufacturing that we can see in multinational and

global corporations. They concentrate the R&D

functions in few places and pass the production

functions to its subsidiaries and divisions located

where the production can be the chipset. Some small

and medium businesses do in the same way – they

concentrate their activities on R&D and outsource

the production and supportive functions.

Particular in big corporations the knowledge is

dispersed. Teams, including concurrent engineering

teams, are not co-locative. This generates the need

for IT supporting distributed o virtual teams

working. Variety of commonly used technology is

available, including internet, extranet, intranet,

video-conferencing (Trzcielinski and Wojtkowski,

2007) as well as some dedicated technology

supporting project management. Examples can be

systems like MS Project, Prima-Vera, Pert Master or

PKOnline – system which is used in VW to support

continuous improvement distributed teams working

and knowledge sharing (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Tools to support distributed team working.

3.2 Agile Manufacturing – Network

View Point

3.2.1 Agile Production in Virtual

Work-floors

The traditional enterprise which looks for wide

range of opportunities in turbulent and unpredictable

environment meats a problem that it does not know

if production system it has (technologies, machines,

workers competencies, etc.) will be useful to

undertake the future opportunities. One of solution

to cope with this problem is to build an excessive

production system which will be able to run a big

variety of task. However this solution is extremely

costly and irrational (Jin-Hai at al., 2003;

Trzcielinski and Rogacki, 2004). The other one

depends on using unlimited capacity of external

TQM

JiT

CE

EMP

ICT

LC

CI

SCP

BEN

OS

TBW

MC

TPM

BPR

Lean

manufacturing

Agile

manufacturing

Internet

Extranet

Intranet

IT for distribu-

ted knowledge

management

IT for project

management

AMH

DNC

AA

FMS

CAD

CAM

CAE

RP

RT

RE

VR

TQM

JiT

CE

EMP

ICT

LC

CI

SCP

BEN

OS

TBW

MC

TPM

BPR

Lean

manufacturing

Agile

manufacturing

Internet

Extranet

Intranet

IT for distribu-

ted knowledge

management

IT for project

management

AMH

DNC

AA

FMS

CAD

CAM

CAE

RP

RT

RE

VR

TQM

JiT

CE

EMP

ICT

LC

CI

SCP

BEN

OS

TBW

MC

TPM

BPR

Lean

manufacturing

Agile

manufacturing

AMH

DNC

AA

FMS

CAD

CAM

CAE

RP

RT

RE

VR

TQM

JiT

CE

EMP

ICT

LC

CI

SCP

BEN

OS

TBW

MC

TPM

BPR

Lean

manufacturing

Agile

manufacturing

AMH

DNC

AA

FMS

CAD

CAM

CAE

RP

RT

RE

VR

FORMS OF ENTERPRISE’S AGILITY

399

suppliers which are chosen up to the current needs

determined by the opportunities the enterprise

undertakes. Usually the enterprise keeps in its own

structure production of some parts and technological

phases like assembly, which add the key value to the

final product and from the enterprise view point are

subject of technology secret. Production of other

elements is outsourced.

Easy, in technological sense, parts and processes

are moved to small and medium businesses. Market

of them is usually highly competitive. The contracts

are short (small batches of products, short delivery

time); shorter is the life time of the opportunity,

more abrupt are the contracts. The occasion

determined partners are chosen on the base of

cost/price competitiveness as usually they meet the

technological and quality requirements without

troubles. Such partners are recognized as virtual

production work-floors (VWFs).

The enterprise using virtual work-floors superbly

increases its agility, as it is able to produce a wide

range of products possessing limited capacities and

keeping fixed costs on stable level in a long run

(Hormozi, 2001).

Technologically difficult parts and processes are

passed to partners on the base of long time

agreement and alliances (SCP). Such production

requires specialized both technology and knowledge.

In this way relatively enduring supply chain (SC) is

created. Example of such chain is shown on figure 5.

Figure 5: Example of supply chain.

Supply chains have highly specialized links and

therefore are more stiff and less reconfigurable.

Although the links represent advanced level of

technology, there is rather low risk that the supplier

will do forward product acquisition. That is because

of narrow and deep specialization of the chain links.

The above two situations – virtual work-floors

and chain of suppliers requires different IT to

manage the cooperation. In defiance of some

opinions, to manage the VWFs, no especial IT is

needed. As it turned out in research undertaken in

this field in Institute of Management Engineering –

Poznan University of Technology, mostly use of

stationary and mobile phones, internet, e-mail and

communicators is enough. That is because

coordination in this case depends on passing through

the communication channel simply information

about what, how many and when must be done.

Usually the subcontractor does not need any especial

technical assistance from the final manufacturer.

However in case of supply chains, there is necessity

for some standardization of IT which is used by

partners. This concerns for instance MRP II/ERP

systems, CAD, VR, work flow systems (WF) so data

and solution generated in one link of the chain could

be used in another one (McCullen and Towill,

2001).

3.2.2 Agile Virtual Enterprise

To be agile, in terms of being aggressive in creating

opportunities for profit and growth (Goldman and

Preiss, 1991, p.43) the organization has to ensure

brightness (nimbleness), flexibility, intelligence and

shrewdness for the enterprise. No single one of the

features is enough to be agile; they must exist all

together. Because of that they are considered to be

morphological components of agility (Trzcielinski,

2006).

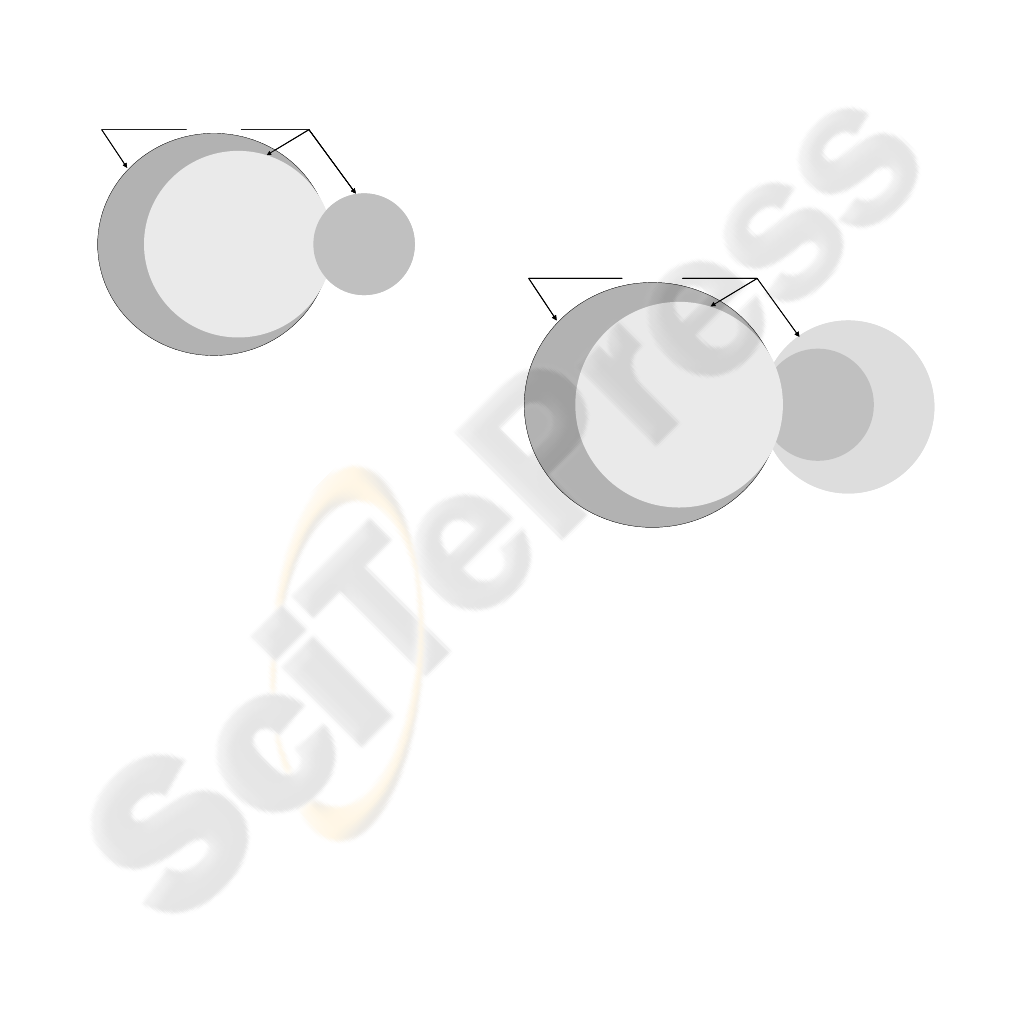

Brightness of Enterprise

To be agile the enterprise has to be able to perceive

quickly market opportunities and threats flowing

from the environment. The opportunities are

independent on the enterprise and going by market

situations, which are the necessary conditions to act

in manner leading to desirable effect o goal. This

component of agility is called here the brightness.

The diversity of opportunities increases with grow of

changes in the environment as the changes evoke

events and tangles of events create situations

including opportunities. The scope of potentially

available opportunities is called here the strip of

opportunities (Figure 6). Better the brightness of

enterprise the wider is the strip of opportunities. In

this sense, the brightness is a function transforming

the turbulent environment into the strip of potential

market opportunities.

Flexibility of Enterprise

The scope of access to the potentially available

opportunities stays in relation with the enterprise

specialization. Specialization depends on narrowing

the diversity of undertaken activities. The scope of

specialization is determined by available and owned

resources. More homogeneous are possessed

resources narrow is the specialization of the

enterprise. That means that the resources determine

the width of strip of available market opportunities.

It is called here a strip of resource available

opportunities.

Producers

of leather

Producers

of fabric

Producers of

car upholstery

Producers

of car chairs

Car assemblers

Producers

of leather

Producers

of fabric

Producers of

car upholstery

Producers

of car chairs

Car assemblers

ICEIS 2007 - International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

400

Resources are available in result of purchasing

them (own resources) or by subcontracting the work.

In the second case a network enterprise is created.

Own resources can be more or less multi-objected,

that means they can be used to realize wider or

narrow repertoire of tasks. Broaden repertoire of

task is possible when general purpose resources are

used. The universality of resources can be traditional

(like in case of general purpose machines or multi-

job workers) or flexible (like in case of flexible

manufacturing systems).

Like own resources also subcontracting creates

possibility of broadening the repertoire of realized

tasks. It depends on the character of the network the

enterprise creates or belongs to. In static networks

like strategic alliances, consortiums, supplier-

subcontractor, cooperative agreements or

outsourcing contracts, the repertoire of possible

tasks to be perform is narrow than in dynamic

networks like virtual work-floor.

The feature of resources available for the

enterprise depending on possibility of extending the

scope of their use, and the same on extending the

repertoire of the task which can be realized with use

of these resources, is called resource flexibility of

enterprise. It is the second morphological component

of agility. Larger is the resource flexibility, wider is

the strip of resource available opportunities (Figure

6). In that sense the resource flexibility of enterprise

is a function transforming the strip of potential

market opportunities into strip of resource available

opportunities.

The Intelligence of Enterprise

The intelligence of enterprise is its ability to

understand the situations in which it functioning and

finding intentional reactions in these situations. The

reactions depend on activating proper resources to

eliminate or reduce harmful influence of these

situations (threats) or to use occasions

(opportunities). The intelligent enterprise exploits

the following resources: material, financial, people

and knowledge. They are activated to move from

one to other resource available opportunities. In that

sense the intelligence is a function transforming the

strip of resource available opportunities into strip

available opportunities and constitutes the third

morphological component of agility (Figure 6).

Shrewdness of Enterprise

From definition, opportunities are going by

situations. The life time of market opportunity

depends on the changeability of the enterprise’s

environment. It gets shorter when the changeability

increases. More short life time and narrow is the

strip of the opportunities more difficult to achieve

them. The ability of enterprise to use quickly the

opportunities in beneficial mode are called here the

enterprise’s shrewdness and is considered to be the

forth morphological component of the agility

(Figure 6).

Figure 6: Agility as a function transforming environmental

turbulences into a strip of opportunities used by the

enterprise.

The only form of enterprise which enable to

obtain all the morphological features of agility is

virtual organization. The virtual organization is a

temporary configuration of partners working

together for achieving bargain goals. The aspect of

reconfigurability and the same temporality of

partners, is appointed by authors writing on the

organization of the future, to be a vital feature of

virtual organization (Galbraith, 1997, p.89; Cunha

and Putnik, 2006, p. 36-40).

The opportunistic and temporary character of the

relations means that virtual organization

reconfigures itself, so it has a dynamic structure. The

changeable components (partners), which are taken

from the environment, cause that the boundary

between the virtual organization and the

environment becomes fuzzy. Because of this it is

invisible for its customers (Handy, 1997).

The virtual organization bases on team working.

It exploits the mutual adjustment mechanism of

coordination which depend on informal and direct

contact between team members. The mechanism is

efficient when the partners conform their actions to

the achievement of common goal and express the

willingness of cooperation. The mutual adjustment

means that there is not only one coordination and

decision centre and that such centre is emerged

spontaneously according to the core competencies

possessed by a partner. The decision centre moves

from one to another partner who has the key

Changes in environment

Threats

Opportunities

Strip of potentially

available

opportunities

Strip of resource

available

opportunities

Strip of available

opportunities

Strip of used

opportunities

Changes in environment

Threats

Opportunities

Strip of potentially

available

opportunities

Strip of resource

available

opportunities

Strip of available

opportunities

Strip of used

opportunities

FORMS OF ENTERPRISE’S AGILITY

401

competencies in particular phase of the project. In

results the hierarchy is replaced by heterarchy.

There is a long organizational distance between

partners in virtual organization. In case of network

of institutional enterprises the distance is determined

mostly by the location and social distance. Quite

often the dispersed location is assisted by time

distance. Both features make not only weaker the

social relations among partners but difficult to build

the climate of their trust, which is one of the powers

integrating partners within virtual organization

(Handy, 1997; Jin-Hai at al., 2003).

The reduction of the negative influence of

location, time and social distance is possible by

selecting competent partners and implementation of

IT enabling effective communication and quick

access to the common data basis. In this way the

organizational distance and particular its information

component becomes shorter. The information

technology gives the organization a new quality and

is an essential attribute of virtual organization.

Virtual Enterprise implements different forms of

cooperation among partners including e-commerce,

e-business, e-marketplace, e-negotiations, e-

contracts and others (Cunha and Putnik, 2006, p.

150-181). All these forms require Internet and Web-

based systems which provide support to them.

Additionally intelligent agent-based solution are

technologies which can be appropriate in both

virtual organization (searching for partners) and

electronic commerce (searching for products and

services) (Cunha and Putnik, 2006, p.149) (Figure

7).

Figure 7: IT supporting transition from lean manufacturing

to agile enterprise.

4 CONCLUSIONS

Agility is not state, it is process. Perhaps it starts

from agile manufacturing where the enterprise is

focused on product customisation and short time

delivery of the product to the market. Just then, as

regards of concepts and methods which are used,

agile manufacturing looks like lean manufacturing.

However both concepts differ each other. Lean

manufacturing and lean enterprises looks for long

life time opportunity when agile manufacturing and

agile enterprise caches short time opportunity. The

opportunity can be searched for at existing

customers market or in any market when a demand

appears or has been created for certain products or

services. More changeable is the business

environment more opportunities appears. Agile

virtual enterprise is an organization which copes

with such “unfriendly” environment. In fact such

environment justify the sense of its existence.

Agility is not possible without IT. The concept

has got to practice in result of IT development. That

concerns technologies aided design, engineering,

manufacturing, production, etc. New possibilities

appeared when Internet and internet technologies

became available. Just than distributed engineering

and distributed work could enhanced on upper level

up to purely virtual organization, as technology like

work flow systems, distributed knowledge

management, supply chain management, e-business,

intelligent based-agents and a lot of others made

them realistic.

REFERENCES

Armstrong, A.M., 1994. A Handbook of Management

Techniques. Kogan Page, London.

Brennan, L., 1994. The Formation of Structures, Roles and

Interactions within Agile Manufacturing Systems. In

Kidd, P.T, Karwowski, W. (Eds), Advances in Agile

Manufacturing. IOS Press, Amsterdam.

Brown, S., Bessant, J., 2003. The manufacturing strategy-

capabilities links in mass customization and agile

manufacturing – an exploratory stud, Vol. 23 No.7.

Cunha, M.M., Putnik, G.D., 2006. Agile Virtual

Enterprises: Implementation and Management

Support, Idea Group Publishing, Hershey.

D&ME, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, 2006,

Agile Manufacturing, www.technet.pnl.gov/dme/agile/

Galbraith, J.,1997. The Reconfigurable Organization. In:

The Organization of the Future, (Eds.) F. Hesselbein

et al.,. Josseu-Bass Publishers, San Francisco.

Goldman, S.L, Nagel, R.N, Preiss K., 1995. Agile

Competitors and Virtual Organization. Strategies for

Enriching the Customer. Van Nostrand Reinhold, New

York.

Goldman, S.L., Preiss, K., (eds.); Nagel R.N., Dove R.,

principal investigators, with 15 industry executives,

1991. 21

st

Century Manufacturing Enterprise

TQM

JiT

CE

EMP

ICT

LC

CI

SCP

BEN

OS

TBW

MC

TPM

BPR

Lean

manufacturing

Agile

enterprise

Internet

Extranet

Intranet

IT for distribu-

ted knowledge

management

IT for project

management

AMH

DNC

AA

FMS

CAD

CAM

CAE

RP

RT

RE

VR

Standardization

of IT used in the

supply chain

WF management

systems

Intelligent agent-

based solutions

IT supporting

e-commerce,

e-business,

e-marketplace,

e-negotiations,

e-contracts

TQM

JiT

CE

EMP

ICT

LC

CI

SCP

BEN

OS

TBW

MC

TPM

BPR

Lean

manufacturing

Agile

enterprise

Internet

Extranet

Intranet

IT for distribu-

ted knowledge

management

IT for project

management

AMH

DNC

AA

FMS

CAD

CAM

CAE

RP

RT

RE

VR

Standardization

of IT used in the

supply chain

WF management

systems

Intelligent agent-

based solutions

IT supporting

e-commerce,

e-business,

e-marketplace,

e-negotiations,

e-contracts

ICEIS 2007 - International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

402

Strategy: An Industry-Led View, 2 volumes, Iacocca

Institute at Lehigh University, Bethlehem, PA.

Handy, Ch., 1997. Unimagined Future. In: The

Organization of the Futute, (Eds.) F. Hesselbein at al.,

Josseu-Bass Publishers, San Francisco.

Hormozi, A.M., 2001. Agile manufacturing: the next

logical step. Benchmarking: An International Journal,

Vol. 8 No., 2.

Ikonen, I., Kantola, J., Kuhmonen, M. 2000. Approach to

Agile Manufacturing for Multinational Manufacturing

Company. In Marek, T., Karwowski, W. (Eds),

Human Aspects of Advanced Manufacturing: Agility &

Hybrid Automation – III. Institute of Management –

Jagiellonian University.

Jackson, M., Johansson, C., 2003. An agility analysis from

a production system perspective. Integrated

Manufacturing Systems, Vol. 16 No. 6.

Jin-Hai L., Anderson A.R., Harrison, R.T., 2003. The

evolution of agile manufacturing. Business Process

Management Journal, Vol. 9 No.2.

Kidd, P.T., 2006. Agile enterprise strategy: a next

generation manufacturing concept.

Maskell, B., 2001. The age of agile manufacturing. Supply

Chain Management: An International Journal, Vol. 6

No. 1.

McCullen, P., Towill D., 2001. Achieving lean supply

through agile manufacturing. Integrated

Manufacturing Systems, Vol. 12 No. 7.

Onuh, S.O., Hon, K.K., 2001. Integration of rapid

prototyping technology into FMS for agile

manufacturing. Integrated Manufacturing Systems,

Vol. 12 No. 3.

Paez, O., Dewees, J., Genaidy, A., Tuncel, S., Karwowski,

W., Zurada, J., 2004. The Lean Manufacturing

Enterprise: An Emerging Sociotechnological System

Integration. Human Factors and Ergonomics in

Manufacturing, Vol. 14 No. 3.

Phillips, L., 1999. Agile manufacturing in the aerospace

industry: an industrial viewpoint. International

Journal of Agile Management Systems, Vol. 1 No.1.

Ramasesh, R., Kulkarni, S., Jayakumar, M., 2001. Agility

in manufacturing systems: an exploratory modeling

framework and simulation. Integrated Manufacturing

Systems, Vol. 12 No. 7.

Toussaint, J., Cheng, K., 2002. Designing agility and

manufacturing responsiveness on the Web. Integrated

Manufacturing Systems, Vol. 13 No. 5.

Trzcielinski S., Rogacki P., 2004.The model of virtual

workshop of manufacturing company. In Proceedings

of the Ninth International Conference on Human

Aspects of Advanced Manufacturing: Agility and

Hybrid Automation, E.F. Fallon, W. Karwowski

(Eds.), The Department of Industrial Engineering,

National University of Ireland, Galway.

Trzcielinski, S., 2006, Models of Resource Agility of an

Enterprise. In PICMET’06, Proceedings of

International Conference on Technology Management

for the Global Future, Portland International Center

for Management of Engineering and Technology,

Istanbul, Turkey, CD product.

Trzcielinski, S., Wojtkowski, W., 2007. Toward the

measure of organizational virtuality.

Human Factors

and Ergonomics in Manufacturing, Vol. 17 No. 5 (in

production).

Varnadat, 1999. Research agenda for agile manufacturing.

International Journal of Agile Management Systems,

Vol. 1 No.1.

Vastag, G., Kasarda, J.D., Boone, T., 1994. Logistical

Support for Manufacturing Agility in Global Markets.

International Journal of Operations & Production

Management, Vol. 14 No. 11.

Zhang, Z., Sharifi, H., 2000. A methodology for achiving

agility in manufacturing organizations. International

Journal of Operations & Production Management,

Vol. 20 No. 4.

FORMS OF ENTERPRISE’S AGILITY

403