CRITICAL SUCCESS FACTORS OF INTERNET SHOPPING IN

JAPAN: CUSTOMER-CENTRIC

AND WEBSITE-CENTRIC PERSPECTIVES

Kanokwan Atchariyachanvanich

Graduate University for Advanced Studies, Shonan Village, Hayama, Kanagawa, 240-0193 Japan

Hitoshi Okada, Noboru Sonehara

National Institute of Informatics, 2-1-2 Hitotsubashi, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo, 101-8430 Japan

Keywords: Internet shopping, critical success factors, technology acceptance model, customer-centric, website-centric.

Abstract: The results from a study conducted on the effect of factors on the customers’ attitude toward using Internet

shopping in Japan are presented in this paper. The research model was an extended version of the

consumers’ acceptance of virtual stores model with the addition of a new factor, need specificity, grouping

critical success factors based on their customer-centric and website-centric perspectives sources, and

examining how the differences in customer characteristics affect the actual use of Internet shopping. The

results of an online questionnaire filled out by 1,215 Japanese online customers pointed out that gender,

education level, innovativeness, net-orientation, and need specificity, factors of customer-centric

perspective, have positive impacts on the actual use of Internet shopping. The implication also shows that

Japanese online customers do not consider the service quality of Internet shopping, a factor of the website-

centric perspective, as significantly as offline customers do.

1 INTRODUCTION

Internet shopping has been introduced as an

electronic commerce (EC) application since the

early 1990s (Turban et al, 2002). The long-term

forecast of worldwide EC spending done by the

research firm International Data Corporation (IDC)

is expected to reach $7,127 billion by 2007

(International Data Corporation, 2004). The actual

amount of worldwide EC spending has feverishly

increased by 349.81 percent from 2000 to 2003.

However, in Japan, the growth rate in EC spending

has decreased from 39.26% in 2001 to 30.26% in

2003 (IDC, 2004). Two possible reasons for this

phenomenon are that the number of new online

customers and a number of returning online

customers are decreasing. These raised two

questions, what makes online customers purchase

from the Internet and what keeps online customers

repurchasing through the Internet. However, a better

understanding of the factors affecting the purchase

decision can provide a crucial grasp of the consumer

behavior in cyberspace (Limayem et al., 2000).

Since the purchasing decision process certainly

happens before the repurchasing process, we need to

investigate it first. Moreover, the Japanese market

characteristics are a mystery to most foreign

observers and the consumption behavior of Japanese

customers is notably different from other societies

(Synodinos, 2001). This study, thus, focuses on

these factors and the online customers’

characteristics influencing Internet shopping in

Japan.

The objectives of this study were to investigate

the factors influencing the actual use of Internet

shopping by using the consumers’ acceptance model

and to explore how differences in customer

characteristics affect the actual use of Internet

shopping by using a statistical analysis. This paper is

one of the first studies to examine the key factors

underlying customers’ purchasing intentions through

the Internet in Japan, by grouping them into two

views of their sources, customer and website

(Atchariyachanvanich and Okada, 2006a). This

paper is set up as follows. Section 2 presents an

overview of Internet shopping in Japan, its relevant

theories and factors, as well as develops the

261

Atchariyachanvanich K., Okada H. and Sonehara N. (2007).

CRITICAL SUCCESS FACTORS OF INTERNET SHOPPING IN JAPAN: CUSTOMER-CENTRIC AND WEBSITE-CENTRIC PERSPECTIVES.

In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on e-Business, pages 261-268

DOI: 10.5220/0002111202610268

Copyright

c

SciTePress

hypotheses. Section 3 discusses the research method.

In Section 4, the empirical data will be analyzed and

discussed. Section 5 concludes with the findings and

implications for research and practice.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Internet Shopping and Consumer

Behaviour in Japan

Regarding a preliminary online survey of the factors

affecting each online shopping process in Japan, the

consumer behavior of online customers of the goo

Research of NTT Resonant Inc. in Japan showed

that price is the dominant factor that makes goo

online customers shop online (Atchariyachanvanich

and Okada, 2006b). This is because it is difficult to

buy a product at a low price from traditional shops

in Tokyo where living expenses are the highest in

the world. Moreover, Internet shopping offers the

customers products that are not available at

traditional shops. Internet shopping is thus a way for

customers in high-cost-of-living countries like Japan

to seek cheap and rare products. This survey called

for further study on what else makes Japanese

customers purchase through the Internet and what

characteristics of Japanese customers affect their use

of Internet shopping.

2.2 Critical Success Factors

Recently, several researchers have investigated the

predictors of what makes customers purchase

through the Internet (Limayem et al., 2000; Chen et

al., 2004; Blake et al., 2003; Pavlou, 2003; Verhoef

and Langerak, 2001; Chen et al., 2002). The model

frequently employed to conduct this investigation is

the technology acceptance model (TAM) (Kwong et

al., 2002). Chen et al. (2004) conducted one of the

more outstanding studies that developed the

consumers’ acceptance of virtual stores theoretical

model. Their study not only proposed the

consumers’ acceptance of virtual stores model based

on the technology acceptance model (TAM) and the

innovation diffusion theory (IDT), but also unified

the five critical success factors (CSF) that include

product offerings, information richness, usability of

storefront, perceived service quality, and perceived

trust. With the strengths of Chen et al.’s study

including the theoretical model and CSFs for virtual

stores, it was used as a based model to develop the

research model of this study. However, these CSFs

are a combination of customer and website factors.

In the EC market, there are three entities interact

with each others, EC company, EC website, and EC

customer (Atchariyachanvanich and Okada, 2006a).

Each entity consists of several factors that are

further classified as critical success factors. CSFs

can be managed and/or built by the EC company in

order to achieve the business’s goals. The CSF

classification of each entity is thus important in

helping the EC company enhance its EC website and

serve its EC customers. Thus, this study groups

these CSFs into two categories based on their entity.

2.2.1 Customer-Centric Perspective

Customer-centric perspective is defined as a

subjective factor that occurs to customers

themselves and affects the actual use of Internet

shopping, such as customer characteristics, trust in

the Internet shopping, compatibility of Internet

shopping, and customer’s need.

Customer characteristics: A consumers’

personality characteristics influence their Internet

shopping behavior (Cao and Mokhtarian, 2005).

Age is found to have an influence on their

Internet shopping behavior, that is the higher a

customer’s age, the more likely that person will buy

online (Bellman et al., 2000; Bhatnagar and Sanjoy,

2004). In addition, older people would find Internet

shopping more attractive because their lives are

generally more time-constrained (Bhatnagar and

Sanjoy, 2004). Thus, we propose:

H1: The older the customer, the higher the level

of actual Internet shopping use.

Gender is a significant predictor of a customer’s

purchasing intentions through the Internet (Slyke et

al., 2002; Koyuncu and Bhattacharya, 2004). It was

found that male respondents were more likely than

female respondents to purchase products and/or

services through the Internet. Therefore, we

hypothesize that:

H2: Male customers have higher levels of actual

Internet shopping use than female customers.

Marital status is insignificantly found to

influence an Internet shopping behavior (Raijas and

Tuunainen, 2001). Thus, we propose:

H3: Marital status influences a customer’s actual

Internet shopping use.

Income is a determinant of purchasing power.

The higher a person’s income, the more likely that

person will buy online, and the higher a person’s

income, the more online transactions that person is

likely to make (Bellman et al., 2000). Thus, we

propose:

H4: The higher the income level, the higher the

level of actual Internet shopping use.

ICE-B 2007 - International Conference on e-Business

262

Education level also influenced consumer

behavior. The higher a customer’s education is, the

more likely they will purchase through the Internet

(Bellman et al., 2000). Thus, we propose:

H5: The higher the education level, the higher

the level of actual Internet shopping use.

Innovativeness is often identified as a personality

construct, and has been employed to predict a

customer’s innovative tendencies to adopt a variety

of technological innovations (Yang, 2005).

Innovativeness was found to be positively associated

with the adoption of Internet shopping (e.g., Blake et

al., 2003; Limayem et al., 2000).

Purchasing through

the Internet is an innovative behavior that is more

likely to be adopted by innovators than non-

innovators (Limayem et al., 2000).

This leads to the

following hypothesis:

H6: The higher the level of innovativeness, the

higher the level of actual Internet shopping use.

Net-orientation is the subjective factor for

predicting the online buying behavior that indicates

if typical online customers are “wired lifestyle”

people who have been on the Internet for years, or

those who have been online for just a few months.

Wired-lifestyle people tend to be net-oriented style

(Bellman et al., 2000). They use the Internet not

only to improve their productivity at work but also

for most other activities, such as reading the news.

Net-oriented people are therefore defined as people

who are interested in and make use of Internet

applications. As customers become more wired to

the Internet, their intention to purchase items on it

may increase. Thus, we purpose:

H7: The higher the level of net-orientation, the

higher the level of actual Internet shopping use.

Perceived trust: Lack of trust in online

businesses is one of the main reasons for customers

not purchasing items through Internet shopping

(Hoffman et al., 1999; Pavlou, 2003). Customers are

reluctant to input their personal information when

Internet shopping sites asks for it. In addition, they

are concerned about the interception and misuse of

information sent over the Internet. Consequently,

they may not trust online shopping. This leads to the

hypothesis:

H8: A customer’s perceived trust in Internet

shopping positively influences his or her attitude

toward using it.

Compatibility: The degree to which consumers

perceive Internet shopping to match their shopping

needs and to be consistent with the existing values

and beliefs (Verhoef and Langerak, 2001; Chen et

al., 2002). We propose:

H9: The compatibility between using Internet

shopping and a customer’s needs positively

influences his or her attitude toward using it.

H10: The compatibility between using Internet

shopping and a customer’s needs positively

influences his or her perceived usefulness of it.

Need specificity: The specificity of the

customer’s needs with respect to how well

customers consider what they want when they visit a

store (Koufaris et al., 2001). We hypothesize that:

H11: The customer’s need specificity positively

influences his or her attitude toward using it.

2.2.2 Website-Centric Perspective

Website-centric perspective is defined as a factor

that is created by an EC company to fulfill the

marketing strategy and to be a successful website in

the EC market. In other words, this category

represents the EC company.

Ease of use: The degree to which customers

expect to effortlessly use Internet shopping (Chen et

al., 2002). In line with previous studies, we propose:

H12: The ease of use of Internet shopping

positively influences a customer’s attitude toward

using it.

H13: The ease of use of Internet shopping

positively influences the usefulness of it.

Usefulness: The customer’s probability that

using Internet shopping will incrementally influence

the performance of purchasing and information

searching (Chen et al., 2002). Based on previous

studies, we propose:

H14: The usefulness of Internet shopping

positively influences a customer’s attitude toward

using it.

H15: The usefulness of Internet shopping

positively influences a customer’s behavioral

intention on using it.

Service quality: The discrepancy between what

customers expect and what customers obtain. Since

offline Japanese customers significantly consider

getting high-quality products and services, the

service quality of products and services in Japan is

regularly high (Synodinos, 2001). This is also a

necessary concern in Internet shopping to provide

the high service quality to online customers in Japan.

This leads to the hypothesis:

H16: The service quality of Internet shopping

positively influences a customer’s attitude toward

using it.

Usability of Internet shopping website: The

degree to which Internet shopping would be easily

and quickly used by customers to navigate, operate

and find what they want. Many Japanese have

comparatively little free time (Synodinos, 2001). If

Internet shopping can provide customers with time-

saving shopping, the usability of an Internet

shopping website may influence the ease of use

CRITICAL SUCCESS FACTORS OF INTERNET SHOPPING IN JAPAN: CUSTOMER-CENTRIC AND

WEBSITE-CENTRIC PERSPECTIVES

263

factor, which directly affects customers’ attitudes

toward purchasing items through the Internet.

H17: Usability of Internet shopping websites

positively influences the ease of use of Internet

shopping.

Information richness: The degree to which

customers can use the information to predict their

satisfaction levels with the product prior to the

actual purchase. Japanese may expect a lot of

product information and product comparison

functions as useful because they have been

characterized as insatiable information seekers

(Synodinos, 2001). Thus, the information richness

may influence the usefulness of Internet shopping,

which directly relates to a customer’s attitude toward

using Internet shopping. Another hypothesis is:

H18: The information richness of Internet

shopping positively influences the usefulness of

Internet shopping.

Product offering: The abundance of different

products, pricing strategies, and product retail

channel fits. Previous studies found that the

usefulness of Internet shopping is determined by the

product offerings (Chen et al., 2004). In addition,

since the cheap prices and rare products provided as

product offering of Internet shopping make Japanese

customers shop online (Atchariyachanvanich and

Okada, 2006b), product offerings may influence a

customer’s attitude toward using it. Thus, we

propose:

H19: The product offering of Internet shopping

positively influences the usefulness of Internet

shopping.

H20: The product offering of Internet shopping

positively influences a customer’s attitude toward

using it.

The last two hypotheses were in line with

previous studies.

H21: A customer’s attitude toward using Internet

shopping positively influences her or her behavioral

intention to use it.

H22: A customer’s behavioral intention to use

Internet shopping positively influences his or her

actual use of it.

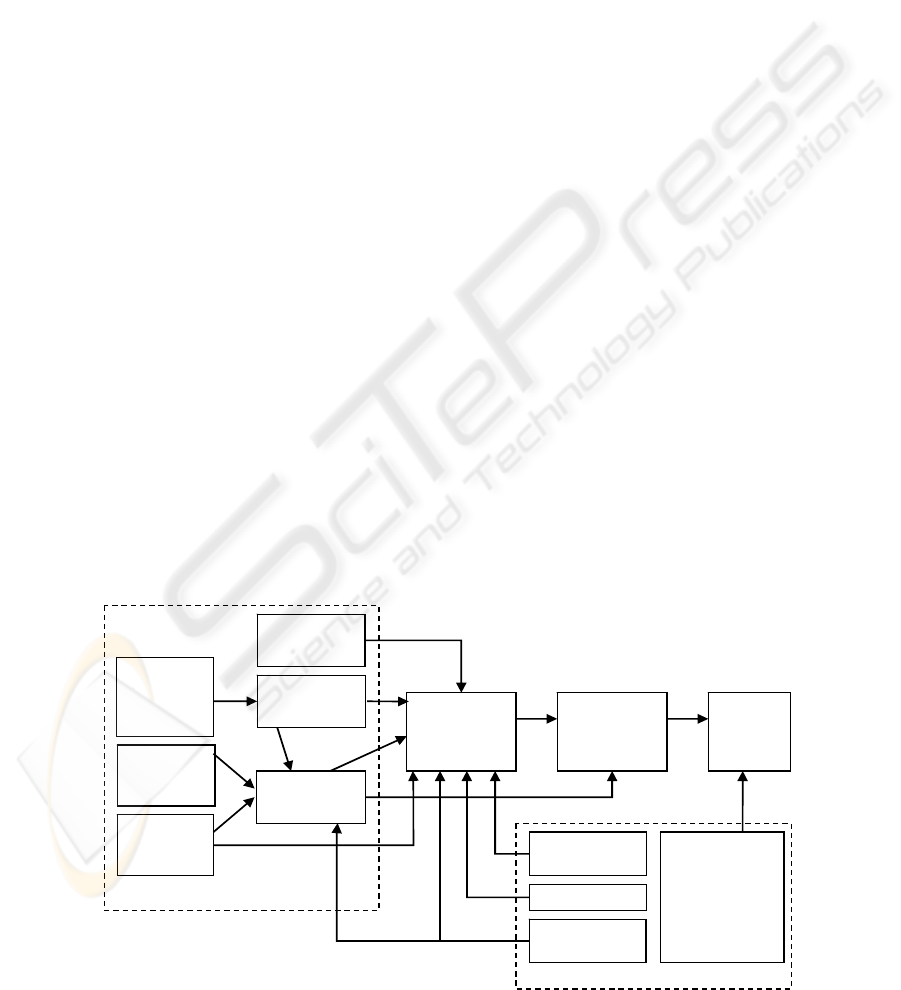

3 RESEARCH MODEL

The research model used the consumers’ acceptance

of virtual stores model developed by Chen et al.

(2004) to investigate the factors affecting the

Internet shopping in Japan and to study the effects of

customer characteristics on the actual use of it. The

research model consists of thirteen constructs; ten

critical success factors and three determinants of the

actual use of Internet shopping. Figure 1 shows two

groups of critical success factors and their proposed

relations. A new factor, need specificity, was added

to the base model and critical success factors that

were investigated were categorized into two groups:

customer-centric/website-centric- perspectives.

3.1 Data Collection

A web-based survey was conducted to investigate

the critical success factors and consumer purchasing

behaviour through the Internet. The online

questionnaire consisted of two sections. The first

section was designed to gather the demographic

characteristics including age, gender, monthly

personal income, and Internet activities. In the

second section, the constructs employed in the

model were measured using multi-item scales. Each

construct contains several items measured by the

fully anchored, 5-point Likert scale ranging from (1)

“strongly disagree” to (5) “strongly agree”. The

items were generated from previous research

projects and were modified to fit the context of

Internet shopping when necessary.

As the survey was conducted in Japan, a

Japanese version of the questionnaire was

administrated. The questionnaire, originally written

in English, was translated into Japanese by bilingual

people whose native language was Japanese and

whose background was IT-oriented. The

questionnaire was then translated back into English

by other bilingual people whose native language was

English and whose background was also IT-oriented.

The English versions were then compared, and no

item was found to pertain to a specific cultural

context in terms of language or to a specific IT-

related context in terms of background translation.

An online survey targeted at potential online users

who have purchased a product or service through

Internet shopping was utilized to collect data. All

questions were posted on a reliable website with

four million registered users operated by the goo

Research of NTT Resonant Inc. in Japan

(www.goo.ne.jp). The period of the questionnaire

ran from July 21 to 25, 2006. After the initial

reliability and validity screening, 1,215 responses

were found to be complete and usable.

The initial screening eliminated incomplete and

fictional responses. Among the 1,215 respondents,

the percentages of gender (51.3%, 48.7% were male

and female respectively) and age group (7.4%,

19.5%, 22.1%, 18.4%, 18.8%, and 13.8% were aged

between 15-19, 20-29, 30-39, 40-49, 50-59, and

more than 60 respectively), which are the same

percentages as those from the communication usage

ICE-B 2007 - International Conference on e-Business

264

trend survey conducted in 2005 by the Ministry of

Internal Affairs and Communications (2006).

Therefore, the results of our study predicted the

same trend as the ministry’s study of online

customers in Japan does.

3.2 Data Analysis

The data analysis employed a two-step approach

Anderson and Gerbing, 1988) using a statistical

program, SPSS, and a covariance-based program,

AMOS. In the first step, the measurement model

was examined for instrument validity and refinement

by using a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). The

second step involved confirming the relationships

and testing the hypotheses of the research model by

using the structural equation modeling (SEM)

technique.

To test the reliability of the initial questionnaire,

a Cronbach alpha was calculated for each construct

and the results are presented in Table 1.

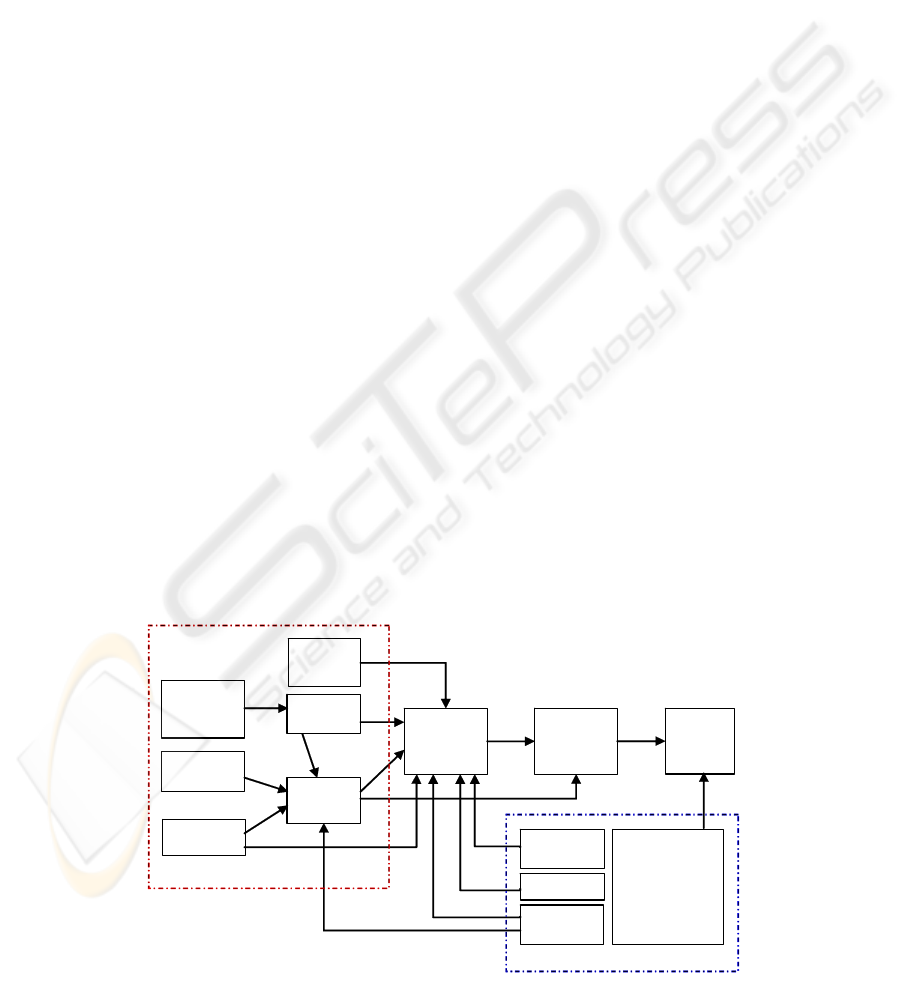

The test of the structural model estimated the

goodness-of-fit of the research models so that the

hypothesized model would be a good representation

of the structures underlying the observed data. The

chi-square of the revised model was calculated to be

4015.213 (p=0.0) with 866 degrees of freedom. The

root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA)

was 0.055, which indicates a good fit and reasonable

errors of approximation in the population and was

lower than the recommended limit of 0.08 [23]. The

0.033 root mean square residual (RMR) and the

0.904 comparative fit index (CFI) meet the

recommended levels of 0.05 and 0.90, respectively

(Byrne, 2001). Overall, the research model for the

customer intention to purchase through the Internet

appears to be statistically well fitting. Figure 2

shows the results of the structural paths of the

research model. The estimated path effects

(standardized) are presented.

4 RESULTS

4.1 Customer-Centric Perspective

4.1.1 Customer’s Characteristics

The actual use of Internet shopping was measured

by a number of purchases that was defined as how

many times online customers have purchased items

through Internet shopping in the last six months. The

customer characteristic distributions of the

responding sample and the mean number of

purchases toward using Internet shopping are shown

in Table 2.

The percentage of respondents within each

characteristic distribution is enclosed in parentheses.

T-tests for independent samples were used to

identify the response differences in the actual use of

Internet shopping per gender and marital status.

An analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to

determine the response differences in actual Internet

shopping use based on age group, income, and levels

of education, innovativeness, and net-orientation. In

addition, regression analysis was used to indicate

how a change in each independent variable (age

group, income, education level, innovativeness, and

net-orientation) affects the values taken by the

dependent variable.

Information

Richness

(IR)

Product

Offerings

(PO)

Usefulness

(U)

Ease of Use

(EOU)

Compatibility

(C)

Service

Quality (SQ)

Trust

(

T

)

Attitude

toward Using

Internet

Shopping (A)

Behavioral

Intention to

Use Internet

Shopping (BI)

Actual

Use of

Internet

Shopping

Need

Specificity (N)

Characteristics

Age

Gender

Marital status

Education

Income

Innovativeness

Net-orientation

Web-centric perspective

Customer-centric perspective

Usability of

Internet

Shopping

Website (U)

H1-H7

H16

H8

H9

H10

H11

H13

H12

H14

H15

H17

H18

H19

H20

H21 H22

Figure 1: Research model.

CRITICAL SUCCESS FACTORS OF INTERNET SHOPPING IN JAPAN: CUSTOMER-CENTRIC AND

WEBSITE-CENTRIC PERSPECTIVES

265

Table 1: Reliability of measured constructs.

Constructs

No. of initial

questions

No. of final

questions

Cronbach

alpha

Actual Use of Internet

Shopping

2 2 0.661

Behavioral Intention to

Use Internet Shopping

(BI)

1 1 1.000

Attitude toward Using

Internet Shopping (A)

3 3 0.898

Perceived Usefulness

5 5 0.883

Perceived Ease of Use

4 4 0.916

Compatibility (C) 3 2 0.797

Need Specificity (N) 3 2 0.418

Perceived Service

Q

ualit

y

(

S

Q)

10 9 0.906

Perceived Trust (T) 6 6 0.899

Product Offerings (PO) 5 4 0.779

Information Richness

5 3 0.715

Usability of Internet

Shopping Website (U)

5 2 0.801

The T-test results for the independent samples

showed that a number of purchases toward using

Internet shopping show an insignificant difference

per age group, marital status, and income. Therefore,

H1, H3, and H4 were rejected.

Gender was found to significantly affect the

actual use of Internet shopping. Female customers

made significantly more purchases (mean score of

6.87) than male customers did. Thus, H2 was

rejected. Concerning the customer’s education level,

the number of purchases were found to be

significantly different (F = 4.476, df = 7, sig. =

0.035). The regression analysis results showed that

the customer’s education level positively affected

the number of purchases made (β = 0.32, t = 2.12),

supporting H5. Customers who hold doctoral

degrees made the most purchases. Unexpectedly,

customers with the lowest level of education made a

rather high number of purchases.

The results showed that high-innovative customers

made the highest number of purchases (mean score

of 7.25) than other groups of innovative customers.

In other words, high-innovative customers tend to

more frequently purchase items through the Internet

than low-innovative customers. The regression

analysis results showed that innovativeness

positively affects the number of purchases (β = 1.30,

t = 3.47), thus supporting H6. High-net-oriented

customers made the highest number of purchases

(mean score of 7.88) than other groups of net-

oriented customers. The regression analysis results

showed that net-oriented positively affects the

number of purchases (β = 2.48, t = 6.32), thus

supporting H7.

Table 2: Customer characteristics and mean number of

purchases.

Characteristics Number (Percent) Mean

Age group: (F= 0.072, Sig.= 0.788)

15-19 90 (7) 4.17

20-29 238 (20) 6.11

30-39 268 (22) 7.29

40-49 223 (18) 7.30

50-59 228 (19) 5.87

>=60 168 (14) 5.67

Gender: (F= 5.551, Sig.= 0.019*)

Male 624 (51) 5.84

Female 591 (49) 6.87

Marital Status: (F= 0.048, Sig.= 0.589)

Single 461 (38) 6.49

Married 754 (62) 6.25

Income: (F= 3.127, Sig.= 0.077)

< 250,000 JPY 214 (18) 5.91

250,000 – 499,999 422 (35) 6.14

500,000 – 749,999 230 (19) 6.74

> 750,000 JPY 176 (14) 6.99

Education Level: (F= 4.476, Sig.= 0.035*)

Secondary School 30 (2) 7.43

High School 357 (29) 5.64

Vocational School 128 (11) 6.22

College 131 (11) 5.87

Bachelor Degree 493 (41) 6.80

Master Degree 65 (5) 6.62

Doctoral Degree 11 (1) 10.82

Innovativeness: (F= 12.030, Sig.= 0.001***)

Low 75 (6) 4.72

Medium 684 (56) 5.91

High 456 (38) 7.25

Net-orientation: (F= 39.921, Sig.= 0.000***)

Low 38 (3) 3.61

Medium 652(54) 5.26

High 525 (43) 7.88

*, **, *** significance at p < 0.05, 0.01, and 0.001,

4.1.2 Need Specificity, Trust, and

Compatibility

Figure 2 illustrates the structural model results. It

supports the H11 hypothesis of the effect of need

specificity on a customer’s attitude toward using

Internet shopping. However, H8 and H9 were

rejected. These results indicated that customers’

ICE-B 2007 - International Conference on e-Business

266

subjective reasons in trusting Internet shopping and

compatible with Internet shopping would not affect

Internet shopping behavior.

4.2 Website-Centric Perspective

All website-centric perspective hypotheses (H12-

H20), except H20 concerning product offering were

valid after testing the research model. These results

indicated that the features of Internet shopping

including ease of use, usefulness, usability of

Internet shopping website, and information richness

affected a customer’ attitude toward using Internet

shopping and indirectly influenced the actual use of

it. Surprisingly, the service quality of Internet

shopping was found to have a negative impact on a

customer’s attitude toward using Internet shopping.

However, its coefficient and significance level are

low enough to be considered insignificant. Thus, this

implies that the service quality of Internet shopping

has no effect on Internet shopping behavior.

Moreover, product offering has no direct impact on

the customer’s attitude toward using Internet

shopping.

5 CONCLUSION

This study was conducted to explore the critical

success factors in terms of customer-centric and

website-centric perspectives that influence a

Japanese customer to use Internet shopping. The

consumer acceptance of virtual stores developed by

Chen et al. (2004) was used as a base model to test

the research hypotheses. From an online survey,

educated females with high incomes and low

innovative Japanese are the most active online

customers.

The critical success factors have been grouped

into two categories, (a) customer-centric

perspectives helping managerial people understand

the nature of consumer behaviors and (b) website-

centric perspectives providing insights into the

features and elements of Internet shopping websites

that make customers purchase items through Internet

shopping.

Regarding the customer characteristics as

customer-centric factors, an interesting find was that

the more innovative the online customers are, the

less intent they are on purchasing items through the

Internet. This finding does not conform to those of

previous studies (Limayem et al., 2000; Blake et al.,

2003). Since their respondents were not Japanese,

one possible reason to explain this is that the

consumption behavior of our respondents, which

were Japanese, is notably different from those of

other societies (Synodinos, 2001). Consequently, it

implies that the effect of innovativeness on the

actual use of Internet shopping may depend on the

nationality of the respondents. Unexpectedly, trust

has no impact on the customer behavior of Internet

shopping. This may be because of our limitation on

the respondents, who were members of the goo

website. Their perception of trust in Internet

shopping had already been approved and become

insignificant to their attitude toward using Internet

shopping. Regarding the insignificance of

compatibility, it may be because the underlying

items of compatibility made Japanese respondents

reluctant to answer with their true feeling on

whether purchasing items through Internet shopping

matched their needs. This issue should be considered

for further study.

0.42***

Behavioral

Intention to

Use Internet

Shopping (BI)

Attitude

toward Using

Internet

Shopping (A)

0.14***

Service

Quality

(SQ)

Actual Use

of Internet

Shopping

Characteristics:

Age

Gender

Marital status

Education

Income

Innovativeness

Net-orientation

Customer-centric perspective

Website-centric perspective

0.65***

0.3***

Product

Offerings (PO)

Need

Specificity (N)

Trust (T)

Compatibility

(C)

Usefulness

(U)

Ease of Use

(EOU)

-0.13

*

0.16***

0.65***

0.15***

0.64***

0.59***

0.05

ns

-0.16

ns

0.04

ns

-0.11

ns

***, **, * Significant at the 0.001 level, 0.01, and 0.05 level respectively.

ns

Not significant at the 0.05 level.

Usability of

Internet

Shopping

Website (U)

Information

Richness (IR)

0.5***

Figure 2: Model Results.

CRITICAL SUCCESS FACTORS OF INTERNET SHOPPING IN JAPAN: CUSTOMER-CENTRIC AND

WEBSITE-CENTRIC PERSPECTIVES

267

The findings showed that the website-centric

perspective factors have played a more important

role than those of the customer-centric perspective

factors. This indicated that enhancing the EC

website can ensure the success of EC, because the

website-centric perspective factors are more

controllable than the customer-centric perspective

factors. In addition, Japanese online customers do

not consider the service quality of Internet shopping

as importantly as Japanese offline customers.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research is a part of the Digital Eizou Common

Specification Development Project (DECSDP) and

was supported by the Science and Technology

Promotion Adjustment Budget of the Ministry of

Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology,

Japan.

REFERENCES

Anderson, J. C., and Gerbing, D. W., 1988. Structural

equation modeling in practice: a review and

recommended two-step approach. Psychological

Bulletin, (103:3), 411-423.

Atchariyachanvanich, K. and Okada, H., 2006a. An

empirical study on factors affecting the success and

growth of electronic commerce. In Proceedings of the

13th European Conference on Information Technology

Evaluation, University of Genoa, Italy, September 28-

29, 2006, 31-40.

Atchariyachanvanich, K. and Okada, H., 2006b. A study

on factors affecting the purchasing process of online

shopping: a survey in China & Japan. In Proceedings

of the 7th Asia Pacific Industrial Engineering and

Management Systems Conference 2006, Bangkok,

Thailand, December 17-20, 2006, 2279-2286.

Bellman, S., Lohse, G. L., and Johnson, E. J., 2000.

Predictors of online buying behavior. Communications

of the ACM, 42 (12), 32-38.

Bhatnagar, A. and Sanjoy, G., 2004. Segmenting

consumers based on the benefits and risks of internet

shopping. Journal of Business Research, 57, 1352-1360.

Blake, B. F., Neuendorf, K. A., and Valdiserri, C. M.,

2003. Innovativeness and variety of internet shopping.

Internet Research: Electronic Networking

Applications and Policy, 13 (3), 156-169.

Byrne, M. B. 2001. Structural Equation Modeling with

AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and

Programming, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc.,

New Jersey.

Cao, X. and Mokhtarian, P. L., 2005. The intended and

actual adoption of online purchasing: a brief review of

recent literature. Institute of Transportation Studies,

University of California, Davis, Research Report

UCD-ITS-RR-05-07; http://pubs.its.ucdavis.edu/

publication_detail.php?id=49 (June 17, 2006).

Chen, L. D., Gillenson, M. L., and Sherrell, D. L., 2002.

Enticing online consumers: an extended technology

acceptance perspective. Information & Management,

39, 705-719.

Chen, L., Gillenson, M.L., and Sherrell, D.L., 2004.

Consumer acceptance of virtual stores: a theoretical

model and critical success factors for virtual stores.

ACM SIGMIS Database, Vol. 35, No. 2, 8-31.

Hoffman, D. L., Novak, T. P., and Peralta, M., 1999.

Building consumer trust online. Communications of

the ACM, 42 (4), 82-85.

International Data Corporation, 2004. Internet Commerce

Market Model, version 9.1, International Data

Corporation, Framingham, MA.

Koufaris, M., Kambil, A., and LaBarbera, P. A., 2001.

Consumer behavior in Web-based commerce: an

empirical study. International Journal of Electronic

Commerce, Vol. 6, No. 2, 115-138.

Koyuncu, C. and Bhattacharya, G. 2004. The impacts of

quickness, price, payment risk, and delivery issues on

on-line shopping. Journal of Socio-Economics, 33, 241-

251.

Kwong, et al., 2002. Online consumer behavior: an

overview and analysis of the literature. In Proceedings

of the Six Pacific Asia Conference on Information

System, Tokyo, Japan, September 2-4, 2002, 813-827.

Limayem, M., Khalifa, M. and Frini, A., 2000. What

makes consumers buy from Internet? A longitudinal

study of online shopping.

IEEE Transaction on

Systems, Man, and Cybernetics-Part A: A Systems and

Humans, Vol. 30, No. 4, 421-432.

MacCallum, R. C., Browne, M. W., and Sugawara, H. M.,

1996. Power analysis and determination of sample size

for covariance structure modelling. Psychological

Methods, (1:2), 130-149.

Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, 2006.

Communications usage trend survey in 2005.

Telecommunications Bureau, Ministry of Internal

Affairs and Communications, Tokyo, Japan.

Pavlou, P. A., 2003. Consumer acceptance of electronic

commerce: integrating trust and risk with the

technology acceptance model. International Journal of

Electronic Commerce, Vol. 7, No. 3, l0l-134.

Raijas, A. and Tuunainen, V. K., 2001. Critical factors in

electronic grocery shopping. International Review of

Retail Distribution and Consumer Research, 11 (3),

255–265.

Slyke, C. V., Comunale, C. L., and Belanger, F., 2002.

Gender differences in perceptions of web-based

shopping. Communications of the ACM, 45 (7), 82-86.

Synodinos, N. E., 2001. Understanding Japanese

consumers: some important underlying factors.

Japanese Psychological Research, Vol. 43, No. 4,

2001, 235-248.

Turban et al., 2002. Electronic Commerce 2002: A

Managerial Perspective, Prentice-Hall, New Jersey.

Verhoef, P. C. and Langerak, F., 2001. Possible

determinants of consumers' adoption of electronic

grocery shopping in the Netherlands. Journal of

Retailing and Consumer Services, 8, 275-285.

Yang, K. C. C., 2005. Exploring factors affecting the

adoption of mobile commerce in Singapore.

Telemetics and Informatics, 22, 257-277.

ICE-B 2007 - International Conference on e-Business

268