IMPACTS OF E-LEARNING ON ORGANISATIONAL

STRATEGY

Charles A. Shoniregun, Paul Smith

School of Computing and Technology,

University of East London

Longbridge Road,

Barking Campus,

Dagenham Essex,

RM8 2AS, UK

Alex Logvynovskiy

Business, Computing and Information Management,

London South Bank University

Borough Road,

SE1 0AA, UK.

Vyacheslav Grebenyuk

Centre of Technologies for Distant Education,

Virtual & Distant Learning Lab

Kharkov National University of Radioelectronics,

14 Lenin Av.,

Kharkov 61166,

Ukraine

Keywords: e-learning, eCRM, security.

Abstract: E-learning is a relatively new concept. It has been developed to describe the convergence of a whole range

of learning tools, which use technology as their basis for delivery. E-learning is using technology to assist in

delivering learning experiences to learners. It is also a concept which is built around the philosophy of

“anytime and anywhere” learning meaning that learners can access learning materials when and as required,

no matter where they happen to be located in the world or, indeed, off world. E-learning gives both strategic

and competitive advantage to organisations. Business organisations recognised knowledge and people are

critical resources that should be treated as treasures. In the information ages the speed of introducing new

products, and services, requires employees to learn and consolidate new information quickly and effec-

tively. This paper discusses the factors that impact the organisational e-learning and advocates the strategic

context. We also conducted questionnaire survey to show the factors that impact organisational e-learning.

The question posed by this paper is that: ‘Can organisation develop an e-learning strategy that encompasses

the impacts of organisational strategic context?’

1 INTRODUCTION

Organisational culture is critical to the fruitful incep-

tion, growth and success of e-learning in any organi-

sation. Kotter and Hesket (1992) related that it is

helpful to think of organisational culture as having

two levels that differ in terms of their visibility and

their resistance to change. At the deeper and less

visible level, culture refers to values that are shared

by people in a group and that tend to persist over

time even when group membership changes. At the

more visible level, culture represents the behaviour

474

A. Shoniregun C., Smith P., Logvynovskiy A. and Grebenyuk V. (2005).

IMPACTS OF E-LEARNING ON ORGANISATIONAL STRATEGY.

In Proceedings of the First International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies, pages 474-481

DOI: 10.5220/0001227004740481

Copyright

c

SciTePress

patterns or style of an organisation that employees

are automatically encouraged to follow by their fel-

low employees. Nahavandi and Malekzadeh (1993)

discussed assumptions as being the third level of

culture, which is composed of basic assumptions

resulting from an organisation’s success and failures

in dealing with the environment. These assumptions

encompass an organisation’s basic philosophy and

worldview, and they shape the way the environment

and all other events are perceived and interpreted.

Values, behaviour and assumptions combined with

organisational leadership nurture the bond and iden-

tity that unites the members of organisations. Organ-

isational culture places high value on information

possession and control. Some organisations found

the basic nature of the intranet is in direct conflict

with their basic training. Huseman and Goodman,

(1999) stated that the path to becoming a knowledge

organisation is not easy. It requires new types of

investments, new systems and viewing employees

and customers differently. Khajanchi and Kanfer

(2000) recognised that every organisation may have

a unique solution for learning development but this

depend on skill requirements; thus, the following are

some of findings:

• Xerox used a “people driven” approach in design-

ing its systems.

• The users of Eureka at Xerox were recognised for

authoring and validating useful repair tips.

• HP gave away airline miles for contributions to

its Trainer’s Trading Post.

• Sun gave rewards and recognitions to encourage

sharing. The company wants to make knowledge

sharing a part of the annual review of the employ-

ees.

• Ernst & Young’s senior management provided

strong support for knowledge management as a

key competitive advantage. Consultants were

evaluated in part on their knowledge sharing.

The arrival of the Internet is a disruptive technol-

ogy for the training profession. Existing models will

be overturned; many trainers will resist. The losers

in the profession will be those who, through cultural

inertia, remain inside their own comfort zone and

think in terms of traditional models. A starting point

should be to look outside and see what can be

learned from analysis of the impact of the Internet on

business and economic activities of organisations.

2 RELATED WORK

The ‘e’ prefix is being attached to everything, such

as e-commerce and e-recruitment, and the latest in

the ‘e’ stable is e-learning. Different people mean

different things by the term ‘e-learning’. Most use

the term to refer to the provision of learning oppor-

tunities in various shapes and forms rather than the

process of learning itself (

Rosenberg, 2001). Zahm

(2000) described computer-based training (CBT) as

usually delivered via CD-ROM or as a Web

download and that it is usually multimedia-based

training. Karon (2000) discussed the convenience

factor of well-designed computer-based training by

saying that any well-designed computer-based train-

ing- whether it’s networked based or delivered via

the Internet – is more convenient than traditional

instructor-led training or seminars. The self-paced

CBT courses are available when learners are ready

to take them, not just when the seminar is scheduled

or the instructor is available. Hall (1997) incorpo-

rated both Zahm (2000) and Karon (2000) defini-

tions by underlining computer-based training as an

all-encompassing term used to describe any com-

puter-delivered training including CD-ROM and

World Wide Web (

Galagan, 2000). Hall and Snider

(2000) further explained that some people use the

term CBT to refer only to old-time, text-only train-

ing. Like CBT, online training was classified as an

all-encompassing term that refers to all training done

with a computer over a network, including a com-

pany’s intranet, the company’s local area network,

and the Internet. Gotschall (2000) states that the

online training is also known as net-based training

while Urdan and Weggen (2000), suggests that

online learning constitutes just one part of e-learning

and describes learning via Internet, intranet and ex-

tranet. Since the levels of sophistication of online

learning vary, it can extend from a basic online

learning program that includes text and graphics of

the course, exercises, testing, and record keeping,

such as test scores and bookmarks to a sophisticated

online learning program. Sophistication would in-

clude animations, simulations, audio and video se-

quences peer and expert discussion groups, online

mentoring, links to materials on corporate intranet or

the web, and communications with corporate educa-

tion records. Cases of e-learning are becoming part

of organisations daily life. The following are some of

the notable cases:

Case 1:

In 1996 Nancy Lewis, Director of IBM Management

Development, began to develop IBM’s global man-

agement training program. Recognising that more

than one session was needed-but that bringing to-

gether 5000 people from around the world was

costly and time-consuming; IBM looked at e-

learning. The goal was to find appropriate technol-

ogy to support different parts of the manager training

IMPACTS OF E-LEARNING ON ORGANISATIONAL STRATEGY

475

process-and engage and teach people who were used

to face-to-face training. The IBM’s Basic Blue e-

learning initiative brings training to more than 5000

IBM managers annually (

Webster and Hackley, 1997).

Basic Blue for managers, now an IBM Mindspan

solution, enables IBM to train managers to lead

high-performance teams-without the expense of on-

site meetings and travel. Key benefits Nucleus meas-

ured in calculating the ROI from the solution include

the following:

• Direct savings such as reduced program, travel,

manager off-site costs and teacher expenses along

with other direct savings.

• Reduced the direct cost of content development.

• Indirect savings in the form of increased manager

productivity and saved employee time.

Using a blended approach of e-learning, elec-

tronic community, coaching, and simulation, IBM

was able to not only reduce costs by moving training

to the e-learning, but also take advantage of the

flexibility of the electronic medium to provide a

richer learning environment for their staff. The man-

agement-training program includes a web-based

learning infrastructure, virtual collaborative tools,

content references, and interactive online simulators

to complement face-to-face instruction. Managers

participate in 26 weeks of self-paced on-line learning

delivered through Lotus Learning Space modules. As

part of IBM’s ongoing management development

program, IBM trains more than 5000 new managers

each year. Traditionally, managers were brought

together for a 5-day event to learn the basics on IBM

culture, strategy, and management. As the complex-

ity of their jobs increased, IBM recognised that five

days was not enough time to train managers effec-

tively-and that to help managers evolve with the in-

dustry, training needed to be a ongoing process in-

stead of a one-time event.

Case 2:

For some time, training professionals working for

British Airways have been considering the issues

involved in time and space to learn. British Airways

does not claim to have solved the issues involved in

time and space to learn and is currently re-orienting

and redesigning its approach.

In 1997, British Airways moved its corporate

headquarters to a new building, Waterside. Some

2,500 employees would be located at this new pur-

pose-built site. All would access to training and to be

able to participate in other communication activities

built on new technologies. There are technology-

based activities to deliver: a discrete designated

workstation in an office area, individual desktops

using CD-ROMs, and individual desktops via the

local area network. Particularly important were those

that used video, including desktop video conferenc-

ing, stored videos, and British Airways TV. It is es-

tablished as “QUEST and Communication Points”.

Forty-five separate QUEST and communication

points were installed. Each contained a high-

specification PC that was branded to distinguish it

from other desktop PCs.

In March 1999, a review showed that training was

the most accessed resource at the QUEST and com-

munication points. The usage statistics highlighted

the fact that the points were most used in the areas

that had promoted their use and had requested addi-

tional coaching. The British Airways training team

summed up the situation as follows: we will use the

knowledge gained from the trials and implementa-

tion of the points to shape our future e-learning strat-

egy. At the same time, some difficulties were identi-

fied. Currently, British Airways is re-launching the

initiative, which will now be firmly owned by the

training function.

3 E-LEARNING CHALLENGES

Learning is psychological and it does not matter

whether we learn at school or in an organisation not

everyone learn at the same pace because of our indi-

viduality. Hayes (1984) states that learning is a rela-

tively permanent change in behaviour, which occurs

as a result of experience. It is not possible to see

what people learn. However, this can be display in

their behaviour. Therefore e-learning challenges the

user to their full potential, because learning can be

access whenever the learner chooses. But the way in

which organisations learn is different compare to the

traditional classroom method of learning which re-

quire an instructor, a classroom and other resources

and materials. Due to the rapid changes in world

economy, there is a need for organisations to provide

‘just-in-time’ and ‘just-enough’ learning to facilitate

the management of change and hence create com-

petitive advantage. Therefore organisations are able

to take advantage of new learning technologies,

which will provide the necessary benefits need to

steer the business into the right strategic direction to

beat off tough competition.

Given the broad definition of online training, it

would seem safe to assume that web-based training

is online training. Hall (1997) defined web-based

training as instruction that is delivered over the

Internet or over a company’s intranet. Accessibility

of this training, related Hall, is through the use of a

web-browser such as Netscape Navigator. Hall and

Snider (2000) define e-learning as the process of

learning via computers over the Internet and intra-

WEBIST 2005 - E-LEARNING

476

nets. They extended that e-learning is also referred to

as web-based training, online training, distributed

learning or technology for learning. Distance learn-

ing was not included in the e-learning definition and

was defined as its own entity as a learning process

meeting three criteria: a geographical distance sepa-

rates communication between the trainer and partici-

pant; the communication is two way and interactive;

and some form technology is used to facilitate the

learning process.

The context in which organisation operates inter-

nal and external training, and the role of the trainer

would be expected to undergo profound changes.

For an organisation operating in global marketplace,

training is essential to drive the organisation through

turbulence competition, from home markets and

other global competitors. The greatest success for e-

learning within the professional and corporate seg-

ments is to deliver specific users the training that can

enable them to achieve high rewards and greater

credential. The rapid developments in both hardware

and software have given the trainer the potential of

having new information technology tools to assist in

the delivery of e-learning. The competition in the

modern age, therefore, is not about metal bashing or

seeking to be the lowest-cost producer; it is about

harnessing the creative talents in the organisation to

bring value to existing and future customers.

Organisations invest on continuously upgrading

its labour, share and store knowledge for competi-

tion and strategic advantage. They encourage their

staff to learn and manage the knowledge that has

been gained as a treasury. The learning organisation

is based on the notions that ‘learn for improvement’.

Organisation learning is an overall employee’s ac-

tivities and may also involve external stakeholder.

Market orientation, entrepreneurship, facilitative

leadership, organic and open structure, and a decen-

tralised planning are the five critical components of

learning organisation that have a synergistic influ-

ence on learning, which can potentially lead to com-

petitive advantage while adaptive learning inhibits

innovation. To practice learning, an organisation

(e.g. government departments, companies or aca-

demic institutions) needs to be skilled at systematic

problem solving, experimentation, learning from past

experience, learning from others, and transferring

knowledge.

3.1 Managing and Sharing Knowledge

The knowledge management enabled organisation to

managed and shared the knowledge with the help of

technologies. Filtering knowledge, strengthening

corporate philosophy and culture, and facilitating

communication are the three strategies for managing

and sharing knowledge:

i. Filtering knowledge: Not all knowledge as the

same value, so the identification of knowledge

from information and data is useful in knowledge

management. Too much information will lead to

over look key information and under-evaluate in-

formation. By setting up cross-divisional review-

ing teams, the value of knowledge can be filtered

and made available to various departments within

the organisation. The effective filtering knowl-

edge requires hybrid of human and technological

resource. However, computer and communication

systems are good at capturing, transformation,

and distribution of highly structured knowledge

that changes rapidly. On the other hand, human is

good at performing task such as interpreting

knowledge within a broader context, to combine

knowledge with other types of information, and to

synthesise various unstructured form of knowl-

edge.

ii. Strengthening corporate philosophy and culture:

Organisation should build an environment that re-

spect individuals and encourages individual crea-

tivity for effective knowledge sharing and man-

agement. Strengthening organisation culture cre-

ates climate that fosters long-lived trusting rela-

tionship and proactive knowledge sharing within

the organisation.

iii. Facilitating communication: Effective and effi-

cient communication can help knowledge spread

quickly and throughout the organisation. In other

to effectively share knowledge across the organi-

sation, organisation should focus on knowledge

flow (communication) rather than knowledge

store. Knowledge improved organisation’s ability

to make rapid decisions and execute them effec-

tively.

It is important to classify knowledge from infor-

mation and data to prevent waste of management

energy. The best use of knowledge is to innovate and

focus on the future. The activities of knowledge

management include capture, editing, packaging and

pruning, development, categorising, and distributing.

IMPACTS OF E-LEARNING ON ORGANISATIONAL STRATEGY

477

4 STRATEGIC CONTEXT OF E-

LEARNING

The strategic context of e-learning, in terms of cost,

buying off-the-shelf materials is probably the least

cost option and this is currently the predominant

provision of e-learning. There are a considerable

number of off-the-shelf programmes available on the

market with many companies offering a trial period

before buying. The majority of packages are aimed

at developing IT skills, for example the Microsoft

certification. Whilst training for skills such as IT

may be generic, organisations of all sizes still have

their individual training needs and the content of an

off-the-shelf programme may not be appropriate nor

offer the required level of support. It may also be

difficult to assess the quality of a programme prior to

commitment to purchase and so as has often hap-

pened, an e-learning programme could prove to be

boring and irrelevant with a high drop out rate. If an

e-learning programme is not delivering the required

training then it may be more cost effective, particu-

larly where large numbers are concerned, to pur-

chase a bespoke course. A bespoke course can focus

precisely on those topics relevant to the organisation

and be used many times without the cost of licence

fees. Rosenberg (2001) suggests three reasons why

outsourcing may be the most suitable strategy:

As technology is developing rapidly, it may be

costly to maintain state-of-the-art e-learning capacity

over a long period. By outsourcing, the organisation

therefore avoids the risks associated with emerging

technologies. A related issue is that of competency.

Whilst most organisations will have an IT depart-

ment, it will be more effective to allocate resources

to supporting the organisation’s strategy. External

providers will have the necessary expertise for de-

veloping the programme faster and they will also be

aware of recent developments.

Finally, there is capacity to consider. As the de-

mand for training fluctuates, outsourcing allows the

organisation to expand or reduce training without

affecting its own training department. It is necessary

to have a thorough understanding of what organisa-

tion and/or the academic institution need and also to

look for a vendor with a stable financial base.

Indeed, more and more programmes will be de-

veloped in-house as it can be argued that not only

does this keep down costs but it also allows the or-

ganisation and/or the academic institution to have

full control over the product including copyright.

This will enhanced the existing skills so that the fu-

Table 1: Factors that impact organisational strategic context of e-learning

250 Organisation responses

(n=250)

Criteria: Impacting factors with elements

Yes No

Management

• Customers

• Competition

• Government Policy

240

248

80

10

2

170

Application

• Skill Development (Training)

• KM (Knowledge Management)

• RD (Research And Development)

• Service Provider

250

180

230

200

0

70

20

50

Infrastructure

• Economics

• Technology

• Social Culture

• Ecology

200

250

190

180

50

0

60

70

Communication 250 0

WEBIST 2005 - E-LEARNING

478

ture development will become easier and the organi-

sation can carry out its own maintenance.

4.1 Impacting factors

We conducted a questionnaire survey to show the

impacting factors that impact organisational e-

learning strategy. The 250 organisations that partici-

pated in the investigation are among the leaders in

automobile, telecommucations, banking, travel and

leisure, and food-and-drink industries from Europe

and the USA. The detailed analyses of the factors

that impact organisational e-learning strategy within

these organisations was possible to be established

thought the completion of questionnaires. We used 4

criteria to measure the factors that impact organisa-

tional e-learning (see data generated from the survey

in Table 1).

Based on the responses in Table 1, an average of

208 out of 250 organisations (i.e. 83.2%) agreed on

the factors that impact organisational strategic con-

text of e-learning while only 42 of them (i.e. 16.8%)

disagreed.

4.2 Factors that impact organisational e-

learning

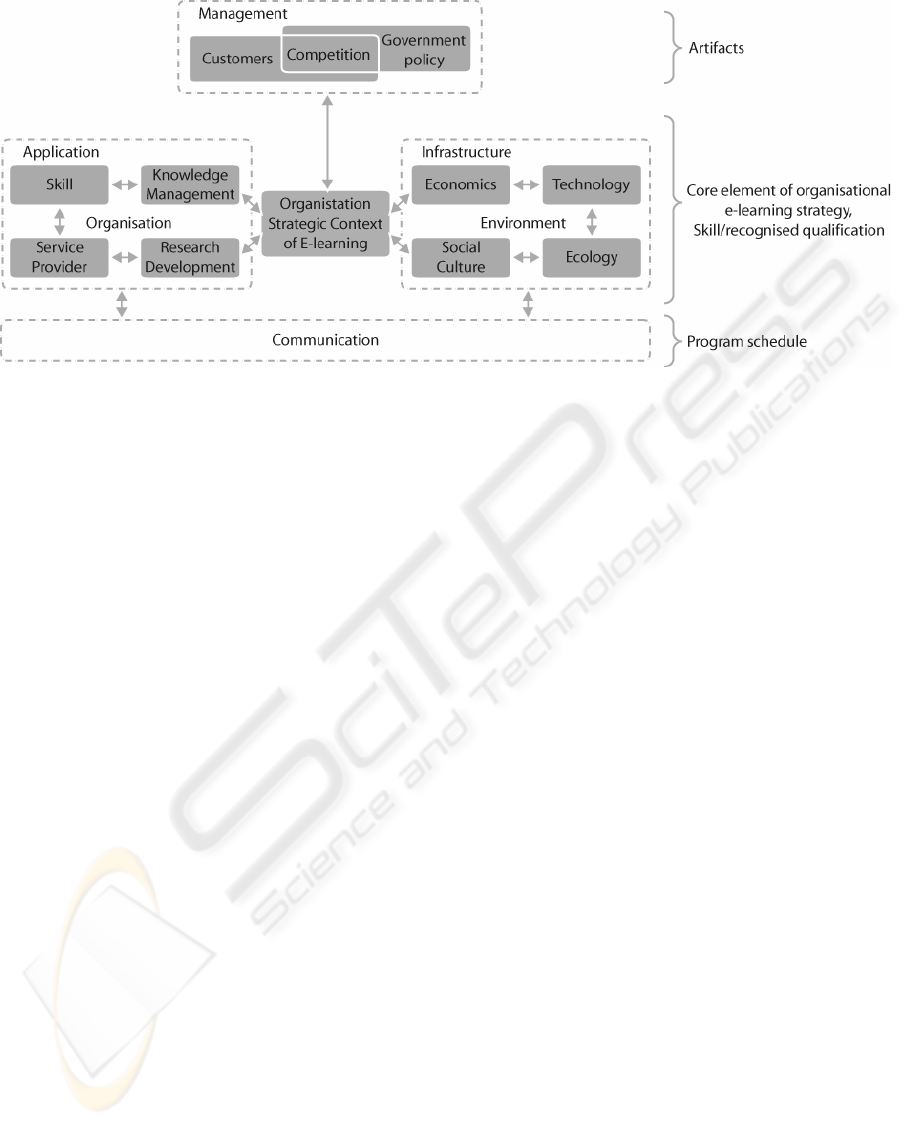

We have also used the criteria in Table 1 to present

the organisational strategic context of e-learning

model in Figure 1 which includes the elements

within individual factors. This model shows an itera-

tive process among artifacts, skill/recognised qualifi-

cation, core element of organisational e-learning

strategy and the program schedule. The following

are the factors that impact organisational e-learning:

1. Management. The management factor involved

customers, competition and government policy,

which are the elements that guide the organisation

to achieve desired goals. The management deals

with these factors in relation to the organisation

strategy.

2. Application: The application factor covers ele-

ments such as skills, knowledge management, re-

search development, and the service provider.

Theses elements involve the activities of develop-

ing, programming, implementing and using soft-

ware application that are used for organisations e-

learning or support e-learning activities. The ap-

plication factor addresses the ‘what’ and not

about the ‘how’ of software that is, questions like:

‘What skill do we need?’, ‘What information are

we going to manage within the knowledge man-

agement?’, ‘What are the requirements for the e-

learning application?’, ‘What are the research and

development required?’, ‘What service provider

to be used?’ The factor do not precisely deter-

mine to exact elements that raises the most am-

biguous questions: ‘What the e-learning applica-

tion is supposed to do?’ depends on the strategic

decision about ‘What is the skill area the organi-

sation actually wants to develop?’

3. Infrastructure: The infrastructure factor covers

elements such as the economics, technology, so-

cial culture and ecology. These elements are pre-

requisite of the environment that is beyond an or-

ganisation’s influence. The infrastructure of or-

ganisational strategic context of e-learning build

on an open stands, integrates into the existing in-

frastructure.

4. Communication: The communication factor deals

with issue of transmitting information.

Figure 1: Organisational strategic context of e-learning model

IMPACTS OF E-LEARNING ON ORGANISATIONAL STRATEGY

479

5 DISCUSSION

The dominant technology in most discussions of e-

learning is the Internet. It has advantages and disad-

vantages compared to other platforms such as CD-

ROM. As a result, the preferred platform differs

from one application to another. According to Den-

nis Quilter, chief executive of a training supplier, the

AdVal Group, “CD-ROM is mainly used now to

deliver video or for material with heavy animations”

(

Rosenberg, 2001). The advantages of the Internet

mostly relate to its real time nature. These include

the ability to continuously update and refresh materi-

als, and its ability to provide direct communication

with other people. However, in its current form, the

Internet has significant limitations due to connec-

tions. These include bandwidth, connectivity prob-

lems, and spatial inflexibility as a result of the re-

quirement for a phone line (although this may even-

tually be overcome by wireless technology).

It is widely believed that e-learning will bring an

industrial revolution to training and education. IDC

(2001), the market research company, forecast last

year that the global corporate e-learning market will

be worth $23 billion in 2003 although this may take

a year or two longer following the downturn in the

market due to the terrorist events of September 11,

2001. Sheila McGovern, an IDC analyst, forecasts

the market in Europe will grow by 46% in 2002 and

57% by the end of 2003. At present e-learning is

only a small part of the overall global training mar-

ket. The IT analysis group Gartner, forecasting a

wider increase in the market to rise to over $33 bil-

lion by 2005, which would make up almost one third

of overall global training market (

McGovern, 2002).

The pure cost savings of e-learning are compelling

for organisations and academia, compared to tradi-

tional training courses. Savings arise from less time

off work, lower travel cost, smaller hotel bills and

potentially more effective learning. IBM has re-

ported saving more than $80 million in travel and

housing expenses by adopting on-line learning

across its worldwide operations. Forrester (2000)

interviewed training managers and knowledge offi-

cers at 40 Global companies and discovered that all

but one already has on-line initiatives. Of those

companies, 67% identified cost saving as the main

reason for adopting e-learning programs. Whalen

and Wright (1999) found that while e-learning has

higher development cost, these are offset by lower

delivery cost. Also, the reduction in course delivery

time (course compression) was from 12 hours of

traditional instruction to 2.5 hours of e-learning. It

has the potential to deliver courses to a larger num-

ber of students as well. The amount of multimedia

content was also a significant factor in terms of cost

savings. The study showed an average savings per

student ranging from $702 to $1,103, depending on

the level of multimedia.

6 CONCLUSION

Indeed, learning is becoming more, user friendly day

by day and the need to carry out needs assessment to

improve performance, achieve goals of the organisa-

tion, determine what potential obstacles need to be

removed, and the e-learning readiness score are cru-

cial to the future of e-learning in our society. Forres-

ter found e-learning to be unpopular with employees

with dropout rates as high as 80%. This is due to

poor quality material mainly comprised of static

HTML pages, which were produced cheaply. This

type of static reading is not effective. On screen

reading retention is 30% lower than reading with

printed materials (

Forrester, 2000). This is not the

enhanced training that e-learning represents.

Furthermore, the survey findings have shown that

the factors that impact organisational e-learning

(management, application, infrastructure, and com-

munication) and their elements should be considered

when making strategic decision about the organisa-

tion e-learning adaptation.

REFERENCES

Forrester, J. P., 2000. ‘The Forrester Report, Online

Training Needs A New Course: Methodology for cost-

benefit analysis of web-based telelearning: Case

Study of the Bell Online Institute’, August.

Galagan, P., 2000. ‘Getting started with e-learning’,

Training and Development 54 (4).

Gotschall, M., 2000. ‘E-learning strategies for executive

education and corporate training’. Fortune, 141 (10)

S5 – S59

Hall, B., 1997. Web-based training cookbook. New York:

Wiley.

Hall, B., and Snider, A., 2000. Glossary: The hottest buzz

words in the industry. http://www.brandonhall.com

(Access date: 18 January 2005).

Hayes, N., 1984. A First Course in Psychology, Third

Edition, Waltham-on-Thames, Thomas Nelson and

Son Ltd.

Huseman, R., and Goodman, J., 1999. Leading With

Knowledge: The Nature of Competition in the 21st

Century, Sage Publications, 2000

Karon, R. L., 2000. ‘Bankers go online: Illinois banking

company learns benefits of e-training’, E-learning, 1

(1) 38-40.

WEBIST 2005 - E-LEARNING

480

Khajanchi, V., and Kanfer A. 2000. Knowledge manage-

ment, National Center for Supercomputer Applica-

tions.

Kotter, J.P., and Hesket, J.L., 1992. Corporate Culture

and Performance, Free Press, 1992, pg. 78.

McGovern, S., 2002. ‘Finding the Right Mix’, edited by

Mark Vernon, Financial Times, Spring.

Nahavandi A., & Malekzadeh, A. R., 1993. Organiza-

tional culture in the management of mergers, Quorum

Books.

Rosenberg M J, 2001. E-Learning – strategies for deliver-

ing knowledge in the digital age, McGraw-Hill, 2001

Urdan, T. A., and Weggen C. C., 2000. Corporate e-

learning: Exploring a new frontier, WR Hambrecht

Co.

Webster, J., & Hackley, P., 1997. ‘Teaching effectiveness

in the technology-mediated distance learning’, Acad-

emy of Management 40 (6).

Whalen, T., and Wright, D., 1999. ‘Methodology for cost-

benefit analysis of web-based tele learning: Case

Study of the Bell Online Institute’, The American

Journal of Distance Education, Volume 13, No1.

Zahm, S., 2000. ‘No question about it – e-learning is here

to stay: A quick history of the e-learning evolution’,

E-learning, 1 (1) 44–47

IMPACTS OF E-LEARNING ON ORGANISATIONAL STRATEGY

481