Fostering Marine Science and Environmental Literacy Through

Marine Education Activities in Science Museum

Yu-Hung Wang

1a

, Yi-Chen Chen

1

, Jia-Ru Liou

1

and Tzu-Hsiang Ger

2

1

Division of Technology Education, National Science and Technology Museum, Kaohsiung, Taiwan

2

Division of Secretariat, National Science and Technology Museum, Kaohsiung, Taiwan

Keywords: Marine Education Activities, Science Museum, Ocean Literacy.

Abstract: The purpose of this study was to understand changes in marine science and the environmental literacy of

Taiwanese people through the use of questionnaires after their participation in marine education activities

held by science museums, so as to further explore the effect of these activities. The results of this study showed

that in terms of marine knowledge, although the correct answer rate of the knowledge items increased clearly

after participation in marine education activities, this increase did not reach a level of significance. This

indicates that the respondents already had a considerable understanding of basic marine knowledge, such as

the development and application of marine resources and how to prevent marine pollution. The marine attitude

variables and behavioral intention variables showed a significant increase after participating in marine

education activities, indicating the marine education activities conducted in science museums are quite

effective and could indeed improve individuals’ marine science and environmental literacy.

1 INTRODUCTION

Ocean Literacy is a growing global education

movement that aims to deepen the relationship

between people and the ocean and to give people a

better understanding of the ocean (Szczytko,

Stevenson, Peterson, Nietfeld, & Strnad, 2019).

Ocean literacy is defined as “an understanding of the

ocean's influence on us and our influence on the

ocean” (Cava, Schoedinger, Strang, & Tuddenham,

2005). An ocean-literate person should understand

the fundamental concepts about the functioning of the

ocean; can communicate about the ocean in a

meaningful way; and is able to make informed and

responsible decisions regarding the ocean and its

resources. Ocean literacy not only increases public

awareness of the ocean, but serves as a way to

encourage more responsible and informed behaviour

by all citizens and stakeholders about the ocean and

its resources (

UNESCO, 2005; NOAA, 2013; Santoro,

Santin, Scowcroft, Fauville, & Tuddenham, 2017)

.

The use of education to understand the marine

environment and protect the ocean is the simplest way

to increase ocean literacy (Szczytko et al., 2019).

Students should learn to understand the ocean from

the earliest years of elementary school. Schools

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8515-7303

should promote the inclusion of ocean-related topics

in the school curriculum and train teachers to get

professional knowledge of the ocean. In addition,

cooperation with local aquariums, science centers,

museums, and other informal educational institutions

should be strengthened to promote ocean-themed

activities (

Mokos, Realdon, & Zubak Cˇižmek, 2020)

.

Taiwan is surrounded by the sea. Due to its

geographical location, marine education has been

actively promoted and popularized since 2000 in

Taiwan. In schools, the development of marine

education courses is actively encouraged, and

teachers are trained to integrate marine issues into

their teaching. In the new curriculum (junior and

senior high school), five learning topics (marine

leisure, marine society, marine culture, marine

science and technology, and marine resources and

sustainability) have been listed to encourage students

to understand the ocean, get closer to the ocean, and

learn how to protect the ocean (Wen & Lu, 2013).

However, the knowledge background of most

teachers is unrelated to the ocean, and they rarely

have access to marine education courses in the

process of teacher development and education.

Therefore, in order to promote marine education, it is

important to seek resources from non-formal

Wang, Y., Chen, Y., Liou, J. and Ger, T.

Fostering Marine Science and Environmental Literacy Through Marine Education Activities in Science Museum.

DOI: 10.5220/0011888300003536

In Proceedings of the 3rd International Symposium on Water, Ecology and Environment (ISWEE 2022), pages 29-34

ISBN: 978-989-758-639-2; ISSN: 2975-9439

Copyright

c

2023 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. Under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

29

educational institutions. In Taiwan, schools of all

levels often cooperate with two ocean-themed

museums, namely, the National Museum of Marine

Science and Technology (NMMST) and the National

Museum of Marine Biology and Aquarium

(NMMBA), to provide professional marine education

equipment for peer-coaching and learning (Lee, Liu,

& Yeh, 2019). The cooperation of schools with one

another as well as the use of informal resources are

the most effective means to implement high-quality

marine education (Lee, Liu, & Huang, 2015; Chang

& Lwo, 2016).

The purpose of this study was to develop a

questionnaire to investigate the marine science and

environmental literacy of Taiwanese people. The

questionnaire was used to explore the changes in

various variables, such as marine knowledge, marine

attitudes, and behavioral intentions, before and after

participating in the marine education activities and to

further explore the effects of these activities.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Marine Education Activities

The purpose of marine education activities is to build

ocean literacy by transmitting and accumulating

knowledge, thereby fostering ocean protection

attitudes and behaviors. There are 10 large teaching

aids in marine education activities, and the themes

cover two parts. One part focuses on ocean energy

and resources, including teaching aids of Wave

Power Generation, Water Flow Power Generation,

and Understanding Deep Ocean Water. These

resources can increase people’s understanding of

marine renewable energy and resource development

through interesting hands-on experiences. The other

part focuses on the marine environment, including

teaching aids related to Understanding Marine Waste,

Ocean Defense Battle, and Taking Action to Protect

the ocean, which can help people understand the

seriousness of marine pollution and learn how to

protect the ocean and make the ocean sustainable

through learning methods such as interactive games

and questions and answers.

According to the above literature discussion and

the general public’s awareness of the ocean in

Taiwan, this study addressed marine science and

environmental literacy, defined as including marine

knowledge, marine attitudes, and marine behavioral

intentions. The relevant definitions are shown in

Table 1.

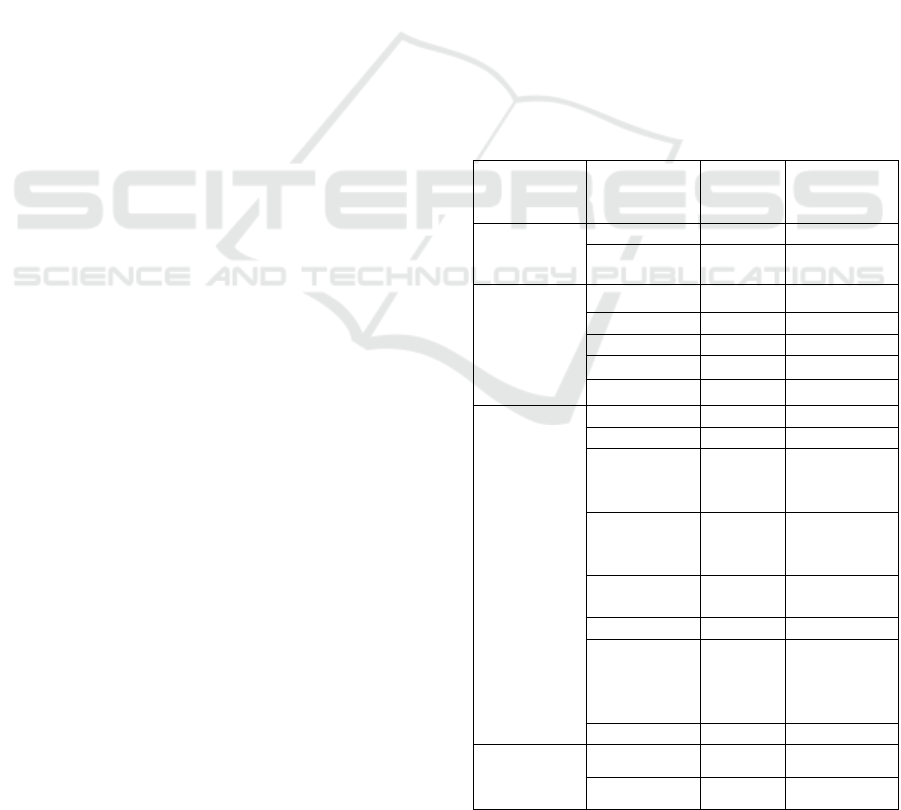

Table 1: Definitions of marine science and environmental

literacy.

Domain Subscale Definition

Knowledge

Marine science

and technology

Understand the

structure of the

ocean and the

environment in

which it is formed,

including the

cognition of ocean

currents, sea waves,

sea breezes, and

other marine

science

connotations.

Marine

environment

and resources

Understand the

relationship

between marine

resources and life,

as well as the

impact of human

activities on marine

ecolo

gy

.

Attitude

Concerns for

marine

resources

Develop a proper

attitude and interest

in the development

of marine resources.

A friendly

attitude towards

the marine

environment

Gain the potential to

think about the

impact of the

marine environment

on human life.

Behavior

Intention

Initiative and

active

p

artici

p

ation

Actively engage in

and explore ocean-

related issues.

Take actions to

protect the

ocean

Take active actions

and be active in

influencing others

to

p

rotect the ocean.

2.2 Questionnaire Design

A structured questionnaire was used to measure the

effectiveness of marine education activities, and pre-

and post-tests were used to assess public learning

outcomes. The questionnaire consists of three parts.

Part 1 involves personal information, including

gender, age, source of marine knowledge, frequency

of seaside recreation. Part 2 covers marine knowledge

questions presented as multiple-choice answers. Part

3 surveyed the marine attitudes and marine

behavioural intentions items, scoring responses using

a 5-point Likert scale.

Item discrimination, factor analysis and reliability

analysis were used to test the research scale. When a

marine education event was held at the National

Science and Technology Museum (NSTM), a

ISWEE 2022 - International Symposium on Water, Ecology and Environment

30

questionnaire survey was conducted and 150 people

who had participated in the event were selected. The

sample size meets the requirements of pre-test

analysis. The difficulty of Part 2 questions is between

0.66 and 0.79, and the correlation is significant,

indicating that the difficulty of the questions is

moderate and the discrimination is high. The third

part deals with the marine attitudes and marine

behavioral intentions project. The marine attitude

items were divided into two sub-scales: concern for

marine resources (six items) and a friendly attitude

towards the marine environment (six items). The

marine behavioral intention items were divided into

two sub-scales: initiative and active participation

(five items) and taking action to protect the ocean

(nine items). In terms of factor and reliability

analysis, five items related to attitude and two items

related to behavioral intention were deleted. After

deletion, the factor loadings were in the range of 0.76-

0.93, and the Cronbach's alpha coefficient value for

each variable was in the range of 0.92-0.94, which

met the criterion of reliability above 0.70 proposed by

Nunnally and Bernstein (1994). Therefore, the

reliability of the scale is high and acceptable.

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1 Analysis of the Basic Information

The subjects of this study were Taiwanese citizens

who participated in marine education activities held

at NSTM. Before participating in the event, the public

filled out a pre-test questionnaire. After filling out the

questionnaire, they began to participate in marine

education activities. Through the explanation of the

instructor and hands-on operations, the respondents

learned knowledge related to the ocean, with the

expectation of enhancing their awareness of attaching

importance to the ocean. After the activity, the

respondents filled out the post-test questionnaire to

measure the changes in their knowledge, attitudes,

and behaviors after participating in the activities. A

total of 360 questionnaires were distributed in this

study, and 328 were returned. After deleting the

invalid samples, 316 valid samples remained, and the

effective recovery rate was 96.3%.

This study took adults with the age over 18 as the

research subjects. Among the 316 questionnaires, in

terms of the demographic data of the respondents,

female was the most common gender (189 females,

accounting for 59.81%); in terms of age, people aged

40 – 49 (125 people) and those aged 30–39 (122

people) were the most, accounting for 39.56% and

38.61% of the total, respectively. The question for the

learning sources of ocean knowledge adopted the

method of multiple choice. Among the respondents,

212 people (67.09%) believed that they usually

learned relevant knowledge from museums, followed

by 189 people (59.81%) who believed that they

learned relevant knowledge from television media.

This result indicated that museums and television

media, which both can be seen as non-formal

educational institutions, play an important role in

promoting marine education. In addition, 237 people

(75%) had participated in seaside activities one to five

times in the past year, while only 49 people (15.51%)

had not participated in any seaside activities in the last

year. In terms of seaside activities, the most popular

activity was coastal relaxation and recreation (209

people, accounting for 66.14%), followed by

sightseeing at fishing ports or harbors (180 people,

accounting for 56.96%). This result indicated that

Taiwanese people often go to the seaside, and they are

willing to get close to the ocean and engage in related

leisure activities. The analysis of the related

respondents is shown in Table 2.

Table 2: Basic data analysis table of the respondents.

Item Category

Sample

size

(N)

Percentage

(%)

Gender

Male 127 40.19%

Female 189 59.81%

Age

18~29 37 11.71%

30~39 122 38.61%

40~49 125 39.56%

50~59 10 3.14%

Above 60 22 6.96%

Source of

knowledge

(Multiple

choice

question)

School 141 44.62%

TV media 189 59.81%

Newspaper

and

magazine

100 31.65%

Film (film

related to

the ocean)

123 38.92%

Social

media

(

FB

)

110 34.81%

Museum 212 67.09%

Instruction

from the

elder

(p

arents

)

23 7.28%

Others 20 6.33%

Number of

trips to the

seaside in

Never 49 15.51%

1-5 times 237 75.00%

Fostering Marine Science and Environmental Literacy Through Marine Education Activities in Science Museum

31

the past year

6-10 times 16 5.06%

More than

10 times

14 4.43%

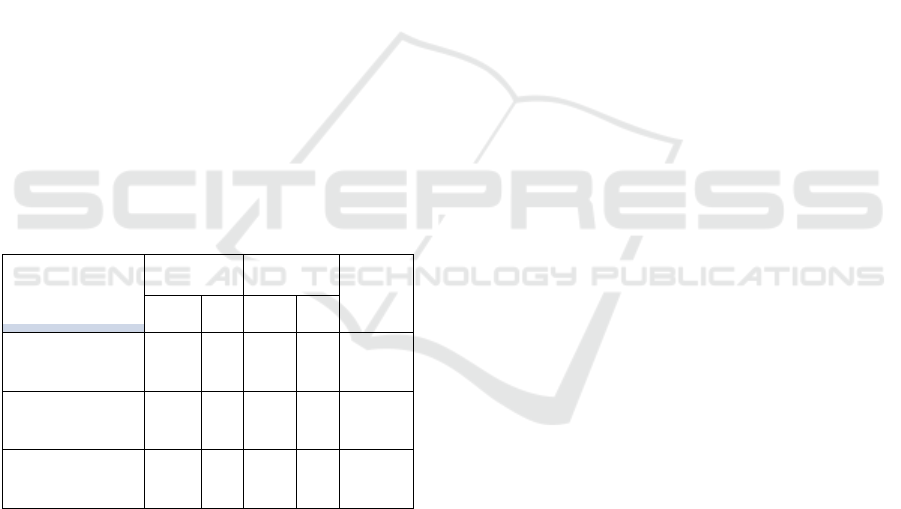

Activities at

the seaside

(Multiple

choice

question)

Cleaning the

b

each

72 22.78%

Intertidal

observation

and

experience

123 38.92%

Sightseeing

in fishing

ports or

harbors

180 56.96%

Coastal

relaxation

and

recreation

209 66.14%

Swimming

56 17.72%

Snorkeling

44 13.92%

Canoein

g

7 2.22%

Others 26 8.23%

3.2 Analysis of the Marine Knowledge

Variable

There were two factors in the variables of marine

knowledge. According to the statistical results shown

in Table 3, the average score of the respondents in the

pre-test of the overall factors of marine knowledge

was 6.20 (a correct answer rate of 77.22%). After

participating in marine education activities, the

average score of the post-test was 6.29 (a correct

answer rate of 78.48%), and the t-test value of the

paired sample was 1.30 (p=.194). In terms of the

overall factor or sub-factors, although the average

score of the post-test was slightly improved, it did not

reach a significant level. This shows that the

respondents already had relevant marine knowledge

before participating in marine education activities.

For example, they had a good understanding of

various energy developments, such as offshore wind

power generation on the ocean and how to protect the

ocean. After participating in marine education

activities, there was no significant growth in their

knowledge of the ocean. The detailed analysis results

are shown in Table 3.

Table 3: Paired samples t-test results of the marine

knowledge scores (N = 316).

Factors

Pre-test Post-test

t-test

(p)

M

SD

M

SD

Marine science

and technology

3.72 1.21 3.76 1.16

.76

(.45)

Marine

environment

and resources

2.48 .73 2.53 .71

1.25

(.21)

Total scale

6.20 1.60 6.29 1.54

1.30

(

.19

)

3.3 Analysis of the Marine Attitude

Variable

The pre-test average of the total scale for the ocean

attitude variable was 4.54; after participating in the

marine education activities held by the science

museum, the post-test average was 4.59. The t-test

analysis of the results indicated a significant

difference (p=.01). In terms of the sub-factors, after

participation in marine education activities, concern

for marine resources and friendly attitude towards the

marine environment both showed significant growth

(p=.04 and p=.01). This result indicated that the

respondents had a more positive and active attitude

towards concern for marine resources and the marine

environment after these activities. For example, they

felt that it was interesting to discuss marine science

issues, and they believed that maintaining the

sustainability of the marine environment was a

meaningful challenge. The detailed pre-test and post-

test results for ocean attitude are shown in Table 4.

Table 4: Marine attitudes using the paired-samples t-test (N

= 316).

Factors

Pre-test Post-test

t-test

(p)

M

SD

M

SD

Concerns for

marine resources

4.47 .58 4.52 .55

2.03

(.04)

A friendly attitude

to the marine

environment

4.62 .52 4.68 .47

2.64

(.01)

Total scale

4.54 .51 4.59 .48

2.58

(

.01

)

ISWEE 2022 - International Symposium on Water, Ecology and Environment

32

3.4 Analysis of the Marine Behavioral

Intention Variable

The pre-test average of the total scale for the marine

behavioral intention variable was 4.50; after

participating in the marine education activities held

by the science museums, the post-test average was

4.56. The t-test analysis of the results indicated a

significant difference (p<.01). In terms of the

comparative analysis of each sub-factor, initiative and

active participation showed significant growth after

the respondents’ participation in the marine education

activities (p<.01), indicating that the respondents

intended to actively pay attention to news or events

related to marine issues after these activities.

However, there was no significant difference in

taking action to protect the ocean, such as not

throwing garbage into the ocean or not destroying the

marine ecology, after participating in marine

education activities (p=.29). This study speculated

that the respondents already had the behavior

intention to protect the ocean before participating in

the marine education activities, therefore this factor

would not change after their participation. The

detailed pre-test and post-test analysis results for

marine behavioral intentions are shown in Table 5.

Table 5: Marine behavioral intentions using the paired-

sample t-test (N = 316).

Factors

Pre-test Post-test

t-test

(p)

M

SD

M

SD

Initiative and active

p

articipation

4.27 .67 4.39 .60

3.87

(<.01)

Take actions to

p

rotect the ocean

4.65 .49 4.68 .47

1.05

(

.29

)

Total scale

4.50 .50 4.56 .46

2.89

(

<.01

)

4 CONCLUSIONS

The main objective of this study is to develop a survey

scale of Taiwanese marine science and environmental

literacy. In addition, a questionnaire survey was

conducted through the marine education activity of

the science museum to explore the relationship

between various variables among the scales, and to

further explore the effect of the activity. In terms of

questionnaire preparation, according to the

preliminary test results of item discrimination,

exploratory factor analysis and reliability analysis,

after deleting inappropriate items, the scale has good

reliability and validity.

Taiwan is surrounded by water, and the general

public has many opportunities to access the ocean. In

addition, through publicity in schools and the media,

the public has acquired a basic concept of protecting

the ocean. This study found that the respondents

already had a considerable degree of marine science

and environmental literacy before participating in

marine education activities. However, after

participating in these activities, the attitude and

behavioral intention of the respondents towards the

ocean could still be effectively improved. In terms of

marine knowledge, the respondents had a correct

answer rate of about 77% for questions related to

marine science and environmental knowledge before

participating in the marine education activities, and

this grew to 78% after the activities. Although their

understanding of relevant knowledge was improved,

it did not reach a significant level, indicating that the

public in Taiwan already has a considerable

understanding of basic marine knowledge, such as the

development and application of marine science and

technology, as well as the prevention of marine

pollution.

In terms of marine attitudes, the comparison of the

results showed that the respondents’ concern for the

ocean had a significant increase after participating in

marine education activities. These activities are held

in science museums, and they contain many

interactive teaching aids related to marine science.

Therefore, such activities could promote people’s

interest in marine science research. For example, the

respondents showed great interest in understanding

wave power generation, observing ocean tide

changes, and even discussing the topography of

Taiwan's coastline and its causes. In addition,

participation in related activities has a considerable

impact on people's attitudes towards the marine

environment. The results indicated that after

participation in such activities, people believe they

can help reduce harm to the ocean by preparing their

own reusable bags or reducing the amount of waste

they produce.

Marine behavioral intentions contained two

factors, namely, initiative and active participation,

and taking action to protect the ocean. Among these

two factors, initiative and active participation showed

significant growth after participating in marine

education activities. The questionnaire results

indicated that the public will take the initiative to pay

attention to marine education activities and will

actively participate in them after these activities.

Fostering Marine Science and Environmental Literacy Through Marine Education Activities in Science Museum

33

Therefore, participation in activities held by science

museums could help people understand the

importance of the ocean and increase their interest in

participating in related activities. In general, in terms

of taking action to protect the ocean, people in

Taiwan already have a sense of protecting the ocean,

and this is shown through not carelessly throwing

away garbage and by showing respect for marine life.

People in Taiwan do these things to protect the ocean,

and such actions show a close connection with these

marine education activities.

In terms of the survey and analysis of the basic

data, the respondents had experienced being close to

the ocean and enjoyed going to the seaside for leisure

and recreational activities, indicating that people in

Taiwan attach increased importance to the sustainable

development of the ocean. In addition, in terms of the

source of marine knowledge, most of the respondents

believed they could get marine knowledge from

museums, and sometimes, museums play an even

more important role than schools. Taiwan currently

has two ocean-themed museums, and they spare no

effort to promote marine education. Moreover, the

research focus of this study was the science museum

in southern Taiwan. In response to ocean

conservation policies, the museum conducts

promotional activities for marine education and

encourages the public to participate in these

experiences, further demonstrating its influence in

promoting marine education. The findings of this

study also proved that people could indeed improve

their marine science and environmental literacy by

participating in promotional activities for marine

education.

REFERENCES

Cava, F., Schoedinger, S., Strang, C., & Tuddenham, P.

(2005). Science Content and Standards for Ocean

Literacy: A Report on Ocean Literacy. Retrieved

October 10, 2021, from

http://www.cosee.net/files/coseeca/OLit04-

05FinalReport.pdf

Chang, C. C., & Lwo, L. S. (2016). A research on the

importance of the learning contents of marine

education. Curriculum and Instruction Quarterly,

19(2): 53-82.

Lee, H. S., Liu, S. Y., & Huang, S. H. (2015). In-service

teachers’ perspectives and pedagogies for marine

education in Taiwan. In 31st Annual International

Conference of Association of Science Education

Taiwan (pp. 212-213), Pingtung, Taiwan.

Lee, H. S., Liu, S. Y., & Yeh, T. K. (2019). Marine

Education Through Cooperation: A Case Study of

Opportunity in a Remote School in Taiwan. In:

Fauville, G., Payne, D., Marrero, M., Lantz-Andersson,

A., Crouch, F. (eds), Exemplary Practices in Marine

Science Education (pp. 191-205). Springer, Cham.

Mokos, M., Realdon, G., & Zubak Cˇižmek I. (2020). How

to Increase Ocean Literacy for Future Ocean

Sustainability? The Influence of Non-Formal Marine

Science Education, Sustainability, 12(4): 10647.

NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric

Administration). (2013). Ocean Literacy: The essential

principles and fundamental concepts of ocean sciences

for learners of all ages. Retrieved September 20, 2022,

from

https://www.coexploration.org/oceanliteracy/documen

ts/OceanLitChart.pdf.

Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. H. (1994). Psychometric

theory (3rd ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Santoro, F., Santin, S., Scowcroft, G., Fauville, G., &

Tuddenham, P. (2017). Ocean Literacy for all: A

Toolkit. Paris: UNESCO Venice Office.

Szczytko, R., Stevenson, K., Peterson, M. N., Nietfeld, J.,

& Strnad, R. L. (2019). Development and validation of

the environmental literacy instrument for adolescents.

Environmental Education Research, 25(2): 193–210.

UNESCO (United Nations of Education Scientific and

Cultural Organization). (2005). Aspects of Literacy

Assessment: Topics and Issues from the UNESCO

Expert Meeting. Paris: UNESCO.

Wen, W. -C., & Lu, S. -Y. (2013). Marine environmental

protection knowledge, attitudes, behaviors, and

curricular involvement of Taiwanese primary school

students in senior grades. Environmental Education

Research, 19(5): 600-619.

ISWEE 2022 - International Symposium on Water, Ecology and Environment

34