Teachers’ Viewpoint on Online Courses

Päivi Kinnunen

1

and Taina Eriksson

2

1

School of Business, Aalto University, Finland

2

Turku School of Economics, Finland

Keywords: Pedagogical Support, Teaching Online for the First Time, Business Studies.

Abstract: Many universities that have previously focused on offering blended learning or face to face courses are

currently starting to offer more and more also online courses. This paper takes a closer look at the background

and perceptions of eight teachers who are about to teach an online course for the first time. More specifically,

we take a look at the teachers’ perceptions of themselves as adopters of new pedagogy and new technology

as well as their perceptions of strengths and weaknesses of online courses. The preliminary results suggest

that our teachers feel rather comfortable with the new technology and especially with the new teaching

methods. Most of the teachers identified themselves as innovators or early adopters of new teaching methods.

Teachers perceived flexibility and efficiency as the most prevailing strengths of online teaching. On the other

hand, weaknesses included workload, technical challenges, and various topics that relate to the lack of face

to face interaction. We conclude by discussing what kind of pedagogical support and training the online

teachers would benefit from.

1 INTRODUCTION

Business studies provide skills and knowledge that

are useful in many fields. For instance, management,

entrepreneurship, and marketing are skills that many

need once they enter the work life regardless of their

first field of study. Thus, the demand for business

studies among non-business university students is

significant. To better cater for this identified need of

business studies, the board of Association of Business

Schools Finland decided that business schools should

develop jointly an entire program of online courses.

The program would be targeted to non-business

students from the different faculties from all

universities with business school or faculty of

business in Finland (ABS 2017). This program of

online courses is in line with the strategic initiatives

of Finnish Ministry of Education and thus is

supported financially by the Ministry. The

universities that produce the courses get some money

to cover, for instance salaries of teachers and teaching

assistants, materials, and licence costs. The program

of online courses is free of charge for the university

students.

In fall 2017, a new a pilot version of totally online

study module on Business studies was launched as a

collective effort of ten Finnish universities. The study

module consists of eight five credit courses (5 ECTS

equals 135 hours of student work): Management and

organization; Corporate social responsibility;

Accounting; Entrepreneurship; Marketing and sales,

Economics, Business law, and Business simulation.

Each course is taught either by one university or in a

collaboration of two to three universities. The courses

are planned to accommodate up to 1000 students.

However, on the pilot year, the number of students at

each course is limited to 250 students.

The study module is offered for all non-business

major students at most Finnish universities from fall

2017 onwards. The module is planned to provide

students a lot of flexibility. Students can take which

ever, and as many courses they want and find useful

for themselves. However, if students want to include

their studies into their degree as a business minor,

they have to take at least five courses (four of which

they can choose freely and a Business simulation

course that bridges together the other four courses).

On the pilot academic year 2017-2018, there are

altogether 18 teachers from nine universities that

produce the eight courses. In this ongoing study, we

investigate the teachers’ perceptions of online

teaching and learning. The overall goal of our

research project is to get an insight into the online

teachers’ pedagogical thinking and what kind of

412

Kinnunen, P. and Eriksson, T.

Teachers’ Viewpoint on Online Courses.

DOI: 10.5220/0006786904120417

In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2018), pages 412-417

ISBN: 978-989-758-291-2

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

pedagogical and/or technical support universities

should provide to support our teachers in their work.

However, in this paper we are going to delimit our

focus on getting to know our teachers better and what

their perceptions are on the strengths and weaknesses

of online courses. Our research questions are:

RQ1: To what degree the teachers who take on the

task of creating and teaching an online course, are

forerunners in adopting new teaching methods and

technology?

RQ2: How do the teachers who are about to teach

online business courses perceive the strengths and

challenges of online courses?

2 ONLINE COURSES – PROS

AND CONS

The pros and cons of online courses have been

discussed by many. The identified advantages and

disadvantages relate to all actors of the instructional

process; students, teachers, and the university.

Fedynich (2013) summarizes the strengths as:

freedom of when and where to study, different

options of participating the course from asynchronous

to synchronous, possibility for various teaching

methods, and cost efficient for the university. Cook

(2007) agrees with the many of the above listed

strengths and adds to the list individualised learning

possibilities (e.g., choosing the study pace) and the

use of such teaching methods that would be difficult

or inconvenient in traditional settings (e.g. virtual

simulations). Finally, Cook (2007) and Baleni (2015)

also adds possibility of providing immediate

customized feedback and a venue for formative

assessment. Online learning platform may also serve

administrative purposes as it keeps automatically

record on, for instance, which assignments students

have submitted.

As a summary, the advantages of online courses

relate to all actors in an online course. Students, for

instance, benefit from flexible and accessible courses,

teachers have more possibilities to use new teaching

methods, and the university is thought to save money.

The identified weaknesses of online teaching, on

the other had include (Fedynich 2013; Cook 2007):

online courses require computer literacy from the

students and online access, poor instructional design,

lack of face to face time which may lead to social

isolation, teaching and feedback may not be as

individualised as one would hope for, and finally that

technology is used for the sake of technology.

As a summary, both students and teachers face

some challenges. Students may have to, for instance,

cope with feelings of isolation. Teachers have to

make a transition from the way they teach traditional

course to new way of how to design online course.

3 ADOPTING INNOVATIONS

We use Roger’s innovation adoption curve (diffusion

of innovations theory) as a framework to get an

overall understanding of how eager the teachers who

we study in this research project are to adopt new

innovations. According to Roger’s theory (Rogers

2003; Hixon et al. 2011), adopters of new innovations

can be divided into five categories: innovators, early

adopters, early majority, late majority, and laggards.

The distribution of people in these categories is

described to be close to the Bell’s curve. Only a very

small proportion of adopters (2,5%) are typically

innovators, who are willing to be the first ones to try

even if there is a risk of failing. Early adopters

(13,5%) are among the first ones to try new, selected

innovations. Early majority adopters’ (34%) wait

until early adopters and innovators have gained some

experiences of the innovation. Late majority (34%)

adopts the innovations later than most of their peers,

perhaps because of the peer pressure or emphasized,

new code of conduct in the community. Finally,

laggards (16%) are traditional and may adopt a new

innovation only when they become mainstream.

Roger’s innovation adoption curve has been used

in many research project to understand and analyse

the adoption of learning technology (see, e.g. Hixon

et al. 2011; Soffer 2010). In this study, the Roger’s

framework provides a guideline to understand how

the teachers as a group react to new challenges like

adopting new teaching methods and becoming a

teacher in an online course (which requires somewhat

lot of technical skills in addition to pedagogical

skills).

4 RESEARCH DESIGN

At the beginning of fall 2017, just before the first

online course of the module started, we sent out a

questionnaire to all eighteen teachers who produce

the eight courses. We sent two reminders to increase

the response rate. There were altogether 18 questions

in a questionnaire that related to:

background info (age, teaching experience,

work title)

Teachers’ Viewpoint on Online Courses

413

educational background (highest degree,

pedagogical education)

approach to adopting new pedagogical and

technological innovations (multiple choice

question)

perceptions of pros and cons of online teaching

(open ended)

plans and experiences relating to the course one

is going to teach (open ended)

needs and expectations regarding the

pedagogical support (open ended)

The data relevant for this paper consists of the

answers to four first question types. The results are

represented mainly as descriptive statistics. The

answers for the open- ended questions we mostly

rather concise. The open-ended answers are

categorized and summarized to convey the main

aspect of the responses.

5 RESULTS

After two reminders eight teachers returned the

questionnaire. Respondents represented the teachers

of the 6/8 courses that are taught in a module. Most

teachers had a PhD in Business and two respondents

had Master’s degree in Business. Three respondents

worked as university lectures, four as researcher/post-

doctoral researchers. One respondent worked as a

development director. Respondents’ teaching

experience at the university level varied from 0 to 15

years (mean 6,9 years). There was also great variation

in the amount of pedagogical studies the teachers had

taken. Some had taken no pedagogical courses

whereas one of the teachers had studied 80 ETCS

(mean 26,4 ETCS). However, only one teacher said

that his/her university requires pedagogical studies

from the teachers in case they want to proceed in their

career at the university (e.g., get a promotion on

lecture/tenure track). One stated that no pedagogical

studies are required, and the rest of the respondents

did not know whether pedagogical studies are

required in their institutions.

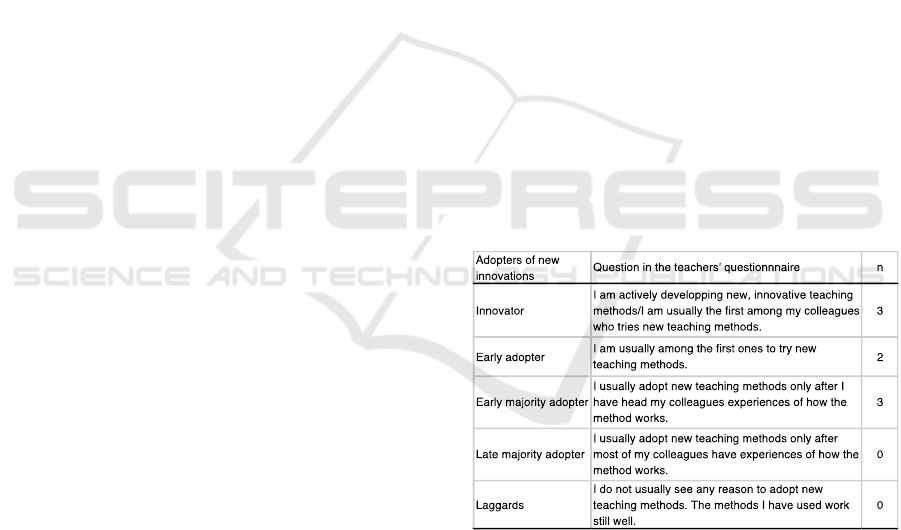

5.1 Forerunners or Not?

We asked the teachers to estimate to what degree they

are the forerunners or conservative when it comes to

adopting new teaching methods. Five out of eight

teacher identified themselves as being the first

(innovator), or among the first teachers (early

adopters) in their community to try new teaching

methods. The remaining three teachers prefer to wait

until they have heard about their colleagues’

experiences of the new teaching method before trying

the method themselves (early majority adopters)

(Table 1). An overall observation is that the teachers

who are teaching the online courses in our study

module are more forerunners than conservative in

adopting new teaching methods.

We also did a cross tabulation to see if we could

see some tentative relations between how

experienced teachers were (years of teaching

experience) and how they positioned themselves into

Roger’s innovation adoption curve. The data suggests

that, in general, work experience in teaching seems to

be in relation with how innovative our teachers are.

All three innovator teachers belonged to the four most

experienced teachers in our data set. The three

innovator teachers had seven to fifteen years of work

experience as a teacher at a higher education level.

The majority of teachers who identified themselves as

early adopters or early majority adopters had teaching

experience up to six years.

We observed the similar trend between teachers’

pedagogical studies and how eager they were to adopt

new teaching methods. In general, the teachers who

had studied pedagogical studies were also more often

innovators or early adopters than teachers who had

not studied pedagogical studies.

Table 1: Adopting new teaching methods.

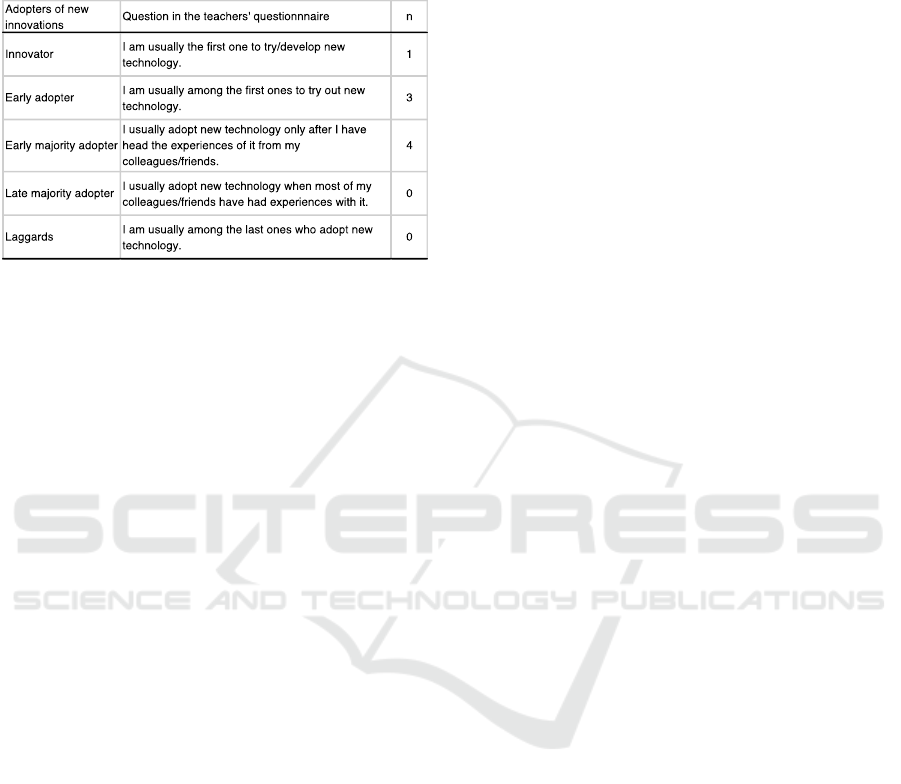

In a similar manner, we asked the teachers to think

to what degree they are among the first adopters of

new technology. Only one teacher identified

him/herself as being the innovator/the first adopter of

new technology among peers. Three teachers

identified themselves as early adopters, and four

teachers said they usually adopt new technology only

after they have heard reviews from others (Table 2).

Even though the profile of the answers is slightly

more conservative in general compared to the

adoption of new teaching methods, our respondents

CSEDU 2018 - 10th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

414

could still be described as either early adopters or

early majority adopters rather than late adopters.

Table 2: Adopting new technology.

We again did a cross tabulation to see if there were

some tentative relations between the teaching

experience and pedagogical studies and how teachers

positioned themselves as adopters of technology.

However, the answers were scattered and we could

not observe any coherent trend in the data.

Since our data pool in this pilot study is small we

could not make any statistical tests to the data.

Therefore, we treat observations as preliminary

results that provide hypothesis for the later stages of

our study.

5.2 Strengths and Weaknesses of

Online Courses

Respondents elaborated on their perceptions of the

pros and cons of online teaching and learning in two

open ended questions. Teachers were asked to write

about the strengths and weaknesses from the

viewpoint of students, teachers, and the university. In

this study we are not interested directly in pros and

cons of online courses. Instead, we are interested in

teachers’ perceptions of pros and cons of teaching

and learning in an online course.

5.2.1 Teachers’ Perceptions of Strengths of

Online Courses

Based on the teachers’ reflections, the most

prevailing strength of online courses from all three

viewpoints (students, teachers’, university) was

flexibility. The possibility to study without time or

location related limitations was seen to cater

especially well adult learners, part time students, and

students who study the topic as their minor. In

addition, flexibility was also understood as an

opportunity review the learning material several

times if needed. For instance, a student can watch a

teaching video as many times as he wants. Finally, the

online courses offer an opportunity for faster study

pace for those students who are willing to do so.

Faster study phase transfers to shorter study times in

general, which in turn are perceived as [financially]

beneficial for the universities.

Another strength of online courses that was

prevailing in the data was efficiency. Online courses

were seen an efficient especially from the viewpoints

of teachers and university. From the teachers’

viewpoint efficiency related to the possibility of

reusing the teaching material. One the hand, looking

efficiency from the viewpoint of the university,

online courses were perceived as a cost-efficient way

of teaching. For instance, online courses do not

require physical classrooms.

Both flexibility and efficiency were mentioned in

the data by several respondents. Other strengths that

were mentioned only by one or two respondents

included aspects such as conveying modern image of

the university and attracting new students to the

university.

We also looked at whether respondents’ status as

an innovator, early adopter, or early majority adopter

had any effect on how many strengths teachers

mentioned. However, the data suggest that there were

no big differences between the teachers. In average,

teachers mentioned three to four strengths regarding

online courses.

5.2.2 Teachers’ Perceptions of Weaknesses of

Online Courses

The most often mentioned weakness of online courses

from the students’ viewpoint related to the workload.

The teachers thought that some students might have a

false image that online courses are easier because

there is no face to face teaching sessions. Thus, some

students might not reserve enough time for studying.

In addition, online courses require good study skills

from students, such as an ability to study

independently and time management skills.

The workload was also seen as a challenge for the

teachers. The amount of preparation that is needed

before the online course starts is great. Transforming

existing teaching material from a face to face course

to online material takes a lot of time. On the other

hand, teachers perceived that there is a misconception

at the university level that online courses do not need

additional resources. This is in a clear contradiction

with the view that creating and teaching an online

course take a lot of teachers’ time.

The possible technical problems were also

mentioned often in the data. Both students and

Teachers’ Viewpoint on Online Courses

415

teachers have to deal with technical challenges

relating to the learning management system and other

technology that is used in the course.

The root cause of the third perceived weakness of

online courses is the lack of face to face interaction in

online courses. This poses several challenges both to

students and teachers. If the online course does not

encourage interaction between students, some

students might feel lonely and they do not have the

benefit of peer support. On the other hand, if online

courses require group work, online groups might be

difficult to manage.

For the teachers, totally online course poses also

several challenges. First, teachers find it difficult to

convey their own enthusiasm towards the topic of the

course in an online course. Second, some teachers

anticipated that it might be more difficult to identify

students who have difficulties understanding the

topic. Third, teachers find it more challenging to find

ways to assess to what degree the intended learning

outcomes are achieved in the online course. Finally,

since all the assignments and possible exams are done

online, teachers find that they cannot be 100% sure

who has actually done the assignments.

The perceived challenges of online teaching relate

also to teachers’ and universities’ set ways of thinking

and organizing teaching. For some teachers,

transferring own teaching from face to face teaching

model to an online teaching, is a big change. It

challenges teachers’ old ways of thinking and

organizing courses. In addition, online courses pose a

similar kind of challenge to the university as an

organization. The existing way how teaching related

[administrative] processes are organized is not

catering the needs of the online minor that is

organized as a joint effort of several universities.

Teachers who identified themselves as innovative

when it comes to adopting or creating new teaching

methods suggested in average 5,7 weaknesses of

online teaching. In contrary, teachers who were early

adopters or early majority adopters identified in

average 3,3 weaknesses. Innovators thus seem to be

slightly more aware of/have thought of more about

the challenges the online teaching poses to students,

teachers and the university.

6 DISCUSSION AND

CONCLUSIONS

Taking on the responsibility of planning and teaching

an online course as a part of a larger, national online

business minor initiative requires courage, technical

skills and online pedagogical skills from the teachers.

We conducted this pilot study to learn from this

process and be better informed about what kind of

support our online teachers might need in the future.

We posed two research questions for this first

ongoing research project: 1) To what degree the

teachers who take on the task of creating and teaching

an online course, are forerunners in adopting new

teaching methods and technology? And 2) How do

the teachers who are about to teach online business

courses perceive the strengths and weaknesses of

online courses?

The size of the data pool in this pilot study is small

and thus the results and the conclusions in this paper

should be treated as tentative. However, for sake of

the following phases of the bigger research project, it

was essential that we were able to get at least some

data before the teachers actually teach the courses.

This data gives us some ideas for what kind of

pedagogical and technical support and training novice

online teachers might benefit from.

Based on the preliminary analysis, the majority of

the eight teachers who answered the questionnaire

were either innovators, early adopters or early

majority adopters of new teaching methods. On the

contrary, the teachers were slightly more conservative

when it came to adopting new technology in general.

However, none of the teachers belonged to late

majority or laggards group. Based on the small data

set, the teaching experience and pedagogical studies

seem to be in relation to teachers’ eagerness to adopt

new teaching methods. In general, the more teaching

experience and pedagogical studies the teachers had

more often they were innovators or early adopters of

new teaching methods. Experience and pedagogical

studies have perhaps given teachers the confidence to

try new teaching methods.

Teachers identified several strengths and

weaknesses in online courses. Many of these

corroborate the pros and cons identified by others too

(Cook 2007; Fedynich 2013). For instance, different

embodiments of flexibility of teaching and studying

in online courses is often mentioned in the literature

and it was also the most often mentioned strength of

online courses in our data. Teachers identified also

weaknesses, such as a possibility for social isolation

and technical issues that are mentioned in the

literature.

However, some of the challenges that were not

mentioned in the literature but came up in our data

were: 1) There is a need for a change in teacher’s own

way of thinking about teaching and learning.

Teaching online challenges old perceptions that are

based on face to face teaching. 2) The rigidness of

CSEDU 2018 - 10th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

416

universities’ organization and the way administration

is organized. However, this latter challenge is related

perhaps more to the fact that several universities

provide the courses rather than the actual online

courses.

6.1 Support for the Novice Online

Teachers

The results provide some ideas for what kind of

pedagogical and technical support teachers would

benefit from. Pedagogical support and training are

needed to scaffold the change in how teachers think

about teaching and learning. The existing thoughts

are based on classroom teaching and learning and

now the online courses challenge the thoughts.

Changing one’s way of thinking is a process where

both pedagogical training, peer support and first-hand

experience of online teaching are essential.

On a practical level, the teachers would likely

benefit from training modules on topics, such as:

How instructional designs can help

students to manage their time and learn

efficient study skills.

Different pedagogical and technical ways

how to detect struggling students early in

an online course.

The role of assessment and different kinds

of assessment possibilities.

The ways to convey teachers’ presence and

own enthusiasm towards the topic of the

course.

How to create a sense of community and

facilitate group work in an online course.

Since learning technology often offers some

solutions for above mentioned challenges, we suggest

that the training modules combine the pedagogical

and technological training in one. When the

pedagogical challenge is identified and pedagogically

sound solutions have been designed, teachers should

get the technical tools and skills to realize the solution

in practices.

The need for both pedagogical and technical

support and training units is also recognised among

experienced online teachers even though the

emphasis and content of the support might change as

teachers get more experience in online teaching (Orr

2009). This is something that we need to keep in mind

in the future as we organize training and support for

our teachers. We need to be sensitive for our online

teachers’ evolving needs and expectations relating to

the nature and content of the support.

6.2 Future Work

In the future, we continue studying our online

teachers’ experiences and perceptions on teaching.

The development of teachers’ technological

pedagogical content knowledge is one of the specific

topics we would like to investigate further. We would

also like to expand our studies to students’

experiences and perceptions of the content and

implementations of the online courses. Finally,

universities’ viewpoint and experiences of this kind

of jointly organized larger teaching modules would be

interesting to study in more detail.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank all the teachers who kindly answered our

questionnaire.

REFERENCES

ABS (Association of Business Schools Finland). 2017.

http://www.abs.fi/2017/02/03/opetus-ja-kulttuuriminis

terio-tukee-kauppatieteiden-opetusyhteistyota-yli-milj

oonalla-eurolla/ [retrieved 23.1.2018]

Baleni Z. 2015. Online formative assessment in higher

education: Its pros and cons. The Electronic Journal of

e-Learning, 13(4), 228-236.

Cook, D. 2007. Web-based learning: pros, cons and

controversies. Clinical Medicine. 7(1), 37-42.

Fedynich, La V. 2013. Teaching beyond the classroom

walls: The pros and cons of cyber learning. Journal of

Instructional Pedagogies. 13. 7 pages.

Hixon, E., Buckenmeyer, J., Barczyk, C., Feldman, L.

Zamojski, H. 2011. Beyond the early adopters of online

instruction: Motivating the reluctant majority. The

Internet and Higher Education, 15(2), 102-107.

Orr, R., & Williams, M. R., & Pennington, K. 2009.

Institutional Efforts to Support Faculty in Online

Teaching. Innov High Educ, 34, 257–268.

Rogers, E. M. 2003. Diffusion of innovations. New York:

Free Press. 5

th

edition.

Soffer, T., Nachmias, R., & Ram, J. 2010. Diffusion of web

supported instruction in higher education – The case of

Tel-Aviv University. Educational Technology &

Society, 13(3), 212–223.

Teachers’ Viewpoint on Online Courses

417