The MOF Perspective on Business Modelling

Berend T. Alberts, Lucas O. Meertens, Maria-Eugenia Iacob and Lambert (Bart) J. M. Nieuwenhuis

University of Twente, PO Box 217, Enschede, The Netherlands

b.t.alberts@student.utwente.nl, {l.o.meertens, m.e.iacob, l.j.m.nieuwenhuis}@utwente.nl

Keywords: Business Modelling, Business Models, Meta-business Models, Meta-object Facility.

Abstract: The business model field of research is a young and emerging discipline that finds itself confronted with the

need for a common language, lack of conceptual consolidation, and without adequate theoretical

development. This not only slows down research, but also undermines business model’s usefulness for

research and practice. We offer a new perspective on business modelling to address these issues. It looks at

business modelling from the perspective of the Meta-Object Facility, emphasising the role of models and

meta-models. From this new perspective, a commonality analysis can identify the important classes in

business modelling. This new perspective on business modelling helps to create a common language,

achieve conceptual consolidation and supports theory development; it addresses issues that hinder business

model research.

1 INTRODUCTION: A NEED FOR

BUSINESS MODEL THEORY

DEVELOPMENT

In general, a business model is a simple and, usually,

graphic depiction of a company, often using boxes

and arrows. It mostly describes a single company, a

group of companies, or part of a company. In the

broadest sense, a business model is an abstract

(which means simplified) representation of the

company, a “model of the business”. The business

model field of research is strongly growing and

maturing over the last decade, mostly since 2000

(Osterwalder, Pigneur & Tucci, 2005; Zott, Amit &

Massa, 2011). Since to this date no unified view

exists regarding its conceptual foundation, this

young and emerging discipline has been described

(Meertens, Iacob & Nieuwenhuis 2011) as “finding

itself in a state of prescientific chaos”, in the sense

of Kuhn (Kuhn 1970).

Practitioners using business models have a need

for a common language, especially since they come

from different disciplinary backgrounds: strategic

management, industrial organization, and

information systems (Pateli & Giaglis, 2004). In

addition, links to other research domains are

necessary to establish the business model field as a

distinct area of investigation (Pateli & Giaglis,

2004). However, researchers still have to build more

on each other’s work, and research generally

advances slowly and often remains superficial

(Osterwalder, Pigneur & Tucci, 2005).

Currently, researchers use different terms to

describe similar things, and the same term for

different things. Business model often means “a

model of a single company” and, specifically, of the

way a company does business, creates, and captures

value. However, other things are called business

model as well, for example when referring to a

pattern in the phrasing “...the freemium business

model...” In addition, ontologies or frameworks such

as the Business Model Ontology (BMO), e3-value,

RCOV or activity system are sometimes referred to

as a business model too (Osterwalder, 2004;

Gordijn, 2002; Demil & Lecoq, 2010; Zott & Amit,

2010). In our research, we refer to such frameworks

(BMO, e3-value, RCOV) as meta-business models.

We define these analogous to meta-models in

software or systems engineering (Van Halteren,

2003):

A meta-business model is the set of concepts that

is used to create business models. A business

model developed from this set of concepts is an

instance of the meta-business model.

For example, a meta-business model may define

that “a business model consists of a value

proposition, organization, and finances.” Thus, the

43

Alberts B., Meertens L., Iacob M. and Nieuwenhuis B.

The MOF Perspective on Business Modelling.

DOI: 10.5220/0004461000430052

In Proceedings of the Second International Symposium on Business Modeling and Software Design (BMSD 2012), pages 43-52

ISBN: 978-989-8565-26-6

Copyright

c

2012 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

meta-business model lays out the rules for modelling

a business model. Consequently, a business model is

an instance of the meta-model, following those rules.

An example of a meta-business model is the BMO

(Osterwalder, 2004), which can serve to make a

business model of any company. This business

model would be an instance of the BMO. However,

the BMO is itself also a model. It is a model for

creating business models. As such, it is a “business

model”-model or, in modelling terms, a meta-

“business model”.

Stimulating researchers to build more on each

other’s work can be achieved by developing

instruments for comparing different meta-business

models. This can also help the integration with

horizontally related concepts such as strategy and

processes (Gordijn, Osterwalder & Pigneur, 2005).

“...A conceptual framework will provide a basis for

business model theory development by providing a

structure from which researchers can debate,

recognize points of agreement and disagreement,

identify potential points of integration or linkage

along with areas of future research” (Lambert,

2008). Such a conceptual framework can help to

analyse shared or distinctive features of different

meta-business models (Lambert, 2008).

Consensus on the theoretical underpinnings of

the business model concept has not yet been

achieved (Al-Debei and Avison, 2010), which

undermines its applicability in different contexts.

“...The business model remains a theoretically

underdeveloped (and sometimes overloaded)

concept, which may raise doubts concerning its

usefulness for empirical research and theory

building” (Zott, Amit & Massa, 2011). For future

research, more clarity on the theoretical foundation

and conceptual consolidation is necessary (Zott,

Amit & Massa, 2011).

The articles referenced above are all review

articles, specifically aimed at providing an overview

of the status and developments of business model

research and the emergence of the discipline. In

short, the most important issues are:

• the need for a common language,

• lack of conceptual consolidation, and

• theoretical development of the concept.

These issues relate strongly to the different meta-

business models existing separately. Consequently,

using different meta-models may result in different

business models of the very same organization. This

can have severe consequences. For example, if a

business model is used in a requirements

engineering process, the resulting requirements can

vary greatly depending on which meta-business

model is used. Unfortunately, because of the gaps in

business model research, such problems are hard to

address currently.

Another area of research, software and systems

engineering, has more experience dealing with a

great variety of meta-models, and already addressed

the need for a generic framework to manage,

manipulate, and exchange these models. This

generic framework is the Meta-Object Facility

(MOF), created by the Object Management Group

(OMG) (1999). The MOF represents a layering of

meta-models for describing and representing meta-

data: data about other data (Van Halteren, 2003).

Although it originates from an object-oriented

software design domain, the MOF allows the

definition of (meta-) models independent of the

application domain.

In this paper, we introduce the MOF perspective

on business modelling. Introducing a new

perspective on business modelling helps identify

differences and commonalities of business

modelling languages and concepts. We use the MOF

to create a meta-meta-business model that promotes

further theory development. In doing so, we

contribute to advancing the discipline of business

modelling.

The structure of the paper is as follows. After

having presented the background and motivation in

this section, section 2 further explains the MOF.

Section 3 provides our main contribution: it applies

MOF to business modelling. In addition, it provides

examples for each of the layers. This includes

suggesting a meta-meta-business model and a

graphical example of this new model’s use. Section

4 discusses further research possibilities with the

introduction of MOF in business modelling. Finally,

section 5 shows how this addresses the presented

issues of business model research.

2 THE META-OBJECT

FACILITY (MOF)

The MOF was introduced above as a generic

framework for working with a great variety of

models and meta-models. This section clarifies the

concept. The central idea of MOF is that every

model is an instance of some meta-model in an

abstract layer above it. Hence, a business model is

an instance of a meta-business model. The other way

round, every meta-model provides a vocabulary for

Second International Symposium on Business Modeling and Software Design

44

creating models; these models are instances in an

abstract layer below it. Thus, a meta-business model

provides a vocabulary for creating business models.

The account of the MOF given here strictly

follows Van Halteren (2003). Modelling data in

terms of meta-data can continue indefinitely, in

theory, with an infinite number of meta-layers. The

MOF is defined as four layers only, M0 to M3, as

shown in Figure 1:

• Layer M0 – instances: an instance is the flat

data, which can describe a running system’s state.

This data is an instance of elements in the M1 layer.

• Layer M1 – models: the model provides the

vocabulary for the instance. For example, if the

instance is a running system, the model is its source

code. The model is itself an instance of the M2

layer.

• Layer M2 – meta-model: the meta-model

consists of generic elements used for description of

the model at the M1 layer. For example, having a

system’s source code at the M1 layer, the M2 layer

is a programming or modelling language such as

java or UML. While the M1 layer is an instance of

the M2 layer, this layer is again an instance of the

even more generic elements of the M3 layer.

• Layer M3 – meta-meta-model: the meta-meta-

model consists of the elements providing the most

generic vocabulary for the M2 layer. For example,

the M3 MOF model, can be used to describe a

language such as java or UML. While in theory an

infinite number of meta-layers exists, for our

purpose, we follow the M3 layer as standardized in

the OMG MOF specification, also called the MOF

model.

Figure 1: The MOF layers.

The MOF vocabulary comes from the context of

object-oriented formalism in software engineering

The MOF model itself consists of the following four

concepts:

• Classes: classes are the primary modelling

constructs. These are the central objects that interact

with one another. Classes can be organized

hierarchically in specializations or generalizations.

• Associations: associations are the relations

between any two classes. Such a relationship may

have a name, cardinality, and type.

• Data types: data types are the types used for

non-class objects. For example, commonly used data

types in the world of programming are integer and

string.

• Packages: packages are groups of classes and

are used to organize models and meta-models.

Packages can introduce complex interactions

between classes, such as nesting, inheritance, and

importing.

The MOF model is a generic meta-meta-model

that allows working with a diversity of meta-

business models. In using the MOF, ultimately every

(meta-) model is defined in terms of classes,

associations, data types, and packages. In our

attempt to relate business modelling to the MOF, we

identify classes only.

3 THE MOF AND BUSINESS

MODELLING

This section provides our main contribution: it

applies the MOF to business modelling, to create a

generic framework for business modelling that

provides conceptual consolidation, and helps with a

common language and further theory development.

The most important reason for using the MOF is the

perspective it provides on the practice of modelling.

First, subsection 3.1 shows how the MOF layers

encompass the business modelling concepts. Second,

subsection 3.2 provides general examples for each of

these layers. Third, subsection 3.3 treats the M2

layer. It addresses the issue of which classes should

be on this layer. Finally, subsection 3.4 shows

several components at the M1 layer.

3.1 Viewing Business Modelling from

the MOF Perspective

Applying the MOF layers to business modelling

leads to Figure 2. It shows how the MOF layers

encompass the concepts of business modelling. It is

analogous to Figure 1. Every (business) model is an

instance of a meta-model from the above layer.

Applying this notion in terms of the MOF layers, as

shown in Figure 2, leads to the following layers for

business modelling:

• Layer M0 – business model instance: the

central construct of this research area is a business

The MOF Perspective on Business Modelling

45

Figure 2: The MOF layers applied to business modelling.

• model instance, which can describe an

organization, situation, or pattern. This business

model instance is an instance of elements in the M1

layer.

• Layer M1 – meta-business model: the meta-

business model provides the vocabulary for the

business model instance. The meta-business model

is itself an instance of the M2-layer. Since the

instance data is a model already, the terms change

compared to the MOF model. In this case, the model

from MOF is a meta-business model.

• Layer M2 – meta-meta-business model: the

meta-meta-business model consists of generic

elements used for description of the meta-business

model at the M1 layer. While the M1 layer is an

instance of the M2 layer, this layer is again an

instance of the even more generic elements of the

M3 layer.

• Layer M3 – MOF model: the MOF model

consists of the elements providing the most generic

vocabulary for the M2 layer. This is the same model

as the top layer of MOF (Figure 1). The MOF model

defines every instance in terms of classes,

associations, data types, and packages.

The above description shows that the concepts of

business modelling and meta-business models fit

effortlessly in the MOF layers. This indicates that

the MOF is indeed a generic framework, which

works for any form of models and meta-models.

3.2 Simple Examples for Each Layer

Starting from the bottom up, many possible

examples exist at the M0 layer for business

modelling. Business model instances belong in this

layer, therefore, any business model that describes

an organization, situation, or pattern would fit here.

An example of a real life case is U*Care, a service

platform for elderly care (Meertens, Iacob &

Nieuwenhuis, 2011). Other examples of a business

case as business model instances are two models of

the clearing of music rights for internet radio

stations (Gordijn, Osterwalder & Pigneur, 2005),

and modelling of the development of Arsenal FC

over a period of eleven years (Demil & Lecoq,

2010). A pattern, such as “freemium”, also belongs

on the M0 layer (Osterwalder, 2010).

At a higher level of abstraction, the M1 layer

contains the meta-business models. They provide the

vocabulary for the business model instances.

Previously often called frameworks or even

ontologies, examples of meta-business models are

plentiful. For example, the music rights case is

modelled in two different meta-business models, e3-

value and the BMO (Gordijn, Osterwalder &

Pigneur, 2005). The Arsenal FC case is modelled

using the meta-business model RCOV (Demil &

Lecoq, 2010).

Figure 3 in subsection 3.4 provides

more examples, while focussing on their

components.

Since this is the first time the M2 layer is

recognized in business modelling, nobody has

presented examples as such at this layer yet.

Following the MOF perspective, the M2 layer

contains a meta-meta-business model that provides a

vocabulary for meta-business models at the M1

layer. This means that such a meta-meta-business

model must consist of generic elements that capture

meta-business models, such as the BMO, e3-value,

and RCOV. Literature that presents a review of

business modelling research, such as Zott, Amit and

Massa (2011), suggest those generic elements. In

subsection 3.3, we propose classes for a

meta-meta-business model (M2BM) that belongs on

the M2 layer.

At the top of the pyramid, the M3 layer has only

one example in our case. It is the MOF model itself,

which we have explained in Section 2 already. It

Second International Symposium on Business Modeling and Software Design

46

includes classes, associations, data types, and

packages.

3.3 Specifying Classes at the M2 Layer

While an interpretation of business modelling in

MOF terminology provides conceptual

consolidation, a meta-meta-business model at the

M2 layer would provide a common language for

business modelling. The meta-meta-business model

would be overarching the meta-business models.

This subsection researches what is necessary to

create such an overarching meta-meta-business

model.

First, 3.3.1 presents what type of elements should

be in the meta-meta-business model. Second, 3.3.2

explains how to obtain these elements. Third and

final, 3.3.3 suggests several of these elements in the

form of classes.

3.3.1 What Should Be in the

Meta-Meta-Business Model?

Business modelling is the act of creating a business

model instance; this is an instance of a meta-

business model. The instance is a M0 layer model,

the meta-business model is a M1 layer concept.

Many of these meta-business models exist already,

some with a strong link to information systems,

others closely related to strategic management or

industrial organisation. For example, Vermolen

(2010) identified nine such meta-business models

published in the top 25 MIS journals. The Business

Model Ontology from Osterwalder (2004) was also

mentioned previously.

All meta-business models, as M1 models, must

follow some sort of guidelines defined at the M2

layer. The generic rules for meta-business model

should be defined at the M2 layer as a meta-meta-

business model: M2BM (M2 both for MOF M2

layer and for meta-meta-). Such a meta-meta-

business model does not exist yet; however, as the

introduction shows, creating it is exactly what

different researchers in the business model discipline

are asking for.

The different meta-business models at the M1

layer give the first hint of what this meta-meta-

business model looks like. Every model at the M1

layer must be an instance of more generic elements

at the M2 layer. The meta-meta-business model

must consist of such concepts that it allows the

creation of any model that can be regarded as an M1

meta-business model.

The required coverage of M2 classes can be

discovered with a commonality analysis amongst

different meta-business models. For example, all M1

meta-business models propose some set of

components, so one of the classes of the M2 meta-

meta-business model should be components.

Several researchers have in fact performed such

commonality analyses. We argue that the abstract

meta-meta-business model that belongs on this layer

should come from review literature on meta-

business models. As a review synthesizes the

concepts used in business modelling literature, the

resulting concepts can be considered instances of

classes from the M3 layer.

3.3.2 Review Literature on Business

Modelling

An extensive literature survey identified five articles

that can aid us in finding out what classes make up

the M2 meta-meta-business model. The method we

followed consisted of three steps. The first step was

a search on Scopus and Web of Science for relevant

articles published between 2000 and august 2011,

using two queries:

• in title: “business model*”

• in title-keywords-abstract: “business model*”

AND ontology OR ((framework OR e-commerce)

AND (design OR analysis))

All results were checked for relevance by

analysing the abstract. The second step was an

analysis of the articles’ content for relevance,

searching for presentation of meta-business models,

or review of business model research or literature.

The third step was selecting those articles usable for

creating the M2 meta-meta-business model. Table 1

presents the resulting five articles.

Table 1: Overview of business model review literature.

Authors Title Year

Pateli and

Giaglis

A research framework for

analysing eBusiness models

2004

Gordijn,

Osterwalde

r and

Pigneur

Comparing two Business Model

Ontologies for Designing e-

Business Models and Value

Constellations

2005

Lambert A Conceptual Framework for

Business Model Research

2008

Al-Debei

and Avison

Developing a unified framework

of the business model concept

2010

Zott, Amit

and Massa

The Business Model: Recent

Developments and Future

Research

2011

The MOF Perspective on Business Modelling

47

Table 2: Classes for the M2 layer meta-meta-business model.

Pateli and Giaglis,

2004

Gordijn, Osterwalder

and Pigneur, 2005

Lambert, 2008 Al-Debei and

Avison, 2010

Zott, Amit and

Massa, 2011

Definition Definition Definition Definition

Purpose of the

ontology

Focus of the ontology

Actors using the

ontology

Other applications

Objective BM reach

BM Functions

Strategic marketing

Value creation in

networked markets

Strategy

Innovation

Components Ontology content and

components

Fundamentals

(elements)

V4 BM dimensions Components

Conceptual models Representation

Visualization

Fundamentals

(characteristics of

representations)

Representations

(display)

Representations

Change methodology Change methodology

Evaluation models Evaluation methods

for business model

instances

Operational

(measurement)

Firm performance

Origins Emergence

Design methods and

tools

Adoption factors

Supporting

technologies

Tool support

Modelling principles

Taxonomies Classification Operational

(recognition)

Typologies

These five articles present a number of concepts

that the authors consider important in business

modelling. Pateli and Giaglis (2004) identify eight

streams of research in business modelling. Gordijn,

Osterwalder and Pigneur (2005) compare the

Business Model Ontology and e3-value on a number

of criteria. Lambert (2008) creates a business

modelling framework based on a conceptual

framework from the domain of accounting. Al-Debei

and Avison (2010) identify four facets of business

modelling. Zott, Amit and Massa (2011) provide the

most up to date overview of the state of art of

business modelling research.

3.3.3 Classes of the M2BM:

A Meta-Meta-Business Model

Table 2 identifies the important concepts in business

modelling according to the review literature. It is a

first indication of possible classes for the M2BM. A

comforting result is that there is quite some overlap

in the identified classes. For example, four of the

five articles name definition, and all have

components. This allows for mapping of the

concepts on to each other to get to a compact list of

classes. Already,

Table 2 provides an attempt at this.

While in some cases this mapping is obvious (as for

definition and components), it remains

interpretative. As section 4.2 discusses, two concepts

were left out of

Table 2 deliberately: ontological role

and ontology maturity & evaluation. Both from

Gordijn, Osterwalder and Pigneur (2005). The table

suggests which classes are important to business

modelling.

3.4 Example Use of M2BM:

Components of Meta-Business

Models

This section presents an example of the M2BM’s

use in business modelling. The core construct of

business modelling is probably the very visible

components of meta-business models. This example

provides a comparison of ten different meta-business

models based on their components. It shows how

several meta-business models all have their own

instantiation of the M2BM class components.

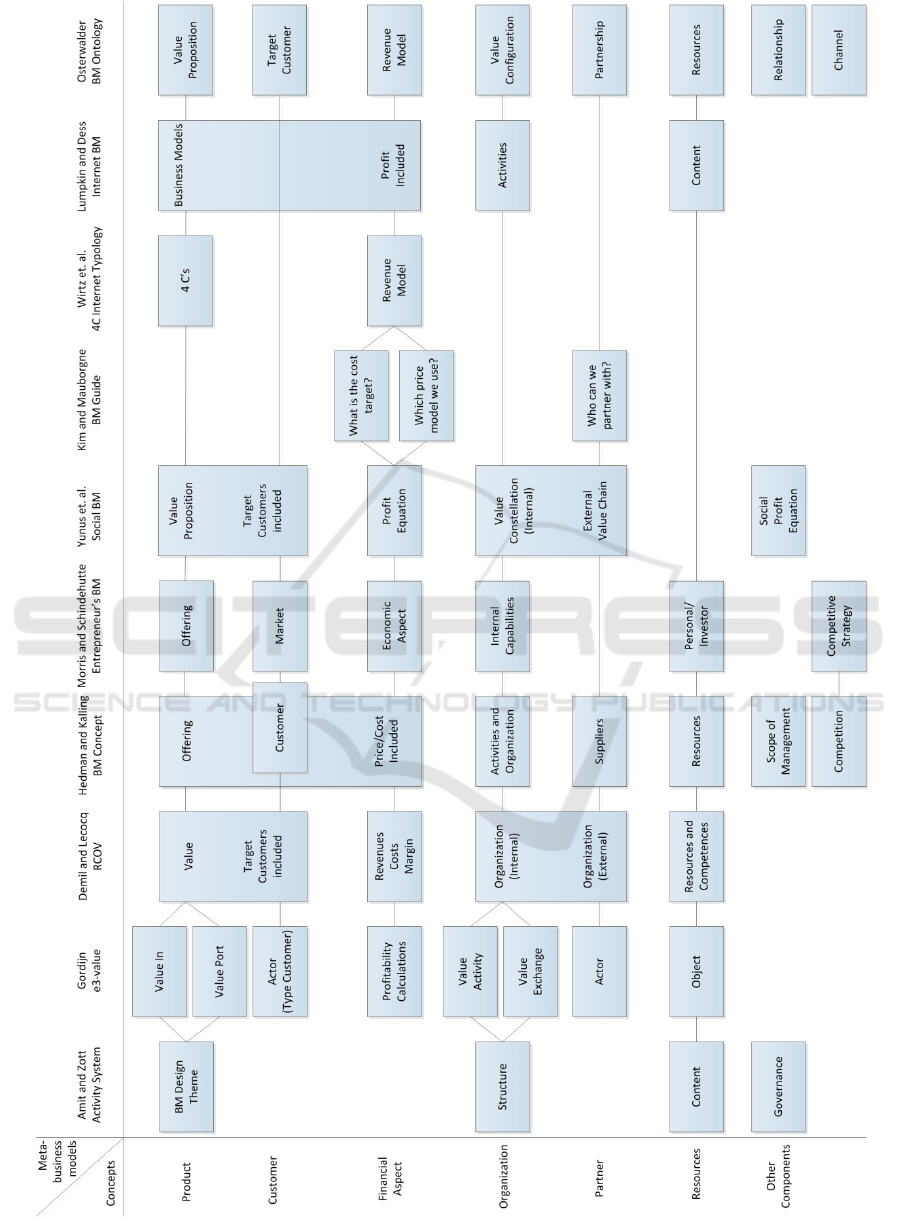

Figure

3 is the result of the comparison (Alberts, 2011).

The first nine meta-business models are those

identified by Vermolen (2010), published in the

top 25 MIS journals. The tenth has also been

Second International Symposium on Business Modeling and Software Design

48

Figure 3: Comparison of M1 layer meta-business model components (adapted from Alberts (2011)).

The MOF Perspective on Business Modelling

49

mentioned already, Osterwalder’s (2004) Business

Model Ontology.

1. Activity system by Zott and Amit (2010).

2. e3-value by Gordijn (2002).

3. RCOV by Demil and Lecocq (2010).

4. The BM concept by Hedman and Kalling

(2003).

5. Entrepreneur’s BM by Morris, Schindehutte and

Allen (2005).

6. The social BM by Yunus, Moingeon and

Lehmann-Ortega (2010).

7. The BM guide by Kim and Mauborgne (2000).

8. 4C Wirtz, Schilke and Ullrich (2010).

9. Internet BM by Lumpkin and Dess (2004).

10. BMO by Osterwalder (2004).

Figure 3 identifies the components used in the

above articles. It is an indication of possible

components for meta-business models. Quite some

overlap exists in the identified components, which

allows for mapping of the concepts on to each other.

Already,

Figure 3 provides an attempt at this. While

in some cases this mapping is obvious, it remains

interpretative. However, the figure still suggests

which components are important to business

modelling.

4 DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study is to promote theory

development by viewing the concepts of business

modelling in light of the Meta-Object Facility.

Besides an open review of what the MOF allows,

this section also comments on the classes left out of

the B2BM.

4.1 Uses for the MOF Perspective on

Business Modelling

Our main reason for using the MOF is the

perspective it offers on the practice of modelling. As

such, we have only identified classes in the M2

Layer meta-meta-business model. Still, it has

become very clear that the discipline of business

modelling allows for use of the MOF, and that the

concept of meta-models can be of great assistance.

We believe this introduction of MOF in business

modelling has only scratched the surface of what is

possible. Take for example an association between

two classes: the scope of what is being modelled will

strongly influence which components are important.

Defining the M2BM in terms of the MOF model

concepts allows formalization of business modelling

that promotes its use in requirements engineering

and software development. In the same line of

reasoning, the MOF perspective may provide a new

chance to match business modelling and UML. So

far, literature that uses both the terms “UML” and

“business modelling” focuses on process modelling,

not on business modelling. Another application of

UML in this domain is creating a reference ontology

(Andersson et al., 2006). This reference ontology

allows model transformations between Resource-

Event-Agent (REA), e3-value, and BMO. Such

reference ontology may provide useful methods for

the M2BM.

The MOF opens a rich new view on business

modelling. So far, we have only looked at one

aspect: the possible classes of the M2BM. There are

still many more possibilities in using the MOF to

approach business modelling.

4.2 Classes Left out of the M2BM

Two potential classes were left out of Table 2. They

are ontological role, and ontology maturity &

evaluation. Both concepts come from Gordijn,

Osterwalder and Pigneur (2005). We argue that

these two concepts are not suitable as classes for a

meta-meta-business model.

The ontological role does not fit, as it is very

similar to the entire concept of the MOF. As such, it

has no place within one of the layers. For

ontological role, Gordijn, Osterwalder and

Pigneur (2005) define three levels: operational data

at Level L0, ontology at Level L1, and ontology

representation language at Level L2. Operational

data is similar to what we call a business model

instance at layer M0. Ontology is similar to what we

call a meta-business model at layer M1. Finally, an

ontology representation language is similar to the

M2BM at layer M2.

Ontology maturity & evaluation does not fit, as it

is itself not meta-data describing a meta-business

model. Rather, checking maturity could be a use of

the M2BM. For example, the maturity of a meta-

business model could be scored based on how many

of the M2BM classes it implements.

5 CONCLUSIONS

This article uses MOF to provide a new perspective

on business modelling. This contributes to business

modelling on three important issues:

Second International Symposium on Business Modeling and Software Design

50

• the need for a common language,

• lack of conceptual consolidation, and

• theoretical development of the concept.

Introducing the MOF perspective provides

conceptual consolidation in business modelling. The

MOF is used to take a different perspective on the

meta-business models, which makes it possible to

find commonalities. Identification of the M2BM

classes illustrates this. In addition, existing

definitions of “business model” can be positioned on

the layers. This provides better options to compare

definitions.

The M2BM on the M2 layer provides a common

language for business modelling. In business

modelling literature, many authors have their own

vocabulary. In creating the M2BM, we show that

different terms often refer to a single concept.

Approaching the different meta-business models

from a higher MOF layer addresses this issue. Doing

so allows building on the strengths of the meta-

business model original domains: strategic

management, industrial organization, and

information systems. Using the MOF, and especially

the M2BM as a common language, helps overcome

the differences of these domains and focus on

commonalities.

Finally, theoretical development of the business

model concept is promoted, as the MOF opens up a

wide range of research possibilities for business

modelling. Placing the concept of business model in

the frame of the MOF allows for further theory

development, both within the discipline and in

relation to other domains. It serves as a navigational

landmark for business model research when relating

it to existing material. Additionally, it helps to create

bridges to other research areas, especially when

relating to other modelling domains.

Future research must specify a M2BM with

classes, and possibly relations, data-types, and

packages. This common language will define

business modelling. The M2BM presented in this

article is a first draft; as such, it requires more work.

However, even in this rough form it shows that the

MOF is a rich addition to the business modelling

discipline.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work is part of the IOP GenCom U-CARE

project, which the Dutch Ministry of Economic

Affairs sponsors under contract IGC0816.

REFERENCES

Al-Debei, M.M., Avison, A., 2010. Developing a unified

framework of the business model concept. European

Journal of Information Systems, 19(2010), pp.359–

376.

Alberts, B. T., 2011. Comparing business modeling

methods: creating and applying a comparison

framework for meta-business models. In Proceedings

of the 14

th

Twente Student Conference on IT. Twente

Student Conference on IT. Enschede, Netherlands:

University of Twente.

Andersson, B., Bergholtz, M., Edirisuriya, A., Ilayperuma,

T., Johannesson, P., Gordijn, J., Gregoire, B., Schmitt,

M., Dubois, E., Abels, S., Hahn, A., Wangler, B.,

Weigand, H., 2006. Towards a Reference Ontology for

Business Models. In Proceedings of the 25

th

International Conference on Conceptual Modeling.

International Conference on Conceptual Modeling.

Demil, B., Lecocq, X., 2010. Business Model Evolution:

In Search of Dynamic Consistency. Long Range

Planning, 43(2010) pp.227-246.

Gordijn, J., 2002. Value-based Requirements Engineering:

Exploring Innovative e-Commerce Ideas. PhD Thesis.

Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam.

Gordijn, J., A. Osterwalder, Pigneur, Y., 2005. Comparing

two Business Model Ontologies for Designing e-

Business Models and Value Constellations. In

Proceedings of the 18

th

Bled eConference:

eIntegration in Action. 18th Bled eConference

eIntegration in Action. Bled, Slovenia.

Halteren, A. T. van, 2003. Towards an adaptable QoS

aware middleware for distributed objects. PhD Thesis.

University of Twente.

Hedman, J., Kalling, T., 2003. The business model

concept: Theoretical underpinnings and empirical

illustrations. European Journal of Information

Systems, 12(1) pp.49-59.

Jasper, R., Uschold, M., 1999. A Framework for

Understanding and Classifying Ontology Applications.

Proc.12th Int. Workshop on Knowledge Acquisition,

Modelling, and Management (KAW'99), University of

Calgary, Calgary, CA, SRDG Publications.

Kim, W.C., Mauborgne, R., 2000. Knowing a winning

business idea when you see one. Harvard Business

Review, 78(5) pp.129-138, 200.

Kuhn, T., 1970. The structure of scientific revolutions (2

nd

ed.), University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Lambert, S., 2008. A Conceptual Framework for Business

Model Research. In Proceedings of the 21

st

Bled

eConference: eIntegration in Action. 21

st

Bled

eConference eCollaboration: Overcoming Boundaries

through Multi-Channel Interaction. Bled, Slovenia.

pp.227-289.

Lumpkin, G.T., Dess, G.G., 2004. E-Business Strategies

and Internet Business Models:: How the Internet Adds

Value. Organizational Dynamics, 33(2) pp.161-173.

Meertens, L. O., Iacob, M. E., Nieuwenhuis, L. J. M.,

2011. Developing the Business Modelling Method. In

Proceedings of the First International Symposium on

The MOF Perspective on Business Modelling

51

Business Modeling and Software Design, BMSD

2011, Sofia, Bulgaria. pp.103-110.

Morris, M., Schindehutte, M., Allen, J., 2005. The

entrepreneur's business model: toward a unified

perspective. Journal of Business Research, 58(6)

pp.726-735.

Object Management Group, 1999. Meta Object Facility,

Version 1.3, OMG document ad/99-07-03.

Osterwalder, A., 2004. The Business Model Ontology – a

proposition in a design science approach. PhD Thesis.

Universite de Lausanne.

Osterwalder, A., Pigneur, Y., 2010. Business Model

Generation: A Handbook for Visionaries, Game

Changers, and Challengers, John Wiley & Sons.

Osterwalder, A., Pigneur, Y., Tucci, C. L., 2005.

Clarifying Business Models: Origins, Present, and

Future of the Concept. Communications of AIS,

15(May), pp.2-40.

Pateli, A. G., Giaglis, G. M., 2004. A research framework

for analysing eBusiness models. European Journal of

Information Systems, 13(4), pp.302-314.

Vermolen, R., 2010. Reflecting on IS Business Model

Research: Current Gaps and Future Directions. In

Proceedings of the 13

th

Twente Student Conference on

IT. Twente Student Conference on IT. Enschede,

Netherlands: University of Twente.

Wirtz, B.W., Schilke, O. and Ullrich, S. 2010. Strategic

Development of Business Models. Implications of the

Web 2.0 for Creating Value on the Internet. Long

Range Planning, 43(2010) pp.272-290.

Yunus, M., Moingeon, B., Lehmann-Ortega, L., 2010.

Building Social Business Models: Lessons from the

Grameen Experience. Long Range Planning 43(2010)

pp.308-325.

Zott, C., Amit, R. 2010. Business Model Design: An

Activity System Perspective. Long Range Planning,

43(2010) pp.216-226

Zott, C., Amit, R., Massa, L., 2011. The Business Model:

Recent Developments and Future Research. Journal of

Management, 37(4), pp.1019-1042.

Second International Symposium on Business Modeling and Software Design

52