EVALUATING ENGAGEMENT TO ADDRESS

UNDERGRADUATE FIRST YEAR TRANSITION

A Case Study

Clive Holtham

1

, Rich Martin

1

, Ann Brown

1

, Gawesh Jawaheer

2

and Angela Dove

1

1

Cass Business School, City University, 106 Bunhill Row, London, EC1Y 8TZ, U.K.

2

School of Health Sciences, City University, Northampton Square, London, EC1V 0HB, U.K.

Keywords: Student Engagement, Learning Analytics, Learning Design, Moodle.

Abstract: Rapidly changing demands from employers of students of business meant substantial redesign of the first

year undergraduate experience whose underlying pedagogy drew on the concept of “high-engagement”

learning. This paper focuses on the question of how engagement can be evaluated. It is argued that a variety

of “sensors” are needed for evaluation, both quantitative and qualitative. Of particular interest is the use of

Moodle logs as an emerging powerful sensor.

1 INTRODUCTION

Nicol (2006) summarises the particular importance

of the undergraduate first year and relates it to the

use of formative assessment, which, he argues has

considerable potential to enhance students’

subsequent experience.

This case study examines an innovative

undergraduate first year core module which

explicitly aimed to create through its learning design

high levels of student engagement (Cass Business

School, 2010). These high levels were planned to be

achieved through the design of learning activities

which were both electronic and non-electronic.

During the development phase of the project,

consideration was given as to how engagement

might be measured and evaluated. It was planned at

that time to use a mixed method, including a weekly

meeting of tutors, and heavy utilisation of the

Reports feature of the Moodle virtual learning

environment. A pilot was carried out in a small

elective module, and ways were found to track

engagement using the standard Moodle reports. But

it was also found to be time consuming and to be

unlikely to scale.

The assumptions explicit in the design of the

module were:

(a) the transition from high school to university

was becoming more problematic

(b) the core theory of engagement was Chickering

and Gamson’s (1987) long-standing framework

(c) the approach should be based on high-touch as

well as high tech (Naisbitt, 1999) through much

more extensive and intensive use of the virtual

learning environment

(d) a cross-university initiative in 2010 in learning

analytics had highlighted the potential of a data-

driven approach to high-touch interaction, and

new Moodle analytic facilities specifically for

this module were commissioned from the

Health Science School learning analytics

research team.

2 RESEARCH METHOD

The main body of empirical work undertaken and

reviewed here took place over a one year period

(2010-2011). The approach taken is participatory

and collaborative action research (Stringer, 1996).

The data sources which form the empirical

evidence base and that have been used to generate

and interrogate theory includes: our own reflexive

narratives in response to the developing work; the

textual material contained in the online collaboration

forums of the module tutors, the Moodle log data of

student activities, an online survey of the module

tutors, a sample of classroom interaction using

personal response systems, and a student focus

group.

223

Holtham C., Martin R., Brown A., Jawaheer G. and Dove A..

EVALUATING ENGAGEMENT TO ADDRESS UNDERGRADUATE FIRST YEAR TRANSITION - A Case Study.

DOI: 10.5220/0003925002230228

In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU-2012), pages 223-228

ISBN: 978-989-8565-06-8

Copyright

c

2012 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

3 ENGAGEMENT

Although motivation is one important factor in

engagement, engagement also relates to the level of

achievement. Perhaps the clearest identification of

high engagement is from Csikszentmihalyi (2002),

who applied his concept of “flow” to the educational

process. Astin (1993) reported that student

engagement is a key predictor of success in higher

education. Krause (2003) in turn suggested that

effective first year engagement involved students in

self-reflection in their first year at university. The

decision in the case discussed to move from earlier

VLEs was connected with a move towards greater

student engagement (Holtham & Courtney, 2006).

Kearsley and Shneiderman (1999), taking a

technology-orientated perspective, argue for

engagement theory as a basis for the use of new

technology to make new approaches possible. In the

event, the high-level group gave most weight to

Chickering and Gamson’s (1987) principles of good

practice in undergraduate education. These are in

effect a manifesto for a high-engagement approach

to learning, as opposed to a scientific framework.

1. encourages contact between students and

faculty,

2. develops reciprocity and cooperation among

students,

3. encourages active learning,

4. gives prompt feedback,

5. emphasizes time on task,

6. communicates high expectations, and

7. respects diverse talents and ways of learning.

A decade ago, we anticipated that proactive use

of a virtual learning environment would naturally

promote high engagement. Sadly, as identified by

JISC Digital Media (2011), much use of virtual

learning environments, including Moodle, is simply

as a content repository and assignment uploading

facility (Lane, 2009).

This narrow use is perhaps particularly

disappointing in Moodle, whose espoused

philosophy is avowedly social constructivist

(Moodle.org, 2011), embodying a change in role of

teacher from away from purely being a source of

knowledge. A text on Moodle as a business

(Henrick, Cole and Cole, 2011) stimulated in us the

conception that a VLE such as Moodle also had the

potential to provide the engine for a workflow

system, which could be used educationally.

The development of the module, drawing

together three separate modules was a complex task

and a fluid working group structure was developed

to ensure that as transparent an approach as possible

was taken to design and implementation. The design

team included an experienced learning designer at

professorial level who operated as both coach and

technical developer throughout the module itself.

This was in addition to school and programme-based

expertise in e-learning, without which an enterprise

of this nature could not have been contemplated.

At the time of selection of Moodle, radical

alternatives to a VLE were considered, such as a

personal learning environment (PLE) and generic

social media. Both of these are still under

consideration, but would at the most represent

augmentation above the VLE, rather than its

replacement.

The technological dimension was deeply

embedded in the module design, and symbolised by

the phrase high-tech/high-touch (Naisbitt, 2009).

One of our ongoing areas of pedagogic research is

into generational dimensions of learning and

technology (Rich, 2008), and current first year

students expect to engage with contemporary

technologies within their learning experience.

More particularly, in a first year first term

module, there is a particular concern about

identifying “at risk” students, who may not in

practice be participating, and a strong emphasis was

placed on promoting physical attendance and on

monitoring participation.

4 LEARNING ANALYTICS

The generic importance of analytics in learning had

been brought home to two members of the

development team who were in parallel also

involved in researching a large scale adult education

informal learning project, which was entirely web-

based and made very heavy use of web analytics to

track engagement of its audience of learners. There

was also familiarity in the development team with

web analytics being used widely in business. So the

team became interested in the potential for moving

beyond the minimally featured Moodle Reports, and

contact was made with the Health Sciences School

of the university where there was expertise in

Moodle analytics and in the mining of very large

datasets (Jawaheer et al, 2011).

Learning analytics is a very fast growing field,

with a lively leading-edge community promoting the

sharing of experience and the collective acceleration

of both theory and practice (Macfadyen & Dawson,

2010, Brown, 2011. Romero; (2010) outlines eleven

distinctive domains of the learning analytics

CSEDU2012-4thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

224

literature; this paper only relates to three of those

areas: Providing feedback for supporting instructors;

detecting undesirable student behaviours; and

constructing courseware.

A substantial body of work on VLE analytics is

beginning to emerge, and some of this (eg Urwin,

2011) is as with ourselves, concerned not simply

with retrospective historical tracking, but with what

we call “Action Support” that is, with learning

quickly and then taking direct action as a

consequence with the current cohort of students.

With a primarily face-to-face module, much of

the assessment of engagement would need to be

based on the two personal observation sensors,

physical and digital. Log data has proved to be

enormously helpful, but it does not relate to the

actual content, eg what is asked or said within a

discussion forum. We found difficulties in trying to

develop measures for each of the 7 principles. In

some ways though tutors felt that they could assess

engagement as a whole for their groups, for the

individual teams, and to some extent for individual

students.

5 RESEARCH PROJECT

FRAMEWORK

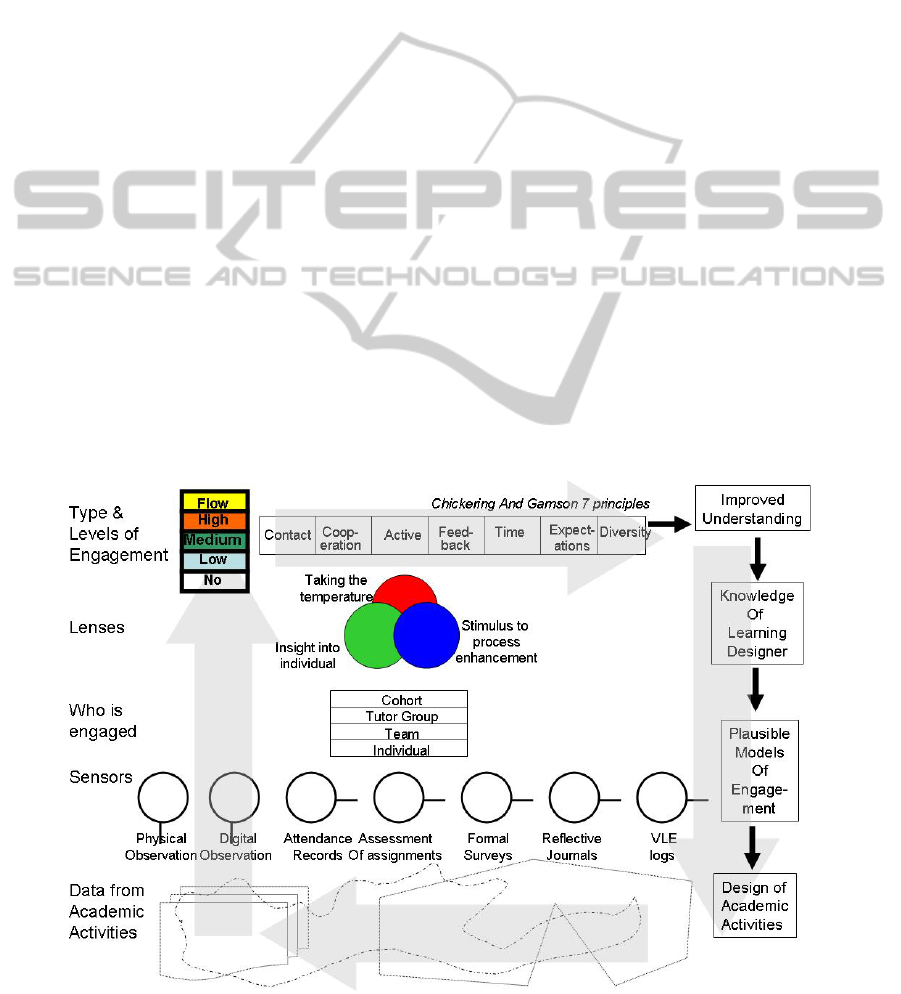

As the start of the module came closer, it was

essential from a research point of view to articulate

the parameters of the research project. The final

expanded framework is a layered model (Figure 1,

next page), where engagement is measured through

a number of “lenses”. The lowest layer is the vast

mass of data which derives from unfolding everyday

experiences of both students and teachers. This takes

many diverse forms - hard and soft; objective and

subjective; physical, digital and mental; explicit and

tacit; text and non-text, and the amount of such data

readily available in digital form has increased

considerably. However this increase does not

necessarily lead to more information and particularly

to more knowledge and insight. Our layered model

is built around a number of questions:

What is engagement? We have already

indicated our own use of the Chickering and

Gamson framework, augmented by the idea of

"flow" as indicating an extraordinarily high level of

engagement.

About whom can we evaluate engagement? In

the context of the present case study, we clearly

identified four levels - the cohort as a whole, the 6

tutor groups, the 24 teams and the 120 individual

students.

What are the lenses through which we choose

to evaluate engagement? In our case, we had

identified three lenses - taking the temperature,

insight into individuals, and searching for stimuli for

process improvement. This is the layer where

Figure 1: The full framework.

EVALUATINGENGAGEMENTTOADDRESSUNDERGRADUATEFIRSTYEARTRANSITION-ACaseStudy

225

information gets transformed into knowledge, and

also where the issue of plausible outcomes is

discussed.

In the case study "the seven sensors" for

gathering information were identified:

1. Observation and dialogue - physical

2. Observation and dialogue - digital

3. Assessments of student work

4. Attendance records

5. Formal surveys of students

6. Reflective journals

7. Virtual learning environment logs

We also regard sensors 1 and 2, direct

observation and dialogue (whether physical or

digital), as the "primary" sensors, due to their being

able to offer both broader and deeper sensing than

the other "secondary" sensors.

In this case study, very extensive use was made

of reflective journals, particularly proactive use was

made of attendance records, and there was slightly

above average use of formal student surveys. For us,

the major new sensor were the Moodle logs.

By the start of the module, the three lenses for

evaluation of engagement had been decided. Two of

these, relating to "overall temperature" and

"individual insight" might be found on any module

anywhere. However the third, "stimulus to

improvement" was a very specific function of being

a wholly new module run operated using a variety of

features which were distinctive to those involved.

The improvement lens potentially applies to any

of the levels of measurement, while the other two

relate to overall and specific levels respectively.

Moodle’s constructivist philosophy and emphasis on

learning communities makes it relatively weak in

organising reports by tutor group and team, and

much of the measurement customisation effort

related to generating "temperature" level reports.

Even within a single module, student

engagement can and perhaps should be defined in a

wide variety of ways. Despite the intrinsic difficulty

of measuring engagement, the course team was able

to identify five broad categories representing levels

of engagement. The highest and lowest of these were

fairly straightforward to identify, the highest

drawing on the concept of "flow". Whether in group

or individual work, it is generally not difficult to

observe flow. It does not mean all those with the

highest marks achieve flow - flow relates also to

fulfilling potential. A modest student may more than

fulfil their talents if they can achieve flow. A strong

student may get excellent marks without flow.

At the lowest level, non-engagement is a student

who rarely if ever shows up physically, rarely or

ever contributes online where the contribution is

voluntary, and often shows a lack of understanding

about even when and where the module is taking

place or what resources need to be consumed.

6 ACTIONABLE INTELLIGENCE

Regardless of the type of institution, learning

analytics almost encapsulates or symbolises a move

from a medieval (or at best nineteenth century)

lecture-based transmissive approach, to one that

embodies the idea of the academic as a facilitator of

learning, using a breadth of media both physical and

digital.

Good data alone is not sufficient: it needs to be

disseminated to the right people and to feed into

decision-making. Learning Analytics cannot be

divorced from the ongoing organisational pressures

and time shortages, and is most likely to be used if it

feeds into worthwhile actions (Campbell et al,

2007).

We also need to recognise that a trace is not the

same as the object or experience that made the trace.

Furthermore, some students prefer a static version of

resources due to their learning styles and time

management approaches; adding new links and

resources is not seen as beneficial by all.

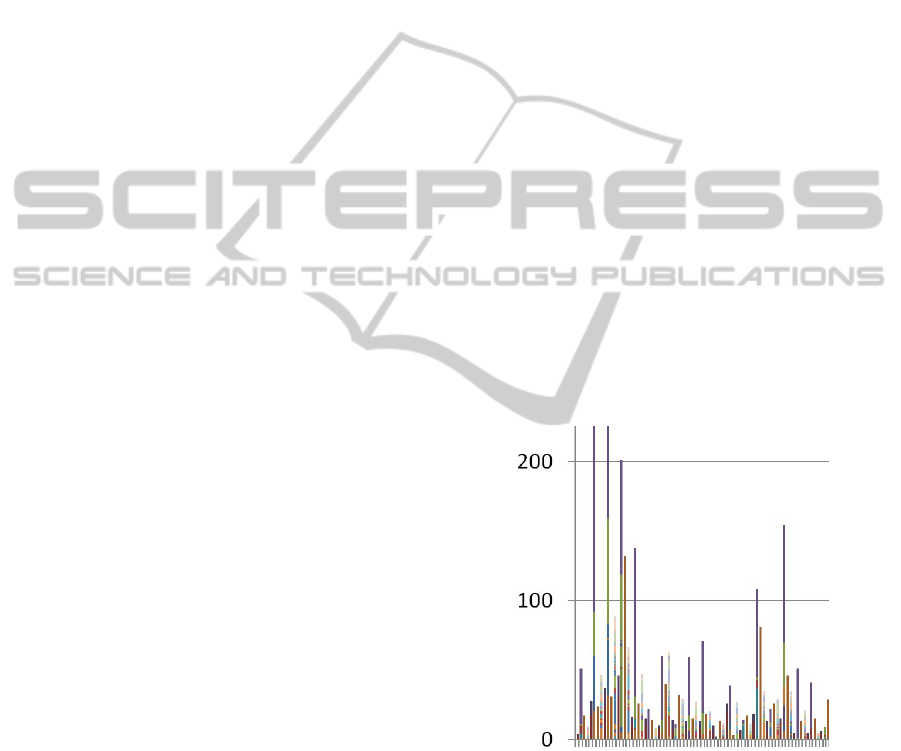

Figure 2: Custom learning analytics: individual student

cumulative graph.

Actionable intelligence – Taking the

temperature

This involved daily participation statistics that

showed low usage, which caused concern and led to

development of a new mandatory Moodle “lesson”.

Actionable intelligence – Continuous

Improvement

Even basic Moodle reports enabled us to track

CSEDU2012-4thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

226

the views of each resource. An “activity report” on

library resources showed there was a good

immediate take-up for some sources. But Business

Source Complete, the key database resource, had

hardly been looked at, and this was the impetus for

urgent creation of a library discussion forum.

Actionable intelligence – Individual insight

The course team was preoccupied with students

making zero or very low contributions, both in

general and for specific online resources. A Moodle

report was used to identify students who had never

accessed the FAQ Forum, which we regarded as a

key indicator of engagement. Tutors used this data to

follow up with their own tutees in the “at-risk”

group the question of non-participation. Figure 2

represents a custom report on individual student

activity, produced via direct access to Moodle logs,

rather than via the standard Moodle reports.

7 CONCLUSIONS

After the end of the module, we reviewed how far

the 5 levels of engagement (no, low, medium, high

and flow) might inter-relate with the 7 sensors. The

interest was in how different sensors were able to

support the evaluation of different levels of

engagement. This opens the possibility of a

dashboard to support learning design relating to

engagement. The results are shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Sensors related to engagement levels.

It is well understood that attendance records are

a very limited tool for assessing engagement. But

they are quite a powerful and easy to use tool for

picking up non-engagement. VLE logs are also

useful in measuring zero and low levels of

engagement. But simply accumulating clicks in the

VLE rarely related to the highest level of

engagement. Indeed some of the students with

extremely high levels of VLE used appeared over-

anxious in their approach generally. Some

concluding reflections were:

1. We combined both computer and non-

computer based evaluations of engagement eg tutor's

opinion, as done in any module

2. We have extended this, both by the design of

the VLE and then the use of basic plus enhanced

metrics using VLE activity logs and we have used

other electronic methods such as survey and

clickers.

3. Our focus on evaluating engagement has

helped us to redesign learning activities within the

module, better to address Chickering and Gamson’s

definitions of engagement.

REFERENCES

Astin, A., (1993) What Matters in College? Four Critical

Years Revisited. Josey-Bass: San Francisco, CA

Brown, Malcolm (2011) Learning Analytics: The Coming

Third Wave Educause Learning Initiative Brief,

Educause,

Campbell, J. P., DeBlois, P. B., & Oblinger, D. G. (2007).

Academic Analytics: A New Tool for a New Era.

Educause Review, 42(August 2007), 40-57

Cass Business School (2010) “Transition issues and

creating a student community stemming from

Undergraduate Review – 1 year on report: Issues for

Cass Undergraduate Programme” Cass Board of

Studies Report, 2010

Chickering, A. W., & Gamson, Z. F. (1987). Seven

Principles of Good Practice in Undergraduate

Education. AAHE Bulletin

Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly (2002) Thoughts about

education. New Horizons for Learning, Seattle.

http://education.jhu.edu/newhorizons/future/creating_t

he_future/crfut_csikszent.cfm

Henrick, Gavin; Cole, Jeanne and Cole, Jason (2011)

Moodle 2.0 for Business Beginner's Guide Packt

Publishing, Birmingham

Holtham, Clive and Courtney, Nigel (2006) High-

engagement learning for business education Higher

Education Academy Annual Conference, Nottingham,

3rd-5th July

Jawaheer, Gawesh; Kostkova, Patty; Sultany, Ajmal &

Bullimore, Anise (2011) Moodle Analytics Project:

Final Report City University, Learning Development

Centre, London

JISC Digital Media (2011) Use of VLEs with Digital

Media Accessed 19

th

November 2011: http://www.

jiscdigitalmedia.ac.uk/crossmedia/advice/introduction-

to-the-use-of-vles-with-digital-media

Kearsley, Greg & Shneiderman, Ben (1999) Engagement

Theory: A framework for technology-based teaching

and learning Version: 4/5/99 Accessed 9

th

December

2011: http://home.sprynet.com/~gkearsley/engage.htm

Krause, Kerri-Lee (2003) On Being Strategic About the

First Year, Griffith Institute for Higher Education,

Griffith University http://www3.griffith.edu.au/03/ltn

/docs/GIHE-First-Year-Experience.pdf

Krause, Kerri-Lee; McEwen, Celina and Blinco, Kerry

(2009) E-learning and the first year experience: A

framework for best practice EDUCAUSE Australasia

Conference, Perth, Western Australia, 3-6 May 2009

EVALUATINGENGAGEMENTTOADDRESSUNDERGRADUATEFIRSTYEARTRANSITION-ACaseStudy

227

Lane, L. M. (2009). Insidious Pedagogy: How course

management systems affect teaching. 14(10). First

Monday http://firstmonday.org/htbin/cgiwrap/bin/ojs/

index.php/fm/article/view/2530/2303

Macfadyen, Leah P. and Shane Dawson, (2010) “Mining

LMS Data to Develop an ‘Early Warning System’ for

Educators: A Proof of Concept,” Computers &

Education, vol. 54, no. 2 (2010), pp. 588–599.

Moodle.org (2011) About Moodle: Philosophy Accessed

19

th

November 2011: http://docs.moodle.org/21/en/

Philosophy

Naisbett, John (1999) High Tech, High Touch Broadway

Books, New York

Nicol, D. J. (2006). “Increasing success in first year

courses: assessment re-design, self-regulation and

learning technologies.” ASCILITE Conference,

Sydney, Dec 3-6, 2006

Rich M (2008) “Millennial Students and Technology

Choices for Information Searching”. The Electronic

Journal of Business Research Methods 6 (1), pp. 73 -

76, http://www.ejbrm.com

Romero, Cristóbal and Ventura, Sebastián (2010)

“Educational Data Mining: A Review of the State-of-

the-Art” IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and

Cybernetics—Part C: Applications and Reviews, Vol.

40, No. 6, pp601 – 618

Stringer, E. (1996) Action Research: A handbook for

Practitioners, Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Urwin, J. (2011) “Engagement with virtual learning

environments : a case study across faculties”, Blended

Learning in Practice, 2011: January , pp. 8-21.

CSEDU2012-4thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

228