MAKING USE OF MOBILE DEVICES IN E-COMMERCE

Overcoming Organizational Barriers through User Participation

Jan vom Brocke, Bettina Thurnher

Martin Hilti Chair of Information Systems and Business Process Management (IS&BPM)

University of Liechtenstein, Vaduz, Liechtenstein

Dietmar Winkler

Institute of Software Technology and Interactive Systems

Vienna University of Technology, Vienna, Austria

Keywords: Mobile Devices, Business Process Management, User Participation, Organisational Change.

Abstract: Mobile devices offer great potentials for the design of business processes. However, realizing these

potentials in practice is still problematic. While technologies are nowadays widely available, the problems

still lie in the management of organizational change. In this paper, we analyze the contribution of user

participation to the successful implementation of mobile business processes. We present the results of five

case studies conducted in the IT-Service sector. The work gives empirical evidence that user participation

(a) leads to reduced adoption and transition barriers and (b) improvements of business metrics.

1 INTRODUCTION

Mobile devices in information and communication

technology have raised great expectations during the

past years (Wang et al., 2005; Gumpp & Pousttchi,

2005). Following the discussion in academia and

industry, expectations go far beyond cost cutting. In

particular new business models (and hence new

ways of market reach) are inspired by mobile

devices. This is grounded by a number of recent

studies (cf. Kornak et al. 2004; Basole 2005; ; 2007).

In more detail, the potentials of mobile devices for

business process management include (a) the release

of workforce from desktop IT-Systems, (b)

replacement of paper-based processes, and (c) access

to corporate resources and automated online

information request (cf. Basole, 2005; Basole &

Rouse, 2007).

In practice, however, the successful implementation

of mobile business processes is still a serious

problem. Previous research has argued that

successful adoption and implementation of any

emerging devices, such as mobile devices, often

requires fundamental changes of a company’s

organisation (cf. Taylor & McAdam, 2004; Rouse,

2006). In fact, although mobile technology is widely

available nowadays, most projects fail in

establishing sustainable business processes that are

efficiently applied in the business processes of a

company. In our research, we focus on the role of

user participation when implementing mobile

business processes. According to research in

software- and usability engineering (e.g., Gibson

1977; Nielsen 1993; Barki & Hartwick, 1989,

Nielsen, 2003; Thurnher 2007, etc.) user

participation is expected to have a positive effect on

the efficient use of mobile devices in practice.

However, little empirical research is available that

looks at the effects of user participation in

introducing mobile devices. In particular, also the

costs of user participation have to be taken into

account and weighed against potential benefits.

From a normative perspective (cf. Hartman et al.,

2000; Ward & Peppard, 2002), different levels of

user participation have to be distinguished and

analysed regarding their value contribution in a

specific organisational context.

With this paper, we present the results of five case

studies in the IT service sector. In these studies, we

analysed the impact of user participation in different

projects on introducing mobile devices from 2005 to

2007. We anticipate that user participation within

168

vom Brocke J., Thurnher B. and Winkler D. (2008).

MAKING USE OF MOBILE DEVICES IN E-COMMERCE - Overcoming Organizational Barriers through User Participation.

In Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems - SAIC, pages 168-173

DOI: 10.5220/0001713501680173

Copyright

c

SciTePress

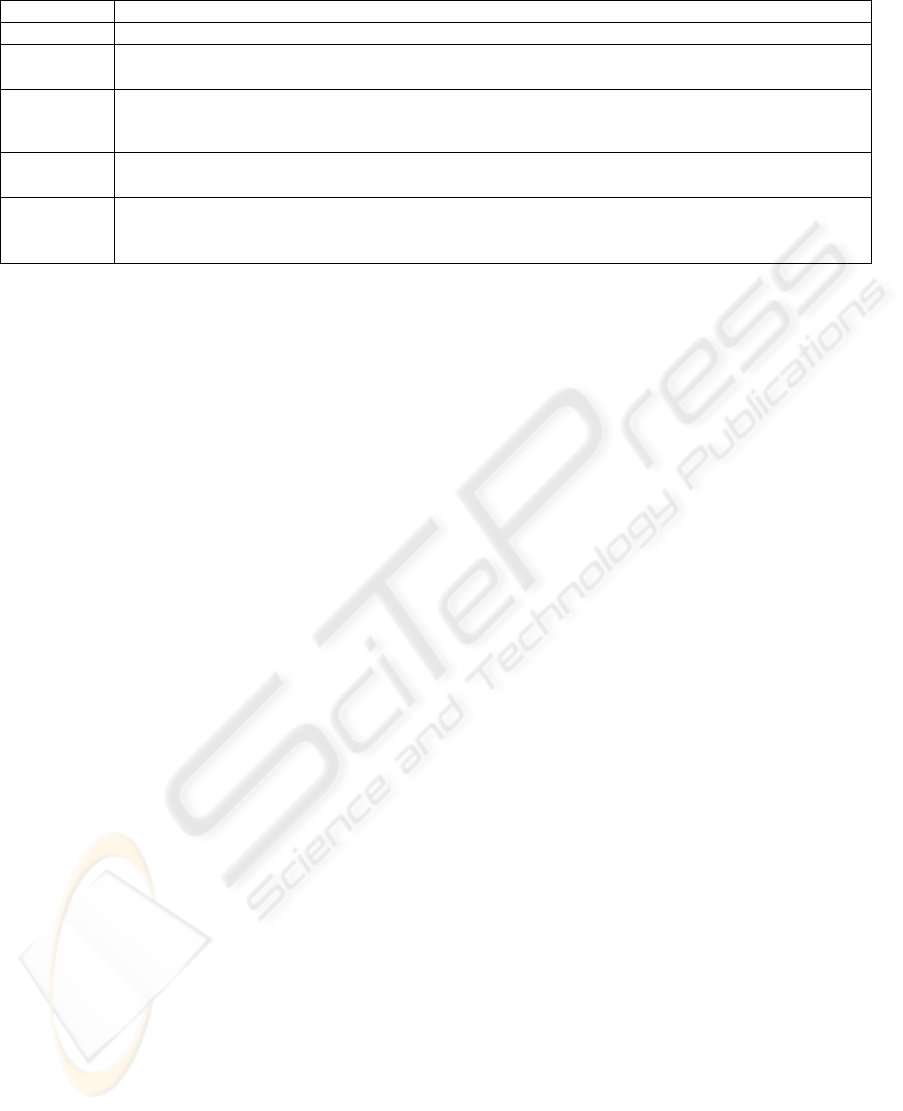

Table 1: KPI Definition and Measurement Approach.

KPI Definition

Time to Bill Duration [in days] from task completion to invoice submission.

SLA-Rate Service Success Rate [in %] is defined as the ratio of the duration from service request to fulfilment

of the request related to the agreed (in the customer contract) SLA.

Paper-

handling

time

Paper handling time [in days] is the duration from task completion until the submission of

performance data (working-, driving-time and number of used spare-parts) to head-office.

Payback

Period

The payback period [in years] is defined as the amortization time of mobile tool integration

(development and deployment costs) vs. reduced cost through mobile tool usage.

Tool

Acceptance

Attitudes towards usage and intentions to use the technology. This includes adoption and transition

barriers from the paper-based to the mobile tool supported process. Tools acceptance is based on

interviews and mapped to a nominal scale [1 .. low, 2 .. high end user acceptance]

the development process of a mobile tool leads to

faster adoption and acceptance of mobile devices.

We investigate different degrees of user

participation and report on their value contribution

by means of key performance indicators. The results

are presented as follows: In chapter 2 related work in

the field of mobile devices is reflected, particularly

distinguishing different levels of user participation.

On that basis the research design applied in our work

is introduced in chapter 3. The major findings of our

work are presented in chapter 4 and further

discussed in chapter 5. We conclude with a summary

and an outlook to future research given in chapter 6.

2 RELATED WORK

The Standish Group investigated a set of industry

projects (365 industrial responses involving more

then 8300 applications) and the main reasons for

project failure. The most important reasons for

project interruption were: (1) lack of management

support and (2) a lack of user involvement (Standish

Group, 2001). Obviously, strong user participation

during mobile tool development is necessary to fulfil

individual requirements of the target user group and

to address the need of the mobile devices within

business processes. The investigation of positive

impacts of user involvement and user participation

on system acceptance has been done extensively

within the ICT literature over the last 30 years of

ICT research, e.g., (Kaasinen, 2005; Nielsen, 2003;

Pedersen, 2002; Ives & Olson, 1986; Lucas 1974).

The terms user participation and user involvement

are often used inter-changeably in the Information

System literature. However, in other disciplines, the

concepts are accorded separately and have distinct

meanings (Barki & Hartwick, 1989). In order to

address this anomaly, Barki and Hartwick argue that

the term user participation be utilized to refer to

development-related activities and behaviours of

users and their representatives during the

development process, and that user involvement be

used to refer to the subjective psychological state

that reflects the level of importance and personal

relevance of the information system to users. These

researchers also argue that user participation is one

of the more important concepts, of user involvement.

User participation leads to increased system

acceptance by: (a) developing realistic expectations

about system capabilities (Gibson, 1977), (b)

providing an arena for bargaining and conflict

resolution about design issues, Leading to system

ownership by users (Robey & Farrow 1982) (c)

decreasing user resistance to change (Lucas, 1974)

(d) committing users to the system (Lucas, 1974).

Whereas the importance of user participation has

been pointed out in the literature in the last decades

(e.g., Lucas, 1974; Barki & Hartwick, 1989, Nielsen,

1999; Nielsen, 2003; Pousttchi & Thurnher 2007)

the integration of users within the software

development processes is still not considered

entirely throughout the industry and especially

within the IT-Service sector. The development of

tools is possible without user participation in the

design process – but deployment will be more

cumbersome due to adoption and acceptance barriers

amongst end users (Henneman, 1999). Whereas

linking usability considerations and user

participation to the impact on business metrics have

been investigated, e.g., by Nielsen, 2003; in depth

investigations targeted at mobile applications in the

IT-Service sector are missing so far. Nielsen (2003)

stated in his report that he estimates "… spending

about 10% of a project's budget on usability

activities doubles usability”.

The next section describes the research design,

the case study companies and the KPIs which have

been investigated.

MAKING USE OF MOBILE DEVICES IN E-COMMERCE - Overcoming Organizational Barriers through User

Participation

169

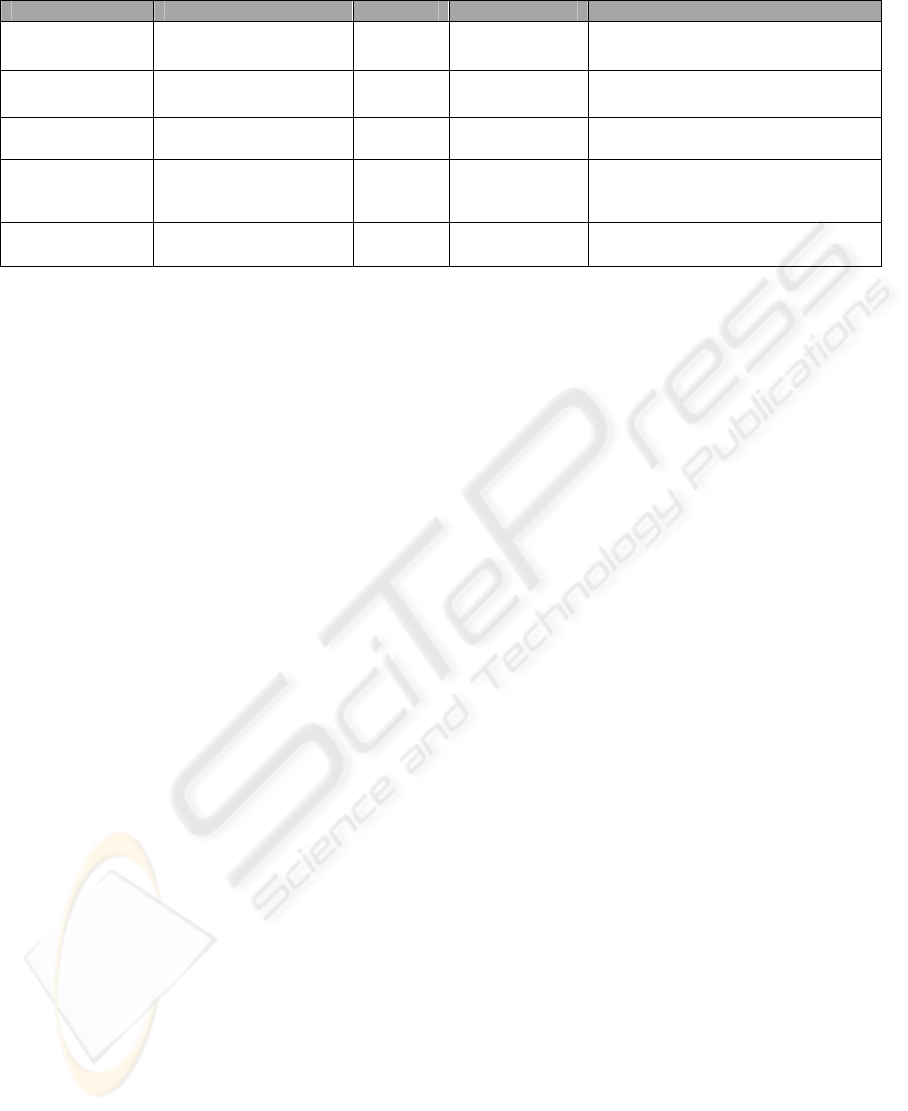

Table 2: Case Studies Description.

Company Provided Service # users Country Degree of User Participation

1)Telecommunica

tion Service

Technical customer

service

Large

(12,000)

Germany Little involvement; mainly in device

selection and testing

2)Municipal

Utility Company

Technical customer

service

Medium

(1,000)

Germany User participation in all phases

3)IT-Service

Provider

Technical customer

service

Small

(40)

Austria User participation in all phases

4)Toll Collection

& Railway

Maintenance

Technical customer

service

Mini

(7)

Austria Little user involvement; mainly in

the device selection phase

5)Machine

Construction

Technical customer

service

Large

(3,500)

Germany User participation in all phases

3 RESEARCH DESIGN

To investigate the impact of user participation and

KPIs within mobile business processes, we applied

case study research as it is appropriate for examining

practice-based problems, since it allows a researcher

to capture the knowledge of practitioners and

investigate business impact of methods or systems

(Anda, 2003; Benbasat et al., 1987; Creswell, 2002;

Eisenhardt, 1989). Where there is no ideal number

of cases which should be investigated in case study

research, Eisenhardt suggests conducting four to ten

case studies: “With fewer than four case studies it is

often difficult to generate theory with much

complexity and its empirical grounding is likely to

be unconvincing, unless the case has several mini-

cases”. (1989 p. 545) With more than ten cases it

becomes difficult to cope with the complexity and

saturation degree is already achieved (cf. Eisenhardt,

1989). Within this paper 5 case studies have been

undertaken in order to meet the suggestions of

Eisenhardt (1989) from a research perspective.

The studies were carried out in the IT-Service

sector. A basic IT-Service process starts with a

service request from the customer. Those requests

are classified according to predefined Service Level

Agreements (SLAs) with the customer. Dispatching

of the service requests is then arranged by the

dispatching/head-office department of the IT-

Service company. Then service technicians execute

service tasks (e.g., repair, installation and

maintenance of office machines). IT-Service

technicians are, e.g., engineers who work on the

customers’ side. Technicians are called either

periodically (e.g., continuous support for a set of

devices) or on-demand if unexpected events occur

e.g., machine break-down). After service task

execution the technicians have to capture and

transmit job related data (e.g., working- and driving

time, number of used spare parts). In the paper-

based process this has been done on a paper-form

which was transmitted to a desktop-system

(normally at the end of a working week by the

technician or head-office staff). When job data was

available head-office/finance department could start

with the billing process (prepare and send bill to the

customer). Through the application of mobile

devices an improvement of KPIs within the mobile

business process is expected. The KPIs under

investigation are depicted in Table 1. Despite the

numerous above mentioned value propositions and

the need of including the end user within software

development of mobile devices - within industry

projects user involvement is still not applied widely

(e.g., Nielsen 1993; Barki & Hartwick 1989;

Thurnher 2007) . In order to investigate and clarify

the value contribution of user participation within

the development process of mobile solutions we

formulated the following research questions (RQ).

RQ: What impact does user participation - in the

development phase of mobile tools - have on

business process key performance indicators after

deployment?

Expecting an improvement on the identified

KPIs, we focus on the degree of change (KPI

improvement). For instance, we expect a correlation

regarding the degree of user participation and

positive impact on KPIs.

For data gathering CEO, CTO, project managers

and end users of the mobile application were

questioned with semi-structured questionnaires in

face-to-face or via telephone interviews. Interviews

lasted 1 hour to 1.5 hours. The interviewees of the

case studies were selected based on their role in the

organization and their level of experience with

existing system and processes. Moreover,

interviewees were selected according to their

functions within the mobile application project (El-

Amrani et al., 2006).

Table 2 provides an overview of the case study

companies and shows the varying degrees of user

ICEIS 2008 - International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

170

participation within the mobile tool development

process. Moreover, it depicts that the companies are

comparable in terms of their provided service but

vary in their location (Austria/Germany) and the

number of IT-Service technicians (# users). All five

case studies were longitudinal studies in the IT-

Service sector within different industries and lasted

from 6 to 15 months. Interviews were transcripted

and fed back to the interviewees in order to reduce

possible errors and clarify misunderstandings. We

applied a semi-structured questionnaires (30

questions) in face-to-face or phone interviews. In

total we conducted 14 interviews; 6 persons had a

business - and 8 a technical background. 10

interviews were face-to face interviews and 4

telephone interviews.

In the following section major findings of our

work will be summarized.

4 FINDINGS

It was notable, that KPI improvements in percent

reached similar values in all case study companies

e.g., paper-handling time, time to bill, etc. before

and after mobile tool integration. Findings related to

our RQ are:

RQ: What impact does user participation - in the

development phase of mobile tools – have on

business process key performance indicators after

deployment?

We could observe that a higher degree of user

participation led to a faster / higher improvement of

KPIs and vice versa within companies with a lower

degree of user participation (e.g., only device

selection phase) a lower acceptance rate and a

smaller improvement of KPIs (e.g., longer payback

period) could be identified. The business process

improvement values are mainly given in percent as

absolute numbers referred to company sensitive

data.

In the following paragraphs further information

on the results will be given referring to each of the

key performance indicators listed in Table 1. Time

to Bill: As head-office staff has faster (directly after

job completion or at the end of a working day) job

data access the time to bill could be reduced

considerably by 75 to 50%, including single item

billing and total accounts. In the case study

companies (case 2, 3 and 5) with user participation

in all phases of mobile tool development the time to

bill increased by approx. 75% (e.g. from 21 working

days down to 5 working days). SLA-Rate: The

SLA-rate increased by 30 to 40%. This means that in

30 to 40% of all service cases the technician can

execute the job within the agreed SLA-time period

(e.g., within 24 hours after service request receipt).

This is due to improved information e.g., the service

order, problem description and spare-part

availability, as well as customer reachability. Again

in companies with a higher degree of user

participation the improvement was 40% whereas in

case 1 and 4 it only reached a 30% improvement.

Paper-handling time: The reduced paper-handling

time for the technicians was approx. 55-80% (from

30 minutes for job data capturing per job down to 5

minutes). This was due to the fact that double data

entry could be eliminated completely (entering the

paper-based form into a desktop-system). This

improvement was observed in all case study

companies whereas transition time (switching from

the paper-based to the mobile tool supported

process) was considerably longer in those cases with

lower degrees of user participation (2-3 months: case

2, 3 and 5; versus 6 months: case 1 and 4). Payback

Period: The payback period in the Telecom

Company was 2.5 years and in the Utility- and IT

Service Company was 1.5 years. In the Toll

Collection Company it took 1.6 years. And in the

Machine Construction Company only 1.3 years.

Shorter payback periods were observed in cases with

a high degree of user participation. During the

interviews we found this was due to smoother

adoption and transition phases of the mobile tool

supported workflow. The time for double process

execution, paper-based and mobile was reduced by

about 6 months in cases with user participation in all

development phases. Tool acceptance: Tool

acceptance varied in the case study companies

according to the degree of user participation versus

user involvement. We could observe that, the higher

the degree of user participation in the development

process of the mobile tool, the higher the acceptance

and intension of mobile tool usage after deployment.

In case study companies with little user involvement

tool acceptance and workflow change were

cumbersome. In Case Study Company 2, 3 and 5 we

observed a high user participation and high user

acceptance, while in Case Study Company 1 and 4

we observed little user involvement and low user

acceptance. Table 3 provides an overview of the

Case Study findings. Values are indicated in a

Likert-Scale (user participation, acceptance): 1 =

low; 5 = high and improvement values in per cent

(%). The Time to Bill is indicated in days,

comparing the former paper-based process duration

in days to the mobile tool supported duration.

MAKING USE OF MOBILE DEVICES IN E-COMMERCE - Overcoming Organizational Barriers through User

Participation

171

Table 3: Findings.

Company 1) Telco 2) Utility 3) IT-Service 4) Toll Coll. 5) Mach. Const.

User Participation 1 4 5 2 5

Time to Bill (days) 4 5 14 3 11

SLA-Rate (%) 25% 35% 45% 20% 40%

Paper-handling (%) 55% 70% 80% 60% 75%

Payback period (years) 2.5 1.5 1.5 1.6 1.3

Acceptance 2 4 5 1 4

From the results in Table 3 it can be concluded

that the higher the user participation in the

development was, the higher was tool acceptance.

Higher acceptance lead to faster transition times

(changing from the paper-based to the mobile tool

supported process) and that impacted KPIs

positively e.g., lead to higher improvements in the

Time to Bill.

Some ideas on the contribution these results

might add to research will be discussed in the

following chapter.

5 DISCUSSION

The findings presented in this paper provide

valuable insights in the field of mobility supported

business process and the role of user participation.

However, we are aware that the case study

approaches suffers from a number of shortcomings.

In order to overcome the limitations of case

study research a rich description of the context of the

study is provided, which can be used for

generalization to similar settings. For the research

purpose of this paper a single case study would not

have been appropriate due to several problems

linked to this research approach. Lee stats four major

problems of case study research (a) “making

controlled observations”, (b) “making controlled

deductions“, (c) “allowing for replicability” and (d)

“allowing for generalizability” (Eisenhardt, 1989).

The major strength of case study research is the

possibility of studying a phenomenon in depth in a

realistic (work) context. Weaknesses are related to a

lack of control, which leads to problems with

generalizing the results. Moreover, the data collected

may be interpreted in different ways, and the

intervention of the researcher may affect the

organization studied. Therefore, it may be difficult

to analyze causes of the observations made in the

study. Several practical challenges face the

researcher when undertaking a case study. For

example, it may be difficult for the organization to

find time to participate, and they may be unwilling

to give the researcher access to all their projects.

This may lead to a bias in the selection of projects

and cases studied. The organization may expect

quick and easily applicable results, which may run

counter to the goals and practice of the research

(Anda, 2003). In order to overcome the limitations

of case study research a rich description of the

context of the study is provided, which can be used

for generalization to similar settings.

6 CONCLUSIONS

With this paper we presented the results from five

industry case studies analysing the impact of user

participation on the success of introducing mobile

devices in business processes. In our examination

within the IT-Service sector 2 out of the 5

companies had a low degree of user participation. 3

companies had user participation within all phases of

mobile tool development and business process

redesign. The study gives evidence that user

participation within the development process of

mobile tools (a) leads to reduced adoption and

transition barriers as well as (b) improvements of

business metrics, especially the return on

investment.

These findings may provide a basis for further

research on the issue of managing organisational

change driven by innovative technologies. Working

with the results, however, we should consider that

the nature of case study research brings along some

limitations. In particular, we should be aware that

the results may be different when addressing other

context situations. Further research will therefore

focus on studies in diverse industry settings to foster

the generalizability of the results.

REFERENCES

Anda B., “Empirical studies of construction and

application of use case models,” PhD Thesis,

University of Oslo, 2003.

Barki H. and Hartwick J., “Rethinking the concept of user

involvement,” MIS Quarterly, Vol. 13, No. 1, pp. 53–

63, 1989.

ICEIS 2008 - International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

172

Basole R. and Rouse W. B., Towards the Mobile

Enterprise: Readiness and Transformation. IDEA

Group Publishing, 2007.

Basole R., “Mobilizing the enterprise: A conceptual model

of transformational value and enterprise readiness,” in

Proceedings of the 2005 American Society for

Engineering Management Conference, Virginia

Beach, VA, 2005.

Benbasat I., Goldstein D. K., and Mead M., “The case

research strategy in studies of information systems,”

MIS Quarterly, Vol. 11, No. 3, pp. 369–386, 1987.

Creswell J. W., Research Design: Qualitative,

Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 2nd ed.

Sage Publications, Inc., 7 2002.

Eisenhardt K. M., “Building theories from case study

research,” Academy of Management Review, Vol. 14,

No. 4, pp. 532–550, 1989.

El-Amrani R., Rowe F., and Geffroy-Maronnat B., “The

effects of enterprise resource planning implementation

strategy on cross-functionality”, Information Systems

Journal, Vol. 16, No. 1, pp. 79–104, January 2006.

Gibson H. L., “Determining user involvement,” Journal of

System Management, pp.

20–22, 1977.

Gumpp A. and Pousttchi K., “The Mobility-M-Framework

for application of mobile technology in business

processes,” in GI Jahrestagung (2), ser. LNI, Cremers

A. B., Manthey R., Martini P., and Steinhage V., Eds.,

Vol. 68. GI, 2005, pp. 523–527.

Hartman A., Sifonis J. G., and Kador J., Net Ready:

Strategies for Success in the

E-Conomy. McGraw-Hill, 2000.

Henneman R. L., “Design for usability: Process, skills,

and tools,” Journal of Information Knowledge System

Management, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 133–144, 1999.

Hofstede G., Cultures and Organizations - Software of the

Mind. Intercultural Cooperation and Its Importance

for Survival: Software for the Mind. Mcgraw-

HillProfessional, 1991.

ITIL , “Einführung in ITIL,” Tech. Rep., 2005.

Ives B. and Olson M. H., “User Involvement and MIS

Success: A review of Research”, Management

Science, Vol. 30, No. 5, pp. 586–603, 1984.

Kaasinen E., User acceptance of mobile services - value,

ease of use, trust and ease of adoption. VTT

Publications, 2005.

Keen P. G. W., “Information system and organizational

change,” Communications of the ACM, Vol. 24, No. 1,

pp. 24–33, 1981.

Kornak A., Teutloff J., and Welin-Berger M., Enterprise

Guide to Gaining Business Value from Mobile

Technologies. Wiley, 2004.

Lucas H. C., “Systems quality, user reaction and the use of

information systems,” Management Informatics, Vol.

3, No. 4, pp. 207–212, 1974.

Nielsen J., “Usability return on investment,” Nielsen

Norman Group Report,

http://www.nngroup.com/reports/roi/, Report, 2003.

Nielsen J., Usability Engineering. New York: AP

Professional, 1993.

Pedersen P., Methlie L., and Thorbjrnsen H.,

“Understanding mobile commerce enduser adoption: a

triangulation perspective and suggestions for an

exploratory service evaluation framework,” in HICSS-

35, Hawaii, US, 2002, pp. 1–8.

Pousttchi K. and Thurnher B., “Adoption and impact of

mobile-integrated business processes - comparison of

existing frameworks and analysis of their

generalization potential,” in Proceedings of

Internationale Tagung Wirtschaftsinformatik,

Oberweis A., Weinhardt C., Gimpel H., Koschmider

A., Pankratius V., and Schnizler B., Eds.

eOrganisation: Service-, Prozess-, Market-

Engineering. 8. Internationale Tagung

Wirtschaftsinformatik. Bd. 1, Karlsruhe, 2007, pp.

273–290.

Robey D. and Farrow D., “User involvement in

information system development: A conflict model

and empirical test,” Management Science, Vol. 1, pp.

73–85, 1982.

Rouse W. B., Enterprise Transformation: Understanding

and Enabling Fundamental Change, Wiley Series in

Systems Engineering and Management ed. Wiley-

Interscience, 2006.

The Standish Group, “Chaos report,” online, 2001.

Wang Y., van de Kar E., Meijer G., and Hunteler M.,

“Improving business processes with mobile workforce

solutions,” ICMB, Vol. 1, pp. 94–102, 2005.

Ward J. and Peppard J., Strategic Planning for

Information Systems. John Wiley & Sons, 2002.

MAKING USE OF MOBILE DEVICES IN E-COMMERCE - Overcoming Organizational Barriers through User

Participation

173