EFFECTIVENESS

OF AVATARS FOR SUBJECTIVE ANNOTATION

Fuyuko Ito

Graduate School of Engineering, Doshisha University, Japan

Yasunari Sasaki, Tomoyuki Hiroyasu, Mitsunori Miki

Department of Engineering, Doshisha University, Japan

Keywords:

Avatar, subjectivity, feeling, annotation, collaborative tagging, folksonomy, consistency, expressiveness, con-

tents management.

Abstract:

Consumer Generated Media (CGM) is growing rapidly and the amount of content is increasing. However, it is

often difficult for users to extract important contents and the existence of contents recording their experiences

can easily be forgotten. As there are no methods or systems to indicate the subjective value of the contents or

ways to reuse them, subjective annotation appending subjectivity, such as feelings and intentions, to contents

is needed. Representation of subjectivity depends on not only verbal expression, but also nonverbal expres-

sion. Linguistically expressed annotation, typified by collaborative tagging in social bookmarking systems,

has come into widespread use, but there is no system of nonverbally expressed annotation on the web. We

proposed the use of controllable avatars as a means of nonverbal expression of subjectivity, and confirmed the

consistency of feelings elicited by avatars over time for an individual and in a group. In addition, we compared

the expressiveness and ease of subjective annotation between collaborative tagging and controllable avatars.

The result indicated that the feelings evoked by avatars are consistent in both cases, and using controllable

avatars is easier than collaborative tagging for representing feelings elicited by contents that do not express

meaning, such as photos.

1 INTRODUCTION

There has been an increase in development and uti-

lization of social software that shares private informa-

tion such as photos and diaries, among a community

or the general public. As each user publishes their

own contents on the web, the amount of web content

has increased rapidly. Therefore, it has become dif-

ficult to extract necessary information and much of

the information that is available is left unused. The

current mainstream method of information retrieval

is to use keywords for the contents, but searching by

subjective information, such as feelings or intention,

is expected to allow users to find forgotten informa-

tion. Therefore, we propose gsubjective annotationh

in which users annotate contents with subjective in-

formation, and construct a content management sys-

tem to store and browse the contents based on the sub-

jective annotation.

Preliminary experimental results on expressive-

ness and ease of subjective annotation by collabora-

tive tags used for classification in social bookmarking

systems and blogs suggested that it may be difficult

to express subjectivity by verbal expression, such as

tags. In this paper, we propose the usage of avatars

as a means of nonverbal expression of subjectivity,

and report verification of its validity by experiments

on the consistency of feelings elicited by avatars over

time for an individual or a group of people. We also

compare the expressiveness and ease of subjectivity

between avatars and tags.

2 WEB CONTENT

MANAGEMENT AND

ANNOTATION

Consumer Generated Media (CGM), such as weblogs

(commonly referred to as ”blogs”) and photos, which

are published by users have increased rapidly because

the contents previously stored on local terminals are

now available on the web. To manage this large

amount of web content, social bookmarking services

74

Ito F., Sasaki Y., Hiroyasu T. and Miki M. (2008).

EFFECTIVENESS OF AVATARS FOR SUBJECTIVE ANNOTATION.

In Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies, pages 74-81

DOI: 10.5220/0001524700740081

Copyright

c

SciTePress

have appeared.

Social bookmarking services manage their con-

tents from the bottom-up by sharing annotations, such

as tags or keywords, which are added to the contents

by users (Mathes, 2004). This enables the discovery

of related contents through tags, and users can reach

information that would otherwise be difficult to find.

However, increasing the number of tags makes it

difficult for users to keep track of their tags. So-

cial software stores the contents that are important to

users, but there are few chances to browse these con-

tents again. Even if tags are added to ease content

searching, users will not search the contents without

a clear purpose, and many of the contents that may

be important for users may be left unused in social

software.

3 SUBJECTIVE ANNOTATION

3.1 What is Subjective Annotation?

We propose ”subjective annotation,” which involves

adding subjective information, such as feeling or in-

tention, to the contents. Currently, it is common to an-

notate web contents using a number of tags. Most of

these tags explain the contents objectively, and only

a few tags indicate subjective information. The so-

cial bookmarking service del.icio.us

1

has some tags

that indicate subjectivity, such as ”to be read,” which

make it easier for users to determine how to use the

contents. At the photo sharing service Flickr

2

, some

photos are tagged ”cute” or ”cool”, and users can

search and classify photos according to their own im-

pressions and values (Golder and Huberman, 2006).

Therefore, subjective annotation can assist users to

make efficient use of web contents.

3.2 Contents Management System

based on Subjectivity

Here, we constructed a content management system

based on subjective annotation that helps users to dis-

cover knowledge from their past experiences. The

proposed system recreates their past feelings and ex-

citement by using subjective annotation over a wide

variety of contents and reminds users of their behav-

iors. The system targets the web contents of social

software, such as photo sharing, social bookmarking,

and schedule sharing services that are browsed only

1

http://del.icio.us/

2

http://flickr.com/

when users need them. To utilize wasteful accumu-

lated contents, the system accumulates the contents

with subjective annotation in social software and pro-

vides a content browsing environment based on sub-

jectivity.

3.3 Collaborative Tags for Subjectivity

Expression

The expression of subjectivity must be considered to

implement subjective annotation. Most annotations

describe the contents in some way, and the expres-

siveness of the current annotation methods regarding

subjectivity and user stress must be assessed. First,

we adopted collaborative tagging, which is commonly

used as a means of annotation of web contents, as

an expression of subjectivity and performed an ex-

ploratory experiment on the expressiveness of subjec-

tivity and user stress.

In the experiment, 20 participants tagged 10 pho-

tos with subjective information, such as feelings and

impressions, and answered a questionnaire survey. A

wide variety of subjectivity, such as intention, feel-

ings, and imagery unclear, were used as tags. How-

ever, participants reported feelings of stress regarding

the difficulty of verbalizing subjectivity.

The questionnaire survey indicated that it is dif-

ficult to verbalize subjectivity with tags. There-

fore, subjectivity must be expressed by a nonverbal

method. We adopted an avatar for this purpose, as it

seemed suitable to express subjectivity such as feel-

ings. It is easy to deal with avatars on computers and

users often identify themselves with avatars. There-

fore, avatars allow users to express their feelings nat-

urally and they are able to express their feelings with

gestures. In addition, recognition of avatars is consis-

tent from person to person, even with different nation-

alities (Ekman and Friesen, 1971).

4 AVATARS AS NONVERBAL

EXPRESSION OF

SUBJECTIVITY

4.1 Controllable Avatars for Subjective

Annotation

We adopted a controllable avatar to express a wide va-

riety of feelings. The avatar has a variety of patterns

of facial expressions, and arm and leg positions. Fig-

ure 1 shows examples of avatars and Figure 2 shows

all parts of the avatars. Users combine these face,

arm, and leg parts to express their feelings.

EFFECTIVENESS OF AVATARS FOR SUBJECTIVE ANNOTATION

75

Figure 1: The examples of the avatar.

Faces

(1) (2) (3) (4)

(5) (6)

(7) (8) (9) (10)

Arms

(1) (2) (3) (4)

Legs

(1) (2)

Figure 2: The avatar consists of faces, arms and legs.

The avatar used for nonverbal expression of sub-

jectivity is shown in Figure 1 as a cartoon charac-

ter. There are three reasons why we use this type of

avatar. Firstly, We think Japanese show a preference

for animated illustrations rather than realistic figures

like Second Life

3

’s avatars. Secondly, Takahashi et

al. (Takahashi et al., 2005) used two different car-

toon imaginary characters which are neither human

nor animals. On the other hand, a human charac-

ter is adopted as an avatar in this research, and en-

ables the users’ identities to be expressed by chang-

ing hairstyles or hair colors. This is so that the avatar

of each user can be recognized by their looks. How-

ever, our avatars don’t emphasize the users’ identi-

ties such as changing clothes and accessories, because

the main focus of our avatars is feeling expression by

faces and body movement. This is the last reason.

Thus, our avatars are different from the avatars of Ya-

hoo!Avatars

4

. Also we will not refer to hairstyles of

avatars in this paper.

4.2 Validity of Avatars for Nonverbal

Expression of Subjectivity

The subjective information that is added by subjec-

tive annotation will be used as queries to search and

classify contents. Furthermore, information filtering

based on subjectivity of other users is possible by

sharing subjective annotation among communities or

the general public, similar to collaborative tags. To

achieve this, the following factors must be assessed

by experiments.

• Consistency of feelings elicited by avatars for an

individual over time.

• Consistency of feelings elicited by avatars in a

group of people.

• Comparison of feeling expressiveness between

avatars and collaborative tags.

3

http://secondlife.com/

4

http://avatars.yahoo.com/

It is necessary to assess whether subjectivity, par-

ticularly feelings, elicited by avatars changes signif-

icantly over time for an individual, and also within

groups of people. Moreover, the comparison of feel-

ing expressiveness, satisfaction level of their own ex-

pression, and adaptability on of contents must be con-

ducted between avatars and collaborative tags.

5 CONSISTENCY OF FEELINGS

ELICITED BY AVATARS FOR

AN INDIVIDUAL OVER TIME

5.1 Experimental Overview

To facilitate use of avatars for personal information

retrieval and experience browsing, the consistency of

feelings elicited by the avatars over time was assessed

based on a semantic differential method. Moreover,

features of feelings over time for each avatar pattern

are also discussed.

Avatars. In this experiment, the variety of avatar

faces was limited to face parts from (1) to (6) shown

in Figure 2 that were frequently used in a prelimi-

nary experiment of feeling expression. Leg parts were

fixed to leg parts(1), because participants reported a

greater effect of the arms than the legs in the prelimi-

nary experiment. A total of 24 avatars (6 face parts ×

4 arm parts) were presented to the participants.

Participants. Two men and 2 women ranging in age

from 23 to 25 years participated in this experiment.

All participants were Japanese university students.

Measurement. In this experiment, participants rated

the feelings elicited by the avatars using a seman-

tic differential method based on the two-dimensional

model of emotion proposed by Lang (Lang, 1995).

Participants rated the arousal and the valence from 0

(lowest) to 100 (highest) for each of avatar pattern on

six continuous-valued scales. A total of 144 stimuli

(24 avatar patterns × 6 scales) were presented to the

participants.

Each scale was anchored with a pair of antony-

mous words in Japanese, which were determined hi-

erarchically. In the preliminary experiment, partici-

pants labeled each avatar pattern with various words

indicating feelings. Then, pairs of antonymous words

were made from frequently used words. The pairs

of words were reduced to the six pairs shown be-

low, which are frequently used in the areas of social

psychology and personality psychology, according to

the survey results of scale construction of pairs of

Japanese antonymous words in a semantic differential

WEBIST 2008 - International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

76

Figure 3: The experimental setup.

method reported by Inoue et al (Inoue and Kobayashi,

1985). The approximate translations to English are as

follows:

• Arousal

– scale 1 (intension) : intense - calm

– scale 2 (activeness) : active - passive

– scale 3 (strength) : strong - weak

• Valence

– scale 4 (joy) : joyful - sad

– scale 5 (amusement) : amusing - boring

– scale 6 (favor) : likable - dislikable

Process.

1. After receiving instructions, participants were

trained to evaluate feelings.

2. Avatars were presented on the computer screen

(see Figure 3). Moreover, the order of presenta-

tion of faces and arms is counterbalanced across

the trials.

3. Participants evaluated the feelings elicited by the

avatars on each scale. The order of scales was

randomized for each avatar. The time limit was

set to 40 s for each avatar pattern to induce an

intuitive response.

4. Twenty-four avatars were presented by iterating

steps 2 and 3. After evaluation, participants an-

swered the questionnaire.

5. From step 1 to 4 was defined as a trial. Six trials

were conducted at the following intervals: 1 h, 2

h, 1 day, 2 days, 4 days.

6. More than 2 weeks after step 5, participants were

presented with all avatars and means of their eval-

uated values for each scale. Participants indicated

their satisfaction level from 0 to 100.

5.2 Results and Discussion

We evaluated the standard deviation of the spread

in the evaluated values for feelings elicited by each

avatar pattern and defined that as the statistical value.

Feelings elicited by the avatar pattern that are more

than mean+1SD were particularly inconsistent. Con-

versely, feelings elicited by the avatar pattern that

Table 1: Amount of avatar patterns outside the mean±1SD

range.

Participant >+1SD <-1SD

Arousal Valence Arousal Valence

A 17 2 5 14

B 9 9 7 12

C 17 9 2 14

D 14 8 5 15

are less than mean−1SD were particularly consistent.

There were average of 21 avatar patterns that are more

than mean+1SD for participants. These patterns cor-

responded to only about 14% of the entire 144 stimuli

(24 avatar patterns × 6 scales). Therefore, feelings

elicited by avatars are generally consistent over time

for individuals. Moreover, Table 1 shows the amounts

of avatar patterns outside the mean±1SD range of

arousal and valence.

There were more avatar patterns that are more than

mean+1SD in scales of arousal (see Table 1). On the

other hand, there were more patterns that are less than

mean−1SD in scales of valence (see Table 1). There-

fore, valence elicited by avatars is more consistent

over time than arousal for an individual.

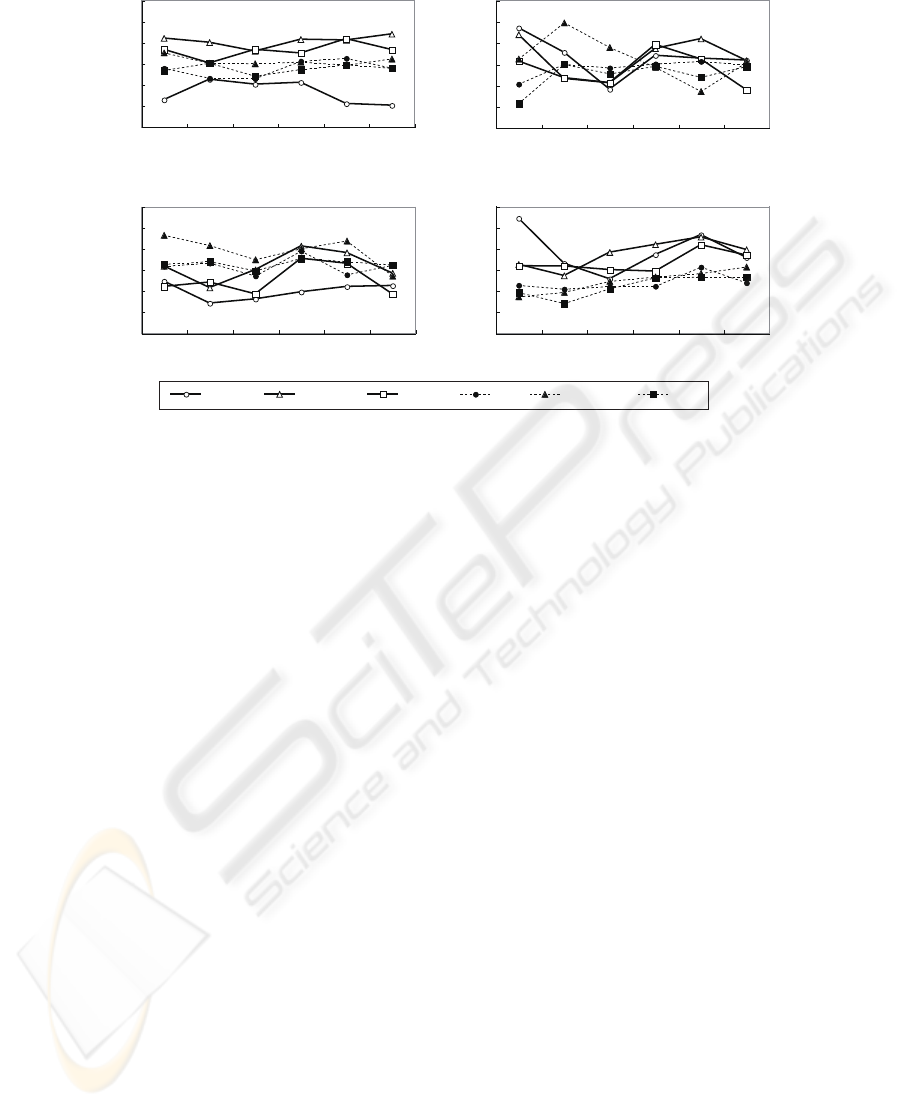

Figure 4 shows the transition of the total evaluated

values for each participant throughout all trials. The

figures show that the total evaluated values of arousal

changed more drastically than valence throughout all

trials.

The evaluated values of valence, such as ”joy” and

”favor”, were simply increased and evaluated more

positively due to the mere exposure effect(Zajonc,

1968). However, the evaluated values of arousal de-

creased from the first to the third trial, which may

have been due to loss of novelty with three trials in

one day.

Furthermore, two weeks after the experiment, par-

ticipants reported the satisfaction level of each avatar

pattern and its average evaluation value throughout

all trials. The satisfaction level was defined as the

statistical value, and we inspected the frequencies of

face parts and arm parts in avatar patterns that are less

than mean−1SD. Face parts (2) (see Figure 2) ap-

peared frequently in avatar patterns that are less than

mean−1SD. The satisfaction level of face parts (2)

tended to be low, as it was difficult for participants to

determine whether the feeling was positive or nega-

tive from the surprised face and the evaluation of va-

lence was inconsistent. On the other hand, arm parts

(3) (see Figure 2) appeared frequently in avatar pat-

terns that are more than mean+1SD. The satisfaction

level of arm parts (3) tended to be high, as waving

arms emphasized the feeling expressed by avatars and

made a deep impression on the participants.

Taken together, these observations indicated that

EFFECTIVENESS OF AVATARS FOR SUBJECTIVE ANNOTATION

77

-15

-10

-5

0

5

10

15

1 2 3 4 5 6

trials

(a) Participant A

standardized evaluated value

-15

-10

-5

0

5

10

15

1 2 3 4 5 6

(b) Participant B

trials

standardized evaluated value

-15

-10

-5

0

5

10

15

1 2 3 4 5 6

(c) Participant C

trials

standardized evaluated value

-15

-10

-5

0

5

10

15

1 2 3 4 5 6

(d) Participant D

trials

standardized evaluated value

Intention Activeness Strength Joy Amusement Favor

Figure 4: Total evaluated value of each scales.

feelings elicited by avatars are consistent over time

for an individual.

6 CONSISTENCY OF FEELINGS

ELICITED BY AVATARS IN A

GROUP OF PEOPLE

6.1 Experimental Overview

We examined use of an avatar as a query for informa-

tion filtering in a group of people as with collaborative

tags. The consistency of feeling elicited by avatars in

a group of people was assessed based on a semantic

differential method in the same way as in the exper-

iment described in Chapter 5. Features of feelings

generated by participants are also discussed.

Design. A 6(faces) × 4(arms) within-subject experi-

ment was performed. The avatar parts used in this ex-

periment were the same as those described in Chapter

5. Overall, 24 avatars were presented to the partici-

pants.

Participants. Twenty men and 4 women ranging in

age from 21 to 27 years participated in this experi-

ment. All participants were Japanese university stu-

dents.

Measurement. This experiment was performed

based on the semantic differential method in the same

way as the experiment described in Chapter 5. The

pairs of antonymous words anchored on the six scales

were also the same as those in Section 5.1. A total

of 144 stimuli (24 avatar patterns × 6 scales) were

presented to the participants.

Process.

1. After receiving instructions, participants were

trained to evaluate feelings.

2. Avatars were presented on the computer screen.

Moreover, the order of presentation of faces and

arms is counterbalanced across the participants.

3. Participants evaluated the feelings elicited by the

avatars on each scale. The order of scales was

randomized for each avatar. The time limit was

set to 40 s.

4. Twenty-four avatars were presented by iterating

steps 2 and 3. After evaluation, participants an-

swered the questionnaire.

6.2 Results and Discussion

We evaluated the semi inter-quartile range of stan-

dardized evaluated values for each scale, for each

avatar to inspect the spread of feelings, and defined

that as the statistical value. The feelings elicited by

avatar patterns that are more than mean+2SD were

particularly inconsistent. Conversely, the avatar pat-

terns that are less than mean−2SD were very consis-

tent. There were 7 avatar patterns that are more than

mean+2SD. These patterns accounted for only about

7% of the total of 144 stimuli (24 avatar patterns ×

6 scales). Therefore, feelings elicited by avatars were

consistent in a group of people as a whole.

WEBIST 2008 - International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

78

Table 2: Amount of avatar patterns outside the mean±2SD

range.

>+2SD <-2SD

Arousal Valence Arousal Valence

7 0 0 2

Meanwhile, the amounts of patterns outside the

mean±2SD range of the semi inter-quartile range

were summarized for arousal and valence (see Ta-

ble 2). There were more patterns that are more than

mean+2SD in scales of arousal. On the other hand,

there were more patterns that are less than mean−2SD

in scales of valence. There are two reasons why va-

lence elicited by avatars was more consistent than

arousal. First, scales of valence are nominal, and

users could recognize feelings from facial expres-

sions. The other reason is that arousal is an interval

scale and its degree is inconsistent even within an in-

dividual.

Avatar patterns and scales that are more than

mean+2SD are discussed in detail. Valence showed

a much wider spread than arousal when the avatar

consisted of face parts (3), because it is difficult to

determine between pleasure and displeasure from the

excited face. Moreover, the evaluation of scale for

joy was particularly consistent as compared to other

scales.

Two-way ANOVA of the 6(faces) × 4(arms) pat-

terns was conducted for each of the following scales

to inspect the features and effects of feelings elicited

by avatars.

Intension. The interaction between faces and arms

was marginally significant (F(15, 345) = 1.58, p <

.1). Fisherfs least significant difference (LSD) post

hoc test was used to test the differences in pairwise

comparisons. The face parts (2), (3), and (5) were

different from (1), (4), and (6) (p < .05). Therefore,

these face parts increased arousal. Meanwhile, arm

movement also affected intention, and arm part (3)

was significantly different from arm parts (1), (2), and

(4) (p < .05).

Activeness. The main effects of faces and arms were

significant (F(5, 115) = 38.42, p < .01; F(3, 69) =

23.53, p < .01, respectively). However, there was

no significant interaction between faces and arms

(F(15, 345) = 1.13,n.s.).

Strength. The interaction between faces and arms

was marginally significant (F(15, 345) = 1.74, p <

.1). On LSD post hoc test, face part (4) was signif-

icantly different from the other face parts (p < .05).

Joy. The interaction between faces and arms was sig-

nificant (F(15, 345) = 2.18, p < .05). On LSD post

hoc test, the face parts (1) and (3) were significantly

different from the other face parts (p < .05).

Amusement. The interaction between faces and arms

was significant (F(15, 345) = 2.31, p < .01). On LSD

post hoc test, face parts (1) and (3) were significantly

different from the other face parts (p < .05).

Favor. The interaction between faces and arms was

significant (F(15, 345) = 2.25, p < .01). On LSD

post hoc test, arm parts (3) was significantly differ-

ent from arm parts (1) and (2) when face parts was (3)

or (6)(p < .05).

Taken together, these observations indicated that

feelings elicited by avatars are consistent in a group

of people and facial expressions affect valence, while

arm movements affect arousal, although face parts

(2), (3), and (5), which expressed surprise, excite-

ment, and anger, respectively, increased arousal.

7 COMPARISON OF FEELING

EXPRESSIVENESS BETWEEN

AVATARS AND TAGS

7.1 Experimental Overview

The expressiveness, gap in expression according to

the contents, ease, and satisfaction of expression were

compared between avatars and collaborative tags rep-

resenting nonverbal and verbal expression, respec-

tively. In this experiment, participants expressed their

feelings elicited by contents, which consisted of arti-

cles as verbal contents and photos as nonverbal con-

tents, using avatars or tags.

This experiment was performed using all of the

avatar parts shown in Figure 2. The participants ex-

pressed their feelings elicited by contents with a com-

bination of these avatar parts. The format of collabo-

rative tags was open-ended, and participants were per-

mitted to use multiple tags for a single content. Fur-

thermore, participants were allowed to skip the ex-

pression if they felt difficulty in expressing their feel-

ings.

The contents were articles and photos on the

web. Practically, top 10 bookmarked articles in Ya-

hoo!Japan News

5

as of September 5th, 2007 and top

10 bookmarked photos in Zorg

6

( photo sharing ser-

vice) as of August 1st, 2007 were chosen for this ex-

periment.

5

http://headlines.yahoo.co.jp/

6

http://www.zorg.com/

EFFECTIVENESS OF AVATARS FOR SUBJECTIVE ANNOTATION

79

(a) Participants express

their feelings elicited from

the article with an avatar.

(b) Participants express

their feelings elicited

from the photo with tags.

Figure 5: The experimental setups.

Participants. Twenty men and 4 women ranging in

age from 21 to 27 years participated in this experi-

ment. All participants were Japanese university stu-

dents.

Process.

1. After an instruction, the participants are trained to

express their feelings using avatars or tags to the

sample article and the sample photo. Moreover,

the order of using avatars and tags is counterbal-

anced across the participants.

2. Ten articles and 10 photos were presented on the

computer screen (see Figure 5). The participants

expressed their feelings regarding the contents us-

ing avatars or tags, respectively. The presentation

order of articles and photos was counterbalanced

across participants.

3. The participants expressed their feelings regard-

ing the same contents in the same way as in steps

1 and 2 using tags or avatars that have not been

used before.

4. After evaluation, participants answered the ques-

tionnaire about their satisfaction.

7.2 Results and Discussion

Figure 6 shows the results of 3 questionnaires on the

satisfaction of feelings expression by avatars and tags.

The participants responded regarding which of the

two expression methods they preferred. Each ques-

tionnaire was about the entire contents, articles, and

photos. In all questionnaires, none of the participants

indicated a preference for tags over avatars.

With regard to all contents, more than 70% of

the participants indicated a preference for expressing

their feelings using avatars (see Figure 6(a)). This

may have been because an avatar can express feel-

ings that are difficult to verbalize, and an avatar can

describe the degree or strength of a feeling.

On the other hand, 58% and 67% of participants

indicated a preference for avatars for expression of

feelings regarding articles (see Figure 6(b)) and for

photos (see Figure 6(c)), respectively. Moreover, 38%

and 8% of participants indicated that tags are better

than avatars for articles and for photos, respectively.

Based on the opinions of the participants, it is not

difficult to express feelings with tags in the case of

articles, as articles themselves are in verbal format.

However, the meanings of photos cannot be defined

clearly, and it is difficult to verbalize feelings elicited

by photos.

In this experiment, participants were allowed to

skip expression of feelings if they decided that expres-

sion with the suggested method was impossible. The

number of skips was 21 times using avatars and 42

times with tags. Thus, it seemed to be easier for users

to use avatars than tags.

8 RELATED WORKS

There has been a lot of studies using avatars: cre-

ation of co-presence in online communication (Ishii

29%

38%

8%

25%

17%

13%

41%

29%

38%

4%

37%

21%

Avatars expressed feelings very well.

Avatars expressed feelings better than tags.

It is hard to choose between avatars and tags.

Tags expressed feelings better than avatars.

Tags expressed feelings very well.

(a) Both of

articles and photos.

(b) Articles. (c) Photos.

Which expressed your feelings about the contents better, avatars or tags?

Figure 6: Results of questionnaires about satisfaction level of feeling expression.

WEBIST 2008 - International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

80

and Watanabe, 2003), interpretation of avatar’s facial

expressions (Koda and Ishida, 2006), description lan-

guage for avatar’s multimodal behavior (Prendinger,

2004) and so on. However, there has been a few cases

using avatars for feeling extraction. In this section, we

will mention representative studies that use avatars for

feeling extraction.

Takahashi et al. (Takahashi et al., 2005) con-

structed TelMeA, an asynchronous communication

support system, which presents the relations among

participants and the relations between contents and

conversations by the behavior of static avatars. The

purpose of TelMeA is similar to ours, because

TelMeA was designed to ease interpretation of feel-

ings difficult to express verbally, by combining the

the contexts and the behaviors of avatars. However,

we defined feeling expressions by avatars as a part of

subjective annotation, and planned to use them like

collaborative tags for information retrieval and classi-

fication in contents sharing. For this reason, we ver-

ified the consistency of feelings elicited by avatars.

Moreover, our avatars could express feeling towards

the contents not only with clear context, but also with

unclear context such as photos.

Another case, PrEmo (Desmet, 2003), is a tool

to assess emotional responses toward consumer prod-

ucts. In PrEmo, avatars have 14 behaviors, which

consisting of 7 positive and 7 negative behaviors.

Users rate each avatar based on the feelings elicited

by the products. This tool enables product impres-

sion analysis based on user’s feelings. The purpose of

PrEmo is similar to ours because it was designed to

analyze feelings elicited by targets. However, the re-

sults of feeling analysis for each product using PrEmo

were mapped all together in the emotion space struc-

tured by 14 avatar behaviors. Therefore, users cannot

easily share their feelings elicited by each product.

Moreover, in PrEmo, the rating for each avatar only

indicates that the feeling that each avatar represents is

present in the user’s feeling elicited by products. On

the other hand, our avatar can express not only the

presence of feelings, but also degrees of them.

9 CONCLUSIONS

We proposed subjective annotation where users add

subjective information, such as feelings and intention,

to the contents. As it is particularly difficult to verbal-

ize a feeling, we adopted avatars to express feelings.

To use an avatar as the interface of subjective anno-

tation, the consistency of feelings elicited by avatars

over time for an individual, and also the consistency

in a group of people were assessed. The results indi-

cated consistency for both cases, although the varia-

tion of arousal was wider than that of valence.

In addition, a comparison was conducted regard-

ing feeling expressiveness and satisfaction level be-

tween avatars and collaborative tags. The results in-

dicated that avatars are more suitable than tags for ex-

pression of feelings, particularly in cases with con-

tents that include no context and no message, such

as photos. Overall, avatars could be used for expres-

sion of subjective annotation. In future studies, we

will improve the control interfaces of avatars to make

them more intuitive and continue to verify the practi-

cal usefulness of subjective annotation with avatars.

REFERENCES

Desmet, P. M. (2003). Measuring emotions. In Funology:

from usability to enjoyment, pages 111–123. Kluwer

Academic Publishers.

Ekman, P. and Friesen, W. V. (1971). Constants across cul-

tures in the face and emotion. Personality and Social

Psychology, 17(2):124–129.

Golder, S. A. and Huberman, B. A. (2006). Usage patterns

of collaborative tagging systems. Journal of Informa-

tion Science, 32(2):198–208.

Inoue, M. and Kobayashi, T. (1985). The research domain

and scale construction of adjective-pairs in a semantic

differential method in japan. The Japanese Journal of

Educational Psychology, 33(3):253–260.

Ishii, Y. and Watanabe, T. (2003). An embodied video com-

munication system in which self-referentiable avatar

is superimposed for virtual face-to-face scene. Jour-

nal of the Visualization Society of Japan, 23(1):357–

360.

Koda, T. and Ishida, T. (2006). Cross-cultural comparison

of interpretation of avatars’ facial expressions. Trans-

actions of Information Processing Society of Japan,

47(3):731–738.

Lang, P. J. (1995). The emotion probe: Studies of motiva-

tion and attention. American Psychologist, 50(5):372–

385.

Mathes, A. (2004). Folksonomy - cooperative classi-

fication and communication through shared meta-

data. Master’s thesis, Graduate School of Library and

Information Science University of Illinois Urbana-

Champaign.

Prendinger, H. (2004). Mpml : A markup language for con-

trolling the behavior of life-like characters. Journal of

Visual Languages and Computing, 15(2):183–203.

Takahashi, T., Bartneck, C., Katagiri, Y., and Arai, N.

(2005). TelMeA - expressive avatars in asynchronous

communications. International Journal of Human-

Computer Studies (IJHCS), 62(2):193–209.

Zajonc, R. B. (1968). Attitudinal effects of mere exposure.

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 9:1–27.

EFFECTIVENESS OF AVATARS FOR SUBJECTIVE ANNOTATION

81