BUILDING, AND LOSING, CONSUMER TRUST

IN B2C E-BUSINESS

Phil Joyce

Faculty of Information and Communication Technologies, Swinburne University, Melbourne, Australia

Graham Winch

The University of Plymouth Business School, Plymouth Universiy, Plymouth, England

Keywords: Trust, Business to Consumer eBusiness, System Dynamics.

Abstract: In the development of B2C eBusiness trust is an emerging key issue. Indeed, this has prompted the re-

examination of our current understanding of trust. The development of trust models have been mainly

developed from the traditional research basis of trust or from the multi-disciplinary perspective. Moreover,

these have been descriptive and static in nature but the building and losing of trust is a dynamic process. In

this paper we present a new perspective into the dynamic process of building and losing trust by presenting

a four element model to pictorially demonstrate the particular factors that driving the process.

1 INTRODUCTION

Today, the community as a whole are using Internet

technology, using websites, to enhance the provision

of goods and services through the usage of Business

to Consumer (B2C) eBusiness. Technology has

become more established in our daily lives and our

dependence on them grows, attention must turn to

the factors that impact on us all. Key among these is

trust.

As information, services or products are made

available electronically, researchers and practitioners

are focusing more intently on the factors of trust and

its impact. For many people B2C eBusiness (on-

line) is an encounter with new dimensions of

commerce compared with their traditional

experiences (off-line) of doing business (Corritore et

al., 2003, Gefen et al., 2003). The change from the

off-line to the on-line needs to be researched and the

impact on trust examined (Corritore et al., 2003,

Egger, 2000, Farrell et al., 2003, McKnight et al.,

2000, Winch and Joyce, 2006). The importance of

trust in the off-line world is well researched. The

fields of sociology, psychology, management,

marketing, human-computer interaction (HCI), and

electronic commerce all contribute to the rich

multidisciplinary nature. However, each producing

their own different concepts, definitions, models and

findings (Belanger et al., 2002, Corritore et al.,

2003, Farrell et al., 2003, Lewicki and Bunker,

1995, Tan and Thoen, 2001, Wicks et al., 1999).

Within each given field there is often a lack of

agreement (Lewicki and Bunker, 1995) but this

should not distract from the growing push to

developing a multidisciplinary approach to

understanding the factors of trust.

Consumer trust is acknowledged as a key element in

determining the success of B2C eBusiness offerings.

As a result, it has attracted research and many

models have been developed and published in the

literature. The purpose of this paper is not to present

yet another model, but to suggest how to move from

the information and knowledge those models

provide into a better understanding of the problem of

trust in B2C. Past models are largely descriptive and

static in nature. This work helps to give a new

understanding of trust building and maintenance as a

dynamic process within what is, in significant part, a

closed-loop system. The paper has therefore taken

the stock-flow diagramming approach from business

dynamics modelling to reflect the structure of the

trust building systems. This emphasises that the

management of system levels, such as trust, has to

be through the control of the in and outflows – if a

company needs to build trust it has to work through

55

Joyce P. and Winch G. (2007).

BUILDING, AND LOSING, CONSUMER TRUST IN B2C E-BUSINESS.

In Proceedings of the Ninth International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems - ISAS, pages 55-62

DOI: 10.5220/0002360500550062

Copyright

c

SciTePress

the flows resulting from consumers’ beliefs about

how and whether problems might arise.

The paper is structured in the following way with

section 2 we cover the background issues of trust

while in section 3 we outline the dynamic model to

highlight the forces that determine trust. In section 4

we discuss the management action plans to build and

maintain customer trust. Section 5 concludes the

paper.

2 BACKGROUND

As in the “real world”, trust is an important social

construct for cooperative behaviour. Trust enables

people to live in risky and uncertain situations and

also provides the means to decrease the complex

world by reducing the number of options a person

has to consider in a given situation (Deutsch, 1960).

Moreover, trust can be considered a shared principal

that allows coordination and cooperation between

people. This can be extended to the world of

business where trust is central in successful

transactions and the development of long term

relationships (Keohn, 1996). It is reasonable to

expect that the body of knowledge in off-line trust

(traditional) can help build a better picture of the key

issues of trust in the on-line environment by drawing

on the established off-line trust concepts.

An obvious commonality between off-line and on-

line trust is exchange (Baron and Byrne, 1991). In

the off-line environment risk, fear, complexity and

cost restrict exchange while coordination and

cooperation enhance exchange, it is likely that it will

also be similar in the on-line environment. Likewise,

social rules of interaction between people appear to

function in both on-line and off-line environments.

Similarly, it is reasonable that in the on-line world

the presence of trust in the person – website

interactions is essential for the success of the

transaction and/or discourse, especially in the B2C

scenario. For without trust, it is likely that an on-line

environment of B2C would not be possible, just as it

would not be possible in the off-line environment. In

essence, the fundamental factors of trust are seen in

both the off-line and on-line domain (Corritore et al.,

2003, McKnight and Chervany, 2001, McKnight et

al., 2000).

The trustor/trustee relationships are different as

technology mediates the interactions - transactions.

The situation in which trust is primarily person-to-

website rather than person-to-person communication

mediated through technology. In this paper, we will

focus on the person to website interaction. Trustors

and trustees, that is, objects of trust can be

individuals or groups, families, organisations, and

even societies. Moreover, in the B2C eBusiness

scenario we must not only consider the interaction of

the customer with the website but also the company

providing the processes to support the interactions.

The trustor/trustee relationships needs to extend not

only to the technology mediating the transaction but

also the company and its processes in support of the

on-line customer. This is made all the more difficult

if all communication is performed electronically

(on-line).

Interestingly, the definition between the trustor and

the objects of trust when technology is an object of

trust is a departure from the conventional off-line

view of trustor/trustee relationship. The fields of

psychology and sociology do not countenance the

concept of technology as an object of trust.

However, people do enter into relationships of

trustor with technology, web sites and computers

and they appear to respond to these technologies

based on the rules that apply to the social

relationship (Nass et al., 1996, Nass et al., 1995,

Nass et al., 1994). Indeed, the work by Nass, Reeves

and their colleagues highlight the responses to

computers by people were polite or rude, identified

them as assertive, timid or helpful, and had a

physical response to them. Interestingly,

technologies of this nature are viewed as social

actors in the sense that they have a social presence

that people respond to and interact with (Reeves and

Nass, 1996).

In summary, the use of technology (computers and

web site), especially in the B2C scenario, people see

them as social actors and interact with them in a

similar manner to that of off-line trust. Moreover, in

the B2C scenario they view the technology as a tool

that mediates the underlying process of gaining a

good, service or information from a business,

company or organisation.

2.1 On-line Trust

Trust is the act of the trustor. A person places trust

in an object, whether that trust is well founded or

not. Importantly, trust emanates from a person and

their trust, in part, it is formed by their perception of

the competence of that object to be trusted.

Moreover, trust is inextricably linked to risk in the

on-line environment. Wicks (1999) proposes trust as

the notion of an optimal level of risk whereby parties

are neither overly trusting and vulnerable, nor

mistrusting and missing legitimate opportunities.

Deutsch (1960) outlines trust as the willingness of

ICEIS 2007 - International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

56

an individual to behave in a manner that assumes

another party will behave in accordance with

expectations in a risky situation.

Of course, as Ruppel (2003) observes, when the

purpose of a website is simply to provide

information and promote products or services, the

visitor most probably perceives a smaller level of

risk which may require a lower level of trust to

function. However, if the site features functionality

that includes transaction processing, the risk is

increased. Therefore, the level of trust must rise to

reach a level of optimal trust where the increased

risk is manageable, acceptable and practical. At the

most basic level we assume that the trustor acts in a

trusting manner in a situation of risk when there is

little at stake (e.g., much money, very personal

information) and there are recognised systems of

reward and punishment. At the intermediate level, a

trustor has some experience and familiarity with the

web site, and so is in a situation of risk in which

knowledge can be used to predicate behaviour and

thus assign trust. Last in the development, which is

the deepest level of trust the trustor expects that his

of her interests will be respected by the website and

that he/she does not have to calculate the level of

risk anymore.

The building and losing of trust is a dynamic process

– people who are initially cautious can be persuaded

over time to be more confident in Internet-based

transactions and, conversely, people who start out

with an open-mind may become less trusting as

events and experiences unfold. Doney and Cannon

(1997), though talking about B2B dealings in

general are clear that developing and maintaining

trust is both a dynamic process and an essential

investment: ‘Supplier firms must make significant

investments to develop and maintain customer trust.

…. Our research suggests that though the process of

building customer trust is expensive, time-

consuming, and complex, its outcome in terms of

forging strong buyer-seller bonds and enhanced

loyalty could be critically important to supplier

firms, Doney and Cannon (1997), pg 48. ”

While here focussing on B2C interactions, this paper

tries to bring some new insights to these processes

by presenting models that inherently accept and

reflect their dynamic nature.

2.2 Trust and Trust Models in

E-business

A fundamental element of eBusiness transactions is

that the customers’ interaction with the supplier is

via an electronic interface not a person. As Gefen

and Straub (2003) observe, this lack of social

presence may impede the growth of B2C by

hindering the development of consumer trust in the

service provider. They also emphasise that human

interaction, or at least the belief that the system has

characteristics of social presence, is believed to be

critical in the creation of trust. They consequently

assert that managing e-services calls for managing

the trust that is engendered in the customer

experience on the website. But managing trust is

both a function of developing trusts but keeping trust

is also important because trust can be destroyed

(Lewicki and Bunker, 1995), and on the Internet,

retailers need to proactively (authors’ emphasis)

manage the trust component involved in selling

(Ambrose and Johnson, 1998).

The importance of trust has engendered much

research and the proliferation of models, many of

which have been tested against survey results. Some

authors have provided helpful comparative reviews

of models that have emerged from diverse

disciplinary backgrounds (Farrell et al., 2003).

While some have gone further by attempting to

integrate them into cross-disciplinary models (see

for example (Farrell, 2004), who proposes a further

multi-disciplinary trust model and (Keat and Mohan,

2004) who use the Davis’ Technology Acceptance

Model (TAM) as their foundation). It is not intended

in this paper to provide a further review. These

models are worthy and generally comprise a

catalogue of selected key trust supporting factors,

usually displayed graphically with lines, or

sometimes arrows suggesting connectivity. They are

however, short of providing a dynamic view and

limited in their abilities to provide helping tools for

helping managers to think about the processes and

building and maintaining consumer trust and

formulating strategies to improve it. For example,

(Pennington et al., 2003) comment that while

perceived trust in vendors has been shown to be an

important predictor of purchase behaviour, practical

guidelines on interventions to enhance consumer

perceptions is limited.

3 DETERMINING CUSTOMER

TRUST - A DYNAMIC

PERSPECTIVE

Trust is essentially a function of the possible

problems in using the Internet process envisaged by

potential purchasers and it is suggested here that a

BUILDING, AND LOSING, CONSUMER TRUST IN B2C E-BUSINESS

57

customer could be driven to sense possible problems

arising in these three ways:

Expected Problems - The building or depletion of

trust based on actual personal experiences – this will

be a function of the number of experiences and the

perceived quality of outcome that they feel they

experienced.

Hypothesised Problems – potential problems that

people believe might happen based on the perceived

risk of the transactions and individual companies

that they are dealing with. Indirectly, this will be

moderated by the actual risks or quantifiable risks.

Extrapolated Problems – problems that users might

expect resulting from their extrapolation based on

their use of technology, especially in support of

performing transactions. These are often “first time

users” who have analysed the technology and have

some knowledge of the technology. This maybe

good or bad and hence, this is about the transition of

customers entering into to the on-line environment

versus the off-line (traditional) environment and

understanding their problems.

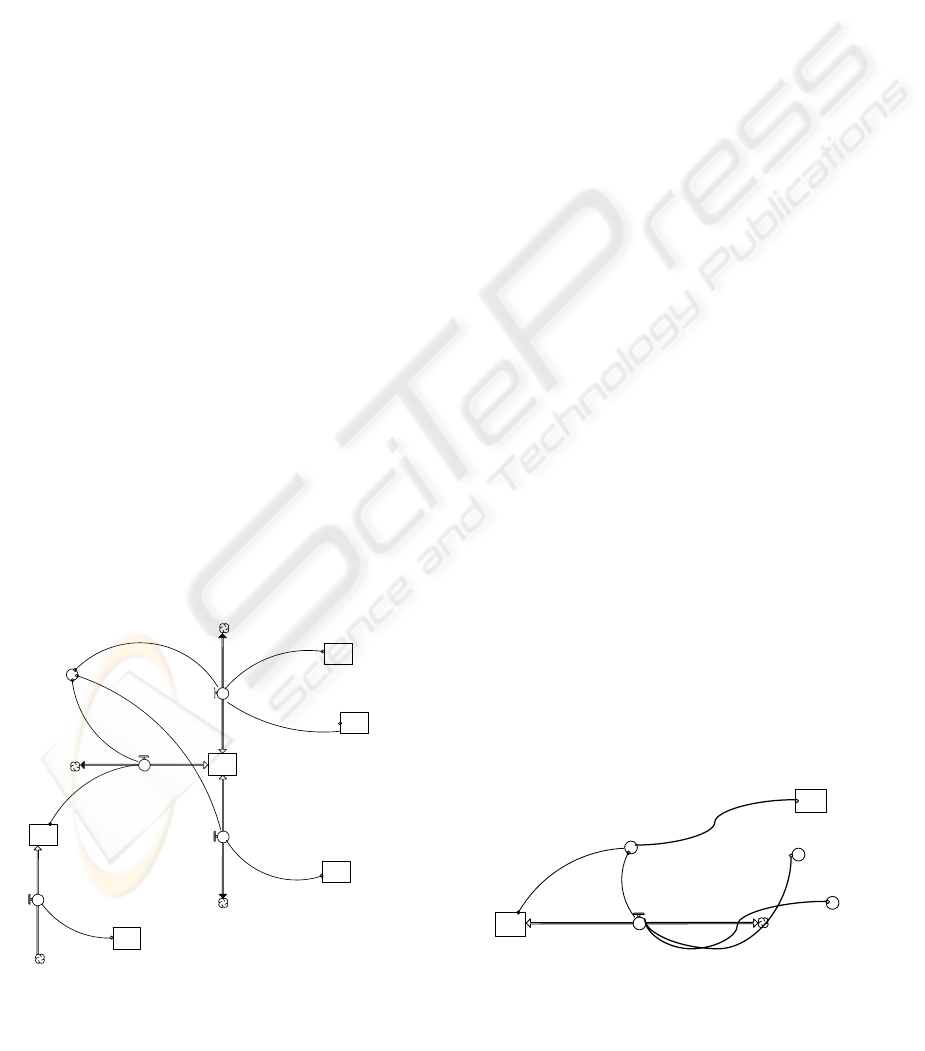

We suggest four simple inter-linked representations

to reflect the processes and interactions in the trust-

building system. We use the stock-flow structures

from system (or business) dynamics or process

control systems to capture the system structure; such

diagramming has been shown to support manager’s

understanding of complex dynamic processes (see,

e.g., (Sterman, 2000, Wolstenholme, 1990)) shows

that Trust – represented as a stock or reservoir - can

be added to or depleted through three flows – trust

derived from a consumer’s envisaged Expected,

Extrapolated, and Hypothesised Problems. These are

all bi-flows (two-headed flows) suggesting the

direction of flow can be either way – the level of

consumer trust can be built up or lost.

The primary driving forces for each of these are also

shown in Figure 1, and it is reflected that underlying

all the flows are an individual’s propensity to trust –

the intrinsic tendency of individuals to trust in others

(see, for example, (Egger, 2001, Grazioli and

Jarvenpaa, 2000, McKnight et al., 2000,

Papadopoulou et al., 2001)).

Change in trust from extrapolation is driven by the

customer’s technology understanding and their

development of a suitable knowledge level of the

technology. This requires an understanding of the

risk in utilising the technology. For example, a

purchase of a computer monitor, if we see the

customer is new to web technology but believes she

is capable of utilising the technology for the

purchase based on the knowledge that she has over

the technology. Without this knowledge, customers

are unlikely to utilise this approach in gaining

information, goods or service, which is central to

B2C eBusiness. As technology changes, from

eBusiness to mBusiness for example, different levels

of extrapolation (or knowledge base) must be

developed by the customer in order for them to

understand the risk and trust interplay. Similarly,

companies must emphasise the body of knowledge

to the customer and the relevance to them.

Once the customer has purchased on-line their

experience will inform their trust (risk) and therefore

reinforce or detract from knowledge they have

developed of the technology: Expected Problems.

The accumulated number of experiences and the

customer’s impression of the quality of those

experiences then also drive the change in trust from

experience. In both cases these maybe good or bad

experiences and importantly, a customer will draw

from their body of knowledge. For example, it may

be published information about ensuring a website

has a return policy clearly outlined on the website.

Initially, return policy maybe something a customer

may not understand or care about until they

TRUST

Change in Trust

from Experience

Change in trust

from Extrapolation

Change in Trust from

Hypothesised Problems

Propensity for

Trust

Knowledge Base

Knowledge Gain

Educational

Accumulated

Experiences

Perceived Risks

Perceived Quality

of Experiences

Programs & Activities

Figure 1: Inflows and Outflows from Customer Trust.

Perceived Risk

Change in

Perceived Risk

Actual or Quantifiable Risk

Risk Perception Gap

Risk Gap

Closure Time

Policy for Risk

Gap Closure

Figure 2: Working to Improve Perception of Actual Risks

towards the Perceived Risk.

ICEIS 2007 - International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

58

accumulate some experience with completing

purchases from a website in a B2C scenario.

Moreover, when a problem occurs the customer

focuses on both their experience and the body of

information for direction into how to solving the

problem.

The changes in trust from hypothesised problems are

those that are perceived by the customer. These may

or may not be based on the rationality. In this

scenario, cognitive and emotional trust is placed into

the domain of the hypothesised problems. The

customer can have cognitive trust where good

rational reasons as to why the object of trust merits

trust. While emotional trust is motivated by strong

positive feelings towards that which is being trusted

(Lewicki and Bunker, 1995). The change in

hypothesised problems is a mixture of cognitive and

emotional in nature. Consider an example of

purchasing a monitor. In this case, the company only

has an on-line presence and exists only as an on-line

company. If the company is a well-known company

such as amazon.com this may not be an issue of not

providing an off-line presence. In order to

understand further the forces in play, additions to

this basic model shown in Figure 1. Firstly, an

emphasis is that actual risk and perceived risk are

not the same thing but they are integrated in our

model. For example, a website might be completely

secure for credit card transactions, but is this fact

fully known and understood by visitors to the site.

Similarly, it is possible to provide the actual

statistical values (quantifiable) of the success of all

purchases from the web site. However, a customer

may not see the actual risk as equal to the perceived

risk. Hence, companies will be continually striving

to reduce the actual risks, but there will be a lag

between changes in actual and perceived levels.

Most B2C eBusiness systems are a way for an

organisation to provide goods and services and it is

important that management understand the customer

Perceived Risks in

eTransactions

Rate of change

of PR in

eTransactions

Quantifiable Risks

Related to eTransactions

Difference in

eTransaction

Risk

PR in eTransactions

adjustment time

Modulation in

eTransaction PR

Tailoring

Ease of Use

Informational

Content

Perceived Risks

in Company

Rate of change

of PR in

Compan

y

Quantifiable Risks

Related to Company

Difference in

Company Risks

PR in Company

adjustment time

Reputation

transfer of trust

Modulation in

Company PR

Company Perception :

size & ima

g

e

Links to

other sites

Reputation

Building

Branding

Amateurism

Testamonials

Hearsay

Privacy

Policy

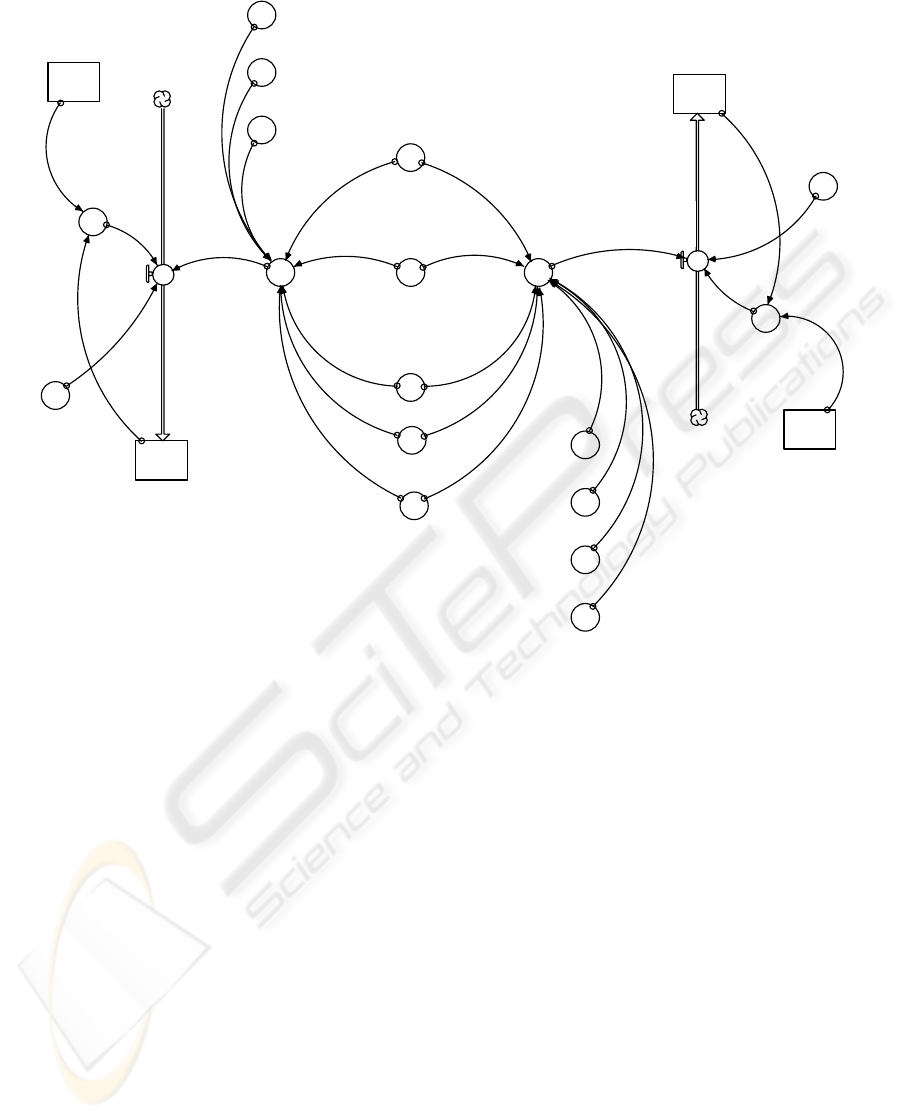

Figure 3: Factors Feeding into Perceived Risks in e-Transactions and in the Company.

BUILDING, AND LOSING, CONSUMER TRUST IN B2C E-BUSINESS

59

is interacting with them over a period of time to

complete the process. That is, the customer may

place an order for a product utilising a website

where they perform a transaction with the website.

However, customers and hopefully management are

also interested in the whole process of delivering the

good, information or service. The customer will be

interested in the next stage in the process of

providing the good, service or information. In this

we see that the transaction and the process as two

interrelated elements of the risk in B2C eBusiness.

In B2C both the e-transaction and the process

between the customer and company are important.

Indeed, customers may consider the risk of paying a

telephone bill utilising a power company’s website

small, even if their experiences have been poor in

utilising the website. Primarily, the power company

has processes in place that the customer is aware of

they can utilise to solve any problem that may arise.

This is similar to the eBay model of having dispute

processes in place even if the customers perceive the

risk in the transaction to be higher than normal.

Similarly, a customer may utilise a website to

perform an e-transaction even though they may

consider the organisation too risky to deal with.

Hence, the final element of the graphical model, the

factors believed to most influence actual and

perceived risks in both e-transactions and the

company can be brought together, shown in Figure

3. The existing literature and the range of descriptive

models available include a starting list of factors

such as this is beyond the scope of this paper. Farrell

(2004) and Farrell et al. (2003) provides a good

treatment of these factors that affect trust in the both

the e-transaction, company and its processes. Figure

2, shows the loss and gain (bi-flow) relationship

between the actual (or quantifiable) and perceived

risk highlighting the possible risk perception gap the

customer may perceive. The model shows a generic

risk adjustment mechanism emphasising two key

management variables that determine the

relationship between actual and perceived risk:

policy for risk gap closure and risk gap closure time.

The effort or emphasis placed on company

developing policies to narrow the perception gap and

the adjustment time by which companies would

want to bridge the gap. In this case, we can see that

management must develop policies that are capable

of influencing the customer to understand how the

actual (quantifiable) risks of their B2C offerings

have acceptable levels of risk. Similarly,

management must be aware that it will take time for

the message to be received, processed and acted on

by the customer.

Of course, the same factors might influence both

risks in e-transactions and in the company’s

processes, though clearly in the case of the former

the perception is going to be influenced to some

extent by experiences of other sites as well as with

the companies. This might take the form of simple

FAQ pages explaining principles and processes to

site users, through site use training, even to the level

of supporting formal education activities in

understanding computer and the Internet. The

model, in Figure 1, already suggests that a company,

acting either individually or in consortium with other

B2C providers, can directly influence consumer

trust, by supporting processes that educate

consumers in eBusiness processes. The diagram in

Figure 3 includes a starting list of factors form the

literature, but an individual company could tailor the

list to its own market place and offerings.

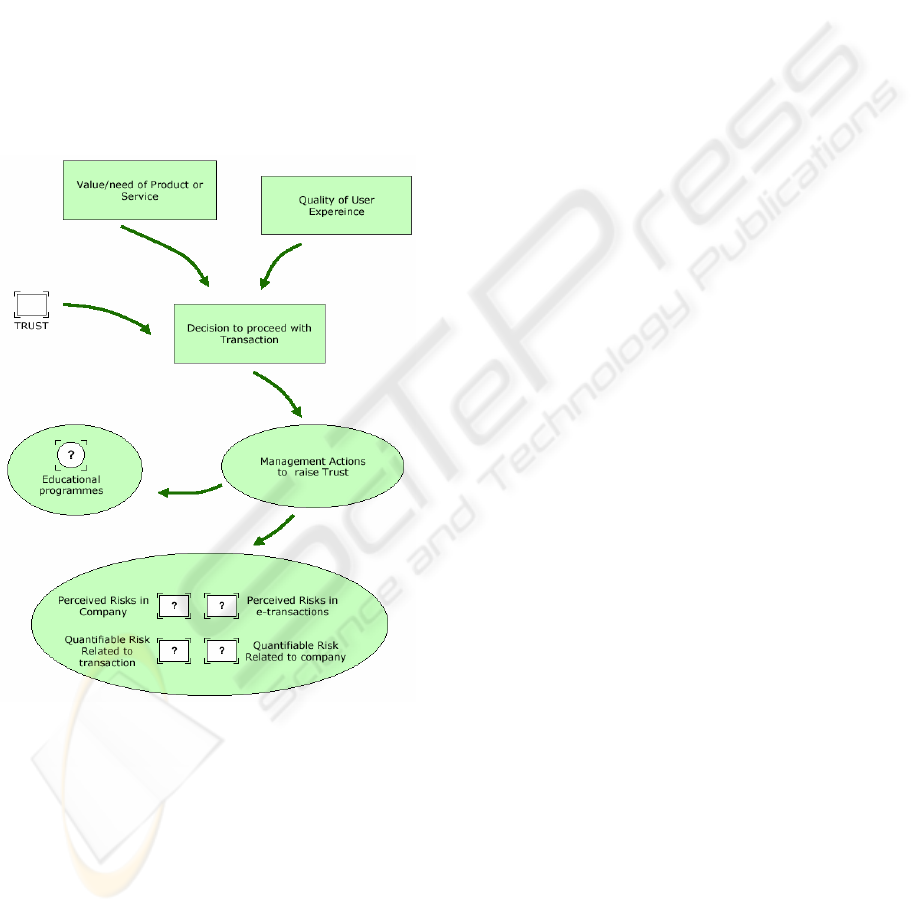

Figure 4: Completing the Management Action Loop.

ICEIS 2007 - International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

60

4 BUILDING AND MAINTAIN

THE LEVEL OF CONSUMER

TRUST - MANAGEMENT

ACTION PLANS

The mechanisms described above are to a significant

extent contained with in a closed-loop system. All

factors that feed into the trust building model in

Figure 1, with the possible exception of the

accumulated number of consumer experiences, are

factors over which a company has control or at least

partial control. Figure 4, therefore includes the

mechanisms that close the loops with the other

diagrams. It firstly reflects that any purchase

decision is at the conjunction of three factors – the

value or need for the product or service, the quality

of the user experience, and the potential purchaser’s

trust. The notion of optimal trust (Wicks et al., 1999)

links the value/need and trust factors, and also

reflects that, for example, a site that is only offering

information demands less trust of a visitor than a site

offering transaction functionality. The magnitude of

the purchase may also affect the risk/trust trade-off –

visitors might be more willing to risk losses in small

transactions than big ones (Cheung and Lee, 2001,

Corritore et al., 2003, Papadopoulou et al., 2001,

Tan and Thoen, 2001).

The resulting representation is presented in four

interlinked parts. The first reflects three basic in- and

out-flows to trust that will determine how trust

might be built, or lost. That is why consumers

believe problems could arise based on either the

expectation of problems derived form previous

personal experience, extrapolation from their

technical understanding of web-based activities, or

problems they hypothesise based on their perception

of the risks associated with e-transactions and

specific companies. The second gives a general view

of the relationship between actual and perceived risk

and that there is a company policy issue to do with

how and in what time frame they would want

consumers’ perceptions to follow reality. The third

element outlines the range of factors that could

influence actual or perceived risks relating to both e-

transactions, companies and its processes. This is a

suggested diagram based on the authors’ selected

factors from the literature, but other models and

research could be used as the starting point for this,

and the structure could be tailored to individual

companies’ situations. The final diagram suggests

that the loops are closed though a variety of

management actions and a coherent B2C trust

strategy should involve the exploration of the

balance of benefits deriving from combination of

actions and initiatives.

If we consider example of the purchase of the

computer monitor we can see the management

strategies that could help in moving customers from

visitors to purchasers by ensuring that that trust and

therefore, risks are addressed. Firstly, the company

should provide a core body of knowledge on the

technology used in the purchase, basic details of the

acceptable web site design, and the processes offer

by the company, e.g., dispute resolution procedures,

the details of return policies and procedures.

Similarly, the company should provide an outline of

the actual (or quantifiable) risks in using the site and

the statistics of the website (extrapolated problems).

This should allow the customer to adjust their

perceived risk in using the site and using this

company. Another loop that management can pursue

is to provide education programs. This education

program can allow customers to perform

transactions for goods, services or information for

free or minimal charge (expected problems). This

increases the customer’s user experience decreasing

the perceived risk in both the transaction, company

and its processes (hypothesised problem). Clearly,

the product, service or information must be of value

to the customer but

trust (and risk) must be managed by

the development of an on-line offering.

5 CONCLUSIONS

Building, and losing of consumer trust in a B2C

eBusiness is a dynamics process requiring all

stakeholders to consider the drivers and their impact

on consumer trust.

The four element model then suggests the cycle of

management actions the company must consider if

potential customers progressing to purchases is

unsatisfactory – can they reduce trust from

extrapolated problems by improving visitor’s

knowledge and understanding of web processes and

the processes of the organisation?

The paper provides a new perspective of the

complex problem and provides managers with a

possible checklist of potential drivers in the trust

cycle. Importantly, it does not provide a new model

but place some perspective on the current research in

the area of B2C consumer trust in eBusiness.

REFERENCES

Ambrose, P. J. & Johnson, G. J. (1998) A Trust Based

Model of Buying Behavior in Electronic Retailing.

BUILDING, AND LOSING, CONSUMER TRUST IN B2C E-BUSINESS

61

Americas Conference on Information Systems (ACIS

’98). Maryland.

Baron, R. A. & Byrne, D. (1991) Social Psychology:

Understanding Human Interation, Boston, Mass,

Allyn and Bacon.

Belanger, F., Hiler, J. S. & Smith, W. J. (2002)

Trustworthiness in electronic commerce: the role of

privacy, security, and site attributes The Journal of

Strategic Information Systems, 11, 245-270.

Cheung, C. & Lee, M. (2001) Trust in Internet Shopping:

A Proposed Model and Measurement Instrument.

Americas Conference on Information Systems (AMCIS

2001). Longbeach, California.

Corritore, C. L., Kracher, B. & Wiedenbeck, S. (2003)

On-line trust: concepts, evolving themes, a model.

International Journal of Human-Computer Studies,

58, 737-759.

Deutsch, M. (1960) The effect of motivational orientation

upon trust and suspicision. Human Relations, 13, 123-

139.

Doney, P. & Cannon, J. P. (1997) An Examination of the

Nature of Trust in Buyer-Seller Relationships. Journal

of Marketing, 61, 35-51.

Egger, F. (2000) Towards a Model of Trust for E-

Commerce System Design. Proceedings of Computer-

Human Interface CHI 2000. Zurich.

Egger, F. (2001) Affective Desing of E-Commerce User

Interfaces: How to Maximize Perceived

Trustworthyness. Conference on Affective Human

Factors Design (CAHD2001). Singapore.

Farrell, V. (2004) A Multidisciplinary Model of Trust in

B2C electronic Commerce. IFIP Working Group 8.4

Third Conference on E-business Multidisciplinary

Research. Saltzburg, IFIP.

Farrell, V., Scheepers, R. & Joyce, P. (2003) Models of

Trust in Business-to-Consumer Electronic Commerce:

A Review of Multidisciplinary Models. IFIP Working

Group 8.4 Second Conference on E-business

Multidisciplinary Research. Copenhagen, Denmark,

IFIP.

Gefen, D., Karahanna, E. & Straub, D. (2003) Trust and

Tam in Online Shopping: An Integrated Model. MIS

Quartley, 27, 51-90.

Gefen, D. & Straub, D. (2003) Managing User Trust in

B2C e-Services. e-Service Journal, 2, 7-34.

Grazioli, S. & Jarvenpaa, S. (2000) Perils of Internet

Fraud: An Empirical Investigation of Deception and

Trust with Experienced Internet Consumers. IEEE

Transactions on Systems, Man and Cybernetics, 30,

395-410.

Keat, T. K. & Mohan, A. (2004) Integration of TAM

Based Electronic Commerce Models for Trust.

Journal of American Academy of Business, 5, 404-

410.

Keohn, D. (1996) Should we trust in trust? American

Business Law Journal, 34, 164-176.

Lewicki, R. J. & Bunker, B. B. (1995) Trust in

Relationship: A Model of Development and Decline,

Jossey-Bass, San Francisco.

Mcknight, D. H. & Chervany, N. L. (2001) What Trust

Means in E-Commerce Customer Relationships: An

Interdisciplinary Conceptual Typology International

Journal of Electronic Commerce 6, 35 - 59.

Mcknight, D. H., Choudhury, V. & Kacmar, C. (2000)

Trust in E-Commerce Vendors: A Two Stage Model.

Proceedings of Twenty-First Annual International

Conference on Information Systems. Brisbane,

Australia.

Nass, C., Fogg , B. J. & Moon, Y. (1996) Can computers

be teammates? International Journal of Human-

Computer Studies, 45, 669-678

Nass, C., Moon, Y., Fogg, B. J. & Reeves, B. (1995) Can

computer personalities be human personalities?

International Journal of Human-Computer 45, 223-

239.

Nass, C., Steuer, J. & Tauber, E. R. (1994) Computers as

Social Actors. Conference on Human Factors in

Computer Systems (CHI 94). New York, US.

Papadopoulou, P., Kanellis, P. & Drakoulis, M. (2001)

Investigating Trust in E-Commerce: A Literature

Review and a Model for It s Formation in Customer

Relationships. Proceedings of Americas Conference

on Information Systems 2001. Boston, Massachusetts.

Pennington, R., Wilcocks, H. D. & Grover, V. (2003) The

role of System Trust in Business to Consumer

Transactions. Journal of Management Information

Systems, 20, 197-226.

Reeves, B. & Nass, C. (1996) The media equation: how

people treat computers, televesion, and the new media

like real people Stanford, CA., Cambridge University

Press.

Ruppel, C., Underwood-Queen, L. & Harrington, S. J.

(2003) e-Commerce. e-Service Journal, 2, 25-45.

Sterman, J. D. (2000) Business Dynamics: Systems

Thinking and Modelling for a Complex World,

McGraw-Hill.

Tan, Y.-H. & Thoen, W. (2001) Toward a Generic Model

of Trust for Electronic Commerce. International

Journal of Electronic Commerce 5, 61 - 74.

Wicks, A. C., Berman, S. L. & Jones, T. M. (1999) The

Structure of Optimal Trust: Moral and Strategic

Implications. Academy of Management Review, 21,

99-116.

Winch, G. W. & Joyce, P. (2006) Exploring the dynamics

of building, and losing, consumer trust in B2C

eBusiness. International Journal of Retail and

Management, 34, 541-555.

Wolstenholme, E. (1990) System Enquiry: A System

Dynamics Approach, Chichester, John Wiley & Sons.

ICEIS 2007 - International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

62