Home Monitoring in Portugal

An Overview on Current Experiences

Ana Dias

1

, Madalena Vilas Boas

1

, Daniel Polónia

1

, Alexandra Queirós

2

and Nelson Pacheco Rocha

3

1

Department of Economics, Management, Industrial Engineering and Tourism, University of Aveiro,

Campo Universitário de Santiago, 3810-193 Aveiro, Portugal

2

Health Sciences School, University of Aveiro, Campo Universitário de Santiago, 3810-193 Aveiro, Portugal

3

Department of Medical Sciences, University of Aveiro, Campo Universitário de Santiago, 3810-193 Aveiro, Portugal

Keywords: Telemedicine, Teleconsultation, Home Monitoring, Portuguese National Health Service.

Abstract: This paper aims to be a contribution to the discussion on the issue of innovation in healthcare since, in the

author’s perspective, the health sector, and particularly the Portuguese National Health Service, needs

changes in its "business model". There is a need of redirecting care provision to the citizen’s natural

environment, namely considering the opportunities offered by information and communication

technologies. For this purpose the authors surveyed projects already implemented in Portugal, within the

Portuguese National Health Service, related to home monitoring, in order to make a critical analysis of the

state of the art of ongoing projects. In this study, the authors identified four pilot experiences of home

monitoring, all targeted at chronic disease. In spite of some results of these experiments are already known,

there is a shortage of available information and scientific evidence, both about the implementation processes

themselves and about their clinical, technical and economic evaluation, which, in the opinion of the authors,

also hinders their assessment and dissemination.

1 INTRODUCTION

The Portuguese National Health Service (Serviço

Nacional de Saúde - SNS) presents difficulties in the

coordination between levels of care, particularly

among primary healthcare and hospital care, which

has an impact on patient access to healthcare (Barros

and Simões, 2007).

Traditionally, acute diseases were the main

concern of health systems, a situation that has

changed over the last century, as a result of advances

in biomedicine and public health, with a significant

impact on the eradication of certain infectious

diseases. What is questioned today is whether, with

regard to the organizational model of health systems,

they fit the current reality where chronic diseases are

predominant (Dias, 2015).

Data from the National Health Survey (INS,

2014) are indicative of the new challenges of the

Portuguese SNS. In 2014, more than half (52.8%) of

the population aged 18 years, was overweight

(50.9% a decade ago). The symptoms of depression

also worsened, affecting more the retired population

(36.5% of the retired population had symptoms of

depression, compared to 18,5% of the employed

population). Also the percentage of people who

reported consuming prescribed drugs increase

sharply with age: more than 90% of the population

over 65 years. Comparing the results for chronic

diseases collected in two surveys (2005-2006 and

2014) it is clearly an increase of the percentage of

population affected by these diseases (INS, 2014).

The aging process that the Portuguese population

is suffering further enhances this scenario. The

National Statistics Institute (Instituto Nacional de

Estatística - INE) forecasts that the potential

sustainability index (i.e. the ratio between the

number of people aged between 15 and 64 and the

number of people aged 65 and over) may decrease

abruptly: in Portugal, between 2012 and 2060, this

index, in one of the most likely scenarios can change

from 340 people in working-age for every 100

elderly to 149 people in working-age for every 100

elderly, a value that can decrease to 111 people in

working-age for every 100 elderly in the worse-case

scenario (INE, 2014a).

We are at a very particular moment of our

history in which a "demographic transition” is

Dias A., Vilas Boas M., Poløsnia D., Queirøss A. and Pacheco da Rocha N.

Home Monitoring in Portugal - An Overview on Current Experiences.

DOI: 10.5220/0006220603770382

In Proceedings of the 10th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2017), pages 377-382

ISBN: 978-989-758-213-4

Copyright

c

2017 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

377

combined with “an epidemiological transition" and

"this combination of phenomena is confronting us

with a crisis (…) which comes as an opportunity to

look critically at what has been done and, based on

that, project us in the future with more appropriate

tools and skills to new circumstances." (OPSS, 2016,

p. 31).

This study thus seeks to contribute to the

discussion on the theme of innovation in healthcare

in Portugal, taking advantage of the opportunities

offered by information and communication

technologies. In particular, given the home

monitoring potential, which is supported on the

progress achieved in mobile technologies, as well as

its relevance to chronic diseases, this study aims to

analyze the viability of experiences already

implemented in Portugal related to home monitoring

of patients with chronic diseases.

2 RELATED WORK

In Portugal, via the 3571/2013 Order, published in

the Official Gazette on March the 6

th

, 2013, the

Ministry of Health, assuming that the use of

telemedicine allows the observation, diagnosis,

treatment and monitoring in a more convenient place

for patients, particularly at home, states that "the

services and facilities of the National Health Service

(SNS) should increase the use of information and

communication technologies in order to promote and

ensure the provision of telemedicine services to [its]

users" (p.8326).

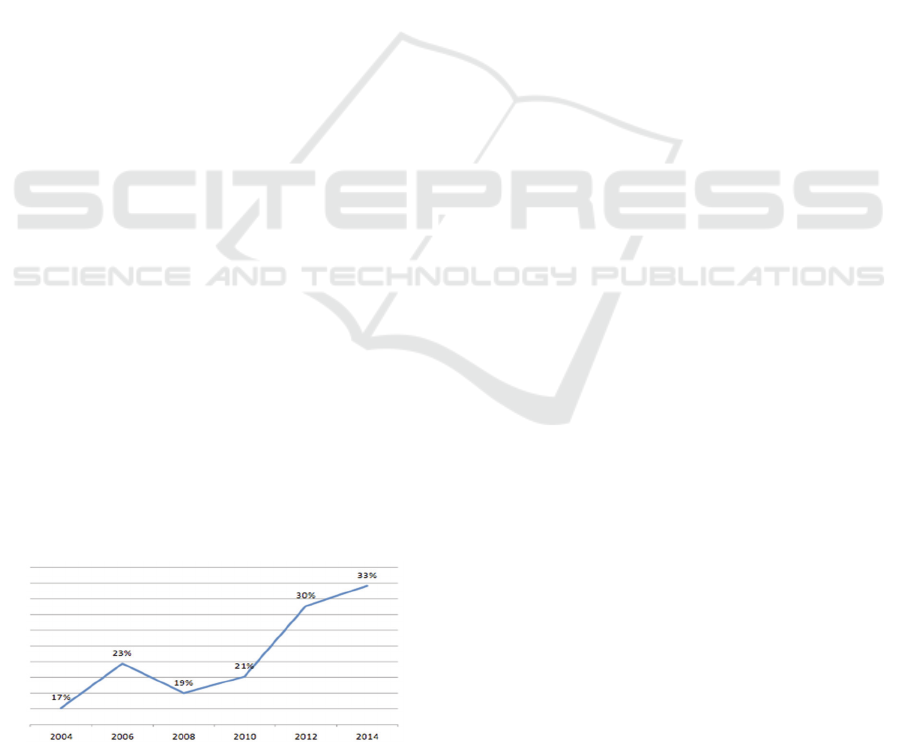

According to INE, on its Survey on the Use of

Information and Communication Technologies in

Hospitals (INE, 2014b), one third of the Portuguese

hospitals developed telemedicine activities in 2014,

an increase of 16 percentage points in ten years (12

percentage points in the last four years) (Figure 1).

However, the degree of implementation of

telemedicine is quite different in public hospitals

(51%) and private hospitals (15%).

Figure 1: Proportion of hospitals with telemedicine,

Portugal, 2004-2014 (Source: INE, 2014b).

Telemedicine activity can take many forms,

ranging from remote diagnosis (teleradiology and

telepathology) to remote care provision, such as

teleconsultation or home monitoring. Within

telemedicine activities, the most used was

teleradiology (i.e. the exchange of images to discuss

cases and for diagnosis), being reported by 84% of

hospitals that refer having telemedicine. On the

other hand, only 31% of hospitals that report having

telemedicine provide teleconsultation (i.e. 10% of

the total hospital’s number) (INE, 2014b).

As a result of the telemedicine development,

Portugal is involved in several international projects

to promote the cooperation between healthcare

professionals. In particular, there are some projects

with the African Countries with Portuguese as an

Official Language (Países Africanos de Língua

Oficial Portuguesa - PALOP) (Borja-Santos, 2013).

In October 2013 it was launched a telemedicine

platform between Portugal and several PALOP

(Noronha, 2013) but, previously, there were other

projects. For example, in 2012 a project between

Portugal and São Tomé and Príncipe allowed an

estimated saving of 180,000 euros in the transfer of

patients to Portugal and allowed to save one million

euros to the Portuguese Ministry of Health

(Noronha, 2013). Portugal is also part of a

telemedicine network with Angola and the

University Hospitals of Geneva that allows technical

support for diagnosis and treatment of Angolan

patients.

In addition to the experiences within the PALOP,

there are others being carried out between Portugal

and Spain. Since 2003 the southern region of the

Algarve has participated in a telemedicine project in

conjunction with the Spanish region of Andalusia,

with the aim of creating new communication

channels between the Algarve and Andalusia and,

inside the Algarve, between the health centers and

the hospitals in the region, with the installation of

telemedicine equipment in all health centers (Portal

da Saúde, 2005).

With regard to teleconsultation, in 2007, it was

launched in Portugal the “Linha de Saúde 24”,

which provides counselling and referral in a disease

situation, accessible through the phone (or chat for

people with special needs) as well as therapeutic

counselling to clarify particular questions and

provide support related to matters as medication

(Saúde 24, s.d.).

Within a group of other innovative projects in

this area, out of the governmental sphere, the authors

highlight two: the "Patient Innovation", a social

network for patients who, sharing experiences about

HEALTHINF 2017 - 10th International Conference on Health Informatics

378

their illness, can develop solutions to their real

problems, from therapeutic support to proper

medical equipment (Pinho, 2013) and a private

service that allows traveler teleconsultations

(Consulta do Viajante, 2016).

Specifically, in the region of Alentejo (one of the

most aged and sparsely populated regions of the

country) several teleconsultation experiments

(Oliveira et al., 2014) were reported, dating back to

1998, in order to respond to challenges such as

desertification, isolation, low population density,

poverty, lack of medical resources in several

specialties as well as poor public transports, all of

which have acted as barriers to access to healthcare

in the region. It should be noted that the Alentejo

region represents approximately one-third of

Portugal’s continental territory, but it is home to

only 5% of its population. Teleconsultations are

available in 15 medical specialties, ranging from

Neurology to Pediatric Surgery. The network

includes 20 primary care units and five hospitals,

covering almost 30,000 km

2

and around 500,000

people. A comprehensive assessment of the costs

and consequences of the program is currently

underway, since it is stated that there is a lack of

evidence of its cost-effectiveness, which, according

to Oliveira et al. (2014), hinders the sustainment and

realization of the promise of innovative solutions,

wherever it is implemented.

Regarding the autonomous islands, the Azores

already belongs to several networks, which allows

the realization of teleconsultation to determine the

clinical need of the patient's displacement to

mainland to carry out consultations and exams

(Mourato, 2014). In the Azores the use of

teleconsultation in Nursing is also frequent,

particularly in decision support in the treatment of

wounds. Furthermore, there is already

teleconsultation in various health centers in the

archipelago in the following specialties:

Nephrology, Pediatric Cardiology, Neonatology and

Endocrinology.

Home monitoring can improve disease

prevention, facilitate chronic disease management,

including disease self-management, enable

personalization of care, and improve productivity in

healthcare, thus allowing a more rational use of

health services (Queirós et al., 2013; Queirós et al.,

2017). In Portugal, according to the Order

8445/2014 of June the 30th, 2014, the Ministry of

Health stressed the need to improve the capacity of

health monitoring, prevention, detection and

treatment of disease in innovative ways, including

through models of care in order to maintain people

in their homes, promoting their autonomy and

encouraging personal responsibility by adopting

healthy lifestyles. However, there are no studies

reporting the current experiences of home

monitoring in Portugal.

3 METHODS

Considering the lack of evidence of current

Portuguese home monitoring experiences, the

present study has the following main objectives:

To make an inventory of projects already

implemented in Portugal, within the SNS in

the area of home monitoring, particularly

focused on the chronically ill, and preferably

projects involving primary healthcare, which

is believed that will assume an increasingly

central role in the management of chronic

disease.

To make a critical analysis of the state of the

art of ongoing projects.

The authors consulted the Central Administration

of the Health System (Administração Central do

Sistema de Saúde - ACSS) in order to retrieve

information on projects related to home monitoring

already implemented by the SNS.

Subsequently, an additional survey was

conducted to analyze if there were publications that

best described these experiences and others in the

same area, and possible results already obtained.

Finally, the authors conducted a survey on the

web pages of SNS hospitals to search for innovative

projects in general, and home monitoring in

particular. For this purpose, the web pages of 41

hospitals were identified and analyzed.

4 HOME MONITORING

EXPERIENCES IN PORTUGAL

With data provided by the ACSS it was possible to

identify three projects related to home monitoring

already implemented by the Portuguese SNS. In the

area of Pulmonology, a home monitoring pilot

program of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

was developed, funded by the ACSS and supported

by Shared Services of the Health Ministry (Serviços

Partilhados do Ministério da Saúde - SPMS), the

government agency for eHealth, in partnership with

five hospitals, covering a total of 75 patients with

severe disease (15 per hospital). These patients were

selected in each hospital by their attending

Home Monitoring in Portugal - An Overview on Current Experiences

379

physician, based on their prior history of chronic

obstructive pulmonary disease. This home

monitoring pilot program began in 2013 and was

implemented in a phased manner in the five

institutions, namely: Hospital of Faro (Algarve) -

beginning in August 2013 (Phase 1); Hospital Pêro

da Covilhã (Cova da Beira) - beginning in March

2014; Hospital and University Center of Coimbra -

beginning in May 2014; Hospital of Viana do

Castelo (Alto Minho) - beginning in October 2014

and Hospital of Portalegre/Elvas (North Alentejo) -

beginning in October 2014. Five private companies

were also involved in the project and were

responsible for the installation of the monitoring

devices and their maintenance and for the process of

gathering information and transfer it to health

professionals. Each patient was assigned the

following monitoring devices: blood pressure

measuring device, pulse oximeter, thermometer,

odometer, device monitoring heart rate and mobile

phone. The clinical teams of the hospitals were

actively involved in the monitoring of patients

integrated in the program and also in their education.

According to SPMS (2014), under this pilot

program, patients are monitored in their homes. The

respective data are then analyzed twice a day by the

Pulmonology teams of involved hospitals, trying to

reduce the aggravation of their clinical situation,

thus avoiding new hospital admissions.

The objectives and results to be achieved in 2016

within the home monitoring program for chronic

obstructive pulmonary disease include (ACSS,

2016): raising the quality of services provided to

citizens, promoting the continuous monitoring of

their health condition; reducing at least one episode

of annual hospitalizations as a result of the

deterioration of the patients medical condition;

reducing at least three episodes of urgency per year;

reducing at least two episodes of outpatient

consultation per year, and follow, proactively and

continuously, the fluctuations of the health

conditions of each patient.

In terms of preliminary results of this pilot

program, according to Pereira (2016), these have

been encouraging, both in terms of satisfaction and

health indicators, having already been released some

results of an evaluation carried out in the Local Unit

of the Alto Minho, namely the reduction in 50% of

visits of these patients to emergency services, as

well as a decrease in the number of hospitalizations

(70%). Pereira (2016) also states that in these five

hospitals, 61% of patients considered the quality of

the service as "very good or excellent”. Although the

final overall results are not yet available due to the

late start in one of the hospitals, interim evaluations

reveal both a reduction in the number of hospital

admissions or visits to the urgency services of

patients, more evident in some hospitals.

More recently, in November 2015, the “Home

Monitoring Plan” was adopted for the definition of

sites for the realization of home monitoring and its

articulation with the rules of the SNS.

In this context, and for the year 2016, it was

contracted activity for the implementation of other

two home monitoring pilot programs: a Pilot

Program for Home Monitoring of Acute Myocardial

Infarction and a Pilot Program for Chronic Heart

Failure. Like the pilot program of chronic

obstructive pulmonary disease, it was planned that

the program would be implemented in five hospitals

covering a group of 75 patients (15 per hospital).

In the case of the chronic heart failure, and in the

absence of results which can be explained due to the

program's newness, it should be noted that from

conventional remote monitoring to more recent

strategies, using cardiac devices or implantable

hemodynamic monitors, this is a topic under active

investigation, but, despite previous meta-analyses of

small studies have documented the potential benefit

of home monitoring, major randomized clinical trials

have failed to demonstrate the positive impact of this

strategy. In addition, data on the value of the latest

monitoring devices are contradictory, since some

studies have documented potential prognosis benefit

while others cannot confirm it (Sousa et al., 2014).

As a result of the literature review carried out in

scientific databases, the authors found a concrete

example in Portugal of assessment of a home

monitoring experience in cardiac patients, with four

hospitals involved. This study, of 2013, indicates

that the introduction of home monitoring has the

ability to reduce in 25% the costs of monitoring the

patients (Costa et al., 2013).

To broaden the scope of this research, and to

identify innovative projects, in general, and home

monitoring, in particular, the authors decided to

search for information on the web pages of the SNS

hospitals. From the 41 organizations identified six

refer teleconsultation activities on the following

areas: Dermatology (referred by three

organizations), Pediatric Cardiology (two

organizations), Internal Medicine, Endocrinology,

Rheumatology, Oncology, Neurosurgery, Pediatrics,

Gynecology, Ophthalmology, Genetics, Imaging and

Pathology (all referred only by one organization).

However, no organization mentions any home

monitoring experiment.

HEALTHINF 2017 - 10th International Conference on Health Informatics

380

5 DISCUSSION

The main purpose of this study was to give visibility

to the experiences already implemented in Portugal

related to home monitoring of patients with chronic

conditions, which the authors believe could permit

not to repeat known errors as well as to replicate

successes, after being properly evaluated and

contextualized. However, it is clear that, although

some results of these experiments have been

reported in this paper, there is a shortage of

scientific evidence regarding, on one hand, the

implementation process and, on the other hand, the

evaluation of these experiences, what is conflicting

to what is defended in the eHealth Action Plan 2012-

2020 - Innovative healthcare for the 21st century

(Commission of the European Union, 2012),

namely: “It is essential to measure and assess the

added value of innovative eHealth products and

services to achieve wider evidence-based eHealth

deployment and create a competitive environment

for eHealth solutions.” (p.13)

Regarding the home monitoring pilot projects

identified in this work the authors would like to

stress that the pathologies covered by the pilot

projects correspond to chronic diseases and that they

are also within the group of priority areas identified

by the Portuguese government in 2013.

Concerning these same projects the authors also

want to highlight the fact that in the group of

institutions covered by these projects, there are no

institutions coming from primary healthcare, at least

not in an explicit and formal way. As mentioned

before, the authors consider that the primary

healthcare services must increasingly be involved

because of their close proximity to the patient and

their informal careers as well as due to their abilities

in the management of chronic disease, even because

one of the main purposes of home monitoring is to

reduce the number of admissions or visits to the

hospital emergency services. It is important to

emphasize the significance of primary healthcare in

the organization of health systems, recalling what in

1978 was stated in the Declaration of Alma Ata

(WHO, 1978) on the importance to be given to this

level of care: “Primary healthcare is essential

healthcare based on practical, scientifically sound

and socially acceptable methods and technology

made universally accessible to individuals and

families in the community through their full

participation and at a cost that the community and

country can afford (…) It is the first level of contact

of individuals, the family and community with the

national health system bringing healthcare as close

as possible to where people live and work, and

constitutes the first element of a continuing

healthcare process.” (p.1-2)

Concerning the results obtained from the

research on the hospital’s web pages, the authors

would like to highlight the scarce information

available with regard to innovative experiences, as

well as the complete lack of publicizing information

about home monitoring. This, from the author’s

point of view, can raise questions in particular

regarding the opportunities created for patients to

participate in these experiences and create obstacles

to ensure the equity required in healthcare provision.

Despite the fact that, as it has also been

demonstrated in this work, home monitoring

experiences in Portugal are still small, in number

and in size, still the authors would like to discuss the

importance of what is (or not) revealed to the public:

whether information regarding the experiences as a

whole whether information on the criteria for

inclusion of patients in these experiments. Another

purpose of this advertising is, from the author’s

point of view, to emphasize the need to make the

whole process more transparent, with particular

interest to patients and also to other health

professionals and institutions, a similar progress that

what has been achieved with respect to clinical trials

since 2011. Since then, the information on clinical

trials with medicines for human use, which are

underway in the European Union, is accessible to all

European citizens from the portal "EU clinical trials

Register" and, more recently, through the

international network of clinical trials registers of

the World Health Organization. In Portugal, Law

21/2014 of the 16th April, amended by Law 73/2015

of the 27th July, envisages the creation of the

National register of clinical trials. Still, and going

back to experiences that are developed within the

SNS in Portugal, and highlighting once again the

difficulties, specifically in this study, on the

collection of information on ongoing initiatives, the

authors would like to discuss the pertinence of

creating a platform for registering, monitoring and

disseminating results of these experiences, similar to

what is already being done in the clinical trials

domain.

6 CONCLUSION

In Portugal, within the SNS, the authors identified

four pilot experiences of home monitoring, all

targeted at chronic disease, but with no direct

involvement of primary healthcare, at least explicit

Home Monitoring in Portugal - An Overview on Current Experiences

381

in contracts that were made between the ACSS and

the primary healthcare services. This somehow

contradicts the need to direct primary care for the

prevention, with a view to achieve further gains in

health outcomes as well as improvements in terms of

efficiency.

The authors would also like to point out the

difficulty in getting information related to home

monitoring experiences taking place in the SNS,

from one source, which, from our point of view,

should be either the ACSS or the SPMS. In the

author’s point of view, if this information is not

someway centralized, the evaluation and subsequent

dissemination of these experiences will be more

difficult to achieve.

It should also be noted that it was not possible to

identify evaluation methods with the purpose of,

systematically, evaluating experiences, so that the

decisions can be based on accurate information, it

can be possible to learn from mistakes as well as to

innovate by sharing and replicating successful

experiences, although this is one of the EU

guidelines for the eHealth Action Plan 2012-2020

(Commission of the European Union, 2012).

REFERENCES

ACSS (2016). Termos de referência para contratualização

hospitalar no SNS – Contrato Programa 2016.

Barros, P. P. and Simões, J. D. A. (2007). Health systems

in transition: Portugal – Health system review. The

European Observatory on Health Systems and

Policies.

Borja-Santos, R. (2013). Ministério quer que serviços de

saúde apostem mais na telemedicina. Jornal Público.

Available in:

https://www.publico.pt/sociedade/noticia/ministerio-

quer-que-servicos-de-saude-apostem-mais-na-

telemedicina-1586809.

Commission of the European Union (2012). eHealth

Action Plan 2012-2020 - Innovative healthcare for the

21st century.

Consulta do Viajante (2016). Available in:

http://www.consultadoviajante.com/sobre.html.

Costa, P. D., Reis, A. H. and Rodrigues, P. P. (2013).

Clinical and economic impact of remote monitoring on

the follow-up of patients with implantable electronic

cardiovascular devices: An observational study.

Telemedicine and e-health, 19(2), pp. 71–80.

Dias, A. (2015). Integração de cuidados de saúde

primários e hospitalares em Portugal: uma avaliação

comparativa do modelo de unidade local de saúde

(Tese de Doutoramento). Universidade de Aveiro,

Portugal.

INE (2014a). Projeções de População Residente 2012-

2060. Lisboa: Instituto Nacional de Estatística.

INE (2014b). Inquérito à utilização das tecnologias de

informação e da comunicação nos hospitais 2014.

Lisboa: Instituto Nacional de Estatística.

INS (2014). Inquérito nacional de saúde 2014. Available

in:

http://www.insa.pt/sites/INSA/Portugues/ComInf/Noti

cias/Documents/2015/Novembro/11INS2014.pdf.

Mourato, P. (2014). Telemedicina generaliza-se até final

do ano. Available in:

http://www.dn.pt/portugal/acores/interior/telemedicina

-generalizase-ate-final-do-ano-3960209.html.

Noronha, N. (2013). Rede de telemedicina entre Portugal e

PALOP avança em 2014. Available in:

http://lifestyle.sapo.pt/saude/noticias-

saude/artigos/rede-de-telemedicina-entre-portugal-e-

palop-avanca-em-2014.

Oliveira, T.C., Bayer, S., Gonçalves, L., and Barlow, J.

(2014). Brief Communication-Telemedicine in

Alentejo. Telemedicine and e-Health. 20 (1)

OPSS (2016). Relatório de Primavera 2016 - Saúde:

Procuram-se novos caminhos. Observatório Português

dos Sistemas de Saúde. Available in:

http://www.opss.pt/node/488.

Pereira, J. (2016). Telemedicina em Portugal.

NewsPharma MyPneumologia. Available in:

http://www.mypneumologia.pt/entrevistas/208-

telemedicina-em-portugal.html

Pinho, L. (2013). Patient Innovation é uma rede social

para doentes. Jornal Público. Available in:

http://p3.publico.pt/actualidade/ciencia/8400/patient-

innovation-e-uma-rede-social-para-doentes.

Portal da Saúde (2005). Portugal e Espanha implementam

a Telemedicina no Algarve. Available in:

http://www2.portaldasaude.pt/portal/conteudos/a+saud

e+em+portugal/investigacao+e+desenvolvimento/tele

medicina.htm.

Queirós, A., Carvalho, S., Pavão, J., Da Rocha, N.P.

(2013). AAL information based services and care

integration. In HEALTHINF 2013 - Proceedings of the

International Conference on Health Informatics, pp.

403-406. ISBN: 978-989856537-2.

Queirós, A., Pereira, L., Dias, A. and Rocha, N. (2017).

Technologies for Ageing in Place to Support Home

Monitoring of Patients with Chronic Diseases. In

HEALTHINF 2017 - Proceedings of the International

Conference on Health Informatics

.

Saúde 24 (s.d.). Quem somos. Available in:

http://www.saude24.pt/PresentationLayer/ctexto_00.as

px?local=15.

Sousa, C., Leite, S., Lagido, R., Ferreira, L., Silva-

Cardoso, J., and Maciel, M.J. (2014). Telemonitoring

in heart failure: A state-of-the-art review. Revista

portuguesa de cardiologia, 33(4), pp.229-239.

SPMS (2014). Telemonitorização DPOC. Available in:

http://spms.min-saude.pt/2014/04/telemonitorizacao-

dpoc-2/.

WHO (1978). Declaration of Alma-Ata. International

Conference on Primary Health Care, Alma-Ata,

USSR, 6-12 September 1978.

HEALTHINF 2017 - 10th International Conference on Health Informatics

382