Identifying Key Components of Services in Healthcare

in the Context of out-Patient in Norway

Eunji Lee

SINTEF, Oslo, Norway

Keywords: Service Design, Healthcare, eHealth.

Abstract: This paper discusses components of service in healthcare. Four components of a service (service customer,

service worker, service setting and service process) were introduced. Yet these components have not been

explored in healthcare cases. We identified the key components through our case study with out-patient

histories, involving electronic health record systems. Based on our analysis we propose a set of components

to be considered for designing stakeholder-centred services in healthcare. The result of this study might be

useful to the health informatics researchers to better understand the service interactions in today’s healthcare

in a more analytic and holistic way by taking the service engineering perspective, at the same time to the

service engineering or design researchers to have a deeper insight of the services in healthcare and the

components to be considered when designing the services.

1 INTRODUCTION

The service delivery process in healthcare is

complex (Reichert, 2011); designing healthcare

services can therefore be challenging. Healthcare

services involve many actors, who work with

different agendas, have highly specific knowledge,

and who have tasks that are intertwined with other

organisations. eHealth, a healthcare service that is

supported by telecommunications and information

technology (Mitchell, 2000), complicates the service

delivery process even further. While eHealth

technologies break down barriers of time and place,

thus bringing people and resources together to

provide healthcare services in more efficient ways

(Hesse and Shneiderman, 2007), it also generates

various interactions between many actors and

systems which were absent in conventional health

service situations.

Involving eHealth technologies in today’s

healthcare service is not uncommon. For instance,

while a patient has a consultation with his/her

general practitioner (GP), the GP looks up the

information from the previous consultation(s)

through an electronic health record (EHR) system.

The use of such technology changes the healthcare

practices and consequently can affect patient’s life

(Rodolfo et al., 2014). Therefore, there is a need to

understand the complex service delivery process in

healthcare in an analytic and holistic approach. Such

approach might contribute to better assess the

existing services in healthcare, which can be a

starting point for designing improved services.

Gadrey (2002) introduced three components of a

service: service provider, customer/client/user, and

transformation of a reality. Fisk et al. (2013)

presented and defined four components of service

and the definitions are as below.

• Service customer: the recipient of the service

• Service worker: the contributor of the service

delivery by interacting with service customer

• Service setting: the environment in which the

service is delivered to the customer

• Service process: the sequence of activities

essential to deliver the service

Yet these components have not been fully

explored in today’s complex healthcare settings. Our

research question is “What are the key components

in out-patient services?”

The rest of this paper is organised as follows: We

first describe our research approach, context,

methodology, and methods for data collection and

analysis in Section 2. In Section 3, we introduce two

out-patient histories. We then present the results

from our analysis in Section 4 and discuss the results

in Section 5. In Section 6, we discuss the limitations

of this study. Finally, we conclude our study and

suggest future research in Section 7.

354

Lee E.

Identifying Key Components of Services in Healthcare in the Context of out-Patient in Norway.

DOI: 10.5220/0006170803540361

In Proceedings of the 10th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2017), pages 354-361

ISBN: 978-989-758-213-4

Copyright

c

2017 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

2 RESEARCH APPROACH

We applied a qualitative methodology to investigate

our research question. We conducted a multiple case

study using two out-patient histories in Norway from

September-October 2013. Case study is defined as

“scholarly inquiry that investigates a contemporary

phenomenon within its real-life context (Yin,

1994).” Multiple case study is instrumental study

which allows researchers to understand and analyse

several cases across settings thus leading better

theorising (Stake, 2005; Baxter and Jack, 2008).

Data was collected through conducting

document analysis, observations and interviews at a

surgical out-patient clinic in a hospital in Norway.

Due to ethical consideration, a chief nurse explained

two patients’ histories by showing the electronic

documents in an EHR system and other relevant

paper documents; no direct access to the EHR

system was given to the researcher. Semi-structured

interviews with the chief nurse followed after the

nurse’s explanations. To obtain deeper insight in the

histories, we conducted observations and

unstructured interviews of a secretary working at the

hospital’s post/document centre, a medical doctor

(specialist) and a health secretary working at the

clinic. During the observations, the researcher took

notes and some photos of the documents were taken.

All interviews were audio-recorded. Email

exchanges and telephone conversations

supplemented the data after the interviews.

Document analysis is a systematic method for

reviewing or evaluating documents, which is

unobtrusive and nonreactive when obtaining

empirical data (Bowen, 2009). Observation is a

useful data gathering method in naturally occurring

settings and it helps the researchers to understand

the users’ context, tasks, and goals (Rogers et al.,

2011). Unstructured and semi structured interviews

can be most suitable when the researchers want to

have a deeper insight of a problem domain that is

not familiar by giving the participants the chance to

educate the researchers. (Lazar et al., 2010).

Interviews and/or observation are often used to

establish credibility and minimise bias of the data

from document analysis, as a means of triangulation

(Bowen, 2009). Triangulation is a process of using

several sources of evidence to clarify meaning and

verify the repeatability of an interpretation (Stake,

2005).

We analysed the collected data of two out-patient

histories using qualitative content analysis

(Graneheim and Lundman, 2004). Thematic analysis

(Fereday and Muir-Cochrane, 2006) was used to

fine-tune the analysis.

3 INSIGHT OF THE PATIENT

HISTORIES

In this section, we introduce the patient histories and

explain how we analysed our data. First, we briefly

describe the two out-patient histories. Second, we

present the process of our analysis.

3.1 The Out-patient Histories

The first patient history covered a period of ten and

a half months. Different places were involved in this

case, including a GP centre and two hospitals.

Several stakeholders were involved: a patient, GP,

secretary, radiologist, minimum two specialists,

health secretaries, and nurses from the hospitals.

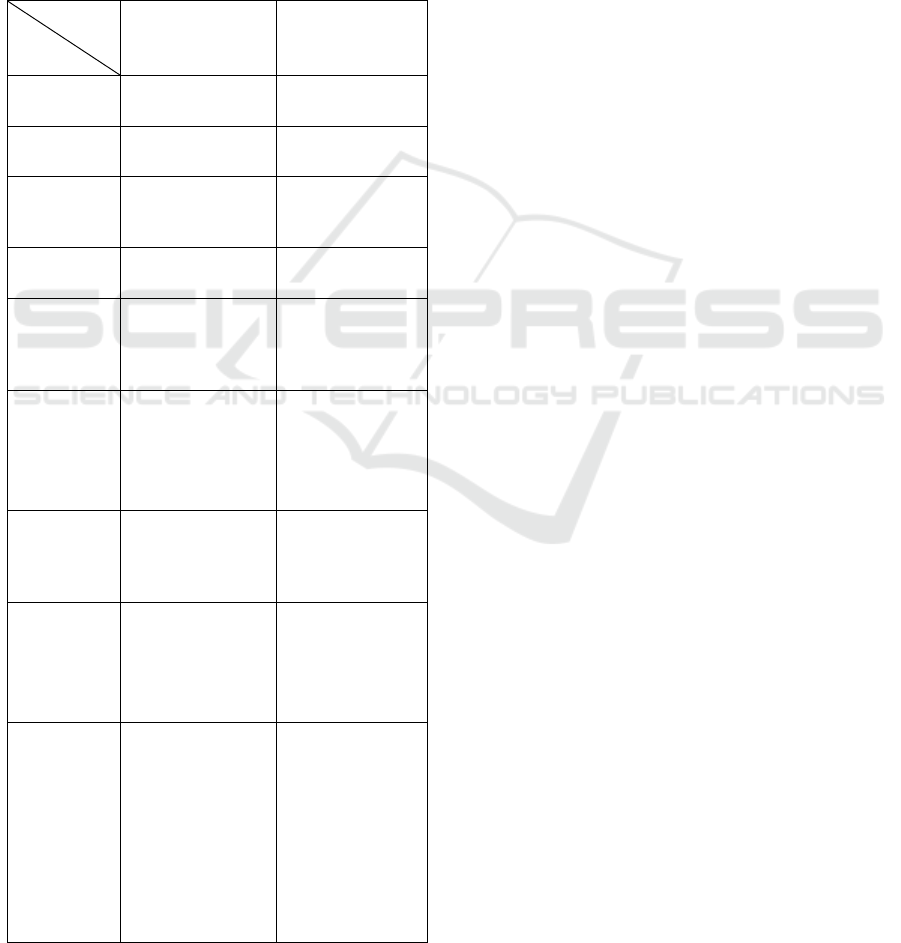

Three different health information systems were

used: a GP’s EHR system, a radiology information

system (RIS), and a hospital EHR system. These

systems were used to store and share the patient

related information. The GP’s EHR system and the

RIS could communicate with the hospital EHR

system in a limited degree (e.g., sending and

receiving electronic referrals or results of computed

tomography (CT)).

The second patient history covered a period of

two and a half months until the time of the interview

and was still ongoing. Different places were

involved in this case, including a GP centre and

three hospitals. Even more stokeholds were

involved: a patient, GP, radiologist, two

pathologists, minimum three specialists, secretaries,

health secretaries, and nurses from the different

hospitals. Four different health information systems

were used: a GP’s EHR system, a RIS, and two

different types of hospital EHR systems. The GP’s

EHR system and the RIS could communicate with a

hospital EHR system in a limited degree, like in the

first case. However, the other hospital EHR system

could not communicate with the three other systems

at all. Therefore, more interactions with physical

evidence, such as a postal letter, were generated to

cover the communication barrier (e.g., a specialist

received a referral via postal letter).

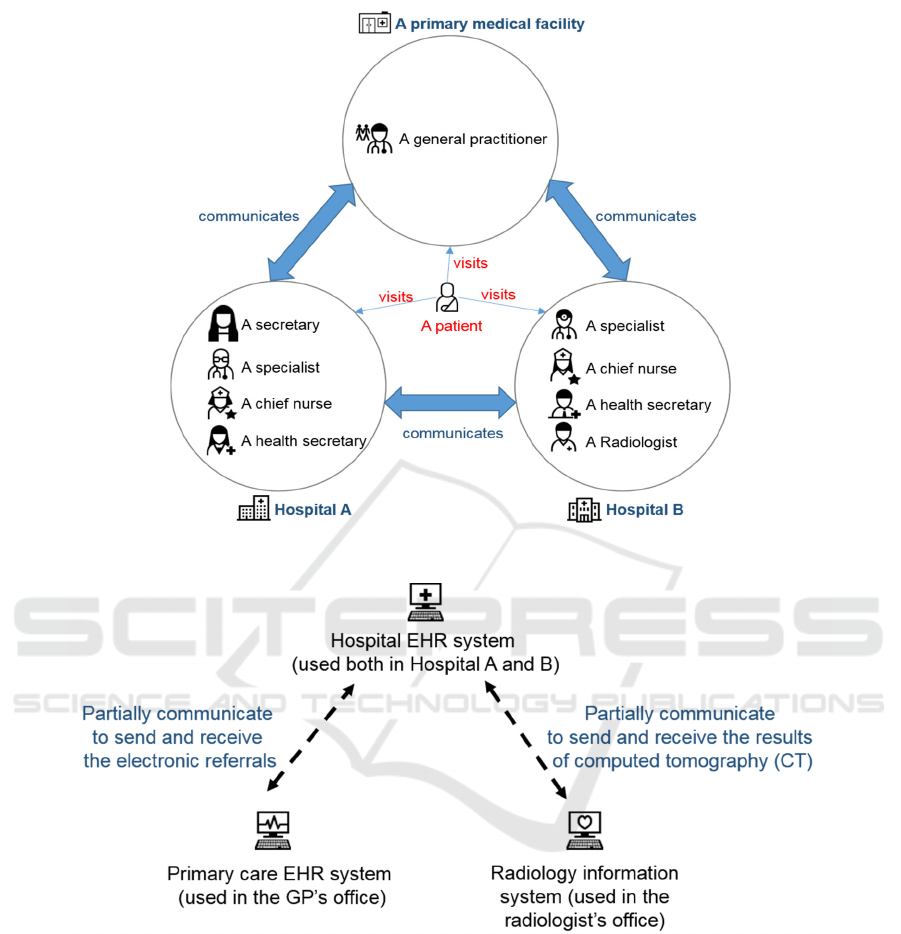

Figure 1 shows the communications between the

stakeholders in the first out-patient case and

Figure 2

shows the communications between the health

information systems in the first out-patient case.

Identifying Key Components of Services in Healthcare in the Context of out-Patient in Norway

355

Figure 1: Communications between the stakeholders in the first out-patient case.

Figure 2: Communications between the health information systems in the first out-patient case.

3.2 Data Analysis Process

Based on the data collected in the researcher’s notes,

audio files, and photos taken, we constructed each

patient’s journey using excel spreadsheet. We

identified key components of services in healthcare

by improving the templates of the journeys in an

iterative manner.

We constructed the first version of the journeys

using a ‘service blueprint (Stickdorn and Schneider,

2010)’ method which includes the roles of the

involved stakeholders, the places where the events

happened, and the contexts of the events. We found

that the stakeholder is either service customer or

worker, and that the place is the service setting. We

learnt the events can be recognised as small units

constituting the entire service provision. Therefore,

we call the context of the event as sub-service

provision context and add it as a key component of

services in healthcare.

We then constructed the second version of the

journeys by improving the first version. While we

HEALTHINF 2017 - 10th International Conference on Health Informatics

356

were doing this, we discovered that some events

contain a sender, a receiver and an object. We also

added the date for each event in the second version.

We learnt that the date can be recognised as an

indicator in the service process.

Finally, we could develop a systematic template

that shows the patients’ journeys (third version). We

added the overall aim of the service and the

identifier for each event. We distinguished the event

involving a sender, receiver and object as a

touchpoint that indicates an interaction between two

stakeholders. We also found that each touchpoint

contains a communication channel that is used in

order to deliver the object to the receiver. We

identified the other events as actions when there is

no such interaction. We discovered that some

touchpoints are electronic-based, occurring in or

between the health information systems. For

example, an electronic referral was sent from a GP’s

EHR system to a Hospital A’s EHR system. We

found that these health information systems can be

seen as stakeholders that contribute to out-patient

services. In addition, we identified various types of

interaction in the patients’ histories: human-to-

human interaction (face-to-face or via telephone),

human-to-physical evidence interaction, and human-

to-computer interaction. We call the aim of the

service as service objective and the type of

interaction as service interaction type and add these

as key components of services in healthcare.

People producing or maintaining an EHR system

have influence on the interactions between a

healthcare professional and the EHR system. We

regard these people as secondary service workers.

A patient can be affected by an interaction between a

healthcare professional and an EHR system. In this

context, we regard the patient as a secondary

service customer.

4 COMPONENTS OF SERVICES

IN HEALTHCARE

In this section, we first present the key components

of services in healthcare, which we identified during

our data analysis. We then present two examples

(one for health service and one for eHealth service)

of the services according to the key components we

analysed from the patient histories.

4.1 Components of Health and eHealth

Services in Out-patient Context

The out-patient histories include interactions situated

in health service and in eHealth service. Here we

define a health service as a conventional medical

service not containing any interactions via electronic

channels. We define an eHealth service as a service

containing interactions via electronic channels. We

identified the key components of health service and

eHealth service separately.

The objective of the interactions situated in the

health services was treatment. Thus, the service

customers were the patients and the secondary

service customers might be family members of the

patients. The service workers were the healthcare

professionals from different groups and

organisations, like a GP and a nurse. The setting of

the interactions situated in the health services were

either a medical facility (e.g., a hospital) or a

location where the patient has a touchpoint (e.g., a

patient reads a postal letter at home or answers a

phonecall at work). The processes of the health

services were sequences of actions and touchpoints

of the patients and the healthcare professionals. We

found that the interaction type situated in the health

services was either human-to-human interaction

(e.g., a GP examines a patient.) or human-to-

physical evidence interaction (e.g., a GP reads a

postal letter from a hospital.). The health services

involved sub-services (smaller units constituting the

service) for the service objective (patient treatment).

The sub-service provision context of the health

services was either a service worker provides a

service to a service customer (e.g., a surgeon

operates on a patient to treat a disease.) or a service

worker provides a service to another service worker

(e.g., a health secretary in a hospital sends an out-

patient note to a GP via postal letter.).

The objective of the interactions situated in the

eHealth services was efficient communication

among healthcare professionals. Therefore, the

service customers were the healthcare professionals

from different groups and organisations, while the

patients became the secondary service customers.

The service workers of the eHealth were the health

information systems such as EHR and RIS, while the

secondary service workers might be people

producing or maintaining the health information

systems. The setting of the interactions situated in

eHealth service was the health information system

software. The processes of the eHealth services were

sequences of touchpoints via the health information

systems. We found that the service interaction type

Identifying Key Components of Services in Healthcare in the Context of out-Patient in Norway

357

situated in the eHealth services was human-to-

computer interaction (e.g., a specialist dictates an

out-patient note through an EHR system). The sub-

service provision context of the eHealth services was

a service worker provides an e-service to a service

customer (e.g., a GP’s EHR system stores a referral,

which can be seen electronically by a secretary in a

hospital’s post centre.)

Table 1 shows the

components we identified as the result of our data

analysis.

Table 1: Components of health and eHealth services in

out-patient context in a hospital in Norway.

Service

type

Component

Health

service

eHealth

service

Service

objective

Treatment

Efficient

communication

Service

customer

Patient

Healthcare

professional

Secondary

service

customer

Family member of

a patient

Patient

Service

worker

Healthcare

professional

Health information

system

Secondary

service

worker

None

People producing

or maintaining the

health information

system

Service

setting

A medical facility

or

a location where a

patient has a

touchpoint

Health information

system software

Service

process

Sequence of actions

and touchpoints of

a patient and health

professionals

Sequence of

touchpoints via

health information

systems

Service

interaction

type

Human to human

or

Human to physical

evidence

interaction

Human to

computer

interaction

Sub-service

provision

context

A service worker

provides

a service to a

service customer

or

A service worker

provides

a service to

a service worker

A service worker

provides an e-

service to a service

customer

4.2 Examples

In this section, we present two examples of the

services according to the key components we

identified. First, we show one example for health

service and then we show one example for eHealth

service.

The following example shows the components

we identified using a part of a hypothetical episode,

in which a patient visits a specialist in a hospital.

Service process: A patient comes to a

specialist’s office room, the specialist talks with

the patient about his/her condition, and then the

specialist examines the patient using a

stethoscope.

Service customer: The patient

Secondary service customer: A spouse of the

patient who accompanies the patient

Service worker: The specialist

Secondary service worker: None

Service setting: An office room for the

specialist at an out-patient clinic in a hospital

Service interaction type: Human to human (the

specialist to the patient) interaction

Sub-service context: A service worker (the

specialist) provides a service (examination with

stethoscope) to a service customer (the patient).

Service objective: Treatment

The following example shows the components

we identified using a part of hypothetical episode

that a specialist writes an out-patient note.

Service process: The specialist navigates to a

dictation module in a desktop-based EHR

system and dictates an out-patient note into the

system.

Service customer: The specialist

Secondary service customer: The patient

Service worker: The EHR system the specialist

uses

Secondary service worker: The people who

produce and maintain the EHR system

Service setting: A desktop-based EHR system

software

Service interaction type: Human to computer

(the specialist to the EHR software) interaction

Sub-service context: A service worker (the

desktop-based EHR system software) provides

an e-service (electronic dictation service) to a

service customer (the specialist).

Service objective: Efficient communication

HEALTHINF 2017 - 10th International Conference on Health Informatics

358

5 DISCUSSION

In this section, we discuss the above-mentioned

results. We especially focus on the additional

components we identified in the out-patient services

during the iterative process of our analysis.

5.1 Service Type: Service vs. e-Service

Characteristics of e-services are different from the

ordinary services since e-services involve

interactions via electronic channels. Väänänen-

Vainio-Mattila et al. (2009) claim that the

characteristics of the service experience

(inseparability, variability, perishability, and

intangibility) are recognised for ordinary services

and do not apply directly to e-services. Therefore,

the components affecting ordinary service and e-

service experience might be different from each

other. We identified components of health service

and eHealth service separately. We found that these

components are not contradictory each other, but

rather complement each other. For example, the

eHealth service in the sub-section 4.2 can be

followed after the health service in the sub-section

4.2 is done. But, it is also possible that an eHealth

service comes before or during a health service. For

example, the specialist can check the patient’s

information via the desktop-based EHR system

software (In other words, the desktop-based EHR

system software provides an electronic patient

information look-up service to the specialist.) before

the patient comes into his/her office. We suggest that

all of the components should be considered when

designing services in healthcare, because today’s

healthcare involves both health service and eHealth

service. Holmlid and Evenson (2008) also argued

that identifying clear genres (in this paper, we call

these service type) and the components offers

efficiency in service design.

5.2 Service Objective

In our case study, the purpose of the health service

was providing treatment to the patients. However, in

the eHealth service perspective, the purpose

becomes efficient communication among healthcare

professionals. Concerning these service objectives, it

might be beneficial to better orchestrate the actions

and touchpoints in service experience when

designing services in healthcare.

5.3 Secondary Service Customer and

Worker

In service dominant logic (Chandler and Vargo,

2011), interactions hidden from customers are not

considered in value co-creation (Wetter-Edman et

al., 2014). However, those interactions can affect the

customers’ service experience. For example, a

patient’s experience can be affected by the

interactions between his/her GP and an EHR system.

Alsos and Svanæs (2011) introduced the concept of

primary and secondary user in eHealth services

context. A primary user indicates a person who uses

an information system directly, and a secondary user

points out a person who relies on the primary user to

get information from the system and who is affected

by the primary user’s experiences with the system

(Alsos and Svanæs, 2011). In the eHealth service

context, the patient becomes a secondary service

customer and people producing/maintaining health

information systems become secondary service

workers. On the other hand, in a health service

context, the family members of a patient become

secondary service customers. Holmlid (2007) argued

that the customer’s customer (secondary service

customer) is as important as the customer in service

design. We postulate that considering not only

secondary service customer, but also secondary

service worker when designing a service, might

contribute to better understanding the whole service

delivery.

5.4 Service Interaction Type

A service consists of different types of interactions.

“The service perspectives become a challenge to

interaction design, and technology usage becomes a

challenge to service design (Holmlid, 2007).”

Paying attention on those types and considering

them in appropriate manners when evaluating and

designing service might be helpful to create

consistency in service provision.

5.5 Sub-Service Provision Context

In a broad and holistic perspective, a service can

contain several sub-services. For instance, an air

travel service consists of sub-services, such as

check-in, providing meal on the plane etc. In

healthcare, many actors are connected to each other

to solve specific tasks and eventually pursuit the

ultimate goal: maximising health of the population

in the society (Coast, 2004). Considering such sub-

service provision types, it would be helpful to better

Identifying Key Components of Services in Healthcare in the Context of out-Patient in Norway

359

coordinate various interactions between different

actors and systems in services in healthcare. In our

case, no ubiquitous computing or pervasive

technology originated sub-service was found.

However, it might appear more and more in future

services as the technology advances. Since the

interactions originated from ubiquitous computing or

pervasive technology happen without the customer’s

direct control (Cellary, 2015), it can be more

challenging for us to well integrate them in service

delivery.

6 LIMITATIONS

There are different types of eHealth service

depending on who communicates with whom. We

conducted our case study with eHealth services

where healthcare professionals communicate with

each other. Thus, the key components in other types

of eHealth service (e.g., telepsychiatry where a

psychiatrist communicates with a patient) might be

different from what we identified.

Our case study was conducted with desktop-based

eHealth services. Conducting a case study with a

mobile-based eHealth service might lead to the

results that are not the same as what we found from

our case study.

7 CONCLUSION

Our research reveals that out-patient care includes

interactions situated in both health service and in

eHealth service. We found that these two different

types of service consist of different components. We

expanded the Fisk et al. (2013)’s four components of

service (service customer, service worker, service

setting, and service process) for services in

healthcare by adding five new components: service

objective, service interaction type, sub-service

provision context, secondary service workers, and

secondary service customer. Considering these

components when evaluating service experience

might support an analytical way of understanding

the complexity in service delivery process in

healthcare. This understanding might contribute to

designing more stakeholder-oriented services in

healthcare.

There is a need for a holistic and stakeholder-

centred approach in designing and evaluating

eHealth services. “the effectiveness of emerging

eHealth technologies in improving the processes or

outcomes of healthcare is unproven (Pagliari,

2007).” We envision further research in the form of

empirical studies that consider the key components

of services in healthcare when evaluating or

designing services in healthcare. Investigating how

to present or document all the actions and

touchpoints of a service delivery process in more

holistic way might also be interesting. Our research

is based on document analysis, observation, and

interview because of the challenges in conducting

ethnography study with patients due to ethical

consideration. Thus, we are also interested in

investigating how to collect richer data that can

provide a deeper insight of services in healthcare.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The research presented here has been conducted

within the VISUAL project (project number 219606)

funded by the Research Council of Norway. Thanks

to Ragnhild Halvorsrud for helping me arranging

data collection activities for the case study, to Maja

Van Der Velden and Stefan Holmlid for guidance in

writing this paper, to our industrial partner for the

contribution. Above all, we thank the participants

who provided data for the case study.

REFERENCES

Alsos, O.A., Svanæs, D., 2011. Designing for the

secondary user experience. In INTERACT 2011, 13th

International Conference on Human-Computer

Interaction. Springer-Verlag. pp. 84–91.

Baxter, P., Jack, S., 2008. Qualitative case study

methodology: Study design and implementation for

novice researchers. The qualitative report 13, 544–

559.

Bowen, G.A., 2009. Document analysis as a qualitative

research method. Qualitative research journal 9, 27–

40.

Cellary, W., 2015. e-Service-dominant Logic. In AHFE

2015, 6th International Conference on Applied Human

Factors and Ergonomics and the Affiliated

Conferences. Procedia Manufacturing. pp. 3629–3635.

Chandler, J.D., Vargo, S.L., 2011. Contextualization and

value-in-context: How context frames exchange.

Marketing Theory 11, 35–49.

Coast, J., 2004. Is economic evaluation in touch with

society’s health values? BMJ 329, 1233–1236.

Fereday, J., Muir-Cochrane, E., 2006. Demonstrating rigor

using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of

inductive and deductive coding and theme

development. International journal of qualitative

methods 5, 80–92.

HEALTHINF 2017 - 10th International Conference on Health Informatics

360

Fisk, R., Grove, S., John, J., 2013. Services Marketing An

Interactive Approach, Cengage Learning. USA, 4th

edition.

Gadrey, J., 2002. The misuse of productivity concepts in

services: Lessons from a comparison between France

and the United States. Edward Elgar Publisher.

Graneheim, U.H., Lundman, B., 2004. Qualitative content

analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and

measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education

Today 24, 105–112.

Hesse, B.W., Shneiderman, B., 2007. eHealth Research

from the User’s Perspective. American Journal of

Preventive Medicine 32, 97–103.

Holmlid, S., 2007. Interaction design and service design:

Expanding a comparison of design disciplines. Nordes

(Nordic Design Research).

Holmlid, S., Evenson, S., 2008. Bringing Service Design

to Service Sciences, Management and Engineering, in:

Hefley, B., Murphy, W. (Eds.), Service Science,

Management and Engineering Education for the 21st

Century, Service Science: Research and Innovations in

the Service Economy. Springer US, pp. 341–345.

Lazar, J., Feng, J.H., Hochheiser, H., 2010. Research

methods in human-computer interaction. Wiley.

Mitchell, J., 2000. Increasing the cost-effectiveness of

telemedicine by embracing e-health. J Telemed

Telecare 6, 16–19.

Pagliari, C., 2007. Design and Evaluation in eHealth:

Challenges and Implications for an Interdisciplinary

Field. J Med Internet Res 9.

Reichert, M., 2011. What BPM Technology Can Do for

Healthcare Process Support, in: Peleg, M., Lavrač, N.,

Combi, C. (Eds.), Artificial Intelligence in Medicine.

Springer Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 2–13.

Rodolfo, I., Laranjo, L., Correia, N., Duarte, C., 2014.

Design Strategy for a National Integrated Personal

Health Record. In NordiCHI ’14, 8th Nordic

Conference on Human-Computer Interaction: Fun,

Fast, Foundational. ACM. pp. 411–420.

Rogers, Y., Sharp, H., Preece, J., 2011. Interaction

Design: Beyond Human Computer Interaction, Wiley.

3rd edition.

Stake, R.E., 2005. Qualitative Case Studies, in: The SAGE

Handbook of Qualitative Research. Sage Publications,

pp. 443–466.

Stickdorn, M., Schneider, J., 2010. This is service design

thinking. Wiley.

Väänänen-Vainio-Mattila, K., Väätäjä, H., Vainio, T.,

2009. Opportunities and Challenges of Designing the

Service User eXperience (SUX) in Web 2.0, in:

Isomäki, H., Saariluoma, P. (Eds.), Future Interaction

Design II. Springer London, pp. 117–139.

Wetter-Edman, K., Sangiorgi, D., Edvardsson, B.,

Holmlid, S., Grönroos, C., Mattelmäki, T., 2014.

Design for Value Co-Creation: Exploring Synergies

between Design for Service and Service Logic.

Service Science 6, 106–121.

Yin, R., 1994. Case study research: Design and methods.

Sage publishing. Beverly Hills. CA,

Identifying Key Components of Services in Healthcare in the Context of out-Patient in Norway

361