Technologies for Ageing in Place to Support Home Monitoring of

Patients with Chronic Diseases

Alexandra Queirós

1

, Luís Pereira

2

, Ana Dias

3

and Nelson Pacheco Rocha

4

1

Health Sciences School, University of Aveiro, Campo Universitário de Santiago, 3810-193 Aveiro, Portugal

2

Medtronic Portugal, Torres de Lisboa, Rua Tomás da Fonseca, Torre E - 11º andar, 1600-209 Lisboa, Portugal

3

Department of Economicas, Management, Industrial Engineering and Tourism, University of Aveiro, Campo

Universitário de Santiago, 3810-193 Aveiro, Portugal

4

Department of Medical Sciences, University of Aveiro, Campo Universitário de Santiago, 3810-193 Aveiro, Portugal

Keywords: Technologies for Ageing in Place, Home Monitoring, Chronic Diseases, Older Adults.

Abstract: Objectives - This study aims to identify: i) the most relevant chronic diseases in terms of the use of

technologies for ageing in place to support home monitoring; and ii) types, outcomes and impacts of

technologies for ageing in place being used to support home monitoring. Methods - A systematic review of

reviews and meta-analysis was performed based on a search of the literature. Results - A total of 35 reviews

and meta-analysis across 4 chronic diseases, diabetes, congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive

pulmonary disease, and hypertension, were retrieved. These studies compare home monitoring supported by

different technologies with usual care. Conclusion - Home monitoring has positive effects in various health

related outcomes, but further research is required to allow its incorporation in the clinical practice.

1 BACKGROUND

The active ageing concept refers not only to the

ability to be physically active or have an occupation,

but also to be able to participate in social, economic,

cultural, civil or spiritual matters (Kickbusch and

Nutbeam, 1998; World Health Organization, 2002).

Therefore, the older adults, even when having some

kind of pathology or disability, should continue to

contribute actively in social terms, together with

their family, friends and community (Kickbusch and

Nutbeam, 1998). In this context, information

technologies have a key role in the promotion of

human functioning and in the mitigation of

limitations, particularly the ones resulting from the

natural ageing process (Queirós, 2013; 2015).

Technological solutions emerge as potentially

cost-effective to meet the needs of citizens and to

promote the services reorganization (Genet et al.,

2011), which are the aims of concepts such as

Medicine 2.0 (Eysenbach, 2008), connected health

(Kvedar, Coye, and Everett, 2014), or holistic health

(Mori et al., 2013; Koch, 2013). In particular,

technologies for ageing in place (Connelly, Mokhtari

and Falk, 2014) can overcome multiple impairments,

including declines in cognitive and functional

abilities (Teixeira et al., 2013; Cruz et al., 2013;

2014) and, consequently, can allow older adults to

live safely, independently, autonomously, and

comfortably, without being required to leave their

own residences, but with the necessary support

services to their changing needs (Pastalan, 1990).

The present study is part of a medium term

project that aims to systematize current evidence of

technologies for ageing in place. Particularly, a

systematic review of reviews and meta-anaysis was

perform to identify technologies being used to

support home monitoring of patients with chronic

diseases, not specifically designed for older adults,

but that can be used by this population, and to

analyse how these tecnologies impact health related

outcomes.

There are several reviews of reviews related to

home care of patients with chronic diseases

(Househ, 2014; McBain, Shipley and Newman,

2015; Kitsiou, Paré and Jaana, 2015; Slev, 2016).

However, these reviews focus on specific

technologies (e.g. short message services (Househ,

2014), or specific pathologies (e.g. congestive heart

failure (Kitsiou, Paré and Jaana, 2015)). Therefore,

the broad analysis of the study reported in the

present article is useful to inform: i) the practitioners

66

Queirøss A., Pereira L., Dias A. and Pacheco Rocha N.

Technologies for Ageing in Place to Support Home Monitoring of Patients with Chronic Diseases.

DOI: 10.5220/0006140000660076

In Proceedings of the 10th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2017), pages 66-76

ISBN: 978-989-758-213-4

Copyright

c

2017 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

about the available home monitoring solutions; and

ii) the researchers about home monitoring issues that

are being object of research.

2 METHODS

Considered the aforementioned objective, the

systematic review of reviews and meta-analysis

reported in the present article was informed by the

following research questions:

What are the most relevant chronic diseases in

terms of the use of technologies for ageing in

place to support home monitoring?

What are the types, outcomes and impacts of

technologies for ageing in place being used to

support home monitoring?

In order to determine the most appropriate search

strategy, an initial scoping study was conducted. The

outcomes of this process were discussed with

various researchers and captured in a review

protocol with explicit descriptions of the methods to

be used and the steps to be taken.

The resources considered to be searched were

two general databases (i.e. Web of Science and

Scopus) and two specific databases (i.e. PubMed, a

medical sciences database, and IEEE Explorer, a

technological database).

The list of keywords for the systematic review

was created through three steps:

First, health related and technological terms

were selected for a draft search strategy based

on the terminology that the authors were

familiar due to their background readings. A

preliminary search with the identified

keywords was tested by two authors.

Afterwards, the two authors carried out a hand

search of the table of contents of three

relevant journals: Journal of Telemedicine and

Telecare, Telemedicine and Ehealth and

Journal of Medical Internet Research.

Finally, new keywords were introduced in

order to gather articles of the mentioned

journals that were not retrieved in the previous

queries.

The queries that resulted from these successive

refinements intended to include: i) all the reviews

where any of the keywords ‘telecare’, ‘telehealth’,

‘telemedicine’, ‘homecare’, ‘telemonitoring’, ‘home

monitoring’, ‘remote monitoring´, ehealth´,

‘telerehabilitation’, ‘mobile health’, ‘mhealth’ or

‘assisted living’ were presented in the title or

abstract; and ii) all the reviews where any the

keywords ‘technology-based’, ‘information

technology’, ‘information and communication’,

‘internet-based’, ‘web-based’, ‘on-line’,

‘smartphones’, ‘mobile apps’, ‘mobile phone’,

‘monitoring devices’ or ‘consumer health

information’ were presented in the title or abstract

together with any of the keywords ‘healthcare’,

‘health care’, ‘patient’, ‘chronic disease’, ‘older’ or

‘elderly’.

The search was limited to articles in English, but

conducted in any country, and performed on 30 of

April of 2016, to include reviews published during

the preceding 10 years.

2.1 Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The study reported in the present article included

reviews and meta-analysis related to technological

solutions that can be used to support home

monitoring of older adults living with a chronic

disease. Chronic disease is defined as an illness that

is prolonged in duration, has a non-self-limited

nature, is rarely cured completely and is associated

with persistent and recurring health problems

(Thrall, 2005; Australian Institute of Health and

Welfare, 2006).

Since the scientific literature presents a large

number of articles that report studies related to home

monitoring, it was planned to include systematic

reviews or meta-analysis only.

The authors excluded all the articles not

published in English or that report systematic

reviews of reviews. Furthermore, the authors also

excluded all the reviews and meta-analysis reporting

solutions that: i) are not focused on the monitoring

of health conditions; ii) target more than one chronic

condition (e.g. diabetes together with congestive

heart failure); iii) target long-term health condition

not related to older patients (e.g. paediatric

conditions); iv) do not target the patients (i.e. studies

that were clinicians focused or were intended

primary to deal with the problems of caregivers

rather than the patients); and v) were designed to be

used in an institutional environment and not in the

domicile of the patients.

2.2 Review Selection

After the removal of duplicates and articles not

published in English, the selection of the remainder

articles was performed by two authors in three steps:

First, the authors assessed all titles for

relevance and those clearly not meeting the

inclusion criteria were removed.

Technologies for Ageing in Place to Support Home Monitoring of Patients with Chronic Diseases

67

Afterwards the abstracts of the retrieved

articles were assessed against the inclusion

and exclusion criteria.

Finally, authors assessed the full text of the

articles according to the outlined inclusion and

exclusion criteria.

In all these three steps any disagreement between

the two authors was discussed and resolved by

consensus.

2.3 Data Extraction

The following characteristics of the retrieved articles

were extracted: i) authors, title and year of

publication; ii) aims of the review or meta-analysis;

iii) target chronic disease; iv) technologies being

used; v) search strategy; vi) inclusion and exclusion

criteria; vii) quality assessment; viii) data extraction

procedure; ix) total number of primary studies; x)

total number of random clinical trials (RCT); xi)

total number of participants; xii) primary outcomes;

xiii) secondary outcomes; xiv) author’s

interpretations; and xv) author’s conclusions.

The relevant data were extracted and recorded

independently by two authors. Once more, any

disagreement between the two authors was discussed

and resolved by consensus.

3 RESULTS

The present study comprises a narrative synthesis of

the retrieved systematic reviews and meta-analyses

and followed the guidelines of the Preferred

Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-

Analyses (PRISMA) (Moher, 2009). Figure 1

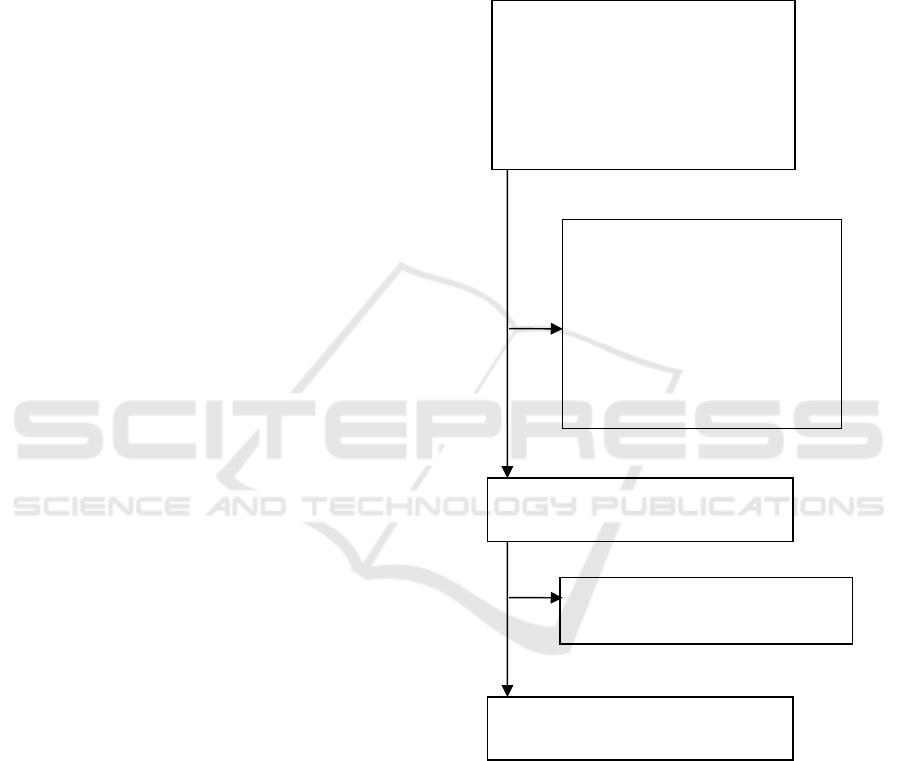

presents the respective flowchart.

A total of 2681 articles were retrieved from the

initial searches on PubMed (822 articles), Web of

Science (1263 articles), Scopus (550 articles) and

IEEE Explorer (46 articles). The initial screening

yielded 1429 articles by removing the duplicates

(1210 articles) or the articles without abstracts or

without the names of the authors (42 articles). After

exclusions based on title alone 563 articles were

retrieved. Additionally, 315 articles were eliminated

based upon review of their abstracts.

The full texts of the 248 remaining articles were

assessed and 213 articles were eliminated, due to the

following reasons: i) the studies target multiple

chronic diseases - 102 articles; ii) the main goals of

the studies are health promotion related to general

population - 48 articles; iii) the studies are not

focused on home monitoring of patients with chronic

diseases - 31 articles; iv) the studies are not

systematic literature reviews or meta-analysis - 12

articles - or are reviews of reviews - 3 articles; v) the

target users are not the patients but the caregivers - 8

articles; vi) the reported solutions are to be used in

an institutional environment or are related to acute

conditions - 4 articles; vi) the studies were not

reported in English - 5 articles.

Figure 1: PRISMA Flowchart.

3.1 Characteristics of the Studies

The 35 resulting articles from the filtered queries

synthesize evidence of home monitoring to support

patients with chronic diseases. After an analysis of

the full text of the retrieved articles, they were

categorized into 4 clinical domains: i) diabetes - 20

articles; ii) congestive heart failure - 9 articles; iii)

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease - 5 articles;

and iv) hypertension - 1 article. The following

Articles found (n=2681):

Web Of Science (n=1263);

Scopus (n=550);

PubMed (n=822);

IEEE Explorer (n=46).

Articles underwent full review (n=248).

Articles excluded by preliminary

screening (n=2079):

Duplicate articles (n=1210);

Articles without abstracts (n=42);

Excluded based on titles (n=512);

Excluded based on abstracts

(n=315).

Excluded based on the full review

(n=213).

Total number of articles (n=35).

HEALTHINF 2017 - 10th International Conference on Health Informatics

68

subsections present the results of these 4 categories.

3.2 Diabetes

Of the 35 retrieved articles, 20 dealt with home

monitoring of patients with diabetes. A significant

number of articles focuses both type 1 and type 2

diabetes (Jaana and Paré, 2007; Verhoeven et al.,

2007; Baron, McBain and Newman, 2012; El-Gayar,

2013; van Vugt et al., 2013; Or and Tao, 2014;

Huang et al., 2015; Tildesley, Po and Ross, 2015;

Riazi et al., 2015; Garabedian, Ross-Degnan and

Wharam, 2015). Others articles focus type 2 diabetes

(Jackson, 2006; Ramadas et al., 2011; Frazetta,

Willet and Fairchild, 2012; Cassimatis and

Kavanagh, 2012; Tao and Or, 2013; Huang et al.,

2015; Hunt, 2015; Ortiz, Felix and Sosa, 2015;

Arambepola, 2016). Only one of the retrieved

studies focuses exclusively on type 1 diabetes

(Peterson, 2014).

By principle, the articles of the diabetes category

include primary studies with high quality scientific

evidence. All the 20 retrieved articles considered

RCT primary studies and 11 of them considered

RCT as one of the inclusion criteria (Jaana and Paré,

2007; Verhoeven et al., 2007; Cassimatis and

Kavanagh, 2012; Baron, McBain and Newman,

2012; Pal et al., 2013; Tao and Or, 2013; van Vugt

et al., 2013; Or and Tao, 2014; Huang et al., 2015;

Tildesley, Po and Ross, 2015; Arambepola, 2016).

On the other hand, aggregating all the primary

studies included in the 20 studies of the diabetes

category it is evident that the number of the involved

patients is relatively significant (e.g. 1 article reports

the involvement of 3578 patients (Pal et al., 2013)

and other reports the involvement of 3798 patients

(Huang et al., 2015)).

In technological terms, several articles (Ramadas

et al., 2011; Frazetta, Willet and Fairchild, 2012; El-

Gayar, 2013; Pal et al.; Tao and Or, 2013; van Vugt

et al., 2013; Huang et al., 2015; Tildesley, Po and

Ross, 2015; Riazi et al., 2015; Hunt, 2015) refer

web-based applications (Table 1). In general, these

applications allow synchronous (e.g. instant

messaging or chat) and asynchronous (e.g. electronic

mail or bulletin board) communications together

with web pages to register clinical parameters (e.g.

weight or blood pressure) and medication.

Besides web-based applications, there are other

technological solutions reported in different articles:

Computer-assisted applications integrating the

management of clinical data with electronic

practice guidelines, reminder systems, and

feedback to the patients (Jackson, 2006; El-

Gayar, 2013).

Smartphones (i.e. standalone smartphones and

smartphones integrating specific devices such

as glucometers for automatic glucose level

upload) (Frazetta, Willet and Fairchild, 2012;

Cassimatis and Kavanagh, 2012; Baron,

McBain and Newman, 2012; El-Gayar, 2013;

Pal et al., 2013; Peterson, 2014; Tildesley, Po

and Ross, 2015; Garabedian, Ross-Degnan

and Wharam, 2015; Hunt, 2015; Ortiz, Felix

and Sosa, 2015; Arambepola, 2016).

Automatic patient data transmission by means

of monitoring devices (i.e. devices to monitor

vital signals or devices to monitor behaviour

outcomes such as pedometers or

accelerometers connected by wireless

communications to monitor physical activity

(Jaana and Paré, 2007)).

Video-conference (Verhoeven et al., 2007; El-

Gayar et al., 2013).

Telephone calls (Riazi et al., 2015).

The main outcome of most of the articles

included in the diabetes category is the control of

glycaemia by using glycosylated haemoglobin

(HbA1c) as a proxy. However, in all the studies, this

aim is complemented with other health related

outcomes (e.g. health related quality of life

(Verhoeven et al., 2007; Ramadas et al., 2011; Pal et

al., 2013; van Vugt et al., 2013), weight (Ramadas et

al., 2011; Pal et al., 2013; Huang et al., 2015;

Garabedian, Ross-Degnan and Wharam, 2015),

depression (Pal et al., 2013), blood pressure

(Verhoeven et al., 2007; Or and Tao, 2014; Riazi et

al., 2015; Garabedian, Ross-Degnan and Wharam,

2015), cholesterol level (Ramadas et al., 2011; Or

and Tao, 2014), triglycemius level (Or and Tao,

2014), fluctuation index (Ramadas et al., 2011)),

behaviour outcomes (e.g. physical activity)

(Jackson, 2006; Verhoeven et al., 2007; Ramadas et

al., 2011; Cassimatis and Kavanagh, 2012; van Vugt

et al., 2013; Riazi et al., 2015; Garabedian, Ross-

Degnan and Wharam, 2015; Hunt, 2015;

Arambepola, 2016), patient self-motivation

(Tildesley, Po and Ross, 2015), patient-clinician

communication (Tildesley, Po and Ross, 2015),

medication adherence (Cassimatis and Kavanagh,

2012; Hunt, 2015) ), and structural outcomes related

to care coordination (Jaana and Paré, 2007;

Verhoeven et al., 2007).

Technologies for Ageing in Place to Support Home Monitoring of Patients with Chronic Diseases

69

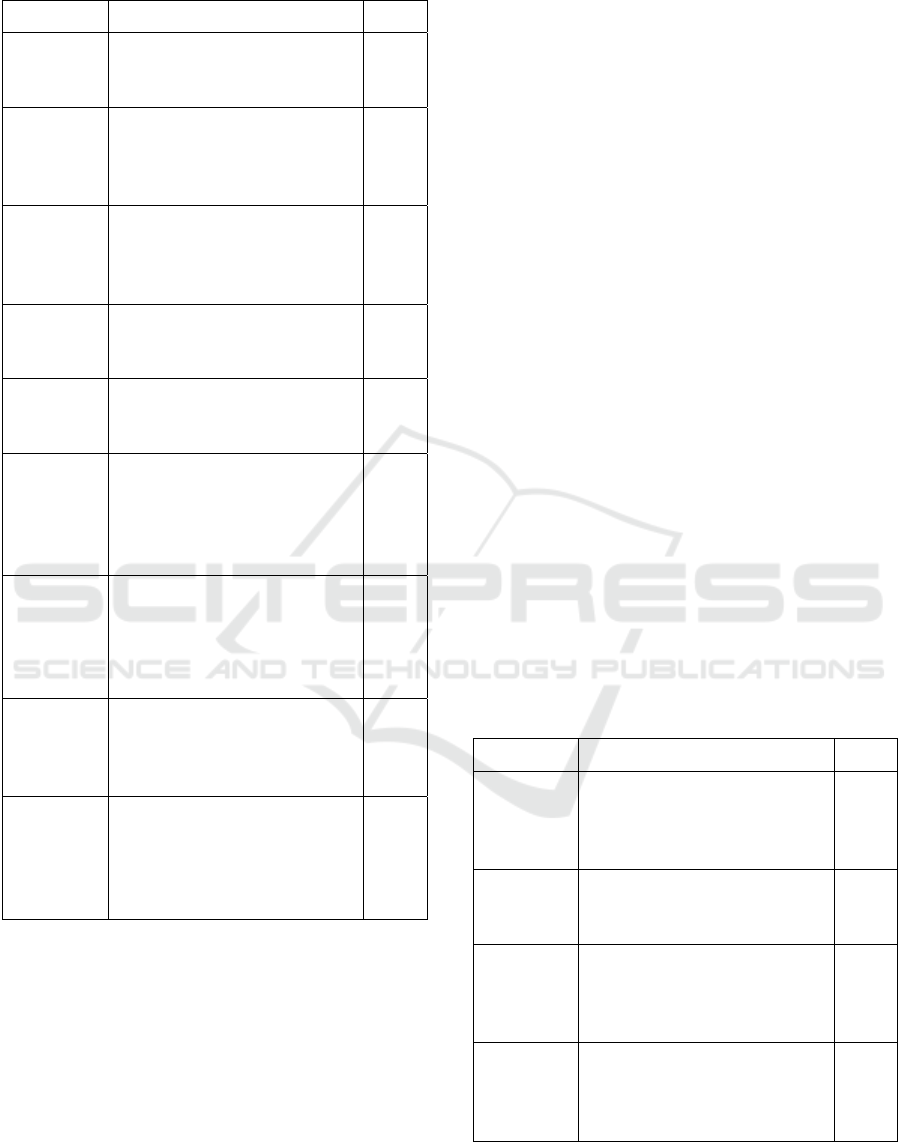

Table 1: Articles that focus diabetes.

Study Technology

(*)

Jackson et

al., 2006

Web-based applications,

computer assisted applications

and standard telephone calls

26/14

Jaana et al.,

2007

Automatic patient data

transmission by means of

monitoring devices

17/17

Verhoeven

et al., 2007

Video-conference 39/39

Ramadas et

al., 2011

Web-based applications 13/8

Frazettaet

al., 2012

Smartphones 7/7

Cassimatis

et al., 2012

Smartphones 13/13

Baron, et

al., 2012

Smartphones 24/24

El-Gayar et

al., 2013

Web-based applications,

smartphones, computer assisted

applications and video-

conference

104/60

Pal et al.,

2013

Web-based applications and

smartphones

16/16

Tao et al.,

2013

Web-based applications 43/43

van Vugt et

al., 2013

Web-based applications 13/13

Or et al.,

2014

Web-based applications 67/67

Peterson Smartphones 14/1

Huang et

al., 2015

Web-based applications and

standard telephone calls

18/18

Tildesley et

al., 2015

Web-based applications and

smartphones

22/22

Riazi et al.,

2015

Web-based applications and

standard telephone calls

67/52

Garabedian

et al., 2015

Smartphones 1479

Hunt, 2015

Web-based applications and

smartphones

14/9

Ortiz et al.,

2015

Smartphones 8/4

Arambepola

et al., 2016

Smartphones 13/13

(*) Number of RCT included in the review / Number of

primary studies include in the review.

Most of the articles of the diabetes category

report moderate to large significant reduction of

HbA1c when compared with usual care (Jackson,

2006; Jaana and Paré, 2007; Frazetta, Willet and

Fairchild, 2012; Cassimatis and Kavanagh, 2012;

Tao and Or, 2013; Or and Tao, 2014; Peterson,

2014; Huang et al., 2015; Tildesley, Po and Ross,

2015; Riazi et al., 2015; Garabedian, Ross-Degnan

and Wharam, 2015; Hunt, 2015; Ortiz, Felix and

Sosa, 2015; Arambepola, 2016). However, several

studies are not conclusive about the reduction of

HbA1c (Verhoeven et al., 2007; Ramadas et al.,

2011; Baron, McBain and Newman, 2012; Pal et al.,

2013). In particular, computer-based diabetes self-

management interventions (Pal et al., 2013) and

consultations supported by video-conference

(Verhoeven et al., 2007) appear to have a small

beneficial effect on glycaemia control.

An article (El-Gayar et al., 2013) reporting

research gaps of the technological approaches

identifies the need to improve the usability of the

applications as well the need for more

comprehensive solutions, including real-time

feedback to the patients and the integration of

electronic health records systems supporting the

service providers.

3.3 Congestive Heart Failure

The number of RCT and non-RCT primary studies

included in the 9 articles dealing with congestive

heart failure varies from 9 to 42 (Table 2). The

majority of the articles (i.e. 6 articles (Chaudhry et

al., 2007; Dang, Dimmick and Kelkar, 2009;

Polisena et al., 2010a; Ciere, Cartwright and

Newman, 2012; Conway, Inglis and Clark, 2014;

Nakamura, Koga and Iseki, 2014)) considered RCT

as one of the inclusion criteria.

Considering the supporting technologies (Table

2), automatic patient data transmission by means of

monitoring devices is being used together with

video-conference and standard telephone calls to

allow the assessment of symptoms and vital signs, as

well as the transmission of automatic alarms.

In terms of clinical outcomes, the main concerns

are the impacts of home monitoring in heart failure-

related hospitalizations and all-cause mortality

(Conway, Inglis and Clark, 2014) when compared

with usual care. However, several secondary

outcomes are also considered such as self-care

behaviour (e.g. adherence to prescribed medication,

daily weighing or adherence to exercise

recommendations (Ciere, Cartwright and Newman,

2012)).

HEALTHINF 2017 - 10th International Conference on Health Informatics

70

Table 2: Articles that focus congestive heart failure.

Study Technology

(*)

Martínez et

al., 2006

Automatic patient data

transmission by means of

monitoring devices

42/13

Chaudhry et

al., 2007

Automatic patient data

transmission by means of

monitoring devices and standard

telephone calls

9/9

Clark et al.,

2007

Automatic patient data

transmission by means of

monitoring devices and standard

telephone calls

14/14

Dang et al.,

2009

Automatic patient data

transmission by means of

monitoring devices

9/9

Polisena et

al., 2010a

Automatic patient data

transmission by means of

monitoring devices

9/9

Ciere et al.,

2012

Automatic patient data

transmission by means of

monitoring devices and standard

telephone calls and video-

conference

12/7

Grustam et

al., 2014

Automatic patient data

transmission by means of

monitoring devices and standard

telephone calls and video-

conference

32/21

Conway et

al.

Automatic patient data

transmission by means of

monitoring devices and standard

telephone calls

25/25

Nakamura

et al., 2014

Automatic patient data

transmission by means of

monitoring devices, including

external, wearable, or

implantable electronic devices

13/13

(*) Number of RCT included in the review / Number of

primary studies include in the review.

Accordingly the reviewed articles home

monitoring has a positive effect on clinical outcomes

in community dwelling patients with congestive

heart failure. Home monitoring reduces mortality

when compared with usual care and it also helps to

lower both the number of hospitalizations and the

use of other health care services (Dang, Dimmick

and Kelkar, 2009; Polisena et al., 2010a; Conway,

Inglis and Clark, 2014; Nakamura, Koga and Iseki,

2014).

However, there is a need for high-quality trials

(Chaudhry et al., 2007). Additionally, Grustam et al.

(2014) state that evidence from the scientific

literature related to home monitoring to support

congestive heart failure patients is still insufficient.

Also, more full economic analyses are needed to

reach a sound conclusion. This means that further

research is required in terms of comparisons of

home monitoring with usual care of patients with

congestive heart failure.

3.4 Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary

Disease

All the retrieved articles dealing with chronic

obstructive pulmonary disease analyse RCT primary

studies (Table 3). In particular, 3 of them considered

RCT as one of the inclusion criteria (Polisena et al.,

2010b; Pedone and Lelli, 2015; Lundell et al., 2015).

Home monitoring is supported by commercially

available devices to measure and transmit different

types of information (e.g. weight, temperature, blood

pressure, oxygen saturation, spirometry parameters,

symptoms, medication usage or steps in 6-minutes

walking distance). In some cases the automatic data

acquisition is complemented by clinical staff using

questionnaires in telephone interviews (Polisena et

al., 2010b; Pedone and Lelli, 2015). Video-

conference can also be used to provide feedback to

the patients (Lundell et al., 2015).

Table 3: Articles that focus chronic obstructive pulmonary

disease.

Study Technology

(*)

Polisena et

al., 2010b

Automatic patient data

transmission by means of

monitoring devices and standard

telephone calls

10/10

Bolton et al.

2011

Automatic patient data

transmission by means of

monitoring devices

6/2

Pedone et

al., 2015

Automatic patient data

transmission by means of

monitoring devices and standard

telephone calls

12/12

Lundell et

al., 2015

Automatic patient data

transmission by means of

monitoring devices and video-

conference

9/9

(*) Number of RCT included in the review / Number of

primary studies include in the review.

Technologies for Ageing in Place to Support Home Monitoring of Patients with Chronic Diseases

71

In what concerns the primary and secondary

outcomes, 3 studies (Polisena et al., 2010b; Bolton et

al. 2011; Pedone and Lelli, 2015) compare home

monitoring with usual care of patients with chronic

obstructive pulmonary disease, considering

mortality, admissions to hospital or other health care

utilization as primary outcomes. Secondary

outcomes include, among others, health related

quality of life, patient satisfaction, physical capacity

and dyspnea.

Home monitoring was found to reduce rates of

hospitalization and emergency department visits,

while the findings related to hospital bed days of

care varied between studies (Polisena et al., 2010b;

Pedone and Lelli, 2015). However, 1 study (Polisena

et al., 2010b) reports a greater mortality in a

telephone-support group compared with usual care.

Additionally, there is evidence that home monitoring

has a positive effect on physical capacity and

dyspnea (Lundell et al., 2015) and it is similar or

better than usual care in terms of quality of life and

patient satisfaction outcomes (Polisena et al.,

2010b).

The evidence systematized by the articles of the

category related to chronic obstructive pulmonary

disease does not allow drawing definite conclusions,

as the studies are small. The benefit of home

monitoring of patients with chronic obstructive

pulmonary disease is not yet proven and further

research is required before wide-scale

implementation be supported.

3.5 Hypertension

Finally, concerning patients with hypertension 1

article systematizes the results of 12 RCT using

devices with automated data transmission, and

video-conference.

The article reports improvements in the

proportion of participants with controlled blood

pressure compared to those who received usual care,

but the authors conclude that more interventions are

required and cost-effectiveness of the intervention

should also be assessed (Chandak and Joshi, 2015).

4 DISCUSSION

According to the findings of the systematic review

reported in the present article, diabetes, congestive

heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

and hypertension are the most relevant chronic

diseases in terms of the use of technologies for

ageing in place to support home monitoring (i.e. the

first research question of the present study).

Type 1 and type 2 diabetes stand out from other

chronic conditions with a total of 20 studies, which

constitute 57.1% of the articles that were retrieved.

In order of relevance, the second chronic condition

is congestive heart failure (i.e. 28.6% of the articles

that were retrieved), which was followed by chronic

obstructive pulmonary disease (i.e. 11.4% of the

articles that were retrieved). Furthermore, one article

reporting a systematic review related to home

monitoring of patients with hypertension was also

included in the present systematic review.

Self-management of diabetes requires patient

adherence to best practice recommendations (e.g.

glucose monitoring, dietary management or physical

activity) (Or and Tao, 2014), congestive heart failure

has a high rate of hospital readmission (Bonow,

2005; Joe and Demiris, 2013) and key aspects of the

natural history of the chronic obstructive pulmonary

disease are episodes of acute exacerbations, which

are considered related to a faster disease

progression, presence of comorbidities, and worse

functional prognosis (Calvo, 2014). Therefore, the

results of the present systematic review are in line

with the current strong motivation for using

technological solutions as a way to monitor patients

with chronic diseases at home and to promote an

increasing compliance of self-care.

In terms of types, outcomes, and impacts of

technologies supporting home monitoring of patients

with chronic diseases (i.e. the second research

question of the study reported in the present article),

the results show that:

The technological solutions being used

include web-based applications, computer

assisted applications, smartphones, automatic

patient data transmission by means of

monitoring devices, video-conference and

standard telephone calls (Tables 1-3).

In general, the systematic reviews compare

home monitoring with usual care and the

primary outcomes depend of the type of the

patients being considered (e.g. glycaemia

control for patients with diabetes, patient’s

readmissions and mortality for patients with

congestive heart failure and patients with

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or

control of the blood pressure of patients with

hypertension).

Secondary outcomes are quite diverse and

include health related quality of life, weight,

depression, blood pressure, behaviour

outcomes, self-management, care knowledge,

medication adherence, patient-clinician

HEALTHINF 2017 - 10th International Conference on Health Informatics

72

communication, or structural outcomes related

to care coordination.

The analysis of the retrieved articles suggest

that home monitoring has positive effects with

a moderate to large improvements of different

outcomes when compared with usual care of

patients with diabetes, congestive heart

failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

and hypertension (although in this case the

evidence is not as robust – only 1 article – as it

is in the other 3 chronic diseases). However,

some studies are not conclusive about this

positive impact and only report small

beneficial effects.

Despite a high level of technological innovation

and implementation, one of the findings is that

telephone calls are still an important channel for the

communication between patients and care providers.

Furthermore, it seems that important aspects are

neglected during the technological developments,

since there are reports of usability drawbacks as well

as reports of the need for more comprehensive

solutions, including provision of real-time feedback

and the integration of the electronic health records

systems being used by the care providers (El-Gayar

et al., 2013).

Therefore, the results show that not only

disruptive technological solutions have a key role

when dealing with home monitoring, since practical

and robust solutions are required, which means that

the integration and the interoperability of existing

technologies assume a great importance.

In general, the retrieved studies suggest positive

effects of home monitoring, but evidence provided

for the real benefit of home monitoring in some

aspects was not totally convincing. Further research,

including large scale RCT trials with consistent

primary and secondary outcomes, and robust

analysis about long-term sustainability, is required to

allow the full incorporation of home monitoring in

the clinical practice.

5 CONCLUSION

Considering the large amount of articles that report

studies related to home monitoring of patients with

chronic diseases, the authors decided to perform a

review of reviews and meta-analysis.

Although the authors tried to be as elaborate as

possible in methodological terms to guarantee that

the review selection and the data extraction were

rigorous, it should be acknowledged that this study

has limitations, namely the weaknesses inherent to

secondary analyses (i.e. review of reviews and meta-

analysis), the limitations related to the dependency

on the keywords and the databases selected, or the

assumption that the retrieved articles have a

homogeneous quality, which was not verified.

Despite these possible biases, the authors believe

that the systematically collected evidence

contributes to the understanding of the use of

technologies for ageing in place to support home

monitoring of patients with chronic diseases.

In parallel with this study, the authors have used

similar methods to analyse the role of technologies

for ageing in place to empower patients with chronic

diseases. However, due to several limitations, the

authors decide not to report the results in this article.

Therefore, these results will be the object of a future

publication. Also, as a future work, further studies

will be implemented, namely to analyse how

technologies for ageing in place are being used to

support daily activities and promote the participation

in social, economic, cultural, civil or spiritual

matters of older adults.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was partially supported by COMPETE -

Programa Operacional Competitividade e

Internacionalização (COMPETE 2020), Sistema de

Incentivos à Investigação e Desenvolvimento

Tecnológico (SI I&DT), under the project Social

Cooperation for Integrated Assisted Living

(SOCIAL).

REFERENCES

Arambepola, C., Ricci-Cabello, I., Manikavasagam, P.,

Roberts, N., French, D.P. and Farmer, A., 2016. The

impact of automated brief messages promoting

lifestyle changes delivered via mobile devices to

people with type 2 diabetes: a systematic literature

review and meta-analysis of controlled trials. Journal

of medical Internet research, 18(4).

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2006. Chronic

Diseases and Associated Risk Factors in Australia,

2006. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

Baron, J., McBain, H. and Newman, S., 2012. The impact

of mobile monitoring technologies on glycosylated

hemoglobin in diabetes: a systematic review. Journal

of diabetes science and technology, 6(5), pp.1185-

1196.

Bolton, C.E., Waters, C.S., Peirce, S. and Elwyn, G.,

2011. Insufficient evidence of benefit: a systematic

Technologies for Ageing in Place to Support Home Monitoring of Patients with Chronic Diseases

73

review of home telemonitoring for COPD. Journal of

evaluation in clinical practice, 17(6), pp.1216-1222.

Bonow, R.O., Bennett, S., Casey, D.E., Ganiats, T.G.,

Hlatky, M.A., Konstam, M.A., Lambrew, C.T.,

Normand, S.L.T., Pina, I.L., Radford, M.J. and Smith,

A.L., 2005. ACC/AHA clinical performance measures

for adults with chronic heart failure: a report of the

American College of Cardiology/American Heart

Association task force on performance measures

(writing committee to develop heart failure clinical

performance measures) endorsed by the Heart Failure

Society of America. Journal of the American College

of Cardiology, 46(6), pp.1144-1178.

Calvo, G.S., Gómez-Suárez, C., Soriano, J.B., Zamora, E.,

Gónzalez-Gamarra, A., González-Béjar, M., Jordán,

A., Tadeo, E., Sebastián, A., Fernández, G. and

Ancochea, J., 2014. A home telehealth program for

patients with severe COPD: the PROMETE study.

Respiratory medicine, 108(3), pp.453-462.

Cassimatis, M. and Kavanagh, D.J., 2012. Effects of type

2 diabetes behavioural telehealth interventions on

glycaemic control and adherence: a systematic review.

Journal of telemedicine and telecare, 18(8), pp.447-

450.

Chandak, A. and Joshi, A., 2015. Self-management of

hypertension using technology enabled interventions

in primary care settings. Technology and Health Care,

23(2), pp.119-128.

Chaudhry, S.I., Phillips, C.O., Stewart, S.S., Riegel, B.,

Mattera, J.A., Jerant, A.F. and Krumholz, H.M., 2007.

Telemonitoring for patients with chronic heart failure:

a systematic review. Journal of cardiac failure, 13(1),

pp.56-62.

Ciere, Y., Cartwright, M. and Newman, S.P., 2012. A

systematic review of the mediating role of knowledge,

self-efficacy and self-care behaviour in telehealth

patients with heart failure. Journal of telemedicine and

telecare, 18(7), pp.384-391.

Clark, R.A., Inglis, S.C., McAlister, F.A., Cleland, J.G.

and Stewart, S., 2007. Telemonitoring or structured

telephone support programmes for patients with

chronic heart failure: systematic review and meta-

analysis. Bmj, 334(7600), p.942.

Connelly, K., Mokhtari, M. and Falk, T.H., 2014.

Approaches to Understanding the impact of

technologies for aging in place: a mini-review.

Gerontology, 60(3), pp.282-288.

Conway, A., Inglis, S.C. and Clark, R.A., 2014. Effective

technologies for noninvasive remote monitoring in

heart failure. Telemedicine and e-Health, 20(6),

pp.531-538.

Cruz, V.T., Pais, J., Bento, V., Mateus, C., Colunas, M.,

Alves, I., Coutinho, P. and Rocha, N.P., 2013. A

rehabilitation tool designed for intensive web-based

cognitive training: Description and usability study.

Journal of Medical Internet Research, 15 (12), p. e59.

Doi: 10.2196/resprot.2899.

Cruz, V.T., Pais, J., Alves, I., Ruano, L., Mateus, C.,

Barreto, R., Bento, V., Colunas, M., Rocha, N. and

Coutinho, P., 2014. Web-based cognitive training:

patient adherence and intensity of treatment in an

outpatient memory clinic. Journal of medical Internet

research, 16(5), p. e122. Doi: 10.2196/jmir.3377.

Dang, S., Dimmick, S. and Kelkar, G., 2009. Evaluating

the evidence base for the use of home telehealth

remote monitoring in elderly with heart failure.

Telemedicine and e-Health, 15(8), pp.783-796.

El-Gayar, O., Timsina, P., Nawar, N. and Eid, W., 2013. A

systematic review of IT for diabetes self-management:

are we there yet?. International journal of medical

informatics, 82(8), pp.637-652.

Eysenbach, G., 2008. Medicine 2.0: social networking,

collaboration, participation, apomediation, and

openness. Journal of medical Internet research, 10(3),

p.e22.

Frazetta, D., Willet, K. and Fairchild, R., 2012. A

systematic review of smartphone application use for

type 2 diabetic patients. Online Journal of Nursing

Informatics (OJNI), 16(3).

Garabedian, L.F., Ross-Degnan, D. and Wharam, J.F.,

2015. Mobile phone and smartphone technologies for

diabetes care and self-management. Current diabetes

reports, 15(12), pp.1-9.

Genet, N., Boerma, W.G., Kringos, D.S., Bouman, A.,

Francke, A.L., Fagerström, C., Melchiorre, M.G.,

Greco, C. and Devillé, W., 2011. Home care in

Europe: a systematic literature review. BMC health

services research, 11(1), p.1.

Grustam, A.S., Severens, J.L., van Nijnatten, J., Koymans,

R. and Vrijhoef, H.J., 2014. Cost-effectiveness of

telehealth interventions for chronic heart failure

patients: a literature review. International journal of

technology assessment in health care, 30(01), pp.59-

68.

Househ, M., 2014. The role of short messaging service in

supporting the delivery of healthcare: An umbrella

systematic review. Health informatics journal,

p.1460458214540908.

Huang, Z., Tao, H., Meng, Q. and Jing, L., 2015.

MANAGEMENT OF ENDOCRINE DISEASE:

Effects of telecare intervention on glycemic control in

type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis

of randomized controlled trials. European Journal of

Endocrinology, 172(3), pp.R93-R101.

Hunt, C.W., 2015. Technology and diabetes self-

management: An integrative review. World journal of

diabetes, 6(2), pp.225-233.

Jaana, M. and Paré, G., 2007. Home telemonitoring of

patients with diabetes: a systematic assessment of

observed effects. Journal of evaluation in clinical

practice, 13(2), pp.242-253.

Jackson, C.L., Bolen, S., Brancati, F.L., Batts?Turner,

M.L. and Gary, T.L., 2006. A systematic review of

interactive computer?assisted technology in diabetes

care. Journal of general internal medicine, 21(2),

pp.105-

Joe, J. and Demiris, G., 2013. Older adults and mobile

phones for health: A review. Journal of biomedical

informatics, 46(5), pp.947-954.

HEALTHINF 2017 - 10th International Conference on Health Informatics

74

Kickbusch, I. and Nutbeam, D., 1998. Health promotion

glossary. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Kitsiou, S., Paré, G. and Jaana, M., 2015. Effects of home

telemonitoring interventions on patients with chronic

heart failure: an overview of systematic reviews.

Journal of medical Internet research, 17(3), p.e63.

Koch, S., 2013. Achieving holistic health for the

individual through person-centered collaborative care

supported by informatics. Healthcare informatics

research, 19(1), pp.3-8.

Kvedar, J., Coye, M.J. and Everett, W., 2014. Connected

health: a review of technologies and strategies to

improve patient care with telemedicine and telehealth.

Health Affairs, 33(2), pp.194-199.

Lundell, S., Holmner, Å., Rehn, B., Nyberg, A. and

Wadell, K., 2015. Telehealthcare in COPD: a

systematic review and meta-analysis on physical

outcomes and dyspnea. Respiratory medicine, 109(1),

pp.11-26.

Martínez, A., Everss, E., Rojo-Álvarez, J.L., Figal, D.P.

and García-Alberola, A., 2006. A systematic review of

the literature on home monitoring for patients with

heart failure. Journal of telemedicine and telecare,

12(5), pp.234-241.

McBain, H., Shipley, M. and Newman, S., 2015. The

impact of self-monitoring in chronic illness on

healthcare utilisation: a systematic review of reviews.

BMC health services research, 15(1), p.1.

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J. and Altman, D.G.,

2009. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews

and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Annals of

internal medicine, 151(4), pp.264-269.

Mori, A.R., Mazzeo, M., Mercurio, G. and Verbicaro, R.,

2013. Holistic health: predicting our data future (from

inter-operability among systems to co-operability

among people). International journal of medical

informatics, 82(4), pp.e14-e28.

Nakamura, N., Koga, T. and Iseki, H., 2014. A meta-

analysis of remote patient monitoring for chronic heart

failure patients. Journal of telemedicine and telecare,

20(1), pp.11-17.

Or, C.K. and Tao, D., 2014. Does the use of consumer

health information technology improve outcomes in

the patient self-management of diabetes? A meta-

analysis and narrative review of randomized controlled

trials. International journal of medical informatics,

83(5), pp.320-329.

Ortiz, P.M.V., Felix, P.M. and Sosa, E.S.G., 2015. Text

messaging interventions to glycemic control in type 2

diabetes adults: systematic review/Mensajes de texto

para el control glucémico en adultos con diabetes tipo

2: revisión sistemática. Enfermería Global, 14(1),

p.445.

Pal, K., Eastwood, S.V., Michie, S., Farmer, A.J., Barnard,

M.L., Peacock, R., Wood, B., Inniss, J.D. and Murray,

E., 2013. Computerbased diabetes selfmanagement

interventions for adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus.

The Cochrane Library.

Pastalan, L.A., 1990. Aging in place: The role of housing

and social supports (Vol. 6, No. 1-2). Psychology

Press.

Pedone, C. and Lelli, D., 2015. Systematic review of

telemonitoring in COPD: an update. Pneumonol

Alergol Pol, 83, pp.476-8484.

Peterson, A. (2014). Improving Type 1 Diabetes

Management With Mobile Tools A Systematic

Review. Journal of diabetes science and technology,

8(4), 859-864.

Polisena, J., Tran, K., Cimon, K., Hutton, B., McGill, S.,

Palmer, K. and Scott, R.E., 2010. Home

telemonitoring for congestive heart failure: a

systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of

Telemedicine and Telecare, 16(2), pp.68-76.

Polisena, J., Tran, K., Cimon, K., Hutton, B., McGill, S.,

Palmer, K. and Scott, R.E., 2010. Home telehealth for

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic

review and meta-analysis. Journal of telemedicine and

telecare, 16(3), pp.120-127.

Queirós, A., Carvalho, S., Pavão, J. and da Rocha, N.P.,

2013. AAL Information based Services and Care

Integration. In HEALTHINF 2013 - Proceedings of

the International Conference on Health Informatics,

pp. 403-406.

Queirós, A., Silva, A., Alvarelhão, J., Rocha, N.P. and

Teixeira, A., 2015. Usability, accessibility and

ambient-assisted living: a systematic literature review.

Universal Access in the Information Society, 14(1),

pp.57-66. Doi: 10.1007/s10209-013-0328-x.

Ramadas, A., Quek, K.F., Chan, C.K.Y. and Oldenburg,

B., 2011. Web-based interventions for the

management of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic

review of recent evidence. International Journal of

Medical Informatics, 80(6), pp.389-405.

Riazi, H., Larijani, B., Langarizadeh, M. and Shahmoradi,

L., 2015. Managing diabetes mellitus using

information technology: a systematic review. Journal

of Diabetes & Metabolic Disorders, 14(1), p.1.

Slev, V.N., Mistiaen, P., Pasman, H.R.W., Verdonck-de

Leeuw, I.M., van Uden-Kraan, C.F. and Francke, A.L.,

2016. Effects of eHealth for patients and informal

caregivers confronted with cancer: A meta-review.

International journal of medical informatics, 87,

pp.54-67.

Tao, D. and Or, C.K., 2013. Effects of self-management

health information technology on glycaemic control

for patients with diabetes: a meta-analysis of

randomized controlled trials. Journal of telemedicine

and telecare, 19(3), pp.133-143.

Teixeira, A., Pereira, C., e Silva, M.O., Alvarelhão, J.,

Silva, A.G., Cerqueira, M., Martins, A.I., Pacheco, O.,

Almeida, N., Oliveira, C. and Costa, R., 2013. New

telerehabilitation services for the elderly. I. Miranda,

M. Cruz-Cunha, Handbook of Research on ICTs and

Management Systems for Improving Efficiency in

Healthcare and Social Care, IGI Global, pp.109-132.

Doi: 10.4018/978-1-4666-3990-4.ch006.

Thrall, J.H., 2005. Prevalence and Costs of Chronic

Disease in a Health Care System Structured for

Technologies for Ageing in Place to Support Home Monitoring of Patients with Chronic Diseases

75

Treatment of Acute Illness 1. Radiology, 235(1), pp.9-

12.

Tildesley, H.D., Po, M.D. and Ross, S.A., 2015. Internet

Blood Glucose Monitoring Systems Provide Lasting

Glycemic Benefit in Type 1 and 2 Diabetes: A

Systematic Review. Medical Clinics of North

America, 99(1), pp.17-33.

van Vugt, M., de Wit, M., Cleijne, W.H. and Snoek, F.J.,

2013. Use of behavioral change techniques in web-

based self-management programs for type 2 diabetes

patients: systematic review. Journal of medical

Internet research, 15(12), p.e279.

Verhoeven, F., van Gemert-Pijnen, L., Dijkstra, K.,

Nijland, N., Seydel, E. and Steehouder, M., 2007. The

contribution of teleconsultation and videoconferencing

to diabetes care: a systematic literature review. J Med

Internet Res, 9(5), p.e37.

World Health Organization, 2002. Active ageing: a policy

framework: a contribution of the World Health

Organization to the Second United Nations World

Assembly on Ageing. Madrid (ES): World Health

Organization.

HEALTHINF 2017 - 10th International Conference on Health Informatics

76