Culture Contextualization in Open e-Learning Systems

Improving the Re-use of Open Knowledge Resources by Adaptive Contextualization

Processes

J. Stoffregen and J. Pawlowski

Dept. of Computer Science and Information Systems, University of Jyväskylä, P.O. Box 35, FI-40014, Jyväskylä, Finland

Keywords: Open e-Learning, Public Administration, Open Knowledge Resources, Adaptive Contextualization.

Abstract: The paper provides a contextualization process to adapt Open Knowledge Resources for the need of public

administrations. By help of a matching strategy, culture and context profiles of learners and learning

resources are compared. The comparison allows to draw inferences how to contextualize an open know-

ledge resource for own learning needs. An example is illustrated and future research fields are proposed.

1 INTRODUCTION

Local Public administrations are facing pressure to

innovate services and processes to become more

open, transparent and efficient for the public good.

Similarly, the increasing digitization of

administrative processes requires public employees

to advance their competences and keep up with

change. They have to acquire knowledge quickly

and apply it to everyday routines.

To improve flexibility in training and knowledge

exchange, public administrations are about to

explore the use of e-Learning systems and open

knowledge resources at the workplace. Despite that

learning materials are available, considerable

challenges inhibit the effective use of open e-

Learning systems in the public sector.

Among the challenges is the difficulty to decide:

how to adapt a resource for personal learning

means? The following position paper contributes to

answer this question. While it may be intuitive to

decide whether or not to translate the language of a

text, it is more difficult with regard to embodied

cultural and context factors such as basic

assumptions about discussion at the workplace, for

example. Different strategies need to be embarked to

facilitate the re-use of open knowledge resources for

personal learning means.

The following paper will present a

contextualization model which maps adaptation

strategies to salient culture- and context factors of

learners in public administration contexts. The

model is adaptive given that it recommends

strategies based on a given learner and resource

profile. The paper will proceed as follows:

In chapter 2, background work about

contextualization processes in e-Learning will be

summarized. In chapter 3 the design science

approach to build the contextualization model will

be outlined. Based on that, the contextualization

model is presented and discussed in chapter 4.

2 BACKGROUND LITERATURE

Chapter two will provide background knowledge on

culture and context factors. Subsequently, current

approaches to contextualization of e-Learning and

use of Open Knowledge Resources (OKR) will be

addressed.

2.1 Culture and Context Factors in

Public Administrations

Culture and context of public administrations is

often summarized under the buzzword bureaucracy

or red tape. This simplified view, however, does not

help to qualify basic assumptions, convictions,

behaviour and artefacts (Schein, 2010) that represent

the way of being and rationalizing of public

employees. Yet, only few studies elaborate factors in

public sector shaping the use of open e-Learning

systems. Eidson (2009), Chen (2014) and Bimrose et

al., (2014) have elaborated on barriers and

Stoffregen, J. and Pawlowski, J.

Culture Contextualization in Open e-Learning Systems - Improving the Re-use of Open Knowledge Resources by Adaptive Contextualization Processes.

DOI: 10.5220/0005842707670774

In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Model-Driven Engineering and Software Development (MODELSWARD 2016), pages 767-774

ISBN: 978-989-758-168-7

Copyright

c

2016 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

767

assumptions shaping e-Learning effectiveness.

Among these is the time available for learning,

available resources, support and perceived ease of

use. Conradie and Choenni (2012) have elaborated

on processes of information release and stated that

fear of false conclusions, financial concerns, role of

ownership of data are barriers. Further threshold is

the lack of legal frameworks, decentralized data

storage and low priority of processes at the

workplace.

So far, the studies focus either on the opening of

data and information or e-Learning activities. Open

e-Learning systems, however, make public

employees to creators by generating and re-using

open knowledge resources for own learning means.

Recently, a culture model dedicated to open e-

Learning in public sectors has been advanced

(Stoffregen et al., forthcoming). Following an expert

validation, the following nine factors and

assumptions can be posed.

One set of factors is associated to the internal

group system, such as openness in discourse.

Depending on assumptions whether or not to

innovate routines and discussing errors at the job

place, public employees will decide to involve in

OKR exchange. Another factor is group

identification. Depending on the match of work

domains, geography and language (terminology), the

exchange of OKR will succeed. Learning at the

workplace is another factor. Depending on

assumptions about responsibilities to choose

learning resources for adaptation, OKR are used.

Another factor is the perceived superior support. If

superiors do not support public employees actively

and by symbolic support, the exchange of OKR will

remain on a low level.

Coming to technology structures, one culture

factor is the spirit of open e-Learning platforms. If

public employees perceive the platform as a

monitoring tool for superiors, the engagement will

be low. Another factor is the format of media. Both

the content (abstract / applied) and accommodated

diversity of an OKR to match assumptions of public

employees to facilitate re-use and adaptation.

Concerning factors in the organizational

environment, a first one is regulation. While it is

not essential where rules are located they have to be

provided to empower employees, to tell how to

perform adaptation and exchange. Last but not least,

environmental artefacts such as internet

infrastructure and tools to engage in the adaption of

OKR have to be provided.

The model provides a comprehensive overview

of culture and context factors shaping activities in

open e-Learning systems. For developing a culture

contextualization model for the public sector, the

factors mentioned will be taken into account. In the

following, the design science method for developing

the culture contextualization model is provided.

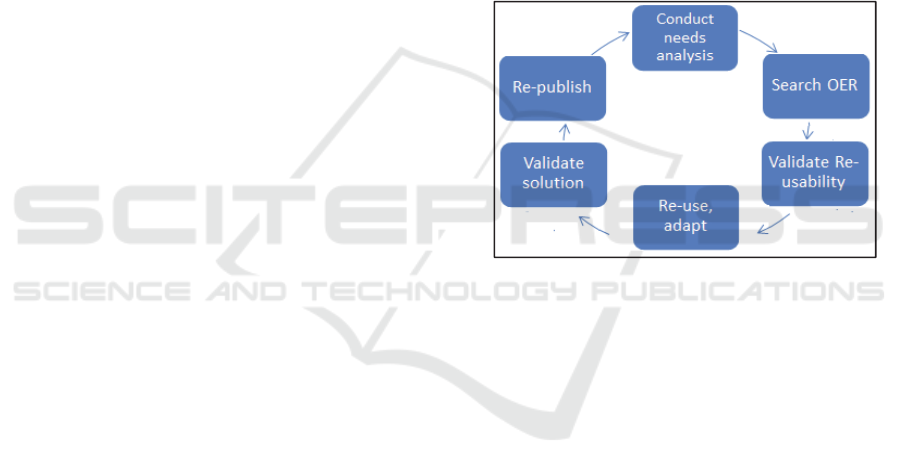

2.2 Contextualization Processes

Culture contextualization can be described as a

cyclical process as depictured in Figure 1. It begins

with a needs analysis (what is to learn and what

culture factors are at stake), the search of open

knowledge resources (OKR), validation of the

OKR’s re-usability, use / adaptation of OKR and re-

publishing of OKR and experiences (cf.

Mikroyannidis et al., 2010; Dunn and Marinetti,

2002; Richter and Pawlowski 2007).

Figure 1: Culture contextualization.

This paper focuses particularly on the step

“validate re-usability”. This process includes making

a culture/context analysis and providing decision

support how to transform OKR into culture sensitive

learning materials (cf. Richter and Pawlowski,

2007).

For recommending adaptation strategies, the

focus can be set on the learning resources or system.

Focussing on learning resources, Anand (2005)

suggest adapting linguistic, substantive and cultural

aspects of learning content.

Adapting terms and icons, however, is just as

important as the concept behind. Henderson (2007)

criticizes that without a conceptual model resources

are not becoming sensitive to multiple cultures but

prone to tokenism and stereotyping. According to

Henderson standpoint epistemologies, gender,

minority, workplace culture and eclectic pedagogical

paradigms have to be analysed as well (Henderson,

2007, p.136).

Hence, not only the content but also the layout,

format and learning structure of OKR may require

adaptation strategies.

LMCO 2016 - Special Session on Learning Modeling in Complex Organizations

768

Concerning learning systems, Opperman et al.,

(1997) suggest modifying instances of the interface

such as access to features, interactive dynamics, and

screen layout. Furthermore, functionalities, like

system features, trigger options, search mechanisms

and tools may be adapted (Oppermann et al., 1997;

Buzatto et al., 2009; Specht, 2008).

Specht (2008) elaborates infrastructure and

architecture modules supporting situated needs in

mobile environments. The system concludes on base

of user data which are the most likely useful

resources in a given locality (Specht, 2008).

The brief summary outlines that several

strategies for learning resource and system

contextualization exist. Yet, the factors which

support the decision making ‘which strategy suits

best’ in a given time and space’ are difficult to

define. Factors depend on specific user needs, the

time and efforts which can be invested.

Developing an adaptivity system, i.e. a

contextualization model which is based solely on

automatic inferences of user information is thus not

recommended (cf. Richter and Pawlowski 2007;

Oppermann et al. 1997). Sometimes, contextualiza-

tion is not useful for certain groups of learners. If the

context of users is sufficiently similar, for example,

of close friends or students visiting the same course,

the effort to adapt the content does not advance the

resource but raise the cognitive load of learners

(Katz and Te'eni, 2007). Hence, recommended

contextualization strategies how to re-use a resource

and collaborate inhibit the normal exchange process

and constrain instead of enable the re-use.

Taking previous models into account suggests

developing a semi-automated contextualization

model. Depending on input of users about culture

and context factors and the resource at hand,

adaptation strategies can be recommended. This

argumentation will be further qualified below.

Beforehand, adaptation strategies will be outlined.

To improve learning experiences, numerous

contextualization strategies have been defined. Due

to limitations of space, a comprehensive overview of

the renowned adaptation strategies by Okada et al.,

(2012), is outlined in the Table 1 below.

Table 1: Overview of adaptation strategies.

Translate

Versioning: Implementing specific changes to

update the resource

S1

Translating: Restating content, idioms and

expressions from one language into another

language

S2

Localize

Re-authoring content: Transforming the content

by adding an own interpretation, reflection, practice

or knowledge

S3

Re-authoring structure

Adapt structure, format, or layout of the resource

S4

Re-illustrating: Changing content or adding new

factual information in order to assign meaning,

make sense through examples and scenarios

S5

Personalizing: Aggregating tools to match

individual preference, context and performance

S6

Discussing: Discussing with peers or superior to

settle a meaning of the content

S7

Modularize

Summarizing: Reducing the content by selecting

the essential ideas

S8

Repurposing: Reusing for a different purpose or

alter metadata, tasks and abstract to make more

suited for different learning goals or outcome

S9

Re-sequencing: Changing the order or sequence

S10

Decomposing: Separating content in different

sections, break content down into parts

S11

Ori

g

inate

Remixing: Connecting the content with new media,

interactive interfaces or different components.

S12

Assembling: Integrating the content with other

content in order to develop a module or new unit

S13

Redesigning: Converting contents from one form to

another, presenting pre-existing content into a

different delivery format.

S14

Developing anew: Developing your own OER,

taking reference to existing ones

S15

The strategies are comprehensive and

complementary. For example, summarizing and re-

sequencing serve the means to modularize an OKR;

i.e. slicing it into smaller components or modules.

But to which culture contextualization problems

do the strategies provide a solution? Before outlining

the contextualization model, the methodology and

research approach of the authors will be outlined in

the following.

3 METHODOLOGY

The research approach of authors follows mixed

methods (Creswell and Plano Clark, 2011). The

analysis is shaped by the constructivist

(interpretivist) epistemology and ontology of the

authors. The methodology followed to construct a

culture contextualization model for the public sector

is action design research (Sein et al., 2011). ADR

proposes a set of steps and principles to follow for

creating a model (design artefact). Core steps and

principles are outlined below in Table 2.

Table 2: ADR methodology.

Problem formulation

Practice

inspired

Public administrations face pressure and look

for a solution how to learn, acquire and

exchange knowledge effectively

Theory

ingrained

Contextualization and culture models are

guided by meta-theoretical frame such as AST

(structuration theory)

Culture Contextualization in Open e-Learning Systems - Improving the Re-use of Open Knowledge Resources by Adaptive

Contextualization Processes

769

Table 2: ADR methodology (cont.).

BIE

Reciprocal

shaping

Open e-Learning systems are assemblages,

factors interact and change over time

Mutually

influential

roles

Increasing knowledge of researcher, experts,

users of open e-Learning systems modify the

model over time

Authentic,

concurrent

evaluation

The culture contextualization model is

evaluated iteratively, also single components

(such as the culture model) are iteratively

assessed and improved

Reflection and learning

Guided

emergence

On-going evaluation secures progress,

incremental improvement of the model

Formalized learning

Generalized

outcomes

Suggest models, discuss design principles,

engage in the research domain

This position paper serves to evaluate and

formalize learning. Following a constant back and

forth between researchers, experts and public

employees, requirements, culture factors and

contextualization processes have been clarified. At

this point, the synthesis and evolving model of

cultural contextualization is advanced to experts in

e-Learning, use of OKR and public sectors.

In the following, the culture contextualization

model will be presented.

4 CULTURE

CONTEXTUALIZATION

MODEL

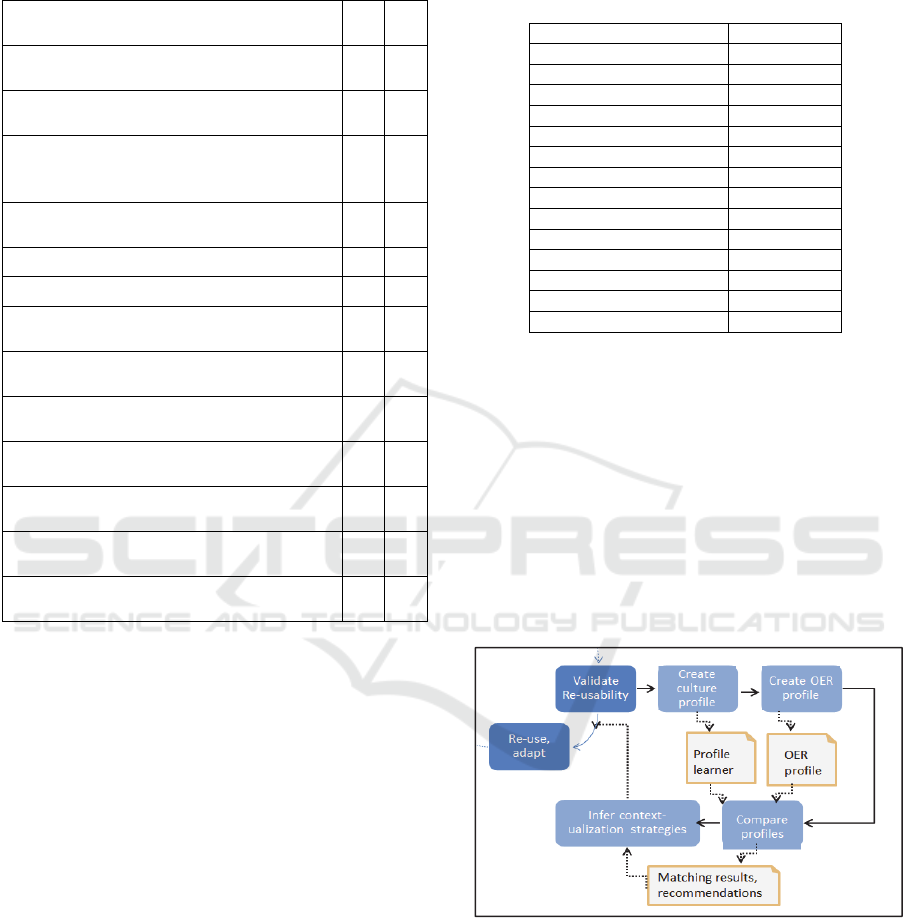

As indicated, the culture contextualization model

presented in this paper focuses particularly on the

step “validate re-usability”. Hence, learners do

already have a potential learning resource at hand.

Either, the resources appears not to meet all needs of

the user; for example, the topic is fine but large parts

are not relevant. Or the learner notices that she is

blocked in using the resource as originally intended.

The model departs from this situation. In the first

step, the model will be presented as a scenario (see

Figure 2 for illustration). Subsequently, the model

artefacts such as the culture and OKR profile will be

presented.

4.1 Model Description

High Level Description: A user decides to validate

the re-usability of an OKR. She proceeds to create

her culture profile by help of a questionnaire. The

questions correspond to the cultural factors of the

model from Stoffregen et al., 2015 (forthcoming).

Thus, the questionnaire provides her an individual

profile based on the answered questions.

The system keeps the profile in the learning

system. Subsequently, the learner creates the OKR

profile. She is guided by a set of questions helping

her to create a profile of the OKR. The profile is

saved in the learning system.

Subsequently the learner proceeds and lets the

system compare the learner and OKR profile. Where

a mismatch occurs, the system provides an

adaptation strategy. For example, the learner prefers

practice based examples while the text provides

theoretical principles. Based on this mismatch, the

strategy ‘re-authoring the structure’ (S4) is

recommended

Based on the comparison of profiles, the learner

can infer a contextualization strategy. As a result,

the step “validate re-usability” ends and the learner

proceeds with the step “use / adaptation”.

Detailed description (example): A learner

decides to validate the re-usability of an OKR. By

doing a specific survey, her culture profile can be

saved. The profile is represented as a list of zero and

ones in the system. It is created by answering yes or

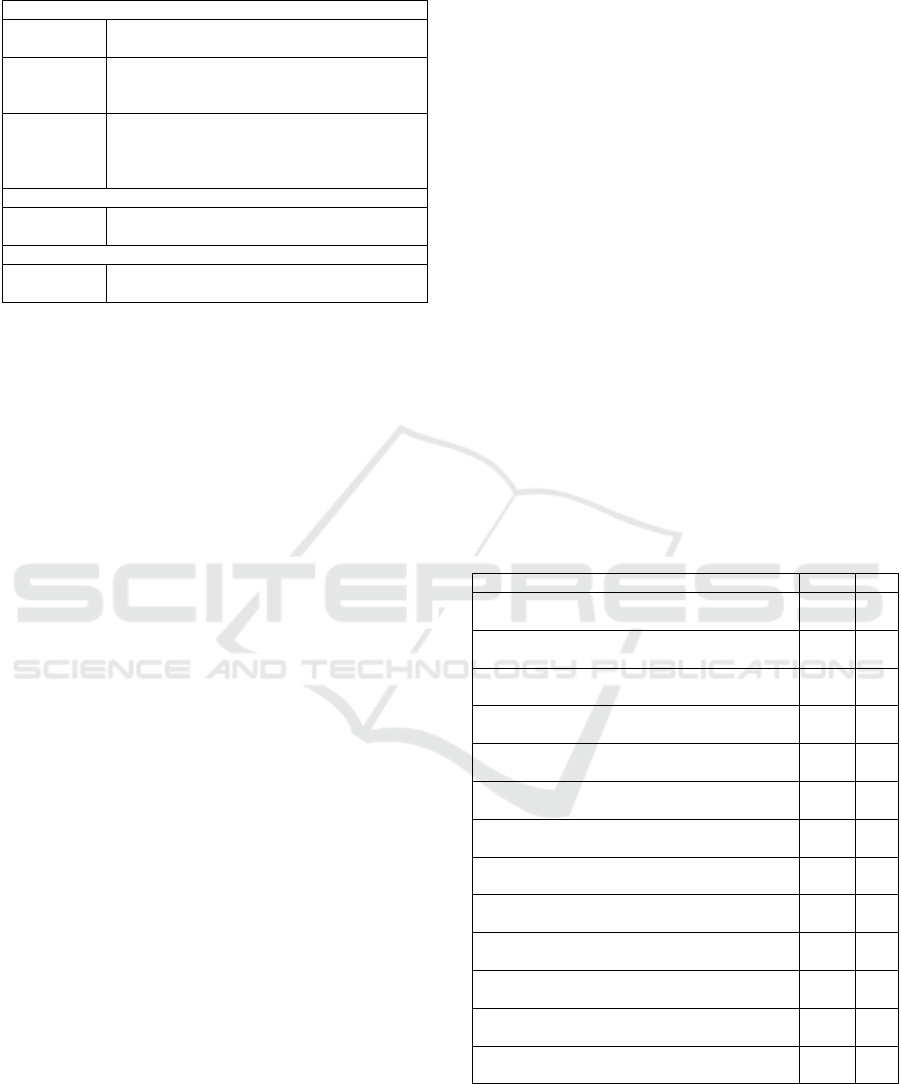

no to the following set of questions (Table 3).

Table 3: Learner profiling.

Statements for profiling Yes (0)

N

o (1)

F1) Public employees have to innovate work

routines

1

F2) Public employees have to discuss about

errors at the workplace.

1

F3) Public employees have to be free in

choosing their learning resource

0

F4) I prefer abstract, theoretical learning

contents instead of applied examples

1

F5) I assume that diversity of learning

preferences must be accommodated

0

F6) I assume that my superiors monitor my

learning activities

1

F7) Superiors have to support the adaptation of

OKR actively

1

F8) Higher administration levels have to

promote their support of OKR

01

F9) OKR of authors who are working in a

different domain are useful for me

0

F10) OKR of authors who are located in broad

distance are useful for me

1

F11) Infrastructure is the main barrier to

adaptation of OKR

1

F12) Time to complete OKR adaptation before

learning has to be scheduled in advance

0

F13) OKR activities have to be regulated by

law.

0

Subsequently, the user proceeds with the analysis

of OKR. The learning system provides the learner a

set of questions. By responding with yes or no, the

user creates a culture and context profile of the OKR

which is saved as zero or ones in the system (see an

LMCO 2016 - Special Session on Learning Modeling in Complex Organizations

770

example in Table 4).

Table 4: Profiling OKR.

OKR profile

Y

es (0

)

No

(1)

F1) Does the OKR suggest shifting your work

routine?

0

F2) Do you have to discuss errors with colleagues,

authors or anyone else?

1

F3) Do you have to ask dedicated personnel

(experts, superior) whether this resource is

appropriate to adapt?

1

F4) Does the OKR provide you with theoretical

concepts only?

0

F5) Is the OKR available in several media types? 0

F6) Is the use of this OER is monitored? 1

F7) Does it seem that you require support from

superiors to actually use the OKR?

1

F8) Do you require support from higher levels to

actually use the resource?

0

F9) Does OKR address other work domains than

yours?

0

F10) Does OKR address issues of departments in

broader distance?

1

F11) Could you use the OKR with the technical

infrastructure at hand?

1

F12) Would you have to complete adaptation in a

predetermined time?

0

F13) Would you have to check whether the use

conflicts with laws or policies?

0

Based on the input of a learner, the system has

two profiles, namely for the learner and the OKR.

Both are saved as a set of zero and ones for a given

factor (n1-13) outlined above.

Based on the request of the learner, the system

compares the profiles. Better to say, the system

calculates the sum for each factor based on the

values for both profiles (equations 1,2):

a= {0,1,2}

(1)

a = Fn

Learner

+ Fn

OKR

and n

Learne

r

≡ n

OKR

(2)

If the factors of profiles mismatch, the value is one.

If the factors match, the sum is either zero or two.

Based on the sum of profile values for each factor,

simple inferences can be drawn.

Our current mapping of culture and context

factors to adaptation strategies is outlined below

(Table 5). A more comprehensive overview can be

provided to the LMCO on demand.

The interface of the user does not show the table

above. Instead, the set of recommended adaptation

strategies and reasons for the recommendation are

provided. Based on the recommendation, the learner

can decide, depending on her available time, which

strategy to embark.

Table 5: Recommendation of strategies.

IF n=1 and

=1 then

Do S7

IF n=2 and

=1 then

Do S6

IF n=3 and

=1 then

Do S6,S8

IF n=4 and

=1 then

Do S12,S4

IF n=5 and

=1 then

Do S14,S13

IF n=6 and

=1 then

Do S15

IF n=7 and

=1 then

Do S9

IF n=8 and

=1 then

Do S6

IF n=9 and

=1 then

Do S3

IF n=10 and

=1 then

Do S2

IF n=11 and

=1 then

Do S11

IF n=12 and

=1 then

Do S6

IF n=13 and

=1 then

Do S5

IF n=i and

=0 then

Do S1

IF n=i and

=2 then

Do S1

The culture contextualization model as presented

(see Figure 2) meets several design criteria for

developing open e-Learning systems. Following

Lane (2010), the model is designed for access (1)

since anyone who is interested in adapting his OKR

can use the model. The model also gives learners

agency (2) by suggesting a set of complementary

adaptation strategies to choose from. Last but not

least the model is designed for participating and

experience (4,5) by letting learners do adaptations

on their own and learning to judge how to adapt

OKR for their cultural preferences.

Figure 2: Culture contextualization model.

Classifying the model in general terms, a semi-

automated contextualization process has evolved. It

belongs to adaptivity systems since it is responsive

to particular learners and OKR albeit dependent on

the learner’s analysis during profiling. Benefits,

difficulties and discussion points in this respect are

outlined in the following.

Culture Contextualization in Open e-Learning Systems - Improving the Re-use of Open Knowledge Resources by Adaptive

Contextualization Processes

771

4.2 Discussion

The contextualization model supports the decision

process of a learner how to adapt a learning resource

given the OKR and their cultural profile.

Domain experts may criticise that the culture

contextualization model above could be improved

by further automation. For example, metadata of the

OKR can be gathered automatically for an analysis

of the geographical distance of the learner and the

learning resource (culture factor ‘10’). Also the time

needed for completing a resource may be retrieved

on base of metadata or calculated on behalf of

specified algorithms (culture factor ‘12’)

Focussing the cultural profile of learners, a

contextualization model may also benefit from

taking user behaviour with online systems into

account. For example, if the use of online websites

or resources takes no longer than ten minutes,

recommendations how to decompose learning

resources to the respective workload can be

provided. While automation by metadata sounds

smart, the realization often lacks due to missing or

ambiguous attributed metadata (Richter and

Pawlowski, 2007). Also, online behaviour to be

analysed by systems may not provide useful

information for contextualization.

The model presented so far, in contrast, takes

advantage of the judgement of users. They can

specify based on their analysis and localized view on

an OKR which recommended adaptation strategy

will contribute most to their learning experience.

Assuming the expertise of users, however, may

have contrary results if the contextualization process

is done by novel learners. They are unfamiliar with

the look and feel of learning resources as well as

activities needed to adapt OKR for own learning

means. Basing contextualization processes on the

input of learners may thus be ineffective.

Despite that the presented contextualization

model may raise the cognitive load of novel OKR in

the first adaptation steps, it is commonly expected

that users learn to accomplish system processes by

doing. The contextualization model is indeed built

upon this premise:

As it has been outlined above, the cultural model

poses several potential adaptation strategies to users.

For example, decomposing and sequencing OKR

both leads to modify the time needed for single

learning modules. Learners have to decide for

themselves which strategy is best given their time

and needs. This freedom to choose allows users to

choose between strategies, take their increasing

experiences into account and to explore strategies

from time to time anew. They become experts and

creative re-users of a learning resource for their own

learning means.

Put in other words, by recommending a set of

complementary adaptation steps, users are invited to

get to know different adaptation strategies and thus

learn by applying different strategies over time.

Based on that, the learning and decision process is

not predetermined but stimulated to unfold.

While the contextualization model appears as a

reasonable process to support public employees in

the choice how to adapt OKR, there are still a few

salient questions to address.

Firstly, the assumption of ‘design for agency’

(Lane, 2010) and related recommending multiple

adaptation strategies to support decision making

processes about adaptation strategies has to be

reconsidered. So far, well received recommendation

practices base on heuristic inferences as well (cf.

Edmundson, 2007). Yet, the straightforward

mapping of particular culture factors to strategies

needs to be further empirically proven.

More than that, the scope of recommendations

needs to be clarified. For example, if a mismatch of

learners indicates that the openness in discourse

(culture factor ‘1’and ‘2’) is weak at the workplace,

not only OKR adaptation but further environmental

strategies should be recommended. Yet, no model

specifies corresponding strategies (cf. Edmundson,

2007). The environmental strategies could suggest

making a workshop for team building, developing a

communication guidelines or else. Hence, inferences

based on the profile mapping need to be empirically

grounded and to be extended by organizational

strategies.

Apart from the mapping of strategies to cultural

factors, another discussion point is whether the

thirteen proposed culture factors (Stoffregen et al.,

2015, forthcoming) are clearly formulated and

unambiguously applied for creating an OKR and

learner profile. While the essence of the factors has

been strongly supported by experts (Stoffregen et al.,

forthcoming), the way how culture factors are

embodied and ‘read’ of an OKR requires further

research (Henderson, 2007; Akrich, 1995)

In this respect, a last crucial point not considered

in the argumentation logic of the contextualization

system is the role of factor magnitude. For example,

if the OKR and learner profile totally mismatch, it

does not make sense to recommend fifteen strategies

for adaptation means. Creating an OKR from

scratch, re-start the search or use only parts of an

OKR may be better recommendations. But is there a

threshold how many adaptation strategies to

LMCO 2016 - Special Session on Learning Modeling in Complex Organizations

772

recommend? Do seven profile-mismatches indicate

that the learner should create an OKR anew or ten

mismatches?

Based on these considerations, we propose to

address the following research gaps and discussion

points in the future:

User Preference and Effort Calculation: How

to prioritize recommended contextualization

strategies? How to attach weights to avoid that

users have to select among ten contextualization

strategies?

OKR Profile Analysis: How do novel users of

open e-Learning systems identify culture factors

of OKR?

Learning by Doing: How does culture

contextualization enhance learning processes of

culture and OKR analysis?

Mapping Culture Factors and Strategies:

Which adaptation strategy is the most promising

for which culture factor?

Adaptivity of the Model: How can automation

of the presented contextualization model be

included without anticipating the learning effect

of learners?

The presented questions will be further qualified and

discussed with experts between January and March

2016. The set of scheduled workshops will

empirically validate the culture contextualization

model presented in this paper.

To formalize learning of the presented model and

development process, further discussion with

domain experts is needed to improve the model

towards a framework. At the LMCO, initial

discussions can be launched in this respect, as well

as with regard to presented research gaps and

discussion points.

5 CONCLUSIONS

The position paper has presented a culture

contextualization model. It is dedicated to the public

sector, particularly the adaptation of open

knowledge resources by public employees.

The presented model is an adaptive and semi-

automated rule-based mechanism. Based on the

qualified input of learners, a culture profile of the

learner and OKR is created. Given the match of the

profiles, a set of comprehensive and complementary

adaptation strategies are recommended.

For learners, the contextualization model is

design for agency, access and empowerment. Over

time, learners become more knowledgeable about

different suggested learning strategies and learn

which factors are critical for a positive learning

experience.

Above and beyond, there is much potential for

discussing and improving the model. Examples to be

discussed at the LCMO are the role of automation

processes during contextualization, the mapping of

culture factors and

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research has been co-funded by the EU, FP7-

ICT programme, grant no: 619347.

REFERENCES

Akrich, M., 1995. User Representations: Practices,

Methods and Sociology. In Rip, A., Misa, T. J., Schot,

J. Managing Technology in Society. The Approach of

Constructive Technology Assessment. pp.167–184.

Anand, P., 2005. Localizing E-learning. Knowledge

Platform [online]. Available at http://www.

knowledgeplatform.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/

Localizing_E-Learning.pdf Accessed Aug. 2015.

Bimrose, J., Brown, A., Holocher-Ertl, T., Kieslinger, B.,

Kunzmann, C., Prilla, M., 2014. The Role of

Facilitation in Technology-Enhanced Learning for

Public Employment Services. International Journal of

Advanced Corporate Learning 7(3), pp.56–64.

Buzatto, D., Anacleto, J. C., Dias, A. L., Silva, M. A. R.,

Villena, J., de Carvalho, A., 2009. Filling out learning

object metadata considering cultural contextualization.

SMC 2009. IEEE International Conference on

Systems, Man and Cybernetics, 2009. IEEE

International Conference on SMC.

Chen, T-L., 2014. Exploring e-Learning Effectiveness

Perceptions of Local Government Staff Based on the

Diffusion of Innovations Model. Administration &

Society 46(4), pp.450–466.

Conradie, P., Choenni, S., 2012. Exploring process

barriers to release public sector information in local

government. In Ferriero, D., Pardo, T.A., Qian, H.,

Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on

Theory and Practice of Electronic Governance.

Albany, NY, USA, October, ACM, pp.5-13.

Creswell, J. W., Plano-Clark, V. L., 2011. Designing and

conducting mixed methods research. USA: Sage

Publications, Ltd.

Dunn, P., Marinetti, A., 2002. Cultural

adaptation: necessity for e-learning. LineZine. [online]

Available at Available at: http://www.linezine.com/

7.2/articles/pdamca.htm, checked on 10/8/2014.

Eidson, L. A. K., 2009. Barriers to E-Learning Job

Training: Government Employee Experiences in an

Online Wilderness Management Course. Thesis,

Culture Contextualization in Open e-Learning Systems - Improving the Re-use of Open Knowledge Resources by Adaptive

Contextualization Processes

773

Dissertations, Professional Papers. University of

Montana. Paper 86.

Edmundson, A., 2007. The cultural adaptation process

(CAP) model: designing e-learning. Chapter XVI. In

Edmundson, A., Globalized e-learning cultural

challenges. Hershey, PA: IGI Global, pp.267–289.

Henderson, L., 2007. Theorizing a multiple cultures

instructional design model for e-learning and e-

teaching. In Edmundson, A., Globalized e-learning

cultural challenges. Hershey, PA: IGI Global, pp.130–

153.

Katz, A., Te'eni, D., 2007. The Contingent Impact of

Contextualization on Computer-Mediated

Collaboration. Organization Science 18(2), pp.261–

279.

Lane, A., 2010. Designing for innovation around OER.

Journal of Interactive Media in Education, 2010(1),

pp.1–10.

Mikroyannidis, A., Okada A., Connolly T., Scott P.,

Pirkkalainen, H., Holtkamp, P. et al., 2010. D3.1

Adaptation Strategy. Open Scout. EDU 428016,

eContentplus programme, ECP 2008, pp.1–79.

Okada, A., Mikroyannidis, A., Meister, I. and Little, S.

2012. “Colearning”- collaborative networks for

creating, sharing and reusing OER through social

media. In OCW, SCORE, Cambridge: Innovation and

Impact - Openly Collaborating to Enhance Education.

April 2012, Cambridge, UK.

Oppermann, R., Rashev, R., Kinshuk, N.n., 1997.

Adaptability and adaptivity in learning systems. In

Behrooz, A., Knowledge Transfer. Proceedings on

Knowledge Transfer, July 1997. London, England:

Pace, pp.173–179.

Richter, T., Pawlowski, J., 2007. The need for

standardization of context metadata for e-learning

environments. In Proceedings of e-ASEM Conference,

Seoul, Korea.

Schein, E., 2010. Organizational Culture and Leadership.

The Jossey-Bass Business & Management Series. San

Fransicso: Wiley Online Library.

Sein, M. K., Henfridsson, O., Purao, S., Rossi, M.,

Lindgren, R., 2011. Action Design Research. MIS

Quarterly 35(1), pp.37–56.

Specht, M. 2008. Designing Contextualized Learning. In.

Adelsberger, H. H., Kinshuk, N. N., Pawlowski, J.,

Sampson, D. G., Handbook on Information

Technologies for Education and Training. Springer

Berlin: International Handbooks on Information

Systems, pp.101-111.

Stoffregen, J., Pawlowski, J.; Scepanovic, S.; Zugic, D;

Ras, E., 2015. Identifying Socio-cultural factors which

impact the use of Open Knowledge Resources in local

public administrations, (submitted).

LMCO 2016 - Special Session on Learning Modeling in Complex Organizations

774