Online Stress Management: Design for Reflections and Social

Support

Åsa Smedberg

1

, Hélène Sandmark

1

and Andrea Manth

2

1

Department of Computer and Systems Sciences, Stockholm University, Postbox 7003, SE-164 07 Kista, Sweden

2

The Swedish Post and Telecom Authority, Postbox 5398, SE-102 49 Stockholm, Sweden

Keywords: Online Self-help, Online Stress Management, Preventive Care, Self-reflection, Social Support.

Abstract: An increasing number of people suffer from high levels of stress and experience strong and unhealthy

reactions to different stressors. Various kinds of applications for self-help are available on the Internet.

However, the technology for stress management purposes is still in its early phase. This paper presents the

ideas behind the design of an artifact that combines different technologies and offers support for individual

as well as social reflections. The work is anchored in conventional system development methods and

interdisciplinary research in the field of e-health. It is based on the holistic idea of combining areas of self-

help, evidence-based information and learning through feedback and communication in groups and with

experts that have been manifested in a web-based stress management system. The work presented in this

paper is a further development towards integration of different technologies and learning aids. It integrates a

mobile phone app with a web-based system for people with stress management issues. The proposed system

supports social reflections through the possibility to share reflections in various social forums.

1 INTRODUCTION

Sick leave due to mental illness is a growing

problem in Sweden and other countries in the

Western world. High levels of stress have become an

increasingly common condition in people's everyday

lives. Work life is more complex than previously

and puts demands on our cognitive abilities to keep

up with technological developments, increased

competition and constant change. Factors in certain

areas of the work environment such as work

organization, management, hierarchy, and

interpersonal relations can trigger stress reactions

which are associated with psychosocial strain. Great

demands from the outside world can lead to

unhealthy stress levels in individuals. Grandey and

Cropanzano (1999) describe how the requirements

of the job and at home have grown for the whole

family. There is also a historical expectation that

women take care of the family. Multiple demands

from family and work can increase negative stress

and be a challenge especially to women's health and

well-being, and a determinant for long-term sickness

absence and less well-being. Several studies have

shown that those who have multiple roles and

demands are more exposed to negative stress,

resulting in physical and psychosocial dysfunctions

(Scharlach, 2001; Nordenmark, 2004; Hallsten et al.,

2002).

Earlier studies found that domestic workload,

mainly connected with own children, has increased

for men and women, but to a greater extent for

women during the past twenty years (Lundberg et

al., 2003; Voss et al., 2001).

The load in family life and in the workplace is

considered to have a correlation. Grandey and

Cropanzano (1999) point out that the strain grows

significantly when the discrepancy between the

expectations of the family and the expectations from

the workplace increases, and if any of the areas have

to stand back.

However, it is a rather complex issue, since

people react differently and to different stressors.

People who work and live under the same conditions

can therefore react in different ways. The

individual's subjective experience of a condition and

a situation affect whether and what symptoms are

developed (Henderson et al., 2011). Stress is an

individual combination of external reality, individual

perception of the situation and the estimated

capacity to solve the problem.

Some people require a change in lifestyle to deal

Smedberg, Å., Sandmark, H. and Manth, A.

Online Stress Management: Design for Reflections and Social Support.

DOI: 10.5220/0005706901170124

In Proceedings of the 9th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2016) - Volume 5: HEALTHINF, pages 117-124

ISBN: 978-989-758-170-0

Copyright

c

2016 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

117

with problems of stress reactions. Continuous and

social support has shown helpful when managing

stress and change of lifestyle (Karasek and Theorell,

1990). Studies have shown that the social aspect of

learning is also important to consider, and to reflect

together with others. Online support groups and

reflection tools have shown to influence people with

the symptoms of stress positively (Sandmark and

Smedberg, 2013).

Tools that address e-health come in many

different shapes and technologies. The technologies

differ in strengths; mobile phones can be used

independently of space, apps tend to have defined

tasks, while computers are normally better suited for

processing information and doing analysis.

Regarding systems for stress management, there is

no consensus regarding how such a system should

be designed in order to combine on the one hand the

advantages of different technologies, and on the

other hand complementary areas of e-health, such as

self-help, social and individual reflections,

communication and information. This paper will

investigate a holistic design where different

components and technologies are combined. Design

Science was used as a framework to iteratively build

a prototype of an online stress management system.

The system is a development of the web-based stress

management system described in previous

publications (see Smedberg and Sandmark, 2012,

e.g.).

The next section (section 2) discusses stress

management and online self-help. The following

sections (section 3 and 4) describe the design

considerations and the proposed system, followed by

a user scenario (section 5) and, finally, conclusions

and future work (section 6).

2 BACKGROUND

2.1 Stress Management

Stress is about biological and psychological

responses to situations that are perceived as

threatening or challenging. A stress reaction is

caused based on an individual combination of

external reality, the human perception of the

situation and the estimated capacity to solve the

problem.

To manage work-related stress, effective

interventions connected to the workplace are

necessary. Interventions regarding stress in the

workplace could focus on the individual or on the

organizational level (Czabala et al., 2011). Thus

there are two different approaches to manage work-

related stress. At the individual level, relaxation and

cognitive-behavioural techniques have been applied

to improve an individual’s mental resources and

responses. At an organizational level, job adjustment

and workplace communication activation have been

applied in order to improve the occupational context.

However, in earlier intervention studies

regarding the organization level the effect was

limited. Individual level interventions such as

cognitive-behavioural approach comprising coping

techniques has so far been found to be more

effective, although the long term effects are not yet

fully known (Giga et al., 2003; Czabala et al., 2011).

2.2 Self-help Online

Barak et al. (2008) emphasize that the

communication in online communities influence on

people's well-being positively and that the writing

process is a good technique to structure thoughts and

feelings. When sharing experiences one has also

begun to reflect on these. Barak et al. (2008)

describe how the online forums can increase people's

personal empowerment and may affect their ability

to make decisions. The observed positive effects

depend, among other things, on confirmation from

the group. The individual wants to be understood

and have the experienced situation acknowledged by

the others. Also the fact that participation is

voluntary and that you can help others with your

own experiences is beneficiary when personal

empowerment is concerned. To share burdensome

emotions with others and to feel socially involved in

the group have shown to result in a sense of relief

(Barak et al., 2008).

A positive self-image and social identity affect

people's mental health (Aneshensel et al., 2013).

Wenger (2004) describes how social identity can be

shaped and social learning take place in

communities. He argues that individuals are

influenced by others through the group views and

competences presented in the community. In order

to have a healthy community, learning should also

take place on the boundaries, according to Wenger.

This means that we need to be open for new ideas,

‘experience in the world’, and have them combined

with the competence of the community.

Positive effects such as greater empowerment

have been seen in patients who engage in online

support groups (Barak et al., 2008; van Uden-Kraan

et al., 2008). Online support groups constitute a self-

management tool that allow for an autonomous

patient role (Barrett, 2005; McGowan, 2005).

HEALTHINF 2016 - 9th International Conference on Health Informatics

118

Through the group, experiences, advice and

recommendations can be shared.

One possible disadvantage of these types of peer-

to-peer groups is that they can spread

misinformation which leads to unhealthy behavior. It

can also take some time before people feel

comfortable in the group (Barak et al., 2008). Barak

notes that online groups do not replace the necessary

therapy.

2.3 Self- and Group-reflections

Self-reflection is one tool among other to manage

stress reactions and deal with situations that cause

stress. Reflections on situations can help people

understand what is beneficiary and what causes

disadvantages to their health.

Reflection is about discussing situations that are

perceived to be complex or uncertain (Creek and

Lougher, 2008). By reflecting, one can illuminate a

situation from different angles and correct the

mental image that was constructed initially. Self-

reflection can then reform the perspective of a

situation or action (Mezirow et al., 1990).

Mezirow et al. (1990) describe how critical

reflection triggers learning in individuals. Among

other things, they describe how critical self-

evaluation helps people to re-evaluate their

experiences, knowledge, beliefs, feelings and

actions. They believe that critical reflection aims at

the question "Why?", and that the answer will be the

causes and consequences of one's actions in the

future. They also point out that the critical self-

reflection is a highly significant method for learning

among adults.

Westberg and Jason (2001) ask the question why

reflection and self-evaluation are important. Results

from studies of medical care students show that

reflections help students build new skills. Reflection

helps to identify gaps in knowledge and correct the

error in reasoning. By reflecting and be self-critical,

learning time can also be shortened. As an example,

Westberg and Jason (2001) refer to trainers that let

athletes look at their own performances and evaluate

them critically. The method has shown to increase

the rate of learning in athletes.

3 DESIGN CONSIDERATIONS

The practical work with the design of a system

prototype for self-reflection was done iteratively

outgoing from interdisciplinary research in the area

of stress management online. The holistic idea of

combining ICT tools for self-management,

evidence-based information and learning through

feedback and communication in groups and with

experts have been investigated in previous studies

and manifested in a web-based platform (Smedberg,

2007; Smedberg and Sandmark, 2011). The

prototype for self-reflection was designed through

four iterations, each with the following steps: 1) a

discussion in the online stress management team to

clarify the problem to be solved and the

requirements, followed by 2) development and

demonstration, and then 3) evaluation of the

prototype version by the online stress management

team. Below, the basic considerations for the design

of the prototype are presented.

3.1 Preventive Care

The design should consider the aspects of preventive

care. Since the target group is people with stress

symptoms, the system is to support them in their

daily working or student life, and to help them reach

increased well-being. Stress exists in all persons in a

varying scale. It is manifested differently in people,

and it also accelerates through different phases,

according to Selye (1985). It is therefore beneficiary

for the user if one can be aware of unhealthy stress

levels and associated problems as early as possible.

3.2 Analysis of Data and Trends for

Self-reflection

The user must have the ability to process and

analyze data in order to change behavior in the

future. As discussed earlier, reflection has shown to

be an effective learning method (Mezirow et al.,

1990). It is therefore important to be able to see

trends and historical data of the stressful situations

that the user experiences.

To serve this purpose, the prototype should

support the collection and presentation of different

pieces of data related to the stressful situations of the

user. Stress levels, textual descriptions, images, time

and a geographical context are examples of types of

data that are related to the stressful situations of the

users.

To customize the visualization of trends is also

important, and to be able to focus on a certain period

of time. It is important to note trends to be able to

reformulate one’s perception so that new values can

be applied in future decisions and actions (Mezirow

et al., 1990).

In the prototype, it should be possible to

highlight a situation as private or work-related.

Stress-related problems often increase when stressful

situations occur in both private and work-related

Online Stress Management: Design for Reflections and Social Support

119

contexts, according to Grandey and Cropanzano

(1999). If this data is made visible, trends and

patterns can be analyzed and changed.

3.3 Sharing for Social Support

A system should take into account the good

influences that online social groups have

demonstrated. Support from other members can

create a social identity (Wenger, 2009), increase

self-confidence and contribute to a positive self-

image. Communication in social groups and online

forums has shown positive effects, such as increase

in self-respect and empowerment among the users

(Barak et al., 2008). The prototype should therefore

also support the need to gain social support and not

only focus on individual reflections.

3.4 Holistic Design - Complementary

Knowledge and Actors

Different actors, both experts and peers, have shown

to be able to share complementary understanding of

health-related issues in online systems (Smedberg,

2007). While peers contribute with their experiences

and practical advice, for example, medical experts

can offer in-depth knowledge and understanding of

different health-related issues. For the prototype, this

means that both experts and peers are to be regarded

helpful for social support and group-reflections.

The prototype is also to be integrated with the

existing web-based platform that supports the

combination of different knowledge and

experiences. In this system, there are functions for

communication with both stress experts and peers

implemented already. The existing functions are:

Ask-the-expert, Forums for peer communication,

Online consultation for group counselling session

(chat), Practical exercises (text as well as sound and

video recordings) and Stories told and research

results (see e.g., Smedberg and Sandmark, 2012).

The different functions are organized in four

different stress management areas: Sleep, Work and

studies, Balance in life and Physical well-being.

3.5 Simplicity

The design must be simple, especially since the

target group is people with stress symptoms, it is

important not to increase the level of stress caused

by system complexity. It is important to remember

that people with symptoms of stress may have

physical and mental constraints. The prototype uses

accepted design principles according to Nielsen

(2001) and the recommendations of the Swedish

Government's Workgroup Use Forum (2014).

Particular emphasis has been placed on the

principles of "Simplicity" and "Understanding the

context" in these recommendations.

In rule 53 of the design guidelines recommended

by Nielsen (2001), it is said that the system should

offer the user direct access to high-priority

information. This is also relevant for the design of

the prototype.

3.6 Flexibility

Considering the differences among people with

stress issues, their lives, experiences and stress

reactions, the design of online stress management

systems need to be flexible. Since stress is also

affected by the level of control, stress management

online has to let the user experience a sense of

control and be empowered. This includes being able

to freely navigate in the system, to get the

information wanted and choose whom to talk to. The

user should be able to decide if individual reflections

should be in focus one day, and social interactions

and group reflections another day.

4 THE PROTOTYPE

This section outlines the prototype system for self-

reflection that is the result of the iterative design

process and based on the design considerations

presented in the previous section.

4.1 The System Boundaries

The prototype is a web-based system for self-

reflections on stress and patterns of events, and for

initiating reflections in groups. It is fed by data from

a mobile phone app in which events that cause stress

reactions are registered. Data about these events are

then used to visualize patterns of stress reactions –

frequency, scope and time - over shorter and longer

time periods. By putting data in relation to each

other, the user can reflect on unwanted events from a

broader perspective. The goal is also to have the

prototype integrated with the larger web-based stress

management system where social interactions,

reflections and advice from stress experts and peers

can take place.

4.2 Functionality

Stress situations that the user has registered through

HEALTHINF 2016 - 9th International Conference on Health Informatics

120

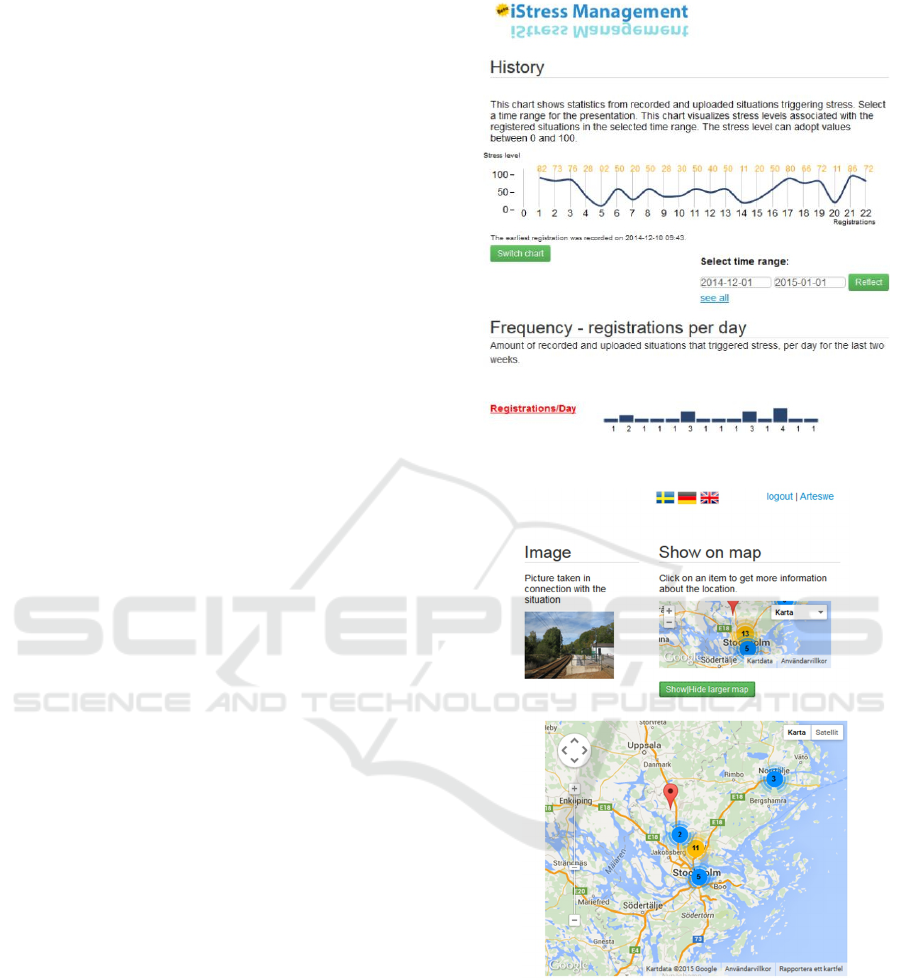

the mobile phone app can be displayed in different

ways in the prototype. The prototype should support

analyses and reflections, with customized display of

data. As can be seen in figure 1, historical data of

events can be presented according to both frequency

and level. The user chooses a time period for the

presentation. In the example in figure 1, the time

period is one winter month and the results show that

during this time frame 22 stress situations were

registered by the user, of which some were classified

as causing high stress levels (80-100) on the scale of

1 to 100. By clicking on a registration presented in

the chart, the date of the registration will be visible.

Figure 1 shows also stress levels of the registered

situations from the last 15 days so that the user can

monitor the latest development of his or her stress

levels.

The prototype offers also a visualization of all

registered situations on a map (see fig. 2). It shows

how many times there have been situations

registered in a particular geographical place. It is

also possible to view the data as a geographical

trend. The places in question are marked out on the

map and different colours are used to illustrate the

frequency of reported stress situations.

When looking at the registered stress situations, one

by one or in a certain time frame, the user can add

his or her reflections. In figure 3, the time frame

chosen is five days in December of 2014. In the

example, ten situations with different stress levels

occurred in this time frame. When looking at the

levels and descriptions of the situations, the user

makes the reflection that the period is characterized

by recurring sleeping problems. In the example, the

reflection is tagged as belonging to the stress area

called “Sleep”. This makes it possible to share the

stress chart and self-reflection, and use it as a basis

for conversations and group-reflections with other

actors, both experts and peers, in the larger web-

system. The user’s own reflections can eventually be

posted in the forum on sleep (for peers) and also

referred to in conversations with the experts in the

larger web-system.

Figure 4 shows an overview of the prototype

with its different functions. To the left, a chart of

past registered stress situations are seen. When

clicking on one of the situations, detailed

information about the situation appears. A

description about the situation is seen below the

chart, and it is possible to edit the text, if the user for

example was not able to write so much at the time

when the situation was registered. If the user has

taken a picture in connection to the stress situation,

this image is shown to the right, together with the

geographical position. The reflections made by the

Figure 1: Interval of stress situations and stress levels.

Figure 2: Stress situations in a geographical context.

user are seen to the right. Different themes and

concerns can be seen in the list of reflections.

Behind each reflection there is a certain stress

situation or interval of stress situations. New

reflections can also be added from here. Also, in

order to work actively with managing the stress

situations and to learn how to deal with them, the

user can define goals (placed at the bottom), and

there are also links to the larger web-based stress

Online Stress Management: Design for Reflections and Social Support

121

management system where the user can engage in

conversations with peers and experts, do exercises,

read about research results, and so on.

Figure 3: Sharing of reflections and stress diagram.

Figure 4: Prototype overview.

4.3 Technical Solution

The mobile phone app, developed earlier, is

integrated with the prototype in the sense that it

sends data to the prototype. Through scripting

language (AngularJS) the logic could be handled,

and HTML was used for the graphical presentations.

The code is executed in a browser when it is actually

being used, and there are no requirements on the

underlying platforms or software. The prototype can

thus be used in all modern browsers and easily

integrated with other systems. The coding work

follows the recommendations from W3C. The idea

was to have the technical solution as generic as

possible to be able to easily integrate the

surrounding systems. The prototype consists of the

markup language HTML 5, style sheets (CSS) for

the graphical presentation and a dynamic JavaScript

based framework (AngularJS).

As data carrier between the mobile phone app

and the prototype, JSON files were used. These are

good for demonstrating the features of the prototype

but will not be used in the final system. JSON files

are platform independent and can easily be packed

together with code and transferred between different

environments. This makes it easy to further develop

the prototype anywhere without losing functionality.

5 USER SCENARIO

This section presents a user scenario in which the

system prototype for self-reflection and its relations

with the surrounding systems for stress management

are illustrated.

Linda, who is an employee at an insurance

company, experiences stress reactions that she

believes are related to her situation with the new job

and her family duties. She downloads the mobile

phone app for self-reflection on stress situations to

her phone and surf around a bit on the related web-

based system to get familiar with the systems. Some

days later, Linda experiences symptoms of stress

when facing a tough meeting with her boss. She

grabs her phone and starts to describe the situation in

a few words and saves it. The same evening at

home, the kids are being very active and the stress

level increases. Again, Linda records the situation in

the phone.

A few hours later, Linda loads the data from her

phone app to the web-based system. Uploaded data

then appear as two registered situations. From here,

Linda marks a situation as private and the other one

as job-related. She also writes some brief notes

about the physical symptoms that arose in

connection with the job-related incident. Then, she

compares the situations with each other and tries to

reflect on the causes and effects.

In the beginning, there is not much data for

analysis. But as the registered situations increase in

number, the comparisons and visualizations of

trends become more meaningful. Eventually, Linda

checks the map to see how often situations have

HEALTHINF 2016 - 9th International Conference on Health Informatics

122

occurred in different geographical contexts and

decides to write a short reflection on a number of

geographical context.

Linda recognizes also that the stress-related

situations usually seem to occur at home and at work

on the same day. She thinks it would be interesting

to hear what others can tell about similar

correlations. Linda decides to post a message in the

forum "Balance in Life". But first, in the popup

window where Linda wrote her reflection, she marks

that she wants to share the reflection in the forum

"Balance in Life". This means that the reflection

together with the underlying stress diagram become

available from the web-based system. When Linda

formulates her question in the forum, the shared

reflection is attached to the message.

Eventually, Linda gets a number of tips from

users who have experienced similar situations. The

answers help her relax since she understands that it

is ok to feel the way she does and that she is not

alone. She also gets some practical advice that she

starts to practice. But some advice is difficult to

understand, and she recalls that there is also a

possibility to ask questions to a stress expert. Linda

then formulates a question to the expert and shares

this time a longer sequence of data from the past

stress situations. The stress expert reconnects with

some tips and explanations and also informs about

an upcoming online chat session in which Linda is

welcome to participate, if she wants to reflect

together with others under the supervision of the

expert.

6 CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE

WORK

In this paper, we have presented the design of a web-

based prototype system that supports individual and

social reflections for people with stress reactions.

The interdisciplinary research that forms the basis of

the prototype design was elaborated.

Visualization of events plays a central role in the

design. It is manifested in the form of graphs

presenting events in relation to each other, events

over time, and the geographic locations of events.

Previous studies have shown that visualization and

evaluation of events that cause undesirable stress

reactions provides a good support for reflections.

In the proposed solution, the user has also the

option to specify whether an event is related either to

a personal or a work-related situation. It has been

shown in earlier research that people are more likely

to fail to cope with stress exposures when both areas

are affected. This might result in a decrease in their

wellbeing. Being more conscious of the different

potential sources of conflicts in work and family life

respectively can help individuals to find effective

strategies.

Both individual reflections and social support

have shown important for changing a negative trend

of stress exposure as well as reactions to stressors.

Therefore, the proposed system presented in this

paper includes the possibility to share one’s

reflections, and also data sequences of stressful

events, with others, both peers and medical experts.

The prototype presented in this paper is part of a

larger online stress management system. It is

integrated with both the mobile phone app where

stress events first are documented, and the web-

based system that allows the users to communicate,

and to access information and exercises. All

together, these integrated subsystems create a

dynamic and combined online stress management

platform, which could give individuals better

opportunities to reduce mental problems due to

stress exposure. The next step is to ensure technical

robustness of the whole system. It is especially

important in regard to security and integrity issues.

So far, empirical evaluations have been restricted to

students and during shorter time periods. Future

empirical evaluations will include a larger group of

employees who experience negative stress together

with stress experts.

REFERENCES

Aneshensel, C.S., Phelan, J. C. and Bierman, A., 2013.

Handbook on the sociology of mental health, Springer,

2

nd

edition.

Barak, A., Boniel-Nissim, M. and Suler, J., 2008.

Fostering empowerment in online support groups.

Computers in Human Behavior. 24(5), 1867-1883.

DOI= http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2008.02.004.

Barrett, M. J., 2005. Patient self-management tools: An

overview. California Healthcare Foundation.

http://www.chcf.org/publications/2005/06/patient-

selfmanagementtools-an-overview Accessed on

September 20, 2014.

Creek, J., Lougher, L., 2008. Occupational therapy and

mental health – Forth Edition, Churchill Livingstone

Elsevier.

Czabała, C., Charzyńska, K. and Mroziak, B., 2011.

Psychosocial interventions in workplace mental health

promotion: an overview, Health Promot Int,

2011:26(1):70–84.

Giga, S.I., Cooper, C.L. and Faragher, B., 2003. The

development of a framework for a comprehensive

Online Stress Management: Design for Reflections and Social Support

123

approach to stress management interventions at work,

Int J Str Man, 2003;10(4):280–296.

Grandey, A. A, and Cropanzano R., 1999. The

conservation of resources model applied to work–

family conflict and strain, Journal of Vocational

Behavior 54, 350–370.

Hallsten, L., Bellagh, K. and Gustafsson, K., 2002.

Utbränning i Sverige – en populationsstudie (Burnout

in Sweden – a national survey). In Arbete och Hälsa

(Work and Health,) National Institute for Working

Life: Stockholm; 2002:6.

Henderson, M., Harvey, S. B., Overland, S., Mykletun, A.

and Hotopf, M., 2011. Work and common psychiatric

disorder, J R Soc Med2011:104, 198 – 207.

Karasek, R. A. and Theorell, T., 1990. Healthy work:

stress, productivity, and the reconstruction of working

life. New York: Basic Books.

Lundberg, U., Krantz, G. and Berntsson, L., 2003. Total

workload, stress and muscle pain from a gender

perspective, J Soc Med, 3:245-254.

McGowan, P., 2005. Self-management: A background

paper. Centre on Aging, University of Victoria.

Mezirow, J., and Associates (eds.), 1990. Fostering critical

reflection in adulthood. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Nielsen, J., 2001. Design guidelines for homepage

usability, http://www.nngroup.com/articles/113-

design-guidelines-homepage-usability/, available on

Feb. 02, 2015.

Nordenmark, M., 2004. Balancing work and family

demand. Do increasing demands increase strain? A

longitudinal study. Scand J Publ Health, 32:450-455.

Sandmark, H. and Smedberg, Å., 2013. Stress at Work:

Developing a stress management program in a web-

based setting. In Proceedings of The Fifth

International Conference on eHealth, Telemedicine,

and Social Medicine, IARIA, 125-128.

Scharlach, A.E., 2001. Role strain among working parents:

implications for workplace and community,

Community Work Family, 4:215-230.

Selye, H., 1985. History and present status of the stress

concept, In A. Monat and R.S. Lazarus, eds. Stress

and coping, 2nd ed. New York: Columbia University.

Smedberg, Å., 2007. To design holistic health service

systems on the Internet. In Proceedings of World

Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology,

November 2007, 311-317.

Smedberg, Å and Sandmark, H., 2011. A holistic stress

intervention online system - Designing for self-help

through multiple help, International Journal on

Advances in Life Sciences, vol 3, no 3 & 4. IARIA,

2011. 47-55.

Smedberg, Å. and Sandmark, H., 2012. Dynamic stress

management: Self-help through holistic system design.

In E-Health Communities and Online Self-Help

Groups: Applications and Usage. IGI Global, 2012.

136-154.

Swedish Government’s Workgroup Use Forum, 2014.

Design Principles for public digital services. (Original

reference in Swedish: Regeringens arbetsgrupp

Användningsforum, 2014. Designprinciper för

offentliga digitala tjänster),

http://www.anvandningsforum.se/designprinciper/,

available on Dec. 01, 2014.

van Uden-Kraan, C.F., Drossaert, C.H., Taal, E., Shaw,

B.R., Seydel, E.R. and van de Laar, M.A., 2008.

Empowering processes and outcomes of participation

in online support groups for patients with breast

cancer, arthritis, or fibromyalgia, Qualitative Health

Research. 18, 405-417.

Voss, M., Floderus, B. and Diderichsen, F., 2001.

Physical, psychosocial, and organisational factors

relative to sickness absence: a study based on Sweden

Post, Occup Environ Med, 58:178-184.

Wenger, E., 2004. Communities of practice and social

learning systems. In Starkey, K., Tempest, S., &

McKinlay, A. (Eds.), How organizations learn:

Managing the search for knowledge, 2

nd

ed., 238–258.

London, UK: Thomson Learning.

Westberg, J. and Jason, H., 2001. Fostering reflection and

providing feedback – Helping others learn from

experience, 1

st

edition, Springer, New York.

HEALTHINF 2016 - 9th International Conference on Health Informatics

124