Analysis of Gender-specific Self-adaptors and Their Effects on

Agent’s Impressions

Tomoko Koda, Takuto Ishioh, Takafumi Watanabe and Yoshihiko Kubo

Department of Information Science and Technology, Osaka Institute of Technology,

1-79-1 Kitayama, Hirakata-shi, 573-0196, Osaka, Japan

Keywords: Conversational Agents, Intelligent Virtual Agents, IVA, Gesture, Self-adaptors, Non-verbal Behaviour,

Gender, Evaluation.

Abstract: This paper reports how agents that performs gender-specific self-adaptors are perceived by Japanese

evaluators depending on their gender. Human-human interactions among Japanese undergraduate students

were analysed with respect to usage of gender-specific self-adaptors in a pre-experiment. Based on the results,

a male and a female agent were animated to show these extracted self-adaptors. Evaluation of the interactions

between agents that exhibit self-adaptors typically exhibited by human male and female indicated that there

is a dichotomy on the impression on the agent between participants’ gender. Male participants showed more

favourable impressions on agents that display feminine self-adaptors than masculine ones performed by the

female agent, while female participants showed rigorous impressions toward feminine self-adaptors.

Although the obtained results were limited to one culture and narrow age range, these results implies the

importance of considering the use of self-adaptors and gender in successful human-agent interactions.

1 INTRODUCTION

Intelligent virtual agents (IVAs) that interact face-to-

face with humans are beginning to spread to general

users, and IVA research is being actively pursued.

IVAs require both verbal and nonverbal

communication abilities. Among those non-verbal

communications, Ekman classifies gestures into five

categories: emblems, illustrators, affect displays,

adapters, and regulators (Ekman, 1980). Self-

adaptors are non-signalling gestures that are not

intended to convey a particular meaning (Waxer,

1988). They are exhibited as hand movements where

one part of the body is applied to another part of the

body, such as picking one’s nose, scratching one’s

head and face, moistening the lips, or tapping the foot.

Many self-adaptors are considered taboo in public,

and individuals with low emotional stability perform

more self-adaptors, and the number of self-adaptors

increases with psychological discomfort or anxiety

(Ekman, 1972, Waxer, 1988, Argyle, 1988).

According to Caso et al. self-adaptor gestures were

used more often when telling the truth than when

lying (Caso, 2006).

Because of its non-relevance to conversational

content, there has not been much IVA research done

on self-adaptors, compared with nonverbal

communication with high message content, such as

facial expressions and gazes. Among few research

that has dealt with an IVA with self-adaptors, Neff et

al. reported that an agent performing self-adaptors

(repetitive quick motion with a combination of

scratching its face and head, touching its body, and

rubbing its head, etc.), was perceived as having low

emotional stability. Although showing emotional

unstableness might not be appropriate in some social

interactions, their finding suggests the importance of

self-adaptors in conveying a personality of an agent

(Neff, 2011).

However, self-adaptors are not always the sign of

emotional unstableness or stress. Blacking states self-

adaptors also occur in casual conversations, where

conversants are very relaxed (Blacking, 1977).

Chartrand and Bargh

have shown that mimicry of

particular types of self-adaptors (i.e., foot tapping and

face scratching) can cause the mimicked person to

perceive an interaction as more positive, and may lead

to form rapport between the conversants

(Chartrand,

1999).

We focus on these “relaxed” self-adaptors

performed in a casual conversation in this study. If

those relaxed self-adaptors occur with a conversant

Koda, T., Ishioh, T., Watanabe, T. and Kubo, Y.

Analysis of Gender-specific Self-adaptors and Their Effects on Agent’s Impressions.

DOI: 10.5220/0005660800190026

In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence (ICAART 2016) - Volume 1, pages 19-26

ISBN: 978-989-758-172-4

Copyright

c

2016 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

19

that one feels friendliness, one can be induced to feel

friendliness toward a conversant that displays self-

adaptors. We apply this to the case of agent

conversant, and hypothesize that users can be induced

to feel friendliness toward the agent by adding self-

adaptors to the body motions of an agent, and

conducted two experiments.

The first experiment evaluated continuous

interactions between an agent that exhibits self-

adaptors and without (Koda, 2014a). The results

showed agents that exhibited relaxed self-adaptors

were more likely to prevent any deterioration in the

perceived friendliness of the agents than agents that

have no self-adaptors. In addition, people with higher

social skills harbour a higher perceived friendliness

with agents that exhibited relaxed self-adaptors than

people with lower social skills. Thus, we expect that

it would be possible to improve humanness and

friendliness of agents by implementing self-adaptors

in them. The second experiment evaluated

interactions with agents that exhibit either relaxed

self-adaptors or stressful self-adaptors in a desert

survival task. The result suggests the need to tailor

non-verbal behaviour of virtual agents according to

conversational contents between an agent and a

human (Koda, 2014b).

This paper reports a preliminary result of our

consecutive experiment that deals with gender issues.

Our two previous experiments used a female agent

only and did not consider the effects of appearance of

the agent’s gender. Moreover, as some self-adaptors

are gender-specific (Hall, 1984), i.e., “crossing arms”

self-adaptors are more frequently found in males, and

“covering mouth” self-adaptors are mostly found in

Japanese females, we need to consider gender of the

agent, gender-specific self-adaptors, and gender of

participants. As Cassell points out in (Cassell, 2002),

considering gender effect is essential for successful

and comfortable human-computer interaction, so as

for human-agent interaction.

We evaluate the impression of the agents with

male/female appearance and masculine/feminine

self-adaptors in this experiment. We hypothesize that

“when the participant’s gender, agent’s gender, and

gender of the gender-specific self-adaptors are

consistent, participants feel higher naturalness and

have better impression toward the agent than any

other combinations”.

2 VIDEO ANALYSIS OF

SELF-ADAPTORS AND

IMPLEMENTATION OF AGENT

ANIMATION

2.1 Video Analysis of Self-adaptors

We conducted a pre-experiment in order to examine

when and what kind of self-adaptors are performed,

and whether/what kind of gender-specific self-

adaptors are found during a casual conversation

between friends in a Japanese university. We invited

ten pairs (5 male pairs and 5 female pairs) who are

friends for more than three years (they are university

students who study together) to record their free

conversation for 20 minutes.

The video analysis were made in terms of the

body parts touched, frequency of each self-adaptors,

and number of participants who performed each self-

adaptors during the conversation for all 20

participants. The results of the video analysis is

shown in Table 1 and 2. Table 1 shows the top five

types of self-adaptors performed most frequently and

most participants (how and which body parts were

touched, how many times for each self-adaptor, and

by how many people for each self-adaptor) by the

male participants and Table 2 by the female

participants. We identified the following gender-

specific self-adaptors in Japanese university students.

There are three types of self-adaptors occurred most

frequently in male participants: “touching nose”,

“touching chin,” and “scratching head.” We call these

self-adaptors as “masculine self-adaptors” hereafter.

The most frequent self-adaptors performed by female

participants are “touching nose”, “stroking hair“, and

“touching mouth (covering mouth)”. We call these

self-adaptors as “feminine self-adaptors” hereafter.

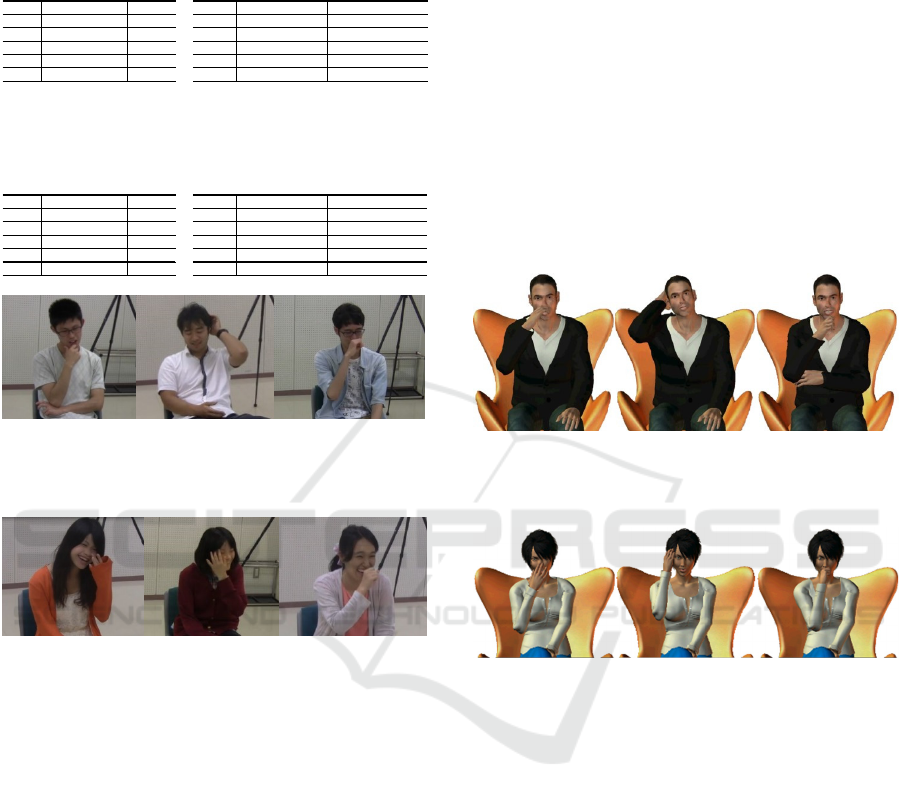

Figure 1 shows typical masculine self-adaptors seen

in the video recordings performed by Japanese male

students, and Figure 2 shows those by Japanese

female students.

We implement those masculine/feminine self-

adaptors to our conversational agents for the

experiment. In terms of the timing of self-adaptors,

50% occurred at the beginning of the utterances in the

video recordings.

ICAART 2016 - 8th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

20

Table 1: Self-adaptors performed by male participants in

video recordings (left: number of times, right: number of

people).

Table 2: Self-adaptors performed by female participants in

video recordings (left: number of times, right: number of

people).

Figure 1: Male participants perform three masculine self-

adaptors (from left: “touching chin,” “scratching head,” and

“touching nose”.

Figure 2: Female participants perform three feminine self-

adaptors (from left: “touching nose”, “stroking hair“, and

“touching lips (covering mouth)”.

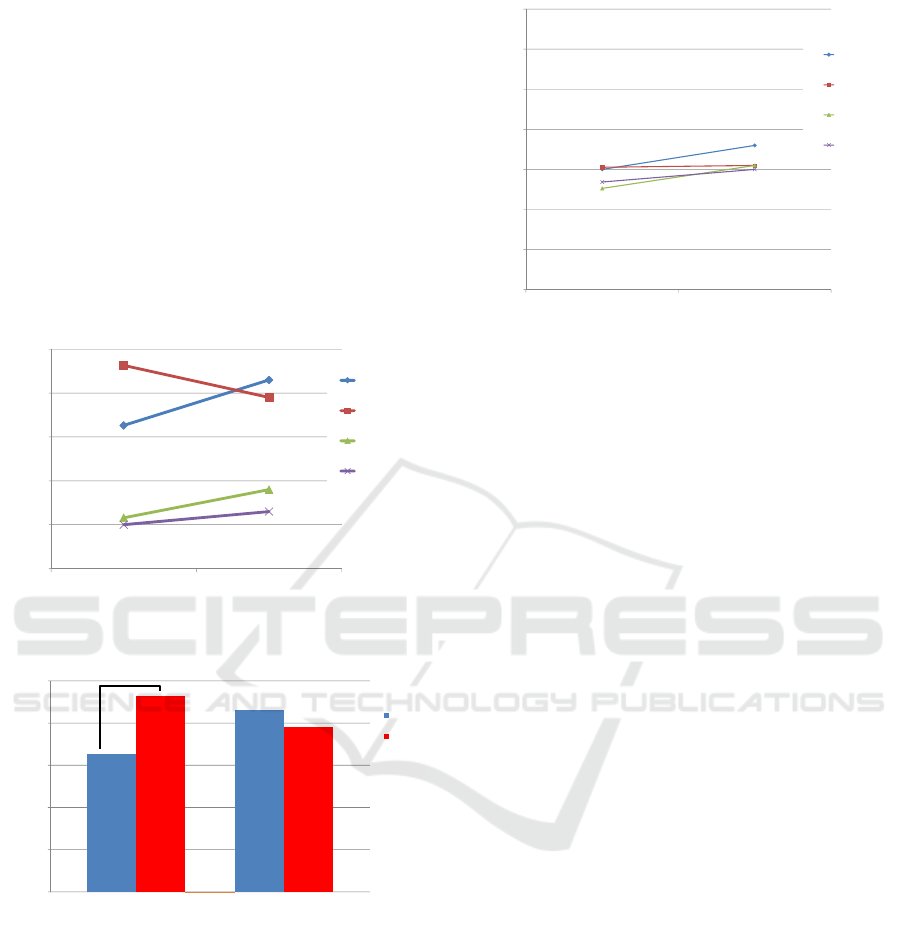

2.2 Agent Character and Animation

Implementation

The agent characters (male and female) and

animation of the six types of self-adaptors were

created using Poser

(http://poser.smithmicro.com/poser.html). Figure 3

and 4 show the agents carrying out the three

masculine self-adaptors and three feminine self-

adaptors respectively. We created the following four

types of animations in order to examine the

combination of gender of the character and self-

adaptors; “male agent performs masculine self-

adaptors”, “male agent performs feminine self-

adaptors”, “female agent performs masculine self-

adaptors”, “female agent performs feminine self-

adaptors.”

We found no literature that explicitly described

the form of the movement (e.g., how the nose has

been touched, in which way, by which part of the

hand etc.), we mimicked the form of the movements

of the participants in the video recordings. We adjust

the timing of the animation of self-adaptors at the

beginning of the agent’s utterances as found in the

video recordings.

Besides these self-adaptors, we created

animations of the agent making gestures of “greeting”

and “placing its hand against its chest.” These

gestures were carried out by the agent at appropriate

times in accordance to the content of the conversation

regardless of experimental conditions in order not to

let self-adaptors stand out during a conversation with

the agent.

Figure 3: Male agent performs three masculine self-

adaptors (from left: “touching chin,” “scratching head,” and

“touching nose”.

Figure 4: Female agent performs three feminine self-

adaptors (from left: “touching nose”, “stroking hair“, and

“touching lips (covering mouth)”.

3 EXPERIMENT

3.1 Experimental System

The agent’s conversation system was developed in

C++ using Microsoft Visual Studio 2008. The agent’s

voice was synthesized in a woman’s voice using the

Japanese voice synthesis package AITalk

(http://www.ai-j.jp/). Conversation scenarios,

composed of questions from the agent and response

choices, were created beforehand, and animation of

the agent that reflected the conversational scenario

was created. By connecting animated sequences in

accordance of the content of the user’s responses, the

system realized a pseudo-conversation with the user.

The conversation system had two states. The first

Male participants n=587 Male participants n=10

Order Self-adaptor Frequency Order Self-adaptor Number of participants

1 touching nose 61 1 scratching head 9

2 toucing chin 55 2 touching nose 9

3 scratching head 35 3 scratching forehead 6

4 touching cheek 30 4 touching chin 6

5 scratching nose 29 5 scratching neck 6

Female participants n=617 Female participants n=10

Order Self-adapator Frequency Order Self-adaptor Number of participants

1 Touching nose 66 1 Touching mouth 8

2 Stroking hair 49 2 Touching nose 7

3 Touhcing sleeves 40 3 Stroking hair 6

4 Toucing mouth 38 4 Touching bangs 6

5 Touching fingers 31 5 Scratching nose 6

Analysis of Gender-specific Self-adaptors and Their Effects on Agent’s Impressions

21

state was the agent speech state, in which an animated

sequence of the agent uttering speech and asking

questions to the user was shown. The other state was

the standby for user selection state, in which the user

chose a response from options displayed on the screen

above the agent. In response to the user’s response

input from a keyboard, animated agent movie that

followed the conversation scenario was played back

in the speech state.

3.2 Experimental Procedure

The interactions with the agents were presented as

pseudo conversations as follows: 1) the agent always

asks a question to the participant. 2) Possible answers

were displayed on the screen and the participant

selects one answer from the selection from a

keyboard. 3) The agent makes remarks based on the

user’s answer and asks the next question. The

contents of the conversations were casual (the route

to school, residential area, and favourite food, etc.).

The reason we adopted the pseudo-conversation

method was to eliminate the effect of the accuracy of

speech recognition of the users’ spoken answers,

which would otherwise be used, on the participants’

impression of the agent.

The participants in the experiment were 29

Japanese undergraduate students (19 male and 10

female), aged 20-23 years, who did not participate in

the video recording pre-experiment. The

experimental is conducted as 3 x 2 factorial design.

The experimental conditions are participants’ gender

(male/female), agent’s gender (male/female), gender

of self-adaptor (male/female). Each participant

interacted with all four types of agents (male agent

performing masculine self-adaptors, male agent

performing feminine self-adaptors, female agent

performing masculine self-adaptors, female agent

performing feminine self-adaptors) randomly

assigned to them. Thus, there are four interactions

with different combination of the agent and self-

adaptor for each participant. The conversational

topics are different for each interaction and the topics

are randomized. Each agent performed three all

gender specific self-adaptors in any interaction.

After each interaction, the participants rated their

impressions on the agent using a semantic differential

method on a scale from 1 to 6. A total of 27 pairs of

adjectives, consisting of the 20 pairs from the

Adjective Check List (ACL) for Interpersonal

Cognition for Japanese (Hayashi, 1982) and seven

original pairs (concerning the agent’s “humanness,”

“naturalness,” “annoyingness”, and “masculinity”

etc.), were used for evaluation. The list of adjectives

is shown in Table 3 in Section 4. At the end of the

experiment, a post-experiment survey was conducted

in order to evaluate the participants’ subjective

impression of overall qualities of the agents, such as

the naturalness of their movements and synthesized

voice.

4 RESULTS

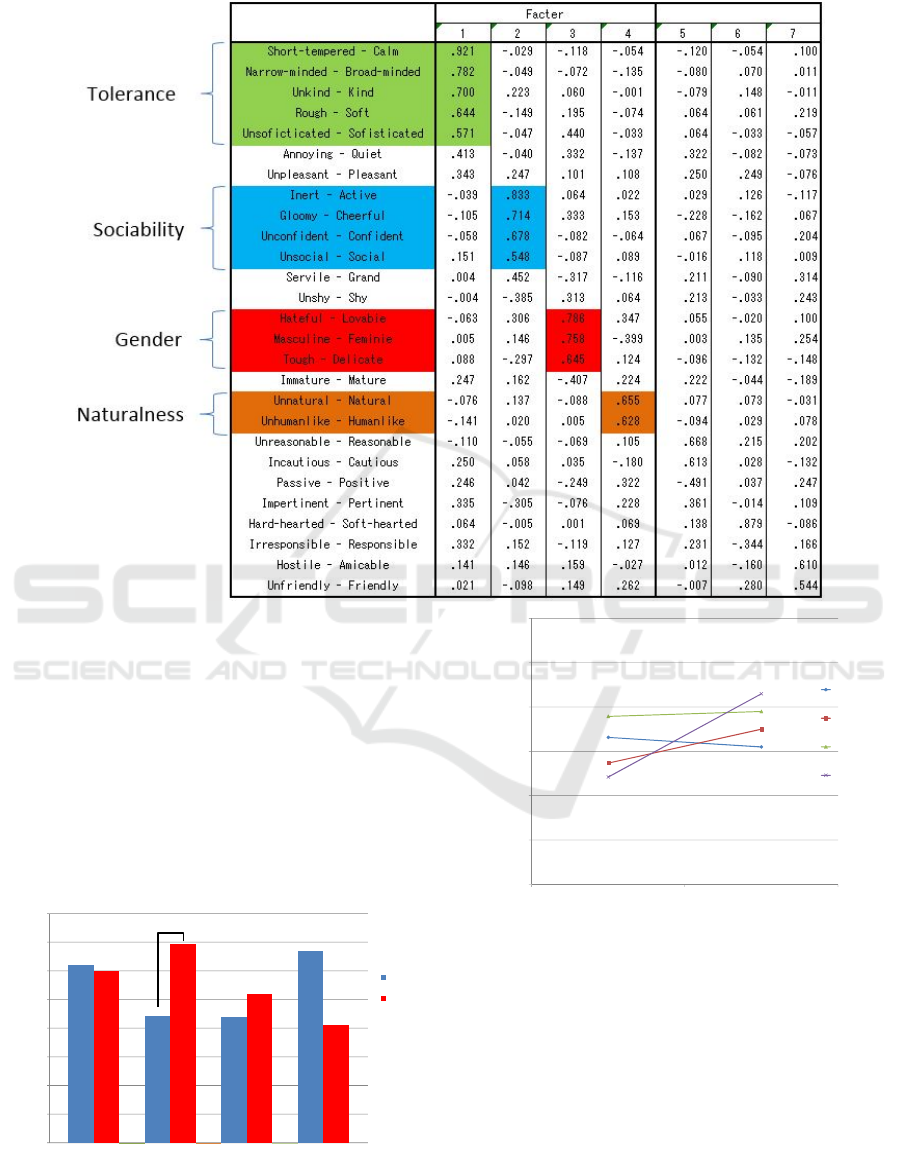

4.1 Results of Factorial Analysis

Factor analysis (FA) was conducted on the agent’s

impression ratings obtained from the experiment in

order to extract the factors that composes our

interpersonal impressions toward the agents. The

results of FA using the principal factor method

extracted four factors (shown in Table 3). The First

factor is named as “Tolerance factor (composed of

adjectives such as calm, broad-minded, kind, soft, and

sophisticated), the second as “Sociability factor”

(composed of adjectives such as active, cheerful,

confident, and social), the third as “Gender factor”

(composed of adjectives such as lovable, feminine,

and delicate), and the forth as “Naturalness factor”

(composed of adjectives such as natural and

humanlike).

Cronbach's coefficients alpha for the factors are

0.84 for “Tolerance factor”, 0.79 for “Sociability

factor”, 0.67 for “Gender factor”, and 0.62 for

“Naturalness factor”, which show high enough

internal consistency of the extracted factors. The

result of the factorial analysis indicates when the

participants perceive the agents interpersonally and

rate their impressions, these four factors have large

effects. Thus we will use the factors and factorial

scores for later analysis to evaluate the gender effects.

4.2 Analysis of Tolerance Factor and

Sociability Factor

We performed three-way ANOVA (repeated

measures) with factors “participant gender”, “agent

gender”, and “gender of self-adaptor”. The dependent

variables are total factorial score of each factor.

The result showed there are no main effects of

participants’ gender, agent’s gender, and gender of

self-adaptor on “Tolerance factor” and “Sociability

factor”. There are significant second-order

interactions in the “Tolerance factor” (p<0.05)

between participants’ gender and agents’ gender.

Figure 5 shows the tolerance factor score of each

condition. The male participants rated the female

agent performing feminine self-adaptors significantly

ICAART 2016 - 8th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

22

Table 3: Four factors and adjectives for interpersonal impressions.

higher than the same agent performing masculine

self-adaptors (F: 4.58, p<0.05). While the female

participants showed tendency for higher rating to the

female agent performing masculine self-adaptors (F:

2.55, p=0.122). There are no difference in the

tolerance factors when the participants evaluated the

male agent. While to the case of female agent, the

tolerance scores were higher when the female agent

performs different gender’s self-adaptors from the

participants’ gender. There are no significant main

effects nor second-order interactions found in the

“Sociability factor” (shown in Figure 6).

Figure 5: Tolerance factor score of four conditions

compared by participants’ gender.

Figure 6: Sociability factor score of four conditions.

4.3 Analysis of Gender Factor

We performed three-way ANOVA for total factorial

scores of gender factor. Figure 7 shows gender factor

scores of four conditions. The main effect of agent’s

gender on gender factor is found (p<=0.01).

Significant second-order interactions are not seen in

gender factor. These results mean the agents’

appearance made significant differences in

impression of gender. The male agent were perceived

as more masculine than the female agent regardless

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

Male

Female

Tolerance Factor

Self-adaptor

Male Agent Female Agent Male Agent Female Agent

Male Participant Male Participant Female Participant Female Participant

*

*: p<0.05

Hight

←

→

Low

n=29

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

Male participant Female participant

Male agent

Male adaptor

Male agent

Female adaptor

Female agent

Male adaptor

Female agent

Female adaptor

Sociability

Factor

Hight

←→

Low

Analysis of Gender-specific Self-adaptors and Their Effects on Agent’s Impressions

23

of the gender of self-adaptors, and the female agent

were perceived as more feminine than the male agent

regardless of the gender of the self-adaptors by both

gender of participants.

However, when we focus on the gender factor

score of the female agent, a significant difference in

participants’ gender was found. As shows in Figure 8,

in the case of female agent, the male participants

perceived significant higher femininity to the female

agent performing feminine self-adaptor (F: 4.88,

p<0.05) than the same agent performing masculine

ones. While the female participants showed no

difference in the gender scores of the same agent

conditions.

Figure 7: Gender factor scores of four conditions compared

by participants’ gender.

Figure 8: Gender factor scores of female agent conditions

compared by participants’ gender.

4.4 Analysis of Naturalness Factor

We performed three-way ANOVA for total factorial

scores of “Naturalness factor”. Figure 9 shows

naturalness factor scores of four conditions. There are

no significant main effects nor second-order

interactions found in the naturalness factor. This

means the participants perceived agents with all

conditions as equally natural.

Figure 9: Naturalness factor score of four conditions.

5 DISCUSSION AND FUTURE

DIRECTIONS

The above results showed we did not find

deterioration in the perceived naturalness of agents

when the agents’ appearance and gender of self-

adaptors don’t match. In the case of the female agent,

there are interactions between the participants’

gender and gender of self-adaptors in the tolerance

factor. Specifically, the female participants had lower

impression on the feminine self-adaptors performed

by the female agent. Thus, our hypothesis “when the

participant’s gender, agent’s gender, and gender of

the gender-specific self-adaptors are consistent,

participants feel higher naturalness and have better

impression toward the agent than any other

combinations” was not fully supported. We will

discuss why the hypothesis was not supported below.

When the participants evaluate the impression of

the agents used in the experiment, the four factors

forms the overall impression of the agent, namely,

tolerance, sociability, gender, and naturalness. The

analysis of gender factor showed the participants of

both gender correctly perceived the gender of the

agent. Only male participants perceived the feminine

self-adaptors performed by the female agent as most

feminine, while such correct perception did not occur

in the case of the female participants, nor of the male

agent, and the masculine self-adaptors. On the other

hand, all agents in four conditions are perceived as

equally natural even when the gender of the agent and

the gender of self-adaptors don’t match. In terms of

perceived tolerance, the female agent’s performing

the feminine self-adaptors resulted in opposite

impressions between the male and female participants.

The male participants perceived the female agent

performing feminine self-adaptors as most tolerant,

8

9

10

11

12

13

Male participant Female participant

Female agent

Male adaptor

Female agent

Female adaptor

Male agent

Male adaptor

Male agent

Female adptor

Gender Factor

Female ←

→ Male

n=29

8

9

10

11

12

13

Male

Female

Self-adaptor

Female agent Female agent

Male participant Female participant

Gender Factor

Female ←

→ Male

*

*:p<0.05

n=29

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

Male participant Female participant

Male agent

Male adaptor

Male agent

Female adaptor

Female agent

Male adaptor

Female agent

Female adaptor

Naturalness

Factor

High

←→

Low

n=29

ICAART 2016 - 8th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

24

while the female participants rated the same condition

as least tolerant in all conditions.

The results suggest interesting gender differences

in perceiving the feminine self-adaptors. The

Japanese male participants are in favour of the

feminine self-adaptors, while the Japanese female

participants have rigorous impression on them when

they are performed by the female agent, without

noticing the difference as all conditions are rated as

equally natural. This suggest there is a dichotomy

between participants’ gender in the perception of

combination of self-adaptor and agent’s gender.

This research is still at a starting phase, thus has

several limitations. Firstly, we need to conduct more

fine grained study on the self-adaptor in human-

human interactions. Extraction of self-adaptors was

made from the video recordings of only 20

participants, who are undergraduate students in Japan.

The evaluations of self-adaptor performing agents

were made by 29 Japanese undergraduate students

(different subjects from those who were videotaped).

Given the enormous inter-subjective variability in

gesture use, we need to conduct close observations on

the form and movements of self-adaptors with larger

samples with wider age range and cultures.

Secondly, although we compared only

masculine/feminine self-adaptors in this experiment,

we need to compare impressions with non-self-

adaptor condition in order to evaluate the masculinity

and feminity of the self-adaptors solely.

Thirdly, future work should also consider cultural

diversity in expressing and perceiving self-adaptors.

There are culturally-defined preferences in bodily

expressions (Johnson, 2004, Rehm, 2007, Rehm,

2008, Aylett, 2009) and in facial expressions (Koda,

2009, Rehm, 2010), and allowance level of

expressing non-verbal behaviour are culture-

dependant. Japanese male tend to perform self-

adaptors around their nose and chin more frequently

than other cultures by observation, and Japanese

female tend to cover their mouth while talking, which

is considered as typical Japanese female self-adaptor.

We will investigate culture specific self-adaptors

from video recordings of human-human interactions

from other cultures. Furthermore, we will implement

them with agents, and conduct a cross-cultural

evaluation study.

6 CONCLUSIONS

Our evaluation of the interactions between the agents

that exhibit self-adaptors typically exhibited by

Japanese male and female indicated that there is a

dichotomy on the impression on the agent between

participants’ gender. Japanese male participants

showed more favourable impressions on agents that

display feminine self-adaptors than masculine ones

performed by the female agent, while Japanese

female participants showed rigorous impressions

toward feminine self-adaptors. These results implies

the importance of considering the use of self-adaptors

and gender in successful human-agent interactions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research is partially supported by a Grant-in-Aid

for Scientific Research (C) 26330236) (2014-2016)

from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

REFERENCES

Argyle, M., 1988. Bodily communication. Taylor & Francis.

Aylett, R., Vannini, N., Andre, E., Paiva, A., Enz, S., Hall,

L., 2009. But that was in another country: agents and

intercultural empathy. In Proc. of International

Conference on Autonomous Agents and Multiagent

Systems, Vol. 1. pp. 329-336.

Blacking,j.,(ed)., 1977. The Anthropology of the Body,

Academic Press.

Caso, L., Maricchiolo, F., Bonaiuto, M., Vrij, A., and Mann.

S. 2006. The Impact of Deception and Suspicion on

Different Hand Movements. Journal of Nonverbal

Behavior, 30(1), pp. 1-19.

Cassell, J., 2002. Genderizing HCI. In J. Jacko and A. Sears

(eds.), The Handbook of Human-Computer Interaction.

pp. 402-41, Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Chartrand, T. L., and Bargh, J. A. 1999. The chameleon

effect: The perception–behavior link and social

interaction. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology,

76, pp. 893–910.

Ekman, P., Friesen, W.V., 1972. Hand movements. In

Journal of Communication 22, pp. 353-374.

Ekman P., 1980. Three classes of nonverbal behavior. In

Aspects of Nonverbal Communication. Swets and

Zeitlinger.

Hall, J. A., 1984. Nonverbal sex differences:

Communication accuracy and expressive style.

Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Hayashi, T., 1982. The Measurement of Individual

Differences in Interpersonal Cognitive Structure. In

Experimental Social Psychology 22, pp. 1-9 (in

Japanese).

Johnson, W., Marsella, S., Mote, N., Viljhalmsson, H.,

Narayanan, S., Choi, S., 2004. Tactical language

training system: Supporting the rapid acquisition of

foreign language and cultural skills. In Proc. of

InSTIL/ICALLNLP and Speech Technologies in

Advanced Language Learning Systems.

Analysis of Gender-specific Self-adaptors and Their Effects on Agent’s Impressions

25

Koda, T., Ishida. T., Rehm, M., and Andre, E., 2009. Avatar

culture: cross-cultural evaluations of avatar facial

expressions. In Journal of AI & Society, Vol.24, No.3,

pp.237-250. Springer London.

Koda, T. and Higashino, H., 2014a. Importance of

Considering User's Social Skills in Human-agent

Interactions. In Proc. of ICAART2014, pp. 115-122.

Koda, T., and Mori, Y., 2014b. Effects of an agent's

displaying self-adaptors during a serious conversation.

In: T. Bickmore et al. (Eds.): IVA 2014, LNAI 8637, pp.

240–249, Springer-Verlag.

Neff, M., Toothman, N., Bowmani, R., Fox Tree, J. E.,

Walker, M., 2011. Don’t Scratch! Self-adaptors Reflect

Emotional Stability. In Vilhjalmsson, H. H. et al.

(Eds.): IVA 2011, LNAI 6895, pp. 398-411. Springer-

Verlag.

Rehm, M., Andre, E., Bee, N., Endrass, B., Wissner, M.,

Nakano, Y., Nishida,T., Huang, H., 2007. The cube-g

approach -coaching culture-specific nonverbal

behavior by virtual agents. In Organizing and learning

through gaming and simulation: proc. of Isaga 2007 p.

313.

Rehm, M., Nakano, Y., Andre, E., Nishida, T., 2008.

Culture-specific first meeting encounters between

virtual agents. In Proc. of IVA2008, pp. 223-236.

Springer-Verlag.

Rehm, M., Nakano, Y., Koda, T., and Winschiers-

Theophilus, H., 2010. Culturally Aware Agent

Communications. In Marielba Zacharias, Jose Valente

de Oliveira (eds): Human-Computer Interaction: The

Agency Perspective. Studies in Computational

Intelligence, Vol. 396, pp. 411-436. Springer.

Waxer, P., 1988. Nonverbal cues for anxiety: An

examination of emotional leakage. In Journal of

Abnormal Psychology, 86(3), pp. 306-314.

ICAART 2016 - 8th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

26