On the Development of Serious Games in the Health Sector

A Case Study of a Serious Game Tool to Improve Life Management Skills

in the Young

Tanja Korhonen

1,2

and Raija Halonen

2

1

Information Systems, Kajaani University of Applied Sciences, Kajaani, Finland

2

Faculty of Information Technology and Electrical Engineering, University of Oulu, Oulu, Finland

Keywords: Serious Game, Health Game, Visual Novel, Life Management Skills.

Abstract: The current research focuses on serious games (SG) in the healthcare sector. The objective was to identify the

key phases in the design and development of SG and to study how serious game design takes into account

affective computing. The case study describes the development of Game of My Life (GoML), a visual novel

aiming to support the life management skills of adolescents. The game was developed in two phases using

iterative agile methods in cooperation with different stakeholders. The evaluation indicates that GoML can be

used as an effective discussion tool for professionals and patients in nursing and youth work. The results

support our existing knowledge of SG development and reveal that SG design takes into account affective

computing by nature: game design deliberately influences emotions in order to engage the players.

1 INTRODUCTION

Games can work as motivators and help to change

players’ behaviour (Baranowski et al., 2013; Ryan et

al., 2006). Digital games create a structured conflict

and provide an entertaining process for players to

resolve this conflict (Fullerton, 2014). Video games

allow the possibility not just to tell a story but also to

allow a player to live it (Rigby and Ryan, 2011).

Our research goal was to identify the key phases

of the design and development of serious games (SG)

with respect to affective computing. The research

goal was met with the help of two questions: What are

the key phases when designing and developing SG?

How does SG design take into account affective

computing?

Various definitions of serious games exist, but it

is commonly stated that SG refers to using games and

game technology for purposes other than pure

entertainment (Djaouti et al., 2011; Susi et al., 2007;

Zyda, 2005).

Serious games in healthcare may be one strategy

for coping with the increasing challenges of ageing

populations and chronic diseases (Arnab et al., 2013).

Related to this, Kemppainen, Korhonen and Ravelin

(2014) point out that health games can provide a new

method for maintaining and developing the health

capability of different age groups. An important goal

of health games is to provide new kinds of models for

self-help or rehabilitation (Kemppainen et al., 2014).

Affective computing (AC) aims to close the

communicative gap between human emotions and

computers by applying systems that recognise and

adapt to the user´s affective states. Computer games

usually provide very dynamic forms of human–

computer interaction since they are designed to offer

affective experiences that are influenced by player

feedback (Iovane et al., 2012; Yannakakis and

Togelius, 2011).

This paper presents the development of Game of

My Life (GoML) as a case study and is organised into

five major sections. Following this introduction, the

next section reviews the related work on serious

games. Section three presents the design and

development of GoML. Section four offers a

discussion, and section five provides conclusions.

2 RELATED WORK

This chapter presents the earlier knowledge related to

the current study. First, affective computing and

games are explained, followed by aspects of game

Korhonen, T. and Halonen, R.

On the Development of Serious Games in the Health Sector - A Case Study of a Serious Game Tool to Improve Life Management Skills in the Young.

DOI: 10.5220/0006331001350142

In Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS 2017) - Volume 3, pages 135-142

ISBN: 978-989-758-249-3

Copyright © 2017 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

135

design and serious games in healthcare. Finally, the

visual novel is introduced.

2.1 Affective Computing and Games

Computer games provide a valuable research setting

for human–computer interaction research,

particularly with respect to their design, interfaces

and design processes (Yannakakis and Togelius,

2011). As games often offer emotional experiences,

they are a good example of affective computing

(Yannakakis and Togelius, 2011). In 1995, Picard

defined affective computing as “computing that

relates to, arises from, and deliberately influences

emotion” (2010, p. 11). Yannakakis, Isbister, Paiva

and Karpouzis (2014) suggest that computer games

can best realise affective interaction. The rich content

of games, consisting of music, sound effects, audio,

virtual graphics and game mechanics, provides

obvious triggers for raising the emotions of players

(Yannakakis et al., 2014).

Research on player motivation attempts to

establish the psychological needs that games satisfy

and how different games fulfil these needs. This

provides information about both the positive and

negative experiences within games (Rigby and Ryan,

2011).

Malone and Lepper (1987) identified four major

factors that make a learning environment such as a

gaming activity intrinsically motivating: challenge,

curiosity, control and fantasy. These individual

factors motivate a player when playing alone, while

interpersonal factors such as cooperation,

competition and recognition motivate a player when

interacting with other players (Malone and Lepper,

1987).

The Player Experience of Need Satisfaction

(PENS) model details the satisfactions that hook

players to games. This model is based on the fact that

video games are considered most engaging when they

satisfy specific intrinsic needs: competence,

autonomy and relatedness. Competence refers to our

desire to grow abilities and gain mastery of new

situations and challenges. Digital games easily

provide highly engaging experiences in rich virtual

worlds, which brings immediacy and can satisfy

motivational needs such as competence and mastery.

Autonomy refers to our desire to take actions based on

our own decisions and not to be controlled by others.

There is a certain consistency in games: once a player

learns the rules, the outcome will consistently reflect

the player’s actions and expectations. Relatedness

reflects our need to have meaningful connections with

others (Rigby and Ryan, 2011). Density refers to the

ability of games to deliver competence and the other

needs at a high tempo and with a well-built feedback

system.

2.2 Game Design Aspects

Designing digital games involves psychological

aspects (Rigby and Ryan, 2011) as well as mechanical

and artistic aspects (Fullerton, 2014). According to

Rollings and Adams (2003), game design is a process

that includes imagining a game, defining how it

works, describing its elements and transmitting all

this information to the game development team. A

common element in digital game design is designing

systems of actions and outcomes where the game

responds easily to a player’s input (Salen and

Zimmerman, 2004).

The process of video game design involves

designing the content and rules in the pre-production

stage and designing the gameplay, environment,

storyline and characters in the production stage

(Bethke, 2003; Fullerton, 2014). Adams (2013)

divides the game design process into three parts: the

concept stage, which is performed first; the

elaboration stage, where most of the design details

are added and refined; and, finally, the tuning stage,

which involves polishing the game.

2.3 Serious Games in Healthcare

Social security systems and healthcare providers

differ among various countries and on a global scale,

with each market area having its own methods for

facilitating a healthy lifestyle (Kaleva et al., 2013).

There are many different stakeholders in the health

game market: hospitals, clinics, private practice

physicians, governments, corporations, other

organisations and individual consumers (Susi et al.,

2007).

Braad, Folkerts and Jonker (2013), Friess, Kolas

and Knoch (2014) and Deen, Heynen, Schouten, van

der Helm and Korebrits (2014) have all used similar

processes in serious game development in the health

sector. These processes all include a strong research

and analysis phase at the beginning. Involving

different stakeholders is also essential. An iterative

development process (or prototyping) is used, along

with user-group testing and an evaluation or

validation phase at the close of the game development

process.

Supporting players’ motivation and enhancing

behaviour change are key points in health game

design (Rigby and Ryan, 2011). It is essential to use

game elements like surprise and simulation to engage

players and enable immersion (Adams, 2013). In

addition, developing a health game needs a

multidisciplinary team to work successfully together

(Kemppainen et al., 2014). Brox, Fernandez-Luque

and Tollefsen (2011) suggest that it is important to:

ICEIS 2017 - 19th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

136

1. define both the target group and the main

objective;

2. design a game accordingly, using sound

game design principles;

3. utilise design elements to enhance learning

and persuasion;

4. collaborate with health professionals from an

early design stage;

5. involve patients, especially to improve

usability.

Iterative design is a play-based design model. It

emphasises playtesting and prototyping, which

allows players to be part of the game design. In

iterative design, a rough model of the game—a rapid,

interactive prototype—is created as early as possible.

This may have placeholder graphics, but it can be

played and evaluated. The user comments and

evaluations influence the game’s further design

(Salen and Zimmermann, 2004).

When designing serious games in healthcare, the

target group should be taken into account during the

development process (Brox et al., 2011; Braad et al.,

2013; Friess et al., 2014; Deen et al., 2014).

Professional knowledge is an essential part of the

development (Merry et al., 2012).

It is essential to include an assessment of serious

games’ usefulness and effectiveness in the

development process (Graafland et al., 2014).

Desurvire, Caplan and Toth (2004) outline a set of

design heuristics, which are guidelines that serve as

an evaluation tool specific to video games. According

to their definitions, the Heuristics for Evaluating

Playability (HEP) categories include: evaluating

game play; game story—plot and character

development; game mechanics; and game usability.

HEP is recommended for use in the early design

phase (Desurvire et al., 2004).

2.4 Visual Novel

A visual novel is a narrative-based digital medium

that players can guide by making decisions, thus

altering the outcomes. According to Lu (2013), it

enables a collective participation experience, even

though it is usually played alone. A visual novel is

more like a role-playing game than a simulation

(Cavallaro, 2010; Lu, 2013).

A visual novel consists of a soundscape, static

graphics or animations, immersive storytelling and

interactive decision-making moments that allow the

player to decide how the visual novel progresses. The

pace of the game’s progress is slow, and this gives the

players time to process their thoughts during the

gameplay. The genre is dependent on narrative and

dialogue. An engaging video game narrative enables

a personal experience for the players and creates their

affection for the characters (Cavallaro, 2010; Gabriel

and Young, 2011; Lu, Baranowski, Thompson and

Buday, 2012; Lu, 2013).

3 CASE STUDY: DEVELOPMENT

OF GAME OF MY LIFE

Game of My Life (GoML) is an online game in a visual

novel style that aims to support the life management

skills of adolescents aged 16–19 years.

3.1 User Needs and Analysis

The need for the game arose from youth psychiatry

experts who wanted new tools for approaching their

young (16–19 years) patients. The main objective was

to create a game that could be used as a tool in

conversations between experts and patients regarding

life management issues. The experts suggested that

the game be based on the Finnish theoretical

framework by Ylitalo (2011). This framework

describes a role map of a young person in the process

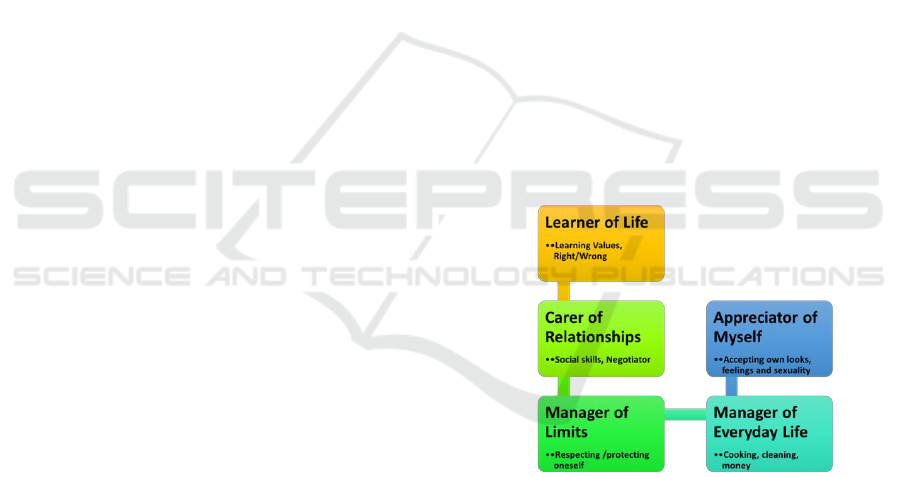

of becoming independent. The role map (Fig. 1)

includes five motivation roles, with subcategories for

goal-oriented roles and action roles.

Figure 1: Role map of a young person in the process of

becoming independent.

The game development process began by

searching for existing games in the market. The most

promising at the time (2012) was a PC game called

SPARX, which had been developed in New Zealand

for the treatment of mildly depressed adolescents and

used as a stand-alone self-help intervention. After

testing, it was decided that this game was not the kind

of tool that the youth psychiatry experts were looking

for to help in discussion with young patients.

The next step was to gather more information

about the life management skills of adolescents from

their own point of view, particularly regarding

On the Development of Serious Games in the Health Sector - A Case Study of a Serious Game Tool to Improve Life Management Skills in

the Young

137

problems related to mental health and substance

abuse. This was done by qualitative research into six

young persons who participated in individual semi-

structured theme interviews. The research focused on

how these young people understood life management

and what challenges they had with it. It also gathered

their expectations for a game supporting life

management. The results showed that the young

people had difficulty understanding the term life

management skills but found it easier to understand

when it was called managing your everyday life. The

participants hoped that the developed game would

provide information on substance abuse, as well as on

the use of time and money.

These activities formed an analysis phase that

consisted of:

1. Cooperation with health professionals:

carrying out a preliminary requirements

analysis that defined the target group and

the main objective of the serious game

being developed.

2. Quick market research into similar

products.

3. Testing and reporting on the most

significant similar products.

4. Involving end users in order to find the

most problematic aspects that needed to

be covered in the game.

3.2 Game Concept

After understanding the user needs, the focus moved

to user–computer interaction and the game concept

design. It was decided that GoML should be a

network game, playable in a prototype phase on the

most used browsers and Android tablets. After a

literature search, a visual novel was selected as the

game genre. A visual novel can evoke feelings in

players, thus making it the powerful tool that the

experts were looking for. The narrative of the visual

novel had three characters (two male, one female), all

with three different storylines relating to their school,

home and free time. Each of these was based on the

“role map of a young person in the process of

becoming independent” (Fig. 1). To get a feeling of

interactive decision making, decision paths were

planned according to the storylines, with players

guiding the narrative by choosing from multiple

choices with a mouse (PC) or by tapping their finger

(tablet). It was agreed that, in order to provide

additional information, there would be external links

at the end of each storyline.

Restrictions due to budget, resources and timing

meant that this was a visual novel without

soundscape, with the maximum gameplay time for

each storyline limited to 15 minutes. The graphics for

GoML were simple and static and had a cartoon look

with a user interface like a book and easy-to-use

buttons.

The above features created the game concept for

this serious game, which could then be used for

further content creation.

3.3 Content Creation for the GoML

Demo

Serious games development uses a standard game

design process to develop an immersive game. This

involves designing the game play and flow as well as

the interactive narrative and dialogue.

The development of GoML began by finding an

appropriate art style and writing the first storyline.

The first team, consisting of three game development

students (a game designer and producer, a

programmer and an artist), developed the first demo

version during 2012.

The game design began with ideating among the

team and with a nursing lecturer and her students to

get more accurate content. The nursing students

brought valuable information about patient needs to

the process. The ideas were also presented throughout

the project to several stakeholders, including youth

psychiatry experts and game development

professionals. The game design document covered

the main idea for the whole game, but it was decided

that only the “Home” level of one character could be

included in the demo version. The design of the visual

novel also included the story writing, in which themes

from the “role map of a young person in the process

of becoming independent” influenced the content.

The art style was kept simple; it was cartoonish and

used light colours that would bring a positive

atmosphere to the game.

Since the game mechanics were simple and used

a web-browser platform, the production was carried

out using Adobe Flash. This allows for quite rapid

programming, and the executables are easily

available online.

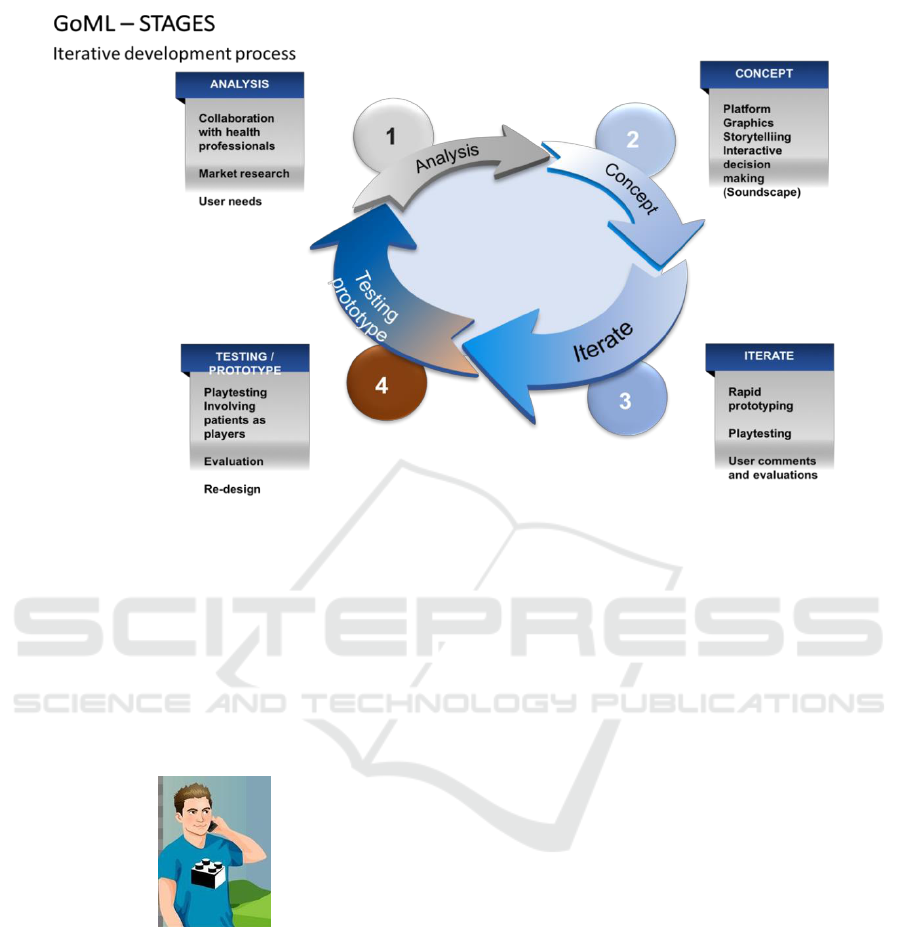

The development process, as illustrated in Figure

2, was iterative, adapting forms of agile development

such as scrum. This enabled quick prototypes to test

the ideas so that the game could be presented to

different stakeholders.

After testing and feedback, the development

continued further. In several iterative steps, the demo

of GoML was presented to youth psychiatry experts

and tested by experts and patients; it was also

evaluated by an external professional.

ICEIS 2017 - 19th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

138

Figure 2: The iterative development process with GoML stages.

3.3.1 Testing of GoML Demo

The first playable GoML demo (see Fig. 3) consisted

of one storyline and one level (“Home”) relating to

one main character. The game was tested by youth

psychiatry experts and some of their patients, but due

to the limited content of the game, the main feedback

from the testing concentrated on suggestions for

improvement.

Figure 3: Concept art for GoML demo.

A psychology student from the University of

Chicago worked with the project team by providing

information related to the visual novel. He also

carried out, as part of his studies, a more

comprehensive analysis of the SG demo using a

modified version of the Heuristics for Evaluating

Playability (HEP). This included areas of game play

game story, game mechanics and usability with

several claims in each area. Claims were assessed by

using ratings in the range of 0–3 (0 = not found in

game, 1 = poor, 2 = fair, 3 = good/excellent) and

providing a written description, if applicable. The

main result of the evaluation was that the HEP results

could be used as a good base for the next phase of the

development of GoML.

3.4 Content Creation for GoML

The second phase of the GoML development started

in 2014 with a new game development team. The

extended project team also included a nursing student

and two senior lecturers (in game development and

nursing and healthcare).

The new multidisciplinary team began by

analysing the developed demo version and gathering

the testing and evaluation results. Based on these, the

major lines of development were decided upon and

prioritised. It was understood that the available time

and budget would limit the outcomes.

A booklike graphical user interface was added to

the beginning of the game, allowing the player to

choose a character from three options and to operate

in all three storylines (levels): school, home and free

time. It was decided that the main themes of the game

would be relationships, intoxicating substances,

economic skills, mental health, and daily life

activities. The background to all the storylines was

taken from the “role map of a young person in the

process of becoming independent” (Fig. 1). During

the story, the player would be able to make decisions

by choosing from several options. At the end of each

level, the player would be able to find additional

On the Development of Serious Games in the Health Sector - A Case Study of a Serious Game Tool to Improve Life Management Skills in

the Young

139

information through external links related to the

themes of the story.

The aim of the game was to evoke new thoughts

and ways of thinking concerning daily-life decision

making and problem-solving situations. The players

would face the consequences of the choices they

made during the game.

Figure 4: New characters and colours.

The programming and tools used remained the

same, but there was a major change to the graphics in

this second phase. The art style used darker colours

and more robust characters, as presented in Figure 4.

This changed the whole atmosphere, thus making it

possible for a player to empathise with the characters.

In addition, the stories in GoML took on a new, more

realistic approach with a twist of darker shades: all

the characters had problematic backgrounds. It was

felt that the narrative’s collective assimilation would

be deeper if the players could find a means of

identification with the characters. Deeper character

descriptions were used and difficult issues in the

storyline were dealt with in order to evoke feelings in

the players, thus making the game more immersive

and effective.

3.4.1 Evaluation of GoML

The second version of GoML was tested in several

ways. It had already been under constant testing

through its availability on the website

(www.elamanipeli.com). At the end of the game,

there was a request to fill in a feedback form. This

brought only very general comments about the game.

In a qualitative study, nine young people (aged

18–22 years) who had some problems with life

management skills were interviewed after playing

GoML. According to the results, the interviewees

recognised different themes in GoML and openly

began to describe how they would act in similar

situations. GoML provoked discussion about very

difficult areas of life management such as lack of

sleep, problems at school and problems with

substance abuse. The study also showed that young

people as players tended to make decisions in the

game to see what might happen, often even making

opposite decisions from what they would do in life.

The interviewees brought up the need for more

choices that were not so obvious. The study thus

showed that GoML works as a discussion tool

between professionals and patients in nursing or

youth work: communication is easier when the

discussion concerns a third party (a game character).

The mental health professionals who participated

in the development process were provided with a

protocol on how to use GoML as a discussion tool in

their work with young people.

4 DISCUSSION

The objective was to identify the key phases in

designing and developing SG and to study how

serious game design takes into account affective

computing. Starting from serious games development

theory and based on previous literature about digital

serious games, especially visual novels and health

games, we used and further developed this knowledge

in a case study by creating a new serious game.

The game developed, GoML, can be used in

mental health work, social welfare work and youth

work as a tool for an adult and a young person to

evoke conversation and thoughts about life

management issues. It aims to help young adults to

reflect on their attitudes, thoughts and behaviour

concerning such issues.

We suggest that the analysis is one of the key

phases in designing and developing a health game. It

is essential to involve different stakeholders (such as

experts in the field) and end users (patients) as early

as possible in the game development process. A good

collaboration and an effective understanding of user

needs play a key role in finding the right triggers for

raising the emotions of players, thus leading to an

effective outcome.

In addition, a good concept for the health game

helps in the communication with different

stakeholders. An iterative development of a demo

version can be used as a proof of concept and tested

with end users. A visual novel style and well-

designed narrative can help players relate to the

characters, thus influencing their emotions.

The results support the previous work of Braad et

al. (2013), Friess et al. (2014) and Deen et al. (2014)

showing the importance of a strong research and

analysis phase at the beginning and emphasising that

a good understanding between the different

stakeholders is essential in serious game

development. The key phases of this study also follow

the guidelines for serious games development set by

Brox et al. (2011).

ICEIS 2017 - 19th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

140

We agree with Yannakakis and Togelius (2011)

who state that games can offer emotional experiences

and thus be good examples of affective computing.

We argue that serious games in the health sector

follow Picard’s (2011) basic definition of affective

computing. However, based on the understanding of

player motivation provided by Rigby and Ryan

(2011) and Malone and Lepper (1987), we would

offer the following definition: Serious game design

aims to influence intrinsically motivating factors in

order to deliberately influence emotions.

5 CONCLUSIONS

The key phases of the design and development of SG

are based on a profound analysis and good

understanding of the aim and players of the game

being developed. It is thus important to design

characters and narratives that players can assimilate.

Iterative development and various testing methods

make it possible to check during the development

whether the serious game is working as planned. SG

design takes into account affective computing by

nature: game design deliberately influences emotions

in order to engage players.

As a narrative-intensive visual novel, it was

possible to include in GoML different viewpoints

regarding life management issues. The “role map of a

young person in the process of becoming

independent” provided a sound theoretical

background for the storylines. GoML can be used in

nursing or youth work as a discussion tool to evoke

conversation and thoughts between professionals and

patients, and the game comes with a protocol for its

use.

We are continuing our research on the

development of serious games in the health sector.

The thorough evaluation and validation of GoML

needs to continue further. Identifying the key phases

of designing and developing successful SG continues

with other case studies. We also suggest that future

research into serious games should take into account

new platforms such as virtual reality that will move

affective computing to the next level.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

One of the authors received funding from the Niilo

Helander Foundation in Finland.

REFERENCES

Adams E. (2013). Fundamentals of Game Design (3

rd

edition). Pearson Education, Inc.

Alvarez J. & Rampnoux O. (2007). Serious Game: Just a

Question of Posture? Artificial & Ambient Intelligence,

AISB'07, April, 420–423.

Arnab S., Dunwell I. & Debattista K. (2013). Serious

Games for Healthcare: Applications and Implications.

IGI Global.

Baranowski T., Buday R., Thompson D., Lyons E.J.,

Shirong Lu A. & Baranowski J. (2013). Developing

Games for Health Behavior Change: Getting Started.

Games for Health Journal: Research, Development,

and Clinical Applications, 2(4), 183–190.

Bethke E. (2003). Game Development and Production.

Wordware Publishing, Inc.

Braad E.P., Folkerts J. & Jonker N. (2013). Attributing

Design Decisions in the Evaluation of Game-Based

Health Interventions in Schouten, B., Fedtke, S.,

Bekker, T., Schijven, M., Gekker, A. (Eds.) Games for

Health. Proceedings of the 3rd European Conference

on Gaming and Playful Interaction in Health Care.

Springer Fachmedien, 61-74.

Brox E., Fernandez-Luque L. & Tøllefsen T. (2011).

Healthy Gaming: Video Game Design to Promote

Health. Applied Clinical Information, 2(2), 128–142.

Cavallaro D. (2010). Anime and the Visual Novel:

Narrative Structure, Design and Play at the Crossroads

of Animation and Computer Games. McFarland &

Company Inc.

Deen M., Heynen E.J.E., Schouten B.A.M., van der Helm

P.G.H.P. & Korebrits A.M. (2014). Games 4 Therapy

Project: Let’s Talk! In Schouten, B., Fedtke, S.,

Schijven, M., Vosmeer, M., Gekker, A. (Eds.) Games

for Health 2014. Proceedings of the 4th Conference on

Gaming and Playful Interaction in Healthcare.

Springer Fachmedien.

Desurvire, H., Caplan, M. & Toth, J.A. (2004). Using

Heuristics to Evaluate the Playability of Games.

Extended Abstracts of the 2004 Conference on Human

Factors in Computing Systems. ACM Press. 1509–

1512.

Djaouti D., Alvarez J., Jessel J.-P. & Rampnoux O. (2011).

Origins of Serious Games. Serious Games and

Edutainment Applications. Springer-Verlag London

Limited.

Felicia P. & Egenfeld-Nielsen S. (2011). Game- Based

Learning: A Review of the State of the Art in Egenfeldt-

Nielsen S., Meyer B. & Holm Sorensen B. (Eds.),

Serious Games in Education: A Global Perspective.

Aarhus University Press, 21-46.

Friess R., Kolas N. & Knoch J. (2014). Game Design of a

Health Game for Supporting the Compliance of

Adolescents with Diabetes in Schouten, B., Fedtke, S.,

Schijven, M., Vosmeer, M., Gekker, A. (Eds.) Games

for Health 2014. Proceedings of the 4th Conference on

Gaming and Playful Interaction in Healthcare.

Springer Fachmedien, 37-47.

On the Development of Serious Games in the Health Sector - A Case Study of a Serious Game Tool to Improve Life Management Skills in

the Young

141

Fullerton T. (2014). Game Design Workshop: A Playcentric

Approach to Creating Innovative Games. Taylor &

Francis Group, LLC.

Gabriel S. & Young A.F. (2011). Becoming a Vampire

Without Being Bitten: The Narrative Collective-

Assimilation Hypothesis. Psychological Science, 22(8),

990–994.

Graafland M., Dankbaar M., Mert A., Lagro J., De Wit-

Zuurendonk L., Schuit S., Schaafstal A. & Schijven M.

(2014). Viewpoint How to Systematically Assess

Serious Games Applied to HealthCare. JMIR Serious

Games, 2(11), 1–8.

Iovane G., Salerno S., Giordano P., Ingenito G. and

Mangione G.R. (2012). A Computational Model for

Managing Emotions and Affections in Emotional

Learning Platforms and Learning Experience in

Emotional Computing Context in Barolli L., Xhafa F.,

Vitabile S., and Uehara M. (Eds.) Complex, Intelligent

and Software Intensive Systems (CISIS). Sixth

International Conference, 873-880.

Jessen C. (2011). Learning Games and the Disruptive

Effects of Play in Egenfeldt-Nielsen S., Meyer B. &

Holm Sorensen B. (Eds.), Serious Games in Education:

A Global Perspective. Aarhus University Press, 153-

169.

Kaleva J., Hiltunen K. & Latva S. (2013). Mapping the Full

Potential of the Emerging Health Game Markets. Sitra

Studies, 72. Retrieved 5 February, 2017, from

http://www.sitra.fi/julkaisut/Selvityksiä-

sarja/Selvityksia72.pdf

Kemppainen, J., Korhonen, T. & Ravelin, T. (2014).

Developing Health Games Requires Multidisciplinary

Expertise. Finnish Journal of eHealth and eWelfare,

6(4), 200–205.

Lu A.S., Baranowski T., Thompson D. & Buday R. (2012).

Story Immersion of Videogames for Youth Health

Promotion: A Review of Literature. Games Health

Journal, 1(3), 199–204.

Lu B. (2014). Hikikomori: The Need to Belong and the

Activation of Narrative Collective-Assimilation

through Visual Novels. Journal of Interpersonal

Relations, Intergroup Relations and Identity, 7, 50–61.

Malone, T. & Lepper M. (1987). Making Learning Fun: A

Taxonomy of Intrinsic Motivations for Learning. In

Snow, R. & Farr, M.J. (Eds.), Aptitude, Learning, and

Instruction. Volume 3: Conative and Affective Process

Analyses. Hillsdale, NJ, 223–253.

Marczewski, A. Gamified UK. Game Thinking. Retrieved

4 March, 2015 from http://www.gamified.uk/

gamification-framework/differences-between-

gamification-and-games/

Merry S., Stasiak K, Shepherd M., Frampton C., Fleming

T. & Lucassen M. (2012). The effectiveness of SPARX,

a Computerised Self-Help Intervention for Adolescents

Seeking Help for Depression: Randomised Controlled

Non-Inferiority Trial. BMJ, 344(2598), 1–16.

Moore M. (2011). Basics of Game Design. Taylor and

Francis Group, LLC.

Picard R.W. (2010). Affective Computing: From Laughter

to IEEE in Gratch J. (Ed.) IEEE Transactions on

Affective Computing, 1(1). IEEE, 11-17.

Rigby, S. & Ryan, R.M. (2011). Glued to Games. How

Video Games Draw Us In and Hold Us Spellbound.

ABC-Clio, LLC.

Rollings A. & Adams E. (2003). On Game Design. New

Riders Publishing.

Ryan R.M., ·Rigby S. & Przybylski A. The Motivational

Pull of Video Games: A Self-Determination Theory

Approach. Motivation and Emotion 30(4), 344–360.

Salen K. & Zimmerman E. (2004). Rules of Play: Game

Design Fundamentals. Massachusetts Institute of

Technology.

SPARX Fact Sheet. Retrieved 3 March, 2015,

fromhttps://www.fmhs.auckland.ac.nz/assets/fmhs/fac

ulty/ABOUT/newsandevents/docs/SPARX%20Fact%

20sheet.pdf

Susi T., Johannesson M. & Backlund, P. Serious Games:

An Overview. Technical Report HS-IKI-TR-07-001.

Retrieved 11 March, 2015, from

http://www.scangames.eu/downloads/HS-IKI-TR-07-

001_PER.pdf

Yannakakis G.N. & Togelius J. (2011). Experience-Driven

Procedural Content Generation. IEEE Transactions on

Affective Computing, 2(3). IEEE, 147-161.

Yannakakis G.N., Isbister K., Paiva A. & Karpouzis K.

(2014). Guest Editorial: Emotion in Games. IEEE

Transactions on Affective Computing, 1(5). IEEE, 1-2.

Ylitalo, P. (2011). Role Map of a Young Person in the

Process of Becoming Independent. Roolikartta

vanhemmuuden, parisuhteen ja itsenistymisen tueksi.

Suomen kuntaliitto, 33−81.

ICEIS 2017 - 19th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

142