Improving Communication in Online Learning Systems

Godfrey Mayende

1,2

, Andreas Prinz

1

and Ghislain Maurice N. Isabwe

1

1

Department of Information and Communication Technology, University of Agder, Grimstad, Norway

2

Institute of Open, Distance and eLearning, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda

Keywords: Online Learning, Communication, Collaborative Learning, Online Learning Systems.

Abstract: In this paper, we study communication in online learning systems using both quantitative and qualitative

research methods. Quantitative methods provide the interaction statistics, while qualitative content analysis

was used for categorisation of the messages. It turns out that 20% of the active participants dominate the

online learning interactions, and more than 80% are passive consumers. From the categorization, we learned

that most of the communication is not related to learning, but to technical problems (26%), small talk

(29%), sharing experience (16%), and encouragement (11%). Only 10% are related to the content. For

improved communication, it is therefore important to use the right communication tools in the online

learning systems. Especially, learning by content creation should be provided.

1 INTRODUCTION

Distance learning is a mode of study where students

have minimal face-to-face contact with their

facilitators; the learners learn on their own, away

from the institutions, most of the time (Aguti and

Fraser, 2006). Nevertheless, (Vygotsky, 1978)

argues that a person’s learning may be enhanced

through engagement with others. Use of computer

supported collaborative learning can offer

possibilities of students’ interactions (Muyinda et

al., 2015). In particular, technology can help

virtually form learning such that learners can learn

collaboratively (Mayende et al., 2015a). However,

motivating and sustaining effective student

interactions requires planning, coordination and

implementation of curriculum, pedagogy and

technology (Stahl et al., 2006).

Online learning systems often include a way to

support learner interaction, either by integrating with

Facebook or using an own system for that purpose.

We look into three large online courses with

communication support, namely Uncompromised

Life, Soulvana and Duality. All of them are paid

courses in the area of personal development, such

that we can assume high dedication from the side of

the learners. The communication possibilities in all

three courses were similar, even though one of the

courses uses Facebook, while the other two use a

separate platform.

Engagement in online learning systems is

achieved through active participation on these

communication platforms. It is our intention to find

out how to make learners more engaged in online

courses. We hope this will in turn bring about

meaningful learning. This is based on the view that

active participation in a course by communicating is

associated with better learning output.

The paper continues in section 2 with reviewing

the collaborative learning. Section 3 describes the

courses we have studied, while section 4 presents the

approaches and research methods. The finding are

presented in section 5 and good practice for online

course design in section 6. Finally, the paper is

concluded in section 7.

2 COLLABORATIVE LEARNING

Collaborative learning refers to instructional

methods that encourage students to work together to

find a common solution (Ayala and Castillo, 2008).

collaborative learning involves joint intellectual

effort by groups of students who are mutually

searching for meanings, understanding or solutions

through negotiation (Ashley, 2009; Stahl et al.,

2006). This approach is learner-centred rather than

teacher-centred; views knowledge as a social

construct, facilitated by peer interaction, evaluation

and cooperation; and learning as not only active but

300

Mayende, G., Prinz, A. and Isabwe, G.

Improving Communication in Online Learning Systems.

DOI: 10.5220/0006311103000307

In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2017) - Volume 1, pages 300-307

ISBN: 978-989-758-239-4

Copyright © 2017 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

interactive (Vygotsky, 1978). This interaction is in

line with Anderson’s online learning framework

which argues that learning can be achieved through

student-teacher, student-student, and student-content

interactions (Anderson, 2003). This is also apt with

(Stahl et al., 2006) who asserts that learning takes

place through student-student interactions. Students

effectively develop deep learning when using

computer supported collaborative learning

(Ludvigsen and Mørch, 2009). Therefore, careful

integration of computer supported interaction can

heavily increase learning in online learning systems.

Collaborative learning is based on consensus

building through interaction by group members, in

contrast to competition. This can be very helpful for

distance learners, who are typically adults.

Collaborative activities are essential to encourage

information sharing, knowledge acquisition, and

skill development (Collison et al., 2000). Different

technology tools have been adopted for

collaboration in distance learning.

Collaborative learning hinges on the belief that

knowledge is socially constructed although each

learner has control over his/her own learning. Online

learning systems offer possibility for these

collaborations to be achieved through

communication among learners. Collaborative

learning is underpinned by the social constructivist

learning theory (Vygotsky, 1978). This is used in the

online courses studied and described in the section

below.

3 THREE ONLINE COURSES

We study three online courses, which are offered by

Mindvalley in the personal development area. They

are paid and use the Mindvalley platform for the

course material. For one course, the discussion is run

in a closed Facebook group, while for the other two

the Mindvalley discussion platform is used. For the

sake of this article, the discussion functionality in

Mindvalley is designed like Facebook.

Mindvalley is an online teaching company in the

personal development area. It focuses on life skills

that regular schooling does not cover, based on the

world's top personal growth authors and brands. The

Mindvalley teaching platform features a discussion

area structured like Facebook.

Facebook is a social media online platform built

with no perceived affordance for teaching and

learning. Nevertheless, many studies have used it for

teaching and learning and it is promising for

increasing interaction in groups (Li et al., 2016;

Mayende et al., 2014; Munguatosha et al., 2011).

3.1 Uncompromised Life

This course teaches everyday psychology to sort out

the day and night things that matter in life. The

course runs for eight weeks and learners are taught

eight transformations. The following elements are

discussed: focus and clarity of mind, mental models,

law of attraction, handling change, productivity,

daily habits, self-love, and self-confidence. This

course is purely run online using the Mindvalley

online learning system and the Mindvalley

discussion platform.

3.2 Duality

This Mindvalley course is related to the duality

between energy and reality. It runs for eight weeks

and teaches the following seven improvements:

getting fast answers, manifesting the life you want,

feeling happy now, stopping the fight against

yourself, accelerated healing, perfect relationships,

and living your ultimate life. This course is purely

run online using the Mindvalley online learning

system with discussions in a closed Facebook group.

3.3 Soulvana

Soulvana is not a course, but a subscription. It does

not have duration, but presents a new teaching every

week. Often, the teaching is related to other courses

in Mindvalley, or given by authors that are

connected to Mindvalley. Due to the format, the area

is broader than the other two courses. The

connection between the topics in Soulvana is the

focus on spirituality and its use to improve everyday

life. Just like the other two this course is run on the

Mindvalley platform including discussions.

4 APPROACHES AND METHODS

4.1 Communication in a Course

This paper uses three categories of course

communication: discussion, message and creation.

Discussion is a transient exchange of

information. The Cambridge dictionary defines

discussion as the activity in which people talk about

something and tell each other their ideas or opinions

(Dictionary, 2008). This communication can be both

verbal or non-verbal, sychronous or asychronous.

Improving Communication in Online Learning Systems

301

Discussions are often supported within online

learning systems using text based asychronous

discussion threads.

Message is a one-way information exchange.

The Cambridge dictionary defines a message as a

short piece of information that you give to a person

when you cannot speak to them directly (Dictionary,

2008). This communication can be both verbal or

non-verbal. Messages are important when

communicating to the students about something in

the online learning systems. A typical way to send

messages is email communication, or course

messages.

Creation is communication with the purpose of

creating something. An example is the creation of a

poem by a group of students. Here, the

communication does not directly lead to the end

results, but rather supports it. This part can be

available in online learning systems as co-creation of

artifacts, group projects, pair programming, debate

and wiki. In our three selected courses, creation was

not available.

4.2 Methods

The communications in the three online courses

were analysed from the autumn 2015 until January

2016. Uncompromised Life and Soulvana messages

were extracted from the Mindvalley platform, while

Duality course messages were extracted from

Facebook. Quantitative methods were used on the

three data sets to get the general statistics related to

communication and participation within these three

courses.

For a deeper understanding, content analysis was

done by manually categorizing the type of messages

being communicated. Then the different categories

were analysed statistically to understand what was

happening in the online interactions. The chosen

categories are based on an a-priori opinion of the

kind of messages in the set. This way, some

messages could fit more than one category. In these

cases, the best fit was chosen.

5 FINDINGS

This section describes the findings of the study. It is

divided into three parts; the general participation of

the online courses, interaction in the online courses

and communication needs for online learning

systems.

5.1 General Participation

This part describes the general statistics of the

findings from the three online courses, divided into

enrolments in the online courses, participation in the

discussions and discussion threads in the online

courses.

5.1.1 Enrolment in the Online Courses

The three online courses had large class sizes. Each

of the courses had at least 3,000 partcipants enrolled,

with Uncompromised Life, Soulvana and Duality

having 3,385, 3,464 and 3,000 participants,

respectively. The number for Duality is an educated

guess, as there was no accurate number of

participants in Duality available. These numbers are

comparable to enrolment of MOOCs (Meinel et al.,

2014; Salmon et al., 2015; Salmon et al., 2016). Far

less participated with sending at least one message

on the platforms, namely 625 (18%) for

Uncompromised Life, 638 (18%) for Soulvana and

350 (12%) for Duality. We see that most of the

participants were passive consumers of content. The

lower participation for Duality is probably due to the

manual enrolment into the Facebook group, while

the other two courses had automatic enrolment into

the Mindvalley discussion platform.

5.1.2 Participation in the Discussions

This shows the active participation on online course.

In this study active participation is communicating

by sending atleast one message. The percentage of

active participation in the courses were 18%, 18%

and 12% for Uncompromised life, Soulvana and

Duality respectively. The active participants were

also active in starting own discussion threads, and

not only answering to the existing threads. Own

discussion threads were started by 57%, 43% and

65% of the active participants in Uncompromised

Life, Soulvana and Duality, respectively.

The Pareto principle which maintains that 80%

of output from a given situation or system is

determined by 20% of input, applies for the

messages. This is so because twenty percent (20%)

of the active participants contributed almost 80% of

the total messages. Another interesting statistics is

the ratio of messages by the teaching team. On the

Mindvalley platform, the teachers contributed 18%

of the messages, in contrast to only 3% in the

Facebook group. Finally, there was always one very

active person, contributing around 10% of all the

messages alone.

CSEDU 2017 - 9th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

302

5.1.3 Analysis of Discussion Threads

Figure 1 shows the analysis of discussion threads.

We remember that threads were started by around

50% of the active participants. We found that the

threads are mostly discussions. They have on

average a relatively small number of messages in

them (5, 4, and 8), and their life span is short (2.5,

1.2, and 1.3 days).

Figure 1: Thread patterns in Online Courses.

This indicates that the platforms are not suited

for long-time interactions. In both platforms, threads

pop up higher in the ranking when they are active.

This way it is possible that few threads have a long

life (maximum 130 days with 195 messages in

Soulvana). For comparison, Uncompromised Life

has maximum 49 days with 83 messages, while

Duality has maximum 62 days with 26 messages.

That analysis indicates that there was minimal

learning taking place in the discussions, which is

examined more closely in the next part.

5.2 Interactions in the Online Courses

Interaction is very important in online learning

systems. Therefore, we want to understand the kind

of interactions going on in the online learning

systems. As explained in Section 4.2, we analysed

the content of the messages. Categories were defined

a priori and the messages were sorted into the

categories. Table 1 shows the result of the sorting.

A major part of the communication is geared around

technical problems (26%). These were questions

aimed at asking for help on how to use the online

learning system. It turned out that the discussion

Table 1: Interaction messages being communicated.

Major Category Sub category % %

Technical

problems

Technical questions 14%

26%

Answers to technical

questions 12%

Smalltalk

Introduction of

people 4%

29%

Welcomes 5%

Thanks 18%

General Smalltalk 2%

Content

Content questions 4%

10%

Answers to content

questions 6%

Sharing

experience

Sharing experience 11%

16%

Agreement with

experiences 5%

Encouragement

Encouragement 11%

11%

Others

Connection between

people 2%

8%

Create something

jointly 0%

Empty & unrelated 6%

platform was not a good place to handle such

problems, as the same questions and answers used to

turn up in regular intervals. It was impossible to find

out if the same question was asked before and it was

even difficult to find the correct answer if it was in

the same thread. Most of these interactions were

more of a message kind, and a discussion kind.

The second major category was smalltalk

messages contributing with 29%. Smalltalk is very

important in group dynamics since groups of these

students have to go through the different phases of

the group for it to be effective, from Tuckman five

stage model (Tuckman and Jensen, 1977).

Ten percent (10%) of the messages were related

to content: asking questions and getting responses to

the questions. The content interactions are closest to

the idea of learning by communication, as they

directly involve the material taught.

The second major learning related interaction is

the sharing experiences with 16% of the messages.

Sharing is important in personal growth courses, as

learning is exactly about own experiences. Still,

learning in this case happens outside the system, and

only the result are reflected in the platform.

In a similar way, encouragement helps with

motivation for the learning, but is not related to the

learning itself. Encouragement contributed 11% of

the messages.

Improving Communication in Online Learning Systems

303

The remaining messages are largely not

categorized, including empty and unrelated posts.

However, there are two categories that deserve

mention: there are 2% of messages related to

connection between people, mostly based on same

language and/or same location. This indicates that

people are interested in communication in their own

language and face to face. Finally, there are 13

messages where some participants attempted to

create something jointly, which is marginally related

to the total number of messages.

Considering only the teachers, the situation is as

follows: 15% content answers, 35% technical

answers, 16% encouragement, 10% thanks, and 16%

welcome plus few uncategorized posts.

The kind of interactions changed over time, this

is shown in the differences in focus from December

to January.

• technical questions 31% -> 22%

• smalltalk 21% -> 3%

• thanks 15% -> 21%

• content 5% -> 14%

• sharing 22% -> 31%

• rest 6% -> 9%

This indicates that the participants get more

focused and experienced with the platform which

brings a shift from smalltalk and technical questions

to content and sharing experience.

A general observation is that the interactions are

full of recurring questions, both related to content

and technical questions, sometimes even in the same

thread. This indicates that the systems are designed

for discussions, where it is not planned to go back to

previous arguments. In a discussion, the interactions

are only the background, and they do not have a life

on their own. This is in contrast to messages, which

are important on their own and need to be searchable

and easily accessible. This is even more important

with large numbers of participants.

5.3 Communication Needs

Based on the findings in the previous section and

knowing that engagement can be achieved through

communication, the following communication needs

are derived from the analysis. The three different

forms of communication (discussion, message and

creating) are used as a basis for the needs.

Announcements communicate course status and

progress. They can trigger learner engagement and

improve the feeling of teacher presence within the

online learning systems. This is basically a message

communication. The best way to implement

announcements is by using a message board, which

can be embedded in the users home page. The

systems analyzed in this paper do not properly

support this component, and use discussions instead.

Course administration information is related to

the course structure and in this way an equally vital

one-way communication message. The best way of

implementing them starts already outside the online

system with a clear structure and description of the

course. Then it can be shown with clean pages

followed by good help pages. The systems analyzed

here again used discussions for this component,

which is not appropriate.

Course material refers to the content of the

course, including text, videos, and audios. This is

message communication, and as the course

administration information, a clear structure that is

visible in the course is the best way to implement it.

This component is very important because it feeds

into other communication types of discussion and

creation. The main point here is to have a good

description of the activities that connects well to the

course materials, which can motivate learners to

engage with course materials. This is further

discussed in the next section.

Sharing, support, and encouragement can be

done in both small and big groups because they help

in motivating learners in the online learning systems.

This is a discussion, where the result is created

during the interaction, and the thread itself is

auxiliary. It is important to establish a code of

conduct for the discussion groups, including privacy

(non-disclosure). Dunbar's number suggests that 150

is the cognitive limit to the number of people with

whom one can maintain stable social relationships

(Dunbar, 2010). These are relationships in which an

individual knows who each person is and how each

person relates to every other person. Above that

number, groups will give a feeling of anonymity,

which could help to share some more embarrassing

information (Gonçalves et al., 2011). For group

discussions in your course, a group size of five

would be more effective (Mayende et al., 2015a).

Discussion and clarification are used when

dealing with course content. These are discussion

interactions and they do not produce results, but are

just auxiliary. If well planned and organised they

lead to changes in the content and learning. Usually,

if they are triggered by activities around the content

they can enhance engagement and learning.

CSEDU 2017 - 9th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

304

6 GOOD PRACTICES FOR

ONLINE COURSE DESIGN

6.1 Communication in Online Learning

Systems

Based on the findings we suggest ways to improve

communication in online learning systems. There are

several areas where learning happens in online or

traditional settings, which are not currently used in

the studied courses. These kinds of communication

are related to more active modes of learning, like

discussion groups, practice by doing and teaching

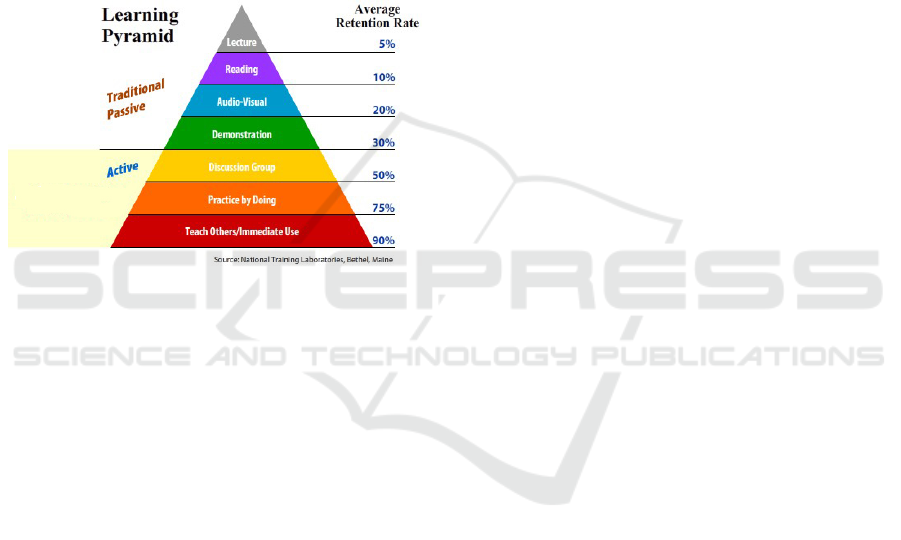

others/immediate use as shown in the figure 2.

Figure 2: Learning Pyramid.

It is important to be clear that the modes of

communication used here are most often not

discussions. We collect the recommendations below:

Individual content allows users to store content

related to their learning, probably somewhere in the

user area related to the course. It is not limited to

individually complete questionnaires, quizzes, and

reflections. These are in the category of (one-way)

message, but here they belong to the user.

Joint content is content that is created by groups

of learners, maybe all learners in a course. It helps to

create content jointly; good examples are wiki pages

and google docs. These fall into the category of

creation, and do not exist in the studied online

learning systems. A discussion might be associated

to the joint content.

Learning groups are important for dedicated and

meaningful learning. These groups are connected to

a joint task, for example discussing a statement or

creating something. In terms of communication, this

is a combination of discussion and joint or

individual content. The discussion is used in order to

create, but disappears later. It is also possible that

nothing is created apart from learning.

Mentoring (coaching) for groups provides input

to the individual or the group process. This is very

important for learning groups as the groups tend to

get stuck once in a while. By mediating learning, the

mentors can provoke learners to discuss issues that

they would not have discussed otherwise. The

mentoring often does not result in an artifact, but it

may contribute to an improved artifact.

Peer-to-peer evaluation and assessment. In a

learning setting, peer-to-peer evaluation is a

feedback message mechanism supporting learning. It

can be embedded into the learning process at several

places, not only at the end. Peer assessment can be

based on groups or on individuals. When well

embeded within the course structure improved

learning can be achieved (Mayende et al., 2015b;

Mayende et al., 2017).

6.2 Synchronous Communication and

Physical Contact

Communication in online learning often lends itself

to an asynchronous mode, because learners may

have different time zones and different times to

access the learning environment. There is a general

trend to rely more on virtual connection than

physical ones (Turkle, 2012). However, from a

learning perspective, this is not the best option. For

improved learning, also synchronous communication

should be considered.

Mehrabian found that 7% of any message is

conveyed through words, 38% through certain vocal

elements, and 55% through nonverbal elements

(facial expressions, gestures, posture, etc)

(Mehrabian, 1971). Typical discussion forums like

in Mindvalley and Facebook use only the 7% part,

and therefore miss out much on the other

components.

At the University of Agder online courses, we

arrange a physical meeting with the course

participants which is then used as a basis for the

asynchronous and online communication. This

improves engagement a lot. Equally at Makerere

University we arrange physical meetings of two

weeks twice a semester which improves engagement

when studying the courses.

Experiences with lecture streaming and capture

at University of Agder indicate that the (perceived)

live event of a lecture is much more valuable than

the playback. In particular, this leads to the fact that

students follow what is said more closely. It seems

that the important aspect is the synchronous

communication, and in particular the life presence of

the students (not necessarily the teacher). Based on

Improving Communication in Online Learning Systems

305

this experience, it is not a good idea to run video

lectures as non-timed playback, but rather organize

several time slots where the students meet at the

same time.

Life communication in a large group of

participants (more than 10) will typically be

restricted to statistical interaction (raise your hands)

and can be implemented using Kahoot

(https://getkahoot.com/). However, group processes

in learning (learning by discussing) are typically

connected to synchronous meetings. These have to

be in smaller groups (around 5).

Of course, after knowing that synchronous

communication is good, and physical meetings are

even better for learning, the question is how to

facilitate that for an online learning system. Here are

some suggestions.

Synchronous communication can be planned into

a course by setting time slots for some of the video

lectures. Typically, two time slots per day are

enough to cater for all time zones. It is essential in

this case to embed also synchronous communication

into the video itself, in particular activities for the

students, like polls. Moreover, in many cases online

courses have a geographical clustering of the

participants, such that occasional face to face

meetings are possible. A clever move in this context

is to motivate the students to invite their friends and

family into the course such that physical meetings

can work out more easily.

Of course, synchronous communication has to be

planned for in the course design, such that as a result

the retention rate for the learning really is improved

above the one-way messages.

Finally, introducing synchronous communication

would also introduce a need to teach about how to

handle such discussions in a learning context.

Effective work in groups needs special processes to

check into the group (presenting your personal

status), both in a face-to-face and in an online

synchronous setting.

7 CONCLUSION

From the online communication patterns identified

from the online learning courses studied in this

paper, the following conclusions have been arrived

at. First, in online learning systems, the first message

to be sent is the most difficult one. So it might be a

good idea to focus on the first message specifically.

Second, 20% of the participants contribute about

80% to the message traffic. This means there has to

be enough traffic in total to allow students to be

active even if they are not among the most active

20%. Third, Facebook and similar systems are

optimized towards discussions with short time

horizon and small number of exchanged messages.

They are not equally good at other forms of

communication like one-way communication or co-

creation. Fourth, a good communication for learning

needs both a joint discussion area for all learners,

and a learning group communication area for smaller

learning groups. Fifth, synchronous communication

should also be emphasized in the platforms and

more importantly in the course design.

Creation can lead to meaningful learning within

learning groups. Many online learning discussion

platforms are built in a Facebook like setup, which

makes it difficult for learners to create knoweldge. A

proper way to support co-creation of artifacts and of

knowledge will advance online learning systems a

lot.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The work reported in this paper was supported by

the DELP project (funded by NORAD) and the

ADILA Project (funded by UiA).

REFERENCES

Aguti, J. N., & Fraser, W. J. (2006). Integration of

Information Communication Technologies (ICTs) in

the Distance Education Bachelor of Education

Programme, Makerere University, Uganda. Online

Submission.

Anderson, T. (2003). Modes of Interaction in Distance

Education: Recent Developments and Research

Questions. In M. Moore & G. Anderson (Eds.),

Handbook of Distance Education. (pp. 129-144). NJ:

Erlbaum.

Ashley, D. (2009). A Teaching with Technology White

paper. Collaborative Tools. Retrieved on November 1,

2014 from

http://www.cmu.edu/teaching/technology/whitepapers/

CollaborationTools_Jan09.pdf.

Ayala, G., & Castillo, S. (2008). Towards computational

models for mobile learning objects. Paper presented at

the Wireless, Mobile, and Ubiquitous Technology in

Education, 2008. WMUTE 2008. Fifth IEEE

International Conference on.

Collison, G., Elbaum, B., Haavind, S., & Tinker, R.

(2000). Facilitating online learning: Effective

strategies for moderators: ERIC.

Dictionary, C. (2008). Cambridge Advanced Learner’s

Dictionary: PONS-Worterbucher, Klett Ernst Verlag

GmbH.

CSEDU 2017 - 9th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

306

Dunbar, R. (2010). How many friends does one person

need?: Dunbar's number and other evolutionary

quirks: Faber & Faber.

Gonçalves, B., Perra, N., & Vespignani, A. (2011).

Modeling users' activity on twitter networks:

Validation of dunbar's number. PloS one, 6(8),

e22656.

Li, Q., Lau, R. W., Popescu, E., Rao, Y., Leung, H., &

Zhu, X. (2016). Social Media for Ubiquitous Learning

and Adaptive Tutoring [Guest editors' introduction].

IEEE MultiMedia, 23(1), 18-24.

Ludvigsen, S., & Mørch, A. (2009). Computer-supported

collaborative learning: Basic concepts, multiple

perspectives, and emerging trends, in The International

Encyclopedia of Education, 3rd Edition, edited by B.

McGaw, P. Peterson and E. Baker, Elsevier (in press).

Mayende, G., Isabwe, G. M. N., Muyinda, P. B., & Prinz,

A. (2015b). Peer Assessment Based Assignment to

Enhance Interactions in Online Learning Groups.

Paper presented at the International Conference on

Interactive Collaborative Learning (ICL), 20-24

September 2015, Florence, Italy.

Mayende, G., Muyinda, P. B., Isabwe, G. M. N.,

Walimbwa, M., & Siminyu, S. N. (2014). Facebook

Mediated Interaction And Learning In Distance

Learning At Makerere University Paper presented at

the 8th International Conference on e-Learning, 15 –

18 July, Lisbon, Portugal.

Mayende, G., Prinz, A., Isabwe, G. M. N., & Muyinda, P.

B. (2015a). Supporting Learning Groups in Online

Learning Environment. Paper presented at the CSEDU

2015 - 7th International Conference on Computer

Supported Education, Lisbon, Portugal.

Mayende, G., Prinz, A., Isabwe, G. M. N., & Muyinda, P.

B. (2017). Learning Groups for MOOCs Lessons for

Online Learning in Higher Education. In M. E. Auer,

D. Guralnick, & J. Uhomoibhi (Eds.), Interactive

Collaborative Learning: Proceedings of the 19th ICL

Conference - Volume 1 (pp. 185-198). Cham: Springer

International Publishing.

Mehrabian, A. (1971). Silent messages (Vol. 8):

Wadsworth Belmont, CA.

Meinel, C., Willems, C., Renz, J., & Staubitz, T. (2014).

Reflections on enrollment numbers and success rates

at the openhpi mooc platform. Proceedings of the

European MOOC Stakeholder Summit, 101-106.

Munguatosha, G. M., Muyinda, P. B., & Lubega, J. T.

(2011). A social networked learning adoption model

for higher education institutions in developing

countries. On the Horizon, 19(4), 307-320.

Muyinda, P., Mayende, G., & Kizito, J. (2015).

Requirements for a Seamless Collaborative and

Cooperative MLearning System. In L.-H. Wong, M.

Milrad, & M. Specht (Eds.), Seamless Learning in the

Age of Mobile Connectivity (pp. 201-222): Springer

Singapore.

Salmon, G., Gregory, J., Lokuge Dona, K., & Ross, B.

(2015). Experiential online development for educators:

The example of the Carpe Diem MOOC. British

Journal of Educational Technology, 46(3), 542-556.

Salmon, G., Pechenkina, E., Chase, A. M., & Ross, B.

(2016). Designing Massive Open Online Courses to

take account of participant motivations and

expectations. British Journal of Educational

Technology.

Stahl, G., Koschmann, T., & Suthers, D. (2006).

Computer-supported collaborative learning: An

historical perspective. Cambridge handbook of the

learning sciences, 2006.

Tuckman, B. W., & Jensen, M. A. C. (1977). Stages of

small-group development revisited. Group &

Organization Studies, 2(4), 419-427.

Turkle, S. (2012). Alone together: Why we expect more

from technology and less from each other: Basic

books.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: the development

of higher psychological processes. Cambridge::

Harvard University Press.

Improving Communication in Online Learning Systems

307