ReMindMe: Agent-based Support for Self-disclosure of Personal

Memories in People with Alzheimer’s Disease

Marieke M. M. Peeters

Delft University of Technology, Interactive Intelligence Group, Delft, The Netherlands

Keywords:

Human-agent Relationships, Conversational Agent, Ontology, Self-disclosure, Dementia.

Abstract:

This paper presents work on the design rationale and architecture of ReMindMe. ReMindMe aims to pro-

vide agent-based support for people with Alzheimer’s disease and their social environment by playing music

with a strong personal meaning to the patient so as to activate personal memory recall. ReMindMe stimulates

reminiscence and self-disclosure of personal memories. Through long-term interaction with the patient, the

ReMindMe agent gradually constructs a knowledge base containing information about the patient’s life sto-

ries. The agent uses this knowledge base to engage in mutual conversational self-disclosure about personal

memories so as to stimulate reminiscence. Future research aims to develop and refine ReMindMe through

coactive design and testing ‘in the wild’, i.e. at dementia care facilities. The envisioned outcome of the project

is a usable and effective proof-of-concept of a conversational agent for the dementia care practice.

ENVISIONED SCENARIO

Over the past two years, Mrs. de Vries’s dementia

progressively worsened. It became difficult for her to

keep a conversation or play a game. Her granddaugh-

ter, Susan, no longer knew how to connect with her

grandmother and visited less and less frequent. As of

late, however, Susan has found a new way to interact

with her grandmother: through ReMindMe.

Susan enters her grandmother’s room in the nurs-

ing home and sits down next to her grandmother. She

asks if Mrs. de Vries would like to listen to music

together. When Mrs. de Vries nods, Susan asks Re-

MindMe to play music from the playlist “Adolescence

(1940–1945)”. The song “Lili Marleen” by Marlene

Dietrich starts playing.

ReMindMe knows about facts and anecdotes from

Mrs. de Vries’s life between 1940 and 1945. It uses

this knowledge to engage in conversation with Susan

and Mrs. de Vries: “It was 1945. You were staying at

your aunt’s house, when the allied forces arrived. The

tanks drove down the streets, and American soldiers

were handing out chocolate and cigarettes.” Mrs. de

Vries hums to the tune of the song and mumbles: “Yes,

the tanks, the parade, and the flags.” Mrs. de Vries

looks up at Susan. They smile at each other, while

softly singing along with Marlene.

1 PROBLEM STATEMENT

The populations of modern societies are aging, caus-

ing the number of people with Alzheimer’s disease

to rise each year (World Health Organization, 2015).

Alzheimer’s disease has deteriorating effects on pa-

tients’ emotional, cognitive, behavioural, and social

functioning (van Gennip et al., 2014; Verhey, 2015).

Patients’ memories are affected, causing them to for-

get where they put their keys, where they are, or

where they live; they may no longer recognize the im-

portant people in their life, know how to cook a meal,

or how to follow a recipe. Such experiences can lead

to feelings of lowered self-esteem, loss of autonomy,

confusion, depression, and anxiety (Alzheimer’s As-

sociation, 2015).

As of yet, there exists no treatment to cure

Alzheimer’s disease (World Health Organization,

2015). Medicinal treatments of Alzheimer’s dis-

ease primarily aim to reduce the syndrome’s nega-

tive effects, yet the benefits of available medicinal

treatments often do not outweigh their negative side-

effects (Banerjee et al., 2009; Koopmans et al., 2015).

An alternative to medicinal treatments, is the use

of psychosocial interventions: non-medicinal treat-

ments that aim to support and improve the quality of

life for people with Alzheimer’s disease, while mod-

erating the negative implications caused by the syn-

drome (Dro

¨

es et al., 2006; Lawrence et al., 2012;

Peeters, M.

ReMindMe: Agent-based Support for Self-disclosure of Personal Memories in People with Alzheimer’s Disease.

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health (ICT4AWE 2016), pages 61-66

ISBN: 978-989-758-180-9

Copyright

c

2016 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

61

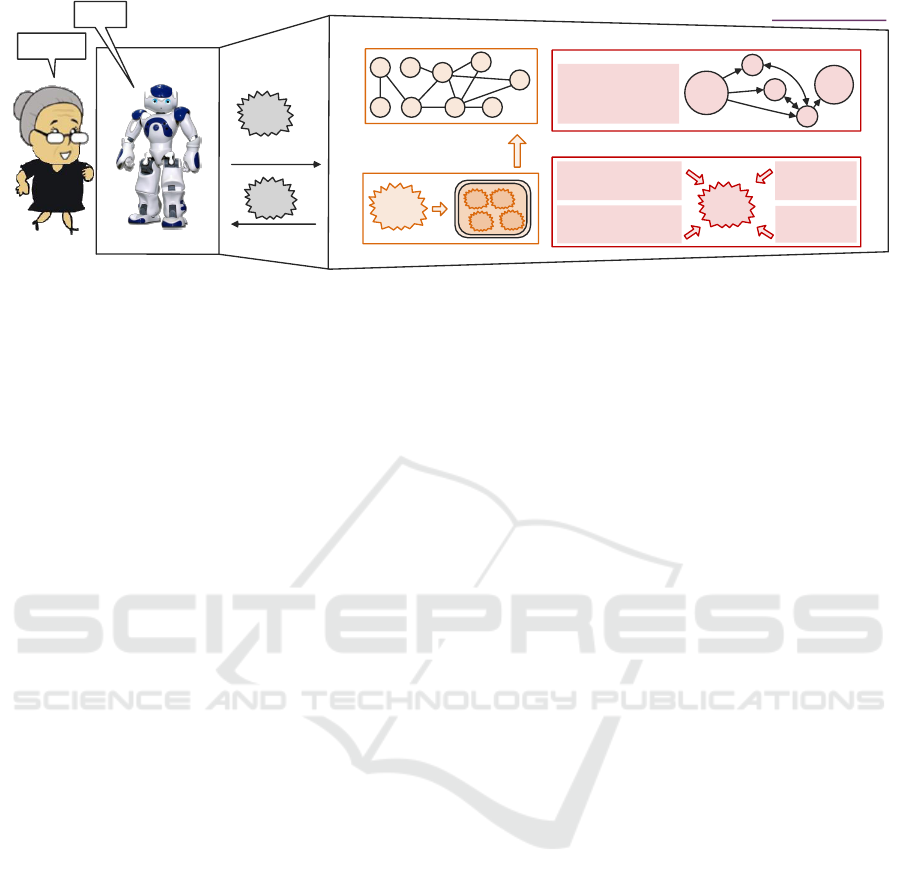

Favourite

music

activates

personal

memories.

ReMindMe

supports

self-disclosure

of the

patient’s

personal

memories.

The patient’s caregivers add her

favourite music to ReMindMe.

Figure 1: ReMindMe: agent-based support for the dementia care practice.

Riley et al., 2009). Patients greatly benefit from

a supportive social environment that regards them

as complete individuals rather than as people with

Alzheimer’s disease (van Gennip et al., 2014). And

so, psychosocial interventions also take patients’ so-

cial environment into account, e.g. family, friends,

and caregivers (Dro

¨

es et al., 2006; Lawrence et al.,

2012; van Gennip et al., 2014; Wallace et al., 2012).

This holistic view on dementia care is particularly im-

portant as the disabilities caused by Alzheimer’s dis-

ease often force patients to increasingly rely on their

social environment, causing a major physical, emo-

tional, and economic impact on the lives of their fam-

ily and friends (Alzheimer’s Association, 2015; van

Gennip et al., 2014; Verhey, 2015).

2 DESIGN RATIONALE

This paper introduces preliminary work on the de-

sign and architecture of a system called ReMindMe:

an agent-based support system for people with

Alzheimer’s disease and their social environment

(also see Figure 1). It also describes a research pro-

posal for the further development and evaluation of

this system.

ReMindMe helps patients and their caregivers in

two ways. First of all, it aids patients in recalling

personal memories, thereby reinforcing their sense of

identity, security, safety, and self-esteem (Dro

¨

es et al.,

2006; Lawrence et al., 2012; van Gennip et al., 2014;

Wallace et al., 2012). Second, ReMindMe stimu-

lates self-disclosure, i.e. the mutual sharing of per-

sonal memories with kindred parties (Derlega et al.,

2008; Dindia et al., 2002; Greene et al., 2006). Self-

disclosure is important for the development and main-

tenance of high-quality interpersonal relationships.

Such relationships are characterised by a mutual lik-

ing, familiarity, and security (Chan and Cheng, 2004;

Collins and Miller, 1994; Greene et al., 2006; Pe-

cune et al., 2013; Pecune et al., 2014). Thus, self-

disclosure of personal memories between patients and

caregivers helps staff personnel and informal care-

givers to improve their delivery of care, due to an im-

proved awareness of patients’ personal needs, and it

helps patients in developing a sense of companionship

and acceptance (Cooney et al., 2014; Haight et al.,

2006; Subramaniam and Woods, 2012; Subramaniam

et al., 2014; Thieme et al., 2011; van Gennip et al.,

2014).

Research suggests that the musical memory re-

mains largely unaffected in Alzheimer’s Disease.

This allows for the musical memory to act as a gate-

way to memories of lifetime events, even if such ac-

cess can no longer be achieved through a verbal route

(Clark and Warren, 2015; Cuddy and Duffin, 2005;

Cuddy et al., 2015; Jacobsen et al., 2015; Janata et al.,

2007; McDermott et al., 2014; Norman-Haignere

et al., 2015; Sarkamo et al., 2014; Schulkind and

Woldorf, 2005; Simmons-Stern et al., 2012; Sixsmith

and Gibson, 2007; Ueda et al., 2013; Vasionyte and

Madison, 2013). Therefore, to activate the patient’s

brain and autobiographical memory, ReMindMe uses

personalized music, which is to be provided by the

patient’s family and friends.

3 THE ReMindMe AGENT

Spoken language is the most natural way of commu-

nication, especially for people with Alzheimer’s dis-

ease. And so the ReMindMe agent will be capable of

engaging in vocal communication. The agent will use

either a NAO robot or a virtual agent for its body.

The ReMindMe agent engages in conversational

self-disclosure to develop its relationship with the pa-

tient. This means that the agent must itself be a

worthy interlocutor for people with Alzheimer’s dis-

ease, capable of developing and maintaining an equal,

confidential, and secure relationship with the patient

(Breazeal, 2004; Fiske, 1992).

Self-disclosure is expressed in the following

ways: (a) refer to mutual knowledge more often

(Planalp and Benson, 1992; Richards and Bransky,

2014); (b) share an increasing amount, breadth, and

depth of personal information (Bickmore et al., 2009;

Bickmore and Schulman, 2012; Collins and Miller,

1994); and (c) paraphrase the user’s utterances more

often (Cassell et al., 2007).

The extent to which the agent self-discloses

ICT4AWE 2016 - 2nd International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

62

Agent

Spoken

dialogue

Speech to text

Text to speech

User

Conversation state tracer

Start

.

..

...

End

Text interpreter

Domain knowledge

Xp2v

Xp2v

Xp2v

X

p

2

v

H3*s

H3*s

Conversation log

...

[actor][speech act]

...

H

3 2

p

v

X

?

*s

ReMindMe

H3*s

Knowledge representation

Dialogue planner

Conversation models

Conversation

state & discourse

Domain

knowledge

Sentence

constructions

Speech

acts

Xp2v= “I really like this song, it reminds me of my wedding”

H3*s = “Who did you marry?”

Figure 2: The ReMindMe architecture.

should gradually increase as the relationship ad-

vances. The ReMindMe agent will use a compu-

tational model to determine the appropriate level of

self-disclose. The level of self-disclosure is deter-

mined using a classification scheme by (Barak and

Gluck-Ofri, 2007). The agent reciprocates the user’s

level of self-disclosure by discussing only things

deemed appropriate for the topic and level of self-

disclosure chosen by the user.

Because of the reciprocal nature of self-

disclosure, the agent needs an identity and ‘personal

memories’ to be accepted as a worthy interlocutor.

The framework provides the agent with an identity

and memories by using fictitious ‘back stories’

(e.g. name, personal memories, favourite music).

Although one might find this deceitful, research sug-

gests people perceive this as engaging and enjoyable

(Bickmore et al., 2009).

4 PROPOSED RESEARCH

The ReMindMe architecture (also see Figure 2) de-

scribes a computational model that senses the cur-

rent relationship status and provides corresponding

self-disclosure speech acts (i.e., questions or ‘own’

experiences). The content, depth, and style of dia-

logue are derived from the domain knowledge repre-

sentation and prior conversations (i.e., ‘shared expe-

riences’) while maintaining conversational flow. The

architecture consists of the following components:

Text Interpreter. ReMindMe will use off-the-shelf

speech-to-text (Nuance’s Dragon) and text-to-speech

(Acapela) technology. A domain knowledge repre-

sentation will enable the agent to grasp the underlying

meaning of the user’s utterances. Example: The agent

grasps that this song is related to a happy memory of

the user’s wedding as it recognizes utterances ‘I like’,

‘song’, and ‘wedding’.

Domain Knowledge. The domain knowledge rep-

resentation - to be developed with the use of ontology

engineering (Noy and McGuinness, 2001; Peeters

et al., 2014b) - will contain general prior knowledge

about levels of self-disclosure, relationships, personal

memories, and music; and specific prior knowledge

about the agent’s back story. It will conversation, and

relationship. Example: the agent knows ‘wedding’

means ‘two people getting married’.

Conversation State Tracer. The state tracer will

keep track of the conversational discourse and state.

Example: The agent knows that ‘this song’ refers to

Elvis’ ‘Love me tender’.

Dialogue Planner. The dialogue planner will en-

able the agent to construct sentences that, i.a., (1)

self-disclose information, (2) ask questions, (3) para-

phrase the user, and (4) resolve miscommunication.

Example: The agent asks “Who did you marry?”

5 APPROACH

The ReMindMe system will be developed and eval-

uated by conducting a series of user-based studies

(see Table 1) following situated Cognitive Engineer-

ing (Neerincx and Lindenberg, 2008; Neerincx, 2011;

Peeters et al., 2012): a human-computer interaction

design methodology with a strong focus on theory de-

velopment through the systematic generation and test-

ing of hypotheses. To carefully handle privacy con-

siderations, the project will employ best practices of

Value-Sensitive Design (Friedman et al., 2013).

Participants. The target groups are (a) people with

mild to moderate dementia - as determined by de-

mentia care professionals -, and (b) their informal and

(c) professional caregivers. Participating patients still

live in their own homes and visit meeting centres on

ReMindMe: Agent-based Support for Self-disclosure of Personal Memories in People with Alzheimer’s Disease

63

Table 1: The research approach of ReMindMe.

Activity Description

Human-human study Patients and informal caregivers engage in conversation sessions* in mixed pairs.

Design conversation models Outcomes of the human-human study are used to model (1) conversation states and

transitions between them; (2) a set of appropriate speech acts for each conversa-

tional state; (3) sentence constructions for speech acts; and (4) a conversation log to

determine the conversational discourse.

Needs assessment All target groups participate in structured group interviews (Beer et al., 2012;

Peeters, 2014) at their meeting centres to obtain information about the needs of the

target groups in relation to personal memory support, and opportunities and require-

ments for a ReMindMe application to meet those needs.

Scripted human-human study Patients engage in single conversation sessions* with the experimenter, who strictly

follows the designed conversation models.

Adjust conversation models Adjust conversation models based on outcomes of scripted human-human study.

Design knowledge representation Design a domain knowledge representation based on outcomes of both non-scripted

and scripted human-human study, using ontology engineering (Noy and McGuin-

ness, 2001; Peeters et al., 2014b).

Wizard-of-oz study Patients participate in single conversation sessions* with the agent in a Wizard-of-

Oz set-up: unbeknown to the user, the experimenter simulates the agent’s behaviour

(Bernsen et al., 1994; Peeters et al., 2014a).

Expert review Dementia care professionals and clinical psychologists review the ontology follow-

ing an ontology review method, described in (Peeters et al., 2014b).

Adjust framework Adjust framework based on outcomes of Wizard-of-Oz study.

Implement prototype Implement prototype with the aid of a programmer.

Pilot study Patients participate in a run-through of the proof-of-concept evaluation to check the

experimental set-up and prototype usability.).

Adjust prototype Adjust prototype based on outcomes of pilot study.

Proof-of-concept study Patients engage in 12 conversation sessions* 2 or 3 days apart with the - fully im-

plemented and autonomously functioning - agent.

weekdays for daytime activities with other patients.

Patients with severe dementia may have difficulty en-

gaging with the agent, and so are excluded from par-

ticipation. People with dementia are a vulnerable tar-

get group, meaning careful attention is paid to ethical

conduct, e.g. informed consent and data storage.

* Conversation sessions - procedure. Patients

and their conversational partners (i.e. informal care-

giver, experimenter, or agent) take turns playing their

favourite music and asking each other about associ-

ated memories for 30 minutes at their regular meet-

ing centres. Participants are encouraged to follow up

on each other’s stories. During all sessions, a trusted

caregiver will be present to step in if needed.

6 CONCLUSION

This paper proposes the design and development

of an agent-based support system for people with

Alzheimer’s disease and their social environment,

called ReMindMe. The envisioned system will stim-

ulate patients to reminisce about personal memories

and engage in self-disclosure about those memories.

The agent itself will also be able to engage in con-

versations about personal memories with the patient,

thereby relieving from time to time the patients’ care-

givers. As the agent develops an equal, confidential,

and secure relationship with the patient, the agent can

serve as a trusted companion when the patient transi-

tions from the trusted home environment to a new care

facility. We expect that ReMindMe will greatly con-

tribute to the dementia care practice as a complemen-

tary tool that implements three effective psychosocial

interventions: trigger memory recall with the use of

music, reminiscence, and self-disclosure.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author would like to thank prof. Mark A. Neer-

incx, prof. Catholijn M. Jonker, dr. Koen V. Hindriks,

dr. Karel van den Bosch, and prof. Dirk K.J. Heylen

for their feedback on the ideas expressed in this paper.

ICT4AWE 2016 - 2nd International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

64

REFERENCES

Alzheimer’s Association (2015). Dementia - Signs, Symp-

toms, Causes, Tests, Treatment, Care.

Banerjee, S., Samsi, K., Petrie, C. D., Alvir, J., Treglia, M.,

Schwam, E. M., and del Valle, M. (2009). What do we

know about quality of life in dementia? A review of

the emerging evidence on the predictive and explana-

tory value of disease specific measures of health re-

lated quality of life in people with dementia. Interna-

tional Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 24(1):15–24.

Barak, A. and Gluck-Ofri, O. (2007). Degree and Reci-

procity of Self-Disclosure in Online Forums. Cy-

berPsychology & Behavior, 10(3):407–417.

Beer, J. M., Smarr, C.-A., Chen, T. L., Prakash, A., Mitzner,

T. L., Kemp, C. C., and Rogers, W. A. (2012). The

domesticated robot: design guidelines for assisting

older adults to age in place. In Proceedings of the an-

nual ACM/IEEE international conference on Human-

Robot Interaction, pages 335–342. ACM.

Bernsen, N. O., Dybkjær, H., and Dybkjær, L. (1994). Wiz-

ard of oz prototyping: How and when. Proc. CCI

Working Papers Cognit. Sci./HCI, Roskilde, Denmark.

Bickmore, T. and Schulman, D. (2012). Empirical vali-

dation of an accommodation theory-based model of

user-agent relationship. In Intelligent Virtual Agents,

pages 390–403. Springer.

Bickmore, T., Schulman, D., and Yin, L. (2009). En-

gagement vs. deceit: Virtual humans with human au-

tobiographies. In Proceedings of the International

Conference on Intelligent Virtual Agents, pages 6–19.

Springer.

Breazeal, C. (2004). Social Interactions in HRI: The Robot

View. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man and Cy-

bernetics, 34(2):181–186.

Cassell, J., Gill, A. J., and Tepper, P. A. (2007). Coordina-

tion in conversation and rapport. In Proceedings of the

workshop on Embodied Language Processing, pages

41–50. Association for Computational Linguistics.

Chan, D. K.-S. and Cheng, G. H.-L. (2004). A Comparison

of Offline and Online Friendship Qualities at Differ-

ent Stages of Relationship Development. Journal of

Social and Personal Relationships, 21(3):305–320.

Clark, C. C. and Warren, J. D. (2015). Music, mem-

ory and mechanisms in Alzheimers disease. Brain,

138(8):2122–2125.

Collins, N. L. and Miller, L. C. (1994). Self-disclosure and

liking: a meta-analytic review. Psychological bulletin,

116(3):457.

Cooney, A., Hunter, A., Murphy, K., Casey, D., Devane, D.,

Smyth, S., Dempsey, L., Murphy, E., Jordan, F., and

O’Shea, E. (2014). ‘Seeing me through my memo-

ries’: a grounded theory study on using reminiscence

with people with dementia living in long-term care.

Journal of Clinical Nursing, 23(23-24):3564–3574.

Cuddy, L. L. and Duffin, J. (2005). Music, memory, and

Alzheimer’s disease: is music recognition spared in

dementia, and how can it be assessed? Medical Hy-

potheses, 64(2):229–235.

Cuddy, L. L., Sikka, R., and Vanstone, A. (2015). Preser-

vation of musical memory and engagement in healthy

aging and Alzheimer’s disease: Musical memory in

Alzheimer’s disease. Annals of the New York Academy

of Sciences, 1337(1):223–231.

Derlega, V. J., Winstead, B. A., and Greene, K. (2008). Der-

lega et al. Self-disclosure and starting a close relation-

ship. In Sprecher, S., Wenzel, A., and Harvey, J., ed-

itors, Handbook of relationship initiation, pages 153–

174. Psychology Press, New York, NY, US.

Dindia, K., Allen, M., Preiss, R., Gayle, B., and Bur-

rell, N. (2002). Self-disclosure research: Knowl-

edge through meta-analysis. Interpersonal commu-

nication research: Advances through meta-analysis,

pages 169–185.

Dro

¨

es, R.-M., Boelens-van der Knoop, E. C. C., Bos,

J., Meihuizen, L., Ettema, T. P., Gerritsen, D.,

Hoogeveen, F., De Lange, J., and Scholzel-Dorenbos,

C. (2006). Quality of life in dementia in perspec-

tive - An explorative study of variations in opinions

among people with dementia and their professional

caregivers, and in literature. Dementia, 5(4):533–558.

Fiske, A. P. (1992). The Four Elementary Forms of Social-

ity: Framework for a Unified Theory of Social Rela-

tions. Psychological Review, 99(4):689–723.

Friedman, B., Kahn, Jr., P., Borning, A., and Huldtgren, A.

(2013). Value sensitive design and information sys-

tems. Early engagement and new technologies: Open-

ing up the laboratory, pages 55–95.

Greene, K., Derlega, V. J., and Mathews, A. (2006). Self

Disclosure in Personal Relationships. In The Cam-

bridge Handbook of Personal Relationships, pages

409–427. Cambridge University Press, New York,

NY, US.

Haight, B. K., Gibson, F., and Michel, Y. (2006). The

Northern Ireland life review/life storybook project

for people with dementia. Alzheimer’s & Dementia,

2(1):56–58.

Jacobsen, J.-H., Stelzer, J., Fritz, T. H., Chtelat, G., La Joie,

R., and Turner, R. (2015). Why musical memory can

be preserved in advanced Alzheimers disease. Brain,

138(8):2438–2450.

Janata, P., Tomic, S. T., and Rakowski, S. K. (2007). Char-

acterisation of music-evoked autobiographical memo-

ries. Memory, 15(8):845–860.

Koopmans, R., Olde Rikkert, M., and Zuidema, S. (2015).

Medicamenteuze behandeling van dementie. In Meer

kwaliteit van leven - Integratieve persoonsgerichte de-

mentiezorg, pages 47–63. Diagnosis Uitgevers, Leus-

den, the Netherlands.

Lawrence, V., Fossey, J., Ballard, C., Moniz-Cook, E., and

Murray, J. (2012). Improving quality of life for people

with dementia in care homes: making psychosocial

interventions work. The British Journal of Psychiatry,

201(5):344–351.

McDermott, O., Orrell, M., and Ridder, H. M. (2014). The

importance of music for people with dementia: the

perspectives of people with dementia, family carers,

staff and music therapists. Aging & Mental Health,

18(6):706–716.

ReMindMe: Agent-based Support for Self-disclosure of Personal Memories in People with Alzheimer’s Disease

65

Neerincx, M. A. (2011). Situated cognitive engineering for

crew support in space. Personal and Ubiquitous Com-

puting, 15(5):445–456.

Neerincx, M. A. and Lindenberg, J. (2008). Situated cogni-

tive engineering for complex task environments. In

Naturalistic Decision Making and Macrocognition,

pages 373–390. Ashgate.

Norman-Haignere, S., Kanwisher, N., and McDermott, J.

(2015). Distinct Cortical Pathways for Music and

Speech Revealed by Hypothesis-Free Voxel Decom-

position. Neuron, 88(6):1281–1296.

Noy, N. and McGuinness, D. (2001). Ontology Devel-

opment 101: A guide to creating your first ontol-

ogy. Technical report, Knowledge Systems Labora-

tory, Stanford University.

Pecune, F., Ochs, M., and Pelachaud, C. (2013). A Formal

Model of Social Relations for Artificial Companions.

In Proceedings of The European Workshop on Multi-

Agent Systems (EUMAS).

Pecune, F., Ochs, M., and Pelachaud, C. (2014). A Cog-

nitive Model of Social Relations for Artificial Com-

panions. In Intelligent Virtual Agents, pages 325–328.

Springer.

Peeters, M. M. M. (2014). Personalized Educational Games

- An agent-based architecture for automated scenario-

based training. PhD thesis, Utrecht University.

Peeters, M. M. M., van den Bosch, K., Meyer, J.-J. C.,

and Neerincx, M. A. (2012). Situated Cognitive En-

gineering: the Requirements and Design of Directed

Scenario-based Training. In Miller, L. and Roncagli-

olo, S., editors, Proceedings of the International Con-

ference on Advances in Computer-Human Interaction,

pages 266–272. Xpert Publishing Services.

Peeters, M. M. M., van den Bosch, K., Meyer, J.-J. C., and

Neerincx, M. A. (2014a). The Design and Effect of

Automated Directions During Scenario-based Train-

ing. Computers & Education, 70:173–183.

Peeters, M. M. M., van den Bosch, K., Neerincx, M. A.,

and Meyer, J.-J. C. (2014b). An Ontology for Auto-

mated Scenario-based Training. International Journal

of Technology Enhanced Learning, 6(3):195–211.

Planalp, S. and Benson, A. (1992). Friends’ and acquain-

tances’ conversations I: Perceived differences. Jour-

nal of Social and Personal Relationships, 9(4):483–

506.

Richards, D. and Bransky, K. (2014). ForgetMeNot:

What and how users expect intelligent virtual agents

to recall and forget personal conversational content.

International Journal of Human-Computer Studies,

72(5):460–476.

Riley, P., Alm, N., and Newell, A. (2009). An interactive

tool to promote musical creativity in people with de-

mentia. Computers in Human Behavior, 25(3):599–

608.

Sarkamo, T., Tervaniemi, M., Laitinen, S., Numminen, A.,

Kurki, M., Johnson, J. K., and Rantanen, P. (2014).

Cognitive, Emotional, and Social Benefits of Regular

Musical Activities in Early Dementia: Randomized

Controlled Study. The Gerontologist, 54(4):634–650.

Schulkind, M. D. and Woldorf, G. M. (2005). Emotional

organization of autobiographical memory. Memory &

cognition, 33(6):1025–1035.

Simmons-Stern, N. R., Deason, R. G., Brandler, B. J., Frus-

tace, B. S., O’Connor, M. K., Ally, B. A., and Budson,

A. E. (2012). Music-based memory enhancement in

Alzheimer’s Disease: Promise and limitations. Neu-

ropsychologia, 50(14):3295–3303.

Sixsmith, A. and Gibson, G. (2007). Music and the well-

being of people with dementia. Ageing and Society,

27(01):127.

Subramaniam, P. and Woods, B. (2012). The impact of indi-

vidual reminiscence therapy for people with dementia:

systematic review. Expert Review of Neurotherapeu-

tics, 12(5):545–555.

Subramaniam, P., Woods, B., and Whitaker, C. (2014). Life

review and life story books for people with mild to

moderate dementia: a randomised controlled trial. Ag-

ing & Mental Health, 18(3):363–375.

Thieme, A., Wallace, J., Thomas, J., Le Chen, K., Kr

¨

amer,

N., and Olivier, P. (2011). Lovers’ box: Designing for

reflection within romantic relationships. International

Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 69(5):283–297.

Ueda, T., Suzukamo, Y., Sato, M., and Izumi, S.-I. (2013).

Effects of music therapy on behavioral and psycholog-

ical symptoms of dementia: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. Ageing Research Reviews, 12(2):628–

641.

van Gennip, I. E., W. Pasman, H. R., Oosterveld-Vlug,

M. G., Willems, D. L., and Onwuteaka-Philipsen,

B. D. (2014). How Dementia Affects Personal Dig-

nity: A Qualitative Study on the Perspective of Indi-

viduals With Mild to Moderate Dementia. The Jour-

nals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences

and Social Sciences, pages 1–11.

Vasionyte, I. and Madison, G. (2013). Musical intervention

for patients with dementia: a meta-analysis. Journal

of Clinical Nursing, 22(9-10):1203–1216.

Verhey, F. (2015). Klachten en verschijnselen van demen-

tie. In Meer kwaliteit van leven - Integratieve per-

soonsgerichte dementiezorg, pages 163–184. Diagno-

sis Uitgevers, Leusden, the Netherlands.

Wallace, J., Thieme, A., Wood, G., Schofield, G., and

Olivier, P. (2012). Enabling self, intimacy and a sense

of home in dementia: an enquiry into design in a hos-

pital setting. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Confer-

ence on Human Factors in Computing Systems, pages

2629–2638. ACM.

World Health Organization (2015). WHO - Dementia.

ICT4AWE 2016 - 2nd International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

66