Nursing Documentation Improvement at Post-Acute Care Settings

Ryoma Seto

1

and Toshitaka Inoue

2,3

1

Division of Healthcare Informatics, Faculty of Healthcare, Tokyo Healthcare University, Tokyo, Japan

2

Dept. of Social Welfare Science, Faculty of Health and Social Welfare Science, Nishikyushu University, Saga, Japan

3

Seishinkai Inoue Hospital, Fukuoka, Japan

Keywords: Clinical Documentation Improvement, Electronic Health Records, Nursing Documentation, Patient Safety,

Vital Signs Documentation, Post-Acute Care Settings.

Abstract: Although nursing documentation is very important for patient safety, it forces nurses to spend increasing

amounts of their working time completing it. In this study, I evaluated the time lag between patient events to

completion of nursing documentation at two Post-Acute Care settings (called as “Care-Mixed Hospital” in

Japan, similar to nursing home). The mean time lag at Hospital A, which did not implement an automatic

documentation system (ADS) was 197.3 min [progress note regarding vital signs (VS), 208.2 min and the

others, 196.1 min. The mean time lag at Hospital B, which had implemented ADS, was 3.2 min (only

progress note regarding VS). ADS is effective in improving instantaneity on nursing documentation at post-

acute care settings.

1 INTRODUCTION

Nursing documentation is very important for

maintaining a good quality of nursing care.

Therefore, in previous studies, standardized

documentation forms were developed both in paper

and electronic formats (Romano, 1982). The

documentation framework (e.g., document form)

depends on the clinical situation and whether the

setting is clinical such as in an acute care facility or

community-based such as in a patient home. These

factors have an impact on how useful clinical data

can be collected (Curran, 1994). Therefore, nursing

documentation comprises various kinds of

documents that increase workload. Nursing

documentation is a significant proportion of the

workload that is associated with inpatient nursing care

(McCartney, 2013) (Asaro, 2003). It is unfortunate

that good documentation improves delivery of care

but creates a sub-optimal working environment for

clinical nurses at post-acute care settings.

To improve the situation, clinical document

improvement (CDI) was created. One of the most

popular CDI approaches involves the use of a

template. By using the template in the electric

medical record (EMR), nurses were able to reduce

their workload with respect to completing nursing

documentation (Richardson, 2015). The next CDI

approach used minimum data sets (MDSs). MDSs

comprised standardized data sets that can cover most

patients. In a previous study, MDS maintained the

quality of documentation and reduced the nurses’

workloads (Ranegger, 2015). Other CDI approaches

involve modifying the system design, which is time

consuming; therefore, early implementation is very

important (Read-Brown, 2013).

Moreover, secondary methods for nursing

documentation have rapidly spread. Needless to say,

nursing at post-acute care settings encompasses not

only the physical problems of the patient but also

psychosocial aspects. However, the patient’s

physiological symptoms are not easy to elucidate.

One study analyzed the patient’s physiological

requirements (Hill, 2015). Nursing documentation is

correlated with knowledge management. A study

analyzed the integration of narrative documents,

database storage, and connectivity with clinical

guidelines (Min, 2013). These challenges are

critically important to resolve; however, solutions

are only being trialed in a limited number of clinical

settings (e.g., university hospital and national

institutional hospital).

Nursing terminology comprises formal languages

and sub-languages (Mead, 1997). Nursing

terminology is complex. Furthermore, the quality of

nursing documentation may also be affected by

clinical governance regulations (Dehghan, 2013).

Therefore, CDI in nursing is a very long road.

Seto, R. and Inoue, T.

Nursing Documentation Improvement at Post-Acute Care Settings.

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health (ICT4AWE 2016), pages 163-168

ISBN: 978-989-758-180-9

Copyright

c

2016 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

163

However, CDI in nursing is one of the hottest

topics. Collins (Collins, 2013) noted that nursing

documentation patterns had been linked to the

patient’s mortality. In particular, vital signs (VS)

documentation is important. If the quality of VS

documentation is poor (delayed or incorrect), quick

responses to the patients’ requirements will be

difficult.

Overall, this study aims to elucidate the

effectiveness of CDI in nursing using the automatic

documentation system (ADS) at post-acute care

settings.

2 METHODS

2.1 Research Objectives

This study was performed at two post-acute care

settings. Both settings were very similar. The

settings (called as “Care-Mixed Hospital” in Japan,

but called as “Nursing Home” in the United States

and Europe) have 100–199 beds (this range of bed

numbers in the hospital represents the median of all

hospitals in Japan), including community care unit

(plans and implements follow-up care after

discharge).

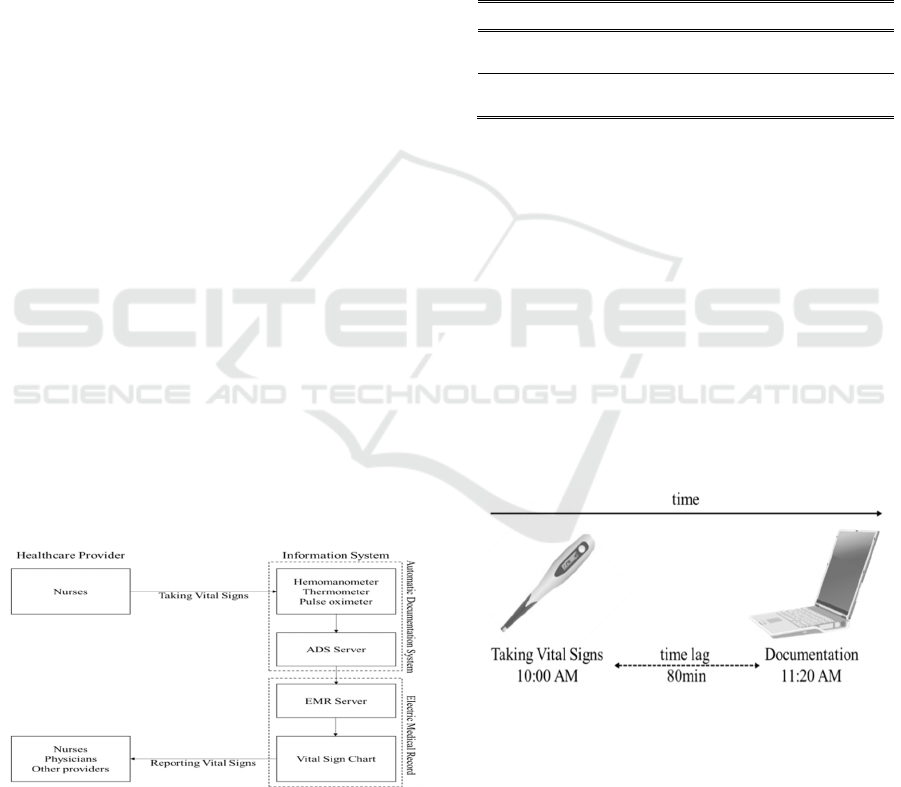

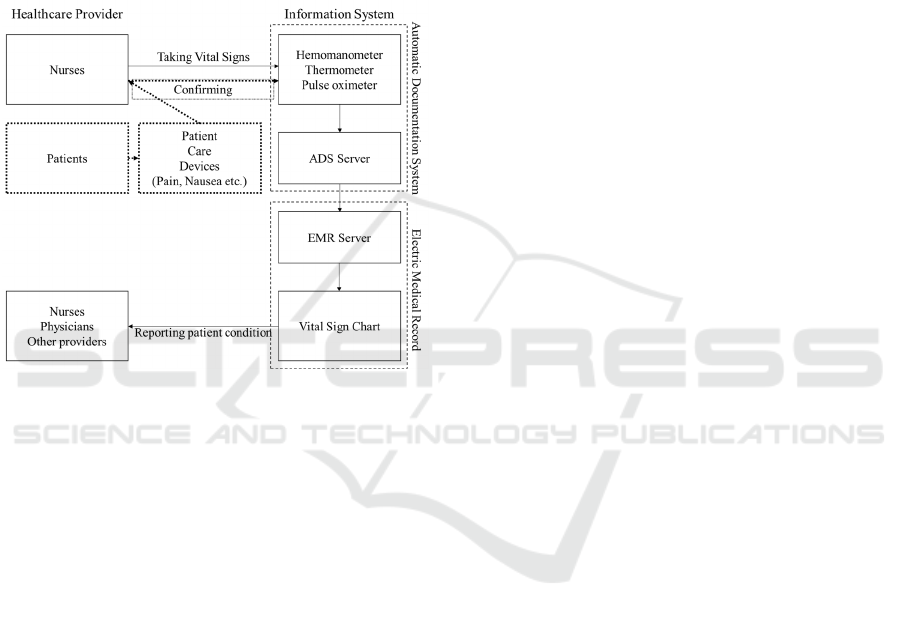

Hospital A implemented EMR but did not

implement ADS. Hospital B implemented both EMR

and ADS. ADS acts as a sub-system for the

automatic recording of VS, including body

temperature (BT), blood pressure (BP), and

pulse/SpO2, from an integrated VS recording

device, which includes a hemomanometer,

thermometer, and pulse oximeter. The devices flow

data to EMR (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Relation with EMR and ADS.

2.2 Data Collection

The research period was 5–6 months from July 2015

to September 2015.

At Hospital A, all nursing progress records of

24,355 patient–days were extracted from EMR.

Hospital A was selected for the “focus charting

method” using one of the nursing documentation

forms (e.g., SOAP). The charting method comprised

data collection on patient status and condition,

actions (interventions) by the nurse or other

healthcare provider, and responses of the patient

(Lampe, 1985) (Table 1). All progress notes were

distinguished from VS documentation or other

documentation using the text-mining methods.

Table 1: Overview of Documentation at Hospital A.

Focus Data Action Response

Lines

(per patient–day)

3.9 3.7 1.6 0.5

Characters

(per patient–day)

18.6 124.8 29.6 10.6

At Hospital B, data records of VS of 21,268

patient–day were extracted from the ADS server. On

an average, BP was recorded at 1.2 times/patient–

day, BT was 1.6 times/patient– day, and pulse/SpO2

was 1.4 times/patients–day.

2.3 Data Analysis

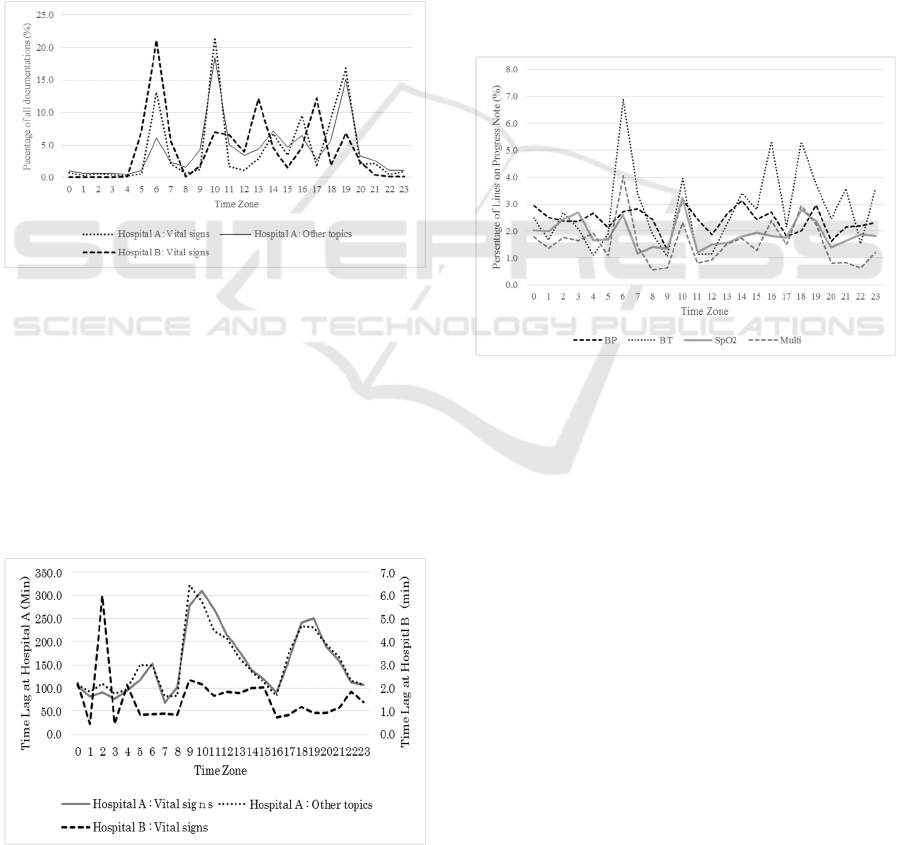

At both Hospitals A and B, the time lag between

patient events, nurses taking VS, and documentation

reaching EMR was calculated from the EMR system

log and/or ADS server (Fig. 2). Because previous

studies noted that CDI must create a considerably

busy working situation for nurses (Lees, 2010), time

lag was separated by time zone.

Figure 2: Example of Time Lag of Nursing

Documentation.

2.4 Ethical Consideration

This study was performed under national ethical

guidelines for epidemiological studies. All data of

nursing documentation was anonymized.

At Hospitals A and B, this study was approved

under the protocol for each hospital (CEO and/or

Management Board approved).

ICT4AWE 2016 - 2nd International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

164

3 RESULTS

3.1 Frequency of Taking Vital Signs by

Time Zone

The frequency of taking VS is shown by time zone

at each hospital (Fig. 3). Each hospital has three

peaks taking VS. The peaks at Hospital A occurred

at 6 AM (13.1%), 10 AM (21.5%), and 7 PM

(16.8%). The peaks at Hospital B were at 6 AM

(21.1%), 1 PM (12.1%), and 5 PM (12.2%). Taking

all of the documentation into account across all three

peak times at both the hospitals, 51.5% of all

documentation was completed at Hospital A and

45.4% was completed at Hospital B.

Figure 3: Frequency of Taking Vital Signs by Time Zone.

3.2 Time Lag between Taking VS and

Documentation

The time lag between taking VS and the nursing

documentation reaching EMR was 197.3 min at

Hospital A. VS documentation takes a significantly

longer time (p < 0.0001, Wilcoxon’s test) of 208.2

min to reach EMR than other documentations, which

only takes 196.1 min. The time lag at Hospital B

Figure 4: Time Lag between taking VS and ocumentation.

was just 3.2 min. The time lag by time zone is as

shown in Fig. 4.

The peak of time lag at Hospital A is shown at 6

AM (152.5 min), 10 AM (309.7 min), and 7 PM

(251.1 min); this peak is the same as the frequency

peak of taking VS. The peak of time lag at Hospital

B is shown at 2 AM (6.0 min) ; the peak differs from

the frequency peak of taking VS.

3.3 Content of Nursing Documentation

At Hospital A, all process records were analyzed;

which category does belong each lines of process

records. Of all process records, 2.6% were regarding

BP, 3.5% were regarding BT, 2.2% were SpO2,

1.9% were combined multiple source VS data (e.g.,

both BP and BT), and 89.8% were other parameters

(Fig. 5).

Figure 5: Contents of Nursing Documentation at Hospital

A.

For BP documentation, no peak of

documentation was observed. For BT documentation,

four peaks were observed at 6 AM (6.9% of all

documentation), 10 AM (3.9%), 4 PM (5.3%), and 6

PM (5.3%). For SpO2, two peaks were observed at

10 AM (3.2%) and 6 PM (2.8%).

4 DISCUSSION

4.1 Good Clinical Practice for

Collection of Vital Signs and

Accurate Completion of

Documentation

This study shows similar trends on taking VS at

Hospitals A and B because the frequency peak when

VS was taken at each hospital was the same. This

Nursing Documentation Improvement at Post-Acute Care Settings

165

trend may depend on the nurses’ working shifts: day,

8 AM–5 PM; evening, 4 PM–1 AM; and night, 0

AM–9 AM. Therefore, most nurses take VS as part

of their routine work schedule, i.e., twice during the

day and once in the evening and at night.

The importance of VS documentation has been

well discussed over the last 30 years (McCall, 1982).

In addition, precision in taking VS is very important

for maintaining the nursing quality of care. Missing

VS is a very serious omission; however, it occurs

from time to time (Grave, 2006). Therefore, to avoid

missing VS, we must discuss two issues (1) what is

the appropriate frequency for taking VS and (2) how

long does it take for this documentation to reach

EMR.

Issue (1) is not easy because the evidence for

proper frequency of taking VS is insufficient. In a

previous study, the frequency interval for measuring

VS was discussed at an emergency department (ED),

and BP documentation in ED was completed every

2.3 h for all patients (Miltner, 2014). Other studies

suggested that, complete VS documentation (BP, BT,

SpO2, and respirator rate) during every shift was

only completed for 17% of the recommended

intervals in 3 post-operative day (POD) and only for

5.6% in 7 POD (McGain, 2008).

In our study, VS was recorded every 4–9 h

during the day and 9–11 h during the night in

Hospitals A and B. This frequency of taking VS may

be sufficient, because the hospitals is post-acute care

settings.

Although Hospital A frequently measures VS,

the hospital has a huge risk of missing VS because

Hospital A has very long time lag (>3 h) between

taking VS and documentation reaching EMR.

Therefore, if a nurse at Hospital A takes VS in the

morning, other care staff will have VS of the patient

by afternoon. With respect to missing VS, it is

recommended not to clog the system with frequent

measuring of VS but to focus on improving the time

lag between measuring VS and documentation

reaching EMR at post-acute care settings.

4.2 Effectivity of Reducing Time Lag

using ADS

The solution for reducing missing VS has been

investigated in many studies. The basic approach is

to improve work flow on taking VS. In a previous

qualitative study, EMR was observed to be timelier

than paper-based documentation (Yeung, 2012). In

another study, user interface improvement on EMR

significantly reduced VS documentation but not

completely (Gerdtz, 2013). Whether VS

documentation is paper based or computerized and

PC based or tablet based, time lags will occur if

documentation is completed by people as opposed to

integrated data collection devices.

The second approach is role sharing. In a

previous study, routine observation and

documentation was performed by technicians (not

registered nurses) with tablet–PC (Wager, 2010).

Although effectiveness is limited, other benefits

could be considered because nurses at post-acute

care settings observe not only VS but other patient

parameters as well.

The third approach is integrating EMR and VS

recording devices. This approach was reported 10

years ago in the US, reducing nursing

documentation time (Arora, 2005). However, it is

very hard to use a VS monitor in all post-acute

patients. This policy of “automatic documentation”

is very realistic but an easier method is required in

the post-acute care setting as opposed to that

required for an ED.

In this study, it was found that ADS can reduce

time lag from 208.2 min to 3.2 min (98.5%). This

has a very clear and effective impact not only on

time lag but also on patient safety. Therefore, ADS

is strongly recommended to be implemented for

post-acute care settings as well as for EDs and acute

hospitals.

4.3 Maintaining Quality of Nursing

Documentation at Post-Acute Care

Settings

Reducing time lag is very important. Thus, we

should consider other types of documentation.

Our results demonstrated that the percentage of

VS documentation of all nursing documentation at

Hospital A was 10.2%. However, this rate varies

with time zone; nevertheless, the rate is part of the

routine workload schedule and is not affected by the

current patient conditions. Therefore, an ADS

system will not reduce the quality of documentation

on other aspects of patient care. Rather, currently,

many nurses cannot access patient information in a

timely manner because of the long time lag.

Although many nurses are forced to complete the

documentation, it may not be useful because it may

arrive in the system too late. This situation is known

as “death by data entry” and affects employees’

satisfaction (O’Brien, 2015).

VS are so fundamental that it should be

standardized. But other topics in post-acute care is

on progress in standardization. For example, in

oncology nursing at home, observation points were

ICT4AWE 2016 - 2nd International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

166

well discussed and standardized. A database system

that can improve nursing documentation has been

reported (Turner, 2015). Because standardization in

nursing is rapidly progressing, if technology could

be improved to measure other parameters associated

with patient subjective symptoms (e.g., nausea and

pain), ADS for post-acute care settings could be

utilized for a broader range of nursing

documentation that is designed in part with the

nurses’ input to maintain the quality of

documentation (Fig. 6).

Figure 6: ADS Scheme of the Future (For Post-Acute Care

Settings).

5 CONCLUSIONS

Nursing documentation without ADS has a very

long lag of over 3 h between the collection of VS

and reaching EMR. The current frequency intervals

of collecting VS are sufficient in the acute and post-

acute hospitals. Moreover, >10% of progress notes

contained information on VS.

As a means to improve patient safety in elderly

care, ADS is very effective and implementing it is

recommended even for use in post-acute care

facilities such as “Care-Mixed Hospital”, nursing

home and skilled care facility.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by a research grant of The

Health Care Science Institute, Japan.

REFERENCES

Romano C, McCormick KA, McNeely LD., 1982. Nursing

documentation: a model for a computerized data base.

ANS Adv Nurs Sci. Jan;4(2), pp.43-56.

Curran MA, Curran KE, Cody WK., 1994. Homeless

patients: designing a database for nursing

documentation. Proc Annu Symp Comput Appl Med

Care , pp.1017.

McCartney P., 2013, Evidence on electronic health record

documentation time. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs.

;38(2 ), pp.121.

Asaro PV, Boxerman SB., 2008. Effects of computerized

provider order entry and nursing documentation on

workflow. Acad Emerg Med ;15(10), pp.908-15.

Richardson KJ, Sengstack P, Doucette JN, Hammond WE,

Schertz M, Thompson J, Johnson C. 2015. Evaluation

of Nursing Documentation Completion of Stroke

Patients in the Emergency Department: A Pre-Post

Analysis Using Flowsheet. Comput Inform Nurs,

Epub.

Ranegger R, Hackl WO, Ammenwerth E., 2015.

Implementation of the Austrian Nursing Minimum

Data Set (NMDS-AT): A Feasibility Study. BMC Med

Inform Decis Mak. ;15(1), pp.75.

Read-Brown S, Sanders DS, Brown AS, Yackel TR, Choi

D, Tu DC, Chiang MF., 2013. Time-motion analysis of

clinical nursing documentation during implementation

of an electronic operating room management system

for ophthalmic surgery. AMIA Annu Symp Proc;

pp.1195-204.

Hill H, Evans JM, Forbat L., 2015. Nurses respond to

patients' psychosocial needs by dealing, ducking,

diverting and deferring: an observational study of a

hospice ward. BMC Nurs. ;14: 60.

Min YH, Park HA, Chung E, Lee H., 2013.

Implementation of a next-generation electronic

nursing records system based on detailed clinical

models and integration of clinical practice guidelines.

Healthc Inform Res.;19(4), pp.301-6.

Mead CN, Henry SB. 1997, Documenting 'what nurses

do'--moving beyond coding and classification. Proc

AMIA Annu Fall Symp. pp.141-5.

Dehghan M, Dehghan D, Sheikhrabori A, Sadeghi M,

Jalalian M., 2013. Quality improvement in clinical

documentation: does clinical governance work? J

Multidiscip Healthc. ; 6, pp.441-450.

Collins SA, Cato K, Albers D, Scott K, Stetson PD,

Bakken S, Vawdrey DK., 2013. Relationship between

nursing documentation and patients’ mortality. Am J

Crit Care ;22(4), pp.306-313.

Lampe SS., 1985. Focus charting: streamlining

documentation. Nurs Manage ; 16(7), pp.43-46.

Lees L., 2010. Improving the quality of nursing

documentation on an acute medicine unit. Nurs Times

;106(37), .22-26.

McCall P, O'Sullivan PS., 1982. Vital sign documentation

and primary nursing in the emergency department.

Emerg Nurs.; 8(4):187-90.

Nursing Documentation Improvement at Post-Acute Care Settings

167

Grave J, Opatrny J, Gouin S., 2006. High rate of missing

vital signs data at triage in a paediatric emergency

department. Paediatr Child Health; 11(4), 211-215.

Miltner RS, Johnson KD, Deierhoi R., 2014. Exploring the

frequency of blood pressure documentation in

emergency departments. J Nurs Scholarsh ;46(2),98-

105.

McGain F, Cretikos MA, Jones D, Van Dyk S, Buist MD,

2008. Opdam H, Pellegrino V, Robertson MS, Bellomo

R. Documentation of clinical review and vital signs

after major surgery. Med J Aust.; 189(7), .380-383.

Yeung MS, Lapinsky SE, Granton JT, Doran DM,

Cafazzo JA., 2012. Examining nursing vital signs

documentation workflow: barriers and oortunities in

general internal medicine units. J Clin Nurs; 21(7-8),

975-82.

Gerdtz MF, Waite R, Vassiliou T, Garbutt B., 2013.

Prematunga R, Virtue E. Evaluation of a multifaceted

intervention on documentation of vital signs at triage:

a before-and-after study. Emerg Med Australas. 25(6),

580-587.

Wager KA, Schaffner MJ, Foulois B, Swanson Kazley A,

Parker C, Walo H., 2010. Comparison of the quality

and timeliness of vital signs data using three different

data-entry devices. Comput Inform Nurs ;28(4), 205-

212.

Arora M, Falsafi N, Al-Ibrahim M, Sawyer R, Siegel E,

Joshi A, Finkelstein J., 2005. Evaluation of CoViSTA–

an Automated Vital Sign Documentation System–in an

Inpatient Hospital Setting. AMIA Annu Symroc; 2005:

885.

O’Brien A, Weaver C, Settergren TT, Hook ML, Ivory

CH., 2015. EHR Documentation: The Hype and the

Hope for Improving Nursing Satisfaction and Quality

Outcomes. Nurs Adm Q.; 39(4), .333-339.

Turner A, Stephenson M., 2015. Documentation of

chemotherapy administration by nursing staff in

inpatient and outpatient oncology/hematology

settings: a best practice implementation project. JBI

Database System Rev Implement Rep.; 13(10), .316-

334.

ICT4AWE 2016 - 2nd International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

168