A Practical Guide to Developing a Knowledge Management Culture

(KMC) in a Non-Profit Organization (NPO)

Tomasz Kampioni and Felicia Ciolfitto

The Law Society of British Columbia, 845 Cambie Street, Vancouver, BC V6Z 4Z9, Canada

Keywords: Knowledge Management Culture, Knowledge Management Project.

Abstract: Knowledge is the most important asset of an organization. Being able to preserve organizational knowledge

determines profitability, sustainability, competitiveness and the ability to grow. No organization can afford to

lose its knowledge base. According to the World Economy Forum, 95 percent of CEOs claim that Knowledge

Management (KM) is a critical factor in an organization’s success; and 80 percent of companies mentioned

in Fortune Magazine have staff assigned specifically to KM. Developing a culture of sharing and creating

knowledge is a long process that requires changing people’s values, beliefs and behaviours. Staff must be

convinced of KM benefits and be engaged in programs and initiatives that support transfer of knowledge.

Many organizations focus on technology as a silver bullet, losing sight of the fact that people as well as

processes are important factors in successful implementation of Knowledge Management Culture (KMC). In

this article we will discuss the concept of a knowledge management culture. We will specifically explore how

a non-profit organization (NPO) assessed its current environment and capitalized on its existing KMC as a

way to leverage its KM program. Creating a KMC is key since technology does not manage knowledge –

people do!

1 INTRODUCTION

Knowledge is a critical asset of any organization. It is

stored in documents, reports, organizational studies,

as well as in people’s heads. When an organization

loses an employee, it also loses any knowledge that

was not captured or transferred to other employees.

In the current competitive job market, staff

retention is one of the biggest challenges faced by

organizations. Dan Schwabel in the article: “The Top

10 Workplace Trends For 2014” points out that 73

percent of workers in the United States are either open

to hearing about or are looking for new employment.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics of United States

reports that people have about eleven jobs between

the ages of 18 and 34. Finally, 18 percent of boomers

will retire within five years (Schawbel, 2013). These

facts alone should encourage organizations to

develop KMC and promote capturing and sharing of

organizational knowledge.

In 2015, millennials will account for 36 percent of

the American workforce. One of the biggest problems

companies will have is succession planning.

Organizations have to develop knowledge transfer

programs and train the Gen X and Gen Y employees

before the boomers retire or they will be in major

trouble.

2 NON-PROFIT ORGANIZATION

The nature of a non-profit organization is to serve the

public for a defined purpose, without being profit

oriented. While the aim of for-profit organizations is

to maximize profits and forward these profits to the

company’s owners and shareholders, non-profit

organizations aim to provide for some aspect of

society’s needs. Despite these differences, both types

of organizations focus on improving staff

productivity, minimizing costs, introducing more

efficient and effective processes, as well as promoting

innovation, collaboration and the reuse of

information. Many organizations are already taking

advantage of KM programs to reach these objectives.

In 2014, the non-profit sector was the third largest

employer in United States. It included two million

non-profit organizations that employed 10.7 million

people and generated $1.9 trillion in revenue. Non-

profit organizations are projecting growth in 2015

Kampioni, T. and Ciolfitto, F..

A Practical Guide to Developing a Knowledge Management Culture (KMC) in a Non-Profit Organization (NPO).

In Proceedings of the 7th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management (IC3K 2015) - Volume 3: KMIS, pages 27-38

ISBN: 978-989-758-158-8

Copyright

c

2015 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

27

that could outpace the corporate sector. However, as

non-profits continue to grow, 90 percent of non-profit

organizations lack formal retention strategies,

succession planning and have no formal career paths

for the employees they would like to retain.

According to Nonprofit HR’s 2015 Nonprofit

Employment Practices Survey staff turnover in the

non-profit sector in 2014 reached 19 percent, and 14

percent of that was voluntary turnover. An increase in

voluntary turnover rate from 11 percent in 2012, and

10 percent in 2013, signals employees’ increased

confidence in the job market. An inability to pay

competitively and to promote staff, as well as

excessive workloads are the greatest retention

challenges faced by non-profits.

Organizations can't stop employees from leaving

unless they plan to entice them to stay. Even though

non-profit organizations are unable to pay

competitively, it turns out that compensation only

ranks 4th on the list of job satisfaction elements

according to 2014 SHRM Employee Satisfaction and

Engagement Survey. The top job satisfaction factor in

the survey was respectful treatment of all employees

at all levels and trust between employees and senior

management. The opportunity to use skills and

abilities in work ranked 6

th

and career advancement

opportunities within the organization and having

challenging, interesting and meaningful job were also

very important to employees. Keeping people

engaged and connected to the organization, as well as

providing environment to grow personally and

professionally while working on a variety of projects,

is the key to fostering employee commitment to the

organization’s mission.

The culture of the organization can certainly

contribute to whether an employee stays or leaves.

Non-profits need to make a conscious effort to engage

their employees from the recruitment process though

the reminder of the employment cycle in order to

retain these valuable resources. It is also critical to

provide staff with opportunities to learn new things

and make them feel that they are part of something

bigger.

KMC provides an environment for staff to acquire

new skills, to participate in mentoring and

apprenticeship programs and to work on cross

departmental projects in order to meet the

organizational objectives. Organizations are more

likely to retain employees who feel engaged and have

job satisfaction. KM programs contribute to high

levels of employee engagement, and, therefore,

greater staff retention.

3 ORGANIZATIONAL CULTURE

AND KNOWLEDGE

MANAGEMENT

Culture has been called the DNA of the organization.

It is about patterns of human interactions that are

often deeply ingrained. (Dalkir, 2011).

Organizational culture is composed of three building

blocks: values, beliefs and behavioural norms. Values

hold a central position in organizational culture. They

also reflect a person’s set of beliefs and assumptions

about external and internal environments. In addition,

they serve as the basis for the norms that underlie

behaviour. Organizational culture defines ways in

which people perform tasks, solve problems, resolve

conflicts, and treat customers or employees (Schein

1999). KM involves instilling certain kinds of values

in the organization. These values have at their core a

high appreciation and respect for individual

knowledge, as well as a commitment towards

fostering knowledge interactions through mutual

trust. An organizational culture that promotes KM is

founded on the perception that everyone stands to

gain by sharing and creating knowledge. It is a win-

win culture, in which both individuals and the

organization benefit.

In order to support a KM oriented culture, the

organization must develop shared values that promote

KM. Some of the values such as trust, respect for the

knowledge worker and identification with the

organizational goals, are universal KM values.

(Pasher and Ronen, 2011).

3.1 Misconceptions about Knowledge

Management

As you can imagine, a computer system cannot help

you to transfer tacit knowledge that is deep in

people’s minds into documented, explicit knowledge.

Technology, next to people and processes, is just one

of three components of KM. It is worth remembering

that KM programs should not be branded by their

technology applications. Wiki or Document

Management Systems (DMS) are just tools not brands

and they should never promote a KM program. It is

crucial to ensure that KM is seen as a holistic

approach enabled by dedicated employees, standard

processes and technology tools (O’Dell and Hubert,

2011).

The transfer of tacit knowledge usually occurs

when people work with other people and share their

knowledge. Psychologists have found that in face-to-

face talks, only 7 percent of the meaning is conveyed

KMIS 2015 - 7th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

28

by the words, while 38 percent is communicated by

intonation and 55 percent through visual cues, and up

to 87 percent of messages are interpreted on a

nonverbal, visual level (Mehrabian, 1972).

It is hard to deny the benefits of face-to-face

communication and transferring knowledge through

working together. KM programs must promote

interactions between employees but also provide

technology and support systems to capture acquired

knowledge. In addition, organizations must reward

employees’ contributions to the ongoing process of

capturing and preserving knowledge. The

participation of staff in KM programs is a key to the

development of a KMC in the organization. The

Pareto principle, also known as the 80–20 rule, states

that, for many events, roughly 80 percent of the

effects come from 20 percent of the causes (Reh

2005). When we look at the content contribution on

Facebook and Twitter, we notice that 80 percent of

content on Facebook is posted by 20 percent of the

users. Only one in five Twitter account holders has

ever posted anything, and 90 percent of content is

posted by 10 percent of the users (Moore 2010). We

should keep in mind these statistics while thinking

about participation rates for KM approaches using

Web 2.0 tools inside the organization. A small group

of people are the core contributors of content. The key

is to change this ratio and have more people creating

and capturing knowledge.

Developing and sustaining a KMC in an

organization is a challenging task that goes beyond

deploying a number of different applications and

systems. It is a complex process that relies on people

interacting with each other through face-to-face

programs, as well as online platforms. It also needs to

be supported by management and incentive programs

to keep the knowledge flowing through the

organization. Establishing KMC requires a project

management approach and all stakeholders must

understand what KMC is and its benefits. A KM

project team must develop a project plan and achieve

a number of milestones before completing the project.

The objective of this article is to provide guidance

on how to establish KMC in an organization. The

article captures the work, research and experiences

that led to introducing KMC in a NPO. However,

before we discuss our journey to KMC, we would like

to focus on the benefits of KMC and answer the

question ‘why’ organizations develop KM programs.

3.2 Benefits of a KMC

KM strategy must provide a balance between the

interactions of people and technology. KM is critical

to efficient operations, and a base for the continuous

development and improvement. A KMC offers

benefits in terms of succession planning and reduces

risk of organizational amnesia. In addition, KMC

provides quick and easy access to information and

consistency across the organization as well as

promotes reusing information and innovation.

3.2.1 Succession Planning

Losing an employee with years of experience can be

very disruptive to the operation of a particular

department, even to the entire organization. Tacit

knowledge that was never captured will be gone

forever. With the right programs in place, people’s

tacit knowledge can be documented and captured

providing a foundation and reference point for new

staff. Succession planning programs allow

organizations to reduce costs and help staff transition

to new positions without significant interruption in

business operations. Some organizations with strong

succession planning programs welcome rotation of

personnel as an opportunity for innovation, and for

bringing new energy and ideas to the organization.

3.2.2 Reducing Risk of Organizational

Amnesia

The National Aeronautic and Space Administration

(NASA) admitted that all the lessons learned and the

innovations that lead to successful landing on the

Moon cannot be found in the collective organizational

memory of NASA. This means that NASA’s

organizational memory cannot be used as a resource

to plan a more effective mission to send another

manned flight to the moon or to Mars (Dalkir, 2011).

Recreating the knowledge that has been lost is an

additional cost to the organization that a KMC could

have been prevented.

3.2.3 Quick and Easy Access to Information

RDMP Communications surveyed 100 UK

executives and found that more than half are unable

to access data they need largely because of "disparity

of data" and the "volume of data." That problem is

only increasing: Gartner Survey Results revealed that

"data volumes are increasing by over 75 percent every

year" (Gartner Press Release, 2014).

International Data Corporation’s (IDC) Content

Technologies Groups director, Susan Feldman (2004)

estimates that knowledge workers typically spend

from 15 to 35 percent of their time searching for

information. These workers typically succeed less

than 50 percent of the time. IDC estimates that 90

A Practical Guide to Developing a Knowledge Management Culture (KMC) in a Non-Profit Organization (NPO)

29

percent of a company’s accessible information is used

only once. The explicit knowledge that cannot be

found needs to be recreated resulting in time spent on

reworking it. The IDC study estimates that the

organization with one thousand knowledge workers

loses a minimum of $6 million per year in time spent

just searching for information. The cost of reworking

the information that was not found cost an additional

$12 million (Dalkir, 2011).

It is hard to estimate the loss of ideas that could

have been created based on the information that

should have be an easily accessible to the staff. Who

can afford to keep recreating what has been done

before? The idea is to move forward and build on

what has been already done instead of spending time

and effort on recreating the past.

3.2.4 Consistency Across the Organization

As a customer, getting two different answers to the

same question might be frustrating. From an

organization’s perspective, having customer

representatives misinforming clients can put its

reputation at risk, as well as present a liability risk.

Capturing and maintaining knowledge, as well as

providing staff with an easy access to the information

they need, ensures accuracy, professionalism and

results in customer satisfaction. However, having an

up-to-date KM information system depends on

people creating and updating the information. What

you put in is what you get out and people should be

aware of the importance of keeping the information

up to date as their colleagues rely on it.

3.2.5 Innovation

Innovation has three components: reuse of existing

organizational knowledge, creativity or invention,

and exploitation to create value. A balance between

these elements ensures that the knowledge is not

wasted, that the organization renews, and that

innovation has a business rationale. (Pasher and

Ronen, 2011).

Having a KMC in the organization and promoting

the transfer of knowledge between employees

stimulates innovation. KMC provides access to

lessons learned, results in conducted studies,

communities of practice, as well as collaboration

tools that allow people to share ideas and work

together on new products and services. Many

companies like Google or 3M grant their staff time

for innovation. Knowledge workers can use this time

for R&D ideas and work on whatever interests them.

Fifteen percent of the time that 3M employees spend

on innovation results in the development of new

products that account for 30 percent of sales. In

addition, the employees incorporate their own ideas

into creating value for the company.

There are many other benefits of having a KMC

that might be unique to specific industries or

organizations. It is worth noting that the benefits of

KM are relevant to all types of industries and all types

of organizations. Implementing KM must be a part of

the organizational strategy, and be strongly supported

by the CEO, and the executives and managers at all

levels of an organization.

4 A ROAD TO KNOWLEDGE

MANAGEMENT CULTURE

KM implies a strong tie to organizational goals and

strategy, and must be part of the organizational

vision, mission and strategic goals. It also must be

driven by executives whose involvement adds

credibility to KM programs and ensures the efforts

will last long term. Organizations with successful KM

programs have leaders from the CEO to mid-level

management, regularly reinforcing the need to share

and leverage knowledge. They consistently

communicate the value and importance of sharing and

reusing knowledge, which has a profound impact on

KM efforts. Leading by example means that the

executives and managers use the KM platforms to

generate and share knowledge as well as participate

in a variety of KM initiatives. Organizations that have

a knowledge-sharing culture have proven to be more

successful than the ones that do not. Employees who

collaborate and share knowledge are better at

achieving their work objectives, and do their jobs

more quickly and thoroughly (O’Dell and Hubert,

2011).

In our organization, the road to KMC started with

a CEO initiating the project, obtaining approval of the

Management Board, securing funding, and forming a

project team that was responsible for developing a

project plan based on organizational KM needs. The

role of the project team was to introduce a culture of

sharing the knowledge, and to develop supporting

KM programs and initiatives. The goal was to embed

KM into organizational values and peoples’ beliefs.

A project team had two years to establish a new

culture that promotes sharing knowledge, innovation

and organizational learning. In order to ensure

sustainability and grow of the KMC, it is best to

appoint a Chief Knowledge Officer (CKO) who

monitors and promotes the KM programs. The KM

project has goals, deliverables as well as an end date.

KMIS 2015 - 7th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

30

In contrast, KMC never ends, it’s an ongoing process

that becomes a big part of organizational DNA print.

4.1 Define KM Strategy

KM requires its own strategy that is based on

balancing people, processes and technology. A good

KM strategy should identify the key needs and issues

within the organization, and provide a framework to

address them. It is important to identify and prioritize

the knowledge required to immediately improve

performance and efficiency. The company should

focus its efforts of capturing the critical knowledge

that has the most value for the organization.

A KM strategy must be linked to the overall

business objectives of the organization. The two

mostly commonly encountered objectives of KM are

innovation and reuse. Innovation is linked to the

generation of new knowledge or new linkages

between existing knowledge. Reuse forms the basis

of organizational learning and should be viewed more

as a dissemination of innovation.

The most common business drivers that trigger a

need for KM are:

Retirement of key personnel;

Need for innovation to compete with other

organizations; and

Addressing internal inefficiencies to reduce

cost and improve the quality.

The KM strategy provides a foundation to

promote organizational learning, continuous

improvement and innovation. It is based on

organizational experiences both positive and negative

with the focus on avoiding the cost of redundant

efforts and designs, by not repeating the same

mistakes.

4.2 Business Case for KM

KM strategy must illustrate a solid business case that

identifies the benefits and costs of managing critical

knowledge. Introducing a KMC into an organization

is an expensive process and requires resources and

funding. A business case must evaluate the

opportunities of better knowledge flow through the

organization but also the costs, risks and resource

requirements associated with implementation of a

KMC. A business case should consider leveraging

existing infrastructures including technology and

programs that are already in place. This carefully

developed document contains a deeper understanding

of organizational knowledge assets and emphasizes

the value of the project and its implications. The

business case is a key document to obtaining

executive buy-in and funding.

4.3 Identify the KM Leader and

Project Team

Having the right leadership from the outset is the key

to success. Leadership creates vision and strategies

that management can then use to plan and budget.

Introducing a KMC into an organization should be

driven by the CEO or Executives of the organization.

They must understand the value of KMC and believe

that a KM program will help achieve the

organizational objectives.

Developing a KMC is a project that needs a skilful

project manager, diversified project team and

supporting sponsors that ensure funding and

resources for the project. The CEO or Executive team

are clearly the best candidates to be sponsors of the

KM project.

The Project Manager must have strong

communication and project management skills, as

well as a good understanding of the organization in

order to determine the knowledge needs and strategy.

The Project Manager plays a critical role not only

meeting project deadlines and objectives, but also in

changing organizational culture that will impact each

staff member.

The composition of the project team should

provide depth of skills and experiences. The KM core

group should include people from different

departments including Communications, Information

Services, Records Management and representatives

from business areas that generate critical

organizational knowledge. The project team should

also include a KM specialist who has skills and

experience in the discipline of KM and its approaches

(O’Dell and Hubert, 2011).

4.4 Assess Organizational Maturity

Level

Culture is a dynamic and fluid medium that changes

over time. It is a complex entity that changes within

an organization through the maturity process. As an

organization matures so does the culture of that

organization. Knowledge sharing practices are one of

many components of a maturing organizational

culture that needs to be monitored and supported to

reach higher levels.

Assessing a current KM maturity level of the

organization helps to identify strengths, gaps and

opportunities for improvement. It also helps to

anticipate how both the organization as a whole and

A Practical Guide to Developing a Knowledge Management Culture (KMC) in a Non-Profit Organization (NPO)

31

individual knowledge workers within that

organization will react to KM initiatives (Dalkir,

2011).

Table 1: KM Maturity Levels (Hubert, Lemons, 2010).

Level Description

1. Initiate: Growing

awareness

The organization is aware that it has a

problem retaining and sharing knowledge.

Senior leaders support testing a KM proof of

concept and creating KM strategy. KM

leader assesses current situation of

knowledge sharing in the organization,

potential barriers and existing KM

technology.

2. Develop:

Growing

Involvement

Initial knowledge approaches are in place.

The focus is on helping localized knowledge

flow and add value. The KM group has

identified improvement opportunities,

localized critical knowledge, conducted

needs assessment and knowledge gap

analysis.

3. Standardize:

Aligning processes

and approaches

The knowledge flow processes are

standardized and the focus is on meeting

organizational requirements, achieving

results, and developing a supporting

infrastructure. The organization has

developed KM approaches and supporting

tools. KM group has defined roles and

responsibilities.

4. Optimize: Driving

organizational

outcomes

KM efforts align with organizational

objectives and the focus is on leveraging

core knowledge assets across the enterprise.

KM strategy is treated as a core function

and integrates with enterprise strategy. KM

responsibilities factor into individual

performance assessment and are part of

talent management.

5. Innovate:

Continually

improving practices

KM practices are embedded in key

processes and the focus is on the

competency of the organization. Knowledge

flow in the organization supports innovation

and continuous improvement. KM is part of

part of an enterprise excellence framework

and has annual budget to support knowledge

sharing programs.

A good understanding of the level of maturity of

the organization helps in identifying the potential

enablers and obstacles to the organizational cultural

changes required for KM to succeed. It also helps to

determine types of initiatives and programs that have

to be created, as well as a level of knowledge support

that will be needed for effective KM programs to be

established within the organization.

The Maturity Model presented in Table 1,

characterizes different states of KMC associated with

each phase of organizational maturity. Using this

model, you can assess the current state of the

organization as well as define a desired maturity

level. An assessment helps to develop a roadmap and

focuses on tasks that need to be finished in order to

move to the next level. Skipping levels is not an

option. This is an organic growth process that requires

people to change their values, beliefs and behaviours.

Reaching for higher level of KM maturity, changes

organizational culture and it might present resistance

and challenges.

4.5 Identify the Problem

It is critical to identify the problem and ask “why” the

organization is introducing KMC. It is also important

to think in terms of strategic goals and then translate

them into operations (Sinek, 2011). Finally, it is

worth looking at the organization from the high level

perspective and understand how it operates. The

project team should consider both the short term and

long term implications. In addition, the project needs

to be scalable as its development and implementation

may occur over a multi-year horizon.

Conducting a needs assessment is a great place to

begin. It can also help focus on the nature of the

problem, and whether it is internal or external to the

organization. Internal is a good place to start because

the feedback provided can be immediate. As well, it

is good to conduct meetings with various departments

to figure out where the bottlenecks are.

The project team should identify existing

problems that need to be addressed and classify them

into main categories such as efficiency, effectiveness,

consistency and innovation. The audience affected by

the problem should also be defined, as well as

potential solutions and the priorities.

Table 2: Defining Problems and Solutions.

Problem Category Audience Solution Priority

4.6 Define the Scope of the Project

Keeping in mind the objectives of the project, and

budget and resource constrains, such as available staff

and time limitation, a list of specific project goals,

deliverables, tasks, costs and deadlines should be

developed. The project team must document which

deliverables are in the scope of the project and which

ones are out-of-scope. Setting project boundaries will

KMIS 2015 - 7th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

32

manage the expectations of the stakeholders and also

lower the risk of scope creep, which results in cost

overrun.

In project management, a project charter is a

statement of the scope, objectives, and participants in

a project. It provides a preliminary delineation of

roles and responsibilities, outlines the project

objectives, identifies the main stakeholders, and

defines the authority of the project manager. It serves

as a reference of authority for the future of the project.

4.7 Identify the Stakeholders

Project stakeholders are individuals that are actively

involved in the project, or whose interests may be

affected as a result of project execution or project

completion. They may also exert influence over the

project's objectives and outcomes.

Identifying all the stakeholders and getting them

on board early is key to a successful project. This is

important because change affects every stage of the

project from the initial evaluation stage to the

implementation and post implementation stage. The

needs assessment can be a good change agent in the

sense that it can assess the various stakeholders and

their positions, as well as the change and risk appetite.

It will also explain the rationale of the “why” of the

project.

It is really important to communicate the vision,

rationale and benefits to all stakeholders on an

ongoing basis. A project team must also identify and

recruit “champions”, seek out questions and answers

honestly, invite participation, acknowledge and deal

with rough spots, and be a role model.

One example that generated staff buy-in and

engagement was announcing a naming contest for the

KM program. In response, the project team got 170

name proposals that came from the staff of two

hundred. The project team understood that the award

was a key drive in contest participation but rewarding

people for their contributions will be an important

component of introducing and maintaining KMC in

the organization.

4.8 Evaluate Existing KM

Infrastructure

It is common to think that the new system will be a

saviour and that it is all technology based. But that is

not the case. In the first step, you should evaluate

existing programs and technology that could support

KMC.

The organization needs a holistic approach to

introducing and maintaining a KMC. There are a

number of different systems and programs that

support different functions of KM. They provide an

environment that encourages and makes knowledge

transfer possible.

Keeping in mind the project goals and

methodologies required to support the KMC, you

should evaluate programs and technology that are

already implemented in the organization. Your

objective should be to leverage existing programs and

infrastructure to establish and promote staff

participation in KM initiatives.

Below is a list of programs and initiatives

implemented by a mid-size organization to develop

its KMC. It could be used as a checklist for

developing KM infrastructure in any organization.

KM’s goal is to create and dismantle knowledge. In

order to achieve this objective, an organization needs

a variety of programs, methodologies and technology

to establish a knowledge culture supported by staff.

Organizational Values

Mandate and Mission Statement: clearly posted

and referenced so that staff are aware of what

they are working towards and how their role

fits within the organization and in the

achievement of the mandate and mission.

Building Relationships

Charity Fundraisers: staff hosted events to

benefit external organizations, but also bring

those within the organization closer through

working for a common cause;

Environmental Awareness Committee: staff

level committee to make improvements to the

organization so that it can be “greener”,

produce less waste and have an overall positive

effect on the environment;

Employee Council: staff level committee to

schedule group events, such as annual

barbecues and family events. It provides an

opportunity for staff to socialize outside of

work. As well, allows for suggestion box ideas

to be submitted and considered;

Informal Management Coffee Meetings: staff

level meetings that allow managers to socialize

with no set agenda;

CEO Breakfast: series of breakfast sessions

with CEO allowing staff to meet and talk to the

CEO in an informal environment and ask any

question they might have. It is also an

opportunity for the CEO to learn about the

challenges that staff faces on a daily basis;

Staff Forums: meetings with all employees and

presentation of key initiatives,

A Practical Guide to Developing a Knowledge Management Culture (KMC) in a Non-Profit Organization (NPO)

33

accomplishments and challenges. Staff Forums

are also focused on obtaining feedback from

staff through asking questions and short

workshop sessions.

Face-to-Face Knowledge Transfer Programs

Working Groups: staff level groups with clear

mandates for improving various organizational

functions or processes. This allows input from

various different departments and staff so that

all perspectives are considered;

Leadership Council: annual process of electing

three managers for one year term to work with

the Management Board to develop and ensure

implementation of operational initiatives in

fulfilment of the organization’s mandate and

strategic plan;

Employee Skills Enrichment Program:

specialized training provided by individuals

external to the organization on various topics,

such as, business relationships, leadership and

effective communication;

Job Shadowing: staff driven initiative which

allows staff to experience another position

within the organization first-hand and become

more familiar with the work involved and the

challenges therein. It helps build understanding

for what fellow co-workers do;

Secondments: management driven initiative

which allows staff to move into a temporarily

vacant position and expand their skill-set while

also offering value to the organization in terms

of reduced training costs and pre-existing

proprietary knowledge;

Breakfast Meetings Between Different

Departments: meetings with the focus on

identifying opportunities for improving

efficiency and enhancing processes. These

breakfast sessions have an informal

atmosphere but are focused on continuous

improvements;

Peer Review Sessions: an initiative where the

knowledge workers present their work,

including work in progress, and receive

feedback and ideas from their peers.

Technology

Customer and Client Database: databases

should be accessible to most internal

employees containing information on all

current and past customers/clients;

Document Management System: a central

repository system for all electronic documents;

Organizational Intranet: place for staff to

access relevant employee policy documents,

post a profile and get updates on news around

the organization;

Department-level Wiki: place to house

precedents or common questions encountered

by a particular department as a way to ensure

consistency;

Organizational Website: online presence

available to various internal and external

audiences which houses information on the

organization, and helpful forms and resources;

Knowledge Mapping (yellow pages): a

searchable online directory of staff profiles that

helps finding subject matter experts in the

organization;

Communities of Practice (forums, discussion

boards, blogs): online communities of people

with a common goal and a desire to share

experiences, insights, and best practices.

Developing Technical Core Competencies

Computer Literacy Program: provides training

to those who may need it to ensure that they are

comfortable with how to use the organization’s

computer systems and software;

In-house Training Program: regularly provides

training sessions on various topics of interest,

in terms of how to use certain program and

suggestions on how to become a more efficient

and savvy user;

Power Users: individuals within the

organization who are designated experts on

various technologies. They are able to assist

users who are not as familiar, or who may need

extra help;

IT Support: ongoing support from the

organizational IT team in terms of software and

hardware issues and questions.

Promoting Innovation Initiatives

Working Groups: allows the formation of

teams representing several areas of the

organization to come together and work on a

project that will be of benefit to the

organization;

Innovation Lottery: allows employees to

propose ideas for how to make their jobs and

the organization more effective and efficient;

Granting Time for Innovation: giving time to

employees to work on projects that interest

them, and to experiment and peruse new ideas

and solutions.

KMIS 2015 - 7th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

34

Recognising and Awarding Contributions

Bonus Program: annual program that

recognizes thriving professionals, and those

who perform above and beyond to help

advance the mandate of the organization;

Annual Recognition Awards: recognizes those

individuals who have made a particularly

important contribution that has resonated with

many areas of the organization.

Organizational Studies

Core Process Review: a way to map out what each

department does and how information flows between

them. Allows for recognition of any bottlenecks or

duplication of effort. Overall exercise in trying to

improve organizational efficiency;

Reports from Working Groups: a formal way to

present the work done by a working group and

share it with all staff and make clear

recommendations on how the organization

should proceed;

Interviews/surveys (both internal and external):

allows for the gathering of feedback as a way

to improve processes and also provide an

objective measure of how the organization is

doing in terms of its internal staff and external

customers/clients.

4.9 Implement Change Management

Introducing a KMC into an organization requires a

carefully planned change management process as it

will impact all employees within the organization and

possibly outside as well. As mentioned earlier,

starting with the “why” is important. Change

management requires an answer to the question of

“why” the organization is doing something.

People on all levels of the organization need to

understand the benefit of having well-establish KMC.

Without buy-in from the majority of staff, there is no

chance for successful implementation of a KMC.

In the end, all employees will be involved in an

ongoing process of creating knowledge and keeping

it up to date. Communication of the benefits of a

KMC is critical. In addition, programs need to be

established to support employees in the transition

to new information systems, and to ensure that they

feel confident using new technology. Staff should be

motivated and engaged in the process of creating and

maintaining organizational knowledge and to

participate in KM programs and initiatives.

5 LAUNCHING KM PROJECT

In the example discussed, the need to introduce a KM

program into the organization was identified by the

CEO. He got support for the project from the

Management Board and secured required resources

and funding. He was not only a project sponsor but

also a mentor and advocate of this initiative. His

involvement provided credibility and support for the

project among all employees of the organization. He

also appointed a project manager that would lead the

work of the KM team. Finally, the CEO was involved

in choosing the members of the project team ensuring

they have required skills and expertise to successfully

reach the objectives of the project.

Keeping in mind the mission and a vision

statement of the organization, a project team created

a mandate for the KM project that guided the team

through the process of establishing the KMC. The

first objective of our team was to identify where the

critical knowledge is generated, what problems

related to retaining this knowledge already existed,

who is affected by these problems and what possible

solutions could address the issues. This analysis

helped up to develop a business case with costs and

benefits of KMC, as well as a project plan with the

scope of work, deliverables, milestones, schedules,

required resources and a budget estimate.

The project team has also realized that staff might

not be familiar with the concept of KM. It was

decided that it would be beneficial to explain through

“lunch and learn” sessions what KM is and

communicate the objectives of the project. In order to

engage staff in the project, a contest for the name of

the KM program has been announced and many

employees submitted their proposals competing for

prize. Awarding contribution is an important element

of a KM program and the project team realized that a

recognition program must be in place to motivate

staff to share the knowledge.

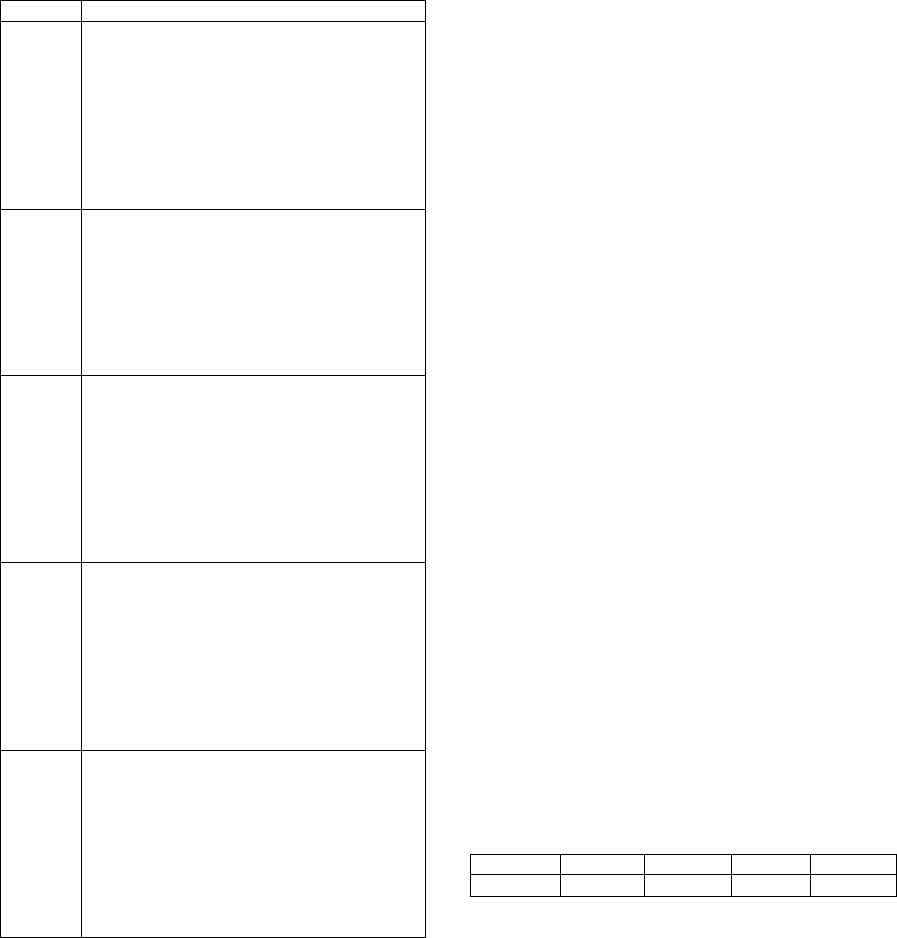

KMC requires a balanced approach. Our project

team identified five critical areas: people, programs,

technology, management and a reward system that

will help to determine successful implementation of

the project.

Figure 1 presents Kampioni’s KMC Self-

Assessment Wheel that allows you to evaluate, where

your organization is today. On a scale of one to five,

where one is developing and five is meeting the

criteria, asses all of the five major KMC components.

Connect the dots and see if you have an evenly

distributed chart. Keep in mind that an evenly inflated

wheel will keep your organization moving toward

higher levels of KMC.

A Practical Guide to Developing a Knowledge Management Culture (KMC) in a Non-Profit Organization (NPO)

35

Figure 1: Kampioni’s KMC Self-Assessment Wheel.

There is a misconception that KM is a new

technology that will be purchased and implemented.

Technology is a small part of KMC. It definitely helps

to manage explicit knowledge, but many programs

are required to transfer tacit knowledge that is deep in

people’s heads and can be transferred through

mentoring and apprenticeship programs, storytelling,

job shadowing and secondment policies.

Looking at the problem statement, the project

team grouped the issues that could be easily

addressed and those that would require more work.

The easy tasks were implemented early to give a

momentum to the project, generate awareness of the

benefits of KM, as well as get people’s buy in.

Changing the organizational culture and people’s

values and beliefs takes time, and must be supported

by evidence of benefits of the new approach.

Evaluation of existing KM infrastructure revealed

that the organization already had a strong KM

foundation. The project team focused its attention on

promoting existing KM programs, as well as

developing new ones. A Computer Literacy and

Skills Enrichment Program was designed to improve

peoples’ computer skills and to ensure that staff had

the skills and confidence to use KM systems. Staff

contributions determine the success of the program.

The project team gradually introduced new KM

technologies. In addition, each manager received KM

toolkit with tips and best practices to support KMC.

They very quickly embraced the role of leaders in

their respective operational areas and became KM

Champions.

The project team also looked into studies and

research of Jerome Bruner, an American psychologist

and educator whose work on perception, learning,

memory, and other aspects of cognition influenced

the American educational system. Jerome Bruner

developed a theory that people acquire knowledge,

when they actively participate and reason, rather than

passively absorb information, because this is what

gives knowledge meaning. In terms of cognitive

psychology, reasoning is seen as “processing

information," so the acquisition of knowledge should

be seen as a process, not a product or end result.

(Bruner 1990).

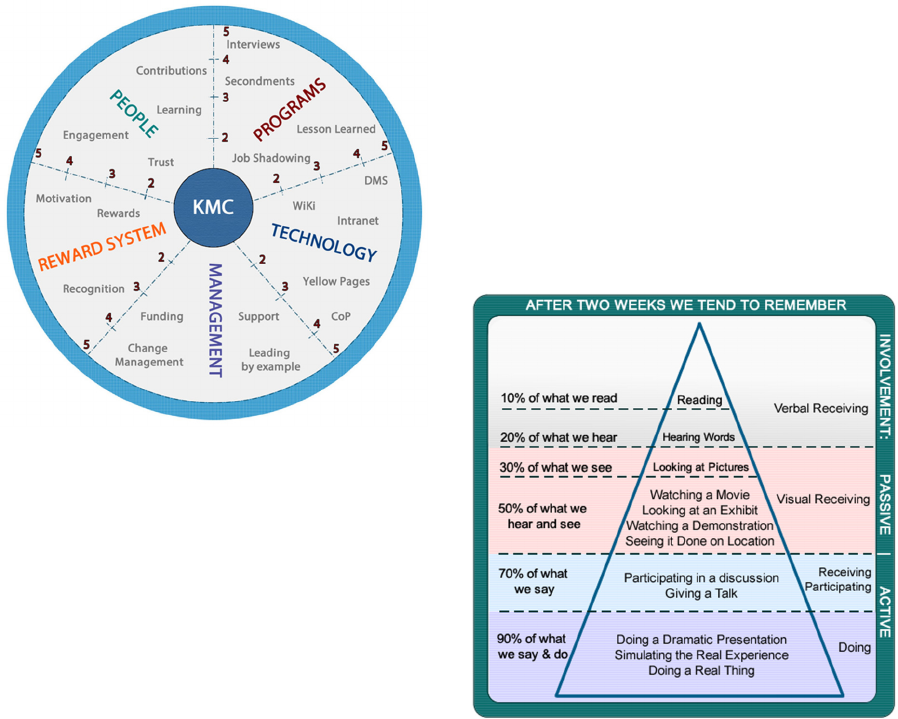

Figure 2: Dale’s Cone of Learning.

Edgar Dale’s study about the most effective methods

of learning influenced the project team to promote

and emphasize the importance of hands-on programs.

Dale theorized that learners retain more information

by what they do as opposed to what they read, hear or

observe. Dale’s Cone of Learning (Figure 2)

illustrates retention rates for different types of

learning (Dale 1969).

The project team also emphasized in its

communication to staff and managers that having a

KMC in the organization requires ongoing efforts of

all personnel, especially managers. KMC is not a

program with a completion date. The objective of a

KM project is to lay the foundation for KMC which

needs to be maintained, reviewed and promoted every

single day. This role should be assigned to the Chief

Knowledge Officer, who will monitor and promote

the program.

KMIS 2015 - 7th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

36

6 SUMMARY

Non-profit organizations face a great challenge to

retain their most talented employees. According to

Nonprofit HR’s “2015 National Nonprofit

Employment Practices Survey”, non-profit

organizations have experienced a 19 percent

employee turnover rate in the United States. Not

being able to pay competitively and provide

employees with formal career paths, as well as

excessive workloads, are the main reasons why

people move to the private sector. Although, the

results of a 2014 SHRM Employee Satisfaction and

Engagement Survey revealed that pay is important,

but it seems that organizational culture is even more

important. It turns out that the organizations that

provide an environment for learning and acquiring

new skills, which make people feel engaged and

respected, have better retention rates.

Organizations that have implemented KM

programs are proven to be more efficient and

effective, as well as more competitive and innovative.

These are essential characteristics for organizations to

ensure sustainability and growth in a dynamic

environment. KMC programs get staff involved in a

variety of projects, provide personal and professional

development opportunities, and make people feel

engaged and committed to the organization.

In the journey of introducing a KMC, we have

learned how important it is to generate awareness of

KM benefits among employees at all levels of the

organization. Being able to answer “why” we are

doing it, gets staff buy-in and engagement in the

processes of managing organizational knowledge.

Leadership must come from the CEO and

Executives, and has to be supported by managers at

all levels. A carriage without the horse won’t get you

far. The same rule applies to KMC without

management involvement. Staff participation in the

knowledge sharing programs is also a crucial factor

to keep KM initiatives alive.

Developing KMC is a complex process and

people must understand the value of maintaining this

culture. Leadership can come from the top, but

advocates of sustaining a knowledge-sharing culture

should be at all levels of the organization regardless

of their official job titles.

In KMC each person is a contributor and benefits

from the work of other people. Having easy access to

up-to-date information benefits employees, as well as

the organization; therefore, each person should take

responsibility for maintaining the information that

other people rely upon.

People, processes and technology are three major

components of KM. They are equally important in the

process of managing knowledge. Technology

provides infrastructure and people generate content.

Processes and different programs stimulate the flow

and transfer of knowledge. However, selection of the

right programs and technology is very important so as

not to overwhelm people.

Clifford Nass, a professor at Stanford University,

predicted that multitaskers might be good at filtering

information, switching quickly between tasks and

organizing their memories to ensure that the

important facts are retained. However, his research

results indicated the opposite: “It turns out that

multitaskers are terrible at every aspect of

multitasking” (Eyal, Nass, and Wagner, 2009). HP

research indicates that employees that were

interrupted by e-mail or instant messages, needed on

average of 15 minutes to fully reset their focus and go

back to the state of deep thinking they were before the

interruption occurred (Lapowsky, 2013). These

studies should be taken into consideration before

introducing new technology. Each program should be

carefully evaluated before rolling it out to all staff.

The goal is to focus on developing an infrastructure

to capture and share knowledge without causing

productivity loss and frustration.

KM requires its own strategy that must support

organizational objectives. A strong business case that

emphasizes costs and benefits of implementing KMC

will get executive support and funding. Once the

project is approved, a project team must be

established. The composition of the KM team is

critical for the success of the project. A results-

oriented KM project manager should lead the team

containing members from different departments, as

well as a KM specialist that is aware of KM

approaches and methodologies. In the first step, the

project team must develop an achievable project plan.

It is important to focus on the critical knowledge and

identify where it is generated and understand how to

retain it. Considering project goals, budget and

available resources, a project scope has to be

determined. It will provide guidance for the project

team and ensure that each member works towards

established goals and objectives.

An assessment and evaluation of existing KM

infrastructure that includes programs, processes and

technology is a good starting point to develop a

project plan and determine the scope of work. New

KM platforms and technology might be expensive so

it’s worth considering leveraging existing

infrastructure. However, all stakeholders should be

aware that KM is not about technology, but about

A Practical Guide to Developing a Knowledge Management Culture (KMC) in a Non-Profit Organization (NPO)

37

staff capturing and sharing knowledge. People must

understand the value of efforts to preserve

knowledge. A collaborative environment, where

people learn from each other and increase their

knowledge has been proven to be more productive

and attractive to staff. When staff are happy, good

things happen for the organization.

It has been proven that we learn by working

together and the organization should endorse face-to-

face programs that promote better knowledge flow

among staff. According to a Harvard study, when

face-to-face interaction is used retention of

transferred knowledge increases to 71 percent.

Further, when visuals are used 28 percent less time is

consumed (Tinto, 2006). Succession planning, job

shadowing, interviews, secondments and peer review

sessions are examples of effective face-to-face

programs that through their mentoring and

apprenticeship style have proven to be very

successful. The organization should ensure that these

programs exist and people are aware of them and are

encouraged to participate in them.

KM promotes the reuse of information and

innovation. This makes the organization efficient and

more competitive. Initiatives that promote building

relationships, reward people for their contributions,

and allow staff to work on cross departmental

projects, stimulate the flow of knowledge and

learning. Building a KM oriented culture in the

organization is an ongoing process that requires a

variety of programs and tools, as well as management

support. It takes time for the organization to reach the

highest level of KM maturity. It will take a lot of

effort to maintain this level of engagement. However,

the benefits of KMC, and the resulting satisfaction

and productivity of staff, are encouraging factors that

will help staff to embrace the challenge of introducing

and maintaining KMC in the organization.

REFERENCES

Brown, J.S., Duguid, P., 1998. Organizing Knowledge,

California Management Review Vol. 40, No. 3.

Bruner, J., 1990. Acts of Meaning, Hebrew University of

Jerusalem and Harvard University Press.

Dale, E., 1969. Audio-Visual Methods in Teaching, Holt,

Rinehart & Winston, New York.

Dalkir, K., 2011. Knowledge Management in Theory and

Practice, The MIT Press. Cambridge, Massachusetts

London, England. 2nd edition.

Davenport, T.H., Prusak, L., 2000. Working Knowledge,

Harvard Business School Press. Harvard.

Duffy, J., 2001. The Tools and Technologies Needed for

Knowledge Management, Information Management

Journal, Prairie Village, Vol. 35, No. 1" 2001.

Eyal, O., Nass, C., Wagner, A., 2009. Cognitive Control in

Media Multitaskers, PNAS: Proceedings of the

National Academy of Sciences, August 24, 2009.

Gartner Press Release, 2014. Gartner Survey Reveals That

73 Percent of Organizations Have Invested or Plan to

Invest in Big Data in the Next Two Years, Stamford,

http://www.gartner.com/newsroom/id/2848718.

Geisler, E., Wickramasinghe, N., 2015. Principles of

knowledge management, Routledge. New York, NY.

Hubert, C., Lemons, D., 2010. APQC's levels of knowledge

management maturity. APQC. 2010:1-5.

Kotter, J., 1996. Leading Change, Harvard Business

Review Press. Harvard.

Lapowsky, I., 2013. Don’t Multitask: Your Brain Will

Thank You, Time Magazine, Vol. 181, No. 13".

Lee, J., 2000. Knowledge Management: The Intellectual

Revolution, IIE Solutions, Norcross, Vol. 32, No. 10".

Mehrabian, A., 1972. Nonverbal communication. Aldine-

Atherton, Chicago.

Moore, R., 2010. New Data on Twitter’s Users and

Engagement. RJMetrics, January 26.

Nonprofit HR and Improve Group, 2015. The 2015

National Nonprofit Employment Practices Survey.

O'Dell, C., Hubert C., 2011. The New Edge in Knowledge,

John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Hoboken, New Jersey.

Pasher, E., Ronen, T., 2011. The complete guide to

Knowledge Management, John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Hoboken, New Jersey.

Reh, F., 2005. Pareto's Principle - The 80-20 Rule. Business

Credit 107.7 (Jul/Aug 2005): 76.

Schawbel, D., 2013. The Top 10 Workplace Trends For

2014, Forbes, Oct 24, 2013.

Schein, E., 1999. The corporate culture survival guide:

Sense and nonsense about cultural change. San

Francisco: Jossey Bass.

Sinek, S., 2011. Start with the Why, The Penguin Group.

London.

The Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM),

2015. A 2014 Employee Job Satisfaction and

Engagement Survey

.

Tinto, V., 2006. Research and Practice of Student

Retention: What Next? Journal of College Student

Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, May 2006.

KMIS 2015 - 7th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

38