Business Model Framework to Provide Heterogeneous Mobility Services

on Virtual Markets

Markus C. Beutel

1

, Christian Samsel

1

, Matthias Mensing

2

and Karl-Heinz Krempels

1

1

Information Systems, RWTH Aachen University, Aachen, Germany

2

Economic Geography of Services, RWTH Aachen University, Aachen, Germany

Keywords:

Virtual Market, Virtual Currency, Business Model, Mobility, Incentives.

Abstract:

Growing spontaneous mobility and decreasing affinity to automobile ownership in younger generations de-

mand for an integrated service for intermodal mobility. In areas with lacking coverage of traditional public

transportation, extending the coverage by integrating alternative services like car sharing, seems promising.

Because of the very different nature, the collaboration between traditional public transport and emerging mo-

bility services requires fundamental changes to business models. Current business models are designed under

the assumption of separation and competition, which contradicts the idea of collaboration. Therefore, arestruc-

turing of all main pillars of business models under the consideration of mutual interdependencies is required.

This work defines such business model pillars and contributes a business model framework for providing dif-

ferent mobility services on centralized virtual markets. Basis is a joint platform which enables collaboration

between multiple services to provide a collective intermodal mobility service to the customer.

1 INTRODUCTION

Currently, different means of transportation are usu-

ally seen as mutual exclusive alternatives, people

travel either by train or by bus. Global trends like de-

creasing importance of private automobile ownership

(Bentenrieder, 2010) and oil peak demand a changing

understanding of peoples transportation. To increas-

ing efficiency an integrated view of mobility services

is required. E.g, there are regions which are not cov-

ered by traditional public transport modes adequately,

alternatives like car sharing can close these gaps and,

in combination with traditional public transportation,

ensure service coverage. To offer a joint service con-

sisting of different modes to customer, an encompass-

ing business model, which sets incentives for users

to change their mobility behavior, is required. Be-

cause of its big potential concerning mobility service

coverage we focus especially on an incentive oriented

integration of car pooling.

Information Broker

This investigation prescinds from discussing the ad-

vantages and disadvantages of collaborative mobil-

ity service provision, but shows the required and op-

tional shifts in business models within this scenario.

Thus, the approach is based on the assumption of a

collaborating mobility provider network. The basis

for collaboration is a joint software system that cen-

trally bundles information of various mobility service

providers with diverse modalities. For the following,

we call this platform InformationBroker (IB). The In-

formation Broker is supposed to be operated by a third

party organization which does not offer mobility ser-

vices itself, to ensure undiscriminated system access.

The IB combines the information and services (e.g.,

train timetables, carsharing sites) of all involved mo-

bility service providers to generate the best possible

intermodal itineraries. In terms of technology we as-

sume this is realizable. General distributed architec-

tures, methods for data integration and routing algo-

rithms are well-known. One crucial aspect is the data

exchange between IB and mobility service providers.

This can be handled by existing protocols, e.g., SIRI

1

a protocol to allow exchange information about pub-

lic transport services and vehicles, standardized by

the CEN (European Committee for Standardization).

For sharing modes, e.g. carsharing, IXSI

2

(Interface

for X-Sharing Information) has been developed and

1

http://user47094.vs.easily.co.uk/siri/

2

http://ixsi-schnittstelle.de

145

Beutel M., Samsel C., Mensing M. and Krempels K..

Business Model Framework to Provide Heterogeneous Mobility Services on Virtual Markets.

DOI: 10.5220/0005118601450151

In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on e-Business (ICE-B-2014), pages 145-151

ISBN: 978-989-758-043-7

Copyright

c

2014 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

tested in project econnect Germany

3

.

There is already a variety of software systems that

integrate different modalities (Beutel and Krempels,

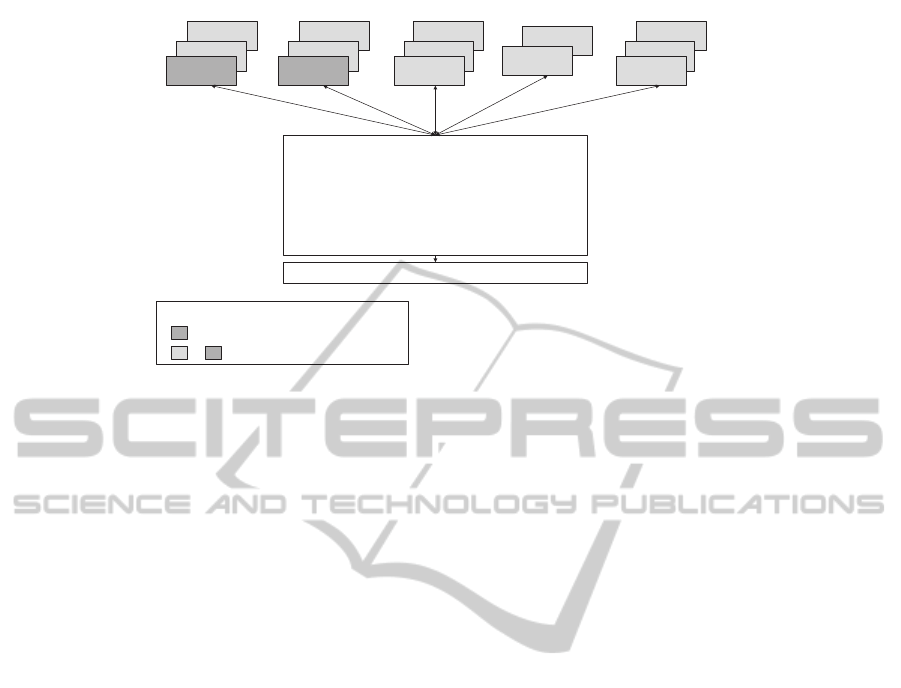

2014). 1 illustrates the extent of the IB, which is de-

scribed in this work compared to the existing software

DB Navigator/bahn.de by Deutsche Bahn AG

4

. The

IB includes modes like car pooling and additional ser-

vices, e.g., parking.

Electronic Ticketing

To offer a combined ticket for intermodal travel, a

technological realization is required. Currently, mul-

tiple standards for electronic tickets have been de-

veloped and deployed. Prominent examples are the

(((eTicket

5

, which is the de facto standard in Ger-

many, and Calypso

6

, which is in use in several Eu-

ropean cities. Currently a suppose-to-be continent

wide standard is being developed under the name IFM

Project

7

. Each of them is based on contact-free smart

cards. We suppose these electronic tickets are suit-

able for most, if not all, mobility modes and therefore

allow a combined ticket.

The remainder of this paper is structured as fol-

lows: 2 gives an overview over the theoretical back-

ground and previous work concerning business mod-

els and cooperation schemes. 3 defines business

model pillars for the context of providing mobility

services on virtual markets. Finally, 4 concludes work

and gives an outlook on future work.

2 BUSINESS MODEL THEORY

Reviewing the literature about the emergence of busi-

ness models with focus on e-business and informa-

tion system implementation, a large variety of dif-

ferent business model frameworks can be observed

(Timmers, 1998) (Osterwalder et al., 2005) (Silver,

2007). Most of previous studies focus on the value

creation process of Porter’s value chain logic and sep-

arate this process into “building blocks” (Osterwalder

et al., 2005) which can be identified in all organi-

zations. However, (Veit et al., 2014) conclude that

business models are dependent on the industry and

the context they are applied in. In the case of pro-

viding heterogeneous intermodal mobility modes via

3

http://www.econnect-germany.de

4

http://www.bahn.de/p/view/buchung/mobil/

dbnavigator.Shtml

5

http://www.eticket-deutschland.de

6

http://www.calypsonet-asso.org

7

http://www.ifm-project.eu

information systems, existing business models fail to

address key aspects in this context. Thus, we con-

centrate on essential parts of common business mod-

els and expand the understanding by introducing new

features to the existing logic of e-business models.

The ability to create value for the target customer

from products and services depends on the value

proposition the organization is willing or able to of-

fer and its ability and capacity to innovate and hence

to differentiate. The value proposition correlates with

the firms’ capability to offer better solutions meet-

ing customer needs in comparison to its competitors

(Johnson et al., 2008). Higher value proposition can

be achieved by customization of goods, lower prices

by reducing costs or provision of superior service to

the customer (Osterwalder et al., 2005). To effectively

deliver the value proposition offered to the customer,

the firm needs to define its geographical extent of the

market area, target customers and offered products to

delineate the value proposition from its competitors

(Afuah and Tucci, 2000). To ensure the delivery of

the value to the customer, the firm requires capabil-

ities organized in the value chain like value creating

activities, partner networks or resources.

To analyze key activities of companies provid-

ing mobility services we refer to the traditional value

chain model by (Porter, 1985) as it is the standard tool

used in academia and business. The value chain is a

method in strategic planning used to identify the com-

petitive advantage of firms. It focuses on the inves-

tigation of the critical activities connecting the sup-

ply and demand side of organizations and aims at an

understanding of their impacts on value and cost of

offered products. Activities of the value chain can

be organized internally within the firm or externally

by partners. The value chain concept also created a

framework for a value definition and comprehension

about the way value is created (Peppard and Rylander,

2006). The definition of value is simply the willing-

ness to pay for a productwhich is offeredvia the value

chain to the customer.

(Porter and Millar, 1985) come to the conclusion

that information systems “transform” the value chain

since they are present at all stages of value creat-

ing activities, but not as a potential source of value.

(Rayport and Sviokla, 1995) expand the understand-

ing of the role of information systems in value chain

modeling by developing the concept of “virtual value

chains”. Virtual value chains are based on informa-

tion accessibility. All activities facilitating the gather-

ing, organizing, selecting, synthesizing and distribut-

ing of information increase the effectiveness and ef-

ficiency of mediating between the traditional value

chain activities (Chaffey, 2009). Hence, information

ICE-B2014-InternationalConferenceone-Business

146

Legend

+

Train Bus Car/ Bike

Sharing

Car Pooling Parking

...

Provider B

Provider A

...

Provider B

Provider A

...

Provider B

Provider A

...

User A

One Ticket

Intermodal Routing

Market Place

Accounting

Currency Management

...

Provider B

Provider A

DB Navigator Extent

Information Broker Extent

Information

Broker (IB)

Figure 1: DB Navigator / bahn.de versus Information Broker Software Extent.

systems involving electronic commerce can add value

to the internal and external value chain.

The value chain model so far explained has been

a firm and product centric approach to determine the

underlying value adding activities of organizations.

(Stabell and Fjeldstad, 1998) argue that the traditional

value chain analysis cannot be applied to all types

of businesses. On the one hand value adding activ-

ities in, e.g., the generation of services are funda-

mentally different from the manufacturing of tangible

goods. On the other hand scholars realized that or-

ganizations are embedded in complex economic net-

works (Easton, 1992). Hence, Stabell and Fjeldstad

developed the “value network” as an extension of

Porter’s “value chains” incorporating the above men-

tioned shortcomings. This approach shifts the in-

vestigation perspective away from a resource based

view of the focal company to a more holistic view

of evaluating resource dependency, transaction costs

and actor-network relationships in the network of

the industry (Basole and Rouse, 2008). Value net-

works are composed of connected and interdependent

players. These players interact with the other mem-

bers of the network and their relationships have di-

rect consequences for the whole network performance

(H˚a kansson et al., 2009). Since the members of the

network have different assets and competences their

goal is to co-create value by collaboration. Hence,

value is created not from one firm but by an efficient

interplay of all members of the network (Vanhaver-

beke and Cloodt, 2006). In contrast to the value chain

logic competitive advantage is no longer created at the

single focal company but originates from the constel-

lation of the available value of the network partners

(Gomes-Casseres, 1994). The inter-firm relationships

can manifest in several forms, including alliances, eq-

uity investment, partnerships, joint ventures, consor-

tia, marketing agreements, licensing, supply agree-

ments and manufacturing agreements (Gulati et al.,

2000), (Podolny, 1998). The decision to agree to one

of the above mentioned relationships is strategically

(Doz and Hamel, 1998). Motives to join several rela-

tionships are: access to new markets, technology and

knowledge they need to innovate (Ahuja, 2000), the

reduction of external risk (Pfeffer and Nowak, 1976)

or regulatory requirements (Oliver, 1990). However,

collaboration can has its own risks, since all players

in the value network can act opportunistic, thus shar-

ing not the goal to maximize the overall value. Trust

is the fundamental condition for effective collabora-

tion in value networks (Faber et al., 2003). Earning

the trust of the costumer is another fundamental pillar

of the business model ontology proposed by (Oster-

walder et al., 2002). They refer to it as relationship

capital. Trust is especially important for service in-

dustries which operate in virtual spaces. (Jones et al.,

2000) developed trust requirements for e-business on

the foundation of the parameters of trust and de-

pendability. Fulfilling these requirements leads to

customer satisfaction and hence to customer loyalty

which is the foundation of every customer relation-

ship (Chaffey, 2009). Moreover most Frameworks

involve a product related block into their constructs

(Osterwalder et al., 2005). This element refers to the

overall value proposition offered by a company to-

wards their customers.

In fact there are manifold additional elements of

business model frameworks stated in the current liter-

ature, which have not crucial importance for this set-

ting. Against the special backgroundof providing het-

BusinessModelFrameworktoProvideHeterogeneousMobilityServicesonVirtualMarkets

147

erogeneous mobility modes on a centralized virtual

marketplace, it can be concluded that existing frame-

works doesn’t fit exactly to these conditions. This im-

plies the need to develop a new framework especially

for this context.

3 HETEROGENEOUS MOBILITY

MODE INTEGRATION BASED

ON INCENTIVE ORIENTED

BUSINESS MODELING

Information technology offers extensive strategic and

economic possibilities. It is creating new opportuni-

ties for margin enhancement, increased customer sat-

isfaction, capital efficiency, and agile organizational

behavior (Kagermann et al., 2010). Decision makers

have to consider new technological solutions that re-

shape existing business models (Teece, 2010). Partic-

ularly, the integration of diverging mobility modes via

information systems reshapes existing business mod-

els. The following part explains the shifts in compa-

nies business models and refers to related consolida-

tion projects.

3.1 Involvement

Actors can provide their mobility services on a cen-

tralized platform with different degree of involve-

ment. (Buchinger et al., 2013a) distinguished be-

tween an “independent partner scenario”, “interven-

ing partner scenario” and an “open service platform

scenario”. The degree of involvement influences all

constitutive business model pillars in major part.

3.2 Activity Configuration

Activities to provide products or services are a major

part of business model concepts. In this context, the

IB influences activities, that are logistically essential

for delivering services to the customer in major part.

(Buchinger et al., 2013a) showed the influence of an

open software system scenario on infrastructure of ve-

hicle sharing providers activities. They distinguished

between service and infrastructure providers and in-

cluded a data layer. More precisely, they showed that

activities like user registration, reservation, billing,

clearing and authentication can be outsourced to an

information system. This system basically aggregates

the data.

3.3 Distribution Model

The product related aspects are a central part of busi-

ness models (Osterwalder et al., 2002) (Osterwalder

et al., 2005). This pillar is closely connected to this

topic, but the exact meaning is different. The distri-

bution model is the way, how mobility services can

be purchased by the customer on the information sys-

tem. The distribution method can be designed in sev-

eral ways: For example, the European project SU-

PERHUB

8

develops an open source platform to com-

bine heterogeneous mobility offers altogether in real

time. Additionally, the offering is going to be pro-

vided on an mobile app. SUPERHUB enables cus-

tomized multimodal routing and presents the com-

bined offering within a flexible best price solution.

In contrast to this, Seatz

9

travel network assistant of-

fers a distinction between the greenest, cheapest and

fastest traveling alternative. Moreover an IB offers

new possibilities for cooperation. The construct is in-

spired by contracts in the telecommunication sector:

based on frame contracts between participating mo-

bility providers, the system enables the offering of

combined multimodal ticket products. These prod-

uct bundles support the intention of integrating dif-

ferent mobility modes and set strong incentives to-

wards customers to get in touch with alternative mode

options. Because of the significant heterogeneity of

modes, it is difficult to establish a non restrictive “flat

rate model” for all modes. Therefore, a new portfolio

of products bundles has to be designed. The basis for

all product bundles form subscription contracts for the

usage of public transport modes. In addition this basis

has to be extended through subscriptions of commer-

cial vehicle sharing. In fact this creates a new ticket,

which sets incentives for intermodal travel behavior.

However, the integrationof modes like car pooling

into this concept is challenging. These modes usually

are paid by cash money. This circumstance requires a

solution based on information technology, which fa-

cilitates a centralized organization and enables the in-

tegration of car pooling - a virtual currency based pay-

ment mechanism.

3.4 Virtual Payment Mechanism

Virtual currencies originally are designed as loyalty

programs to bound customers to in-house services.

A modified strategy is the cooperation scheme, also

defined as coalition loyalty or cross loyalty, which

describes the facilitation of loyalty cards at multi-

ple, possibly competing, retailers (Buchinger et al.,

8

http://www.superhub-project.eu

9

http://http://www.seatznetwork.com/home/

ICE-B2014-InternationalConferenceone-Business

148

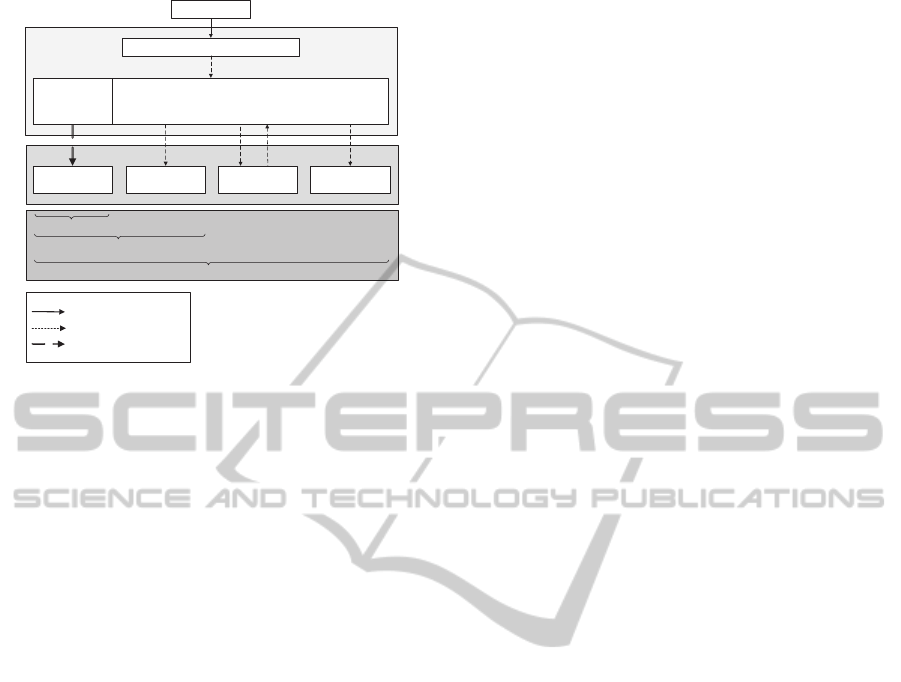

Public

transportation

Mobility

Modes

Virtual Currency Mangement

Customer

Car Sharing Car Pooling

Additional

services

Flexible Component

Product A

Product B

Product C

Product

Content

Virtual Currency

Mechanism

Virtual Currency flow

Cash flow

Legend

Subscription

Subscription

Component

Digital Wallet

Figure 2: Information Broker Business Model Pillar Con-

nection.

2013a). There are preceding considerations of im-

plementing a virtual payment mechanism as a part

of business models for this context (Buchinger et al.,

2013b). In contrast to these intentions of virtual cur-

rency mechanisms, it has the function to virtualize

the payment process of car pooling and integrate the

mode into the system. To foster the usage of car pool-

ing, this virtual currency mechanism has to be con-

structed with consideration of user preferences and

product conditions (Beutel and Krempels, 2014). It

allows to earn virtual currency amounts by provid-

ing vehicle sharing capacity and spend it towards

other transport modes under consideration of ticket

product portfolio characteristics and customer prefer-

ences. Hence, the virtual currency mechanism con-

centrates all mobility related transactions onto the in-

formation broker. This projects the fundamental idea

of coalition loyalty towards the collaborating mobility

provider base and creates additional value for the cus-

tomers. As described before, the establishment of a

virtual currency based payment mechanism is essen-

tial to integrate mobility modes like car pooling. The

cash payment of car pooling can be replaced by a vir-

tual currency payment to integrate the related trans-

actions into the IB system. Moreover, this payment

mechanism allows to extend the collaborative prod-

uct portfolio due to car pooling services. The “flat

rate” products can now be extended through quantita-

tively limited virtual currency amounts. 2 illustrates

the mechanism and possible product variations. Prod-

uct C is supposed to have the highest mode integration

as well as strongest incentive effect for mode switch-

ing. Crucially important for the mechanism design

is the implementation of a central wallet, which al-

lows to execute offline authentications with car pool-

ing users (Beutel and Krempels, 2014).

3.5 Financial Model

Applying an adequate and effective financial model,

consisting of a revenue model and a cost model, re-

sults in a sustainable flow of revenue, which guar-

antees the future engagement in all above described

activities. The revenue model describes the various

ways the company generates cash flow by “translating

the value it [the organization] offers to its customers

into money” (Dubosson-Torbayet al., 2002). The cost

structure refers to the sum of all resulting cost needed

to perform the activities required to create and deliver

the value proposition to the target customer (Oster-

walder et al., 2005). (Silver, 2007) refers to them as

the “capital requirements” needed to execute the busi-

ness model.

4 CONCLUSION

We contributed a business model framework for pro-

viding heterogeneous mobility services on an open

virtual marketplace, see 3. Business model frame-

works can be used for analyzing, understanding, shar-

ing, managing and patenting of business models (Os-

terwalder et al., 2005). In addition, its importance is

growing in a cooperativescenario of platform consoli-

dation: Insecurity, new environmental challenges and

transparent market conditions require a guide lining

framework for orientation.

Fundamentally, all components of the business

models are going to be determined by the degree of

involvement into the Information Broker system. The

main pillars are activity configuration, distribution

model, virtual payment mechanism and the financial

model. These pillars in turn, can be individually spec-

ified in more detail, as described before.

It is crucially important for business model design,

to consider the mutual interdependencies of the com-

ponents. For example, virtual payment design influ-

ences the distribution model, as well as the activity

configuration.

Future Work

Constitutive on this framework, concrete business

models have to be developed in the future, to enable

an efficient providing of heterogeneous mobility ser-

vices on a centralized software system. During this

work, it is possible to expand the framework due to

new insights. Moreover, it would be interesting to

BusinessModelFrameworktoProvideHeterogeneousMobilityServicesonVirtualMarkets

149

Involvement

Activity

Configuration

Distribution

Model

Virtual Payment

Mechanism

Financial Model

Business Model

Cost Structure

Revenue

Streams

Loyalty

Concept

Mode

Integration

Incentive

Regulation

Value Chain Best Price

Preference

Orientation

Multimodal

Tickets

Figure 3: Business Model Framework.

quantify the financial outcomes of the construct and

calibrate the business model accordingly.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was founded by German Federal Ministry

of Economics and Technology for project Mobility

Broker (01ME12135A).

REFERENCES

Afuah, A. and Tucci, C. (2000). Internet Business Models

and Strategies Text and Cases. Irwin/McGraw-Hill,

New York.

Ahuja, G. (2000). Collaboration Networks, Structural

Holes, and Innovation: A longitudinal study. Admin-

istrative Science Quarterly, 45(3):425–455.

Basole, R. C. and Rouse, W. B. (2008). Complexity of ser-

vice value networks: Conceptualization and empirical

investigation. IBM Syst. J., 47(1):53–70.

Bentenrieder, M. . (2010). Mein Haus, mein Pool, meine

Mobilit¨at [My House, My Pool, My Mobility]. Auto-

motive Agenda, 3(4):S.34–43.

Beutel, M. C. and Krempels, K.-H. (2014). Encompass-

ing Payment for Heterogeneous Travelling - Design

Implications for a Virtual Currency based Payment

Mechanism for Intermodal Public Transport. In Pro-

ceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Smart

Grids and Green IT Systems (SMARTGREENS 2014),

Barcelona, Spain.

Buchinger, U., Lindmark, S., and Braet, O. (2013a). Busi-

ness Model Scenarios for an Open Service Platform

for Multi-Modal Electric Vehicle Sharing. In SMART

2013 : The Second International Conference on

Smart Systems, Devices and Technologies, pages 7–

14, Roma, Italy.

Buchinger, U., Ranaivoson, H., and Ballon, P. (2013b). Vir-

tual Currency for Online Platforms - Business Model

Implications. In Proceedings of the 10th International

Conference on e-Business (ICE-B 2013), pages 196–

206, Reykjavik, Iceland.

Chaffey, D. (2009). E-Business and E-Commerce Manage-

ment. FT/Prentice Hall, Harlow, England., fourth edi-

tion.

Doz, Y. L. and Hamel, G. (1998). Alliance advantage: The

art of creating value through partnering. Press, Har-

vard Business School, Boston.

Dubosson-Torbay, M., Osterwalder, A., and Pigneur, Y.

(2002). E-business model design, classification, and

measurements. Thunderbird International Business

Review, 44(1):5–23.

Easton, G. (1992). Industrial Networks: A Review. In Axels-

son & G. Easton (Eds.), Industrial Networks: A New

View of Reality. B., Routledge, London.

Faber, E., Ballon, P., Bouwman, H., Haaker, T., Rietkerk,

O., and Steen, M. (2003). Designing business models

for mobile ICT services. In Proceedings of the 16th

Bled Electronic Commerce Conference, Bled, Slove-

nia.

Gomes-Casseres, B. (1994). Group versus group: How al-

liance networks compete. Harvard Business Review,

72(4):62–74.

Gulati, R., Nohria, N., and Zaheer, A. (2000). Strategic

networks. Strategic Management Journal, 21(3):203–

215.

H˚a kansson, H., Ford, D., Gadde, L.-G., Snehota, I., and

Waluszewski, A. (2009). Business in networks. John

Wiley & Sons, London.

Johnson, M. W., Christensen, C. M., and Kagermann, H.

(2008). Reinventing your business model. Harvard

business review, 86:12.

Jones, S., Wilikens, M., Morris, P., and Masera, M. (2000).

Trust Requirements in e-Business. Communication

ACM, 43(12):81–87.

Kagermann, H., Osterle, H., and Jordan, J. M. (2010). IT-

Driven Business Models. John Wiley & Sons, 1. edi-

tion.

ICE-B2014-InternationalConferenceone-Business

150

Oliver, C. (1990). Determinants of Interorganizational

Relationships: Integration and future directions.

Academy of Management Review, 15(2):241–265.

Osterwalder, A., Hec, E., Lausanne, U. D., and Pigneur, Y.

(2002). An e-Business Model Ontology for Modeling

e-Business. BLED 2002 Proceedings.

Osterwalder, A., Pigneur, Y., and Tucci, C. L. (2005). Clar-

ifying Business Models: Origins, Present, and Future

of the Concept. Communications of the Association

for Information Systems, 16:1–25.

Peppard, J. and Rylander, A. (2006). From Value Chain to

Value Network: Insights for mobile operators. Euro-

pean Management Journal, 24(2-3):128–141.

Pfeffer, J. and Nowak, P. (1976). Joint Ventures and Interor-

ganizational Interdependence. Administrative Science

Quarterly, 21(3):398–418.

Podolny, J. (1998). Network Forms of Organization. Annual

Review of Sociology, 24:57–76.

Porter, M. and Millar, V. (1985). How information gives you

a competitive advantage. Harvard Business Review,

63(4):149–160.

Porter, M. E. (1985). Competitive Advantage: Creating

and Sustaining Superior Performance. The Free Press,

New York.

Rayport, J. and Sviokla, J. (1995). Exploiting the virtual

value chain. Harvard Business Review, 73(6):75–85.

Silver, D. (2007). Smart Start-Ups: How to Make a For-

tune from Starting Online Communication. Piatkus,

London.

Stabell, C. and Fjeldstad, O. (1998). Configuring value

for competitive advantage: On chains, shops and net-

works. Strategic Management Journal, 19:413–437.

Teece, D. J. (2010). Business Models, Business Strategy

and Innovation. Long Range Planning, 43(2-3):172–

194.

Timmers, P. (1998). Business models for electronic mar-

kets. Electronic Markets, 8:3–8.

Vanhaverbeke, W. and Cloodt, M. (2006). Open innovation

in value networks. In Chesbrough, W., Vanhaverbeke,

W., and West, J., editors, Open innovation: Research-

ing a new paradigm, pages 258–281.

Veit, D., Clemons, E., Benlian, A., Buxmann, P., Hess, T.,

Kundisch, D., Leimeister, J. M., Loos, P., and Spann,

M. (2014). Business Models. Business & Information

Systems Engineering, 6(1):45–53.

BusinessModelFrameworktoProvideHeterogeneousMobilityServicesonVirtualMarkets

151