A Computer-based Educational Adventure Challenging Children

to Interact with the Natural Environment Through Physical

Exploration and Experimentation

Uwe Terton and Ian White

Engage Research Lab, University of the Sunshine Coast, Maroochydore, Australia

Keywords: ADHD, Australia, Autism, Biodiversity, Biotope, Computer based Learning, Computer in Education, e-

Learning, Environmental Learning, Environmental Education, Game based Learning, Game Design, ICT,

Internet, Interface Design, Motor Activity, Mobile Computing in Education, Outdoor Education, Primary

School Education, Queensland, Situated Learning, Video Games, Young People and the Environment.

Abstract: The researchers’ paper discusses the development of a computer-based educational game which challenges

children to interact with the natural environment through physical exploration and experimentation. The

researchers’ project seeks to counteract the negative behaviours associated with excessive computer game

play amongst children 8 to 12 years old. By leveraging the positive learning outcomes that can be achieved

through computer gaming and combining these with outdoor learning strategies, Jumping the Fence

encourages children to take responsibility for surveying and caring for a local ecosystem. The game requires

children to reflect critically on their computer use, become more physically active, gain social skills and

develop an affinity towards nature. Educators are able to adapt the game to their school's own curriculum

and thereby provide an alternative learning strategy that encourages physical and social engagement.

1 INTRODUCTION

The potential benefits of computer games in

education, training and entertainment are widely

appreciated, but their downside is also equally a

matter of concern. Whilst computer games are

mostly played for recreational purposes, or to keep

the player in suspense, the frequency of game

playing and the average duration of the games we

now engage in often bring about unintended

consequences. On the other hand, not everything

about playing computer games is bad. Computer

Based Learning (CBL) has great promise as an

instructional tool and, whether we like it or not,

proficiency with computers has become a key part of

the skill set required by modern children, and

familiarity with interactive technologies is essential

for success in contemporary society.

The question that concerned the researchers was:

how can we balance the benefits of CBL and

computer literacy with the disadvantages of

spending large amounts of time in front of a

computer? Would it be possible to design a

computer based learning game that actually required

students to get up from their seats and move around

in their nearby environment in order to engage with

and advance in the game? In order to answer to these

questions, the idea of creating an educational game

called Jumping the Fence (JTF) was born. The game

has been proven to be successful in

providing

alternative learning strategies that encouraged

students in physical and social engagement.

The paper covers the methodology, the design

and construction of the game, the observations made

during the testing phases and end with a discussion

on the outcomes of the research project and by

finally providing some suggestions for future

research.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

The literature review revealed quite early in the

study that computer based simulations mirroring real

life examples combined with a good narrative are

known to be highly effective in developing an

understanding of complex systems (Wastiau,

Kearney and Van den Berghe, 2010; Barab, 2009;

93

Terton U. and White I..

A Computer-based Educational Adventure Challenging Children to Interact with the Natural Environment Through Physical Exploration and Experimen-

tation.

DOI: 10.5220/0004954300930098

In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU-2014), pages 93-98

ISBN: 978-989-758-022-2

Copyright

c

2014 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

De Freitas and Neumann, 2009; Royle, 2009; Salen

and Zimmerman, 2004; Dziorny, 2003; Garris, 2002;

Klaila, 2001; Prensky, 2001). It also became clear

that such strategies could be readily applied to

developing real time educationally focused games

that address complex environmental and scientific

issues and that outdoor learning was a tried and

tested educational strategy well suited to support this

area of learning (Young et al., 2012; Knoll, 2011;

Nichol et al., 2007; Cooper, 2006; Dillon et al.,

2005; Leger, 2003; Lund, 2002; Neill, 2002;

Fjortoft, 2000; Lappin, 2000; Moore and Wong,

1997). For these reasons, the study was designed to

find out whether or not the idea behind the Jumping

the Fence educational game would work in practice

and whether the gaming and learning strategies

developed might be refined for further use in other

areas of education. Furthermore, it became apparent

that if such an idea was successful, such a game

might encourage users to reflect critically on their

daily computer use and provide educators with a

healthy educational alternative to the current

classroom based approach to computer based

learning activities. The questions arising from the

literature review resulted in the formulation of the

following two guiding questions:

Can a computer based educational game be

developed that encourages young people to

physically interact with the natural environment?

What interpersonal strategies might be identified

that would help achieve these outcomes?

3 METHODOLOGY

The Jumping the Fence project utilises design-based

research as its primary methodology, since this

approach allows for the carrying out of both design

and testing in the context of real-life settings (Barab

et. al 2005 p.91). Although normally considered to

be a methodology primarily associated with

educational practice, the iterative nature of design-

based educational research aligns directly with the

working methods used extensively in both creative

arts practice and throughout the design professions.

The use of an educational, design-based research

methodology allowed the author to create an initial

application which could then be used as a test

vehicle, from which outcomes could be used to

improve the application in an iterative process—as is

typically done in most design related research.

According to Barab and Squire (2004) “design-

based research involves introducing innovations into

the booming, buzzing confusion of real-world

practice (as opposed to constrained laboratory

contexts) and examining the impact of those designs

on the learning process” (Barab and Squire 2004

p.4). From such testing the “lessons learned are then

cycled back into the next iteration of the design

innovation” (Barab, 2005 p.92). This iterative

approach to design allows for unexpected or

unpredicted events and outcomes identified during

test trials to be accommodated into the design

process and future outcomes. In this way, the

researchers could be open minded to surprises and

react appropriately by adjusting the design of the

application to cater for the needs of the research

subjects and the environment where the test takes

place. To gain a better understanding of how

teachers and students were responding to the design

and functioning of the game, the researcher relied

primarily on the gathering and analysis of both

quantitative and qualitative data, which in turn

determined the evolving technical structure of the

game mechanics and game story. Throughout the

testing of the game, student and teacher interaction

with the game, as well as the learning outcomes

were measured by practically assessing the student’s

acquired knowledge, reactions and experiences in

four ways—via oral assessment (interviews with

students and staff before and after playing the

game); by questionnaires at set intervals during the

study; by confidential feedback from teachers based

on course assessment and subsequent classroom

observations and, lastly, by observation in the field

(video recording how students and teachers acted

and interacted and documenting a range of

associated activities, such as what students observed

and wrote about in their field diaries). In particular,

teacher and student feedback and interviews later

proved to be a valuable source of evidence that

clarified many of the activities and interactions that

were evident in videotaped field recordings.

4 THE GAME

The aim was the design and production of an

alternative form of computer game, which seeks to

blend the benefits of computer based educational

gaming with a range of strategies that encourage the

gamer (and student) to move beyond the restrictions

of the computer and the classroom and engage

directly with the natural environment—in the

process forming research groups, developing social

skills and taking part in a range of low-impact,

outdoor physical activities. In the playing of the

game, it is hoped that the student gamers will learn

CSEDU2014-6thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

94

about Australian native wildlife, science, the

environment and sustainability issues and—above

all— they might have fun in the process. The

practical development of the first trial version of the

Jumping the Fence game was based on a preliminary

study designed to identify a suitable area of study to

which the researcher’s project and ideas could be

applied and tested. It was decided to structure the

game and its educational outcomes, its visual design

and language, as well as the levels of computer

literacy required to play it so as to be relevant to

Australian Year 5–7 students engaged in the

standard Queensland primary school curriculum.

The children in the sample that volunteered to

participate in the study were typically between 9 and

12 years of age and were drawn from two composite

year classes (grades 5-6 and grades 6-7)—which

accounts for the wider than might be expected age

range for such a trial. Since the primary aim of the

JTF game was to encourage students to engage with

outdoor learning and physical activities and, in the

process develop an understanding of environmental

and sustainability issues, as well as knowledge of

Australian wildlife, plants and habitat were

identified as being most relevant to the author’s

project. When students were asked about their

favourite non computer games, the following topped

the list: Lego, swimming, dancing, camping, bike

riding, cops and robbers (and other chasing games),

supervised team sports activities and some board

games, in particular Dungeons and Dragons and

War Hammer. Most students were familiar with

Chess and some had seen Backgammon, but these

were more often played by parents or older relatives.

That so many children were familiar with Dungeons

and Dragons and the concept of role playing games

(possibly because the game would have been played

by their parents as teenagers and then by them with

their children) suggested to the authors that adapting

the principles of role playing games might not be as

problematical as first thought. Since these games are

typically overseen by a Game Master, who controls

and delivers the story, the role of the teacher—as

guide, administrator, content developer and

arbitrator— could also be easily accommodated. In

the same way that these games break up their world

into a series of grids and tiles, breaking up the JTF

game in small sections which interact to form a

larger picture therefore became an obvious design

and playing strategy. Requiring students to

accurately measure and survey their outdoor

“research” area and turn it into a 2 by 2 meter grid

encompassing an area 8 metres by 6 metres then

map this area into the computer—along with making

a detailed analysis of the plants and animals that live

in each square, requires students to apply skills in

maths, geometry, drawing, writing and teamwork as

well as observational and communication skills.

Children must think spatially and learn how to turn

their complex three dimensional real world area into

a simple two dimensional map that uses colours and

legends for representation. At the same time the

players are creating the very grid on which the game

will be constructed and subsequently played.

The narrative was created to encapsulate as many

of the ELs outcomes for the Year 5 and Year 7 Key

Learning Areas (SOSE, Science and Health and

Physical Education) as possible, with the view to

adding and refining them as the project moved

forward. The protagonist of the game is a young

female kangaroo who goes by the name of Kangi.

Kangi is a very up to date kangaroo who spends a lot

of her time in the wilderness of Australia, but who

often comes into cities and towns to study humans

and learn their ways. Kangi has many magical

qualities, including the ability to speak to children

and use a variety of modern communications tools

(without having to pay for them!). Her mission is to

explain to students just how vulnerable the

Australian natural environment is and help them

understand how they can help protect it and her

friends (Figure 1). Importantly, Kangi needs the

children’s help to not only save the local plants and

animals, but to provide information for her friends

back home, who are missing their relatives and

friends.

Figure 1: Kangi and her friends explaining how an eco

system works.

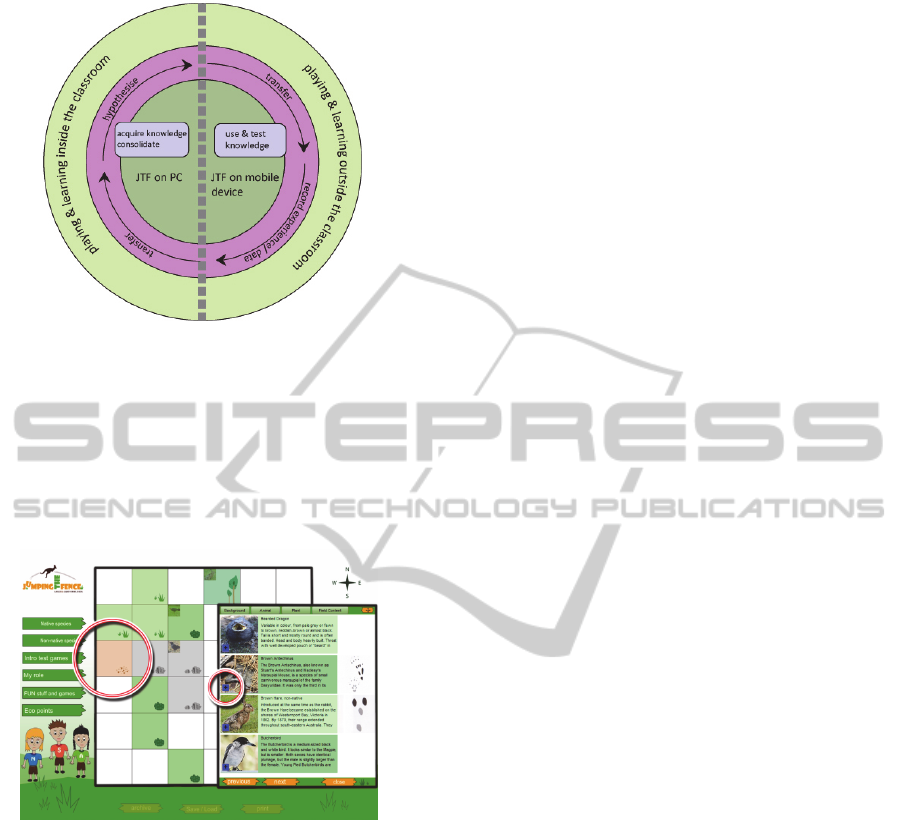

In summary JTF’s model of teaching and learning is

a semi-closed circuit model (Figure 2), where the

research and learning starts in class by playing the

introductory levels of the game on the school

workstations. Students can work individually or in

their teams at the initial stage, but as students are

assigned their roles, each student moves to their own

AComputer-basedEducationalAdventureChallengingChildrentoInteractwiththeNaturalEnvironmentThrough

PhysicalExplorationandExperimentation

95

Figure 2: Semi-closed circuit model

(indoors>outdoors>indoors...).

computer the focus on the learning tasks associated

with their task in the game. Each indoor and outdoor

task is assigned by the game master or game system,

but input from external sources (student research,

new knowledge from guest speakers, the internat.)

can also be entered into the system (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Students placing content into the computer based

game interface.

5 TESTING

The testing and development of JTF was done with

the co-operation of the teachers and students of

Sunshine Beach Primary School, on the Sunshine

Coast in South East Queensland between October

2008 and July 2010. The first study group consisted

of 12 primary school students aged between 8 and

10 years old and the second study group consisted of

25 primary school students of the same age group.

Students in both group were identified by the

teachers as suffering from Attention Deficit

Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) but were not

identified individually. The first study was divided

into two parts. In the first visit, the students were

asked to fill in a questionnaire that helped the

researchers to build a profile of the students so that

the researchers could develop and customise the

initial game concept on the basis of the student’s

preferences and the identified requirements of the

teachers and the curriculum. The second part of the

study allowed the researcher to test the initial game

prototype with the students, gain feedback and make

appropriate improvements. The outcomes of the

trials were interpreted and discussed with the

students and teachers and these revised findings

informed subsequent changes to the game prototype.

The findings and observations made during this

stage of the study are discussed in the first part of

this chapter. The purpose of the second study was to

test and refine the computer based prototype within

the school setting. As before, after each trial the

students were asked to fill in a feedback

questionnaire and the results were discussed with the

students and teachers and then used to further

improve the prototype. The findings and

observations from both sets of studies were then

used to ascertain to what extent the game fulfilled

the researchers’ initial proposals and research topic.

5.1 Findings of the Game Trials

The results of both test trials suggested that the idea

behind the Jumping the Fence game is valid and that

it is possible to design a computer based learning

game that requires students to leave the classroom

and spend more time outdoors engaging with the

natural environment. It is also relatively easy to

encourage students / players to take on the role of

active researchers rather than passive observers,

given that many are already familiar with role

playing games based on their existing experiences of

computer games. In taking on their roles, the

students clearly developed an understanding of what

a biotype is (even though very few of them were

aware of most of the correct terminologies) and, in

so doing, most developed a sense of responsibility

for, and personal connection with, their research

areas. Overall, students indicated there was a high

level of pleasure associated with playing JTF-both

parts-the computer based indoor activities and

outdoor based non-computer based activities). To

the authors, perhaps the two things that came across

most strongly from both groups were the enjoyment

and pleasure of being outside away from the

constraints of the classroom, and the sense of

attachment the students clearly developed for the

area used in the study. Giving students custodianship

CSEDU2014-6thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

96

and a duty of care for their study area is an important

part of the JTF game strategy, as it requires the

application of physical effort as well as the

utilisation of appropriate knowledge. Many children

by this age have already developed an appreciation

for nature and it is therefore relatively easy to

encourage most children to become involved in JTFs

activities. However, an unexpected outcome of the

second study was the number of students (8/24) who

specifically identified themselves as not liking being

outdoors or who found the experience stressful.

Responses such as “I like to stay inside’” “Because

outside is nil,” “It is no fun being outside” and

“Because I get headaches outside,” were quite

unexpected. Although it is perfectly normal for some

children to prefer being indoors, it seems that having

one third of the students so actively not liking being

outdoors is either an aberration or is an indication

that changing trends in society may be influencing

this outcome. There is a lot of anecdotal evidence

suggesting that contemporary children are leading

much more protected lives than in the past and those

current concerns over “stranger danger” and health

and safety issues are bringing about a culture in

which children are over protected both at home and

at school. It would certainly be unfortunate if this is

indeed indicative of a long term trend, although it

would be interesting to see whether playing JTF

over a longer period might change the attitude of

some of these students to being outdoors. The

students were also very concerned that their biotope

would not survive after they left the school (in

follow up discussions it seemed to be understood

that they would continue to care for the area in their

own time after the project was finished) unless

arrangements were made to have other students look

after it in the future. Several students proposed that

responsibility should be passed on to younger

students and one student argued that it needed to be

someone who could be trusted in the long term, a

statement which demonstrates not only how closely

the students had become attached to their study area,

but an awareness of the longer term needs of the

environment they had nurtured. At the 2010 trial, the

majority of students thought that it would be

advantageous to use mobile devices such as smart

phones and tablet computers to play JTF and that a

mobile device would enhance the game by providing

instant access information in the field. Several

students suggested that the entire game should be

ported to a mobile format for this reason (and also

because it meant spending more time outdoors). The

students noted that it would be easier to get

information directly from the Internet in the course

of the game play; but many students argued that

mobile devices would not only speed up the game

play, they would enable them to stay outdoors all the

time. It was quite clear from both written student

feedback and follow up discussions that being

outdoors and away from the classroom was a major

attraction of playing JTF. In both field observations

and follow up discussions with the teachers it was

noted that after only a short time outdoors, the

classes were significantly calmer and quieter than

they were observed to be when working in the

classroom. One teacher later suggested that by the

end of the trial it was as if he had different students

in the class, since the group as a whole was

generally much more collected and better

disciplined—in particular the ADHD students, for

whom the physical demands of the game proved

especially beneficial.

6 LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE

RESEARCH

The data and findings described derive from only

two small-scale studies, with samples consisting

both times of the equivalent of just one class

(although students in the first trial were from

different class groups and largely did not know each

other, as opposed to the second trial where all

students were classmates). Nevertheless, the limited

number of students will have influenced the validity

of the study results to some degree. For this reason,

it is suggested that further studies be undertaken

with larger sample groups. The benefits associated

with outdoor education are well documented in the

literature, but observing how JTF works in a more

urbanised environment would certainly be of great

value if the game is to be thoroughly tested for its

potential as a vehicle for environmental education.

7 CONCLUSIONS

The findings clearly demonstrate that the JTF game

supports teaching and learning in both the indoor

(mainly computer activity based) and outdoor

learning environment. The game also shows that

individual and group tasks can be designed that

bring team members together to engage in co-

operative learning.

AComputer-basedEducationalAdventureChallengingChildrentoInteractwiththeNaturalEnvironmentThrough

PhysicalExplorationandExperimentation

97

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank all of the staff and students

from the Sunshine Coast State Primary School, who

helped us in conducting the two studies in 2008 and

2010.

REFERENCES

Barab, S. A., Arici, A. and Jackson, C., 2005. Eat Your

Vegetables and Do Your Homework: A design Based

Investigation of Enjoyment and Meaning in Learning.

In: Educational Technology. 45 (1), pp.15-21.

Barab, S.A. and Squire, K., 2004. Design-Based Research:

Putting a Stake in the Ground. In: THE JOURNAL OF

Learning Sciences. 13(1), pp.1–14.

Barab, S. A., Gresalfi, M. and Arici, A., 2009. Why

Educators Should Care About In Virtual Games:

students act as investigative reporters, environmental

scientists, and historians who resolve meaningful

dilemmas. In: Educational Leadership. 67 (1), pp.76-

80.

Cooper, G., 2006. Outdoor Education & Field Studies:

Disconnected Children, Learning spaces framework:

learning in an online world. In: HORIZONS. 33,

pp.22-25.

De Freitas, S. and Neumann, T., 2009. The use of

exploratory learning for supporting immersive

learning in virtual environments. In: COMPUTERS &

LEARNING. 52(2), pp.343-352.

Dillon, J., Rickinson, M., Teamy, K., Morris, M., Choi, M.

Y., Sanders, D. and Benefield, P., 2005. The value of

outdoor learning: evidence from research in the UK

and elsewhere. In: SCHOOL SCIENCE REVIEW. 87

(320). pp. 107-111.

Dziorny, M., 2003. Is Digital Game-based Learning

(DGL) Situated Learning. Master thesis, University of

North Texas, USA (online). (Accessed 10 February

2011). Available from: http://www.marydziorny.com/

DGL_and_Situated_Learning_paper.doc.

Fjorthoft, I. and Sageie, J., 2000. The Natural

Environment as a Playground for Children: Landscape

Description and Analysis of a Natural Landscape. In:

Landscape and Urban Planning. 48(1/2), pp.83-97.

Klaila, D., 2001. Game-Based E-Learning Gets Real,

Want to unlock the mystery of effective e-learning?

Think design. And fun! (online). (Accessed 28 March

2010). Available from: http:// www.astd.org/LC/2001/

0101_klaila.htm.

Knoll, M., 2011. Schulreform Through “Experiential

Therapy” Kurt Hahn – An Effiacious Educator.

Catholic University Eichstaett Germany (online).

(Accessed 08 January 2012). Available from:

http://www.jugendprogramm.de/bibliothek/literature/k

urt-hahn/ ED515256.pdf.

Lappin, E., 2000. Outdoor Education for Behavior

Disordered Students (online). (Accessed 03 October

2009). Available from: http://www.kidsource.com/

kidsource/content2/outdoor. education.ld.k12.3.html.

Lund, M., 2002. Adventure Education (online). (Accessed

17 January 2012) .Available from:

http://australie.uco.fr/~cbourles/option/Theorie/Hahn/

Adventure%20Education.htm.

Moore, R. and Wong, H., 1997. Natural Learning:

Rediscovering Nature’s Way of Teaching. Berkeley,

CA MIG Communications.

Neill, J.T., 2002. What is Outdoor Education? Definition

(Definitions) (online). (Accessed 04 May 2010).

Available from: http://www.wilderdom.com/

definitions/definitions.html.

Nichol, R., Higgins, P., Ross, H., and Mannion, G., 2007.

Outdoor Education in Scotland: A Summary of

Research (online). Scottish Natural Heritage.

Edinburgh. Available from: http://www.snh.org.uk/

pubs/detail.asp?id=852.

Prensky, M., 2001. Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants.

In: On the Horizon (online). 9 (5), (Accessed 15

August 2009), Available from:

http://www.marcprensky.com/writing/Prensky% 20-

%20Digital%20Natives,%20Digital%20Immigrants%

20-%20Part1.pdf.

Royle, K., 2009. Computer games and realising their

learning potential. Game Based Learning. Video

Games, Social Media & Learning (online). (Accessed

02 November 2010). Available from:

http://innovateonline.info/index.php?view=article&id=

433&action=login.

Salen, K. and Zimmerman, E., 2004. Rules of play.

Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA: MIT PRESS.

St Leger, L., 2003. Health and Nature - New Challenges

for Health Promotion. In: Health promotion

International. 18 (3), pp.173–175.

Wastiau, P., Kearny, C. and Van Den Berghe, W., 2010.

Games in school: How are digital games used in

schools? In: European Schoolnet, EUN Partnership

AISBL, Brussels, Belgium.

Young M. F. et al., 2012. Our Princess is in Another

Castle: A Review of Trends in Serious Gaming for

Education. In: Review of Educational research 82(1),

pp. 61-89.

CSEDU2014-6thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

98