Teaching the Arabic Alphabet to Kindergarteners

Writing Activities on Paper and Surface Computers

Pantelis M. Papadopoulos

1

, Zeinab Ibrahim

1

and Andreas Karatsolis

2

1

Carnegie Mellon University in Qatar, Doha, Qatar

2

Massachussetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, U.S.A.

Keywords: Early Childhood Education, Writing, Arabic Language Learning, Tabletop Surface Computers.

Abstract: This paper presents initial results regarding writing activities in the context of the ALADDIN project. The

goal of the project is to teach Modern Standard Arabic in 5-year-old kindergarten students in Qatar. A total

of 18 students, enrolled in the ‘Arabic Class’, participated for 9 weeks in the activities of the project. All

students were native speakers of the Qatari dialect. Learning activities involved both typical instructional

methods, and the use of specifically designed tools for tabletop surface computers. The paper focuses on

writing activities and on how the affordances of surface computers affected students’ performance and

attitude towards the Arabic class and, consequently, the Arabic language.

1 INTRODUCTION

The general scope of our work in the 3-year long

ALADDIN (Arabic LAnguage learning through

Doing, Discovering, Inquiring, and iNteracting)

project is to teach Qatari students in kindergarten

Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) and help them

understand the connection between MSA and the

dialect. This research draws extensively upon the

works of Ibrahim (2000, 2008a, 2008b, 2009)

pertaining to Arabs language attitudes, the

relatedness of the MSA to the dialect and the native

speakers awareness, lexical separation as a

consequence of diglossia, the use of technologies in

Arabic language learning, and language planning

and education.

At the age of 5, native speakers in Qatar follow a

rather scholastic instructional method, based mostly

on Behaviorism, following trial-and-error and

mnemonic tasks. At the same time, children are

exposed to both the MSA through the Media and to

the Qatari dialect spoken at home and in everyday

life. Unfortunately, very little research, if any, has

reported on the state of the Arab children’s

vocabulary at the age of five when they start

schooling. Saiegh has done few, but very crucial,

studies on the effect of diglossia on children’s’

learning (2003, 2004, 2005, 2007). The “scholastic

way,” which does not go well with new innovative

technologies and methods of teaching, actually

makes the students feel far from their actual

surroundings.

In this context, the ALADDIN project aims to

teach students, by introducing a new comprehensive

curriculum based on a communicative approach

utilizing listening sessions, narratives, discussion,

educational games, and new technologies (i.e.,

tabletop surface computers) (see Papadopoulos et

al., 2013, for more information).

The learning goals for the kindergartner students

are to (a) recognize, and (b) produce the letters of

the Arabic alphabet. Recognition refers to visual and

audio recognition of a letter, while production refers

to students’ ability to write the letters. The research

questions addressed in the paper focus on the latter,

analyzing (a) how the affordances of tabletop

surface computers alter the learning experience, and

(b) the impact of this new technology to students’

performance and behavior.

2 BACKGROUND

2.1 The Arabic Language

Arabic is a diglossic language, it has a high form

used in all formal contexts (MSA), and a low form

used in all daily contexts (Ferguson, 1991). It

consists of 28 consonants, 3 long vowels, and 3 short

vowels. Short vowels are not written within the

433

M. Papadopoulos P., Ibrahim Z. and Karatsolis A..

Teaching the Arabic Alphabet to Kindergarteners - Writing Activities on Paper and Surface Computers.

DOI: 10.5220/0004942204330439

In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU-2014), pages 433-439

ISBN: 978-989-758-020-8

Copyright

c

2014 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

word, but either above or below the letter. Arabic

writing has four major characteristics that

distinguish it from other languages: (a) writing is

from right to left, (b) most letters are connected in

both print and handwriting, (c) letters have slightly

different forms depending on where they occur in a

word, (d) Arabic script consists of two separate

“layers” or writing, a basic skeleton made up of

consonants and long vowels, and the short vowels

and other pronunciation and grammatical markers.

2.2 Surface Computers in Language

Learning

The benefits of multimodal tabletop displays for

educational applications seem endless. However,

few studies have specifically examined the cognitive

and pedagogical benefits of multimodal tabletop

displays. Finding related literature specifically for

early childhood education and language learning

was even more challenging. Similarly, a variety of

writing apps is available for tablet PCs (e.g.,

ReadinRockets.org provides a list of the top 9

writing apps). However, literature is still missing on

the systematical use of similar applications for

tabletops in formal education.

Research reports encouraging results so far.

Kerne et al., (2006) discusses the roles for

interactive systems enabled by touch screen devices

in supporting creative processes and aiding in idea

formation. The touch screen devices facilitate the

collection and manipulation of images, texts, and

voice annotations in a composition space. As

documented in Piper (2008), the use of multimodal

tabletop displays, as a rich medium for facilitating

cooperative learning scenarios, is just emerging.

Morris et al., (2005) examined the educational

benefits of using a digital table to facilitate foreign

language learning. The application allowed four

language learners to sit at the tabletop display and

cooperatively categorize facts about various Spanish

speaking countries.

The horizontal form factor of a multitouch

tabletop surface provides a unique opportunity for

shared interfaces allowing multiple people to

simultaneously interact with the same

representation. The use of touch technology was

essential in our project, since kindergartners usually

lack the ability to use a computer. This, along with

the shared interface that would enhance peer

interaction, made the use of tabletop surface

computers a better choice for our context. One

obvious drawback for using this kind of technology

is the high cost of the system (especially since we

needed 5 tables to accommodate the whole class).

However, one should also consider the fact that this

type of technology is gaining ground and it is

expected to reach a wider audience and that could

also mean a drop in prices. In addition, the ability to

transfer part of the material or even have future

versions of the project suitable for student-owned

tablet computers could also provide argumentation

for such a costly solution.

3 METHOD

3.1 Participants

The study was conducted in a private kindergarten

school in Qatar. Students were grouped into several

classes of, approximately, 20 students. One of these

classes was assigned by the school to participate in

the project activities, taking into account schedule

flexibility, space requirements, and parents’ consent.

Our class had 18 Qatari students (9 boys and 9

girls). All students were between 5 and 6 years old

and they were enrolled in the ‘Arabic Language’

course. Students were native speakers of the Qatari

dialect, but novices in MSA. The goal of the course

was to teach students basic linguistic skills in MSA:

vocabulary development, letter recognition and

writing, and pronunciation. The total population of

the class was present only 8 times in the 9 weeks for

various reasons (e.g., illness), while most of the

times the actual population was 16-17 students.

3.2 Design

The study lasted 9 weeks and during that time the

instructional goal was to teach students the

standalone form of the Arabic letters. The research

design follows an empirical case-study approach.

Listening, discussion, writing, and gaming activities

were used throughout the semester to complement

the introduction of a new letter.

Usually, a new letter was introduced by the

teacher during the listening and discussion sessions.

Next, the writing activities would follow, and later

the educational games. The study utilized

observation and system log files to assess students’

performance and attitudes during writing.

3.3 Material

The writing activities were performed in two ways:

on paper, and on the surface computers.

CSEDU2014-6thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

434

3.3.1 Writing Activity on Paper

For the on-paper activity, the students used A4-size

sheets. A grid filled with dashed outlines of an

Arabic letter was on the each sheet and students had

to trace the dashed letter with a black pencil. The

students were able to use erasers and the activity was

over when the entire sheet was written. This writing

activity was considered a closed-type one.

The students were sitting in desks for this

activity. The sheets were not part of the new

curriculum, but the typical instructional tools used

by the school.

3.3.2 Surface Computers

The tabletop surface computers we use in the project

(http://www.samsung.com/us/business/displays/digit

al-signage/LH40SFWTGC/ZA - referred in the rest

as ‘table’) have a 40” touch screen that can

recognize more than 50 simultaneous touch points

making it possible for several students to interact

and participate in the same activity. In addition, the

size of the screen is large enough to divide the

interface in smaller areas and have activities with 4

students per table. The students were standing up

around the table while using it.

The technology used by the table is based on

infrared detection and not on touch itself, having

both pros and cons for our activities. By basing

touch detection on shadow recognition, the table was

able to interact with tangibles. For example, placing

an object on top of a button is similar to pressing the

button. On the other hand, relying on infrared

resulted in a number of unintentional touches (e.g.,

loose clothes creating shadows on the table).

3.3.3 Writing Application for Surface

Computers

Figure 1 shows the interface of the writing

application for the surface computers. The

application provides a writing pad to each of the 4

students siting around the table. Each pad resembles

a typical notepad with lines and a white background

that contains: a written letter with and without

arrows that show the correct way of writing, several

outlined letters for the students to trace, and empty

space for writing the letters without scaffolding.

Writing can be performed either by touching the

tabletop directly with a finger, or by using an object

like a brush. Either way, we fixed the thickness of

the written strokes at 3 pixels for better results and

clearer outcome.

Each writing pad comes with five tools: the

writing mode tool that can be used to switch

between write/erase mode, the undo tool for erasing

the last written stroke, the color picker for selecting

the color of writing, and the three lines and the two

lines tools to change the number of the lines and the

size of the letters appearing in the pad. In the

beginning of the curriculum, the teacher may advise

students to write letters using the two-line pads, as it

would be easier for novice students to write bigger

letters.

Figure 1: Writing application. 1: Letter bar; 2: Writing

pad; 3: Write/erase mode; 4: Undo; 5: Color picker; 6:

Three lines; 7: Two lines.

Every time the students select a letter from the

letter bar or change the number of lines, the strokes

written on the pad are stored in a local image file

and the pad is cleared. No personal information is

recorded and students’ anonymity remains intact.

The activity is open-ended and students can keep

writing and erasing for as long as they want.

3.4 Procedure

Students have the Arabic Language course four days

per week, at different hours. The class typically lasts

40 minutes, however, because students have to

switch classrooms between classes and since there is

not always a break between classes, the actual

duration of the class is usually 30-35 minutes.

Typically, the students were engaged in a writing

activity (on paper or on the tables) every time a new

letter was introduced. The class was controlled by

the school teacher, while the principal investigator

of the project was also in the classroom to observe

and take notes. Although specific guidelines were

provided for each class by the new curriculum, the

teacher very often had to adapt the schedule to

address, mostly, time issues. Students were supposed

to write the letter both on paper and on the tables.

However, time limitations dictated skipping one or

the other mode for some of the letters.

Students used the writing application on the

tables at least once per week, spending

TeachingtheArabicAlphabettoKindergarteners-WritingActivitiesonPaperandSurfaceComputers

435

approximately 5-10 minutes for each session. For

the first 4 letters, students participated in the on-

paper activity before doing the on-table activity. The

two different modes were used on different dates.

After the fourth letter, the procedure was switched

and the on-table activity was performed before the

on-paper one. The reason for this was that we

wanted to examine whether the order in which the

students learn how to write a new letter affects them

in any way.

The students were distributed to the 5 available

tables in the classroom by the teacher. Although

organizing students into groups of 3-4 persons was

mostly done randomly, factors such as gender,

interpersonal relationships, and general student

performance were often taken into account by the

teacher, in order to have a balanced distribution.

Group formation and students’ spots were changing

in each class, and, while it was not encouraged,

students changing spots during a class was not

forbidden either. Since the writing application

contained 4 writing pads, each table could support

up to 4 students.

We decided to give students paint brushes to

write on the tables instead of having them using their

fingers. This decision aimed at two things. First, we

believed that it would feel more natural for the

students to write holding a tool resembling a pencil.

Moreover, supporting students’ skills in holding a

pencil was also a learning goal for the kindergarten.

Second, holding a brush for writing diminished

significantly the number of accidental touches, since

there was now a distance between the table surface

and students’ forearms.

The use of paint brushes was highly accepted by

the students. Specifically, a few weeks into the study

we asked students to start writing using their fingers.

After a few minutes, the students started asking for

the brushes, stating that they prefer writing with

them. One should take into account that by that time

the students were using the tables for additional

activities in the curriculum, apart from writing (e.g.,

educational games), where they would only use their

fingers.

3.5 Data Analysis

To evaluated students’ performance and attitudes in

the writing activities, we used three sources of data.

First, we received photocopies of the paper sheets

the students used for the on-paper activity. Students’

names were covered to preserve their anonymity.

The second source of information was the log files

collected from the 5 tables used in the classroom. As

we mentioned earlier, the writing application was

capturing students’ strokes on the tables producing

image files. At the end of the 9 weeks, this massive

volume of images was analyzed and compared to the

respective paper sheets. Finally, the principal

investigator of the project attended every class and

took notes throughout the 9 weeks, underlining

important events and issues that helped us

interpreting the rest of the data.

4 RESULTS

During the 9-week span covered by the study, the

students learned the first 12 letters of the Arabic

alphabet (from [ أ ] to [ ز ], considering ‘alif’ and

‘alif with hamza’ two different “letters”). After

discarding empty images and scribbles, we collected

752 images from the tables.

Students practiced the writing of the first 4 letters

on paper and then on the tables. Results between

paper and tables were similar up to that point, with

no distinct differences in students’ writing or

penmanship. In addition, the students were able to

familiarize themselves quickly with the tables and

minimize unintentional touches.

After the fourth letter, students practiced writing

on the tables first and on paper second. What we

observed was that after that point students felt more

and more comfortable with writing letters. At that

point students’ behavior in class was increasingly

positive as they accepted the various aspects of the

new curriculum (e.g,. listening sessions, educational

games, discussion sessions). However, when it

comes specifically on their attitudes towards the

writing activity, students’ comfort level was evident

by two facts, the appearing of drawing and the use of

more colors.

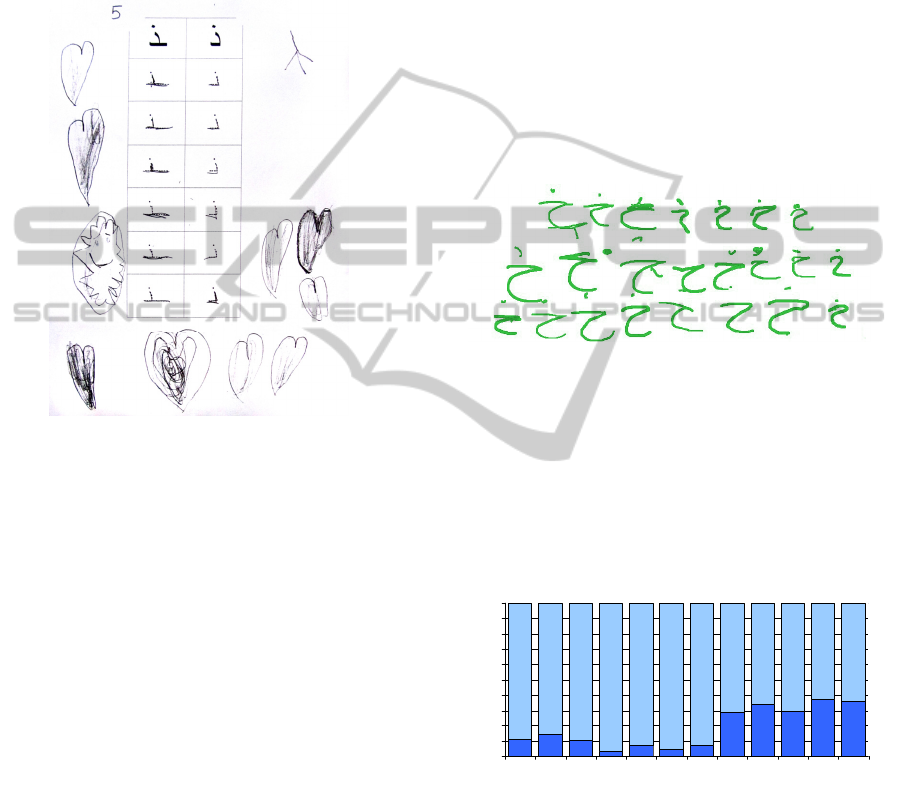

Figure 2: Student drawings on the writing application.

Students started drawing pictures, both on the

tables and on the remaining space of the paper sheets

after finishing writing the letters. The first pictures

appeared in the tables in the fifth letter covered by

the new curriculum, the ‘thaa’ [ ث ]. Two students

used the shape of the letter as the mouth, eyes, and

nose of a figurine (Fig. 2).

CSEDU2014-6thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

436

After that point, the number of drawings increased

gradually with more students drawing flowers,

hearts, houses, and items that start with the target

letter (finding items that start with a specific letter

was an important discussion topic during the

introduction of a new letter). In the next letter,

drawings appeared also on the paper sheets and after

that it was a common sight (Fig. 3),

Figure 3: Student drawings on paper sheet for the 10th

letter (‘dhaal’ [

ذ ]).

At the same time, students working on the tables

started using the color picker tool more, thus adding

different colors. This action suggests that student

were now more engaged in the activity, as they were

trying to make their writing more appealing. This

option was not available for the on-paper writing,

since students had to use pencils.

While writing a letter was an individual activity,

when working around the tables, students started

collaborating by helping each other adding more

colors, erase unwanted strokes, and selecting the

right letters to write. The same did not happen

during the on-paper writing, since that activity was

more structured and closed-type.

One issue we observed was that, in the

beginning, students were writing the letters with

strokes from left to right. This is usually the

preferred way for languages that read from left to

right. However, the proper way of writing a letter in

Arabic is from right to left and from top to bottom.

English is the primary language of instruction in

Qatar (in kindergartner, a student has 1380 minutes

of teaching in English and 320 minutes in Arabic,

per week). Thus, it was expected that writing would

be affected by the teaching of English. Up until the

letter ‘jiim’ [ ج ], the students were using the wrong

way. However, after that they started writing

correctly. A major reason for this, other than

repetitive instruction and the arrows that appear next

to the letters in the writing pad, was the shape of the

letter that forced them to start from the correct side,

while the letters up to that point allowed them to

start from both sides.

After the positive feedback we received, having

the students working on the tables first, we decided

to keep this order for the rest of the curriculum.

Students’ ease and confidence in writing was

apparent, as they started gradually to fill the whole

writing pad in the activity, moving from the 2-lines

pad to the 3-line pad on their own (Fig. 4).

Figure 4: Student writing on the table for the 9th letter

(‘khaa’ [خ ]).

Specifically, results showed a few tries with the

3-line pad since the beginning (Fig. 5). However,

most of the images showed only unsuccessful

efforts, since students were not yet familiar. On the

contrary, starting at the 8th letter (‘khaa’ [خ]),

students started using the 3-line pad more often,

filling the whole pad most of the times.

0.00

10.00

20.00

30.00

40.00

50.00

60.00

70.00

80.00

90.00

100.00

a

lifwh

alif

baa

t

a

t

ha

a

jii

m

ha

kh

a

a

daa

l

dhaal

raa

z

aa

y

Figure 5: Usage percentage of 2-line (light) and 3-line

(dark) pads.

5 DISCUSSION

In general, students developed a very positive

attitude towards the project and the writing tasks.

Having students practicing on the tables first had a

significant effect, as they became more relaxed and

TeachingtheArabicAlphabettoKindergarteners-WritingActivitiesonPaperandSurfaceComputers

437

confident. We argue that the characteristics of the

tables were responsible for this finding. The open-

ended nature of the writing application allowed

students to be more creative. Writing was not about

tracing dashes on a paper anymore. In addition, the

ability to easily erase part, or the whole, of the

writing pad with a single touch was a cleaner and

easier option than the erasers used on paper,

providing also an infinite supply of virtual sheets.

Students were not afraid to make a mistake, since it

was easy for them to erase it. This also resulted in

the high volume of images collected.

The traced letters and the arrows in the writing

pad were there to assist students. However, most of

the space was left blank. Students did not complain

about that. On the contrary, they took the

opportunity to write freely. After they changed their

attitudes towards writing, they started feeling more

comfortable with the paper as well.

Regarding the novelty effect, the tables were,

indeed, something new for the students. However, as

we mentioned earlier, students of this age are

already familiar with touch technologies and their

excitement for a technological tool itself does not

last long. In other words, students’ enthusiasm for

the tables was useful in the beginning, but it was not

the reason for sustaining a positive attitude

throughout the study. More than the technology

effect, what the tables did was to change the learning

experience for the students. Students were standing

up and they could move from one table to the other.

Peer interaction and, in some cases, peer

collaboration were boosted. We believe that this

affected students more than the technology itself in

the long run.

In time, students became more confident. The

increase of 3-line pads provides evidence on

students’ performance. However, confidence in

students in the study was evident also in other

activities of the project. As the teacher noted,

students in the project class were more talkative and

outgoing than students in other classes. This was of

course the result of a instructional design utilizing

many different learning activities, with writing being

one of them.

We need to clarify that we are not suggesting the

complete replacement of the on-paper with a

technological one. Holding a pencil and writing on a

paper are two essential skills for young learners.

Nevertheless, the use of this technology provided us

with new opportunities in supporting enthusiasm and

engagement, while teaching writing to 5-year-olds.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work has been funded by a grant from QNRF

(Qatar National Research Fund), NPRP Project 4-

1074-5-164 entitled “Advancing Arabic Language

learning in Qatar”. The authors would like to thank

Christos-Panagiotis Papazoglou and Sachin Mousli

for their contribution in the developing phase.

REFERENCES

Ferguson, C. (1991). Epilogue: Diglossia Revisited,

Southwest Journal of Linguistics 10 (1), 214.

Ibrahim, Z. (2000). “Myths About Arabic Revisited.” Al-

Arabiyya 33, 13-27.

Ibrahim, Z. (2008a). Lexical Separation: A Consequence

of Diglossia, Cambridge University Symposium,

Cambridge.

Ibrahim, Z. (2008b). Language Teaching and Technology,

in Linguistics in an Age of Globalization, editors,

Zeinab Ibrahim, Sanaa A. M. Makhlouf.

Cairo:AUCPress, 1-16.

Ibrahim, Z. (2009). Beyond Lexical Variation in Modern

Standard Arabic. London: Cambridge Scholars

Publishing.

Kerne, A., Koh, E., Choi, H., Dworaczyk, B., Smith, S.,

Hill, R. & Albea, J. (2006). Supporting Creative

Learning Experience with Compositions of Image and

Text Surrogates. In E. Pearson & P. Bohman (Eds.),

Proceedings of World Conference on Educational

Multimedia, Hypermedia and Telecommunications

2006, 2567-2574. Chesapeake, VA: AACE.

Morris, M.R., Piper, A.M., Cassanego, T., and Winograd,

T. (2005). Supporting Cooperative Language

Learning: Issues in Interface Design for an Interactive

Table. Stanford University Technical Report.

Papadopoulos, P.M., Karatsolis, A., and Ibrahim, Z..

(2013). Learning activities, educational games, and

tangibles: Arabic language learning in the ALADDIN

project. In Proceedings of the 17th Panhellenic

Conference on Informatics (PCI '13). ACM, New

York, NY, USA, 98-105.

Piper, A.M. (2008). Cognitive and Pedagogical Benefits of

Multimodal Tabletop Displays. Position paper

presented at the Workshop on Shared Interfaces for

Learning.

ReadingRockets.org, Top 9 Writing Apps. Retrieved from:

http://www.readingrockets.org/teaching/reading101/wr

iting/literacyapps_writing.

Saiegh-Haddad, E. (2003). Linguistic distance and initial

reading Acquisition: The case of Arabic diglossia.

Applied Psycholinguistics, 24, 431-451.

Saiegh-Haddad, E. (2004). The impact of phonemic and

lexical distance on the phonological analysis of words

and pseudowords in a diglossic context. Applied

Psycholinguistics, 25, 495-512.

CSEDU2014-6thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

438

Saiegh-Haddad, E. (2005). Correlates of reading fluency

in Arabic: Diglossic and orthographic factors. Reading

and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal: An

Interdisciplinary Journal, 18, 559-582.

Saiegh-Haddad, E. (2007). Linguistic constraints on

children's ability to isolate phonemes in Arabic.

Applied Psycholinguistics, 28, 605-625.

TeachingtheArabicAlphabettoKindergarteners-WritingActivitiesonPaperandSurfaceComputers

439