Challenges of Critical and Emancipatory Design Science Research

The Design of ‘Possible Worlds’ as Response

J. Marcel Heusinger

Institute for Computer Science and Business Information Systems, University of Duisburg-Essen,

Universitaetsstr. 9, Essen, Germany

Keywords: Critical and Emancipatory Research, Design Science, Possible Worlds, Design Theory.

Abstract: Popper’s (1967) ’piecemeal social change’ is an approach manifesting itself in science as critical and eman-

cipatory (C&E) research. It is concerned with incrementally removing manifested inequalities to achieve a

’better’ world. Although design science research in information systems seems to be a prime candidate for

such endeavors, respective projects are clearly underrepresented. This position paper argues that this is due

to the demand of justifying research ex post by an evaluation in practical settings. From the perspective of

C&E research it is questionable if powerful actors grant access to their organization and support projects

which ultimately challenge their position. It is suggested that theory development based on a synthesis of

justificatory knowledge is a complementary approach that allows designing realizable responses to C&E

issues–the design of ’possible worlds’ (Lewis, 1986) as basis for C&E design science research.

1 INTRODUCTION

Critical and emancipatory (C&E) research projects

are one of three application areas of information

systems research (ISR) (Iivari, 2007). However,

within ISR in general and design science research in

information systems (DSRIS) in particular, there is a

clear lack of such projects (Carlsson, 2010; Myers

and Klein, 2011). This is puzzling because DSRIS

with its aim of changing existing structures and

processes (Iivari, 2007, 2010; Purao et al., 2010;

Sein et al., 2007) seems to be a prime candidate for

this endeavor. This is most obvious in the research

stream which conceptualizes information systems

(IS) as socio-technical systems (e.g., Carlsson, 2007,

2010; Carlsson et al., 2011; Hevner, 2007; Hevner,

et al., 2010; Österle et al., 2010, 2011; Venable,

2006; Walls et al., 2004). This stream conceives

information and communication technology (ICT)

applications as an element embedded in an action

system, comprising human beings and processes,

and does not, as the much narrower view, exclude

almost anything but the ICT application (e.g.,

Gregor, 2009; Kuechler and Vaishnavi, 2012a,

2012b; Nunamaker et al., 1991; Peffers et al., 2008).

Although both conceptualizations inevitably

transform action systems to IS or change existing IS,

the broader perspective not only recognizes these

changes in composition and structure, it also allows

to deliberately plan them. This can, in reference to

Lewis (1986), be called the design of ’possible

worlds’, which were introduced to ISR by Frank

(2009). As the idea of a nomologically ’possible

world’ is a prerequisite for questioning existing

structures and processes (Frank, 2009; Zelewski,

2007), it provides the basis for C&E projects

concentrating upon the identification and removal of

manifested injustices (Robson, 2002). In addition,

DSRIS has the unique potential to form the

methodological foundation for building means to

overcome the identified injustices.

Correspondingly, it seems worthwhile inves-

tigating how DSRIS can be leveraged for C&E

research. This position paper therefore sketches the

idea of an approach focusing on the design of

’possible worlds’ as a response to C&E issues. One

part of the thesis advocated in the present paper is

that a ’realist synthesis’ (Pawson, 2006) is a

theorizing technique, which allows to gather

justificatory, design-relevant knowledge from

practical, theorizing, and theoretical ISR as well as

from relevant reference disciplines and that this

body of knowledge informs the selection and devel-

opment of two mid-range design theories, viz.

information systems design theories (ISDTs) (Walls

et al., 1992) and design-relevant explanatory and

339

Marcel Heusinger J..

Challenges of Critical and Emancipatory Design Science Research - The Design of ‘Possible Worlds’ as Response.

DOI: 10.5220/0004568403390345

In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS-2013), pages 339-345

ISBN: 978-989-8565-60-0

Copyright

c

2013 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

predictive theories (DREPTs) (Kuechler and

Vaishnavi, 2012a). The second part of the thesis is

that theorized ‘possible worlds’ represent a self-

contained C&E research project.

Outlining the position underpinning the

development of a corresponding approach is highly

relevant because it reflects the methodological self-

conception of DSRIS. However, relevance is a

characteristic attributed by the target audience

(Frank, 2006), who has to pass the final judgment.

The primary audiences of this position paper are

scientists, especially those who want to conduct

C&E projects as well as, but to a lesser extent, those

concerned with theory development in DSRIS.

The remainder is structured as follows: In the

succeeding section two anticipated responses to the

above-mentioned thesis are presented and discussed.

Based on this preparatory work, the third section

puts forward three arguments outlining the approach

for designing ’possible worlds’, which is currently

being developed by the author. The final section

concludes the discussion.

2 CHALLENGES OF C&E

RESEARCH

DSRIS sets out as a paradigm bridging both,

‘relevance’ and ‘rigor’. Responses to the thesis

stated in the previous section evolving from those

concerns seem to be the most serious. Therefore, this

section deals with two respective counterclaims: (1)

artifacts need to be rigorously evaluated to justify

the ’effectiveness’ or ’validity’ of the implied claim

and (2) relevant research deals with problems and

opportunities articulated in practice.

The first counterclaim seems to be the most

pressuring as almost all DSRIS approaches demand

an evaluation (e.g., Becker, 2010; Carlsson, 2010;

Hevner et al., 2004; Kuechler and Vaishnavi, 2008,

2012a; Nunamaker et al., 1991; Österle et al., 2010,

2011; Peffers et al., 2008; Venable, 2006). The goal

of an evaluation is to assess the efficacy or

consequences of the artifact’s instantiation in use

(Gregor, 2009) by either employing empirical-

quantitative (Iivari, 2010) or interpretive (Hevner

and Chatterjee, 2010) methods. Instantiation and

eval-uation are mandatory activities for a valid

research project (Riege et al., 2009). This is common

tenor of DSRIS: from more general instructions such

as Hevner et al.’s (2004) third guideline (i.e., “[t]he

utility, quality, and efficacy of a design artifact must

be rigorously demonstrated via well-executed eval-

uation methods”) to the more specific demands of

Kuechler and Vaishnavi (2012a) in theory

development (i.e., the “[v]alidation of the artifact

generates information that is used to assess the

correctness of the entire reasoning /circumscription

chain”) (see also Niehaves, 2007; Hevner, 2007;

March and Vogus, 2010; Nunamaker et al., 1991;

Venable, 2006; Österle et al., 2010).

The ultimate concern is the ’effectiveness’ or

’validity’ of the claim(s) manifested in the artifact,

that is, the evaluation is performed to justify all non-

evident or unshared assumptions embodied in the

artifact (Frank, 2010). In sum, the answer to how

novel research results are justified, the central

question of the context of justification (Ladyman,

2007), in DSRIS is verificatory, like the answer of

the empirical-quantitative tradition (Zelewski,

2007). Justification through ’post-construction eval-

uation’ is well-established, but not perfect. There is

room for complementary approaches such as a

’within-construction justification’.

An argument for this pluralistic perspective of

justification can be derived from difficulties

associated with the conventional approach. The

central challenge originates from the ’amplified

contingency’ (Frank, 2006) of DSRIS’s unit of

analysis leading to the insight that “the evaluation

process in design science is task and situation

specific” (March and Vogus, 2010). In other words,

the evaluation of the effectiveness is spatially and

temporally bound to a specific social context. This

corresponds to the second moment of the scientific

enterprise, the moment of ’open-systemic appli-

cation of theory’ (Bhaskar, 2008). In the ’moment of

theory’, the first moment, knowledge is gained in

controlled environments (i.e., closed systems such as

laboratories), which is then leveraged to measure or

predict events in uncontrollable environments (i.e.,

open systems such as organizations). As it is

impossible to control all influencing variables to

isolate the effects of specific causes within open

systems, observed events and their magnitude are

always the result of multiple amplifying and/or

curtailing influences. Because of the contingency of

the context, the ’practical/technological utility’

(Niiniluoto, 1993) ascertained in the evaluation in

one context, does not guarantee practical utility in

another. Furthermore, the suggestion to exclude

trail-and-error descriptions from research reports to

preserve the reader’s motivation (Chmielewicz,

1994) makes it impossible to reconstruct and explain

processes in open systems–a prerequisite to derive

transcontextual knowledge. This in turn has the

consequence that neither the possibility of

ICEIS2013-15thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

340

transferring an artifact to another context nor the

effectiveness of this transfer can be explained

scientifically; they are based on experience or

’assumed rationality’ (Bhaskar, 2008). Finally,

focusing on ’practical utility’ at the expense of the

first moment’s ’epistemtic utility’ (Niiniluoto, 1993)

inhibits eliminating hypotheses from the body of

knowledge (Bunge, 1966; Chmielewicz, 1994),

because the practical application of the artifact and

its successful evaluation does not give an indication

of the truth of the embedded theoretical propo-

sitions (Bunge, 1966). For example it might be

possible that only some part of the theoretical

knowledge embedded in the artifact holds in practice

or the evaluation is successful despite false

theoretical statements (i.e., spurious correlation).

This in turn maintains the (insufficient) state of the

knowledge base which forces DSRIS to “rely on

intuition, experience, and trial-and-error methods”

(Hevner et al., 2004) or ’assumed rationality’.

Relevance in DSRIS, as the basis from which the

second counterclaim develops, is mainly concerned

with the grounding of a DSRIS project’s purpose in

practical problems and opportunities (Hevner, 2007;

Hevner et al., 2004; Österle et al., 2010; Rossi and

Sein, 2003). These practice demands articulated by

’important stakeholders’, predominantly managers

responsible for deciding if organizational resources

are committed to the construction, procurement, and

usage of artifacts (Carlsson, 2007; Hevner and

Chatterjee, 2010; Mertens, 2010), enter DSRIS

projects in form of goals or context-specific

requirements. According to the postulate of the

’absence of value judgments’, which should ensure

objectivity, justification has to be free from value

judgments (Chmielewicz, 1994). A common inter-

pretation of this demand is to be personally detached

from values and solely focus on selecting the

’objectively’ most effective means to achieve given

goals. This move is possible because values have no

binding force (Niiniluoto, 1993). In reference to

Habermas (1987) this perspective can be called

’purposive or means-end rationality’. An extension

of this type of rationality–’normative rationality’–

would discuss goals and means in reference to

commonly shared and acceptable social values.

Such an extended perspective seems reasonable,

because science in general and applied sciences in

particular have considerable societal consequences

or side-effects. North (1990), awarded with the

Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences in

1993, for example, argues that introducing new

technology often leads to the “deliberate deskilling

of the labor force”, that is, highly skilled employees,

with high bargain power, are substituted with less

skilled and less powerful employees (for further ICT

related arguments see Fountain, 2001; Stahl, 2009).

Chmielewicz (1994) argues that it is hard to

accept that researchers, despite these societal

consequences, work on goals and means without a

normative position. He further argues that, because

researchers’ obligations are different from those of

politicians and managers, they should consider the

normative implications of their research. Similarly,

Niiniluoto (1993) notes that a researcher “contrib-

uting to applied science is morally responsible for”

his or her contribution. The exclusion of ’normative

rationality’, by solely focusing on ’purposive

rationality’ implies that human beings, an immanent

part of IS, are merely treated as objects. To some

degree and in special circumstances such a

perspective might be acceptable for analytical

purposes; however, it is a serious deficit if normative

considerations are completely excluded, especially

from applied disciplines. It not only makes the

discipline morally questionable, it also confines

intellectual curiosity—the source of important

scientific problems (Bunge, 1966)—to purposive

rationality; it makes demarcation of DSRIS and

consulting/design practice fuzzy; and it neglects the

duty of scientists to enlighten society (Albert, 1972).

This is not a call to fundamentally revise the

foundations of the discipline and its methodological

repertoire, but to recognize the inherent ’imperfect

obligation’. To make ISR more accountable to one

of its largest stakeholders, viz. society at large, the

issues considered in DSRIS need to be extended.

Within the next section the idea of a complementary

approach focusing on the design of ’possible worlds’

as solution to the identified issues is sketched.

3 THE DESIGN OF ‘POSSIBLE

WORLDS’ AS RESPONSE

One implication of the previous discussion is that

C&E projects in DSRIS are inevitably theorizing

efforts. Therefore, it seems vital to relate the

proposal to theory development in DSRIS, i.e., the

framework proposed by Kuechler and Vaishnavi

(2012a). In particular, two minor, closely related

extensions to address the above-mentioned issues

are suggested: a methodological and a conceptual.

Based on these extensions, the final part of this

section sketches an idea to distinguish possible and

utopian worlds, to address utopism as further

possible counterclaim.

ChallengesofCriticalandEmancipatoryDesignScienceResearch-TheDesignof`PossibleWorlds'asResponse

341

Kuechler and Vaishnavi (2012a) provide a list of

techniques used in theory development, which needs

to be complemented by an additional research

strategy that takes the peculiarities of C&E DSRIS

into account: the design of ‘possible worlds’ requires

a methodological foundation that allows justification

within construction, primarily because it seems to be

unlikely that those in power grant access to their

organization and support a project, such as a C&E

project, which ultimately challenges their position.

Within policy design and evaluation, a discipline

concerned with interventions in action systems, and

as such quite close to DSRIS, a successfully applied

research strategy is provided by Pawson (2006).

Based on earlier works (Pawson and Tilley, 1997;

Tilley, 2000), he develops a ’realist synthesis’,

which allows gathering design knowledge for social

interventions. Although this technique is mainly

concerned with policy interventions, which do not

necessarily entail ICT, there are no obstacles to

include ICT and fruitfully apply it in DSRIS (see

Carlsson, 2007, 2009, 2010; Carlsson et al., 2011). It

is suggested that this technique provides the basis

for a ‘with-construction’ justification, because it

synthesizes justificatory knowledge from practical

and theoretical research, which can be leveraged in

the design of ‘possible worlds’.

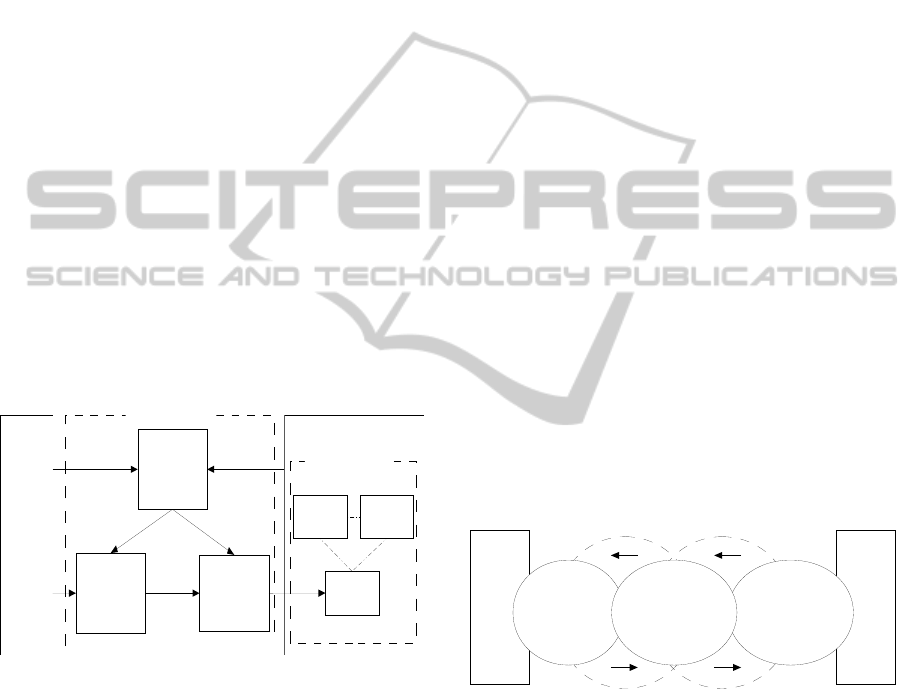

Figure 1: The Relationship between DRCT, DREPT,

ISDT, and Information Systems (modified from: Kuechler

and Vaishnavi (2012a)).

The discussion in the preceding section further

indicates that designed ICT applications do not exist

in a vacuum, but are embedded in an application

domain. This suggests two extensions of Kuechler

and Vaishnavi’s (2012a) framework: (1) a broader

view of IS, comprising people and processes in

addition to ICT applications; and (2) the inclusion of

the socio-historical context which can account for

the ’path dependency’ (David, 1985) of action and

socio-technical systems. Both these extensions are

depicted on the right side of figure 1. A second

conceptual extension is the inclusion of design-

relevant context theories (DRCTs), which capture

the results of the above-mentioned synthesizing

efforts. They are similar to what Kuechler and

Vaishnavi (2012a) define as DREPT, however,

DRCTs are not issue-centered like DREPTs, but

describe the context that specify the meta-

requirements in ISDTs (Walls et al., 1992) and

influence the selection of DREPTs for the devel-

opment of ISDTs. For example, Walls et al. (1992)

derive their “how to manage”, which enters into the

meta-requirements, from (i) “how people should

manage” and (ii) “how people manage”. Whereas (i)

indicates the connection between kernel theories and

DRCTs, (ii) refers to the connection between IS and

DRCTs. Understanding available options for

intervening with an ICT application in an IS and

assess the potential success requires identifying

relevant high-level institutional (e.g., country-

specific and international policies) and historical

influences (e.g., societal norms) as both shape the

effectiveness of ICT applications. Furthermore,

DRCTs also capture possible challenges in “how to

manage” for which DREPTs, such as the ones

discussed by Kuechler and Vaishnavi (2012a), are

selected to integrate features into ICT applications,

which allow overcoming these issues. Hence,

DRCTs not only influence the development of

ISDTs, they also connect multiple appropriate

DREPTs used in their development. This supports

the ’artifact’s mutability’ (Gregor and Jones, 2007).

Figure 2: Three Roles of Information Systems

Researchers.

These extensions provide the basis for the design

of ‘possible worlds’. Generally, ‘possible worlds’

are too complex to be achieved in a single step and

(therefore) require multiple intermediate

interventions, each creating a different context. The

various ‘context shifts’, eventually culminating in

the ‘possible world’, are captured by DRCTs. For

example, an obstacle to a ‘possible Open Access

(OA) world’ might be the concern about the review

Design-relevant

explanatory/

predictive

theory (DREPT)

Information

Systems

Design Theory

(ISDT)

Socio-historical context

Kernel

Theory

---

Tac t ic

Theory

Mid-Range Theories

Design-relevant

context theory

(DRCT)

People

Processes

ICT

application

Information System

P

r

a

c

t

i

c

e

Practical Information

Systems Research

working

hypotheses

context-configuration

effectiveness

design

theories

kernel

theories

Reference Disciplines

Pure Research

Theorizing Information

Systems Research

ICEIS2013-15thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

342

quality, which causes authors to publish their articles

in closed access journals. A simple, successful

intervention is disclosing the reviewers’ names to

provide an additional incentive. Introduced into a

particular context this intervention transforms the

context to one without the quality concern; however,

it leaves other issues untouched (e.g., high costs of

OA journals), which can be addressed by ICT-based

interventions. Following Gregor (2009) and Iivari

(2010) it is argued that such theorizing projects

constitute self-contained research projects, even

without a post-construction evaluation. Instead, each

context shift is justified, as far as possible, in

reference to appropriate synthesized research results.

Propositions for which appropriate studies are not

yet available have to be labeled as ’working

hypotheses’ (Frank, 2010), the subject of further

pure or theoretical research (see figure 2). The

results of such efforts are later (re-)integrated into

DRCTs via kernel theories. Furthermore, as the

synthesized justificatory knowledge focuses on

lower-level propositions, the total effect, assumed to

lead to the desired ‘possible world’, has to be tested

and refined in practical research. The gained insights

and context-specific adaptions or case

differentiations (context-configuration effectiveness

in figure 2) are the basis for further synthesizing,

eventually leading to more robust and refined

DRCTs.

Finally, to avoid the utopism counterclaim, a

potential allegation in response to the inclusion of

working hypotheses, it has to be shown that the

’possible world’ is in fact possible. This requires to

justify that the change leading the desired ’possible

world’ is potentially realizable (Frank, 2009).

Following Chmielewicz (1994) this can be called the

realization hurdle: is the proposed alternative

realizable or possible? The synthesis needs to justify

that this hurdle can be overcome by providing

evidence for the following five questions

(Chmielewicz, 1994): is the change (1) logically, (2)

theoretically (based on natural and social laws), (3)

instrumentally (technological), (4) economically,

and (5) normatively possible? The amount of

justificatory evidence gathered to answer these

questions determines how likely it is to realize the

’possible world’. Ideally, sufficient evidence is

provided for all these issues, in a ’real’ theorizing

project, however, the effort has to be aligned with

the intention as well as the available resources, i.e.,

only conceptually possible ‘possible worlds’, as

subset of all logically possible ‘possible worlds’,

tends to be of interest to C&E DSR.

4 CONCLUSIONS

The main argument put forward in the position paper

is that the conventional conceptualization of DSRIS,

especially the demand to evaluate an instantiated

artifact in a practical setting, tends to disadvantage

C&E projects. The principal reason is that powerful

actors will not support projects endangering their

position. The accustomed response of researchers is

to detach themselves from given goals and focus on

the practical problems and opportunities articulated

by the powerful. This neglects the (imperfect)

obligation to consciously consider the social

consequences of technological interventions.

Although such a move might be acceptable in

certain circumstances, a discipline completely

excluding C&E endeavors is morally questionable.

Therefore, it was suggested to extend the

methodological foundation of DSRIS in such a way

that these issues can be addressed. It was argued that

exploring the design of ’possible worlds’ is a fruitful

direction for identifying complementary approaches.

A brief sketch of a method based on the synthesis of

justificatory knowledge from practical and

theoretical research was given. Based on the quoted

literature and the arguments put forward in this

position paper, a detailed procedure for the design of

’possible worlds’ is currently being developed by the

author.

REFERENCES

Albert, H. (1972). Konstruktion und Kritik. Hamburg, DE:

Hoffmann and Campe.

Becker, J. (2010). Prozess der gestaltungsorientierten

Wirtschaftsinformatik. In H. Österle, R. Winter & W.

Brenner (Eds.), Gestaltungsorientierte Wirtschafts-

informatik (pp. 13–17). Nuremberg, DE: Infowerk.

Bhaskar, R. (2008). A Realist Theory of Science (2nd).

Abingdon, OX, UK: Routledge.

Bunge, M. (1966). Technology as Applied Science.

Technology and Culture, 7(3), 329–347.

Carlsson, S. A. (2007). Through IS Design Science

Research: For Whom, What Type of Knowledge, and

How. SJIS, 19(2), 75–86.

Carlsson, S. A. (2009). Critical Realist Information

Systems Research. In M. Khosrow-Pour (Ed.),

Encyclopedia of Information Science and Technology

(pp. 811–817). Hershey, PA, USA: IGI Global.

Carlsson, S. A. (2010). Design Science in IS: A Critical

Realist Approach. In A. R. Hevner & S. Chatterjee

(Eds.), Design Research in Informat-ion Systems (pp.

209–233). New York, NY, USA: Springer.

Carlsson, S. A., Henningsson, S., Hrastinski, S., & Keller,

C. (2011). Socio-technical IS Design Science

ChallengesofCriticalandEmancipatoryDesignScienceResearch-TheDesignof`PossibleWorlds'asResponse

343

Research: Developing Design Theory for IS

Integration Management. Information Systems and E-

Business Management, 9(1), 109–131.

Chmielewicz, K. (1994). Forschungskonzeption der

Wirtschaftswissenschaft. Stuttgart, DE: Poeschel.

David, P. (1985). Clio and the Economics of QWERTY.

The American Economic Review, 75(2), 332–337.

Fountain, J. E. (2001). Building the Virtual State:

Information Technology and Institutional Change.

Washington, DC, USA: Brookings Institution Press.

Frank, U. (2006). Towards a Pluralistic Conception of

Research Methods in Information Systems Research.

ICB Research Report (No. 7).Essen, DE.

Frank, U. (2009). Die Konstruktion möglicher Welten als

Chance und Herausforderung der Wirtschaftsinfor-

matik. In J. Becker, H. Krcmar & B. Niehaves (Eds.),

Wissenschaftstheorie und gestaltungsorientierte WI

(pp. 161–173). Heidelberg: Physica.

Frank, U. (2010). Zur methodischen Fundierung der For-

schung in der Wirtschaftsinformatik. In H.Österle, R.

Winter & W. Brenner (Eds) Gestaltungsorientierte

Wirtschaftsinformatik (pp. 35-44). Nuermberg, DE:

Infowerk.

Gregor, S. (2009). Building Theory in the Sciences of the

Artifical. In Proceedings of DESRIST’09 (pp. 1–10).

New York, NY, USA: ACM Press.

Gregor, S. & Jones, D. (2007). The Anatomy of a Design

Theory. JAIS, 8(5), 312–335.

Habermas, J. (1987). Reason and the Rationalization of

Society: Theory of Communicative Action. Frankfurt

am Main, DE: Suhrkamp (German).

Hevner, A. R. (2007). The Three-Cycle View of Design

Science Research. SJIS, 19(2), 87–92.

Hevner, A. R., & Chatterjee, S. (2010). Design Research

in Information Systems: Theory and Practice. New

York, NY, USA: Springer.

Hevner, A. R., March, S. T., Park, J., & Ram, S. (2004).

Design Science in Information System Research. MIS

Quarterly, 28(1), 75–105.

Iivari, J. (2007). A Paradigmatic Analysis of Information

Systems as a Design Science. SJIS, 19(2), 39–64.

Iivari, J. (2010). Twelve Theses on Design Science

Research in Information Systems. In A. R. Hevner &

S. Chatterjee (Eds.), Design Research in Information

Systems (pp. 43–62). New York, NY, USA: Springer.

Kuechler, W. L., & Vaishnavi, V. (2012a). A Framework

for Theory Development in Design Science Research:

Multiple Perspectives. JAIS, 13(6), 395–423.

Kuechler, W. L., & Vaishnavi, V. (2012b). Characterizing

Design Science Theories by Level of Constraint on

Design Decisions. In K. Peffers, M. A. Rothenberger

& B. Kuechler (Eds.), Proceedings DESRIST’12, Las

Vegas, NV, USA, May 14-15, 2012. (pp. 345–353).

Berlin, DE: Springer.

Ladyman, J. (2007). Ontological, Epistemological and

Methodological Positions. In T. Kuipers (Ed.),

Handbook of Philosophy of Science (pp. 303–376).

Oxford, UK: North Holland.

Lewis, D. K. (1986). On the Plurality of Worlds. Oxford,

UK: Blackwell.

March, S. T., & Vogus, T. J. (2010). Design Science in the

Management Discipline. In A. R. Hevner & S.

Chatterjee (Eds.), Design Research in Information

Systems (pp. 195–208). New York: Springer.

Mertens, P. (2010). Anspruchsgruppen der gestaltungs-

orientierten WI. In H.Österle, R. Winter & W. Brenner

(Eds.) Gestaltungsorientierte Wirtschaftsinformatik

(pp. 19–25). Nuremberg: Infowerk.

Myers, M. D. & Klein, H. K. (2011). A Set of Principles

for Conducting Critical Research in Information

Systems. MIS Quarterly, 35(1), 17–36.

Niehaves, B. (2007). On Epistemological Pluralism in

Design Science. SJIS, 19(2), 93–104.

Niiniluoto, I. (1993). The Aim and Structure of Applied

Research. Erkenntnis, 38(1), 1–21.

North, D. C. (1990). Institutions, Institutional Change and

Economic Performance. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge

University Press.

Nunamaker, J. F., Chen, M., & Purdin, T. D. M. (1991).

Systems Development in Information Systems

Research. JMIS, 7(3), 89–106.

Österle, H., Winter, R., & Brenner, W. (Eds.). (2010).

Nuernberg, DE: Inforwerk,

Österle, H., Becker, J., Frank, U., Hess, T., ... Sinz, E. J.

(2011). Memorandum on Design-oriented Information

Systems Research. EJIS, 20(1), 7–10.

Pawson, R. (2006). Evidence-Based Policy: A Realist

Perspective. London, UK: Sage.

Pawson, R., & Tilley, N. (1997). Realistic Evaluation.

London, UK: Sage.

Peffers, K., Tuunanen, T., Rothenberger, M. A., &

Chatterjee, S. (2008). A Design Science Research

Methodology for Information Systems Research.

JMIS, 24(3), 45–77.

Popper, K. P. (1967). The Spell of Plato: The Open

Society and Its Enemies. London, UK: Routledge.

Purao, S., Rossi, M., & Sein, M. K. (2010). On Integrating

Action Research and Design Research. In A. R.

Hevner & S. Chatterjee (Eds.), Design Research in

Information Systems (pp. 179–194). New York, NY,

USA: Springer.

Riege, C., Saat, J., & Bucher, T. (2009). Systematisierung

von Evaluationsmethoden in der gestaltungs-

orientierten Wirtschaftsinformatik. In J. Becker, H.

Krcmar & B. Niehaves (Eds.), Wissenschaftstheorie

und gestaltungsorientierte Wirtschaftsinformatik (pp.

69–86). Heidelberg, DE: Physica.

Robson, C. (2002). Real World Research: A Resource for

Social Scientists and Practitioner Researchers.

Malden, MA, USA: Blackwell.

Rossi, M., & Sein, M. K. (2003). Design Research

Workshop: A Proactive Research Approach. 26th

Information Systems Research Seminar in

Scandinavia, August 9-12, 2003, Haikko, FI.

Sein, M., Rossi, M., & Purao, S. (2007). Exploring the

Limits of the Possible. SJIS, 19(2), 105–110.

Stahl, B. C. (2009). The Ideology of Design: A Critical

Appreciation of the Design Science Discourse in

Information Systems and Wirtschaftsinformatik. In J.

Becker, H. Krcmar & B. Niehaves (Eds.), Wissen-

ICEIS2013-15thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

344

schaftstheorie und gestaltungsorientierte Wirtschafts-

informatik (pp. 111–132). Heidelberg, DE: Physica.

Tilley, N. (2000). Realistic Evaluation: An Overview.

Retrieved from http://evidence-based

management.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/

nick_tilley.pdf (last access: 2013-04-03).

Venable, J. R. (2006). A Framework for Design Science

Research Activities. In M. Khosrow-Pour (Ed.), Emer-

ging Trends and Challenges in Information Technol-

ogy Management (pp. 184–187). Hershey: Idea Group.

Walls, G. J., Widmeyer, G. R., & El Sawy, O. A. (2004).

Assessing Information System Design Theory in

Perspective: How Useful was our 1992 Initial

Rendition? JITTA, 6(2), 43–58.

Walls, J., Widmeyer, G. R., & El Sawy, O. A. (1992).

Building an Information System Design Theory for

Vigilant EIS. ISR, 3(1), 36–59.

Zelewski, S. (2007). Kann Wissenschaftstheorie behilflich

für die Publikationspraxis sein? Eine kritische Ausein-

andersetzung mit den ”Guidelines” von Hevner et al.

In F. Lehner & S. Zelewski (Eds.), Wissenschaftstheo-

retische Fundierung und wissenschaftliche Orientier-

ung der WI (pp. 71-120). Berlin: Gito.

ChallengesofCriticalandEmancipatoryDesignScienceResearch-TheDesignof`PossibleWorlds'asResponse

345