Towards a Semiotic Approach to Practice-oriented Knowledge

Transfer

Supaporn Chai-Arayalert and Keiichi Nakata

Henley Business School, University of Reading, Reading, U.K.

Keywords: Knowledge Transfer, Semiotic Approach, Social Constructivism.

Abstract: With the rapid growth of information and technology, knowledge is a valuable asset in organisation which

has become significant as a strategic resource. Many studies have focused on managing knowledge in

organisations. In particular, knowledge transfer has become a significant issue concerned with the

movement of knowledge across organisational boundaries. It enables the exploitation and application of

existing knowledge for other organisations, reducing the time of creating knowledge, and minimising the

cost of organisational learning. One way to capture knowledge in a transferrable form is through practice. In

this paper, we discuss how organisations can transfer knowledge through practice effectively and propose a

model for a semiotic approach to practice-oriented knowledge transfer. In this model, practice is treated as a

sign that represents knowledge, and its localisation is analysed as a semiotic process.

1 INTRODUCTION

Knowledge has become significant as a strategic

resource. The ability to leverage external knowledge

to an organisation’s own knowledge has become a

vital constituent to an organisation’s knowledge for

the reason that this second-hand experience can be

obtained more rapidly and more economically than

first-hand experience (Hamel, 1991); (Huber, 1991).

Knowledge transfer has become an important topic

in knowledge management. The effective knowledge

transfer can take place through manuals, training,

conversations, etc. However, there are limitations in

these ways of knowledge transfer as some types of

knowledge may not be directly captured and

managed, as we cannot always prepare knowledge in

a ‘transferable’ form. This paper introduces practice

as a vehicle of knowledge to be transferred. A

practice can be charaterised as the successful

routines in organisation which can be created

through integrating and combining new and existing

knowledge so as to apply knowledge effectively and

efficiently. In addition, the imitation of successful

practices may enable organisations to take advantage

of the value of practices (Bartlett and Ghoshal,

1989).

Moreover, the importance of context shapes the

transferring knowledge capacities. Although some

research addressed the issue of context in knowledge

transfer, few take context into account in their

analysis (Inkpen and Dinur, 1998). The previous

literature does not pay sufficient attention to the

importance and consequence of the context which

affects knowledge transfer. This paper places

emphasis on the social context based on the

application of semiotic approach and social

constructivism as its theoretical point of view.

Semiotic analysis helps in interpreting and making

sense of meanings afforded by different

organisations and how these meanings relate to each

other, and, in turn, to practice-oriented knowledge

transfer processes. Such an understanding supports

creation and transfer of knowledge between different

organisations and helps in defining the practice-

oriented knowledge transfer processes for

sustainable competitive advantage. To analyse such

processes, this paper introduces a model for

practice-oriented knowledge transfer. This model

features the codification of knowledge into practice,

transferring of practice, and the reconstruction of

knowledge through the interpretation of practice.

This paper is organised as follows. First, the

knowledge transfer and models are reviewed,

followed by the discussion of a semiotic view of

knowledge transfer. Then, an organisational

containment analysis of practice-oriented knowledge

transfer model is proposed, followed by discussion

and conclusion.

119

Chai-Arayalert S. and Nakata K..

Towards a Semiotic Approach to Practice-oriented Knowledge Transfer.

DOI: 10.5220/0004115001190124

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing (KMIS-2012), pages 119-124

ISBN: 978-989-8565-31-0

Copyright

c

2012 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

2 KNOWLEDGE TRANSFER

Knowledge management (KM) covers identification

and leveraging of the collective knowledge in order

to assist the organisation to gain competitive

advantage (Von Krogh and Roos, 1996). Activities

in KM consist of creating, storing or retrieving,

transferring, and applying knowledge (Von Krogh

and Roos, 1996). Knowledge transfer has become

one of the significant KM processes concerned with

the movement of knowledge across the boundaries

created by specialised knowledge domains (Carlile

and Rebentisch, 2003). It is the movement of

knowledge from one place, person or ownership to

another. Furthermore, knowledge transfer enables

the exploitation and application of existing

knowledge for the organisation’s purposes.

The early research of knowledge transfer has

viewed knowledge as an object and/or a process

which are transferred through mechanisms from one

organisation to a recipient organisation (Liyanage et

al., 2009); (Parent et al., 2007). The recipient in this

perspective can be viewed as a passive actor and it

often ignores the context in which the knowledge

transfer occurs and in which the knowledge is used

(Parent et al., 2007); (Inkpen and Dinur, 1998).

Therefore, the difficulties in knowledge transfer

remain. This is evident in models or paradigms of

knowledge transfer proposed and developed over a

number of theories (Parent et al., 2007). Among

them, practices can be seen as significant successful

routines in organisations. Some organisations apply

knowledge through an efficient integration or

combination of new and existing knowledge which

leads to a practice or a routine use of knowledge

(Nelson and Winter, 1982).

This is sometimes known as practice transfer

which is useful for replication of existing successful

practices that enables organisations to take

advantage of their value (Bartlett and Ghoshal,

1989). Szulanski (2000) studied the best practice

transfer and characterised it as imitation of an

internal practice which is well performed in the

organisation, and investigated both the context of

transfer and the characteristics of the knowledge

being transferred. The focus was on the ‘stickiness’

of knowledge to illustrate the challenges involved in

the transfer, and it was found that most of the

difficulties with knowledge transfer are derived

mainly from the receiving unit. However, Inkpen

and Darr (1998) reported that organisations face

problems in transferring practices across

organisational units. What is emerging here is the

focus on practices as a key feature of knowledge

transfer. To address this, this paper introduces a new

perspective of knowledge transfer based on semiotic

analysis. In the following section, we describe

organisational semiotics and Peirce’s model of

semiosis. Then, knowledge transfer as semiosis is

discussed.

3 A SEMIOTIC VIEW OF

KNOWLEDGE TRANSFER

This section discusses the relationship between

knowledge transfer and the practice based on a

semiotic approach. It begins by describing

organisational semiotics starting from Peirce’s

model of semiosis, followed by an exploration of the

practice-oriented knowledge transfer through

semiosis.

3.1 Organisational Semiotics

Semiotics is study of signs in relation to objects and

actions. As a branch of semiotics, organisational

semiotics (OS) is a discipline which aims to study

the nature, functions, characteristics and effects of

information and communication within

organisational contexts (Liu, 2000). It defines

organisations as systems where signs are created and

used for communication and business purposes (Liu

et al., 1999). It deals with the use of signs and the

construction of shared meanings within and among

organisations (Liu, 2000). Semiosis is the process of

constructing meaning from represented signs. The

process is shown by Peirce’s triadic model of

semiosis. Semiosis contains sign, object and

interpretant (Liu, 2000). Sign is the signification

without reference to anything other than itself.

Object is the signification in relation to something

else. Interpretant meditates the relationship and

helps establish the mapping between the sign and the

object. Sign is related to its referent or object with

the assistance of the interpretant which is the

interpretation process (from sign to object). The sign

can be understood or misunderstood in different

ways depending on the interpretant. The semiosis

model can assist the analysis of knowledge transfer,

as the interactions between the sign, object and

interpretant.

3.2 Knowledge Transfer as Semiosis

We analyse knowledge transfer through the use of

practice by applying Peirce’s triadic model of

KMIS2012-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeManagementandInformationSharing

120

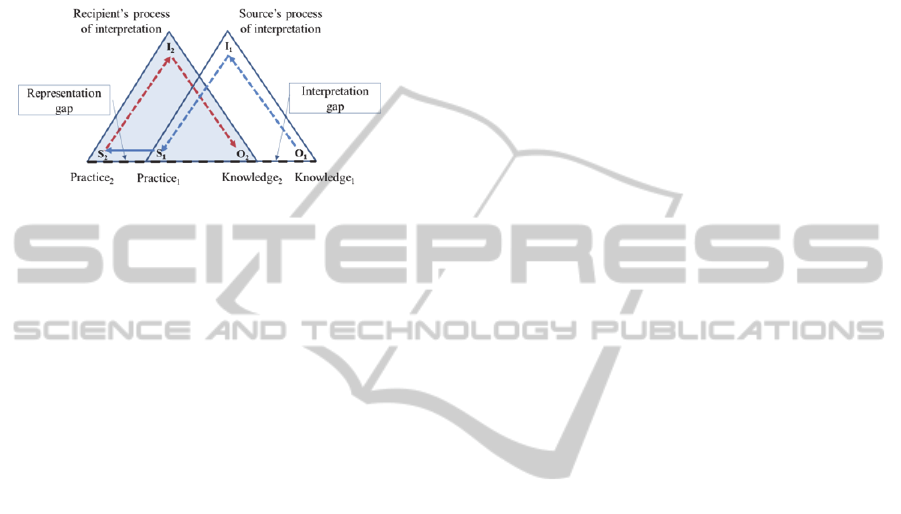

semiosis. Figure 1 presents the process of

knowledge transfer through the use of practice

between organisations (Chai-Arayalert and Nakata,

2011b). It consists of codifying knowledge,

interpreting and constructing knowledge, and

analysing influencing localisation factors. This can

be captured as semiosis.

Figure 1: Knowledge transfer as semiosis.

A sign (S) represents a practice which a source

organisation intends to use as a vehicle to transfer

knowledge to a receiving organisation. In figure 1,

S

1

represents a practice of a source organisation and

S

2

occurs when S

1

are transferred to a receiving

organisation. The representation is to describe

something or illustration of a sign. The

representation gap occurs when the two

corresponding signs that refer to the same object are

not aligned. This may occur when the practice is

transferred in the process of localisation. An object

(O) is shown as knowledge to be transferred. An

interpretant (I) is the processes of knowledge

transfer. In the source organisation, knowledge (O

1

)

is captured as a practice by a process (I

1

) of

encoding knowledge to practice. Interpretant (I

2

) is

the process of interpreting knowledge received from

the source organisation. Here we assume that

knowledge is transferred. Some factors affect the

achievement of knowledge transfer which are

represented by a gap between the knowledge to be

transferred in the source organisation (O

1

) and

transferred knowledge at the receiving organisation

(O

2

). Based on Peirce’s triadic model of semiosis,

we analyse and identify the possible gap as the

interpretation gap. This gap shows the difference of

knowledge between source and receiving

organisations. It leads to a displacement of object

when an understanding of the objects differs and can

result in a distorted understanding of the intended

meaning.

Therefore, it is important to address these two

semiosis gaps. Employing the semiosis model can

analyse the two processes that might occur in

knowledge transfer, both the process of encoding

knowledge to practice and decoding knowledge

from practice. In the next section, we explain a

practice-oriented knowledge transfer model

framework.

4 AN ORGANISATIONAL

CONTAINMENT ANALYSIS OF

THE PRACTICE-ORIENTED

KNOWLEDGE TRANSFER

MODEL

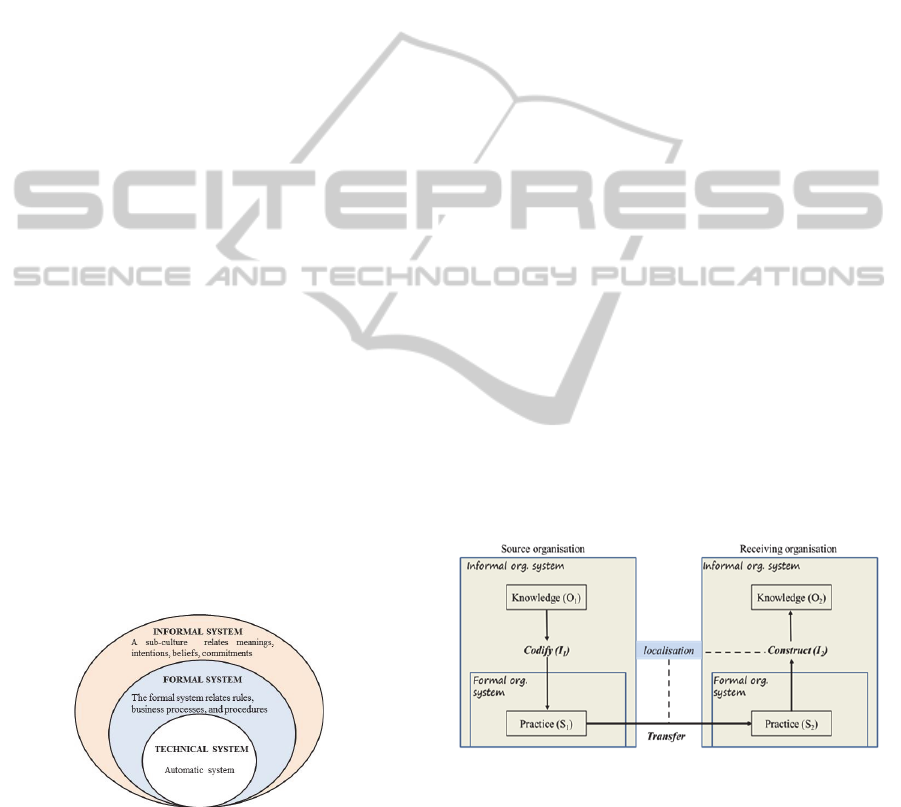

This section we analyse the proposed knowledge

transfer model using the notion of organisational

containment analysis in organisational semiotics

(figure3).

4.1 The Source’s Process of Knowledge

Codification

We begin by modelling the process of representing

knowledge as practice. We employ Peirce’s triadic

model to understand this process. As can be seen in

figure 1, this treats knowledge (object) to be

something which is carried by a practice (sign).

We illustrate this process as representing

knowledge as practice. To analyse the relationship

of knowledge and practice based on the semiotic

approach, we relate a practice to knowledge by

clarifying the concepts of knowledge and practice,

respectively. To begin with, knowledge refers to

experiences, beliefs, values, and how we feel,

motivation and information. Some focuses on the

function or purpose of knowledge which is used for

evaluating and incorporating new experiences and

information through embedded routines, processes,

practices, and norms (Davenport and Prusak, 1998).

In Langefors’ works (1966, 1993), knowledge is

referred to something actors need to know to achieve

tasks or goals. Actors are able to achieve

knowledgeable or informed actions by acquiring

task and practice relevant knowledge (Braf, 2004).

This definition underlines how agents acquire and

share knowledge to perform organisational actions.

Agents obtain knowledge through interaction and

communication with each other, and knowledge is a

property of humans and a significant part of agents’

knowledge can be expressed and communicated by

the use of signs (Braf, 2004).

Next we examine the definitions of the practice

relating to this model. First, Nelson and Winter

(1982, p.121) define the practice as “a manifestation

of organisational capability and is therefore

TowardsaSemioticApproachtoPractice-orientedKnowledgeTransfer

121

embedded in organisational routines referring as

organisational memory. The routinisation of activity

in an organisation constitutes the most important

form of storage of the organisation’s specific

operational knowledge.” In addition, Szulanski

(1996) described that the practice closely relates to a

routine use of knowledge, reflects the shared

knowledge, and relates to the capability of the

organisation. Furthermore, some who put forward

the notion of practice which focuses on agents’

actions; the practice is “embodied, materially

mediated arrays of human activity centrally

organised around shared practical understanding”

(Schatzki, 2001, p.2). Additionally, the practice

refers to the actions performed in organisation which

is seen as practice systems (Goldkuhl et al., 2001).

In the similar vein, Cook and Brown (1999, p.387)

characterises the practice as “the co-ordinated

activities of individuals and groups in doing their

real work as it is informed by a particular

organisational or group context.” There is a research

opportunity in identifying a clear relationship

between knowledge and practice, expressed through

a social process. We establish this relationship

through the semiotic approach with the purpose of

relating practices to knowledge.

According to OS, an organisation is a social

system which is composed of cultured-cognitive,

normative, regulative elements, that together with

associated activities and resources, provide stability

and meaning to social life (Liu, 2000). Stamper’s

(1992) organisational containment analysis

illustrates a view on organisations, business

processes and IT systems(Liu, 2000). It consists of

three layers: The informal, formal and technical

(figure 2).

Figure 2: The organisational containment model.

We apply the organisational containment

analysis to understand the relationship between

knowledge and practice, and the knowledge transfer

process between the organisational systems (figure

3).

First, the organisation as a whole is considered as

an informal system, where the values, beliefs and

behaviour of individuals play important roles. We

refer to the work of Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995)

that identified that knowledge is concerned with

meanings, context-specific, depending on the

situation, created dynamically in social interaction

among people. Their work identified that knowledge

deals with beliefs, commitments, and that is to be a

part of intention. Therefore, knowledge should be

analysed as a part of the informal system. Note that

this does not exclude the situation where knowledge

is more formally captured in other two layers.

Second, the formal layer is the way individual

actions and business processes should be carried out

according to rules in the organisation. We view the

practice, as a part of the formal system, which is in

line with Goldkuhl et al. (2001) who explained that

organisations as the practice systems. According to

the definitions of practice, the practice consists of

different elements such as unwritten or written rules

of how a certain organisational function should be

conducted and the rules of practice reflect a set of

underlying values and beliefs. Therefore, the

practice is seen as a part of the formal organisational

system. Third, the technical system, which is outside

the scope of this study,

is the part of the formal

system that is automated through IT system (Liu,

2000). For the reason as mentioned above, the

organisational containment model showed how

knowledge at the informal system is encoded into

practice at the formal system. In the following

subsection, we explain how knowledge is

constructed from practice at the recipient

organisation.

Figure 3: A model of practice-oriented knowledge

transfer.

4.2 The Recipient’s Process of

Knowledge Construction

Next we examine the process of knowledge

construction on the recipient’s side based on the

organisational containment analysis of the practice-

oriented knowledge transfer (figure 3). When the

practice (sign) is transferred to the recipient, this

KMIS2012-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeManagementandInformationSharing

122

practice is interpreted and decoded (interpretant) to

construct the knowledge (object). Semiotics uses the

term ‘decode’ which means how codes are

reinterpreted. There is also no knowledge transfer

without decodification process. Knowledge must be

received by a recipient who attempt to decode

practice to knowledge. The source’s process

involves the combination of sign into codes, and the

recipient’s process relates to the interpretation of

codes in the light of specific social context.

To understand the interpretation process, we

begin by defining the interpretation as the process of

translating situations and development of models for

understanding, meaning, and assembling conceptual

schema (Daft and Weick, 1984). Furthermore, the

interpretant is one aspect of Peirce’s semiosis model

which mediates between sign and object (Liu, 2000).

The knowledge in this study context is an entity that

cannot exist without the recipient and it relates to the

actions and experiences of the recipient. It also is an

outcome of social process involving human

exchanges and interactions. Thus, this process

should be an active process that constructs

knowledge from external knowledge under the prior

experiences and social interaction with others in a

particular context.

In the reconstruction process, we employ social

constructivism which focuses on how groups of

individuals communicate and negotiate their

perspectives (Young and Collin, 2004). It is closely

related to the social context involving particular

culture and social interaction (McMahon, 1997).

According to the semiotic view, the role of practice

is treated as a vehicle of knowledge which is

contextually bound: one of the important principles

of constructivism. Likewise, a constructivism views

knowledge as localised and contextual specific.

Thus, the social constructivism and semiotic

approach have the shared notions of knowledge that

it has no meaning in the real world until it is

constructed and the meaning is affected by social

interaction (Uden et al., 2001). The construction of

knowledge in the recipient is a process that is both

constrained and enabled by the social relationships

and practices of those involved in it. This is the

opportunity to understand how members of a

receiving organisation can generate new knowledge

while simultaneously being constrained by what

they have seen before.

Here, knowledge cannot be effectively

transferred if the semiosis gaps which are analysed

using Peirce’s model are significant. First, the

‘representation gap’ occurs when some practices

cannot be transferred from source to recipient as

they are, or require significant modifications,

corresponding to the differences in representations.

This can be analysed by identifying factors that

relate to the differences at the formal organisational

systems covering the differences in rules,

regulations, laws, processes, and procedures

between source and recipient. Second, the

‘interpretation gap’ occurs when the transferred

practice is interpreted by a recipient under a

receiving context. This gap corresponds to the

difference between the reconstructed knowledge by

the recipient and the source knowledge.

When a recipient effectively internalised

knowledge through constructing their own

knowledge based on the conditions of the prior

experiences, recipient’s context, and the social

interactions, the knowledge transfer process is

completed.

5 DISCUSSION

The purpose of this paper was to introduce a model

specifically developed to aid the analysis of practice-

oriented knowledge transfer. In addition, this paper

aimed to analyse localisation factors that influence

knowledge transfer through a semiotic analysis. This

model focuses on practice as a key feature of

knowledge transfer. We applied Peirce’s triadic

model to explain this knowledge transfer process.

Furthermore, we analysed this model using an

organisational containment analysis. This model is

composed of processes involving codifying

knowledge, interpreting and constructing practices,

and analysing localisation factors.

So far this is primarily a theoretical model.

However, we are currently applying the model to

analyse a case of knowledge transfer in Green ICT,

which is an emerging discipline (Chai-Arayalert and

Nakata, 2011a). This subject is drawn from practices

being developed in the public sectors including

higher education institutions (HEIs) in the United

Kingdom which is one of the first countries to focus

on Green ICT to inform of governmental strategies

and policies (Porritt, 2010). The case study involves

HEIs in United Kingdom as a source and five

universities in Thailand as the recipients. The case

study is based on focus groups and interviews to

identify the localisation factors.

The limitation of the current approach is that

while our model delineates the role of human and

social functions in determining the effectiveness of

knowledge transfer through the use of practices,

there are other dimensions that require attention such

TowardsaSemioticApproachtoPractice-orientedKnowledgeTransfer

123

as the use of technology. The limitation may also

provide indications for future research.

6 CONCLUSIONS

An effective acquisition and management of

knowledge becomes a competitive advantage in the

organisational resources. However, these activities

are not straightforward as it depends not just on the

nature of knowledge itself but also on the process of

acquiring and assimilating it. The outcomes of this

paper are as follows. First, we applied the notion of

semiosis to assist the analysis of knowledge transfer,

as the interactions between the sign, object and

interpretant. The result explored the relationship

between knowledge and practice. Furthermore, this

semiosis model explains the process of knowledge

transfer through the use of practice and analysed the

influencing factors of knowledge transfer. Second,

we proposed a model for a semiotic approach to

practice-oriented knowledge transfer. We developed

a model for the source’s process of knowledge

codification, the recipient’s process of knowledge

construction, and the influencing localisation factors.

Through a case study of knowledge transfer, we

intend to identify key localisation factors in practice-

oriented knowledge transfer in the future work.

REFERENCES

Bartlett, C. A. & Ghoshal, S., 1989. Managing across

borders, Boston, Harvard Business School Press.

Braf, E. 2004. Knowledge: Demanded for Action - Studies

on Knowledge Mediation in Organisations. Ph.D.,

Linköping University.

Carlile, P. R. & Rebentisch, E. S., 2003. Into the black

box: the knowledge transformation cycle.

Management Science, 49, 1180-1195.

Chai-Arayalert, S. & Nakata, K., 2011a. The Evolution of

Green ICT Practice: UK Higher Education Institutions

Case Study. The 2011 IEEE/ACM International

Conference on Green Computing and

Communications. Chengdu, Sichuan, P. R. China.

Chai-Arayalert, S. & Nakata, K., 2011b. A Semiotic

Approach to Analyse the Influencing Factors in

Knowledge Transfer. In: GRANT, K. (ed.) 2nd

International Conference on Information Management

and Evaluation. Toronto, Canada: Academic

Publishing International Limited.

Cook, S. D. N. & Brown, J. S., 1999. Bridging

epistemologies: The generative dance between

organizational knowledge and organizational knowing.

Organization science, 10, 381-400.

Davenport, T. H. & Prusak, L., 1998. Working

knowledge: How organizations manage what they

know. Harvard Business School.

Goldkuhl, G., Röstlinger, A. & Braf, E.: Organisations as

Practice Systems-Integrating knowledge, signs,

artefacts and action. IFIP 8.1 Conference, 2001

Montreal. Proceedings of Organisational Semiotics:

Evolving a science of information systems, 1-15.

Hamel, G., 1991. Competition for competence and inter-

partner learning within international strategic

alliances. Strategic Management Journal, 12, 83-103.

Huber, G. P., 1991. Organizational learning: The

contributing processes and the literatures.

Organization science, 2, 88-115.

Inkpen, A. C. & Dinur, A., 1998. The transfer and

management of knowledge in the multinational

corporation: Considering context. Philadelphia, PA:

Carnegie Bosch Institute. Retrieved May, 10, 2010.

Liu, K., 2000. Semiotics in information systems

engineering, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Liu, K., Alderson, A., Shah, H., Sharp, B. & Dix, A.,

1999. Applying semiotic methods to requirements

recovery. Methodologies for Developing and

Managing Emerging Technology-Based Information

Systems, 142-152.

Liyanage, C., Elhag, T., Ballal, T. & Li, Q. P., 2009.

Knowledge communication and translation - a

knowledge transfer model. Journal of Knowledge

Management, 13, 118-131.

Nelson, R. R. & Winter, S. G., 1982. An evolutionary

theory of economic change, Belknap press.

Nonaka, I. & Takeuchi, H., 1995. The knowledge-creating

company: How Japanese companies create the

dynamics of innovation. New York: Oxford University

Press.

Parent, R., Roy, M. & St-Jacques, D., 2007. A systems-

based dynamic knowledge transfer capacity model.

Journal of Knowledge Management, 11, 81-93.

Porritt, J., 2010. Green IT a Global Benchmark: a Report

on Sustainable IT in The USA, UK, Australia and

India: Fujitsu.

Schatzki, T. R., 2001. Introduction: Practice theory. In:

Schatzki, T. R., Knorr-cetina, K. & Von savigny, E.

(eds.) The practice turn in contemporary theory.

London: Routledge.

KMIS2012-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeManagementandInformationSharing

124