The Current State of EMA and ESM Study Design in

Mood Disorders Research: A Comprehensive

Summary and Analysis

Meredith L. Wallace

1,2

, Molly H. Carter

2,3

and Satish Iyengar

1

1

Department of Statistics, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA 15260, U.S.A.

2

Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA 15213, U.S.A.

3

Department of Psychology, Xavier University, Cincinati, OH 45207, U.S.A.

Abstract. Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) and experience sampling

methods (ESM) are becoming increasingly prevalent in mood disorders research

due to their potential for capturing underlying dynamic mood processes that can-

not be observed through traditional clinical visits. There have also been recent sta-

tistical developments that allow for innovative EMA/ESM-related research ques-

tions to be answered. However, even the most sophisticated statistical methods

cannot glean accurate representations of underlying mood processes when the

data are sampled inappropriately. Unfortunately, there are few resources investi-

gators can use to make informed decisions about EMA/ESM study design. Thus,

we perform a comprehensive summary of current EMA/ESM study design meth-

ods used in mood disorders research, explore the rationale behind study design

decisions, and investigate the relationship between compliance and various study

design features. Results from these analyses are used to suggest improvements

for designing and reporting future EMA/ESM studies.

1 Introduction

Clinical researchers and psychologists base their patient evaluations and diagnoses

largely on retrospective self-report of experiences. However, this type of information

can be biased by current mood state and day-to-day and even hour-to-hour variability in

experiences and symptoms [1–3]. Because mood disorders such as unipolar depression

(DEP), bipolar spectrum disorders (BD) and disorders of mood dysregulation such as

borderline personality disorder (BPD) are defined by changes in mood state and mood

variability [4], recall bias may be a particularly salient problem in this area. As a result,

information conventionally collected in clinical settings can fail to capture the continu-

ous, dynamic processes underlying mood disorders, thereby hindering researchers’ abil-

ities to characterize disease processes that may lead to specific and effective treatments.

Furthermore, information collected in a clinical setting may not provide a sufficiently

detailed understanding of a patient’s course of illness, potentially contributing to the

high rate of misdiagnosis across mood disorders [5–9].

Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) [1,2] and experience sampling method-

ology (ESM) [10,11] are data collection methods that allow clinical researchers and

L. Wallace M., H. Carter M. and Iyengar S..

The Current State of EMA and ESM Study Design in Mood Disorders Research: A Comprehensive Summary and Analysis.

DOI: 10.5220/0003878400030016

In Proceedings of the 2nd International Workshop on Computing Paradigms for Mental Health (MindCare-2012), pages 3-16

ISBN: 978-989-8425-92-8

Copyright

c

2012 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

psychologists to capture a patient’s course of illness with greater frequency and sensi-

tivity through the use of hand-held technological devices. When studying disorders of

mood and mood dysregulation (henceforth, we will refer to them collectively as “mood

disorders”), EMA and ESM are particularly useful for capturing both the mean and in-

stability of mood [12]. EMA accomplishes this through the use of portable technologi-

cal devices, such as hand-held computers and cellular phones, to capture self-reported

measurements as they occur naturally in real time. In this way, EMA allows investiga-

tors to control timing precisely and track compliance [13]. EMA can also be used to

capture behavioral and physiological data; however, the focus herein is on self-reported

EMA. Like EMA, ESM also uses technological devices to capture data in real time;

however, ESM typically uses a digital watch or pager to prompt participants to record

their experiences in a paper-and-pencil diary [10,11]. In this manuscript we focus on

self-reported EMA and ESM, referring to them collectively as EMA.

As with any type of data collection method, EMA study design is of utmost im-

portance. In general, there is consensus that random sampling should be employed and

that the sampling frequency should match the temporal dynamics of the process of in-

terest [11,14,15]. However, there is a paucity of formal empirical evidence regarding

EMA study design methodology and rationale, particularly as it relates to the capture

of underlying mood processes. One important breakthrough study in this area was per-

formed by Ebner-Priemer and Sawitzki [14], who showed that a sampling interval of

less than 30 minutes could optimally capture underlying dynamic processes in BPD,

while intervals greater than 30 minutes could not. However, few research studies (espe-

cially those in clinical populations) are expected to support sampling intervals of less

than 30 minutes due to concerns of participant burden [14].

The field of mental health, and mood disorders in particular, could benefit from

the development of a more standardized set of EMA study design methods so that fu-

ture researchers can make more informed decisions (e.g., consider the stringency with

which clinical trials are designed and reported). As an initial step towards this end goal

we present a comprehensive summary and analysis of study design features in mood

disorders research, focusing on three specific aims:

1. Summarize the current state of EMA study design

2. Explore factors that researchers have considered when making EMA study design

decisions

3. Investigate the relationships among study design features and compliance

Results from these three aims are used to suggest ways that EMA investigators could

improve on the design and reporting of their studies.

2 Methods

To empirically describe and evaluate EMA study design in mood disorders research

it is necessary to use the actual studies, rather than manuscripts generated from these

studies, as the units of analysis. This presents a challenge because manuscripts and

studies are not related on a one-to-one basis. That is, multiple manuscripts may stem

4

from one study or, alternatively, one manuscript may analyze data from multiple stud-

ies. We employed the following strategy to develop a data base with the study as the

unit of analysis. First, we set inclusion and exclusion criteria for the types of studies that

would be considered. Second, we used literature search engines to locate manuscripts

that described studies meeting the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Third, we compared

manuscripts to determine which stemmed from the same studies and which merged data

from multiple studies. We contacted corresponding authors when questions or ambigui-

ties arose. Fourth, we used the manuscripts and additional resources from authors (e.g.,

EMA study questionnaires and protocols) to enter the study-level data. We describe

these steps in further detail below.

2.1 Study Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Study inclusion criteria were: 1) at least one subset of participants was clinically diag-

nosed with a mood disorder (BPD, DEP, or BD) and 2) an electronic ambulatory device,

including but not limited to beepers, hand-held computers, cellular phones, and wrist-

watches, was used to capture self-report data at multiple time points. Self-report EMA

may be either event-based (participant enters data before and/or after a prespecified

event occurs), prompt-based (participant enters data when prompted by a technologi-

cal device), or a combination of the two; however, the focus herein lies specifically in

prompt-based EMA because it relies heavily on a priori decisions regarding sampling

frequency. Thus, we excluded studies that did not include some type of prompt-based

EMA. We also excluded EMA case studies because of our specific focus on the use of

EMA to answer empirically-based research questions.

2.2 Search Strategy

We first aimed to identify all manuscripts arising from appropriate EMA studies by

performing literature searches in PubMed, PsycINFO, and ProQuest (Dissertations and

Theses) with the following keywords: ambulatory assessment, ecological momentary

assessment, experience sampling method, electronic diary, computer-assisted diary,

electronic momentary assessment, ecological validity, and hand-held computer. After

removing duplicate references, we performed a computerized search of the resulting

abstracts to narrow them down to those based on populations with mood disorders. Ab-

stract search terms included depression, depressive disorder, borderline, bipolar, mood

disorder, and affective disorder. All remaining abstracts were manually screened to

further identify those which stemmed from studies that fit within our inclusion and ex-

clusion criteria. The full text of each of the remaining manuscripts was then used to

determine whether the study from which it arose would be considered appropriate for

inclusion. Once the final subset of manuscripts was identified, the full text was again

examined to determine which manuscripts stemmed from the same EMA study and

which combined data from multiple EMA studies.

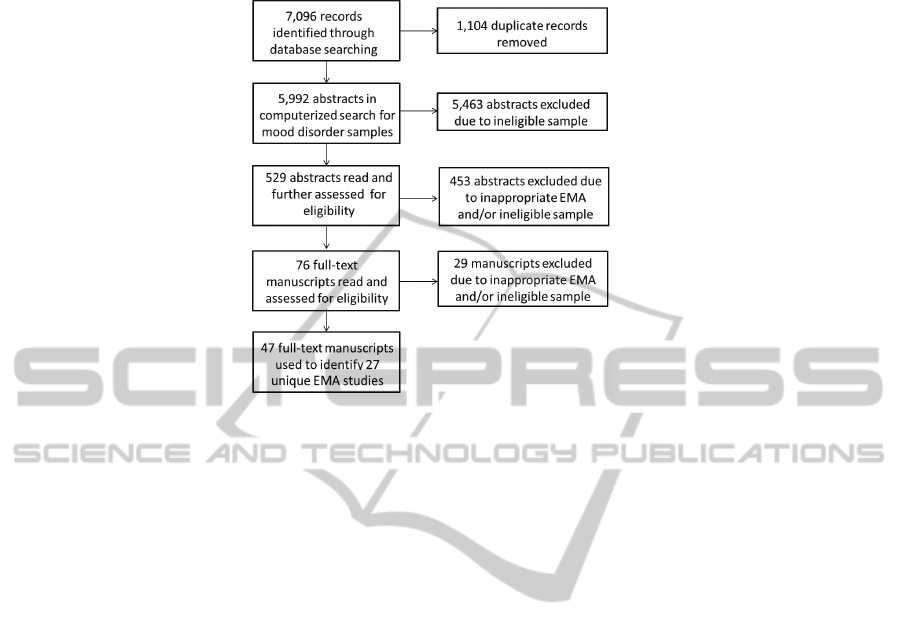

Figure 1 summarizes the search strategy and manuscript selection process. Table 1

lists the final 27 studies selected through this selection process. Because each of these

27 studies could generate multiple manuscripts, we refer to them in Table 1 by the by the

5

Fig.1. Flow diagram for manuscript and study selection.

first author and year of the earliest manuscript identified through the literature search.

Other related manuscripts are displayed in the “References” column.

2.3 Data Collection

The manuscripts referenced in Table 1 and additional author resources (e.g, EMA ques-

tionnaires and study protocols) were used to develop a data base that included: 1) study

design information, such as the sample size, duration of study, number prompts per day,

number of questions per prompt, and the type of EMA device used, 2) demographic

information for the samples used in each study, such as age and gender, 3) diagnos-

tic groups studied, 4) justification of sampling design, and 5) compliance information,

such as missing data and dropout percentages. When collecting the data from studies

that also included a randomized trial component, we only included EMA data from the

baseline weeks. This was done in an attempt to standardize the studies and also because

treatment assignment may impact measures of compliance.

2.4 Data Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to summarize the 27 EMA studies with respect to sam-

pling design and demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants (Aim 1).

To explore investigators’ rationale behind EMA study design selection (Aim 2) we first

summarized the study design justifications provided in the associated manuscripts. Be-

cause only eight of the 27 studies actually provided this explicit justification (see Table

1), we used our observed data to further explore the rationale behind current EMA study

design. This involved quantifying observed relationships among study design parame-

ters (the number of days of EMA study, the number of prompts per day, and the number

6

Table 1. First author and year of the earliest manuscript identified with each study. All other

related manuscripts are cited in the “References” column.

First Author (Year) References First Author (Year) References

Armistead, M.S. (2010) [16] Husky, M.M. (2010) [43]

Axelson, D.A. (2007)* [17–21] Links, P.S. (2007)* [44–46]

Barge-Schaapveld (1995) [22–25] Mokros, H.B. (1993) [47]

Ben-Zeev, D. (2009) [26] Myin-Germeys, I. (2003) [48–50]

Ben-Zeev, D. (2010) [27] Peeters, F. (2003) [51–54]

Biller, B.A. (2004) [28] Putnam, K.M. (2008) [55]

Bower, B. (2010)* [29,30] Stetler, C. (2004)* [56]

Campbell, J.A. (1998) [31] Stetler, C. (2005)* [57]

Conrad, A. (2008) [32] Stiglmayr, C.E. (2005) [58]

Delespaul, P. (2002) [33] Stiglmayr, C.E. (2008) [59]

Depp, C.A. (2010)* [34] Trull, T.J. (2008) [60,61]

Doyle, P.M. (2009)* [35] Wichers, M. (2010) [62]

Ebner-Priemer, U.W. (2006)* [14,36–40] Wolff, S. (2007) [63]

Glaser, J.P. (2008) [41,42]

*Reported rationale for study design

of questions per prompt) using scatter plots and Pearson product moment correlations.

Because the distributions of these variables were highly skewed, we used the natural

log transformation for all plots and calculations.

To investigate the relationships among study design features and compliance (Aim

3), we first needed to select a single compliance measure. After comparing various pos-

sibilities, we chose the percentage of unanswered prompts because it was frequently

reported and also easily constructed from other types of reported compliance statistics.

We calculated the percentage of unanswered prompts (P ) as the number of unanswered

prompts divided by the total number of possible prompts times 100. Some studies re-

ported only P

1

, the percentage of unanswered prompts based on a subset of N

1

< N

compliant participants with fewer than X% unanswered prompts. Hence, the percent-

age of unanswered prompts for the N

2

= N − N

1

participants, P

2

, was unknown

except for the fact that X % < P

2

≤ 100%. Because N

2

tended to be very small (e.g.,

one or two participants), we assumed that P

2

followed a uniform distribution and let

P

2

= .5 × (100 − X ). P was then calculated as a weighted average of the percentages

of unanswered prompts prompts for the N

1

compliant and N

2

noncompliant partici-

pants, that is, P =

1

N

(P

1

N

1

+ P

2

N

2

).

After calculating the percentage of unanswered prompts (P ), we used scatter plots

and Pearson product moment correlation coefficients to explore its relationships with

various study design features. Specifically, we focused on the number of questions per

prompt, the number of prompts per day, and the number of days of the EMA study.

Because these study design features need to be carefully balanced to reduce participant

burden, we also focused on their interactions: questions per day (questions per prompt

× prompts per day), prompts per study (promptsper day × days of study), and questions

per study (questions per prompt × prompts per day × days of study). Due to the highly

skewed distributions of all variables involved, we used the natural logs of these variables

in our plots and calculations.

7

3 Results

3.1 Aim 1: Summarize the Current State of EMA Research

Study design and demographic characteristics of the of the 27 EMA studies are summa-

rized in Table 2. In general, study participants tended to be female and Caucasian, with

a median age of 31. The study design characteristics selected by investigators (e.g., the

number of questions per prompts, number of prompts per day, and number of days of

EMA) varied widely across the 27 studies, as shown by the minimum and maximum

scores in Table 2.

In addition to selecting the number of questions, prompts, and days of EMA, inves-

tigators must also choose a method for distributing these prompts throughout the study

period. Within each day, the most common method for allocating prompts was random

blocking (e.g., divide waking hours into 6 blocks and randomly sample once during

each block); this method was used in 10 of the 27 studies (37%). Periodic sampling

with random error (e.g., sample every hour plus or minus a ranodmly drawn number of

minutes from a prespecified normal distribution) was the second most common method

for allocating EMA prompts, seen in 8 studies (29.6%). Only five (18.5%) studies used

random sampling (e.g., randomly select 10 times between the hours of 8:00 am to 10:00

pm) and only four (14.8%) studies used fixed time sampling (e.g., sample every hour

on the hour).

The method for distributing prompts throughout the study period must also take into

consideration the fact that participants are not able to answer prompts during sleep. Out

of 26 studies for which this information was known, 70.1% (n=19) set a fixed daily

interval during which prompts could occur (e.g., between the hours of 8:00 am to 10:00

pm for all participants). Other studies set a priori individualized sleep intervals tailed

to each participant’s needs (19.2%, n=5) or requested that the participant turn off the

device during sleep (7.7%, n=2).

Investigators must also determine which technological device (e.g., hand-held com-

puter, cellular phone, pager) to use to deliver each prompt. A hand-held computer, such

as a “personal digital assistant” (PDA) was used in 59.3% of studies (n = 16). The

next most frequently used technological device (37%, n=10) was a pager or wristwatch

along with a paper-and-pencil diary. One study (3.7%) used a cellular phone.

Patients with depression (major depression, minor depression, or dysthymia) were

included in eighteen studies (66.7%), patients with bipolar spectrum disorders were

included in five studies (18.5%), and patients with borderline personality disorder were

included in 9 (33.3%) studies. Other non-affective clinical groups (e.g., schizophrenia,

panic disorder) were included in four (14.8%) studies. Healthy controls were used as a

comparison group in 16 (59.3%) of the studies.

3.2 Aim 2: Explore Investigators’ Rationale behind EMA Study Design

Decisions

We first searched for explicit study design justifications in the manuscripts stemming

from each study. Overall, we identified some type of sampling justification in eight of

the 27 studies (29.64%). Two of these eight studies discussed rationale for the days on

8

Table 2. Demographic, clinical, and study design characteristics from 27 studies.

Characteristic N Observed Mean (SD) Median (Min, Max)

Demographic

Average Age 26 31.69 (11.14) 31.04 (10.01, 62.45)

% Female 24 79.08 (16.54) 78.10 (50, 100)

% Caucasian 12 65.61 (23.72) 64.70 (33.33, 100)

% Higher Education 17* 56.81 (33.39) 64.50 (0, 100)

% Married or Cohabitating 15* 35.34 (32.00) 26.37 (0, 88.24)

% Employed (Full- or Part-Time) 12* 37.40 (17.77) 43.24 (0, 55.73)

Study Design

Sample Size at Study Entry 27 78.67 (43.90) 73 (10, 164)

Days of EMA/ESM 27 9.33 (9.52) 6.79 (1, 42)

Prompts per Day 27 9.16 (9.63) 8 (1, 54)

Questions per Prompt 26 25.58 (16.91) 23 (1, 75)

Percentage of Missed Prompts 22 16.79 (10.40) 12.97 (3, 41.9)

*Among 24 studies with an average participant age > 18

which EMA sampling occurred, citing that “the weekend was chosen because it is the

time when adolescents have the greatest amount of free time and control over activities

and companions” [21] and “the same weekdays (Tuesday-Thursday) were used to have

a homogenous sample of days” [29].

The remaining six of the eight studies provided justification for the timing and/or

frequency of prompts within each day. In two different studies, Stetler et al. [56,57]

sampled cortisol levels at the same time as the self-reported EMA. Specific sampling

time intervals were chosen because they were previously found to “...adequately cap-

ture the diurnal pattern of cortisol secretion without placing undue burden on the par-

ticipants” [56] and because they were able to “...capture the early morning peak that is

part of the diurnal pattern of cortisol secretion” [57]. Ebner-Priemer and Sawitski [14]

emphasized that “the temporal dynamics of emotional-cognitive processes are largely

unknown”, and thus, their study employed multiple sampling frequencies to investi-

gate this question. Depp et al. [34] cited the “need to balance between ‘coverage’ of

affective experiences and subject burden.” Doyle [35] simultaneously employed three

different types of recording procedures “to capture mood ratings in close proximity to

the behaviors and events of interest...”. Links [44] stated that “random times were used

to approximate the daily range of a participant’s affective intensity within the context

and flow of the participant’s daily experience.”

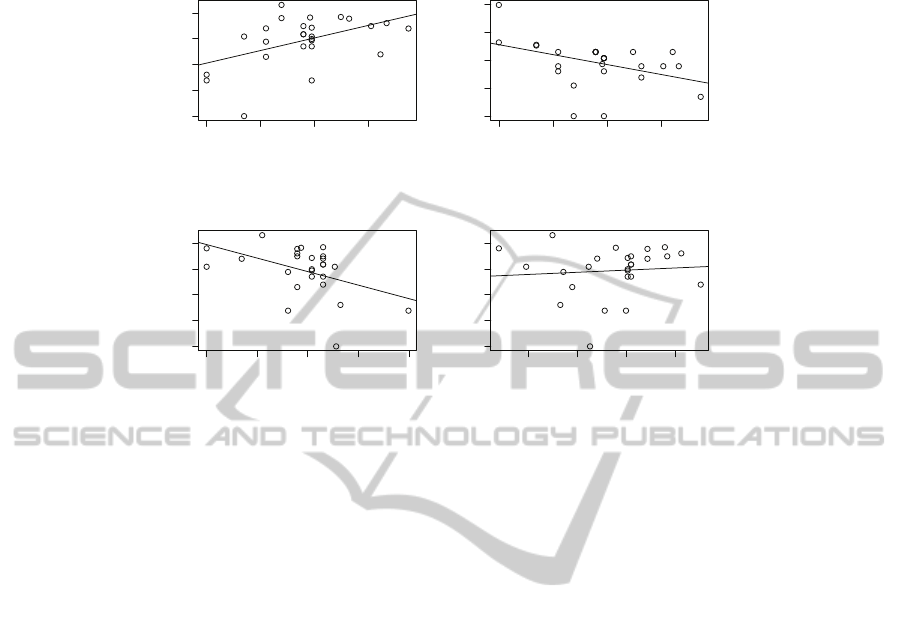

Because there were only eight studies for which an explicit sampling design ratio-

nale was found, we also explored the observed relationships among the number of days

of EMA, the number of prompts per day, and the number of questions per prompt. Be-

cause the study design variables were highly skewed, Figure 2 displays the associations

among the log-transformed study design variables (henceforth, the reader may assume

that all variables discussed are logged transformed). There was a strong negative as-

sociation between the number of questions per prompt and the number of prompts per

day (r = −.45, p = .02). Similarly, there was a strong negative association between the

number of prompts per day and the number of days of EMA (r = −.41, p = .03). There

9

0 1 2 3

0 1 2 3 4

Log of Days of EMA

Log of Questions per Prompt

r = .48; p = .01

0 1 2 3

0 1 2 3 4

Log of Days of EMA

Log of Prompts per Day

r = −.41; p = .03

0 1 2 3 4

0 1 2 3 4

Log of Prompts per Day

Log of Questions per Prompt

r = −.45; p = .02

2 3 4 5

0 1 2 3 4

Log of Total Number of Prompts

Log of Questions per Prompt

r = .08; p = .68

Fig.2. Scatter plots with least-squares regression lines displaying relationships among the log-

transformed number of questions, number of prompts, and number of days of EMA. Pearson

product moment correlation coefficients (r) and associated p-values are also displayed.

was a strong positive association between the number of questions per prompt and the

number of days of EMA (r = .48, p = .01). The positive association may reflect the

fact that more days of EMA leads to fewer prompts per day, which may in turn lead to

more questions asked at each prompt. There was no significant association between the

number of questions per prompt and the total number of prompts over the entire EMA

study.

3.3 Aim 3: Investigate Relationships among Study Design Features and

Compliance.

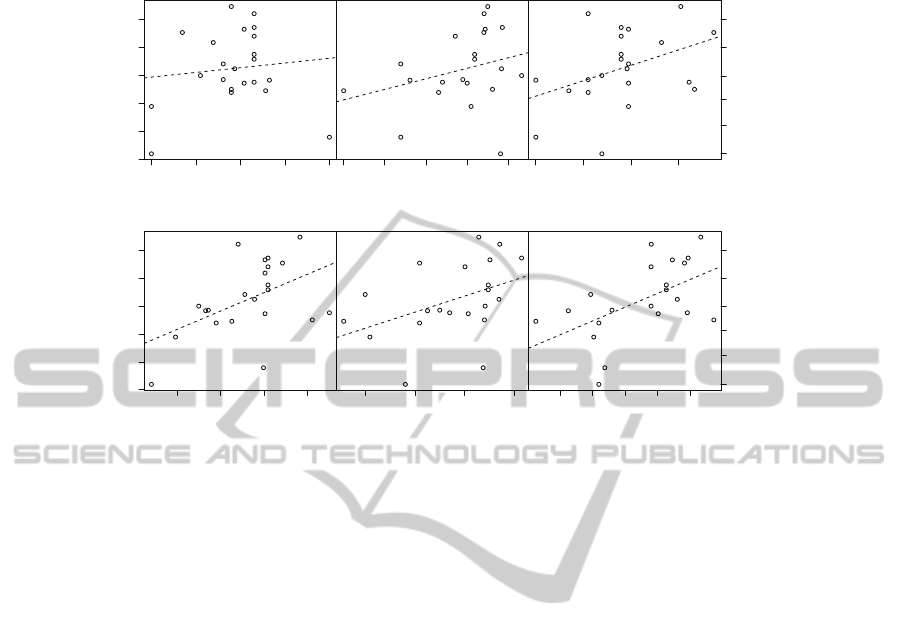

Figure 3 illustrates the relationships among the study design features and the percent-

age of unanswered prompts. The number of questions per prompt and the number of

prompts per day were not significantly associated with the the percentage of unan-

swered prompts. After removing the high but valid outlier in the number of prompts

per day (estimated 54 prompts per day [36]), there was a strong positive relationship

between the percentage of unanswered prompts and the number of prompts per day (r

= .44, p=0.05); however, the removal of this outlier only highlights the potential lever-

age of the low outliers (1 prompt per day [56,57]). There were strong and borderline-

significant positive relationships between the percentage of unanswered prompts and

both the days of EMA and questions per day (questions × prompts). There were strong

and significant positive relationships between the percentage of unanswered prompts

and both the total number of prompts (prompts × days) and the total number of ques-

tions (questions × prompts × days).

10

0 1 2 3 4

Log Prompts per Day

Log % Unanswered Prompts

r = .11, p = .62

1.0 1.5 2.0 2.5 3.0 3.5

0 1 2 3 4

Log Questions per Prompt

r = .29, p = .20

0 1 2 3

Log Days in Study

r = .41, p = .06

3 5 8 12 20 33

% Unanswered Prompts

2 3 4 5

Log % Unanswered Prompts

r = .49, p = .02

Log Prompts in Study

(Prompts*Days)

1.0 1.5 2.0 2.5 3.0 3.5

r = .42, p = .06

3 4 5 6

Log Questions per Day

(Questions*Prompts)

4 5 6 7 8

r = .54, p = .01

Log Questions per Study

(Questions*Prompts*Days)

3 5 8 12 20 33

% Unanswered Prompts

Fig.3. Scatter plots with least-squares regression lines displaying relationships between the log-

transformed study design features and the log percentage of unanswered prompts. Pearson prod-

uct moment correlation coefficients (r) and associated p-values are also displayed.

4 Discussion

The overall goal of this manuscript is to provide researchers with a comprehensive

summary and analysis of current EMA study design methods used in mood disorders

research. To attain this goal, we summarized the current state of EMA study design used

in mood disorders research, explored the rationale behind the selection of EMA study

design features, and investigated the impact of study design on participant compliance.

The results of our comprehensivesummary highlight the wide variety of EMA study

design methods that are currently used in mood disorders research. This is particularly

true regarding to the number of questions per prompt, the number of prompts per day,

and the number of days of EMA. To a large degree, this variability may be explained

by the fact that each study has its own unique goals, participants, and restrictions; thus,

each study’s design must be tailored to meet its specific needs. However, insight into

this process was only provided to the reader in 8 of the 27 studies we investigated. This

lack of detail may pose challenges for newer investigators who may want to enter into

EMA research but do not have the experience to make these decisions on their own.

It may also lead more experienced EMA researchers to use only one familiar study

design, rather than tailoring each study design to match the temporal dynamics of the

underlying process of interest.

The lack of explicit detail regarding study design rationale makes it difficult to ex-

plore which considerations are most important for EMA investigators. However, the

observed negative associations between the number of prompts per day and both the

11

days of EMA and the questions per prompt suggests that investigators do indeed con-

sider the need to balance these study design features, presumably to reduce participant

burden.

Our investigation of the relationships among study design features and participant

compliance showed that the number of study days may havea bigger impact compliance

than either the number of prompts per day or the number of questions per prompt. Not

surprisingly, the strongest observed relationship showed a positive association between

the total number of questions asked during the study (questions × prompts × days)

and the percentage of unanswered prompts. Although these relationships may not be

unexpected, their quantification is an important first step towards developing a set of

study design guidelines for future EMA research.

Although care was taken to avoid potential biases and when developing the data

base, analyzing the data, and interpreting the results, there are limitations that must

be considered. One such limitation stems from the fact that our primary unit of anal-

ysis was the study. As such, features of each study often had to be identified through

manuscripts and by discussion with the actual study investigators. When investigators

could not be reached, the full scope of the original EMA study was not always evident;

this could lead to errors in the data base due to a lack of full study descriptions in these

manuscripts. However, the fact that these study design features were not immediately

evident from the manuscripts highlights the need for a more standardized approach to

developing and reporting EMA studies.

4.1 Future Directions

When designing EMA studies, two critical considerations are to obtain quality EMA

data at the frequency necessary for modeling underlying dynamic processes and to use

a sampling scheme that will not result in undue participant burden [14]. These con-

siderations are often at odds with one another, and thus, pose challenges for EMA re-

searchers. Furthermore, the “underlying temporal dynamics” of mood disorders are still

largely unknown [14], making it difficult to select the appropriate sampling frequency

even without participant constraints.

To overcome these challenges, it will be important to address three areas of EMA

research: 1) monitor and standardize current sampling methods 2) evaluate whether

current EMA sampling methods work actually work as intended (i.e., capture true un-

derlying processes), and 3) develop new EMA sampling methods that can balance the

need to effectively capture these processes while considering participant burden. The

research presented herein is aimed at addressing the first area of research. We are cur-

rently working to address areas two and three so that future EMA investigators can

have the tools they need to answer the critical EMA-related questions, both in the field

of mood disorders specifically and in the broader fields of mental and physical health

research.

References

1. Stone, A. A., Shiffman, S., Ecological Momentary Assessment in Behavioral Medicine. An-

nals of Behavioral Medicine 16 (1994) 199–202.

12

2. Shiffman, S., Stone, A. A., Hufford, M. R.: Ecological momentary assessment. Annual Re-

view of Clinical Psychology 4 (2008) 1–32.

3. Solhan, M. B., Trull, T. J., Jahng, S., Wood, P. K.: Clinical assessment of affective instabil-

ity: comparing EMA indices, questionnaire reports, and retrospective recall. Psychological

Assessment. 21 (2006) 425-436

4. American Psychiatric Association, A. P., Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Dis-

orders IV. 1994, Washington, D.C.: Author

5. Perlis, R. H.: Misdiagnosis of bipolar disorder. The American Journal of Managed Care 11

(2005) S271–S274

6. Zimmerman, M., Ruggero, C. J., Chelminski, I., Young, D.: Clinical characteristics of de-

pression outpatients previously overdiagnosed with bipolar disorder. Comprehensive Psychi-

atry 51 (2010) 99–105

7. Zimmerman, M., Galione, J. N., Ruggero, C. J., Chelminski, I., Dalrymple, K., Young, D.:

Overdiagnosis of bipolar disorder and disability payments. The Journal of Nervous and Men-

tal Disease 198 (2010) 452–454

8. Hirschfeld, R. M. A., Lewis, L., Vorknik, L.A.: Perceptions and impact of bipolar disorder:

How far have we really come? Results of the national depressive and manic-depressive as-

sociation 2000 survey of individuals with bipolar disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 64

(2003) 161–174

9. Blacker, D., Tsuang, M. D., Contested boundaries of bipolar disorder and the limits of cate-

gorical diagnosis in psychiatry. American Journal of Psychiatry 149 (1992) 1473–1483

10. Csikszentmihalyi, M., Larson, R.: Validity and Reliability of the Experience-Sampling

Method. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 175 (1987) 526–536

11. Bolger, N., Davis, A., Rafaeli, E.: Diary Methods: Capturing Life as it is Lived. Annual

Review of Psychology 54 (2003) 579–616

12. Ebner-Priemer, U. W., Trull, T. J.: Ecological Momentary Assessment of Mood Disorders

and Mood Dysregulation. Psychological Assessment 21 (2009) 463–475

13. Barrett L. S., Barrett, D. J.: An Introduction to Computerized Experience Sampling in Psy-

chology. Social Science Computer Review 19 (2001) 175–185

14. Ebner-Priemer, U. W., Sawitzki, G.: Ambulatory Assessment of Affective Instability in Bor-

derline Personality Disorder: The Effect of Sampling Frequency. European Journal of Psy-

chological Assessment 23 (2007) 238–247.

15. Capturing Momentary, Self-Report Data: A proposal for reporting guidelines. Annals of Be-

havioral Medicine 24 (2002) 236–243

16. Armistead, M. S., Looking for Bipolar Spectrum Psychopathology: Identification and Ex-

pression in Daily Life. Unpublished thesis, University of North Carolina at Greensboro

(2010)

17. Axelson D. A., Bertocci, M. A., Lewin, D. S., Trubnick, L. S., Birmaher, B., Williamson, D.

E., Ryan, N. D., Dahl, R. E.: Measuring Mood and Complex Behavior in Natural Environ-

ments: Use of Ecological Momentary Assessment in Pediatric Affective Disorders. Journal

of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology 13 (2003) 253–266

18. Silk, J. S., Dahl, R. E., Ryan, N. D., Forbes, F. E., Axelson, D. A., Birmaher, B., Siegle, G. J.:

Pupillary Reactivity to Emotional Information in Child and Adolescent Depression: Links to

Clinical and Ecological Measures. American Journal of Psychiatry. 164 (2007) 1873–1880

19. Whalen, D. J., Silk, J. S., Semel, M., Forbes, E. E., Ryan, N. D., Axelson, D. A., Birmaher, B.,

Dahl, R. E.: Caffeine Consumption, Sleep, and Affect in Natural Environments of Depressed

Youth and Healthy Controls. Journal of Pediatric Psychology 33 (2008) 258–367

20. Forbes, E. E., Hariri, A. R., Martin, S. L., Silk, J. S., Moyles, D. L., Fisher, P. M., Brown,

S. M., Ryan, N. D., Birmaher, B., Axelson, D. A., Dahl, R. E.: Altered Striatal Activation

Predicting Real-World Positive Affect in Adolescent Major Depressive Disorder. American

Journal of Psychiatry 166 (2009) 64–73

13

21. Bertocci, M. A.: Media Use by Children and Adolescents with and without Depression:

Going it Alone? Unpublished thesis, University of Pittsburgh (2010)

22. Barge-Schaapveld D. Q. C. M., Nicolson, N. A., van der Hoop, R. G., deVries, M. W.:

Changes in Daily Life Experience Associated with Clinical Improvement in Depression.

Journal of Affective Disorders 34 (1995) 139–154

23. Barge-Schaapveld D. Q. C. M., Nicolson, N. A., Berkhof, J., deVries M. W.: Quality of

Life in Depression: Daily Life Determinants and Variability. Psychiatry Research 88 (1999)

173–189

24. Barge-Schaapveld D. Q. C. M., Nicolson, N. A.: Effects of Antidepressant Treatment on the

Quality of Life: An Experience Sampling Study. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 63 (2002)

477–485

25. Geschwind, N., Nicolson, N. A., Peeters F., van Os, J., Barge-Schaapveld D., Wichers, M.:

Early Improvement in Positive Rather than Negative Emotion Predicts Remission from De-

pression after Pharmacotherapy. European Neuropsychopharmacology 21 (2011) 241–247

26. Ben-Zeev, D., Young M. A., Madsen, J. W.: Retrospective Recall of Affect in Clinically

Depressed Individuals and Controls. Cognition and Emotion 23 (2009) 1021–1040

27. Ben-Zeev, D., Young, M. A.: Accuracy of Depressed Patients’ and Healthy Controls’ Ret-

rospective Symptom Reports: An Experience Sampling Study. The Journal of Nervous and

Mental Disease 198 280–285

28. Biller, B. A.: Examining the Utility of Ecological Momentary Assessment with Individual

Diagnosed with Depressive Disorder. Unpublished thesis, Pace University (2004)

29. Bower, B., Bylsma, L. M., Morris, B. H., Rottenberg, J.: Poor Reported Sleep Quality Pre-

dicts Low Positive Affect in Daily Life Among Healthy and Mood-Disordered Persons. Jour-

nal of Sleep Research 19 (2010) 323–332

30. Bylsma, L. M., Taylor-Clift, A., Rottenberg, J.: Emotional Reactivity to Daily Events in

Major and Minor Depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 120 (2011) 155–167

31. Campbell, J. A.: Caregivers’ Affective Attunement and Preadolescent Depression: An Eco-

logical Approach. Unpublished thesis, Chicago School of Professional Psychology (1998)

32. Conrad, A., Wilhelm, F. H., Roth W. T., Spiegel, D., Taylor, C.B.: Circadian affective, car-

diopulmonary, and cortisol variability in depressed and nondepressed individuals at risk for

cardiovascular disease. Journal of Psychiatric Research 42 (2008) 769–777

33. Delespaul, P., deVries, M., van Os, J.: Determinants of Occurrence and Recovery from Hallu-

cinations in Daily Life. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 37 (2002) 97–104.

34. Depp, C. A., Mausbach, B., Granholm, E., Cardenas, V., Ben-Zeev, D., Patterson, T.L.,

Lebowitz, B.D., Jeste, D.V.: Mobile Interventions for Severe Mental Illness: Design and

Preliminary Data from Three Approaches. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 198

(2010) 715–721

35. Doyle, P. M.: Mood Variability and Symptomatic Expression in Women with Bulimia Ner-

vosa and Comorbid Borderline Personality Disorder. Unpublished thesis, Northwester Uni-

versity (2009)

36. Ebner-Priemer U. W., Kuo, J., Welch, S. S., Thielgen, T., Witte, S., Bohus, M., Linehan,

M. M.: A Valence-Dependent Group-Specific Recall Bias of Retrospective Self-Reports: A

Study of Borderline Personality Disorder in Everyday Life. The Journal of Nervous and

Mental Disease 194 (2006) 774–779

37. Ebner-Priemer, U. W., Welch, S. S., Grossman, P., Reisch, T., Linehan, M. M., Bohus, M.:

Psychophysiological Ambulatory Assessment of Affective Dysregulation in Borderline Per-

sonality Disorder. Psychiatry Research 150 (2007) 265–275

38. Ebner-Priemer, U. W., Juo, J., Kleindienst, N., Welch, S. S., Reisch, T., Reinhard, I., Lieb,

K., Linehan, M. M., Bohus, M.: State Affective Instability in Borderline Personality Disorder

Assessed by Ambulatory Monitoring. Psychological Medicine 37 (2007) 961–970

14

39. Reisch T., Ebner-Priemer U. W., Tschacher, W., Bohus, M., Linehan, M. M.: Sequences of

Emotions in Patients with Borderline Personality Disorder. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica

118 (2008) 42–48.

40. Ebner-Priemer, U. W., Kuo, J., Schlotz, W., Kleindienst, N., Rosenthal, M. Z., Detterer, L.,

Linehan, M. M., Bohus, M.: Distress and Affective Dysregulation in Patients with Borderline

Personality Disorder: A Psychophysiological Ambulatory Monitoring Study. The Journal of

Nervous and Mental Disease 196 (2008) 314–320

41. Glaser, J.-P., van Os, J., Mengelers, R., Myin-Germeys, I.: A Momentary Assessment Study

of the Reputed Emotional Phenotype Associated with Borderline Personality Disorder. Psy-

chological Medicine 38 (2008) 1231–1239

42. Glaser, J.-P., van Os, J., Thewissen, V., Myin-Germeys, I.: Psychotic Reactivity in Borderline

Personality Disorder. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 121 (2010) 125–134

43. Husky, M. M., Gindre, C., Mazure, C. M., Brebant, C., Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Sanacora, G.,

Swendsen, J.: Computerized Ambulatory Monitoring in Mood Disorders: Feasibility, Com-

pliance, and Reactivity. Psychiatry Research 178 (2010) 440–442

44. Links, P. S., Eynan, R., Heisel, M. J., Barr, A., Korzekwa, M., McMain, S., Ball, J. S.: Af-

fective Instability and Suicidal Ideation and Behavior in Patients with Borderline Personality

Disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders 21 (2007) 72–86

45. Links, P. S., Eynan, R., Heisel, M., Nisenbaum, R.: Elements of Affective Instability As-

sociated with Suicidal Behavior in Patients with Borderline Personality Disorder. Canadian

Journal of Psychiatry 53 (2008) 112–116

46. Nisenbaum, R., Links, P.S., Eynan, R., Heisel, M.J.: Variability and Predictors of Nega-

tive Mood Intensity in Patients with Borderline Personality Disorder and Recurrent Suicidal

Behavior: Multilevel Analyses Applied to Experience Sampling Methodology. Journal of

Abnormal Psychology 119 (2010) 433–439

47. Mokros, H. B.: Communication and Psychiatric Diagnosis: Tales of Depressive Moods from

Two Contexts. Health Communication 5 (1993) 113–127

48. Myin-Germeys, I., Peeters, F., Havermans, R., Nicolson, N. A., deVries, M. W., Delespaul,

P., van Os, J.: Emotional Reactivity to Daily Life Stress in Psychosis and Affective Disorder:

An Experience Sampling Study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 107 (2003) 124–131

49. Havermans, R., Nicolson, N. A., deVries, M. W.: Daily Hassles, Uplifts, and Time Use in

Individuals with Bipolar Disorder in Remission. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease

195 745–751

50. Havermans, R., Nicolson, N. A., Berkhof, J., deVries, M. W.: Mood Reactivity to Daily

Events in Patients with Remitted Bipolar Disorder. Psychiatry Research 179 47–52

51. Peeters, F., Nicolson, N. A., Berkhof, J., Delespaul, P., deVries, M.: Effects of Daily Events

on Mood States in Major Depressive Disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychiatry 112 (2003)

203–211

52. Peeters, F., Nicolson, N. A., Berkhof, J.: Cortisol Responses to Daily Events in Major De-

pressive Disorder. Psychosomatic Medicine 65(2003) 836–841

53. Peeters, F., Berkhof, J., Delespaul, P., Rottenberg, J., Nicolson, N. A.: Diurnal Mood Varia-

tion in Major Depressive Disorder. Emotion 6 (2006) 383–391

54. Peeters, F., Berkhof, J., Rottenberg, J., Nicolson, N. A.: Ambulatory Emotional Reactivity to

Negative Daily Life Events Predicts Remission from Major Depressive Disorder. Behavior

Research and Therapy 48 (2010) 754–760

55. Putnam, K. M., McSweeney, L. B.: Depressive Symptoms and Baseline Prefrontal EEG Al-

pha Activity: A Study Utilizing Ecological Momentary Assessment. Biological Psychiatry

77 (2008) 237-240

56. Stetler, C., Dickerson, S. S., Miller, G. E.: Uncoupling of Social Zeitgebers and Diurnal

Cortisol Secretion in Clinical Depression. Psychoneuroendocrinology 29 (2004) 1250–1259

15

57. Stetler, C., Miller, G. E.: Blunted Cortisol Response to Awakening in Mild to Moderate De-

pression: Regulatory Influences of Sleep Patterns and Social Contexts. Journal of Abnormal

Psychology 114 (2005) 697–705

58. Stiglmayr, C. E., Grathwol, T., Linehan, M. M., Ihorst, G., Fahrenberg, J., Bohus, M.: Aver-

sive Tension in Patients with Borderline Personality Disorder: A Computer-Based Controlled

Field Study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 111 (2005) 372–379

59. Stiglmayr, C. E., Ebner-Priemer, U. W., Bretz, J., Behm, R., Mohse, M., Lammer, C.-

H., Anghelescu, I.-G., Schmahl, C., Schlotz, W., Kleindienst, N., Bohus, M.,: Dissociative

Symptoms are Positively Related to Stress in Borderline Personality Disorder. Acta Psychi-

atrica Scandinavica 117 (2008) 139–147

60. Trull, T. J., Watson, D., Tragessser, S. L., Jahng, S., Wood, P. K., Piasecki, T.M: Affective

Instability: Measuring a Core Feature of Borderline Personality Disorder with Ecological

Momentary Assessment. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 117 (2008) 647–661

61. Jahng, S., Wood, P. K., Trull, T. J.: Analysis of Affective Instability in Ecological Momen-

tary Assessment: Indices Using Successive Difference and Group Comparison via Multilevel

Modeling. Psychological Methods 13 (2008) 354–375

62. Wichers, M. H., Peeters, F., Geschwind, N., Jacobs, N., Simons, C. J. P., Derom, C., Thiery,

E., Delespaul, P. H., van Os, J.: Unveiling Patterns of Affective Responses in Daily Life may

Improve Outcome Prediction in Depression: A Momentary Assessment Study. Journal of

Affective Disorders 124 (2010) 191–195

63. Wolff, S., Stiglmayr, C., Bretz, H. J., Lammers, C.-H., Auckenthaler, A.: Emotion Identifi-

cation and Tension in Female Patients with Borderline Personality Disorder. British Journal

of Clinical Psychology 46 (2007)347–360

16