ELECTRONIC RECORDS MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS

The Human Factor

Johanna Gunnlaugsdottir

Faculty of Human and Social Sciences, University of Iceland, Gimli, Saemundargata, IS-101, Reykjavik, Iceland

Keywords: Human-computer interaction, User interface, Change management, Iceland, Database management systems,

Records management.

Abstract: The purpose of this paper is to present the findings of a research conducted in Iceland during the period

2001-2005 and in 2008 on how employees view their use of Electronic Records Management Systems

(ERMS). Qualitative methodology was used. Four organizations were studied in detail and other four

provided a comparison. Open-ended interviews and participant observations were the basic elements of the

study. The research discovered the basic issues in the user-friendliness of ERMS, the substitutes that

employees turned to if they did not welcome ERMS, and how they felt that their work could be shared and

observed by others. Employees seemed to regard ERMS as a groupware for constructive group work and

not as an obtrusive part of a surveillance society. The research indicated training as the most important

factor in making employees confident in their use of ERMS. The research identifies that most important

implementation factors and the issues that must be dealt with to make employees more content, confident

and proficient users of ERMS.

1 INTRODUCTION

ERMS are information systems designed to capture

and manage records in any format according to the

organization’s record-keeping principles.

The implementation and use of ERMS was

studied in recent research that was conducted in a

number of Icelandic organizations. The data

collection took place during the period 2001-2005 in

eight organizations, four public and four private

organizations. A follow-up was made in 2008.

One of the aims of the study was to discover how

employees felt working with ERMS and that is the

focus of this paper. It examines:

1. Whether employees found the ERMS user-

friendly or not.

2. What employees used as a substitute if

they did not use ERMS.

3. Whether employees objected that their

work in ERMS was being monitored or observed

by others.

There was a strong relationship between the

important implementation factors and the level of

use (Gunnlaugsdottir, 2008a; 2008b).

The following discussion is organized into five

sections starting with a presentation of the

methodology used. The interviewees expressed their

feelings regarding their work in ERMS. They are

grouped into four categories: The user-friendliness

of ERMS, informal alternatives to records

management (RM) other than using ERMS, and

monitoring by superiors and fellow employees

seeing work performed in ERMS. The paper

concludes with a general discussion of the findings.

2 METHODOLOGY AND ERMS

The aim of this part of the research was to discover

how employees in eight organizations in Iceland felt

about working with ERMS. A qualitative

methodology with a triangular approach was chosen

for conducting the research (Denzin and Lincoln,

2003; Gorman and Clayton, 1997) although it was

attempted to use quantitative measurements, as

suggested by Silverman (2005), whenever

qualitative data lent themselves to such

interpretations. Two different methods were used in

the field. Open-ended interviews were conducted

with employees (King, 1999; Kvale, 1996) and

participant observations were undertaken (Bogdan

97

Gunnlaugsdottir J. (2009).

ELECTRONIC RECORDS MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS - The Human Factor.

In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems - Human-Computer Interaction, pages 97-104

DOI: 10.5220/0002000600970104

Copyright

c

SciTePress

and Biklen, 2003).

The main data collection took place during the

period September 2001 to April 2005. The total

number of interviewees in the eight organizations

was 38. The interviewees were eight records

managers, eight managers, four computer specialists,

eight specialist and ten general office employees. A

detailed data collection took place in four

organizations which were given the pseudonyms:

Government Institution, City Organization,

Financial Institute and Manufacturing Firm. In these

organizations a number of employees were

interviewed and participant observations took place

were offices of employees were visited. In the other

four organisations that were given the names: Public

Services Office, Food Processing, Municipal Office

and Construction Firm, only the records managers

were interviewed. The workstations that were visited

during the participant observations were 140 in total.

Follow-up interviews were conducted with the

records managers in the eight organizations in the

beginning of 2008.

The eight organizations had bought four different

ERMS (D, E, F and G) with two organizations using

the same system. All of the four systems had been

evaluated and were believed to meet all of the

important requirements of the DoD5015.2-STD

(2002) – latest edition (2007), the requirements for

approved RM procedures according to the ISO

15489 standard for RM (ISO, 2001a; 2001b), and

Icelandic law. They all meet the requirements of

being ERMS (ARMA International, 2004; CECA,

2001). These ERMS were all equipped with a

classification scheme, ‘the foundation of any ERMS’

(CECA, 2008, p. 23). All of the four ERMS offered

opportunities for group work and co-operation

between employees (Coleman, 1999;

Gunnlaugsdottir, 2003; 2004; Orlikowski and

Barley, 2001).

3 THE USER-FRIENDLINESS OF

ERMS

People working in Iceland are computer literate in

general as indicated by surveys. That should make it

easier for organizations to implement electronic

information systems such as ERMS. Almost 90% of

all individuals 16-74 years use a computer and the

Internet (Statistics Iceland, 2007) and almost 100%

of Icelandic enterprises use computers and have

access to the Internet (Statistics Iceland, 2006).

User-friendliness means that employees should

be able, with limited knowledge of computers, to

learn and adopt the new work procedures and to use

the system correctly. ERMS must be user-friendly

concerning the following work procedures: Word

processing, classification of records, cataloguing or

registering of records, saving records, searching for

and retrieving records and the distribution of records

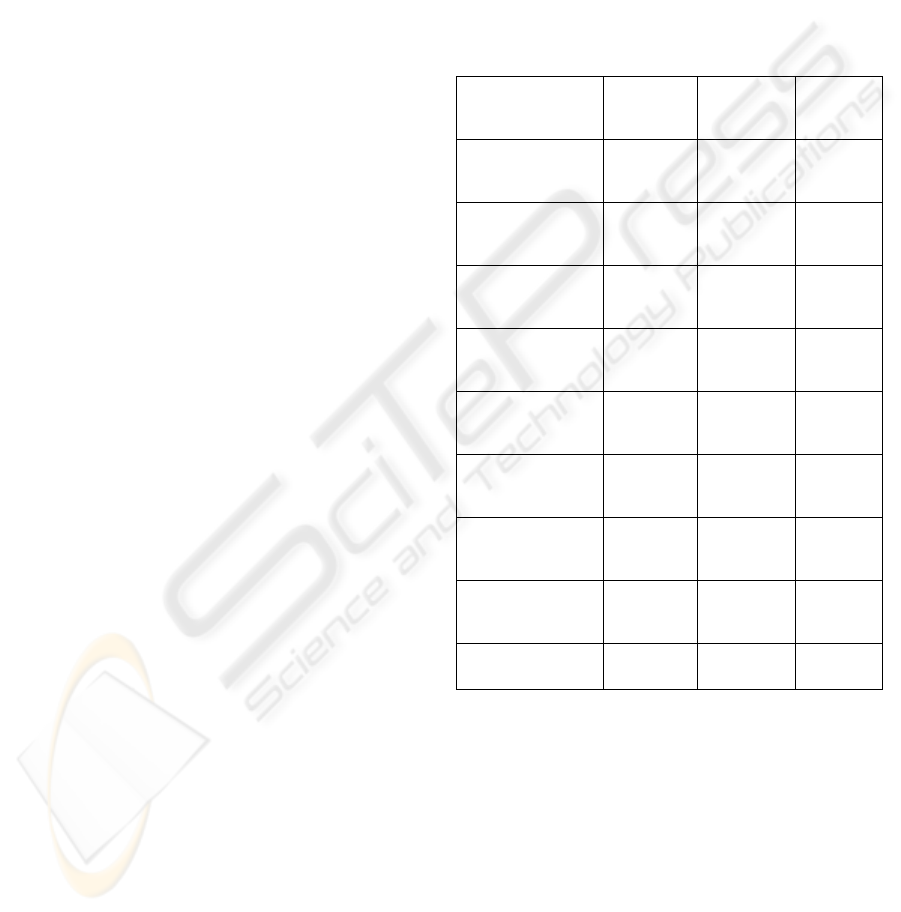

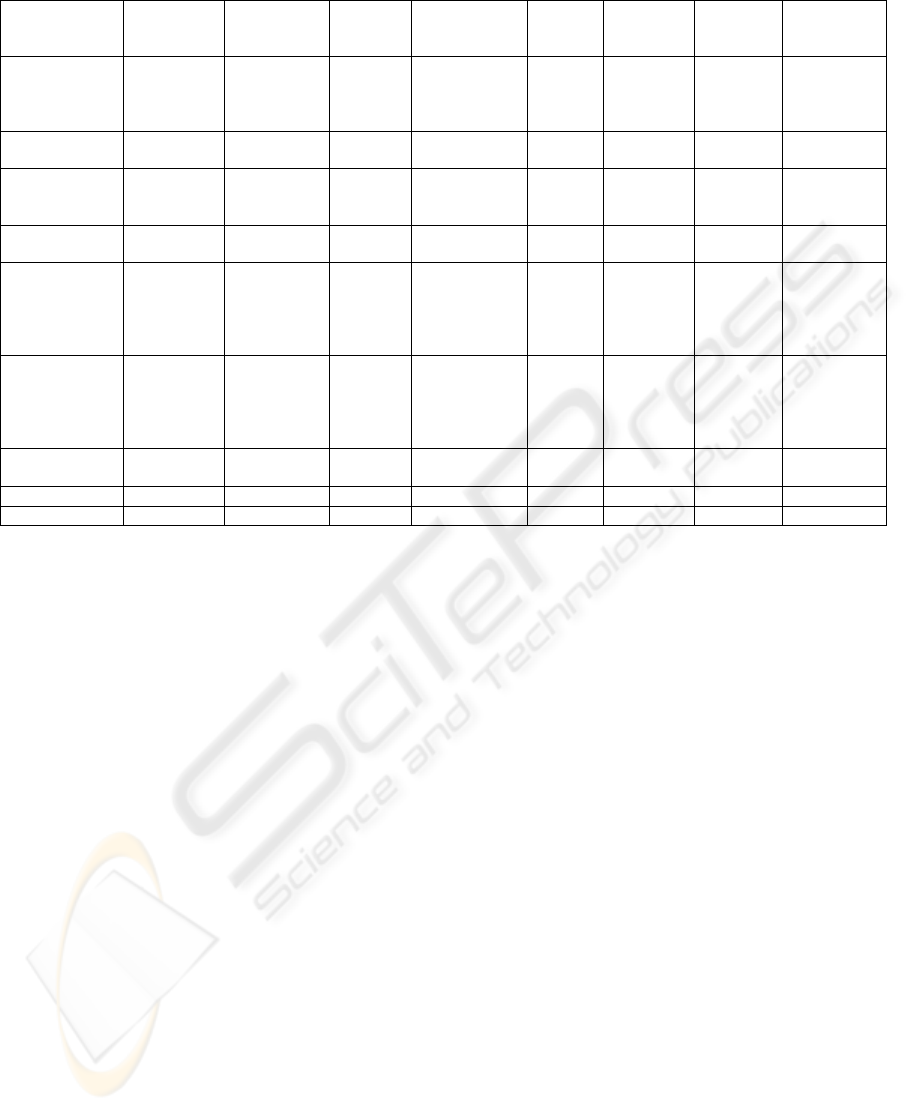

and information. Table 1 lists the number of

employees, according to organizations, whether they

felt that ERMS was user-friendly or not.

Table 1: User-friendliness of ERMS in the eight

organizations.

Organization:

*Public

**Private

User-

friendly

Not user-

friendly

Total

*Government

Institution

(System D)

10

1

11

*City

Organization

(System F)

2

5

7

**Financial

Institute

(System E)

8

0

8

**Manufacturing

Firm

(System G)

3

5

8

*Public Services

Office

(System D)

1

0

1

**Food

Processing

(System F)

1

0

1

*Municipal

Office

(System E)

1

0

1

**Construction

Firm

(System G)

1

0

1

Total 27 11 38

The first four organizations listed in Table 1

were studied in detail. Employees in two of the

organizations, the Government Institution and the

Financial Institute, found ERMS user-friendly, with

ten out of eleven and eight out of eight being of that

opinion. These were the two organizations of the

four studied in detail with the highest rate of use

among the users expected to use ERMS, 75% and

90% respectively (see Table 4). The employees in

the other two organizations, the City Organization

and the Manufacturing Firm, displayed a different

attitude. In the City organization five out of seven

employees found ERMS not user-friendly and in the

ICEIS 2009 - International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

98

Manufacturing Firm the ratio was five out of eight.

These were the two organizations of the four studied

in detail with the lowest rate of use, 25% and 15%

respectively (see Table 4).

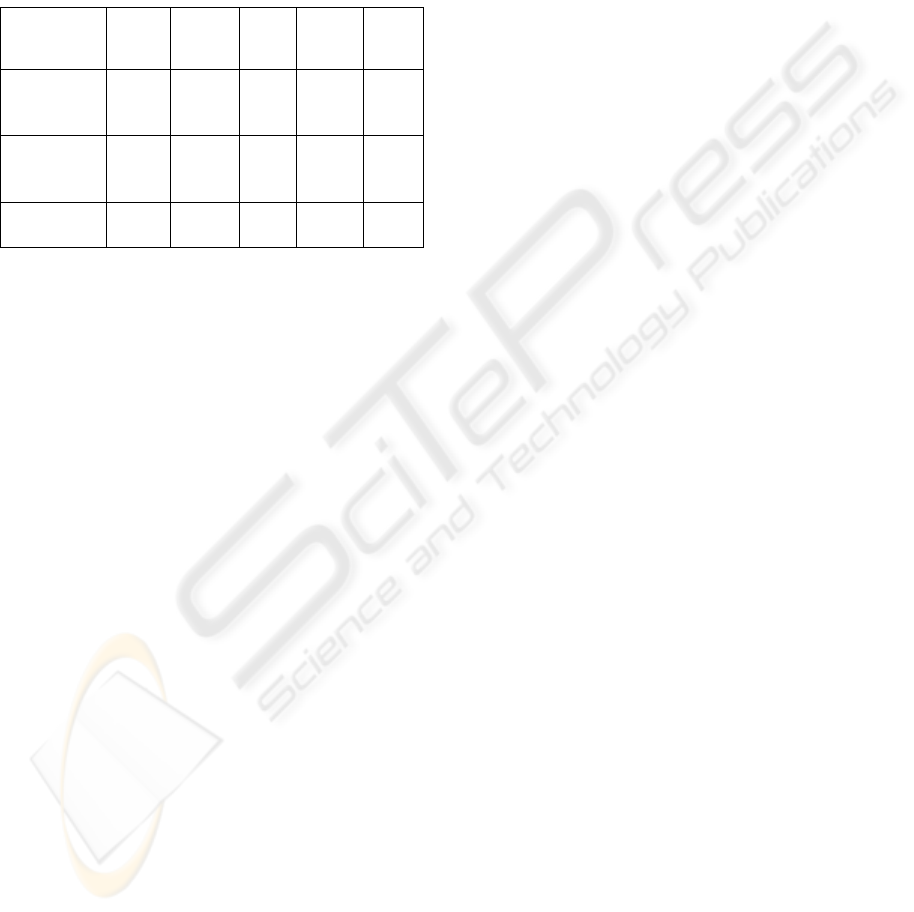

The four ERMS seem to show a different

outcome regarding user-friendliness, as shown in

Table 2.

Table 2: User-friendliness of the four ERMS according to

users of each system.

User-

friendliness

Sys. D Sys. F Sys. E Sys. G Total

User-

friendly

11 3 9 4 27

Not user-

friendly

1 5 0 5 11

Total 12 8 9 9 38

System F and System G were claimed to be not

as user-friendly as the other two. Here it must be

borne in mind that the two organizations where the

implementation was the least successful, the City

Organization and the Manufacturing Firm, employed

these systems. There was no information available

regarding the attitude of the employees in the other

two organizations using the same systems, the Food

Processing and the Construction Firm, except for the

records managers. The records managers were

admittedly experienced users, but the four systems

were not that different regarding the user interface.

On closer examination the system with the best user

acceptance, System E, may even, if anything, have

had a slightly inferior user interface. This system

was used at the Financial Institute which had the

most successful implementation (see Table 4).

4 INFORMAL ALTERNATIVES

TO RM OTHER THAN USING

ERMS

ERMS is intended to ensure systematic and uniform

classification and capture of records in any format

(paper, film and electronic) and support efficient

retrieval of records and information. The forms of

records that should be captured into ERMS are for

example: Letters, e-mail, e-mail attachments,

records in another electronic format other than

letters, e-mail and e-mail attachments, faxes, films,

photographs, drawings and maps. Using ERMS in a

correct manner prevents variable methods in record-

keeping. That diminishes possibilities of mistakes

and loss of information (Gunnlaugsdottir, 2008c).

During the interviews and the participant

observations it could be detected that employees not

using ERMS used various different methods to

classify, save, search for and retrieve records, both

records that they created themselves as well as

records received from others. They used the inbox

and outbox in the e-mail software for storing e-mail.

Some did not classify it at all, but others used some

system of their own. The employees did not usually

store attachments received separately, but kept these

with the e-mail in the e-mail software. When

employees were searching for e-mail received, they

said that they usually used the search option in the e-

mail software, and also sometimes for the outgoing

e-mail that they themselves had created. Most

employees stated that they could always find all of

the e-mail that they received or sent. Some believed

that it took too long to do so. When asked if their

fellow employees could retrieve e-mail on their

computers in their absence, if they had access, the

reply was usually negative.

Records that most employees created in-house

were saved on the shared drive of the computer

system of the organization. Some used various

department or division drives. The records did not

receive any uniform classification before storage

when these methods were used. Each employee

classified his/her records as he or she saw fit. Some

even stored their records on the hard disk in their

private computers or on floppy disks or CDs, and

classified the records according to their own private

scheme.

These employees usually used a subject name

for the classification that they felt would be used in

later retrieval. It differed how systematic the

assigning of subject names was with the employees

that were not using ERMS. Two methods, however,

were the most common: (1) The name of a party,

company, individual, or organization, or an

abbreviation that easily indicated the party in

question, and (2) the name of the type of the record,

for example, financial report, memo, agreement or a

fairly obvious abbreviation.

When employees had to search for electronic

records that they themselves had created, they

usually tried first to think of the subject name that

they had given to the record in question. With that

name in mind, they searched in their computer for

the record. Employees normally said that it was

relatively easy to retrieve records that they needed.

ELECTRONIC RECORDS MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS - The Human Factor

99

However, when asked whether their fellow

employees could find these records without their

help, the reply was usually negative.

When employees that did not use ERMS were

asked about the saving, classification and

registration of records on paper that they received

from others and kept privately, it was revealed that

these records were not stored in a uniform manner.

These records were stored in file cabinets, file

drawers or binders, not classified and not registered.

Employees were asked how well they managed to

retrieve these records. Most employees said that they

could retrieve the records when needed. Many were,

however, of the opinion that this search for records

could take too long a time. When asked if they

believed that other employees would find it easy to

retrieve these records in their absence, the reply was

usually negative.

When employees were asked about the reasons

why they did not use ERMS, they stated that the

main reason was that they had not received the

necessary education and training to use the system.

Studies of groupware and similar systems have

shown that even systems that are very good

technologically do not work, or are not being used as

intended, if they do not fit the culture of the

organization or if they are incorrectly implemented,

especially without good and proper training. When

the technology does not help the individuals to

accomplish dynamic ends and solve problems, ‘they

abandon it, or work around it, or change it, or think

about changing their ends’ (Orlikowski, 2000, pp.

423-424).

5 MONITORING BY SUPERIORS

AND THE POSSIBILITY OF

FELLOW EMPLOYEES

SEEING WORK PERFORMED

IN ERMS

It is well known that individuals are concerned about

improper and unauthorized use of personal

information about themselves. Some employees also

feel uncomfortable in allowing their co-workers

access to their records and letting them see which

projects they are working on or how they are

performing their job (Smith, Milberg and Burke,

1996; Townsend and Bennett, 2003).

The four ERMS are solutions in groupware that

makes monitoring of use possible. The great

majority, 33 of the participants, either felt positively

or were indifferent toward possibly having their

work being observed in ERMS. However, five of the

participants expressed a negative feeling as is shown

in Table 3.

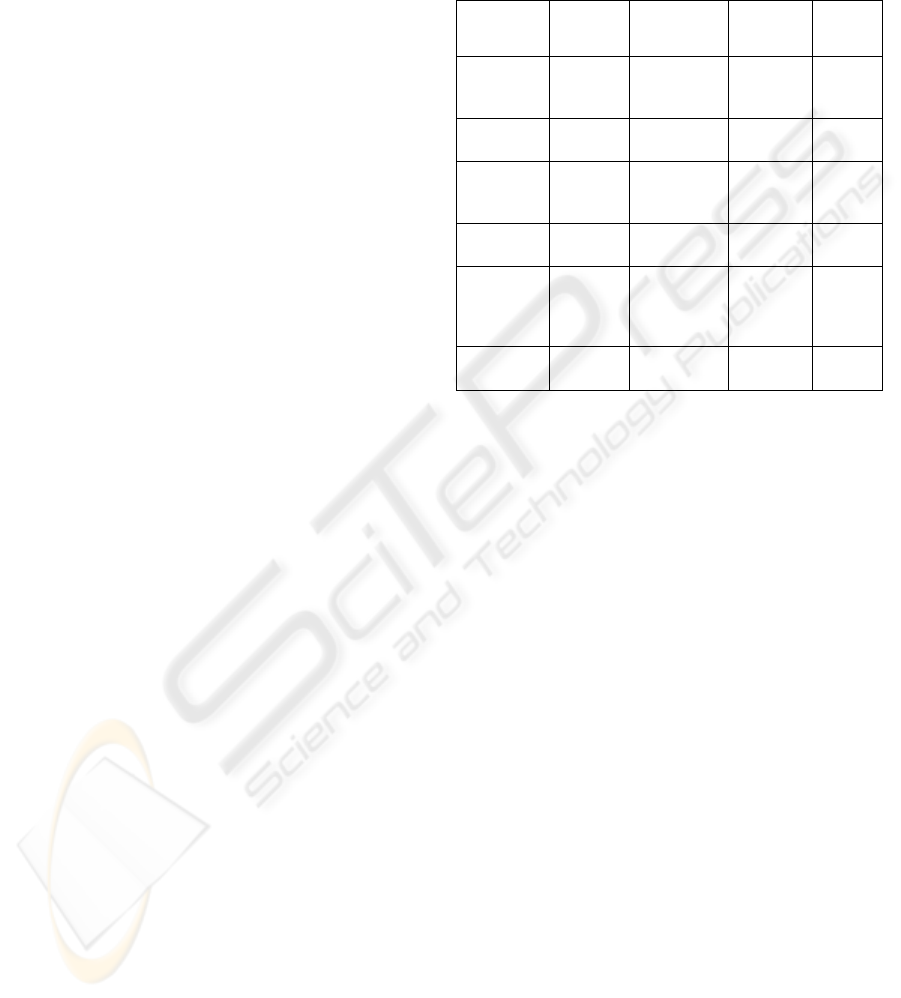

Table 3: Being monitored and observed in ERMS, feelings

according to job functions in the eight organizations.

Employees Positive Neither/Nor Negative Total

Records

managers

8 0 0 8

Managers 8 0 0 8

Computer

specialists

4 0 0 4

Specialists 4 1 3 8

General

office

employees

3 5 2 10

Total 27 6 5 38

All of the top management, the records managers

and all of the computer specialists were in

agreement that the managers should be able to

monitor the use of ERMS by the employees and they

all said that they did not worry that other employees

could see the records that they themselves created as

long as these records were not confidential.

Four of the specialists were positive about others

being able to see the records that they created, one of

them expressed no opinion, but three of them (one at

the Financial Institute and two at the City

Organization) emphasized strongly that they did not

feel comfortable knowing that their own use might

be monitored. They admitted that this was part of the

reason why they sometimes tried to avoid using

ERMS.

Five of the ten general office employees did not

express any opinion as to how they felt being

monitored or observed, and three of the general

office employees did not seem to have much

concern in this respect and were particularly

positive. Two of the ten seemed, however, to be

rather negative towards being monitored on a daily

basis. One of them said that she sometimes felt

uncomfortable saving records that she had written

into ERMS because she was afraid that the records

might contain spelling errors and bad grammar that

she did not want everyone to see.

Icelandic is a difficult language to master due to

grammar and spelling. Some employees seemed not

ICEIS 2009 - International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

100

to be at ease having their co-workers detect such

errors. Secondly some employees felt that if their

output or efficiency was being monitored, their

feelings became negative. They believed that their

superiors thought that they were not doing their job

when they were not working in ERMS. Finally,

there is the feeling of privacy. If the records deal

with sensitive or personal matters, employees

sometimes seemed to be uneasy if access to such

records was open. It is, however possible to limit

access to certain types of records or vary access by

job function, or by person. The above points could

be detected both during the interviews and the

participant observations.

Studies that have been undertaken to discover the

effects of electronic surveillance on the well-being

of employees, point to the fact that such surveillance

can cause considerable stress among employees

(Aiello and Kolb, 1995; Rafnsdottir and

Gudmundsdottir, 2004; Smith, Carayon, Sanders,

Lim and LeGrande, 1992). Monitoring of work

performed by employees in ERMS would by most

definitions not fall under electronic surveillance.

Employees, with very few exceptions, did not seem

to object that their work in ERMS was being

monitored or observed by others. They seemed to

regard this more as a management tool and a part of

the groupware function. The overview of the

processing of cases, who was processing the case

and how far had the processing progressed, has more

of the features of a management information system

than a monitoring system.

6 DISCUSSIONS

AND CONCLUSIONS

In the study it was examined how employees felt

working in ERMS. It covered the user-friendliness

of ERMS, the ways of working outside the system,

how the employees felt being possibly monitored,

and how they felt regarding sharing their work with

their fellow employees.

All of the records managers found ERMS user-

friendly. Most of their fellow employees agreed with

them. In two of the organizations, the City

Organization and the Manufacturing Firm, the

organizations with the lowest rate of expected users

using the ERMS, 25% and 15% respectively, a large

proportion of the users claimed that their system was

not user-friendly as shown in Table 4. Table 4 shows

the relationship between the implementation and the

user-friendliness of ERMS in the eight

organizations. The implementation itself is covered

in detail in a separate article (Gunnlaugsdottir,

2008a). A short summary is nevertheless in order

here.

When the number of positive implementation

factors (11 in total) was compared with the

proportion of expected users a positive relationship

was found. The greater the number of positive

implementation factors, the higher was the

proportion of expected users. There were mainly

three elements that determined the success of the

implementation: Support by top management,

participation of the records managers in the project,

and adequate and proper training.

Figure 1 shows the three elements and the 11

implementation factors.

Support by top

management

exemplified by:

Records

manager’s

participation in:

Training with

different

approaches:

Their interest in

the project

System selection

Education and

training in RM

Their own use of

ERMS

System

development

ERMS seminars

Their motivation

of employees

Adapting ERMS

to the

organization

ERMS individual

training

ERMS support

and training by IT

department

ERMS follow-up

courses

Three factors Three factors Five factors

Figure 1: The three elements and the 11 implementation

factors.

These 11 positive implementation factors explain

the success rate of the implementation as presented

in detail in Table 4.

The Financial Institute revealed 11 positive

implementation factors identified out of 11 possible.

There the proportion of expected users actually

using ERMS was 90% and everybody claimed that

the system was user-friendly. On the other hand, at

the Manufacturing Firm there was only one positive

implementation factor, the proportion of expected

users just reached 15%, and 62% of respondents

claimed that ERMS was not user-friendly.

When the employees gave up using ERMS they

worked outside it, using informal methods of their

own. The consequence of this was that their co-

workers were unable to retrieve information and

records.

Employees, with very few exceptions, did not

seem to object that their work in ERMS was being

ELECTRONIC RECORDS MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS - The Human Factor

101

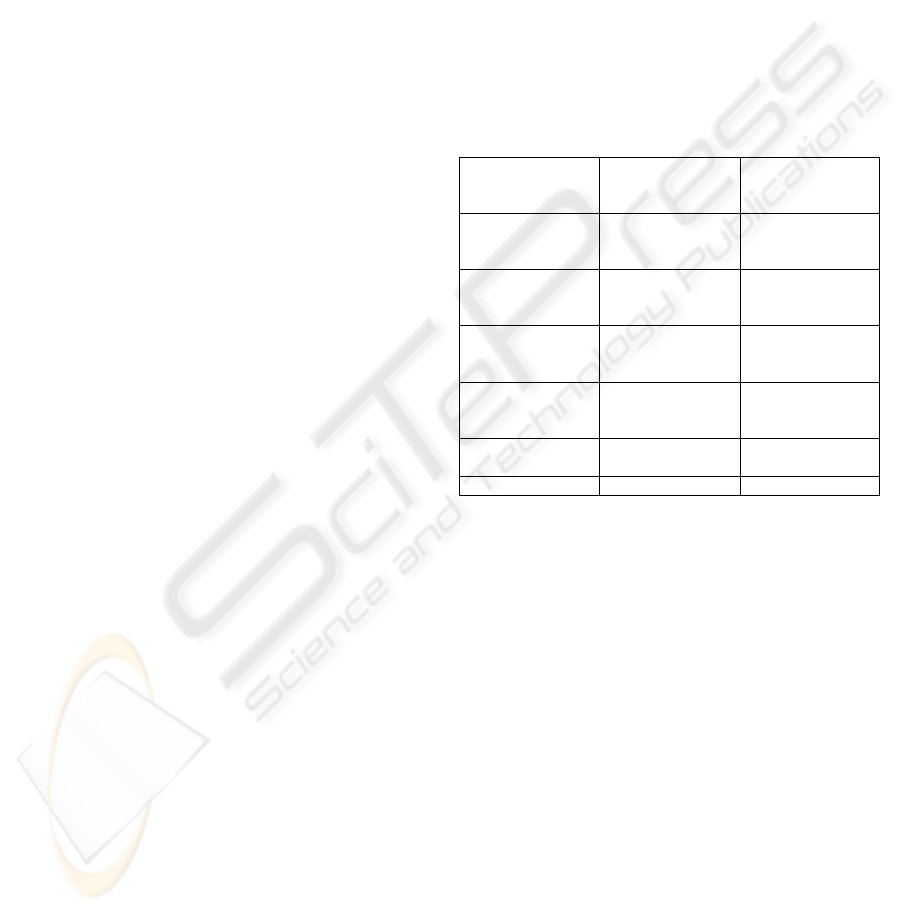

Table 4: The implementation and use of ERMS in the organizations.

Implementation

of ERMS

Government

Institution

City

Organization

Financial

Institute

Manufacturing

Firm

Public

Services

Office

Food

Processing

Municipal

Office

Constructing

Firm

Number of

positive

implementation

factors:

Support by top

management**

2 0 3 0 0 3 0 3

Records

managers

participation**

3 1 3 0 1 2 2 2

Education and

training**

3 1 5 1 3 5 4 3

Number of

positive

implementation

factors in

total**

8 2 11 1 4 10 6 8

*Estimated

proportion of

expected users

actually using

ERMS (%)**

75

(85)

25 90

15

(50)

60 80

40

(60)

70

(80)

ERMS was use-

friendly (%):

Yes 91 29 100 38

No 9 71 0 62

Notes: *The level of use was based on a careful evaluation and estimate made by the records managers. **These are the original findings.

During 2008 these results were updated as shown within brackets and discussed in this section

.

monitored or observed by others. They thought of

ERMS as a practical and successful management

tool and a part of the groupware function rather than

electronic surveillance in the negative sense of that

concept.

Follow-up interviews were conducted with the

records managers in the eight organizations in 2008.

The records managers in four of the organizations,

City Organization, Financial Institute, Public

Services Office and Food Processing believed that

they could not detect an increase in the estimated

proportion of expected users actually using ERMS.

The records managers in the other four,

Government Institution, Manufacturing Firm,

Municipal Office and Construction Firm reported

that there had been an increase. The records manager

at the Government Institution believed that the

proportion was now about 85% (was 75%). She

attributed this increase to a training project in

general RM that was undertaken during 2007. She

underlined especially the importance that employees

were now much more aware of the legal

environment that the institution was a part of than

before and that it had to meet requirements dictated

by law.

The records manager at the Manufacturing Firm

confirmed that a substantial increase had taken

place. Now, the estimated proportion of expected

users was about 50% (was 15%). The explanation

that he gave was that a considerable increase had

occurred in the use by both top and middle

management. About one third of these were now

using the system. He believed that the increase was

also due to a training effort undertaken that covered

both general training in RM and individual system

training. The records manager at the Municipal

Office said that the use had increased to about 60%

(was 40%). Increased use by managers was the main

reason. The records manager at the Construction

Firm said that the proportion had now reached about

80% (was 70%). This good result was due to

training courses that were held and covered general

training in RM where the users did learn that

organized and proper use of ERMS resulted in more

efficiency for the firm. The employees could now

find information quicker and with greater certainty.

The follow-up interviews brought also out

another interesting fact. The training that was

undertaken subsequent to the original study seemed

to make the claims disappear that the system was

lacking in user-friendliness. This point was

especially underlined at the Manufacturing Firm

where the level of use had increased from 15% to

50%.

ICEIS 2009 - International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

102

It is of interest to investigate further the

importance of training for the implementation and

use of ERMS. A larger sample, properly

constructed, could reveal the statistical significance

of the relationship. However, there is a strong

central tendency of social forms. Hence, a large

sample is not needed to detect the importance of

training for effective implementation and use of

ERMS.

During the initial study, there was some reason

to believe that some employees may have been

blaming the system for their inability to use ERMS

when in fact the reason was lack of training. This

suspicion detected during the participant observation

was confirmed in the follow-up during 2008. If the

employees lacked in their ability to use the system,

the fault lay with the system, not themselves, and

their lack of training. Improved training

subsequently turned disbelievers into active users.

REFERENCES

Aiello, J. R. and Kolb, K.J. (1995), “Electronic

performance monitoring and social context: impact on

productivity and stress”, Journal of Applied

Psychology, Vol. 80, pp. 339-353.

ARMA International (2004), Framework for Integration

of Electronic Document Management Systems and

Electronic Records Management Systems

(ANSI/AIIM/ARMA TR48-2004): Technical Report,

ARMA International, Lenexa, KS.

Bogdan, R.C. and Biklen, S.K. (2003), Qualitative

Research for Education: An Introduction to Theory

and Methods (4

th

ed.), Allyn and Bacon, Boston, MA.

CECA (CECA-CEE-CEE) (2001), MoReq: Model

Requirements for the Management of Electronic

Records: MoReq Specification, CECA-CEE-CEEA,

Bruxelles, Luxembourg.

CECA (CECA-CEE-CEE) (2008), MoReq2: Model

Requirements for the Management of Electronic

Records: Update and Extension, 2008: MoReq2

Specification, CECA-CEE-CEEA, Bruxelles,

Luxembourg.

Coleman, D. (1999), “Groupware: collaboration and

knowledge sharing”, in Liebowitz, J. (Ed.), Knowledge

Management Handbook, CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL,

pp. 12-1 – 12-15.

Denzin, N. K. and Lincoln, Y. S. (2003), “Introduction:

the discipline and practice of qualitative research”, in

Denzin, N.K. and Lincoln, Y.S. (Eds.), Strategies of

Qualitative Inquiry, Sage Publications, Thousand

Oaks, CA, pp. 1-19.

DoD (Department of Defense, US) (2002), Design

Criteria Standard for Electronic Records Management

Software Applications: DoD 5015.2-STD, Assistant

Secretary of Defense for Command, Control,

Communication and Intelligence, Washington, DC.

DoD (Department of Defense, US) (2007), Electronic

Records Management Software Applications Design

Criteria Standard: DoD 5015.02-STD, Assistant

Secretary of Defense for Networks and Information

Integration, Department of Defense Chief Information

Officer, Washington, DC, available at: http://

jitc.fhu.disa.mil/recmgt/p50152s2.pdf (accessed 1

November 2008).

Gorman, G.E. and Clayton, P. (1997), Qualitative

Research for the Information Professional: A

Practical Handbook, Library Association Publishing,

London.

Gunnlaugsdottir, J. (2008a), “As you sow, so you will

reap: implementing ERMS”, Records Management

Journal, Vol. 18 No. 1, pp. 21-39.

Gunnlaugsdottir, J. (2004), “Organising information into

groupware: is the implementation of such systems of

value to universities?”, in Arkiv med ambitioner:

framtidsperspektiv och kvalitativ utveckling på

kulturens grund: föredrag från NUAS Arkivkonferens i

Reykjavik 7 och 8 oktober 2004, Haskoli Islands,

skjalasafn [University of Iceland, the Archives],

Reykjavik, pp. 7-22.

Gunnlaugsdottir, J. (2008b), “Registering and searching

for records in electronic records management

systems”, International Journal of Information

Management, Vol. 28, pp. 293-304.

Gunnlaugsdottir, J. (2003), “Seek and you will find, share

and you will benefit: organising knowledge using

groupware systems”, International Journal of

Information Management, Vol. 23, pp. 363-380.

Gunnlaugsdottir, J. (2008c), “Thykja rafraen

skjalastjornarkerfi notendavaen? [Do employees find

electronic records management systems user-

friendly?]”, in Johannesson, Th.J. and Bjornsdottir, H.

(Eds.), Rannsoknir i felagsvisindum IX:

felagsvisindadeild: erindi flutt a radstefnu i oktober

2008 [Research in social sciences IX: proceedings

from a conference, October 2008],

Felagsvisindastofnun [Social Science Research

Institute], Reykjavik, pp. 79-90.

ISO (2001a), ISO 15489-1:2001: Information and

Documentation – Records Management: Part 1:

General, International Organization for

Standardization, Geneva.

ISO (2001b), ISO/TR 15489-2:2001: Information and

Documentation – Records Management: Part 2:

Guidelines, International Organization for

Standardization, Geneva.

King, N. (1999), “The qualitative research interview, in

Cassell, C. and Symon, G. (Eds.), Qualitative methods

in organizational research: a practical guide, Sage

Publications, London, pp. 14-36.

Kvale, S. (1996), Interviews: An Introduction to

Qualitative Research Interviewing, Sage Publications,

Thousand Oaks, CA.

Orlikowski, W. J. (2000), “Using technology and

Constituting structures: A Practice lens for Studying

Technology in Organizations”, Organization Science,

ELECTRONIC RECORDS MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS - The Human Factor

103

Vol. 11 No. 4, pp. 404-428

Orlikowski, W.J. and Barley, S.R. (2001), “Technology

and institutions: what can research on information

technology and research on organizations learn from

each other?”, MIS Quarterly, Vol. 25 No. 2, pp. 145-

165.

Rafnsdottir, G. and Gudmundsdottir, L. (2004),

“Upplysingataekni: eftirlitsthjodfelag [Information

technology: the monitoring society]”, in Hauksson, U.

(Ed.), Rannsoknir i felagsvisindum V:

felagsvisindadeild: erindi flutt a radstefnu i oktober

2004 [Research in social sciences V: proceedings

from a conference, October 2004], Haskolautgafan

[University of Iceland, University Press], Reykjavik,

pp. 181-191.

Silverman D. (2005), Doing Qualitative Research: A

Practical Handbook (4

th

ed.), Sage Publication,

London.

Smith, H.J., Milberg, S.J. and Burke, S.J. (1996),

“Information privacy: measuring Individuals’ concerns

about organizational practices”, MIS Quarterly, Vol.

20 No. 2, pp. 167-191.

Smith, M.J., Carayon, P., Sanders, K.J, Lim, S-Y. and

LeGrande, D. (1992), “Employee stress and health

complaints in jobs with and without electronic

performance monitoring, Applied Ergonomics, Vol.

22, pp. 17-27.

Statistics Iceland (2006), Notkun fyrirtaekja a

upplysingataeknibunadi og rafraenum vidskiptum

2006 [ICT and E-commerce in Enterprises 2006],

Hagstofa Islands [Statistics Iceland], Reykjavik.

Statistics Iceland (2007), Use of Computers and the

Internet by Households and Individuals 2007,

Hagstofa Islands [Statistics Iceland], Reykjavik.

Townsend, A.M. and Bennett, J.T. (2003), “Privacy,

technology, and conflict: emerging issues and action in

workplace privacy”, Journal of Labor Research, Vol.

15 No. 3, pp. 195-205.

ICEIS 2009 - International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

104